The study by Ahn et al in this issue of Blood is an important clinical update with a 5-year follow-up on efficacy and toxicity of single-agent ibrutinib, an inhibitor of B-cell receptor (BCR) pathway–associated Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK), in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1

This study, in which the majority of patients are treatment-naive (TN), complements another 5-year follow-up study of (mostly) relapsed/refractory (RR) patients recently published in O'Brien .2

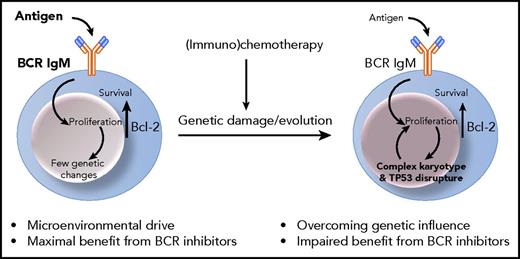

Signaling through the BCR, which is the key functional unit of all normal and tumor B cells, is a major critical component influencing behavior of CLL leukemic B cells.3 Signaling occurs following engagement of the BCR immunoglobulin M/D (IgM/D) complex by antigen likely at tissue sites. The levels and signaling capacity of surface IgM are modulated by antigen engagement,4 and associate with disease progression.5 A second component is the constitutive upregulation of bcl-2 protein. For CLL, increased expression involves the loss of BCL-2 gene negative regulators microRNAs (miRNAs) miR-15a and miR-16-1 in the 13q14.3 locus.6 Chronic antigen engagement would naturally lead to BCR anergy and death by apoptosis. However, the increased levels of bcl-2 in CLL protect the tumor cells from apoptosis thereby allowing surface IgM recovery in the circulation and, following reentry into tissue sites, antigen-driven proliferation.3 As proliferation occurs at those sites, genetic changes will accumulate and diversify within the tumor clone, with patterns varying among cases of CLL. Those involving TP53, either by deletion or mutation (TP53− CLL), are of obvious clinical importance, by causing more rapid progression and failure to respond to conventional (immuno)chemotherapy. Chemotherapy may cause further genetic damages, which will less likely be repaired in the context of TP53 disrupture, and which may eventually prevail over microenvironmental control at later stages (see figure).

Ibrutinib inhibits the activation of BTK by irreversibly binding cysteine 481 (C481) in the protein active site, thereby affecting not only BCR signaling, but also cell adhesion and migration, explaining the rapid and prolonged redistribution of CLL cells into the peripheral blood.7 Redistribution will eventually make the antigen-starved CLL cells metabolically inactive and ultimately bound for death, while kept in the circulation.

This phase 2, open-label, single-center, investigator-led study by Ahn et al confirms that continuous therapy with single-agent ibrutinib therapy is effective in keeping the CLL under control and is well tolerated in the majority of (but not all) patients with CLL.1 It documents that quality of response improves over the duration of treatment and that ∼28% of patients obtain a complete remission (CR) at 5 years of therapy with this BCR-associated signaling kinase inhibitor. The gradual improvement of responses confirms and extends the improving trends also observed in the phase 1b/2 multicenter PCYC-1102/1103 sponsor-led trial.2

Ahn et al also confirm the remarkably prolonged duration of responses and suggest that this is apparently irrespective of genetic subsets. They indicate that the overall response rate (ORR) and the CR rate are similar in patients with or without TP53 disrupture. The ORR and CR in TP53− CLL are 95% and 29%, respectively. These results apparently contrast with the 79% ORR and 6% CR of the TP53− CLL in the PCYC-1102/1103 trial.2 In the study by Ahn et al, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival also appear superior to the PCYC-1102/1103 study. One possible explanation for the differences is patient selection. In fact, the majority of patients with TP53− CLL recruited in the study by Ahn et al are TN (69%; RR, 31%). Instead, the large majority of TP53− CLL patients in the PCYC-1102/1103 trial (TN, 6%; RR, 94%) are relapsed or refractory to (immuno)chemotherapy combinations that have known mutagenic effect and may certainly favor generation of complex karyotypes and a more aggressive disease as a consequence. Although karyotype complexity was not investigated in the study by Ahn et al, both studies convey that treating patients with ibrutinib after chemotherapy is certainly less effective, whereas administration of ibrutinib in TN patients is expected to be highly successful with prolonged and durable (at least 5 years) responses in (almost) all TN patients.1,2

Conceivable with the increase of CR rates, Ahn et al also demonstrate that minimal residual disease (MRD) gradually decreases over time of treatment. Interestingly, patients with unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene (IGHV) appear to have significantly lower residual disease burden than those with mutated IGHV, although this difference does not yet seem to impact on PFS. If the different quality of response is confirmed, it will also be relevant to investigate whether this is consequent to the nature of the cell of origin or if it is actually reflecting the different IgM levels/signaling capacity, which is known to be different in the 2 subsets.5 It will also be important to investigate whether the different quality of response will have any impact on duration of responses in longer follow-ups.

However, the authors also highlight that only 25% of patients achieve a very low burden of disease (<10−2 CLL cells per leukocyte) and that undetectable MRD (<10−4) is unlikely to be achieved by single-agent ibrutinib. The inability of ibrutinib to eradicate disease might not necessarily be a limiting factor if therapy continued indefinitely and cells were prevented from tissue reentry. However, >40% of patients will experience treatment discontinuation, which in a large fraction is due to adverse events including infections. This update by Ahn et al does not specifically review the consequences of BTK inhibition on normal immune reconstitution. However, opportunistic infections have become a concern in the setting of prolonged therapy with ibrutinib and one would wonder whether prolonged BTK inhibition will eventually cause nontumor B-cell impairment similar to that of the genetic deficiency of children.8

If the goal is disease eradication, combined strategies may be a way forward. BCR signal inhibition may influence sensitivity to BH3 mimetics by preventing the induction of antiapoptotic proteins including Mcl-1,9 and ongoing trials investigating the consequences of the combination of BCR-associated kinase signal inhibitors with BH3 mimetics suggest very high and early response rates without causing significant toxicity.10 Certainly the study by Ahn et al confirms and extends previous observations that ibrutinib is highly effective in CLL. Although it is not sufficient to eradicate disease, ibrutinib targets a key pathogenetic pillar of CLL and provides a drug around which to structure novel chemotherapy-free strategies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.