Abstract

This year we celebrate Blood's 70th year of publication. Created from the partnership of the book publisher Henry M. Stratton and the prominent hematologist Dr William Dameshek of Tufts School of Medicine, Blood has published many papers describing major advances in the science and clinical practice of hematology. Blood's founding antedated that of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) by more than 11 years and Stratton and Dameshek helped galvanize support for the creation of ASH. In this review, I place the birth of Blood in the context of the history of hematology before 1946, emphasizing the American experience from which it emerged, and focusing on research conducted during World War II. I also provide a few milestones along Blood's 70 years of publication, including: the growth in Blood's publications, the evolution of its appearance, the countries of submission of Blood papers, current subscriptions to Blood, and the evolution of topics reported in Blood's papers. The latter provides a snapshot of the evolution of hematology as a scientific and clinical discipline and the introduction of new technology to study blood and bone marrow. Detailed descriptions of the landmark discoveries reported in Blood will appear in later papers celebrating Blood's birthday authored by past Editors-in-Chief.

Introduction

Blood's 70th anniversary provides an opportunity to reflect on its extraordinary contributions to medical science; medical diagnosis, treatment, and prevention; and the evolution of the discipline of hematology. The brainchild of the hard driving and visionary medical book publisher Henry M. Stratton and the éminence grise Dr William Dameshek of Tufts School of Medicine, Blood became the first English-language hematology periodical when it began publication on January 1, 1946.1 In fact, Blood's birth antedated the creation of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) by more than 11 years.1,2 Blood was the midwife for ASH since Stratton also initiated the informal Blood Club at the 1954 Atlantic City meeting of the Association of American Physicians, the American Society for Clinical Investigation, and the American Federation for Clinical Research. He also brought together the 10 hematologists at the 1956 meeting of the International Society of Hematology in Boston that led to the creation of ASH at its organizational meeting, led by Dameshek, on April 7, 1957 at the Harvard Club in Boston. The first official ASH meeting was held in Atlantic City on April 26-27, 1958.2 In this review, I will try to place the birth of Blood in the context of the history of hematology before 1946, emphasizing the American experience from which it emerged, and provide a few milestones along its 70 years of publication. Detailed descriptions of the landmark discoveries reported in Blood will appear in later papers celebrating Blood's birthday authored by past Editors-in-Chief.

Hematology before Blood

Table 1 provides select highlights of the history of hematology before Blood. Many of the original papers describing 20th century advances, along with historical annotations and English translations, were compiled in a book by Lichtman et al.3 Wintrobe’s book, Blood, Pure and Eloquent provides a broad historical overview4 and a number of other sources provide valuable historical information on select topics.5-9

Overall landmarks

European investigators made nearly all of the landmark discoveries in hematology in the 19th century and Hewson in England, Hayem in France, and Ehrlich in Germany have all been called the father of hematology.4 Osler has been cited as the first “American” hematologist,10 despite his Canadian birth and education, because of his early use of the microscope to study blood cells and his bringing microcopy to the clinic at Johns Hopkins by creating a Division of Clinical Microscopy.11 He was among the first to describe blood platelets and to recognize their contribution to human thrombi.10,12,13 Osler’s landmark textbook, The Principles and Practice of Medicine, first published in 1892, provides a convenient window into the state of hematologic knowledge at that time. The section on diseases of the blood occupies just 24 of 1050 pages and is combined with the section on diseases of the ductless glands in one chapter. Anemia is divided into secondary and primary causes; the former include hemorrhage, Bright disease (renal insufficiency), inanition, and heavy metal toxins, whereas the latter includes the mysterious “chlorosis” (later recognized as due to iron-deficiency, but already being treated successfully with iron), and “idiopathic or progressive pernicious anemia” of unknown origin and associated with “large giant forms (of RBCs), megalocytes, which are often ovoid in form.” Leukemia is the second disorder described, with the description classic for chronic myelogenous leukemia, although a four-sentence description of “acute lymphatic leukemia” and a brief mention of other forms of white blood cell (WBC) abnormalities are also included. The third category of blood disease discussed is Hodgkin disease, with emphasis on the clinical and pathological features of the lymph node enlargement. Ironically, despite Osler’s earlier studies on platelets,11,14 they are not mentioned in the book, although a description of a disorder resembling immune thrombocytopenia is included under the term “purpura haemorrhagica” among the “constitutional diseases.” Hemophilia is also considered under the latter rubric and was recognized as being hereditary due to the fastidious genealogies recorded by American physicians, most particularly Otto of Philadelphia in 1803.15 Because the etiology was unknown, Osler speculated that it was due to a “peculiar frailty of the blood vessels or some peculiarity in the constitution of the blood.” His advice on the prevention of genetic transmission of hemophilia is direct, but jarring to modern sensibilities; “the daughters should not marry, as it is through them that the tendency is propagated.”

Ehrlich’s discovery of the benefits of blood cell staining with aniline dyes in 187716,17 led to an explosive growth in hematologic investigation, resulting in the production of numerous books and atlases of blood cell morphology in health and disease. In Boston, Cabot produced a major guide to examination of blood in 1898 and Wright optimized the stains to facilitate performing differential leukocyte counts, identified the megakaryocyte as the precursor of platelets based on staining properties (1906), and developed new supravital stains to identify reticulocytes.7,18-20 Herrick in Chicago went on to report the first case of sickle cell disease in 1910,21,22 and in 1925 Cooley and Lee in Detroit reported the anemia syndrome later named “thalassemia” by Whipple and Bradford in Rochester in 1932 (based on the Greek term for “sea”).23-25 The introduction of the sternal puncture to obtain bone marrow in 1929 by Arinkin26 in Germany made it much easier for hematologists to obtain specimens to correlate with peripheral blood smear findings, adding a crucial dimension to hematologic diagnosis and providing an enormous research advantage. Quantitation of red blood cells (RBCs) was achieved by the development of the hemocytometer and accurate pipettes for diluting blood samples, but reproducibility remained challenging well into the 20th century.7 The platelet was the last formed element of blood to be quantified because of its size,13 but by 1910 Duke in Boston was able to demonstrate a compelling correlation between clinical hemorrhage, a low platelet count, and a prolonged bleeding time based on puncturing the earlobe.27 Moreover, he showed that a whole blood transfusion raised the platelet count and immediately stanched the bleeding. Kaznelson, while a medical student in Germany in 1916, proposed splenectomy for immune thrombocytopenia and the first patient treated obtained a spectacular result.19,28 By 1938, US hematology matured to the point where Downey in Minneapolis could edit a 4 volume Handbook of Hematology containing 1448 illustrations and 50 color plates.29 Wintrobe’s first edition of his classic textbook Clinical Hematology was completed in Salt Lake City just before the United States entered World War II, and in many ways may be considered the beginning of the modern era of US hematology.10

The most dramatic and far reaching event in hematology in the United States in the pre-Blood period was Minot and Murphy’s 1926 report that feeding liver to patients with pernicious anemia could cure this otherwise fatal disorder.3,7,10,30,31 This dramatic breakthrough was an enormous stimulus to hematologic investigation. The next year, Minot succeeded Peabody (who previously was the Resident Physician in the Hospital of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research) as the Director of The Thorndike Memorial Library at Boston City Hospital, the first clinical research facility in a municipal hospital in the United States, complete with 17 beds for the study of selected patients, and supported in large part by the city of Boston. Among the many famous investigators recruited to the Thorndike was Dr William Castle, who played a vital role in the research leading to the discovery of intrinsic factor and vitamin B12 by a series of classic experiments in which he ingested 300 g of rare hamburger, extracted his own stomach contents 1 hour later, and 1 hour thereafter, administered the liquefied mixture to a pernicious anemia patient through a stomach tube.7,30,32 Building on the pioneering studies of reticulocytes by Smith in 1891 in New York,33 Vogel and McCurdy in New York in 1913,34 and Krumbhaar in Philadelphia in 1922,35 the patients’ response was measured by an increase in reticulocytes as measured by Wright’s supravital stain. Minot shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1934 and went on to play a crucial role in Blood’s history because he not only supported its creation but also recommended the name Blood, The Journal of Hematology.2

Brief histories of select topics in hematology

Coagulation and fibrinolysis.

Theories of blood coagulation go back at least to the Greeks, but Hewson in 1770 in London was the first to develop a method of separating plasma from the formed elements in blood using a trick known by those who made blood sausage that high concentrations of salt impeded coagulation.36 He went on to show that fibrin could form from the plasma alone, leading to the discovery of fibrinogen. By the late 1800s, studies by Buchanan in Scotland and Schmidt in Estonia led to a model in which an enzyme in serum, thrombin, could clot fibrinogen, and that thrombin must come from an inactive precursor, ie, prothrombin.15,37,38 Schmidt also recognized that tissues contained a factor that could activate prothrombin, leading to the classic theory proposed by Morawitz in 190539 in Germany, in which tissue thromboplastin activates prothrombin to thrombin, with the latter then clotting fibrinogen. Armand Quick, working in New York and later Milwaukee, took advantage of the new knowledge about tissue thromboplastin activating coagulation and devised the one-stage PT in 1935, not only opening a new era in coagulation research, but also providing a crucial clinical laboratory method to test patient’s plasma and to direct therapy.6,40 This set in motion the identification of the other coagulation factors, as patients with these disorders were identified and mixing studies elucidated the ability to correct the defects, as well as the development of additional assays and the delineation of the intrinsic pathway of blood coagulation.15 In 1936, Patek and Stetson in Boston showed that normal plasma could correct the clotting defect in hemophilic plasma, a major step forward in resolving the issue as to whether platelets or plasma was responsible for the bleeding.41,42 In parallel with these studies of coagulation, Dam in 1929 in Denmark found that cereals or seeds could correct the coagulation defect caused by feeding chicks an ether-extracted diet deficient in fat soluble vitamins.43 He termed the factor in the foods “Koagulations-Vitamin,” better known as vitamin K, and by the late 1930s the structure of vitamin K was identified and being used therapeutically to correct the bleeding diathesis in patients with obstructive jaundice.44,45 In related studies, Schofield in Canada in 192446 identified eating spoiled sweet clover as the cause of the bleeding disorder acquired by cattle, ultimately leading to Link’s discovery in Wisconsin of the toxic agent as bishydroxycoumarin (dicumarol)47 and the introduction of oral anticoagulants, most notably warfarin.48,49

Building on studies of Doyon in France on the anticoagulant released from the liver after treating dogs with “peptone,” in 1916 Jay McLean, a medical student working in Howell’s laboratory at Johns Hopkins, isolated a fraction from hepatic tissue that “showed a marked power to inhibit coagulation,” to which Howell gave the name heparin in 1918.50,51 The carbohydrate chemistry was complex and so the clinical use of heparin was delayed until the studies of Murray and Best in Canada and Crafoord and Jorpes in Sweden between 1936 and 1937.52-54 The recognition that heparin required a plasma cofactor for its full anticoagulant effect led to the identification of what was later called antithrombin III, and now just antithrombin.50,55

The lysis of blood clots was recognized in antiquity, and in 1893 Dastre in France gave the term “fibrinolysis” to the effect of serum in lysing fibrin.56 In 1933, Tillett and Garner in Baltimore identified a fibrinolysin in streptococcal lysates, and studies of the plasma cofactor required for this “streptokinase” activity led to its identification by Kaplan in North Carolina as plasminogen in 1944.57,58

Platelets.

Although several scientists probably described platelets earlier, Bizzozero’s detailed description from Italy of their role in both hemostasis and thrombosis using intravital microscopy in 1882 was a major landmark.59 Several qualitative platelet disorders were described before or soon after the birth of Blood, most notably, Eduard Glanzmann’s report of thrombasthenia in 1918 as a defect in platelet function, in particular, the ability to retract clots,60 a property of normal platelets first described in detail by Hayem in France.61 The platelet’s contribution to facilitating coagulation was discovered by Chargaff in New York in 193662 and expanded by Brinkhous in Chapel Hill in 1947.63 The vasoconstrictor activity of serum was linked to platelets independently by Hirose in Japan and by Janeway in Baltimore in 1918,64,65 but it would take ∼30 more years before Rapport in Cleveland identified the vasoconstrictor as serotonin66 and 7 more years for Zucker in New York to show that platelets contain serotonin and can release it when activated.67 In 1926, von Willebrand in Finland described the disorder that bears his name based on a detailed study of a very large family.68,69 He was able to identify a defect in platelet function rather than platelet count, and since females were affected, he demonstrated that inheritance differed from that of hemophilia, but he could only speculate as to whether the platelet function defect was intrinsic to the platelet or, as it turned out, due to a missing plasma factor.

WBCs (leukocytes).

In addition to his contributions to coagulation, Hewson also performed landmark studies of the lymphatic system, including delineating the anatomy and dual circulation of lymph nodes, noting the involution of the thymus with age, describing lymphocytes in lymph (chyle), and postulating that the lymphatics drained body cavities.36 WBCs were known to be present in pus by the early 19th century, but there was considerable controversy as to whether they came from circulating WBCs, especially since by that time there was evidence supporting a closed capillary system.71 Studies by William Addison in England (1843), Waller in England (1846), and Cohnheim in Germany (1867) established the ability of leukocytes to undergo diapedesis, thus leaving the circulation and entering inflamed or infected tissues.72-74 It was Metchnikov of Russia, using the transparent larval starfish as a model organism while working in Italy, who first recognized the phagocytic ability of leukocytes and went on to emphasize their role in protection from infection.75 Although this is taken for granted today, some early investigators proposed that WBCs exacerbated infections by giving organisms a place to grow inside the body.71 The clinical proof of the protective effect of granulocytes came from the report of a rapidly fatal case of agranulocytosis by Brown and Ophuls in San Francisco in 1902.76 The association of agranulocytosis in some cases with the drug aminopyrine was reported by Plum in Denmark in 1935,77 ushering in the recognition of drug-related blood dyscrasias.

Lymphocyte biology moved in parallel with studies of immunity, the latter culminating in the discovery of antibodies by von Behring and Kitasato in Germany in 1890 followed by Ehrlich’s elegant studies that led him to conclude that antibody forming cells have antibody on their surface.78-80 Landsteiner performed detailed studies of antigen recognition and later performed experiments that were a precursor to those of Medawar on cell-based immunity.80 Studies by Rich, Lewis, and Wintrobe in 1939 and Ehrich and Harris in 1942 strongly implicated the lymphocyte in antibody formation.80

Murphy in New York in 1926 provided important evidence that lymphocytes are important in preventing the growth of transplanted tumors and Haldane in 1933 in England summarized the evidence that a genetic locus (H-2) was important in determining whether a tumor would be rejected and proposed that it controlled an antigen.80 Thus, recognition of cell-based immunity grew out of both tumor immunology and Medawar’s war-time studies on skin transplantation immunology described later.

Blood transfusion.

The modern concepts of blood transfusion had to await the discovery of the circulation by Harvey in England in his 1628 landmark publication.81 Several xenotransfusions were performed on humans in the 1660s in England and France by Lower and Denis, respectively, primarily to improve the patients’ temperaments rather than to treat anemia.82 The results were spotty at best, resulting in classical symptoms of a transfusion reaction in one case, leading to death and a lawsuit. This stifled progress for about 150 years, until Blundell in London in 1817 started to perform animal studies and then extended them to human-to-human transfusions for treating obstetrical hemorrhage.83 Human artery to vein anastomoses were used for transfusions by Crile in Cleveland and Carrel in New York at the beginning of the 20th century.84,85 Although leech hirudin was used in 1914 to anticoagulate blood for transfusion,86 its anticoagulant effect was difficult to standardize. Defibrinated blood and rapid transfer systems of anticoagulated blood were also used with variable success.82 Building on Erhlich’s studies of hemolysis, Landsteiner’s landmark 1901 discovery in Austria of the A, B, and O (C) blood groups via isoagglutination reactions,87 which was later recognized with a Nobel Prize, opened up human blood transfusion and was put into practice by Ottenberg in New York between 1907 and 1908.82 Citrate anticoagulation for blood transfusion built on work from many investigators, but was placed on strong ground between 1914 and 1915 when Lewisohn88 in New York defined the toxic level of citrate and Rous and Turner89,90 in New York showed that red cells stored at 4°C in citrate-dextrose for 14 days functioned and survived normally in animal experiments.91 Robertson in Canada applied a similar approach to blood preservation and applied it to battlefield treatment during World War I.92 Landsteiner and Levine went on to identify the M, N, and P blood group antigens in 1927.93 Studies by Levine and Stetson in 1939 and Landsteiner and Wiener in 1940 in New York resulted in the identification of the Rh factor and its association with hemolytic disease of the fetus.94,95 Collectively, these advances made it possible to organize a hospital blood bank, the first of which has been credited to Fantus at Cook County Hospital in Chicago in 1937.82

Leukemia.

Both Bennett in Scotland and Virchow in Germany described cases of leukemia in 1845, each identifying a disease of 1 to 2 years in duration associated with enormous splenomegaly and dramatic changes in the blood.96-98 The disorder was ascribed to the mixture of pus with the blood by Bennett and to a dramatic increase in the colorless corpuscles (“white blood” or leukemia) by Virchow. Later, Virchow divided the leukemias into splenic and lymphatic types, depending on the organ most enlarged, and in 1889 Ebstein in Germany proposed the division into acute and chronic forms.96 The demonstration of the bone marrow as the source of leukocytes, first suggested by Neumann in Germany in 1870,99 and the introduction of blood cell staining by Ehrlich revolutionized the classification of the leukemias, with Naegeli in Switzerland describing the myeloblast.96 The first effective therapy of chronic leukemia (and lymphoma) was reported by Lissauer, a German physician, in 1865, and consisted of a 1% solution of arsenic trioxide (introduced by Fowler in 1786 as a general remedy for domestic animals and their owners).96,100 It produced temporary responses, including reductions in the size of the spleen and lymph nodes, decreases in leukocyte counts, and increases in RBCs. It remained in use until the discovery of x-rays by Roentgen in 1895 led to their medicinal use in malignancies by Pusey in 1902 in Chicago.101 Other forms of radiation treatment soon followed.96

The lymphatic system and lymphoma.

The milky fluid in lacteals in animals was noted by the Greeks and in 1651 Pecquet in France identified the cisterna chyli and thoracic duct.9 Bartholin in Denmark gave the lymphatics their name from the clear spring water appearance of lymph and established them as a separate system.9 The Italian physician and histologist Malpighi described lymph nodes and their accompanying lymphatic vessels circa 1687, along with the white pulp of the spleen.9 Hewson in 1771 was the first to observe cells in the lymph, leading to them being named “lymphocytes.”36,70 He also linked the function of the lymph nodes, spleen, and thymus.9,36,70

Hodgkin reported 7 cases from Guy’s Hospital, London, in 1832 of enlarged lymph nodes, accompanied in most cases by an enlarged spleen, that he thought were not due to tuberculosis or some other “irritation.”102 In 1856, Wilks, also of Guy’s Hospital, unaware of Hodgkin’s previous report, provided a more detailed analysis of a larger series of cases, including several previously published by Hodgkin himself!9,103,104 Greenfield in England published the first drawing of the typical giant cells found in Hodgkin disease in 1878105 ; Pel in the Netherlands and Ebstein in Germany described the typical fever pattern in 1885 and 1887, respectively9 ; and Sternberg in Vienna in 1898106 and Reed in Baltimore in 1902107 provided detailed histologic analysis, including descriptions of the typical multinucleate giant cell that bears their name.

Virchow in 1865 identified lymphosarcoma as a tumor of the lymph nodes108 and Kundrat109 in Germany in 1893 provided information on the progressive stages of the disorder. The variations in manifestations and the unfortunate introduction of the poorly defined term “pseudoleukemia” by Cohnheim made it difficult to precisely define and classify these disorders until the lymphocytes were subdivided based on their functional properties.

Hemolytic anemias.

Hemolytic anemias associated with hemoglobinuria produced a clinical picture that could be easily recognized and so these cases were reported in the 1800s, before clinical microscopy, including what were probably cases of paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria, march hemoglobinuria, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).110 Donath and Landsteiner in 1904 published the first of their studies that demonstrated the presence of an autolysin that attached to red cells in the cold and lysed them in conjunction with a labile serum factor when rewarmed.111 Chauffard in France in 1907 first reported the increased osmotic fragility of red cells in hereditary spherocytosis. Gull in England (1866) and Strübing in Germany (1882) provided important early descriptions of the syndrome of PNH, and in 1911 van den Bergh in The Netherlands reported that PNH patients' red cells underwent lysis in normal serum in the presence of carbon dioxide, concluding that serum contains a potentially lytic agent.110,112 In 1919, Ashby in England ingeniously developed a reliable method for measuring red cell survival by transfusing type O cells into type A recipients and noting the percentage of cells not agglutinated by anti-A sera.113 Her technique was crucial for differentiating “intrinsic” from “extrinsic” causes of hemolysis (and for optimizing the storage of blood for transfusion during World War II).110 Enneking in The Netherlands gave PNH its name in 1928,114 Ham in Boston developed the acidification assay for PNH that bears his name in 1937,115 and Dacie’s later studies in England of the red cell elimination curve in PNH indicated that PNH patients had both sensitive and insensitive red cell populations; he also reported that PNH could emerge after bone marrow aplasia.116

An ∼110- to 130-day lifespan of red cells in dogs was reported by Hawkins and Whipple in 1938 based on their monitoring a transient increase in biliary excretion of bile pigments after inducing hemolysis.117,118 The clinical syndrome of acquired hemolytic anemias was reported by Hayem in 1898 and Widal et al in France provided more detail in a series of papers starting in 1908.119 Understanding the immune basis of the disorder, however, had to await the development of the antiglobulin test by Coombs et al in England the year before Blood first started publication.120

Embryonic and fetal hematopoiesis and stem cell biology.

Weber and Kölliker in 1846 identified the liver as the major site of fetal hematopoiesis121 and later studies showed that blood islands in extra-embryonic tissues (area opaca and yolk sac) preceded the liver as the source of blood cells.122 In 1868, both Neumann in Germany123 and Bizzozero124 independently identified the bone marrow as the site of adult hematopoiesis. The intravascular origin of embryonic RBCs was described by van der Stricht in 1892, and supported by Dantschakoff and Maximow in Russia between 1907 and 1910.122

The staining techniques of blood smears developed by Ehrlich and refined by Pappenheim in Germany125,126 allowed for speculation on the maturation sequence of blood cell lineages, along with the cell(s) of origin. These two great investigators, however, came to different conclusions, with Ehrlich proposing a precursor marrow cell for the myeloid series and a lymphatic-derived precursor for lymphocytes, whereas Pappenheim proposed that the most primitive mononuclear cell he identified was the precursor of all blood cells.122 The latter view was independently put forward by Dantschakoff in 1908 and by Maximow, who emphasized the notion of the stem cell at the 1909 meeting of the German Haematologic Society in Berlin, one of the few meetings attended by many of the leaders in the field.122 The debate would continue, with the eminent Swiss hematologist Naegeli supporting the dual origin in 1900,127 and remained unresolved until the techniques of radiation biology provided the experimental tools to answer the question.

Hematology in World War II and its aftermath

The exigencies associated with World War II diverted the focus of many investigators, but provided resources for war-related research. Blood collection, preservation, and transfusion became very high priorities and the American Red Cross organized the collection of 13 million units of plasma to treat hemorrhagic shock. Acid-citrate-dextrose solution was developed by Loutit and Mollison in England in 1943 as part of the war effort and extended the shelf-life of red cells to 21 days.128 Edwin Cohn’s research in Boston on plasma fractionation to prepare albumin as a volume expander for battlefield hemorrhagic shock dramatically advanced protein chemistry and supplied fractions rich in immunoglobulins, prothrombin, fibrinogen, and anti-hemophilic factor (factor VIII).129,130 The accompanying clinical studies of hemorrhagic shock provided important physiological insights into the pathophysiology of the disorder.131-135

Studies on the treatment of burns with skin grafts by Medawar led to an understanding of the role of lymphocytes in cellular immunity.136,137 Most importantly, studies of radiation biology were conducted in concert with the development of atomic weapons. The effects of radiation exposure on hematopoiesis made hematologic research a high priority. For example, the finding from studies of the impact of the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that the drop in platelet count could serve as a radiation dosimeter that correlated with distance from ground zero and death from hemorrhage138,139 stimulated research by Cronkite and Brecher into better methods of counting platelets and the use of platelet transfusions to reverse radiation-induced hemorrhage.140 In his ASH oral history, James Tullis, the first president of ASH, recounted how after the war ended General George Marshall became the head of the American Red Cross and periodically visited Edwin Cohn’s laboratory where Tullis worked. Soon after Marshall learned that Tullis was considering working on platelets, Tullis got a call from the Red Cross to confirm that he was working on platelets, followed about a week later by a check from the Red Cross for $50 000, an extraordinary amount of money at that time, to support his research.

Studies of the effects of radiation exposure by Jacobson during the war at the University of Chicago141 were extended after the war to bone marrow transplantation142,143 and the search for erythropoietin.144 Jacobson later described how he was essentially ordered by Dean Taliaferro to create and direct the radiation safety measures for the scientists working on developing a nuclear weapon at the university.142 Studies by Jacobson and Lushbaugh on the effects of nitrogen mustard, a derivative of the mustard gas used as a battlefield weapon in World War I, led to the development of derivatives to treat lymphatic leukemia and Hodgkin disease, and to investigate the mitotic index of tissues.142,145,146 Radiation biology studies during the war also led to the generation of isotopes that were later used for a variety of cell kinetic studies and nuclear medicine diagnostic procedures. It is not surprising, therefore, that the entire scientific program for the ASH organizing meeting in 1957, at the height of the cold war and fears of nuclear attack, was devoted to new advances in bone marrow transplantation,2 including a presentation by E. Donnall Thomas, who would go on to receive the Nobel Prize for his pioneering studies of bone marrow transplantation in dogs and humans.143,147

Blood’s birth

In Blood’s inaugural issue in January 1946, George Minot wrote the foreword148 and quoted Andral’s 100-year-old definition of hematology as “a branch of the natural sciences for the study of blood,” but added that it is also a branch of internal medicine. He laid out a broad range of topics to be included: blood cells, plasma fractions, infections and leukocytes, coagulation, the genetics of blood disease, anemia, leukemia, polycythemia, purpura, heparin, dicoumarol, splenectomy, blood typing and transfusion, vitamin K and prothrombin, bone marrow cells, lymph nodes and their cells, industrial poisoning of blood cells, and the unique pediatric aspects of blood. At the same time, he emphasized that medicine deals with human hopes and fears and cautioned that “[a]t present science has outrun philosophy; narrow specialization is the order the day;” and “[i]n medicine things spiritual and things material must both be appreciated in considering any one person.” He concluded that, “The best clinical investigator must be an able clinician, have wide interests, and understand human beings. He (sic) must possess an active, creative imagination and scientific curiosity but the center of his (sic) activity must be the patient.”

Dameshek, the Editor-in-Chief, wrote an editorial briefly summarizing the evolution of hematology as a discipline, defining hematology as “a broad field with morphologic, clinical, physiologic, biochemical, and immunologic relationships.”149 He noted the need for a journal devoted to hematology in the United States, citing the “isolation or even extinction of leading European periodicals” due to the war. He ended with the hope that “[l]ike its name, Blood …will have universal interest, and thus perhaps serve as a small factor in fostering better international understanding.”

The “News and Views” section of the journal described the internal debates about selecting the name, Blood, with American Journal of Hematology and The Journal of Hematology also being considered.150 In the end, after polling the editors and with Minot’s strong endorsement, Blood, with the subtitle, Journal of Hematology, was selected, with the word “American” specifically removed by advice of “foreign advisors” to avoid “provincialism.” The editorial board was composed of a large number of prominent hematologists from the United States, Canada, and Latin America, with the promise of adding additional contributing editors from “Europe, South Africa, Australia, etc.”

The “News and Views” section also noted the creation of The New York Society for the Study of Blood, with Alexander Weiner serving as President. In addition, it cited newspaper reports from Japan of blood cell dyscrasias of individuals exposed to the atom bomb. “The atomic bomb, with its presumably great radioactivity, may have induced severe leukopenia and granulocytopenia in some individuals and thus may have resulted in agranulocytosis with its attendant sepsis.”

Blood’s growth

It is impossible to do justice to all of the scientific and clinical advances in hematology since Blood’s birth. In succeeding papers celebrating Blood’s 70th anniversary, past Editors-in-Chief will discuss select papers published during their terms of service that they think had a major impact on the field of hematology. To complement those papers, I have chosen to report on a number of metrics that provide some sense of the growth of Blood, the evolution of the conduct of hematologic research, and the research topics of most interest to investigators. I also highlight a few examples of the introduction (and persistence) of new techniques and therapies as witnessed by their appearance in papers published in Blood.

Blood’s appearance and size

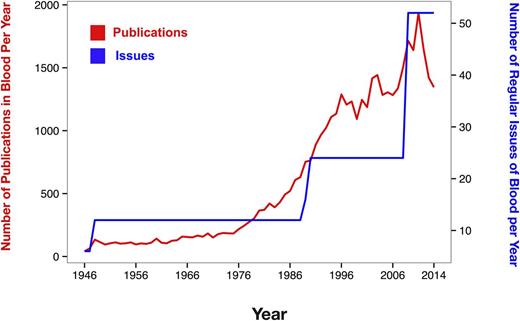

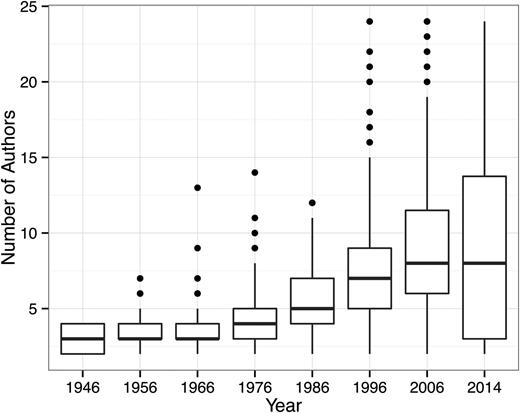

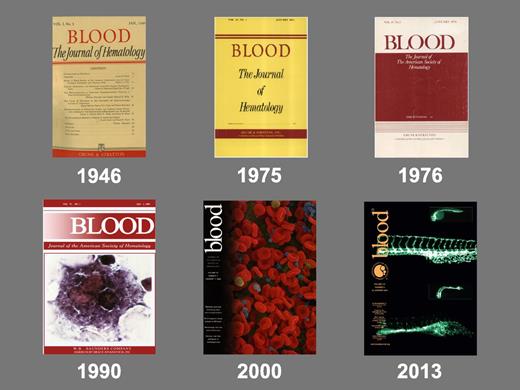

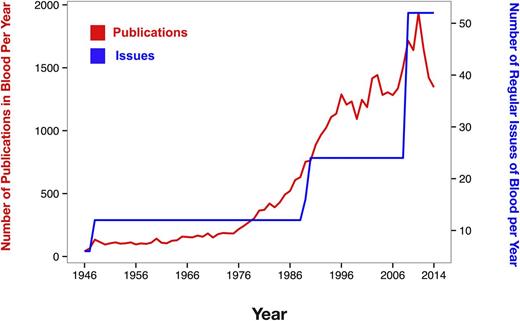

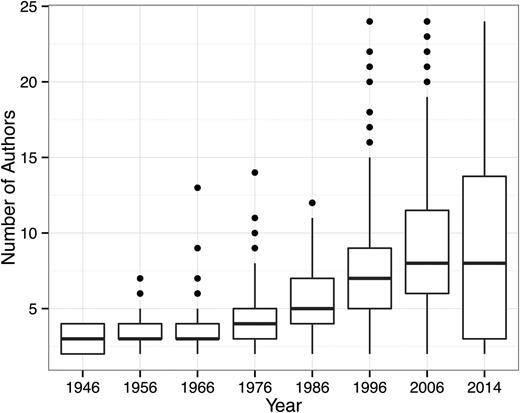

Figure 1 contains the cover of the first issue of Blood, as well as a cover of an early issue each time Blood changed the format of its cover. The covers reflect the evolution of academic publishing, aesthetic tastes, and the technology of journal printing, including changes in font, overall size, paper quality, and black and white and color photography. Figure 2 shows the increase in the number of papers and regular issues published yearly in Blood from 1946, when it started as a bimonthly publication, to 2014, when it was published on a weekly basis. As of the beginning of July 2015, Blood had published 125 volumes containing a total of 43 042 papers, including 2729 clinical trials (of which 775 were randomized controlled trials), 2345 case reports, 1153 multicenter studies, 1348 reviews, 39 meta-analyses, and 20 practice guidelines. Figure 3 reports the average number of authors per publication, demonstrating a dramatic increase over time, going from a median of ∼2.5 to ∼7.5 authors. The increase in the number of authors per paper is actually understated since the later journal issues contain commentaries that were mostly single-authored. These single-authored commentaries probably also account for the greater spread in the number of authors per paper. The data provide a compelling picture of the growth of hematologic research and advances in the clinical care of patients with hematologic disorders, as well as the increasing team-based nature of the science required to generate the data for a Blood publication.

The cover of the very first issue of Blood and the cover of an early issue of Blood each time the journal changed the format of its cover.

The cover of the very first issue of Blood and the cover of an early issue of Blood each time the journal changed the format of its cover.

The number of papers and regular issues published yearly in Blood from 1946, when it started as a bimonthly publication, to 2014, when it was published on a weekly basis.

The number of papers and regular issues published yearly in Blood from 1946, when it started as a bimonthly publication, to 2014, when it was published on a weekly basis.

The average number of Blood authors per publication. Note the dramatic increase over time, from a median of ∼2.5 authors to ∼7.5 authors.

The average number of Blood authors per publication. Note the dramatic increase over time, from a median of ∼2.5 authors to ∼7.5 authors.

Country of submission of published papers in Blood

In its first year (ie, 1946), Blood published 41 articles, of which 38 (93%) were contributed by American hematologists. The 3 non-US articles were from Hadassah University Hospital and Hebrew University (Jerusalem, Palestine); Hospitals of Brussels (Brussels, Belgium); and The University of Chile, the University of Concepción, and the Police Technical Laboratory of the Director General of Investigations, all in Chile. For comparison, Table 2 contains data on the number of papers published in Blood from 2006 to 2015 based on the country of submission. The data indicate that Blood has become an international journal, with nearly half of the manuscripts leading to published papers submitted from outside the United States. Submissions from the United Kingdom, Europe, Canada, Scandinavia, and Japan dominate the non-US submissions, with China just behind. Relative to the size of their populations, Israel, Singapore, and Taiwan stand out as contributing nations.

Subscriptions to Blood

Although data on subscriptions in Blood’s early years are not available, in 2014 there were 2920 institutional subscribers from 120 separate countries, further attesting to Blood’s global reach and the worldwide breadth of interest in the papers published in the journal.

Evolution of select topics in hematology in Blood

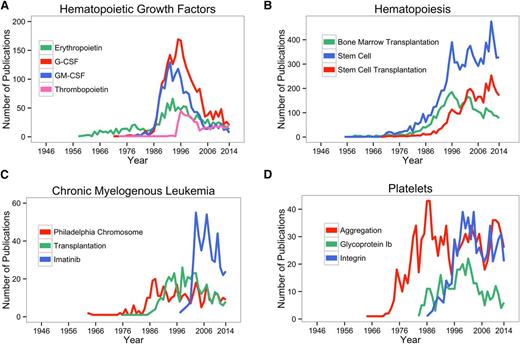

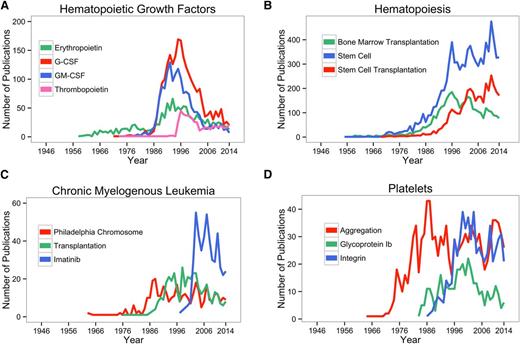

The number of papers published in Blood over time on specific topics provides an index of the evolution of the progress in hematology. Several examples are provided in Figure 4, in which the number of Blood papers containing a given search term are shown for the years 1946 to 2014. Figure 4A shows the data on hematopoietic growth factors: Figure 4B shows data on bone marrow transplantation, stem cells, and stem cell transplantation; Figure 4C on chronic myelogenous leukemia; and Figure 4D on platelet aggregation and glycoproteins. Each of the graphs provides a historical context for junior investigators entering the field and perhaps wistful nostalgia for senior investigators who lived through each of the discoveries and revelations.

The number of Blood papers containing the indicated search terms are shown for the years 1946 to 2014. (A) Hematopoietic growth factors; (B) hematopoiesis; (C) chronic myelogenous leukemia; and (D) platelets. G-CSF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-monocyte colony stimulating factor.

The number of Blood papers containing the indicated search terms are shown for the years 1946 to 2014. (A) Hematopoietic growth factors; (B) hematopoiesis; (C) chronic myelogenous leukemia; and (D) platelets. G-CSF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-monocyte colony stimulating factor.

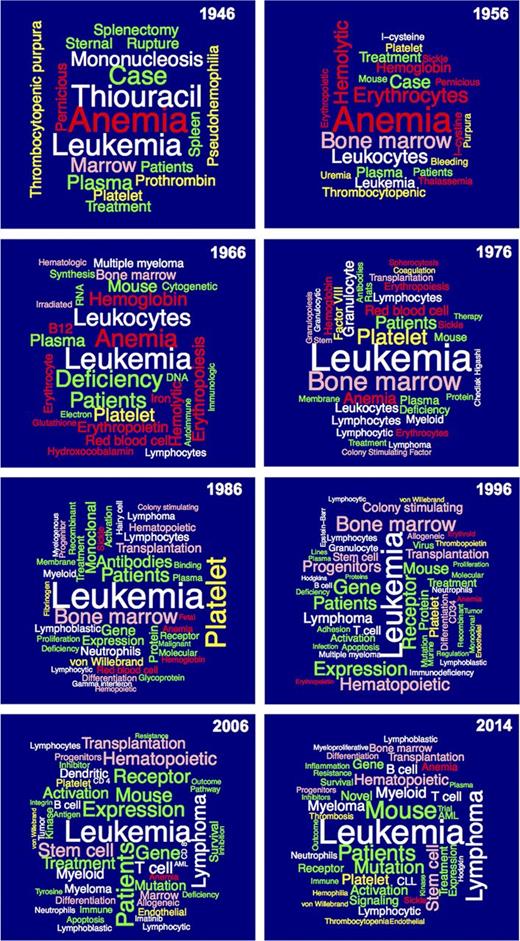

Topics of interest over time as judged by Blood paper title terms

Figure 5 contains “word clouds” of selected words from the titles of papers published in Blood by decade (1946, 1956, 1966, 1976, 1986, 1996, and 2006) and ending with data from 2014. The color code is red for RBC biology and disorders; white for WBC biology and disorders; yellow for hemostasis, thrombosis, and vascular biology; pink for hematopoiesis-related topics, including transplantation; and green for terms that cut across topics. The major trends that emerge are summarized below:

Terms related to RBC biology (red) increased from 1946 to 1966 and then declined quite dramatically through 2006, with an increase in 2014.

Leukemia has consistently occupied a prominent place in publications in Blood throughout its history; leukocyte biology was prominent in the period from 1956 to 1976; lymphocyte biology and pathology became prominent in 1966, expanding to T cell and B cell in 1996 and persisting to 2014; mononucleosis was an important subject of study in 1946 but not thereafter; multiple myeloma was of broad interest in 2006 and 2014; interferon and hairy cell leukemia were of interest in 1986; immunodeficiency was a focus of interest in 1996; imatinib treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia was featured in 2006; and JAK2 (Janus kinase 2) and CLL (chronic lymphocytic leukemia) appeared among the most common title terms in 2014.

Platelets (yellow) was an important topic as early as 1946, and then increased in relative importance over the next 40 years, after which it declined in relative importance; thrombocytopenia was prominent from 1946 to 1956 and reappeared in 2014; prothrombin was a focus of attention in 1946, factor VIII in 1976, fibrinogen in 1986, von Willebrand factor from 1986 to 2014, and thrombopoietin in 1998; endothelial cells have been prominent since 1996; and thrombosis and hemophilia gained new prominence in 2014.

Terms related to hematopoiesis (pink) are present throughout Blood’s history but have grown in prominence over the years; bone marrow reached its peak in 1976 but continued throughout; colony-stimulating factors reached prominence in 1986 and peaked in 1998; progenitor and/or stem cells first appeared in 1986 and have remained prominent thereafter; and transplantation first appeared in 1986 and has remained prominent thereafter, with a recent focus on graft-versus-host disease.

Terms that cut across the individual areas of hematology (green) grew in importance over time, with the spleen of particular early interest; autoimmunity and cytogenetics became featured in 1966; membrane biology in 1976 and 1986; monoclonal antibodies in 1986 and 1996; genes and receptors in 1986 and thereafter; mutations in 1996 and thereafter; apoptosis in 2006; and activation and cell signaling starting in 1986 and extending thereafter.

“Word clouds” of select terms from the titles of papers published in Blood in 1946, 1956, 1966, 1976, 1986, 1996, 2006, and 2014. The size of the term reflects the number of times it appeared in titles. In cases where two terms were very closely related (eg, “platelet” and “platelets”), the total of the two was used for the analysis and one of the two terms was selected for representation. Some terms were omitted when they did not convey specific information related to the development of hematology. Because the number of papers published in each year represented differed significantly, the number of replicates needed to be represented in the “word cloud” differed. The minimum of replicates each year required for inclusion were: 1946, 2; 1956, 3; 1966, 3; 1976, 5; 1986, 9; 1996, 23; 2006, 25; and 2014, 17. The numbers of replicates in the top-ranked terms were: 1946, 6; 1956, 19; 1966, 13; 1976, 42; 1986, 107; 1996, 200; 2006, 207; and 2014, 182. The terms are color-coded to reflect the broad disciplines: red for RBC biology and disorders; white for WBC biology and disorders; yellow for hemostasis, thrombosis, and vascular biology; pink for hematopoiesis-related topics, including transplantation; and green for terms that cut across topics.

“Word clouds” of select terms from the titles of papers published in Blood in 1946, 1956, 1966, 1976, 1986, 1996, 2006, and 2014. The size of the term reflects the number of times it appeared in titles. In cases where two terms were very closely related (eg, “platelet” and “platelets”), the total of the two was used for the analysis and one of the two terms was selected for representation. Some terms were omitted when they did not convey specific information related to the development of hematology. Because the number of papers published in each year represented differed significantly, the number of replicates needed to be represented in the “word cloud” differed. The minimum of replicates each year required for inclusion were: 1946, 2; 1956, 3; 1966, 3; 1976, 5; 1986, 9; 1996, 23; 2006, 25; and 2014, 17. The numbers of replicates in the top-ranked terms were: 1946, 6; 1956, 19; 1966, 13; 1976, 42; 1986, 107; 1996, 200; 2006, 207; and 2014, 182. The terms are color-coded to reflect the broad disciplines: red for RBC biology and disorders; white for WBC biology and disorders; yellow for hemostasis, thrombosis, and vascular biology; pink for hematopoiesis-related topics, including transplantation; and green for terms that cut across topics.

Conclusion

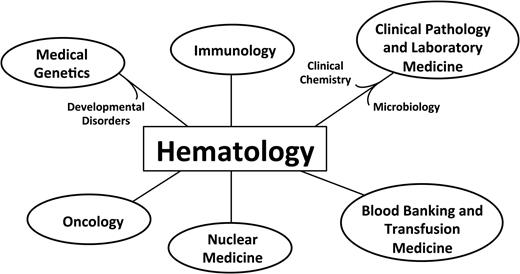

Blood has much to be proud of as it reaches this milestone birthday, as does the field of hematology, which Blood’s growth reflects. Dr Jane Desforges in her 1985 ASH presidential address, during the period when the stages of hematopoietic development and the respective growth factors were being elucidated, likened hematology to a “burst-forming unit” because it gave rise to so many other fields, a selection of which are depicted in Figure 6. Blood and hematology can look forward to the future with confidence as hematologic research and clinical care continue to advance, fueled by the energy of dedicated basic investigators, clinical investigators, and physician discoverers,151 all working together and using the scientific method to improve human health.

Hematology as a “burst-forming unit.” The figure indicates some of the disciplines that have emerged from hematology.

Hematology as a “burst-forming unit.” The figure indicates some of the disciplines that have emerged from hematology.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr Joel Correa da Rosa for his advice and expertise in organizing, analyzing, and displaying the bibliographic search data and the other demographic data on Blood publications, along with Paola da Silva Martins who assisted him; Suzanne Rivera for organizing and conducting the bibliographic searches and assisting with the data displays; John Borghi for advice on bibliographic searching and analysis; Virginia Ramsey for providing important data on Blood’s history and assisting with collecting the images of the Blood covers; Arlene Shaner for assisting with the Blood covers; and Bob Löwenberg for reviewing the manuscript and his insightful suggestions.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (UL1 TR000043) and the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL 19278).

Authorship

Contribution: B.S.C. conceived the format, conducted the research with the help of those indicated in the Acknowledgments, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Barry S. Coller, Allen and Frances Adler Laboratory of Blood and Vascular Biology, Rockefeller University, 1230 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: collerb@rockefeller.edu.