Whereas most peripheral CD8+ αβ T cells highly express CD8αβ heterodimer in healthy individuals, there is an increase of CD8α+βlow or CD8αα αβ T cells in HIV infection or Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and after bone marrow transplantation. The significance of these uncommon cell populations is not well understood. There has been some question as to whether these subsets and CD8α+βhigh cells belong to different ontogenic lineages or whether a fraction of CD8α+βhigh cells have down-regulated CD8β chain. Here we assessed clonality of CD8αα and CD8α+βlow αβ T cells as well as their phenotypic and functional characteristics. Deduced from surface antigens, cytotoxic granule constituents, and cytokine production, CD8α+βlow cells are exclusively composed of effector memory cells. CD8αα cells comprise effector memory cells and terminally differentiated CD45RO−CCR7−memory cells. T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) spectratyping analysis and subsequent sequencing of CDR3 cDNA clones revealed polyclonality of CD8α+βhigh cells and oligoclonality of CD8α+βlow and CD8αα cells. Importantly, some expanded clones within CD8αα cells were also identified within CD8α+βhigh and CD8α+βlow subpopulations. Furthermore, signal-joint TCR rearrangement excision circles concentration was reduced with the loss of CD8β expression. These results indicated that some specific CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells expand clonally, differentiate, and simultaneously down-regulate CD8β chain possibly by an antigen-driven mechanism. Provided that antigenic stimulation directly influences the emergence of CD8αα αβ T cells, these cells, which have been previously regarded as of extrathymic origin, may present new insights into the mechanisms of autoimmune diseases and immunodeficiencies, and also serve as a useful biomarker to evaluate the disease activities.

Introduction

CD8 is a coreceptor that recognizes the nonpolymorphic α3 domain of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules and is necessary for T-cell activation.1,2 It increases the avidity of the interaction between the CD8-bearing T cell and the antigen-presenting cell.1,3,4 With the T-cell receptor (TCR)–peptide-MHC ligation, simultaneous coligation of the coreceptor juxtaposes MHC-engaged TCR complexes with intracellular signaling intermediates, leading to increased tyrosine phosphorylation and further recruitment and activation of downstream signaling effector molecules.2,5-7 CD8 antigen is composed of 2 kinds of molecules, α and β chain, and is expressed either as an αα homodimer or an αβ heterodimer.8-11 These isoforms are the products of closely linked but distinct genes exhibiting only moderate sequence homology.12,13 Studies of CD8α and CD8β have revealed the distinct contributions to the coreceptor function. CD8α can interact with all molecules presently known to be involved in CD8 function by itself. CD8β, on the contrary, has roles to make the coreceptor function more efficiently as CD8αβ heterodimers. Extracellular domain of CD8β increases the avidity of CD8 binding to MHC class I14 and influences specificity of the CD8/MHC/TCR interaction.15 CD8β may also uniquely mediate efficient interaction with the TCR/CD3 complex.16In addition, the intracellular domain of CD8β enhances association of CD8α with Lck and linker for activation of T cells (LAT).14,17 18

In healthy individuals, most thymocytes and peripheral T cells highly express the heterodimeric form of CD8.17 These CD8α+βhigh T cells express not only CD8αβ heterodimers but also CD8αα homodimers on the same cells.9,10 On the other hand, specific subpopulations of natural killer (NK) cells and intestinal γδ T cells exclusively express CD8αα.17 However, CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells increase in the periphery in some conditions. Patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) are reported to have CD8+ T cells composed mostly of CD8αα homodimers.19 Also, a large proportion of CD8+ T cells reconstituted in bone marrow transplant recipients express CD8αα homodimers.20,21 In addition, HIV infection is characterized by the appearance of a major CD8 subpopulation with reduced CD8β chains, which exhibits strong antiviral activity.22

Although there has been much controversy as to the origin and the functional roles of these cells, there is increasing evidence in recent literature to suggest that CD8αα αβ T cells derive from the thymus after positive selection and that they exhibit distinct functions from conventional CD8αβ αβ T cells.23,24Furthermore, it seems that expression of CD8α chains is secondarily regulated by the intestinal microenvironments.25 However, despite the extensive studies of CD8α and β chains in vitro and the studies on a molecular basis, heterogeneity of CD8 isoform expression may not have been examined thoroughly in various human disorders and clinical conditions. Moreover, the in vivo function and clinical significance of CD8αα and CD8α+βlowαβ T cells are poorly understood. The purpose of this study is to reveal in vivo cell function and the origin of CD8αα and CD8α+βlow αβ T cells. More specifically, we analyzed cell surface antigen expression, cytotoxic granule constituents, and cytokine production of these subpopulations. Furthermore, this study also examined if CD8αα and CD8α+βlow αβ T cells comprise distinct clones, or if they descend directly from CD8α+βhigh cells by down-regulating CD8β chain after antigen stimulation in vivo.

Materials and methods

Monoclonal antibodies

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) recognizing CD95, CD45RO, and R-phycoerythrin-Cyanine5 (RPE-Cy5)–conjugated anti-CD8α mAb were purchased from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark). FITC-conjugated mAbs against CD16, CD27, CD57, TCRαβ, interleukin 2 (IL-2), interferon γ (IFN-γ), and mouse IgG antibodies as well as nonconjugated anti-CCR7 mAbs were obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). FITC-conjugated anti-CD28, anti-TCRγδ, anti-CD62L, PE-conjugated anti-CD8β, anti-2B4, anti–TIA-1 (a cytotoxic granule-associated protein), and nonconjugated anti-CD8β mAbs were products of Beckman Coulter (Tokyo, Japan). PE-conjugated mAbs against perforin and granzyme B were purchased from Ancell (Bayport, MN) and Research Diagnostics (Flanders, NJ), respectively.

Cell preparation and flow cytometric analysis

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) were isolated from heparinized peripheral blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation. CD16+ and TCRγδ+ cells were then depleted using MACS and anti-FITC magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) after staining with FITC-conjugated anti-TCRγδ and anti-CD16 mAbs. The negatively sorted cells (purity > 99%) were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD8β and RPE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD8α mAb in combination with FITC-conjugated anti-TCRαβ, anti-CD62L, anti-CD57, anti-CD95, anti–HLA-DR, or anti-CD45RO mAbs. For the analysis of CCR7 expression, nonconjugated anti-CCR7 mAbs were used with FITC-conjugated goat antimouse antibodies. Similarly, 2B4 expression was analyzed using FITC-conjugated goat antimouse antibodies with the staining with nonconjugated anti-CD8β mAbs and PE-conjugated anti-2B4 mAbs. These stained cells, after washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan). In addition, for signal-joint TCR rearrangement excision circles (Sj TRECs) quantification and TCR complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) spectratyping and sequencing, CD8α+αβ T cells with different (high, low, or negative) CD8β expression were separated using an Epics ELITE flow cytometer (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL) after depletion of CD4+, CD14+, CD16+, CD20+, and TCRγδ+ cells with MACS (purity > 98%). Patterns of flow cytometric analysis pursued for 3 to 6 independent donors were similarly otherwise noted, and the representative results were presented.

Flow cytometric detection of cytokine production and intracellular staining for cytotoxic granule constituents

TCRγδ-depleted and CD16-depleted PBMNCs (TCRγδ− CD16− PBMNCs) were stimulated for 6 hours with 10 ng/mL phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and 500 ng/mL A23187 in the presence of 1 μg/mL monensin (Sigma, St Louis, MO). After cell surface staining with PE-conjugated CD8β and RPE-Cy5–conjugated CD8α, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus Kit (BD Pharmingen) per the manufacturer's instruction. Staining of the cytoplasm with FITC-conjugated anti–IFN-γ or anti–IL-2 mAb followed. Separately, freshly isolated TCRγδ−CD16− PBMNCs were treated with anti-CD8β mAb followed by FITC-conjugated goat antimouse antibodies. They were further stained with RPE-Cy-5–conjugated anti-CD8α mAbs after blocking with normal mouse serum. After fixation and permeabilization, the cells were stained with PE-conjugated antiperforin, antigranzyme B, or anti–TIA-1 mAbs.

RNA extraction and cDNA preparation

Total RNA was extracted from separated CD8+ αβ T cells with TRIZOL reagent following the manufacturer's instructions (Gibco BRL, Bethesda, MD). The RNA was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA in a reaction primed with oligo(dt)12-18 using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase as recommended by the manufacturer (Gibco BRL).

Sj TREC quantification

Sj TRECs were quantified in sorted CD8+ αβ T-cell subsets by a real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method as described previously.26 27 Sorted cells were lysed in 100 μg/mL proteinase K (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) for 1 hour at 56°C and then 10 minutes at 95°C at 107 cells/mL. Then PCR was carried out on 5 μL cell lysate in a spectrofluorometric thermal cycler (ABI PRISM 7700, Applied Biosystems, Osaka, Japan) under the following conditions: 50°C for 2 minutes followed by 95°C for 10 minutes, after which 50 cycles of amplification were carried out (95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute). The sequences of the primers and probe used were the following: forward primer GGAAAACACAGTGTGACATGGA, reverse primer GTCAACAAAGGTGATGCCACAT, and the probe FAM-CCTGTCTGCTCTTCATTCACCGTTCTCA-TAMRA. A standard curve was plotted, and Sj TREC values for samples were calculated by ABI PRISM 7700 software.

CDR3 spectratyping

CDR3 spectratyping was pursued as previously described.28 Briefly, cDNA was amplified by PCR through 35 cycles (94°C for 1 minute, 55°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute) with a primer specific to 24 different BV subfamilies (BVs 1-2029 and BVs21-2430) and a fluorescent BC primer.29 The fluorescent PCR products were mixed with formamide and the size standard (GeneScan-500 TAMRA, Applied Biosystems). After denaturation for 2 minutes at 90°C, the products were analyzed with an automated 310 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems), and the data were analyzed with GeneScan software (Applied Biosystems).

The overall complexity within a Vβ subfamily was determined by counting the numbers of discrete peaks and determining their relative size on the spectratype histogram. We used a complexity scoring system31 with our interpretation, that is, complexity score = (sum of all the peak heights/sum of the major peak heights) × (number of the major peaks). Major peaks were defined as those peaks on the spectratype histogram whose amplitude was at least 10% of the sum of all the peak heights.

Cloning and sequencing of PCR-amplified cDNA

The PCR products of some BV cDNA were electrophoresed on an agarose gel and purified using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan), and then cloned with TOPO TA Cloning (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Eleven to 19 colonies containing the insert fragment were randomly selected. Purified with QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen), the recombinant plasmids were subjected to fluorescence dye terminator cycle sequencing, and the sequence reactions were analyzed on a 310 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) after removal of the unincorporated fluorescence dye with Centri-Sep Spin Columns (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

Association of the percentage of peripheral CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells with age was analyzed using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was applied to examine statistically significant differences of CDR3 complexity scores between subpopulations of different CD8β expression.

Results

CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells expand with advancing age

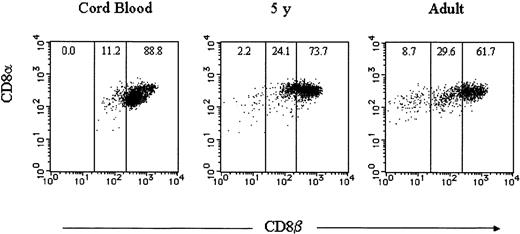

To ensure that the number of peripheral CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells are limited in healthy individuals, we first stained PBMNCs with anti-TCRαβ, anti-CD8β, and anti-CD8α mAbs conjugated to different fluorochromes in several healthy individuals including cord blood. CD8α+ TCRαβ+ cells could be classified into 3 groups defined by the level of CD8β expression: CD8α+βhigh, CD8 α+βlow, and CD8 α+β−, which is CD8αα. Although CD8αα αβ T cells were negligible and small numbers of CD8α+βlow αβ T cells existed in cord blood, these populations increased in a 5-year-old child and even more in an adult (Figure 1). To assess the developmental changes of CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells, we evaluated the frequency of these subpopulations in various age groups using more blood samples. In cord blood, CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells represented a minor population within CD8α+αβ T cells. These subpopulations increased with advancing age as expected (P < .01). However, it is notable that some adults showed levels of CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells as low as neonates (Figure2).

CD8β expression on CD8α+ αβ T cells in healthy individuals.

PBMNCs from healthy individuals and cord blood were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-TCRαβ, PE-conjugated anti-CD8β, and RPE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD8α mAbs. TCRαβ and CD8α gated cells were analyzed for the expression of CD8α (y-axis) versus CD8β (x-axis). Representative data are displayed.

CD8β expression on CD8α+ αβ T cells in healthy individuals.

PBMNCs from healthy individuals and cord blood were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-TCRαβ, PE-conjugated anti-CD8β, and RPE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD8α mAbs. TCRαβ and CD8α gated cells were analyzed for the expression of CD8α (y-axis) versus CD8β (x-axis). Representative data are displayed.

Developmental change of CD8α+βlow and CD8αα fractions within CD8α+ αβ T cells.

CD8α+ αβ T cells were analyzed for CD8β expression, and the total frequencies of CD8α+βlow and CD8αα fractions were plotted along different age groups.

Developmental change of CD8α+βlow and CD8αα fractions within CD8α+ αβ T cells.

CD8α+ αβ T cells were analyzed for CD8β expression, and the total frequencies of CD8α+βlow and CD8αα fractions were plotted along different age groups.

Correlation of CD8β expression with other surface markers

We next compared the expression of the various surface antigen markers on CD8α+ αβ T cells with different levels of CD8β expression. Before pursuing 3-color flow cytometric analysis, we depleted CD16+ NK cells and TCRγδ+ T cells from PBMNCs because these cells contain CD8α+ cells. The depletion of CD16+ and TCRγδ+ cells yielded TCRαβ+ or CD3+ cells with more than 98% purity when gated on CD8α (Figure 3A). CD8α+βhigh cells were heterogeneous for the expression of all the surface antigens analyzed. In the CD8α+βlow subpopulation, CD95+, CD45RO+, and 2B4+ cells became dominant, and the subset lost CD62L and CCR7 antigens. Most CD8αα T cells expressed CD95 and 2B4, but not CD57, CD62L, or CCR7. Although more than half of 7 adults analyzed had CD8αα cells, which exclusively expressed CD45RO, CD27, and CD28, the rest of the individuals possessed CD8αα cells that were as much as 30% negative for these surface antigens (Figure 3B and data not shown).

Analysis of surface antigen expression on CD8α+ αβ T cells.

TCRγδ− CD16− PBMNCs were stained with CD8β, CD8α, and TCRαβ or CD3 (A), or other various surface antigens as indicated (B). CD8α gated cells are displayed.

Analysis of surface antigen expression on CD8α+ αβ T cells.

TCRγδ− CD16− PBMNCs were stained with CD8β, CD8α, and TCRαβ or CD3 (A), or other various surface antigens as indicated (B). CD8α gated cells are displayed.

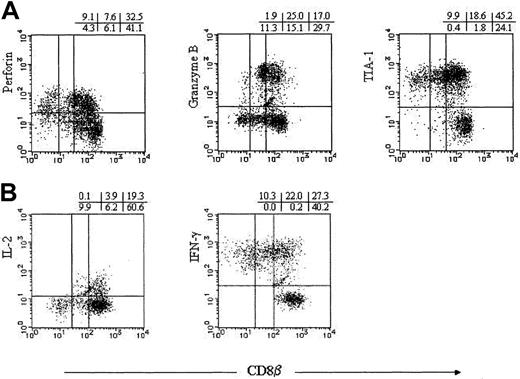

Cytotoxic granule proteins and cytokine production

To further characterize the subpopulations of CD8+αβ T cells with regard to CD8β-chain expression, we analyzed CD8+ αβ T cells for the presence of perforin, granzyme B, and TIA-1. CD8α+βhigh cells were heterogeneous for the expression of the cytotoxic granule constituents. CD8α+βlow cells were also heterogeneous for the expression of perforin and granzyme B, but the subset entirely expressed TIA-1. A large number of CD8αα T cells possessed perforin and nearly all the cells contained TIA-1, whereas CD8αα cells did not contain granzyme B (Figure 4A).

Cytotoxic granule constituents and cytokine production.

(A) TCRγδ− CD16− PBMNCs were stained with anti-CD8β mAbs recognized by FITC-conjugated goat-antimouse antibodies, RPE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD8α, and PE-conjugated antiperforin, antigranzyme B, or anti–TIA-1 mAbs. (B) After the stimulation with PMA and A23187 in the presence of monensin, TCRγδ−CD16− PBMNCs were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD8β, RPE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD8α, and FITC-conjugated anti–IL-2 or anti–IFN-γ mAbs. CD8α gated cells are displayed.

Cytotoxic granule constituents and cytokine production.

(A) TCRγδ− CD16− PBMNCs were stained with anti-CD8β mAbs recognized by FITC-conjugated goat-antimouse antibodies, RPE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD8α, and PE-conjugated antiperforin, antigranzyme B, or anti–TIA-1 mAbs. (B) After the stimulation with PMA and A23187 in the presence of monensin, TCRγδ−CD16− PBMNCs were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD8β, RPE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD8α, and FITC-conjugated anti–IL-2 or anti–IFN-γ mAbs. CD8α gated cells are displayed.

Because cytokine production capacity is also a major factor determining cell functions, CD8+ αβ T cells were stimulated for 6 hours with PMA and calcium ionophore in the presence of monensin for analysis of IFN-γ and IL-2 production. Heterogeneity for the cytokine production was observed in the CD8α+βhighsubset. Entire CD8α+βlow cells produced IFN-γ, and some proportion of the cells produced IL-2. CD8αα cells exclusively expressed IFN-γ, but not IL-2 (Figure 4B).

CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells exhibit less clonal diversity

Sequence analysis of CDR3 length diversity in CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells was pursued to define the extent of clonal expansion. About 5 × 105 cells of each subpopulation were isolated, and their cDNA was subjected to PCR amplification with 24 Vβ-specific primers. TCR spectratypes of CD8α+βhighcells exhibited, with a few exceptions, a gaussianlike distribution, indicating that the subset comprises cells with highly diverse and polyclonal TCR repertoires. The profile of CD8α+βlow cells revealed skewed CDR3 size distribution in some Vβ subfamilies, but about one third of Vβ subfamilies remained diverse. To a further extent, the majority of Vβ subfamilies of CD8αα cells displayed apparently skewed patterns, many of them with an almost single peak pattern (Figure5).

Spectratypes of the T-cell repertoire within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells.

Histograms of the relative sizes of the PCR-amplified CDR3 region within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells in one donor are shown. The y-axis is relative quantity of RNA bearing the specific TCR Vβ. The x-axis represents the nucleotide length of the PCR-amplified TCR gene products.

Spectratypes of the T-cell repertoire within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells.

Histograms of the relative sizes of the PCR-amplified CDR3 region within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells in one donor are shown. The y-axis is relative quantity of RNA bearing the specific TCR Vβ. The x-axis represents the nucleotide length of the PCR-amplified TCR gene products.

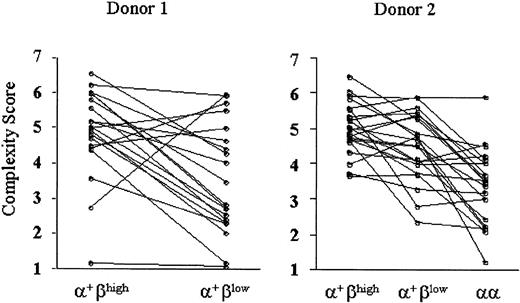

To quantify differences in the TCR Vβ gene repertoire among the T-cell subsets, we assigned complexity scores to each sample analyzed. Samples from 2 donors were presented; one of them (donor 1) did not possess CD8αα αβ T cells enough to be isolated. In donor 1, complexity scores of CD8α+βlowcells were significantly lower than CD8α+βhigh cells (P < .01). Likewise, complexity scores of CD8α+ αβ T cells in donor 2 decreased as they lost CD8β expression (CD8α+βhigh versus CD8α+βlow cells, P < .05; CD8α+βlow versus CD8αα cells,P < .001; Figure 6). These results suggest that CD8α+βlow and, to a larger extent, CD8αα αβ T cells comprise oligoclonally proliferated cells.

Comparison of TCR Vβ CDR3 complexity scores among CD8α+ αβ T cells with different CD8β expression.

Complexity scores were generated for each TCR BV from the CDR3 spectratype analysis. The individual complexity scores were plotted along CD8β expression, and the dots for the same BVs were connected with lines. Representative data of 2 donors are shown.

Comparison of TCR Vβ CDR3 complexity scores among CD8α+ αβ T cells with different CD8β expression.

Complexity scores were generated for each TCR BV from the CDR3 spectratype analysis. The individual complexity scores were plotted along CD8β expression, and the dots for the same BVs were connected with lines. Representative data of 2 donors are shown.

Identical clones exist among CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα cells

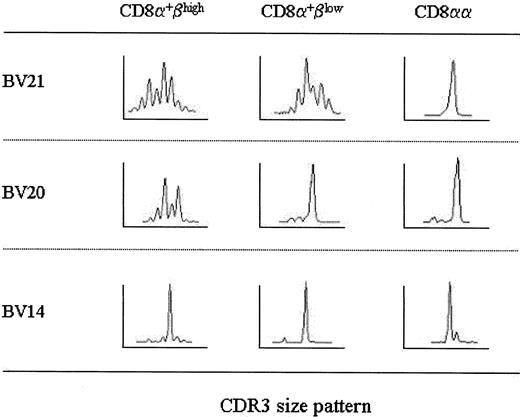

It needs to be confirmed directly that CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells are oligoclonally proliferated cells. Therefore, the PCR products were then cloned and the nucleotide sequence of CDR3 was determined (Table1). This analysis also provides the information if identical clones exist among the subpopulations of different CD8β expression. In this experiment, we used the cDNA samples from one donor so that the pruity of each sorted cell fraction was more than 98% and the number was identical for all BVs within a given cell fraction. In addition, we selected BV21, BV20, and BV14 because these BVs exhibited distinct patterns of spectratypes within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells (BV21: polyclonal, polyclonal, and oligoclonal; BV20: polyclonal, oligoclonal, and oligoclonal; and BV14: oligoclonal, oligoclonal, and oligoclonal; Figure 7).

The amino acid composition of the CDR3 region within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells

| CD8+high . | CD8α+βlow . | CD8αα . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV . | N-D-N . | BJ . | Frequency . | BV . | N-D-N . | BJ . | Frequency . | BV . | N-D-N . | BJ . | Frequency . |

| BV21 | |||||||||||

| CASS | SGTAV | SNQP (1S6) | 2/19 | CASS | PVSGRL | VNEQ (2S1) | 3/16 | CASS | PVSGRL | VNEQ (2S1) | 9/16 |

| CASS | LDPSQGH | TQVF (2S3) | 2/19 | CASS | LDPSQGH | TQVF (2S3) | 3/16 | CASS | TTLAGT | VNEQ (2S1) | 1/16 |

| CASS | FVSGS | STDT (2S3) | 1/19 | CASS | FVSGS | STDT (2S3) | 3/16 | CASS | FVSGS | STDT (2S3) | 2/16 |

| CASS | TMG | ETQV (2S5) | 2/19 | CASS | PMR | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/16 | CASS | LEGRV | QETQ (2S5) | 1/16 |

| CASS | TPRTGS | SGAN (2S6) | 2/19 | CASS | PLSC | EQFF (2S1) | 1/16 | CASS | LVQGPP | DTQV (2S3) | 1/16 |

| CASS | PSL | NTEA (1S1) | 1/19 | CASS | SPGGA | TQVF (2S3) | 1/16 | CASS | LGGGSF | VEQV (2S7) | 1/16 |

| CASS | LGP | NTEA (1S1) | 1/19 | CASS | FVSVS | STDT (2S3) | 1/16 | CAS | RGLAA | QETQ (2S5) | 1/16 |

| CASS | SGTGALL | EQFF (2S1) | 1/19 | CASS | LGGGLSP | KNIQ (2S4) | 1/16 | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | FPMGDRASGGD | TGEL (2S2) | 1/19 | CASS | SVCGRLS | NEQF (2S1) | 1/16 | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | INPSQGH | TQVF (2S3) | 1/19 | CASS | FVSGRLSNA | QVFG (2S3) | 1/16 | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | LAGGP | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | PSGTE | ETQV (2S5) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | LARD | VEQV (2S7) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | LGP | SVEQ (2S7) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | FGIGDS | SVEQ (2S7) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| BV20 | |||||||||||

| CAW | SPVSWA | GNTI (1S3) | 2/15 | CAW | SPVSWA | GNTI (1S3) | 9/11 | CAW | SPVSWA | GNTI (1S3) | 10/14 |

| CA | CRGCGR | STDT (2S3) | 1/15 | CAWS | GI | VNEQ (2S1) | 2/11 | CAWS | GI | VNEQ (2S1) | 1/14 |

| CA | QALI | STDT (2S3) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | CAW | GLAD | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/14 |

| CAW | SAGTGG | VEQV (2S7) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | CAW | SIGTSGM | VEQV (2S1) | 1/14 |

| CAW | SPSDGGRSLH | NEQF (2S1) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | CAWS | FLSETGLI | GELF (2S2) | 1/14 |

| CAW | SDAGVH | EQVF (2S7) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAW | IRTSGAN | NEQF (2S1) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAW | MR | DTQV (2S3) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | QGAGE | EQFF (2S1) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | VLS | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | VMAR | VEQV (2S7) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | VEGV | NEKL (1S4) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | VTGGQ | DTQV (2S3) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | DPGD | EQVF (2S7) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| BV14 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| ASSL | GQSR | ETQV (2S5) | 7/11 | ASSL | GQSR | ETQV (2S5) | 10/11 | ASSL | GQSR | ETQV (2S5) | 6/13 |

| ASS | RGQG | VEQV (2S7) | 1/11 | ASSL | FPTGR | EKLF (1S4) | 1/11 | ASSL | FPTGR | EKLF (1S4) | 4/13 |

| ASS | SVGGRS | EQFF (2S1) | 1/11 | — | — | — | — | ASSL | EGQT | SPLH (1S6) | 2/13 |

| ASS | IAGIRTLD | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/11 | — | — | — | — | ASS | FELAGGA | ETQV (2S5) | 1/13 |

| ASS | SSGGS | SVNE (2S1) | 1/11 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CD8+high . | CD8α+βlow . | CD8αα . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV . | N-D-N . | BJ . | Frequency . | BV . | N-D-N . | BJ . | Frequency . | BV . | N-D-N . | BJ . | Frequency . |

| BV21 | |||||||||||

| CASS | SGTAV | SNQP (1S6) | 2/19 | CASS | PVSGRL | VNEQ (2S1) | 3/16 | CASS | PVSGRL | VNEQ (2S1) | 9/16 |

| CASS | LDPSQGH | TQVF (2S3) | 2/19 | CASS | LDPSQGH | TQVF (2S3) | 3/16 | CASS | TTLAGT | VNEQ (2S1) | 1/16 |

| CASS | FVSGS | STDT (2S3) | 1/19 | CASS | FVSGS | STDT (2S3) | 3/16 | CASS | FVSGS | STDT (2S3) | 2/16 |

| CASS | TMG | ETQV (2S5) | 2/19 | CASS | PMR | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/16 | CASS | LEGRV | QETQ (2S5) | 1/16 |

| CASS | TPRTGS | SGAN (2S6) | 2/19 | CASS | PLSC | EQFF (2S1) | 1/16 | CASS | LVQGPP | DTQV (2S3) | 1/16 |

| CASS | PSL | NTEA (1S1) | 1/19 | CASS | SPGGA | TQVF (2S3) | 1/16 | CASS | LGGGSF | VEQV (2S7) | 1/16 |

| CASS | LGP | NTEA (1S1) | 1/19 | CASS | FVSVS | STDT (2S3) | 1/16 | CAS | RGLAA | QETQ (2S5) | 1/16 |

| CASS | SGTGALL | EQFF (2S1) | 1/19 | CASS | LGGGLSP | KNIQ (2S4) | 1/16 | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | FPMGDRASGGD | TGEL (2S2) | 1/19 | CASS | SVCGRLS | NEQF (2S1) | 1/16 | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | INPSQGH | TQVF (2S3) | 1/19 | CASS | FVSGRLSNA | QVFG (2S3) | 1/16 | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | LAGGP | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | PSGTE | ETQV (2S5) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | LARD | VEQV (2S7) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | LGP | SVEQ (2S7) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CASS | FGIGDS | SVEQ (2S7) | 1/19 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| BV20 | |||||||||||

| CAW | SPVSWA | GNTI (1S3) | 2/15 | CAW | SPVSWA | GNTI (1S3) | 9/11 | CAW | SPVSWA | GNTI (1S3) | 10/14 |

| CA | CRGCGR | STDT (2S3) | 1/15 | CAWS | GI | VNEQ (2S1) | 2/11 | CAWS | GI | VNEQ (2S1) | 1/14 |

| CA | QALI | STDT (2S3) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | CAW | GLAD | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/14 |

| CAW | SAGTGG | VEQV (2S7) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | CAW | SIGTSGM | VEQV (2S1) | 1/14 |

| CAW | SPSDGGRSLH | NEQF (2S1) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | CAWS | FLSETGLI | GELF (2S2) | 1/14 |

| CAW | SDAGVH | EQVF (2S7) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAW | IRTSGAN | NEQF (2S1) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAW | MR | DTQV (2S3) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | QGAGE | EQFF (2S1) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | VLS | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | VMAR | VEQV (2S7) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | VEGV | NEKL (1S4) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | VTGGQ | DTQV (2S3) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CAWS | DPGD | EQVF (2S7) | 1/15 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| BV14 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| ASSL | GQSR | ETQV (2S5) | 7/11 | ASSL | GQSR | ETQV (2S5) | 10/11 | ASSL | GQSR | ETQV (2S5) | 6/13 |

| ASS | RGQG | VEQV (2S7) | 1/11 | ASSL | FPTGR | EKLF (1S4) | 1/11 | ASSL | FPTGR | EKLF (1S4) | 4/13 |

| ASS | SVGGRS | EQFF (2S1) | 1/11 | — | — | — | — | ASSL | EGQT | SPLH (1S6) | 2/13 |

| ASS | IAGIRTLD | TDTQ (2S3) | 1/11 | — | — | — | — | ASS | FELAGGA | ETQV (2S5) | 1/13 |

| ASS | SSGGS | SVNE (2S1) | 1/11 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

BV-Cβ amplification of sorted CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells in a healthy donor was pursued. BV21, BV20, and BV14 were selected for the sequence analysis using the same PCR products. Eleven to 19 randomly chosen clones were sequenced per each PCR product.

— indicates no data.

Spectratypes of TCR BV21, BV20, and BV14.

Spectratyping analysis of αβ T cells within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα subpopulations was pursued in another healthy donor. Histograms of BV21, BV20, and BV14 are displayed as Figure 5.

Spectratypes of TCR BV21, BV20, and BV14.

Spectratyping analysis of αβ T cells within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα subpopulations was pursued in another healthy donor. Histograms of BV21, BV20, and BV14 are displayed as Figure 5.

As for BV21, 19 CDR3 cDNA clones of CD8α+βhigh cells were randomly selected and sequenced. Consistent with spectratyping, heterogeneous CDR3 clones were sequenced, which indicated that CD8α+βhigh cells possessing TCR Vβ21 were polyclonal. Conversely, a large number of cDNA clones were determined to be identical in CD8αα cells; in 9 of 16 clones the amino acid sequence of the N-D-N region was PVSGRL (designated as clone PVSGRL; single-letter amino acid codes). This clone was also identified in CD8α+βlow cells (3 of 16 clones). However, this clone PVSGRL was not found in the CD8α+βhigh subpopulation. Although an additional 46 cDNA clones within CD8α+βhighcells were analyzed, this clone was not detected (data not shown). In contrast, another clone, LDPSQGH, was detected within CD8α+βhigh cells and CD8α+βlow cells in the frequency of 2 of 19 and 3 of 16, respectively, but not within CD8αα cells. Notably, the third clone, FVSGS, was found within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα cells, although the clone was not dominant within these subpopulations (1 of 19, 3 of 16, and 2 of 16, respectively).

In BV20, a major clone, SPVSWA, within CD8αα cells (10 of 14 clones) dominated within CD8α+βlow cells (9 of 11 clones). This clone was also detected within CD8α+βhigh cells (2 of 15 clones). In BV14, where spectratypes of CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα subpopulations were all oligoclonal, clone GQSR was identified predominantly within the cells of all the subpopulations. To ensure that sharing of the identical clones among CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα subpopulations holds true for other individuals, we determined CDR3 sequences of BV17 from a different healthy donor; a dominant clone, SATVSYEQY, (7 of 10 clones) and a clone KPAGTFVLF (2 of 10 clones) within CD8αα cells were also detected within CD8α+βhigh cells at a frequency of 3 of 18 and 1 of 18, respectively (data not shown). Taken together, it is proved that the cells with skewed BV spectratypes, frequently observed in CD8α+βlow and CD8αα subpopulations, comprise oligoclonally proliferated cells. More importantly, CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells can possess the same cell clones. Some of these clones also become dominant with the loss of CD8β chains. These results suggest that some cell clones proliferate while down-regulating CD8β chains.

Sj TREC concentrations decreased with the down-regulation of CD8β

If CD8αα αβ T cells descend from CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells, CD8αα cells have undergone cell division more than CD8α+βlow, and still more than CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells. To assess the relative proliferative history of CD8+ αβ T-cell populations defined by the intensity of CD8β expression, we measured Sj TREC concentrations in CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T-cell subsets. In all 3 donors examined, Sj TREC levels were higher in CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells, and the number of Sj TREC copies declined with the loss of CD8β expression (Table2). These results, supporting the findings of spectratyping analysis, indicate that CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells, at least at the population level, can differentiate to CD8αα αβ T cells but not the opposite way.

Quantification of Sj TREC within CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells

| Donor . | Sj TREC/5 × 104 cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD8α+βhigh . | CD8α+βlow . | CD8αα . | |

| 1 | 140 | 76 | < 1 |

| 2 | 87 | 32 | < 1 |

| 3 | 160 | 20 | < 1 |

| Donor . | Sj TREC/5 × 104 cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD8α+βhigh . | CD8α+βlow . | CD8αα . | |

| 1 | 140 | 76 | < 1 |

| 2 | 87 | 32 | < 1 |

| 3 | 160 | 20 | < 1 |

Sj TREC concentrations were analyzed in 3 independent healthy donors.

Discussion

In the present paper, we tried to show that peripheral blood CD8αα or CD8α+βlow αβ T cells derive directly from CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells, presumably by an antigen-driven mechanism. Three different approaches were undertaken. At first, age-dependent changes in the proportions of CD8αα and CD8α+βlowαβ T cells were examined.

In cord blood, CD8αα αβ T cells were negligible and relatively small numbers of CD8α+βlow αβ T cells were detected. These populations increased with advancing age. They made up even about a half of the CD8α+ αβ T cells in some healthy adults. Neonatal T cells are exclusively composed of naive cells, and in repeated antigenic stimulations with age, infection and autoreactivity convert the naive cells to effector and memory cells.32 Therefore, CD8αα and CD8α+βlow αβ T cells may represent antigen-experienced cells. A wide range of the variation in the frequencies of these cells among adult individuals supports this notion.

Secondly, surface antigen expression, cytotoxic granule constituents, and cytokine production of CD8+ αβ T cells were assessed to characterize phenotype and functional features. The results of surface marker analysis were consistent with previous data that assessed surface expression of CD8αβ heterodimer on the positive and negative fractions of various antigens within CD8+ T cells.22 Several surface markers have been proposed for identification of naive, effector, and memory T cells. Although the CD45RA isoform can revert from CD45RO,33 double labeling with CD45RA and CD62L is frequently used for the identification of the cell phenotype.34,35 Alternatively, it is reported that simultaneous staining with CD45RA and CD27 mAbs can separate the majority of human CD8+ T cells into 3 functionally distinct subpopulations: CD45RA+ CD27+ cells, CD45RA+ CD27− cells, and CD45RA−CD27+ cells, which are naive, effector, and memory phenotype, respectively.36 Recently, naive T cells were identified as CD95− T lymphocytes.35 In addition, CCR7+ memory T cells were designated as central memory cells with the counterpart as effector memory cells.37 Considering data from these reports and that T cells reciprocally express CD45RA or CD45RO,38 the CD8α+βlow subpopulation contains effector memory cells. Although the CD8αα subpopulation exclusively comprised cells of the same surface phenotype as CD8α+βlow cells in more than half of the individuals analyzed, there were appreciable CD45RO−CCR7− cells within the CD8αα subpopulation in others. Because of the skewed spectratypes and low Sj TREC concentration, these CD45RO−CCR7− cells may represent terminally differentiated memory cells.39

Perforin, granzyme B, and TIA-1 expression were compatible with the surface phenotype of CD8α+βlowsubpopulations because the cytotoxic granule constituents are effector cell properties.40 Perforin and TIA-1 were also produced in CD8αα cells. It remains to be elucidated that CD8αα cells did not express granzyme B. As for cytokine production, both CD8α+βlow and CD8αα cells produced IFN-γ but not IL-2. Naive cells solely produce IL-2, and effector cells generate IFN-γ but not IL-2. Memory cells, on the contrary, produce both of them.36,41 However, IL-2 production is prominent in central memory cells; that of effector memory cells is significantly reduced.37 Therefore, the results of the cytokine production also support that CD8α+βlow and CD8αα αβ T cells are effector memory cells.

Thirdly, analysis of CDR3 length diversity can be used to define the extent of clonal expansion within the TCR repertoire.42,43The TCR Vβ CDR3 complexity decreased in CD8+ T cells with diminished CD8β expression. The results suggest that CD8α+βlow and, moreover, CD8αα αβ T cells have proliferated extensively probably by antigenic stimulations. Also, the history of cell proliferation can be assessed by Sj TREC concentrations. Sj TRECs are the episomal DNA circles generated during excisional rearrangement of TCR genes.44 Not replicating during mitosis, they are diluted during cell division.45 46 Sj TREC value was significantly higher in CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells but reduced with the loss of CD8β chains, consistent with decrease in TCR Vβ CDR3 complexity. These data collectively indicated that CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells diminish the CD8β-chain expression as they are activated, proliferate, and acquire memory phenotypes and functions in vivo.

To prove directly that particular CD8+ T cells change the levels of β-chain expression in vivo, we tried to clarify that the same clones exist among CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells, and pursued TCR Vβ CDR3 sequence analysis. The CDR3 forms the contact site for binding to MHC expressed by antigen-presenting cells. The region bears the fine specificity of antigen recognition.47-50 Therefore, the CDR3 sequence defines a distinctive TCR clonotype that acts as a fingerprint for the T-cell lineage bearing it.51 On the basis of TCR Vβ CDR3 spectratyping and their sequences, recent studies proposed that identical T-cell clones are located within the mouse gut epithelium and lamina propria and circulate in the thoracic duct lymph,52or that CD8+CD28− T cells descend directly from CD8+CD28+ T cells in humans.53 54 In the experiment presented here, the same clones were identified among CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells in all of 3 BVs analyzed. Because the major clones sequenced within CD8αα cells were not identified within the CD8α+βhigh subset in BV21, it is unlikely that clones sequenced within the CD8α+βhighsubpopulation are derived from missorted CD8αα αβ T cells. This result may rather be explained by the fact that all cells of the clone have already down-regulated CD8β. Missorting can neither explain the result in BV14, which showed that the major clones sequenced among CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells were identical. Therefore, the sequence result suggests CD8α+βhigh, CD8α+βlow, and CD8αα αβ T cells can share the same clones. Considering the differentiation stage, spectratypes, Sj TREC concentration, and CDR3 sequences, CD8αα and CD8α+βlow αβ T cells do not belong to different ontogenic lineages, but directly descend from CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells.

In contrast to our data, numerous studies have suggested that CD8αα cells are extrathymically differentiated T cells.20-22,55CD8αα T cells reside in intestinal mucosa, and they are proved to be thymus independent.56-58 In bone marrow transplantation (BMT), about one half of the CD8+ T cells constituted from T cell–depleted marrow were CD8αα cells in thymectomized recipient mice.20 As for human children, older patients at BMT exhibited more CD8αα T cells than younger ones, suggesting the influence of thymic function on the regenerative pathways.21 However, these findings do not indicate that all of the CD8αα αβ T cells are necessarily of extrathymic origin. At least peripheral CD8αα αβ T cells and CD8αα αβ T intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) should be considered distinctively. It is reported that TCRαβ CD8αα IELs have not previously expressed CD8β using DNA methylation pattern analysis.59 Indeed, the results of IEL TCR Vβ CDR3 analysis turned out to be opposite to those presented in this study; TCRαβ IELs bearing CD8αβ or CD8αα coreceptors shared no TCR BV clone.52 60

However, most recent studies by Leishman et al23 and Devine et al24 concerning the fate and function of these unique CD8+ T-cell subpopulations strongly indicate that they derive from the thymus and are positively selected. Moreover, CD8αα phenotype was shown to be acquired under the influence of the microenvironment of intraepithelial lymphoid tissue.25Furthermore, they suggest that CD8α+βlowand CD8αα αβ T cells exhibit unique functional roles in vivo distinct from CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells. Our findings are consistent with these data and confirm the notion that all 3 CD8+αβ T cells belong to the same cellular lineage and the level of CD8β chain expression is secondarily regulated in vivo by antigenic stimulation and subsequent cell activation.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the CD8αα and CD8α+βlow αβ T cells are effector memory or terminally differentiated CD45RO−CCR7− memory cells. Moreover, these cells share the same clone with the usual CD8α+βhigh αβ T cells. We propose that at least in healthy individuals, circulating CD8αα and CD8α+βlow αβ T cells do emerge as a consequence of MHC-TCR interaction. Therefore, the persistence of these cells reflects the presence of continuous antigenic stimulations and subsequent accumulation of the antigen-specific clonally expanded T cells, which may be influenced by thymic output. Analysis of these cells may help us to understand the pathogenesis of autoimmunity and immunodeficiency, and it will provide a useful biomarker to evaluate the disease activities.

We thank Ms Mika Kitakata, Ms Tamae Yonezawa, and Ms Harumi Matsukawa for excellent technical help.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 25, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1136.

Supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan; and a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan, Tokyo.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Akihiro Yachie, 13-1 Takara-machi, Kanazawa, 920-8641 Japan; e-mail:yachie@med.kanazawa-u.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal