In this issue of Blood, Böhm et al1 provide contemporary real-world data on the use of etoposide for frontline therapy for pediatric patients with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (pHLH). The improved outcomes reported in this study relative to the HLH-94 and HLH-2004 trials provide a new benchmark to which novel, and often more expensive, treatment regimens should be compared.

HLH is syndrome initiated by common infectious, autoimmune, or malignant triggers. Abnormal cytotoxic lymphocyte function results in an inability to clear the trigger, with subsequent pathologic hyperinflammation. Diagnosis is based on criteria established by the Histiocyte Society in 2004. It includes fulfillment of 5 of 8 clinical and laboratory parameters or presence of a family history or genetic mutation consistent with HLH.2 Historically, HLH has been divided into “primary” or “secondary” forms. Patients with inherited defects in genes regulating cytotoxicity or associated with inherited immunodeficiency or immune dysregulation syndromes are categorized as having pHLH. Patients who develop HLH in association with a strong immunologic stimulus but lacking known familial mutation are categorized as having secondary HLH. Irrespective of the category, failure to promptly initiate immune suppression is associated with high mortality rates. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is the only curative option for patients with pHLH, isolated central nervous system (CNS) HLH, or recurrent disease.

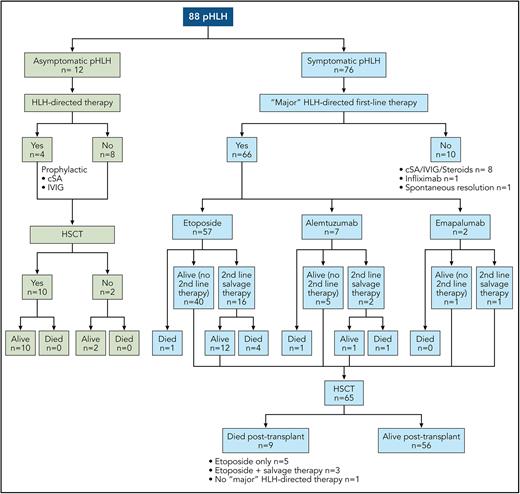

The current standard of care for pHLH, on the basis of the HLH-94 and HLH-2004 protocols, consists of dexamethasone- and etoposide-based therapy and results in a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 50% to 59%.2-4 Alternative approaches, including anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG),5 emapalumab (monoclonal antibody directed against interferon-gamma that the US Food and Drug Administration approved for refractory, recurrent, or progressive HLH),6 alemtuzumab (monoclonal antibody against CD52),7 and ruxolitinib (Janus kinase inhibitor),8 are being studied and used as frontline therapy. To better understand the efficacy and role of these novel agents, Böhm et al set out to provide more contemporary data on the real-world performance of etoposide as a frontline agent. The authors evaluated the diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of 88 patients with pHLH from 10 countries registered between 2016 and 2021 in the European Society of Immunodeficiencies and the Histiocyte Society registries. They describe the pretransplant and posttransplant course of 2 cohorts. The first included 76 symptomatic patients, of whom 71 (93%) fulfilled HLH-2004 criteria, 3 presented with isolated CNS-HLH, and 2 had CNS-HLH with partial systemic activity. The second cohort included 12 patients diagnosed before the onset of symptoms because of an affected sibling or, in the context of partial albinism, who remained asymptomatic until HSCT. A total of 66 (87%) patients with symptomatic pHLH received frontline therapy with a “major” HLH-directed drug, such as etoposide (57/66; 87%), alemtuzumab (7/66; 11%), or emapalumab (2/66; 3%). In contrast, 8 of the 12 asymptomatic patients received no HLH-directed treatment, whereas 4 received prophylactic cyclosporine and/or intravenous immunoglobulins until HSCT. HSCT was performed in 85% of the patients (65 symptomatic and 10 asymptomatic) (see figure). With a median time from disease onset to last follow-up of 5.39 years (range, 2.81-9.06 years), the overall 3-year probability of survival and event-free survival in this cohort of 88 patients was 81.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 72%-88%) and 75.8% (95% CI, 65%-84%), respectively.

Pre-HSCT and post-HSCT course of pHLH. cSA, cyclosporine; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Pre-HSCT and post-HSCT course of pHLH. cSA, cyclosporine; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

One of the findings of the study is that early HSCT of asymptomatic patients resulted in excellent survival (100%), emphasizing the potential benefit of newborn screening. The crucial finding is that contemporary outcomes of symptomatic pHLH are better than those reported in the HLH-94 and HLH-2004 studies, especially for patients receiving first-line therapy with etoposide. Ninety-one percent (52/57) of symptomatic patients who received first-line treatment with etoposide survived to HSCT, and 85% (44/52) of these patients survived post-HSCT, resulting in a 3-year OS of 77% (95% CI, 64%-86%). The pre-HSCT and OS rates were 73%/50% and 83%/59% in the HLH-94 and HLH-2004 studies, respectively. Salvage therapy was required in 28% (16/57) of patients with first-line etoposide but, unfortunately, did not result in increased complete remission (CR) rates or improved OS (only 56% of those who needed salvage therapy after etoposide survived) when compared with historical data.3,5 Perhaps earlier diagnosis, better supportive care, and shorter time to transplant (88 vs 148 days in HLH-2004), in addition to the use of improved salvage regimens, contributed to reduced disease reactivation rates, reduced pretransplant treatment toxicity, and improved outcomes.

Improved outcomes cannot be attributed solely to better disease control. Allogeneic HSCT approaches for HLH disorders have evolved considerably over time. Traditional fully myeloablative conditioning regimens, as used in the HLH-2004 study, were associated with high risks of toxicities and mortality. Recently, reduced-toxicity myeloablative and reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens have offered remarkably low rates of regimen-related toxicity and early mortality while still maintaining sustained engraftment.9 In this study, OS after HSCT was 88% for symptomatic patients (85% for etoposide first-line treatment), which compared favorably with historical data of HLH-94 (66%) and HLH-2004 (70%). Given the lack of significant improvement in pretransplant CR rates and the need for salvage therapy in ≈28% of patients receiving frontline etoposide, the improved survival is likely due to the reduced toxicity of myeloablative conditioning or RIC that most patients received and better supportive care in the patients who more recently underwent transplant.

The study's limitations include its retrospective nature and the fact that >70% of the patients were registered in Germany and Switzerland; thus, enhanced care at those sites is 1 possibility for improved outcomes. Although the data support improved outcomes in patients with pHLH, they are not powered to address the superiority of etoposide-based frontline therapy compared with ATG, alemtuzumab, and emapalumab, especially as the outcomes with etoposide and alternative agents were comparable. However, the data highlight the continued urgent need for clinical trials evaluating more active and cost-effective agents for upfront therapy and comparing the efficacy with the new standard provided by this article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.L.H. is on the advisory board of Swedish Orphan Biovitrum AB (SOBI). N.G. declares no competing financial interests.