Abstract

Cotreatment with a minimally toxic concentration of the protein kinase C (PKC) activator (and down-regulator) bryostatin 1 (BRY) induced a marked increase in mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in U937 monocytic leukemia cells exposed to the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin (LC). This effect was blocked by cycloheximide, but not by α-amanitin or actinomycin D. Qualitatively similar interactions were observed with other PKC activators (eg, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and mezerein), but not phospholipase C, which does not down-regulate the enzyme. These events were examined in relationship to functional alterations in stress (eg, SAPK, JNK) and survival (eg, MAPK, ERK) signaling pathways. The observations that LC/BRY treatment failed to trigger JNK activation and that cell death was unaffected by a dominant-interfering form of c-JUN (TAM67) or by pretreatment with either curcumin or the p38/RK inhibitor, SB203580, suggested that the SAPK pathway was not involved in potentiation of apoptosis. In marked contrast, perturbations in the PKC/Raf/MAPK pathway played an integral role in LC/BRY-mediated cell death based on evidence that pretreatment of cells with bisindolylmaleimide I, a selective PKC inhibitor, or geldanamycin, a benzoquinone ansamycin, which destabilizes and depletes Raf-1, markedly suppressed apoptosis. Furthermore, ERK phosphorylation was substantially prolonged in LC/BRY-treated cells compared to those exposed to BRY alone, and pretreatment with the highly specific MEK inhibitors, PD98059, U0126, and SL327, opposed ERK activation while protecting cells from LC/BRY-induced lethality. Together, these findings suggest a role for activation and/or dysregulation of the PKC/MAPK cascade in modulation of leukemic cell apoptosis following exposure to the proteasome inhibitor LC.

Introduction

Mammalian cells, both normal and neoplastic, undergo apoptosis in response to a variety of stimuli, including DNA damage, cytokine deprivation, and dysregulation of oncoproteins.1-3 Survival is governed by a family of regulatory proteins, whose expression is modified by cellular signals; together, these determine whether cells undergo differentiation, proliferation, or apoptosis.4,5 Such cellular signals exert either cytoprotective or cytotoxic actions, depending on the specific downstream pathways affected (ie, stress-activated protein kinase [SAPK] or mitogen-activated protein kinase [MAPK]). There is accumulating evidence that the dynamic balance between the proapoptotic JNK (c-Jun N-termina kinase)/p38 (SAPK) pathway and the growth and differentiation-associated ERK (extracellular receptor kinase; MAPK) pathway represents an important determinant of cell survival or death.6 Recently we have shown that in U937 and HL-60 human leukemia cells, the extent of apoptosis depends on the coordinate regulation of the SAPK and MAPK cascades.7 In view of their potential importance in regulating neoplastic cell survival, these signaling pathways are currently the subject of intense interest as potential targets for chemomodulation.

Bryostatin 1 (BRY), a macrocyclic lactone isolated from the marine invertebrate Bugula neritina, has shown significant antitumor activity in preclinical studies8-10 and is currently undergoing clinical evaluation in humans.11,12BRY acutely activates protein kinase C (PKC), whereas prolonged exposure of cells to this compound potently down-regulates enzyme activity.13,14 The mechanism by which BRY induces down-regulation of PKC has recently been attributed to ubiquitination of cPKCα and subsequent targeting of the protein to the proteasome.15 Chronic exposure to BRY, which weakly induces differentiation in U937 and HL-60 cells,16,17enhances certain forms of drug-induced apoptosis in these lines, presumably through modulation of the PKC/MAPK signaling cascade.7,18 This finding is consistent with the observations that inhibitors of PKC are among the most potent inducers of cell death in both leukemic and nonhematopoietic cells,19 and lower the threshold for drug-mediated apoptosis.20

The ubiquitin-proteasome system provides a major mechanism by which intracellular proteins are degraded.21,22 Furthermore, proteasomal inhibitors induce apoptosis in diverse cell types,23,24 suggesting an important role for the proteasome in the regulation of cell survival.25 However, the mechanism by which proteasome inhibitors induce cell death remains obscure. In a recent communication, Song et al reported that the proteasome inhibitor MG132 blocked BRY-mediated differentiation and p53 phosphorylation/degradation in the promyelocytic leukemic cell line NB4, and that these effects were mimicked by the specific MAPK inhibitor PD98059.26 Such findings raise the possibility that interactions between BRY and the ubiquitin/proteasome system may proceed through a MAPK-dependent pathway, at least as far as cellular maturation is concerned.

The present studies were prompted by a desire to define the role of bryostatin-induced PKC down-regulation in the cell death process more rigorously, with particular emphasis on apoptosis induced by disruption of proteasome function. A second goal was to relate these events to functional alterations in stress (eg, SAPK) and survival (eg, MAPK) signaling pathways. To this end, we have used lactacystin (LC), aStreptomyces product known to inhibit proteasome function in diverse systems.21 27 Here we report that exposure of U937 monocytic leukemia cells to a minimally toxic concentration of BRY (or, to a lesser extent, the tumor promoters phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate [PMA] or mezerein [MEZ]) results in a dramatic potentiation of apoptosis in LC-treated cells. Evidence obtained from a cell line expressing TAM67, a c-Jun transactivation domain-deficient mutant protein, and studies using the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580, suggest that this interaction does not involve signaling through the c-Jun/AP1 or p38/RK pathways. In marked contrast, enhanced apoptosis in LC/BRY-treated cells is temporally associated with sustained MAPK activation and is substantially attenuated by agents that disrupt the PKC/Raf/MEK/EPK cascade, including bisindolylmaleimide I, geldanamycin, PD98059, U0126, and SL327. Collectively, these findings suggest a functional role for activation/dysregulation of the PKC/MEK/EPK module in the synergistic induction of leukemic cell apoptosis by LC/BRY.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The human monoblastic leukemia cell line U937, derived from a patient with diffuse histiocytic lymphoma,28 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1.0% pyruvate, nonessential amino acids, l-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (all from GIBCO/BRL, Grand Island, NY) and maintained as previously described.16Stable U937 transfectants expressing TAM67 (a c-Jun transactivation domain-deficient mutant that retains normal DNA binding and dimerization functions) along with their empty-vector counterparts, were used as previously described.29 A U937 cell line that exhibits dysregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI) p21WAF1/CIP1 by stable expression of a pREP4 antisense p21WAF1/CIP1 construct (p21AS) has also been described in detail.30 All transfectants were maintained under appropriate selection pressure (200 μg/L hygromycin or 400 μg/mL G418).

Drugs and reagents

Cells in logarithmic-phase growth were suspended at 2 × 105 cells/mL and exposed to test agents for various intervals as indicated. In the experimental paradigm, lactacystin was added 0.5 hour before the addition of the second agent. Pretreatment permits conversion of lactacystin to its active derivative, β-lactone, and subsequent entry into the cell.31 In experiments involving protein, RNA, and kinase inhibitors, cells were pretreated with each inhibitor 0.5 to 1 hour before the addition of lactacystin. The agents were obtained from the following sources: bryostatin 1 (provided by Dr A. J. Murgo, CTEP-NCI); actinomycin D, α-amanitin, cycloheximide, geldanamycin,l-N-acetylcysteine (L-NAC), MEZ, phospholipase C(Bacillus cereus), PMA (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO); lactacystin and 4α-PMA (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA); transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); bisindoylmaleimide I (GF109203X) and SB203580 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA); and curcumin and PD98059 (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA). U0126 and SL327 were generously provided by Dr James Trzaskos (DuPont/Merck Research Laboratories, Wilmington, DE).

Assessment of apoptosis

Cell morphology and apoptosis was monitored by examining cytocentrifuge preparations stained with the Diff-Quik stain set (Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL) by light microscopy, or by TUNEL staining and fluorescent microscopy, as previously described.32 For each study, triplicate experiments were performed in which a total of 15 randomly selected fields, encompassing at least 1500 cells, were evaluated for each condition. In some cases the extent of apoptosis was confirmed by size threshold readings on a Coulter Z2 channelyzer (Opa Locka, FL).

Clonogenic assays

Following drug treatment for 24 hours, cell number was determined by hemacytometer count, and cells were washed 3 times in drug-free medium. Their ability to form colonies in soft agar was determined by a previously described technique.33Colonies, consisting of groups of 50 cells, were scored at day 10 using an Olympus (Melville) Model CK inverted microscope.

Western blot analysis

Treated cells were washed once in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and either lysed in 1 × Laemmli buffer and immunoblotted for procaspase 3, Raf-1 (both 1:1000; Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA), PARP (1:1000; Biomol), PKCα, PKCβI, PKCβII (all 1:3000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), actin (1:4000; Sigma), tubulin (1:2000; Sigma), or as per the manufacturer's instructions for phospho-ERK, ERK, and phospho-JNK (all 1:2000; New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). Proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using either 25 μg cell extracts or 5 × 105cell equivalents.

Assessment of mitochondrial function/integrity

At the indicated intervals, cells were harvested and 2 × 105 cells were incubated with 40 nM 3,3-dihexyloxacarbocyanine (DiOC6; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 15 minutes at room temperature, as previously described.30 Cells were analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan cytofluorometer and the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6 relative to control cells, reflecting loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, was determined using CyCLOPS 2000 Version 4.0 software.

PKC activity

The SignaTECT PKC assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) was used as per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, drug-treated cells were washed 1 × with cold PBS, lysed on ice in cold extraction buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.05% Triton X-100, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 μg/mL leupeptin/aprotinin, and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) and sonicated. Total cell lysate was centrifuged at 4°C for 5 minutes at 14 000g and 50 μg supernatant was incubated in coactivation buffer (0.25 mM EGTA, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin [BSA]), 0.1 mM ATP, 0.5 μCi γ32P] ATP (3000 Ci/mmol), and 100 μM PKC biotinylated peptide substrate in the presence or absence of activation buffer (0.32 mg/mL phosphatidylserine, 0.032 mg/mL diacylglycerol, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2) for 5 minutes at 30°C. Reactions were terminated by the addition of guanidine hydrochloride (2.5 M) and spotted on SAM2 membrane. Purified PKC was used as a positive control and myristoylated PKC peptide inhibitor was used to indicate specificity. Values are expressed as the percentage of PKC activity relative to those of untreated cell extract (100%).

Statistical analysis

The significance of differences between experimental groups was determined using the Student t test for unpaired observations. To assess the interaction between agents, Median Dose Analysis was used34 with a commercially available software program (CalcuSyn; Biosoft, Ferguson, MO). The combination index (CI) was calculated for a 2-drug combination involving a fixed concentration ratio. Using these methods, CI values less than 1.0 indicate a synergistic interaction.

Results

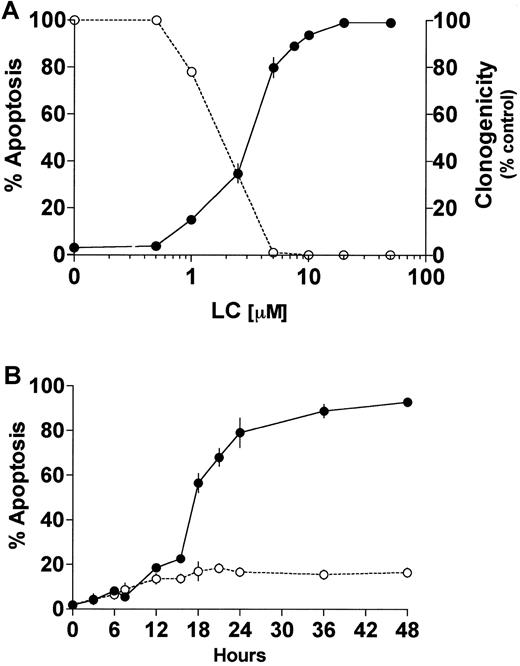

BRY potentiates LC-induced apoptosis in U937 cells

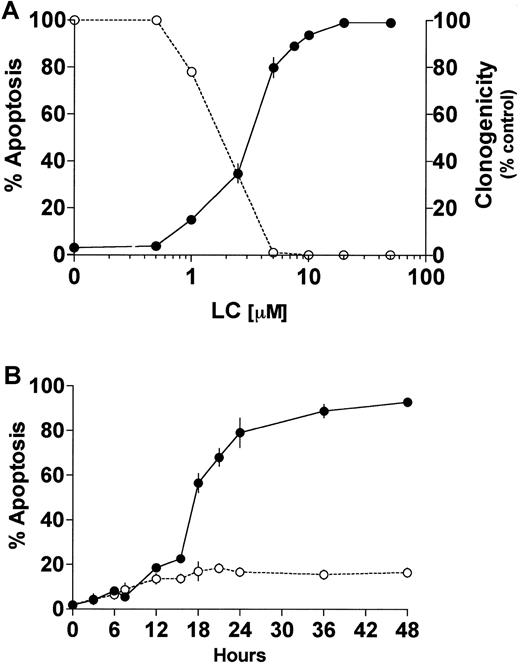

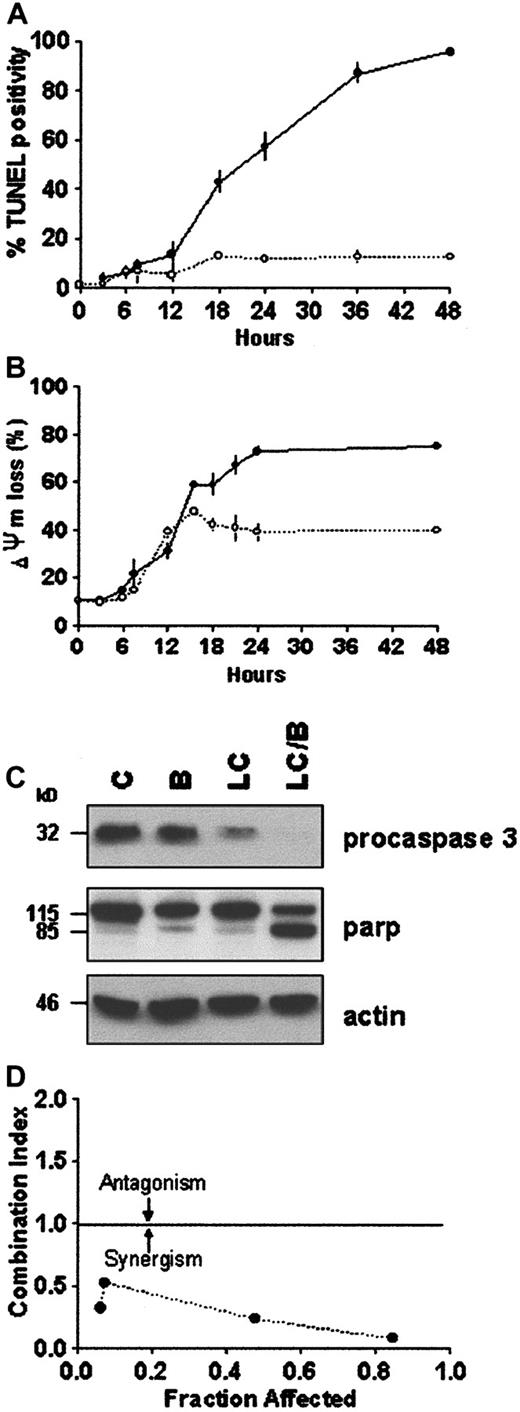

Proteasome inhibitors induce apoptosis in proliferating cells,23,24,35 whereas in differentiated neuronal cells or thymocytes they inhibit cell death.36,37 In U937 human leukemic cells, the proteasome inhibitor LC induces caspase 3-dependent cell death.24,38 Furthermore, it has been previously reported that induction or inhibition of cell death by proteasome inhibitors is highly concentration dependent.39 The data in Figure 1A demonstrate that exposure of U937 cells to LC for 24 hours induces apoptosis and reciprocally reduces leukemic self-renewal capacity in a concentration-dependent manner. The LC concentration producing 50% apoptosis was approximately 3 μM. To assess the effects of PKC down-regulation on the response to LC, cells were exposed to a marginally toxic concentration of LC (∼15% cell death; 1 μM) for 24 hours in conjunction with a concentration of BRY (10 nM) previously shown to reduce total cellular PKC activity by more than 90% in this cell line.32Concurrent treatment with BRY (24 hours), which by itself was minimally toxic (8%-10% apoptosis; data not shown), dramatically enhanced LC-mediated lethality, manifested by potentiation of the morphologic features of apoptosis (Figure 1B). In addition, BRY potentiated other aspects of LC-induced cell death, including DNA fragmentation (Figure2A), loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm; Figure 2B), marked degradation/activation of procaspase-3, and cleavage of the major caspase-3 substrate, PARP (Figure 2C). Following exposure to LC and BRY, apoptosis was most apparent after 18 hours of treatment, whereas enhanced loss of mitochondrial membrane potential was observed as early as 12 hours after drug exposure. It should be noted that treatment with 1 μM LC alone induced a moderate degree of mitochondrial membrane discharge (∼40%), which was evident at 12 hours but did not increase further; in contrast, BRY induced less than 15% mitochondrial discharge at all time intervals examined (not shown). Lastly, median dose effect analysis was used to characterize the interaction between BRY and LC with respect to induction of apoptosis. Varying concentrations of LC (0.1-2 μM) and BRY (0.5-10 nM) administered at a fixed ratio (1:5) resulted in CI values less than 1, indicating a synergistic interaction (Figure 2D). In separate studies, BRY did not potentiate apoptosis by other protease inhibitors, including NH4Cl (2 mM), E64 (1, 10 μM), leupeptin (10 μM), calpain inhibitor I (1 μM), or calpain inhibitor II (10 μM) (data not shown), nor did these inhibitors induce apoptosis by themselves, indicating that inhibition of lysosomal, thiol, and cysteine proteases is not involved in the initiation of apoptosis. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that LC and BRY interact synergistically in a specific manner to induce apoptosis in U937 cells.

LC induces cell death and loss of clonogenicity in U937 cells.

(A) U937 cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) were exposed to LC at increasing concentrations for 24 hours and then either assayed for apoptosis as determined by morphologic analysis of Wright-Giemsa stained cytospins (●) or their self renewal capacity by their ability to form colonies in soft agar (○). (B) U937 cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) were exposed to 1μM LC (○) and LC plus 10 nM BRY (●) for the indicated intervals, and apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis of Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins. Exposure to BRY alone induces approximately 8% to 10% apoptosis (not shown). Values represent means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

LC induces cell death and loss of clonogenicity in U937 cells.

(A) U937 cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) were exposed to LC at increasing concentrations for 24 hours and then either assayed for apoptosis as determined by morphologic analysis of Wright-Giemsa stained cytospins (●) or their self renewal capacity by their ability to form colonies in soft agar (○). (B) U937 cells (2 × 105 cells/ml) were exposed to 1μM LC (○) and LC plus 10 nM BRY (●) for the indicated intervals, and apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis of Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins. Exposure to BRY alone induces approximately 8% to 10% apoptosis (not shown). Values represent means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

BRY potentiates LC-induced apoptosis in U937 cells.

U937 cells (2 × 105 cells/mL) were exposed to 1 μM LC (○) and LC plus 10 nM BRY (●) for the indicated intervals. (A) DNA fragmentation was assessed by the percentage of cells exhibiting TUNEL positivity. (B) Cytotoxicity was measured by the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6, reflecting loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. Values represent means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (C) Western blots illustrating degradation/activation of procaspase 3 and PARP cleavage in extracts from treated cells. (D) Morphologic evidence of apoptosis (monitored at 24 hours) were used as the end-point in conjunction with median dose effect analysis to characterize drug interactions. Varying concentrations of LC (0.1-2 μM) and BRY (0.5-10 nM) at a fixed ratio (1:5) resulted in CI values less than 1. Values correspond to the results of a representative experiment.

BRY potentiates LC-induced apoptosis in U937 cells.

U937 cells (2 × 105 cells/mL) were exposed to 1 μM LC (○) and LC plus 10 nM BRY (●) for the indicated intervals. (A) DNA fragmentation was assessed by the percentage of cells exhibiting TUNEL positivity. (B) Cytotoxicity was measured by the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6, reflecting loss of mitochondrial membrane potential. Values represent means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (C) Western blots illustrating degradation/activation of procaspase 3 and PARP cleavage in extracts from treated cells. (D) Morphologic evidence of apoptosis (monitored at 24 hours) were used as the end-point in conjunction with median dose effect analysis to characterize drug interactions. Varying concentrations of LC (0.1-2 μM) and BRY (0.5-10 nM) at a fixed ratio (1:5) resulted in CI values less than 1. Values correspond to the results of a representative experiment.

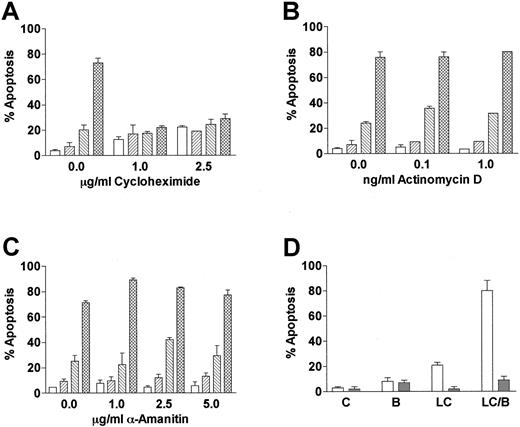

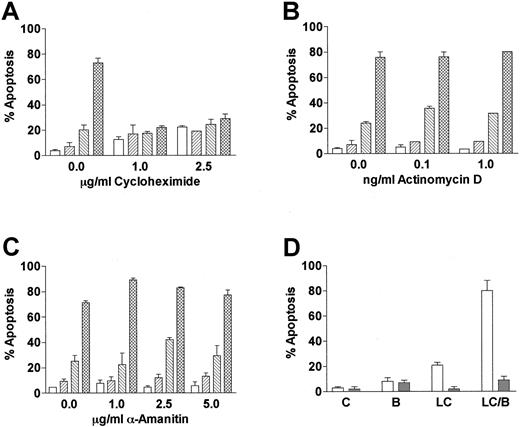

LC- and BRY-mediated apoptosis is protein synthesis dependent

Cells incubated with proteasome inhibitors display an increase in proteins that are normally degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. To determine if LC/BRY-induced apoptosis depended on the accumulation of either new or preexisting cellular proteins, U937 cells were pretreated with varying concentrations of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide prior to the addition of LC/BRY (Figure 3A). In marked contrast to the results of previous reports, which have shown that cycloheximide renders U937 cells more sensitive to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced apoptosis40 and does not inhibit VP-16–induced cell death in HL-60 cells,41 the enhanced apoptotic response to LC/BRY was completely abolished by cycloheximide. However, inhibition of RNA synthesis with α-amanitin or actinomycin D did not prevent BRY from potentiating LC-induced cell death (Figure3B,C). These findings suggest that apoptosis induced by LC/BRY treatment involves a protein synthesis-dependent but transcription-independent process. Lastly, coadministration of the reduced glutathione (GSH) precursor L-NAC (5 mM, Figure 3B, or 2.5 mM, data not shown) effectively blocked both LC- and LC/BRY-induced apoptosis, raising the possibility that generation of reactive oxygen species may be involved in the enhanced apoptosis induced by these agents.

LC/BRY-mediated apoptosis requires new protein synthesis.

(A) U937 cells were pretreated with varying concentrations of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (1 hour) prior to the addition of LC plus BRY (24 hours). Apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis of Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins. (B,C) Cells were pretreated with varying concentrations of the RNA synthesis inhibitors α-amanitin or actinomycin D (1 hour) prior to LC/BRY exposure. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). Vehicle (open bar), BRY (left-hatched bar), LC (right-hatched bar), LC plus BRY (cross-hatched bar). (D) Cells were exposed to LC (BRY as above in the presence or absence of 5 mM L-NAC, after which the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined as previously described. Values represent the means for 3 separate experiments (± SEM).

LC/BRY-mediated apoptosis requires new protein synthesis.

(A) U937 cells were pretreated with varying concentrations of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (1 hour) prior to the addition of LC plus BRY (24 hours). Apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis of Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins. (B,C) Cells were pretreated with varying concentrations of the RNA synthesis inhibitors α-amanitin or actinomycin D (1 hour) prior to LC/BRY exposure. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). Vehicle (open bar), BRY (left-hatched bar), LC (right-hatched bar), LC plus BRY (cross-hatched bar). (D) Cells were exposed to LC (BRY as above in the presence or absence of 5 mM L-NAC, after which the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined as previously described. Values represent the means for 3 separate experiments (± SEM).

LC-BRY–induced apoptosis does not depend on an intact c-Jun/AP-1 signaling pathway

Although previous studies have suggested that JNK activation is essential for apoptosis induced by proteasome inhibitors in general, and LC in particular,42 an increase in phospho-JNK expression following either LC or LC/BRY treatment could not be demonstrated (data not shown). In contrast, HSP72 expression was increased following exposure to LC as reported previously in the case of MG132,42 but BRY did not enhance this effect (data not shown). To examine the functional role of this pathway in LC/BRY-mediated cell death, U937 cells stably expressing a dominant-negative c-Jun construct (TAM67)43 were used. This construct contains the DNA binding domain but lacks the AP-1 transactivation domain, thereby blocking an immediate downstream target of the JNK cascade. U937/TAM67 cell lines, and their empty vector controls, were exposed to LC/BRY for 24 hours, after which apoptosis and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential were assessed (Figure4A,B). In the control and both TAM67 subclones, combined LC/BRY treatment induced apoptosis in about 80% of cells (Figure 4A) and exhibited equivalent loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 4B). In separate control studies, expression of the TAM67 protein substantially protected cells from sphingomyelinase-induced (100 mU/mL) apoptosis, as previously reported7 (data not shown). One of the TAM67 subclones exhibited slight protection against apoptosis induced by LC alone, a finding analogous to that previously described in the case of human kidney 293 cells transfected with the TAM67 construct.42Lastly, cells pretreated with curcumin (0.5 μM; 24 hours), an agent that blocks the JNK/AP-1 pathway by interfering with MEKK or other upstream signals,44 also failed to protect cells against LC/BRY-induced apoptosis (data not shown). The failure of a dominant negative c-Jun construct or pharmacologic disruption of the JNK/AP1 pathway to protect against enhanced apoptosis following LC/BRY treatment argues against the involvement of c-Jun/AP1 signaling in this phenomenon.

The SAPK cascade is not involved in LC/BRY-induced apoptosis.

(A,B) U937 cell lines expressing a dominant negative construct of c-Jun (TAM67: clone 1-1 [left-hatched bar], clone 2-2 [cross-hatched bar]), and their empty vector controls (open bar) were exposed to either vehicle, bryostatin (B; 10 nM), lactacystin (LC; 1 μM) or the combination lactacystin plus bryostatin (LC/B) for 24 hours. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments and are (A) expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells determined by morphologic analysis or (B) loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, expressed as the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6 uptake. (C) U937 cells were pretreated with the specific p38/RK inhibitor SB203580 (SB; 10 or 20 μM) 30 minutes prior to the addition of LC plus BRY (LC/B). Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

The SAPK cascade is not involved in LC/BRY-induced apoptosis.

(A,B) U937 cell lines expressing a dominant negative construct of c-Jun (TAM67: clone 1-1 [left-hatched bar], clone 2-2 [cross-hatched bar]), and their empty vector controls (open bar) were exposed to either vehicle, bryostatin (B; 10 nM), lactacystin (LC; 1 μM) or the combination lactacystin plus bryostatin (LC/B) for 24 hours. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments and are (A) expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells determined by morphologic analysis or (B) loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, expressed as the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6 uptake. (C) U937 cells were pretreated with the specific p38/RK inhibitor SB203580 (SB; 10 or 20 μM) 30 minutes prior to the addition of LC plus BRY (LC/B). Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

LC/BRY-induced apoptosis does not require p38/RK signaling

Although the p38/RK signaling cascade is activated in response to proteasome inhibitors, this pathway is reportedly not involved in proteasome inhibitor-induced cell death.42 To determine if potentiation of LC-induced apoptosis involved p38/RK, cells were pretreated with the specific p38/RK inhibitor SB203580 before the addition of LC/BRY. Neither 10 nor 20 μM SB203580 inhibited apoptosis induced by LC alone (not shown) or by LC/BRY (Figure 4C), suggesting that p38/RK signaling does not mediate U937 cell death induced by either LC or the combination of LC/BRY.

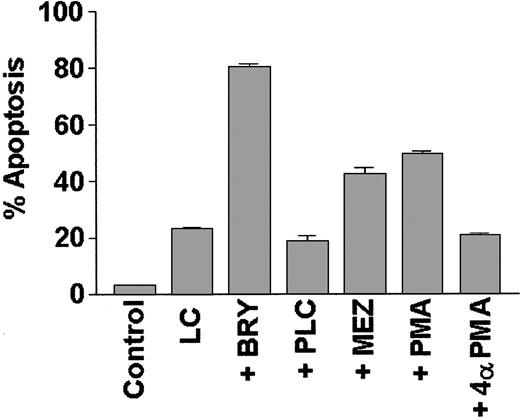

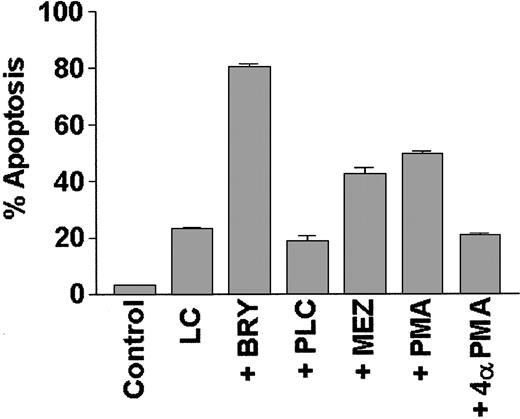

Potentiation of LC-mediated apoptosis by BRY requires PKC activation

To determine if potentiation of LC-induced apoptosis could be generalized to include other agents that activate the PKC/MAPK pathway, or is instead restricted to BRY, induction of cell death was monitored in cells treated with LC in conjunction with other well-characterized PKC activators (Figure 5). Of these, PMA and MEZ (but not the negative control 4α-PMA) significantly increased apoptosis in LC-treated cells, although the extent of potentiation was somewhat less than that observed with BRY. In contrast, cotreatment with bacterial phospholipase C (PLC), which acutely activates PKC via the generation of endogenous diaglycerides, failed to enhance LC-induced cell death; instead, it marginally protected cells from LC-induced apoptosis (P = .05 versus LC alone). These studies demonstrate that agents, which, on chronic exposure, down-regulate PKC (eg, BRY, PMA, MEZ) potentiate LC-induced apoptosis, whereas an agent known to induce sustained activation of PKC (eg, PLC) fails to do so.

The PKC activators BRY, PMA, and MEZ, but not PLC, promote apoptosis in LC-treated cells.

U937 cells (2 × 105 cells/mL) were exposed to lactacystin (LC; 1 μM) and either bryostatin (BRY; 10 nM), phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 10 nM), mezerein (MEZ; 10 nM), phospholipase C (PLC; 200 mU/mL), or an inactive phorbol control (4α-PMA; 10 nM) for 24 hours. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM) and are expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells determined by morphologic analysis.

The PKC activators BRY, PMA, and MEZ, but not PLC, promote apoptosis in LC-treated cells.

U937 cells (2 × 105 cells/mL) were exposed to lactacystin (LC; 1 μM) and either bryostatin (BRY; 10 nM), phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 10 nM), mezerein (MEZ; 10 nM), phospholipase C (PLC; 200 mU/mL), or an inactive phorbol control (4α-PMA; 10 nM) for 24 hours. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM) and are expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells determined by morphologic analysis.

To define the role of PKC activation in this phenomenon further, a highly selective inhibitor of PKC, bisindolylmaleimide I (GF109203X), was used to inhibit basal and BRY-related activation of PKC. Pretreatment of cells with GFX (1 μM; 0.5 hour) prior to the addition of LC/BRY dramatically inhibited apoptosis (eg, by ∼60%; Figure6A). To establish whether the duration of PKC activation by BRY represented an important determinant of LC/BRY-mediated cell death, GFX was added at increasing exposure intervals following treatment of cells with LC/BRY (Figure 6A). The enhanced apoptotic response was abrogated when GFX was added at early intervals following BRY (eg, < 4 hours), whereas at later time points (eg, > 6 hours) BRY retained its ability to potentiate cell death in LC-treated cells. These findings suggest that the initial activation of PKC by BRY plays a critical role in its ability to augment LC-mediated apoptosis.

The ability of BRY to potentiate LC-induced apoptosis is PKC dependent.

(A) U937 cells were either pretreated or posttreated with the specific PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (GF109203X; 1 μM), as indicated. Cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation at 24 hours and the extent of apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis. [o] indicates the extent of cell death observed in cells treated with LC alone and [*] indicates the extent observed in LC/B-treated cells. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (B) U937 cells were exposed to either media (C), BRY (10 nM) (B), LC (1 μM) or the LC/BRY combination (LC/B) for 24 hours. The amount of phorbol-activated PKC activity remaining was then determined. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (C) Western blots of PKC isoform expression (PKCα, PKCβI, and PKCβII) at the indicated intervals following drug exposure.

The ability of BRY to potentiate LC-induced apoptosis is PKC dependent.

(A) U937 cells were either pretreated or posttreated with the specific PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (GF109203X; 1 μM), as indicated. Cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation at 24 hours and the extent of apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis. [o] indicates the extent of cell death observed in cells treated with LC alone and [*] indicates the extent observed in LC/B-treated cells. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (B) U937 cells were exposed to either media (C), BRY (10 nM) (B), LC (1 μM) or the LC/BRY combination (LC/B) for 24 hours. The amount of phorbol-activated PKC activity remaining was then determined. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (C) Western blots of PKC isoform expression (PKCα, PKCβI, and PKCβII) at the indicated intervals following drug exposure.

Lactacystin (50 μM) prevents BRY-induced down-regulation of PKC in renal epithelial cells and fibroblasts.15,45 To determine whether the LC/BRY doses and exposure intervals used in the present studies produced a similar response, PKC activity and isoform expression was monitored following 24 hours of exposure of cells to LC/BRY (Figure 6B,C). U937 cells exposed to BRY for 24 hours displayed an approximately 70% decrease in PKC activity, whereas LC-treated cells exhibited only a marginal decrease (< 10%; Figure 6B). In contrast to previous findings,15 45 LC did not prevent BRY-induced down-regulation of PKC activity inasmuch as combination treatment produced an approximate 80% decrease in enzyme activity. Consistent with these results, PKC isoform expression revealed decreased levels of PKCα, PKCβI, and PKCβII following a 24-hour exposure to BRY (Figure 6C). Cotreatment of cells with LC and BRY did not block this effect. These findings demonstrate that a minimally toxic concentration of LC (eg, 1 μM) does not antagonize BRY-mediated PKC down-regulation in U937 cells.

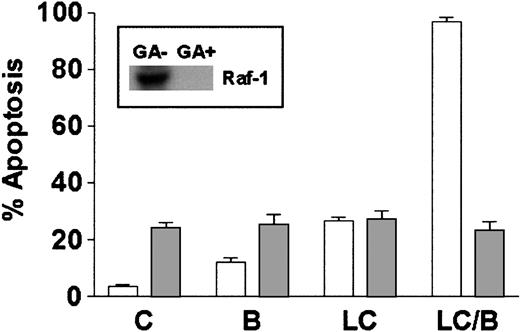

Raf-1 is essential for LC/BRY-induced apoptosis

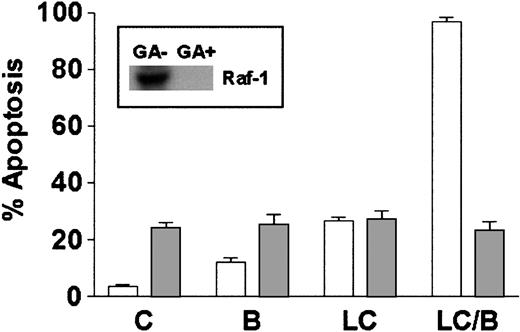

Studies using dominant-negative and constitutively active PKC mutants have shown that activation of Raf-1 represents a critical component of signaling through the PKC/MAPK pathway.46 In addition, BRY actives Raf-1 in a PKC-dependent manner through direct serine phosphorylation.47 To determine if Raf-1 activation was essential for potentiation of LC-induced cell death by BRY in U937 cells, geldanamycin, a benzoquinone ansamycin that binds to HSP-90 and disrupts the Raf-1/HSP90 complex, resulting in Raf-1 destabilization,48 was used to interrupt this pathway. Cells were either pretreated with 1 μM geldanamycin for 18 hours before the addition of LC/BRY or were treated acutely with LC/BRY. Geldanamycin pretreatment reduced Raf-1 protein expression to undetectable levels (Figure 7, inset). Concomitant with decreased levels of Raf-1 protein, the extent of apoptosis in LC/BRY-treated cells was reduced to levels observed in cells exposed to geldanamycin alone (Figure 7). Moreover, cells treated simultaneously with geldanamycin and LC/BRY (ie, without the 18-hour preincubation interval) exhibited an approximate 40% decrease in apoptosis (P = .05 compared to LC/BRY alone; data not shown). These results suggest that Raf-1 plays a critical role in the enhanced apoptosis observed in U937 cells exposed to LC/BRY.

Depletion of Raf-1 opposes LC/BRY-induced apoptosis.

U937 cells were exposed to 1 μM geldanamycin for 18 hours before the addition of either vehicle (C), BRY (B; 10 nM), LC (1 μM), or LC plus BRY (LC/B). Inset indicates the level of Raf-1 expression in cells after 18 hours and before drug treatments. The bar graph illustrates the extent of apoptosis at 24 hours after treatment as determined by morphologic analysis. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

Depletion of Raf-1 opposes LC/BRY-induced apoptosis.

U937 cells were exposed to 1 μM geldanamycin for 18 hours before the addition of either vehicle (C), BRY (B; 10 nM), LC (1 μM), or LC plus BRY (LC/B). Inset indicates the level of Raf-1 expression in cells after 18 hours and before drug treatments. The bar graph illustrates the extent of apoptosis at 24 hours after treatment as determined by morphologic analysis. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

ERK activation is essential for potentiation of LC-mediated apoptosis by BRY

MEK (MAPK/ERK kinase), a physiologic substrate of Raf-1, phosphorylates and activates ERK1/2,49 which in turn phosphorylates multiple downstream targets. Proteasome inhibitors have been shown to enhance MAPK activation through prolonged translocation of MAPK to the nucleus.50 To determine whether cells exposed to LC exhibit altered MAPK activation in response to BRY treatment, levels of phosphorylated (ie, activated) ERK1 and ERK2 were compared in extracts from BRY- and LC/BRY-treated cells (Figure8A). BRY induced maximal ERK phosphorylation within 1 hour of treatment, after which expression rapidly declined to basal levels by 4 hours. In marked contrast, cells exposed to BRY in conjunction with LC exhibited pronounced expression of phosphorylated ERK throughout the 8-hour treatment interval, and continued to display elevated phospho-ERK expression for as long as 12 hours (data not shown). Total ERK expression was unaltered by treatment with BRY or the LC/BRY combination (Figure 8A); moreover, 1 μM LC alone did not induce ERK phosphorylation nor did it alter ERK expression (data not shown).

LC/BRY-treated cells exhibit sustained MAPK activation and MEK inhibitors oppose mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in cells treated with these agents.

(A) U937 cells were exposed to either BRY or LC/BRY for the indicated intervals and analyzed for the presence of phosphorylated ERK expression as described in “Materials and methods.” (B,C) Cells were pretreated with the designated MEK inhibitors (PD98059 [●], U0126 [○], SL327 [▪]) for 1 hour before the addition of LC/BRY. Following a 24-hour exposure, the cells were either (B) assayed for loss of mitochondrial membrane permeability by determining the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6; values are expressed as the percentage inhibition of LC/BRY-mediated mitochondrial damage compared to cells that were not exposed to MEK inhibitors or (C) the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by morphologic analysis as above. In each case, values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

LC/BRY-treated cells exhibit sustained MAPK activation and MEK inhibitors oppose mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in cells treated with these agents.

(A) U937 cells were exposed to either BRY or LC/BRY for the indicated intervals and analyzed for the presence of phosphorylated ERK expression as described in “Materials and methods.” (B,C) Cells were pretreated with the designated MEK inhibitors (PD98059 [●], U0126 [○], SL327 [▪]) for 1 hour before the addition of LC/BRY. Following a 24-hour exposure, the cells were either (B) assayed for loss of mitochondrial membrane permeability by determining the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6; values are expressed as the percentage inhibition of LC/BRY-mediated mitochondrial damage compared to cells that were not exposed to MEK inhibitors or (C) the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by morphologic analysis as above. In each case, values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

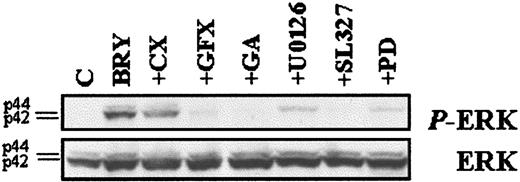

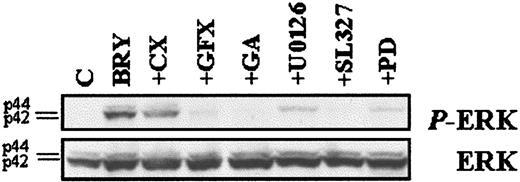

To investigate the functional significance of MAPK activation in potentiation of LC-mediated apoptosis by BRY, the specific MEK inhibitors, PD98059,51 U0126,52 and SL32753 were used. The data in Figure 8B demonstrate that MEK inhibitors partially blocked loss of ΔΨminduced by the LC/BRY combination treatment in a dose-dependent manner. It should be noted that high concentrations (eg, > 33 μM) of the MEK inhibitors induced apoptosis themselves (not shown). The ability of BRY to potentiate LC-induced apoptosis was also attenuated in a dose-dependent manner by each of the MEK inhibitors, and results generally paralleled antagonism of mitochondrial discharge (Figure 8C). MEK inhibition did not, however, modify cell death induced by LC or BRY alone (not shown). To confirm that MEK inhibitors were in fact blocking MAPK activation, phospho-ERK expression was monitored in extracts from cells exposed to the various inhibitors followed by a 30-minute exposure to BRY (Figure 9) or LC ± BRY (data not shown). In all instances there was a marked decrease in phospho-ERK expression. The MEK inhibitors (33 μM each) reduced ERK phosphorylation by similar degrees in both BRY- and LC/BRY-treated cells (eg, for BRY: PD-50%, U0126-70%, SL327-86%; for LC/BRY: PD-43%, U0126-76%, SL327-83%, n = 3). Significantly, other agents that attenuated LC/BRY-mediated apoptosis (eg, GFX and geldanamycin) also attenuated phospho-ERK expression. These findings demonstrate that BRY-induced MAPK activation is prolonged in LC-treated U937 cells and also provide functional evidence of a role for sustained MAPK activation in potentiation of LC-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death by BRY.

MEK inhibitors block ERK phosphorylation.

U937 cells were pretreated with the indicated inhibitors, as described previously, before incubation with BRY (10 nM; 30 minutes). (Top) Western blot illustrating the levels of phosphorylated ERK using the phosphorylated p44/p42 MAPK-specific antibody. (Bottom) Western blot with MAPK antibody confirming equal loading and transfer of proteins.

MEK inhibitors block ERK phosphorylation.

U937 cells were pretreated with the indicated inhibitors, as described previously, before incubation with BRY (10 nM; 30 minutes). (Top) Western blot illustrating the levels of phosphorylated ERK using the phosphorylated p44/p42 MAPK-specific antibody. (Bottom) Western blot with MAPK antibody confirming equal loading and transfer of proteins.

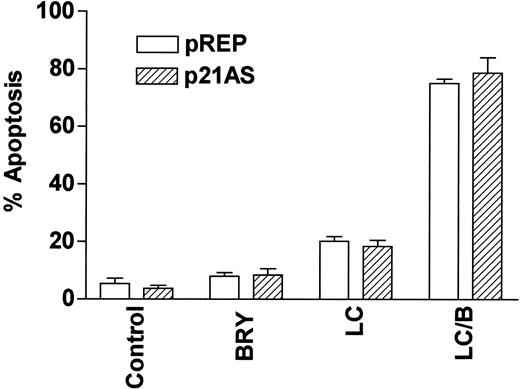

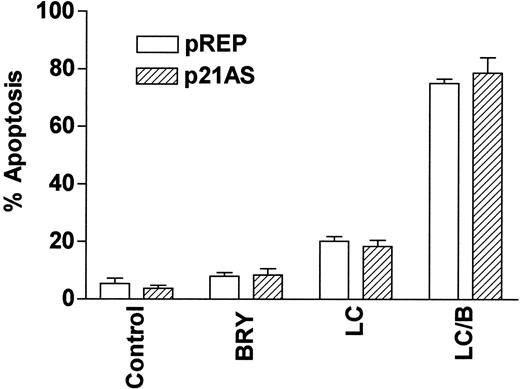

LC/BRY-mediated apoptosis does not involve the MAPK downstream target p21CIP1

Finally, we have previously reported that dysregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CIP1, a downstream target of MAPK,54 modifies the susceptibility of U937 cells to apoptosis induced by the cytotoxic agent 1-β-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine (ara-C).55 To determine whether p21CIP1 might be involved in potentiation of LC-mediated apoptosis by BRY, stable p21CIP1antisense-expressing cells (p21AS) and their vector control counterparts (pREP4) were exposed to BRY and LC alone and in combination (Figure 10). In marked contrast to results obtained with ara-C,55 dysregulation of p21CIP1 did not lead to a statistically significant increase in LC/BRY-mediated apoptosis, nor in apoptosis induced by LC alone. This finding indicates that apoptosis induced by LC/BRY treatment, in contrast to that induced by the antimetabolite ara-C, proceeds through a pathway that is independent of the MAPK downstream target, p21CIP1.

The CDKI p21WAF1/CIP1 is not involved in LC/BRY-induced cell death.

A stable U937 cell line expressing an antisense p21WAF1/CIP1 construct (p21AS) or its empty vector control (pREP) was exposed to BRY (10 nM), LC (1 μM), or LC/B for 24 hours, after which apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

The CDKI p21WAF1/CIP1 is not involved in LC/BRY-induced cell death.

A stable U937 cell line expressing an antisense p21WAF1/CIP1 construct (p21AS) or its empty vector control (pREP) was exposed to BRY (10 nM), LC (1 μM), or LC/B for 24 hours, after which apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).

Discussion

The results described herein suggest the mechanism by which the PKC modulator BRY 1 enhances cell death in U937 human leukemia cells exposed to the proteasome inhibitor LC involves perturbations in the MAPK signaling cascade. Potentiation of cell death was documented by an increase in morphologic characteristics of apoptosis (ie, cell shrinkage, nuclear condensation, formation of apoptotic bodies), augmented DNA fragmentation (manifested by TUNEL positivity), and an increase in the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6, reflecting loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm). Enhanced cleavage of the proform of caspase-3 was also noted in LC/BRY-treated cell extracts, as well as degradation of one of its principal downstream substrates, PARP. This response was cycloheximide sensitive indicating that up-regulation of short-lived proteins may be critical for LC/B-induced cell death. Taken together, these findings raise the possibility that coexposure of U937 cells to LC and BRY stimulates the synthesis of an as yet to be identified protein(s) that triggers the apoptotic cascade. Lastly, the ability of L-NAC to block LC/BRY-induced lethality is similar to results recently described by Mansat-de Mas et al, who found that 10 mM NAC opposed daunorubicin-induced apoptosis in U937 cells.56 These observations suggest that the mechanism underlying LC/BRY-induced lethality, as well as that associated with the administration of certain cytotoxic drugs, involves the generation of reactive oxygen species.

The ubiquitin/proteasome pathway represents the primary mechanism by which the bulk (eg, 80%-90%) of cellular proteins in proliferating cells are degraded. Numerous proteins are targeted for degradation by this pathway including (1) cell cycle proteins (eg, mitotic and G1 cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors), (2) oncogenic transcription factors (eg, c-Myc, c-Myb, p53), and (3) early response transcription factors (eg, c-Jun, c-Fos, IκB, NFκB-p105 subunit), reviewed by Lee and Goldberg.57 By regulating proteolysis, and thus intracellular protein levels, the proteasome plays a essential role in cell growth and apoptosis. LC is a natural product originally derived from Streptomyces58that, following conversion to its derivative β-lactone, binds irreversibly to the 20S-β subunit of the proteasome,27and is among the most selective of the proteasome inhibitors. Here, it inhibits chymotrypic-like, trypic-like, and caspase-like activities, without inhibiting the proteases trypsin, chymothrypsin, papain, calpain I, calpain II, cathepsin B,27 or lysosomal degradation.59 Proteasome inhibitors have attracted recent attention as potential antitumor agents because they induce apoptosis in proliferating cells23,24,35 and in topoisomerase II-resistant solid tumors60 but not in differentiated cells where they oppose cell death.36,37 Recently, a highly potent boronate inhibitor of the proteasome (PS-341), identified through a National Cancer Institute in vitro screen,61 has shown in vivo antitumor activity in murine xenograft models and is currently under clinical evaluation.

Currently, the mechanism by which proteasome inhibitors induce apoptosis is poorly understood, and relatively little information is available concerning the relationship between their actions and activation of signal transduction pathways, particularly the PKC/Raf/MEK/EPK cascade. However, evidence for cross-talk between this pathway and LC-related actions have recently emerged from studies involving the macrocyclic lactone, BRY.26 The most characteristic function of BRY lies in its ability to modulate PKC; that is, acute exposure induces PKC activation, whereas chronic exposure results in down-regulation.32,62,63 In this context, it is noteworthy that 2 other agents known to trigger initial activation and, on chronic exposure, down-regulation of PKC (eg, PMA and MEZ64,65) also enhanced apoptosis in LC-treated cells, although not to the same extent as BRY. It is conceivable that such differences reflect disparate effects on PKC isoform expression,14 or possibly the extent of PKC down-regulation. In marked contrast, PLC, a physiologic PKC modifier that activates but does not down-regulate PKC,66 did not potentiate cell death, but instead protected the cells from LC-induced apoptosis. This observation is consistent with evidence of an antiapoptotic role for chronic PKC activation.67Collectively, these findings are consistent with the concept that down-regulation of PKC contributes to the enhanced cell death observed in cells exposed to LC/BRY.

Although PKC down-regulation (eg, by PMA or BRY) has been implicated in the induction of apoptosis,67,68 it remained possible that the initial activation of PKC by BRY (or other PKC activators) contributed to promotion of LC-mediated cell death. The ability of the specific PKC inhibitor bisindoylmaleimide I (GF109203X) to attenuate the lethal actions of LC/BRY strongly suggests that this is the case. In addition, the finding that increasing the interval prior to GFX administration led to a progressive decline in cytoprotection indicates that early events (eg, those occurring within the initial 4-6 hours) following PKC activation are responsible for the enhanced lethality of the LC/BRY combination. It is important to note that Lee and coworkers have shown that the ability of BRY to down-regulate PKC in renal epithelial cells and nonimmortalized human fibroblasts stemmed from PKC dephosphorylation, ubiquitination, and targeting for proteasomal degradation.15,42,63 However, in contrast to the results of these studies, in which considerably higher LC concentrations were used (eg, > 50 μM), LC, when administered to U937 cells at low concentration (eg, 1 μM), failed to block BRY-induced PKC down-regulation at 24 hours. Although such a discrepancy may reflect dose- or cell type-specific differences, the present findings demonstrate that chronic activation of PKC by BRY is not required for enhanced lethality of the LC/BRY combination. In addition, the possibilities that LC interferes with degradation of alternative, as yet to be identified proapoptotic proteins in BRY-treated cells, or that LC-related cell death involves actions other than proteasome inhibition, cannot be excluded. In this regard, the relatively early onset of enhanced cell death in LC/BRY-treated cells, and our failure to detect changes in levels of expression or alterations in gel mobility of apoptotic regulatory proteins over this interval (eg, Bcl-2 and Bax; J.A.V. et al, unpublished observations) would argue against a primary role for such events in mediating lethality. However, the possibility that these agents induce subtle qualitative changes in Bcl-2 phosphorylation status that might influence the susceptibility of cells to apoptosis69 cannot presently be excluded.

Bryostatin has been shown to activate Raf through PKC-dependent phosphorylation of S497 and S619 (single-letter amino acid codes) residues.47 Consistent with a report demonstrating that depletion of Raf (eg, by geldanamycin) attenuates paclitaxel-mediated apoptosis,70 the presence of Raf was found to be required for enhanced apoptosis in LC/BRY-treated cells. In addition, BRY, which activates MAPK through the PKC/Raf/MEK pathway, transiently induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, whereas this effect was markedly prolonged in cells coexposed to LC. Significantly, each of the 3 specific MEK inhibitors examined (eg, PD98059, U0126, and SL327) inhibited both ERK phosphorylation and LC/BRY-induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner. MAPK activation was also essential for induction of the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition observed in LC/B-treated cells. Although activation of the MAPK cascade has generally been associated with antiapoptotic action,6,71it has recently been shown that MAPK activation may, under some circumstances, promote cell death.72 Taken in conjunction with the preceding results, such findings strongly suggest that dysregulation of the MAPK signaling pathway, either upstream at the level of PKC or Raf, or further downstream at the level of MEK, plays a key functional role in the enhanced apoptosis accompanying LC/BRY treatment of U937 cells.

Activation of JNK/SAPK has been shown to be critical for apoptosis induced by numerous environmental stresses, including proteasomal inhibitors such as MG132.42,73-75 However, in contrast to evidence suggesting a requirement for JNK activation in MG 132-induced apoptosis in U937 and 293 human kidney cells,42 a functional role for the SAPK pathway in the LC/BRY-mediated apoptosis of U937 cells could not be demonstrated. More specifically, our results indicated that (1) JNK activation was not enhanced following LC/BRY treatment; (2) LC/BRY-induced apoptosis was not inhibited by a dominant-interfering form of c-JUN (TAM67) or by pretreatment with curcumin, a pharmacologic inhibitor of the AP-1 pathway; and (3) LC/BRY-induced apoptosis was not inhibited by the specific p38 inhibitor, SB203580. Exposure to LC did induce HSP72 as reported previously in the case of MG13242; however, coexposure to BRY did not alter HSP72 expression. Thus, in the U937 cell system, c-Jun/AP-1 or p38/RK signaling does not appear to be involved in LC/BRY-induced cell death. In marked contrast, ceramide and TNF-mediated apoptosis is critically dependent on an intact c-Jun/AP-1 axis in these cells,75 indicating that LC/BRY-mediated apoptosis proceeds through a ceramide-independent pathway.

The recent observation that the proteasome inhibitor MG132 potentiates sodium butyrate-induced apoptosis and caspase activation in Y79 human retinoblastoma cells76 has potential relevance for the present study. In the Y79 system, dysregulation of the transcription factors p53, N-myc, and IκBα were implicated in enhanced cell death. It is noteworthy that sodium butyrate shares several features with bryostatin, including the ability to activate PKC77and to induce ERK phosphorylation.78 Although the specific role of PKC/MAPK signaling was not examined in the latter report,76 it is tempting to speculate that perturbations in the PKC/Raf/ERK cascade might represent a common mechanism underlying enhanced apoptosis in cells exposed to PKC activators in conjunction with proteasome inhibitors.

In summary, the present findings demonstrate that the combination of a proteasome inhibitor (LC) with BRY or other agents that perturb a putatively cytoprotective signaling pathway (eg, PKC/Raf/EPK) potently induce apoptosis in U937 human leukemia cells. More specifically, they suggest that initial activation and subsequent down-regulation of PKC, as well as sustained activation of MAPK, contribute to the increased susceptibility of these cells to LC-mediated lethality. Although the downstream targets of MAPK responsible for this phenomenon remain to be identified, the results of this study, particularly those shown in Figure 10, argue against the involvement of p21CIP1. An alternative MAPK target is NFκB, which has been implicated in both protection from79 as well as promotion of apoptosis,80 depending on the stimulus and model system. To address this issue, studies investigating the possible role of NFκB activation in LC/BRY-mediated cell death using an IκBα mutant81 are currently underway. In any case, a better understanding of the mechanism(s) by which agents that modulate the PKC/Raf-1/EPK cascade interact synergistically with proteasome inhibitors such as LC to induce leukemic cell apoptosis could ultimately have therapeutic implications.

The assistance of Dr Paul Dent, Department of Radiation Oncology, Medical College of Virginia, who made U0126 and SL327 available for these studies, is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Lora Kramer and Aida Saunders for their technical assistance, Dr M. Birrer for the U937/TAM67 cells, and Dr Z. Wang for the U937/p21AS cells.

Supported by awards CA63753, CA72955, and CA77141 from the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Julie A. Vrana, Dartmouth Medical School, Department of Pharmacology/Toxicology, Hinman Box 7650, Hanover, NH 03755.

![Fig. 4. The SAPK cascade is not involved in LC/BRY-induced apoptosis. / (A,B) U937 cell lines expressing a dominant negative construct of c-Jun (TAM67: clone 1-1 [left-hatched bar], clone 2-2 [cross-hatched bar]), and their empty vector controls (open bar) were exposed to either vehicle, bryostatin (B; 10 nM), lactacystin (LC; 1 μM) or the combination lactacystin plus bryostatin (LC/B) for 24 hours. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments and are (A) expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells determined by morphologic analysis or (B) loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, expressed as the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6 uptake. (C) U937 cells were pretreated with the specific p38/RK inhibitor SB203580 (SB; 10 or 20 μM) 30 minutes prior to the addition of LC plus BRY (LC/B). Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/97/7/10.1182_blood.v97.7.2105/6/m_h80710867004.jpeg?Expires=1765006871&Signature=B4Fv5a6BIDnmaEftOUV04HDnH5N37jLwTJ8zx5NN23alD-D1g3~Q1nrP68MyQ2KuFg2HkWvhSqW0quf2Uu6svACEiIJIxfJeuLgd5DukHsiGuIDiheHnCh8ldhQ0NmM0rdc8a-xQcCKL9UX1HKgnp3p3fl5HjN6df1EfLCC2ROqxLenkk9HmvPU71N0QajZIO6o9yo-QlDdd0ZgDJ7IouUz-JB6zMpIjGUNHVncx9MtYhrm6tXCjFQM8Z-GHDbQ21MVho8~Dj6fA3LynxbV~vC15u6pTI1JItF-uLpSC2vRdoYRCStyilcldxbFrV-pFN1i3OsVbX5xucxLyOZv2wg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. The ability of BRY to potentiate LC-induced apoptosis is PKC dependent. / (A) U937 cells were either pretreated or posttreated with the specific PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (GF109203X; 1 μM), as indicated. Cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation at 24 hours and the extent of apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis. [o] indicates the extent of cell death observed in cells treated with LC alone and [*] indicates the extent observed in LC/B-treated cells. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (B) U937 cells were exposed to either media (C), BRY (10 nM) (B), LC (1 μM) or the LC/BRY combination (LC/B) for 24 hours. The amount of phorbol-activated PKC activity remaining was then determined. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (C) Western blots of PKC isoform expression (PKCα, PKCβI, and PKCβII) at the indicated intervals following drug exposure.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/97/7/10.1182_blood.v97.7.2105/6/m_h80710867006.jpeg?Expires=1765006871&Signature=AizILNjIcxwpTAFPN0FWQV~9X6rO62FHAlwimSO7e7UGzNOoqOFzrBAgIxisqcafkZPf47FLZpULotWT6sP5YixVmuEuxzMzkfJK5HmZvedDDxvx-m-IJj1zsGC1ufxh1jIO8p4yoGBWzd0b638Dut0YF6RxizvWzEQ6w2qovxPrYyH3RNDa4RGPLw6~Np0bQK2jgp~DzQP2~ZdEXI-G2MERfwDe2pZ5NU10S1vJS4OuH4orxYcGes4ZULKexz55QcoKUViiVi3iWfJcETF5MFgXfctNyROlerIcritbEbyW6Lcip0EBJAKdU4eq6LEd9S2sXk~P0NY5JvrxUbM-uw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 8. LC/BRY-treated cells exhibit sustained MAPK activation and MEK inhibitors oppose mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in cells treated with these agents. / (A) U937 cells were exposed to either BRY or LC/BRY for the indicated intervals and analyzed for the presence of phosphorylated ERK expression as described in “Materials and methods.” (B,C) Cells were pretreated with the designated MEK inhibitors (PD98059 [●], U0126 [○], SL327 [▪]) for 1 hour before the addition of LC/BRY. Following a 24-hour exposure, the cells were either (B) assayed for loss of mitochondrial membrane permeability by determining the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6; values are expressed as the percentage inhibition of LC/BRY-mediated mitochondrial damage compared to cells that were not exposed to MEK inhibitors or (C) the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by morphologic analysis as above. In each case, values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/97/7/10.1182_blood.v97.7.2105/6/m_h80710867008.jpeg?Expires=1765006871&Signature=S~LqcVMR-cRoUoXuETkYl9iNJmUbGpuzl5R9x6DYT~AIOaP39wT5huLPG6uC1eC~sfR7zZQyZEijb0MaYSszU~xKN~1f4gjSRYAdJYz3OJfdqgbPhVvIndqM847J8xpaTxcuWykvvs-cMghP2DBm~YDzalt0NKrmF2nnZOj93OJrM71KqA3ZeGGLzPV-VW9~QEBx9MQl~I-2tXJ8amNZD1Fg310J6G03~jkF-iHmaPMW1ye5sivGwQjHswW9zLqA9iMOK2FqYjaxsVGRoyOdrDop4RB71ntPR5FjhoTv~rJIz3daHwImfcxToZcn4nIwcl6tlxQ6dSdgt0ly4C5Qyw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. The SAPK cascade is not involved in LC/BRY-induced apoptosis. / (A,B) U937 cell lines expressing a dominant negative construct of c-Jun (TAM67: clone 1-1 [left-hatched bar], clone 2-2 [cross-hatched bar]), and their empty vector controls (open bar) were exposed to either vehicle, bryostatin (B; 10 nM), lactacystin (LC; 1 μM) or the combination lactacystin plus bryostatin (LC/B) for 24 hours. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments and are (A) expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells determined by morphologic analysis or (B) loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, expressed as the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6 uptake. (C) U937 cells were pretreated with the specific p38/RK inhibitor SB203580 (SB; 10 or 20 μM) 30 minutes prior to the addition of LC plus BRY (LC/B). Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/97/7/10.1182_blood.v97.7.2105/6/m_h80710867004.jpeg?Expires=1765006872&Signature=eSF8jpLZnk1WCumibCdWXu7d8cYEt~smfJbc~DU4XGLpEA6RKlzOfEetKSV6a2OCjBk3myarBN1x60YQNP8Iah1jx8GqASL1k9HtJl8pbPvniEw93zfLenGNp5dliNAz7PcQPqd7o-wMZXrf7dXrCHqOW43I8gWVTDXZnRh2yQ8FId7yXeMDqQQwl576NPA3i26h~BA~Z5Rk3JyIWPiO2r0O~ewBR5-xGhc1MWFj~d24SUMGKwWU-PSwnXAoAS7cMNqCBYc4K9WtyoOF96al6AWVWskfIuyAwEnsQsoxUG9JPcNO7TGZxA2reAtrTfhUcjGs3StEKTUTwqbgt03BRw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. The ability of BRY to potentiate LC-induced apoptosis is PKC dependent. / (A) U937 cells were either pretreated or posttreated with the specific PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (GF109203X; 1 μM), as indicated. Cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation at 24 hours and the extent of apoptosis was determined by morphologic analysis. [o] indicates the extent of cell death observed in cells treated with LC alone and [*] indicates the extent observed in LC/B-treated cells. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (B) U937 cells were exposed to either media (C), BRY (10 nM) (B), LC (1 μM) or the LC/BRY combination (LC/B) for 24 hours. The amount of phorbol-activated PKC activity remaining was then determined. Values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM). (C) Western blots of PKC isoform expression (PKCα, PKCβI, and PKCβII) at the indicated intervals following drug exposure.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/97/7/10.1182_blood.v97.7.2105/6/m_h80710867006.jpeg?Expires=1765006872&Signature=xvPA5UwjuYRaYWsLCfiPeHUh-vaot5HeXYTkMUIPsO9LdtEV2SzR4siAOSCfm4tkcbVf0fCJq~dPXpoBIXTJRo0Lhu6QBRizZRKXZv9evWBBASB4H9mxezXNmaXYPoAQv24nv4dB9FH07464w97vOpn7b5-6AHpCQwSBelKvV1G4R-0IAKqPKpXsdCrAcFtLxls1VqRteFhyLc2fwbaPtHRgOzf-olt2MpoHwJexHT56DwdOtX5k8uK5BfBwRgVNBY1cgYO5bMANzOobBEmmJxe7BMRcZ48F6pJp8ya0Y2DDJ6A44S42hjFuOsU899aBTRDDjqpYlUJnpoiy3dPpQw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 8. LC/BRY-treated cells exhibit sustained MAPK activation and MEK inhibitors oppose mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in cells treated with these agents. / (A) U937 cells were exposed to either BRY or LC/BRY for the indicated intervals and analyzed for the presence of phosphorylated ERK expression as described in “Materials and methods.” (B,C) Cells were pretreated with the designated MEK inhibitors (PD98059 [●], U0126 [○], SL327 [▪]) for 1 hour before the addition of LC/BRY. Following a 24-hour exposure, the cells were either (B) assayed for loss of mitochondrial membrane permeability by determining the percentage of cells exhibiting low levels of DiOC6; values are expressed as the percentage inhibition of LC/BRY-mediated mitochondrial damage compared to cells that were not exposed to MEK inhibitors or (C) the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by morphologic analysis as above. In each case, values represent the means for triplicate experiments (± SEM).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/97/7/10.1182_blood.v97.7.2105/6/m_h80710867008.jpeg?Expires=1765006872&Signature=Al6R32ZUA~6CxUNDxNP1iiQ4lL5rDr3nEJ9fTf6ZrrtDwLDnmiODEObLsiw1j3nf8D8IgAqAjDGmZqaVva1b8af4LxqJrBt9CxkBVq7BdNfvQljJnJwq868qLvdZLqo~H~QhtByf0Wd4S5QNIdPHY9sIaUCVU3Oin~E74FhKIcoVZ4kLoQieVwFXrVcfBuoicNRM5YqCchiptjLch~XLXZZq5ImXGf9j~cBjHLXbuTB~D8XMaBAq~ksXgxNiJHpBkYsaMM4nU4eYt-f0NsigPOR1ur9x9JwUuxUCoG9pQcZNeovbaJ-zKlhMPppvmgLPd3DtsR~efDhFuwX6McqnvQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)