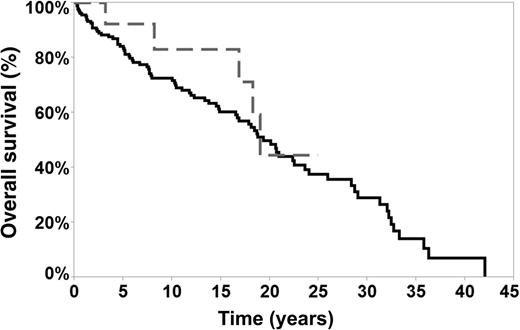

In this issue of Blood, Kenderian et al report a lower rate of transformation (7.6%) to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) for patients with nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) compared with other series and the lack of negative impact on overall survival (OS) (see figure).1

OS of transformed and nontransformed patients. The median OS in transformed patients was 18.8 years (grey line) vs 19 years in nontransformed patients (black line). See Figure 3 in the article by Kenderian et al that begins on page 1960.

OS of transformed and nontransformed patients. The median OS in transformed patients was 18.8 years (grey line) vs 19 years in nontransformed patients (black line). See Figure 3 in the article by Kenderian et al that begins on page 1960.

These conclusions come from a comprehensive analysis of the Mayo Clinic Lymphoma Database of 222 newly diagnosed NLPHL patients from 1970 to 2011 and represents one of the largest retrospective data reviews on this pertinent topic for patients with this rare hematologic malignancy. Unique within their data review are both the large number of patients followed and the long length of median follow-up at 16 years. Risk factors for transformation included use of any prior chemotherapy and splenic involvement. The 5-year OS for patients with transformation was not negatively impacted and remained high at 76.4%.

NLPHL is a very rare subtype of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) representing just 3% to 5% of all cases diagnosed. It is clinically divergent from the presentation of classical HL (cHL) in that it is often diagnosed at an older age during the third to fourth decades of life and tends to have a more indolent course with increased risk for late relapses and transformation.2 Given these clinical features, the diagnosis was initially thought to most closely overlap with follicular lymphoma and other indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas. However, Brune and colleagues demonstrated through gene expression profiling analysis that NLPHL most closely overlaps with T-cell–rich B-cell lymphoma (TCR-BCL), a subset of DLBCL, and cHL.3 The histologic variants of NLPHL as described by Fan et al were found to be associated with both higher rates of relapse and advanced stages of disease.4 In addition, the presence vs absence of these histologic variants forms a key component of the prognostic scoring model developed by the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG). In the GHSG model, 3 distinct risk factor groups were based on variant histopathologic growth pattern, low serum albumin, and male sex, which are incorporated into treatment selection criteria, moving beyond use of just stage alone.5

Prior to the current reports, one of the largest retrospective series was published by the British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA). Fourteen percent of 95 NLPHL patients followed experienced transformation to an aggressive BCL at a median of 8.1 years, with an actuarial risk of transformation at 20 years of 30%.6 The BCCA database review describes not only a higher rate of transformation but also a delayed time frame for these transformations by an increase of about 5 years when compared with the median time to transformation in the Kenderian et al article of 2.9 years. However, similar to the Mayo Clinic, the BCCA also described splenic involvement as a risk factor for transformation. Kenderian et al also described that past treatment with chemotherapy also increased risk of transformation potentially because patients believed to have higher risk disease were treated with chemotherapy.

Given the rarity of the diagnosis, the challenge that still remains is what is the optimal treatment of a patient who has a higher risk for disease transformation based on clinical or biologic features. In both the Mayo and BCCA articles, the majority of the patients who received chemotherapy for NLPHL before transformation were treated with ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) or ABVD-like regimens, and then at transformation many were treated with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) ± R (rituximab). Data from both centers thus raises the question of alternative regimens for patients with the highest risks for transformation. In support of this, the Princess Margaret group has described, for advanced-stage patients, a high relapse rate of over 50% at 5 years for NLPHL patients when treated with ABVD including 4 patients who developed transformation.7 Taken together, this suggests that, for patients identified as having high risk of transformation, alternative regimens beyond ABVD potentially be considered. The challenge though is identifying what that regimen should be. We at the MD Anderson Cancer Center have used a regimen based on R-CHOP and have not seen transformations. But only through large cooperative clinical trials can we determine whether R-CHOP or other more novel regimens are actually superior to ABVD or R-ABVD for patients at high risk of transformation.8

In conclusion, these data from Kenderian et al provide reassurances to clinicians who care for patients with NLPHL in that (1) even if transformation occurs it is generally at a low rate and (2) with additional treatment these patients do well with survival equal to their nontransformed NLPHL counterparts. Prospective multicenter clinical therapeutic trials, however, remain vital to continue to advance how we care for these patients with this very rare hematologic diagnosis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.