In this issue of Blood, Yeung et al1 report high molecular response rates and good tolerability of the first-in-class allosteric BCR::ABL1 inhibitor asciminib in a single-arm phase 2 study of 101 patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CP-CML), thereby bolstering the case for asciminib as a first-line treatment option.

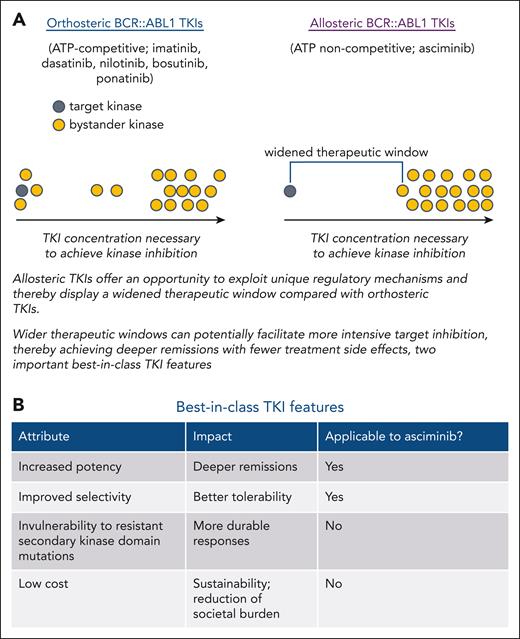

Prior development of 5 effective targeted therapies for patients with CP-CML has dramatically improved treatment outcomes. The 3 second-generation (2G) BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; dasatinib, nilotinib, bosutinib) have each shown superior milestone response achievement relative to the first-generation TKI imatinib, although differences in overall survival have not been observed, presumably due to the activity of 2G TKIs as salvage therapies.2-4 These higher response rates have been ascribed to greater potency of BCR::ABL1 kinase inhibition and are of importance to achieving deep molecular responses, which can facilitate treatment discontinuation attempts. However, most patients with CP-CML currently require indefinite TKI therapy. The 2G TKIs are generally associated with fewer day-to-day toxicities than imatinib, although they are associated with an increased risk of vaso-occlusive events and select additional toxicities. Their potency enables dose reduction in many responding cases that can improve the safety profile while maintaining response. In many patients with CP-CML, a treatment dose can be identified that achieves an acceptable response and maintains quality of life. However, a substantial proportion of patients with CP-CML on TKI therapy continue to experience chronic bothersome toxicities such as fatigue, mental fog, musculoskeletal pain, and gastrointestinal issues. It has been assumed that many TKI-associated toxicities are consequences of inhibition of unintended "bystander" kinases, although it is possible that at least some are due to interactions with other poorly characterized molecules. Imatinib and the 2G TKIs, as well as the third-generation agent ponatinib, all target the highly conserved tyrosine kinase adenosine triphosphate–binding pocket. Consequently, although relatively selective, each of these TKIs inhibits several other kinases. In contrast, asciminib targets a distinct allosteric pocket that plays a role in the physiologic autoregulation of ABL1 kinase,5,6 which appears restricted to ABL1 and ABL2 kinases, providing an opportunity for a wider therapeutic window, potentially fewer side effects, and the possibility of achieving greater potency of kinase inhibition that could translate to deeper molecular responses.7 These represent 2 of the 4 features of a potential best-in-class agent (see figure).

The potential for allosteric inhibitors to achieve greater selectivity and tolerability due to widened therapeutic window and features of best-in-class TKIs. (A) List of approved orthosteric and allosteric BCR::ABL1 TKIs. Schematic depiction of how allosteric TKIs may achieve improved potency and a widened therapeutic window through more selective target kinase inhibition. (B) Table describing best-in-class features of TKIs.

The potential for allosteric inhibitors to achieve greater selectivity and tolerability due to widened therapeutic window and features of best-in-class TKIs. (A) List of approved orthosteric and allosteric BCR::ABL1 TKIs. Schematic depiction of how allosteric TKIs may achieve improved potency and a widened therapeutic window through more selective target kinase inhibition. (B) Table describing best-in-class features of TKIs.

In patients with CP-CML who have taken at least 2 prior TKIs, asciminib has previously demonstrated considerable activity with good tolerability, although a few problematic toxicities have been observed (hypertension, elevated blood lipase levels).8 Longer-term follow-up is not yet available, and the extent to which worrisome cardiovascular toxicities may be associated with this agent is not yet clear. To assess whether asciminib has the potential to achieve more potent BCR::ABL1 inhibition in a tolerable manner, Yeung and colleagues report achievement of an early molecular response at 3 months in 93% of patients and a deep molecular response at 12 and 24 months in 49% and 65% of patients, respectively. Although direct comparisons to 2G TKIs are not possible due to the study design, these results appear at least comparable to what would be expected with a 2G TKI. Similarly, the tolerability of asciminib appears quite good in this population, although as has been observed in a prior study, grade 3/4 lipase elevation occurred in 10% of patients treated with asciminib. Additionally, grade 3 hypertension was observed in 10% of cases, many (but not all) of whom had a prior history of hypertension. There is currently little evidence of vaso-occlusive events, although this issue will require several more years of follow-up before firm conclusions can be drawn. As with other frontline TKI studies, a higher than desirable rate of treatment discontinuation was reported (18% at 21 months) for a variety of reasons, including blast phase transformation in 1 case.

Another important best-in-class feature of TKIs is response durability, which is related in part to imperviousness to TKI-resistant point mutations in BCR::ABL1. Most loss of response to TKI therapy occurs within the first 2 to 3 years following treatment initiation. Although it was initially hoped that clinically problematic mutations for asciminib would be largely restricted to a small number of amino acid residues near its binding pocket, recent evidence suggests that a growing number of mutations, in some cases removed from the asciminib binding pocket, may confer clinical resistance to asciminib.9 Yeung and colleagues find evidence of both classes of mutations in 4% of patients, all of whom had loss of response. Longer follow-up is necessary to fully understand the mutational vulnerability spectrum of asciminib and the extent to which durability of response is consequently impacted.

The data by Yeung et al add further confidence to the efficacy and safety of asciminib described in a recently published article of asciminib in a randomized study against approved frontline therapies for patients with newly diagnosed CP-CML.10 In that study, as expected, asciminib was superior to imatinib at achieving molecular responses. However, asciminib was not shown to be statistically significantly superior to 2G TKIs, nor was the trial designed to formally assess this important comparison. Based on the collective data demonstrating activity and tolerability, it appears likely that regulatory agencies may soon grant asciminib accelerated approval for use in newly diagnosed CP-CML. Given the spiraling costs of TKIs and the impending patent expiration of dasatinib, clinicians may soon have to reckon with glaring societal cost discrepancies between therapies that appear largely equivalent. One can therefore envision that inexpensive 2G TKIs or imatinib may be preferred initial treatments in the near future, with asciminib and other more expensive options reserved for patients not meeting treatment milestones or with persistence of bothersome side effects despite TKI dose reduction. As effective targeted agents have been developed subsequently for several other malignancies, the field of CML treatment may provide a framework for addressing this important societal issue. Nonetheless, the data provided by Yeung et al clearly confirm the potential for allosteric TKIs to improve therapeutic windows and be highly efficacious and tolerable. The availability of another highly effective and well-tolerated treatment option is certainly welcome news for patients with CP-CML, particularly those anticipated to require lifelong treatment.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.P.S. has received funding from Bristol Myers Squibb Oncology for the conduct of clinical research.