Key Points

We report the discovery of evolutionary conserved aging-associated accumulation of 4-1BBL+ B cells that induce GrB+ CD8+ T cells.

This discovery explains paradoxical retarded tumor growth in the elderly.

Abstract

Although the accumulation of highly-differentiated and granzyme B (GrB)-expressing CD8+CD28– T cells has been associated with aging, the mechanism for their enrichment and contribution to immune function remains poorly understood. Here we report a novel B-cell subset expressing 4-1BBL, which increases with age in humans, rhesus macaques, and mice, and with immune reconstitution after chemotherapy and autologous progenitor cell transplantation. These cells (termed 4BL cells) induce GrB+CD8+ T cells by presenting endogenous antigens and using the 4-1BBL/4-1BB axis. We found that the 4BL cells increase antitumor responses in old mice, which may explain in part the paradox of retarded tumor growth in the elderly. 4BL cell accumulation and its capacity to evoke the generation of GrB+CD8+ T cells can be eliminated by inducing reconstitution of B cells in old mice, suggesting that the age-associated skewed cellular immune responses are reversible. We propose that 4BL cells and the 4-1BBL signaling pathway are useful targets for improved effectiveness of natural antitumor defenses and therapeutic immune manipulations in the elderly.

Introduction

Immune cell compartment undergoes significant change in aged mammals, reflected by increased myelopoiesis and decreased lymphopoiesis.1-3 The decrease of B-cell progenitors in the bone marrow1-3 and lifelong antigen exposure skew the repertoire of B cells toward antigen-experienced memory and mature B cells at the expense of naïve B cells.4,5 Old mice also accumulate aging-associated B cells (ABCs) that are refractory to B-cell receptor and CD40 engagements6,7 and inhibitory for pro–B-cell survival,8 although some of them, such as B7-DC+ ABCs, can induce Th17 and Th1 cell polarizations.9 Autoreactive antibody-producing CD11c+ABCs are also found to accumulate in old mice.6 The decreased lymphopoiesis and thymic involution also result in a reduction of naïve T cells and increasing frequency of memory T cells,10,11 such as antigen-experienced memory T cells that respond to low-threshold stimuli and secrete cytotoxic factors, such as perforin and granzyme B (GrB).12,13 For example, the elderly accumulate highly differentiated CD8+CD28Low/– T cells10,14 expressing GrB,15 although a similar type of potentially cytotoxic cells are also induced after cytomegalovirus (CMV) and HIV infections (see Strioga et al16 ); in some autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Graves disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), type 1 diabetes (T1D), and Wegener’s granulomatosis17-19 ; and in patients with inflammatory breast cancer after high-dose chemotherapy followed with autologous progenitor cell transplantation (auto-HSCT).20 We recently found that antitumor effector GrB+CD8+ T cells can also be induced when tumor-supporting regulatory B cells (Bregs) are rendered into activators expressing 4-1BBL.21

Here, given the importance of 4-1BBL in CD8+ T-cell induction22-24 and the pathogenic role of B cells in autoimmune disorders,25,26 we hypothesized that the accumulation of 4-1BBL+B cells could be responsible for the expansion of GrB+CD8+ T cells in the elderly. To test this idea, we evaluated 4-1BBL+ B cells and GrB+CD8+ T cells in mammals, such as in healthy human participants of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), rhesus macaques, and mice. We found that both cell types are significantly increased in old mammals, where the accumulated 4-1BBL+ B cells (termed 4BL cells) induce GrB+CD8+ T cells acting through 4-1BBL/4-1BB and TCR/MHC axes. Our modeling studies in mice suggest that, as a functional consequence, the 4BL cell expansion also explains a paradoxical reduced growth of some tumors in old mice and humans, as contrasted with tumor growth in the young.27-30 The 4BL cells induce antitumor GrB+CD8+ T cells by presenting self-tumor antigen, gp100, and retard growth of poorly immunogenic B16 melanoma in old mice. In concordance, the expansion of potentially antitumor GrB+CD28LowCD8+ T cells in auto-HSCT patients with inflammatory breast cancer20 appears to be also caused by 4BL cells. Overall, we provide a mechanistic proof of the existence of a new type of effector B cells, 4BL cells, accumulated in aging. These potentially pathogenic and/or beneficial cells can probably be targeted to alleviate autoimmune responses or to enhance antitumor cellular responses in the elderly.

Methods

Human, macaque, and mouse samples

Human peripheral blood (PB) from old (n = 28; 79.4 ± 5.8 years) and young (n = 18; 42.1 ± 8.9 years) healthy participants of the BLSA (National Institute of Aging [NIA]) and healthy volunteers was collected under the Human Subject Protocol #2003054 and Tissue Procurement Protocol #2003-076. Auto-HSCT patients had been treated for inflammatory breast cancer at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) between September 1996 and 2008 under protocol 96-C-0104.20 This study was conducted with the approval of the NCI Institutional Review Board. All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The PB from young (11-14 years) and old (19-30 years) Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta, n = 28) was collected under Animal Study Protocol 434-OSD-2015. Young (5-8 weeks) female C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice and congenic μMT mice with B-cell deficiency (B6.129P2-Igh-Jtm1Cgn/J) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Young (5-8 weeks) TCR transgenic pmel-1 mice were housed at the NIA,31 and congenic 4-1BB–deficient mice (4-1BB KO) were previously reported.22,32 Old female C57BL/6 (20-22 months) were obtained from Aged Rodent Colony, NIA.

Flow cytometry antibodies

Antibodies (Ab) were obtained from BioLegend unless otherwise specified. Human cells were stained with the following anti-human Ab: CD45-Pacific blue (clone HI30), CD19-APC (clone HIB19), CD3-FITC (clone UCHT1; BD Biosciences), CD4-PECy5.5 (clone OKT4), and CD8-PE (clone HIT8a), CD28-FITC (clone CD28.2; BD Biosciences); IgM-FITC (clone MHM-88); IgD-PE (clone IA6-2); CD27-PECy7 (clone LG.3A10); CD24-Brilliant violet 421 (clone M1/69); CD38-PerCP5.5 (clone HIT2); CD40-PECy7 (clone 5C3); CD80-Brilliant violet 421 (clone 2D10); CD86- PerCP5.5 (clone IT2.2); 41BBL-PE (clone 5F4); HLA-DR-FITC (clone G46-6; BD Biosciences); and HLA-A, B, C-PE (clone G46-2.6; BD Biosciences). Anti-human Abs for intracellular staining were GrB-FITC (clone GB11), GrA-Pacific blue (clone CB9), perforin-Alexa Fluor 647 (clone dG9), and interferon (IFN)γ-PECy7 (clone 4S.B3; eBioscience). For staining of monkey cells, we used anti-human Abs: CD8-PECy7 (clone RPA-T8; eBioscience), GrB Alexa Fluor 647 (clone GB11), and IFNγ- FITC (clone B27, BD Biosciences) Abs. Mouse cells were stained with anti-mouse Abs: CD19-PerCP5.5 (clone 6D5), CD21-APC (clone 7E9), CD23-Pacific blue (clone B3B4), CD5-FITC (clone 53-7.3), CD1d-PE (clone 1B1), CD80-PE (clone 16- 10A1; BD Biosciences), CD86-FITC (clone GL1, BD Biosciences), 41BBL-PE (clone TKS-1), I-Ab-Pacific blue (Clone AF-6-120.1), H-2Kb-PE (clone AF6-88.5; BD Biosciences); and H-2Db-FITC (clone KH95), CD8-PE (clone 53-6.7), and anti- human/mouse GrB-FITC (clone GB11). Freshly isolated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells or murine cells were activated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (5 ng/mL) + ionomycin (500 ng/mL, R&D), and monensin (2 μM, eBiosciences) for 5 hours at 37°C. Intracellular staining was performed using the Intracellular Fixation and Permeabilization buffers kit (eBiosciences) as directed by the manufacturer. See supplemental Data on the Blood Web site for more information.

In vitro assays

B cells from human PB and murine spleens were negatively isolated using the B-cell Isolation Kit II (≥98% purity; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and the EasySep Mouse B-cell Isolation Kit (≥95% purity; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, ON, Canada), respectively. To test induction of GrB in CD8+ T cells, B cells were cultured with negatively isolated CD3+ T cells (human T-cell enrichment columns, R&D Systems) from allogeneic young donors for 5 days at 1:1 ratio in complete RPMI medium (cRPMI; Invitrogen) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Murine CD3+ T cells (isolated from spleens with T cell–enrichment columns, R&D Systems, and labeled with eFluor670; eBioscience) were similarly mixed with B cells either pulsed with 3 μg/mL gp10025-32 peptide (or irrelevant control peptide SPANX; ANAspec, Fremont, CA) or stimulated with 1.5 μg/mL anti-CD3 Ab (BD Biosciences) for 5 days in cRPMI. For the 4-1BBL/4-1BB axis study, B and T cells were cultured in the presence of 10 μg/mL blocking (or isotype controls) Abs to 4-1BBL (clone TKS-1, Rat IgG2a; BioLegend), CD80 (clone 16-10A1, Armenian Hamster; eBiosciences), and CD86 (clone GL1, Rat IgG2a; eBioscience); or 5 μg/mL of antagonistic anti-human 4-1BB Ab (clone BBK-2, mouse IgG1; Thermo Scientific).

In vivo manipulations

Animals were housed in a pathogen-free environment at the NIA Animal Facility (Baltimore, MD) as outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health [NIH] Publication No. 86-23, 1985). Female C57BL/6 or congenic μMT mice were subcutaneously (s.c.) challenged with 105 B16-F10 melanoma cells (American Type Culture Collection). B cells were depleted by 2 intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of anti-CD20 antibody (250 μg/mouse, clone 5D2; Genentech, Inc., San Francisco, CA). Control IgG was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). For adoptive transfer experiments, mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with splenic B cells (5 × 106, ≥95% pure) 1 day before and 5 days after the B16 melanoma challenge. For vaccine study, 24-month-old mice (10 per group) were twice intraperitoneally immunized one week apart with 3 μg hemagglutinin (HA) of A/California/7/2009 (H1N1), A/Victoria/361/2011 (H3N2), B/Wisconsin/1/2010 strains (about 1/5 inoculum of the human influenza vaccine dose, VAXIGRIP; Statens Serum Institut, Denmark), and serum Ab response to egg-derived HA from A/California/7/2009 (NIBRG-121xp) was measured after 4 weeks by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. For in vivo Ag-specific CD8+GrB+ T cell expansion, μMT mice with B16 melanoma were i.v. injected with 5 × 106 splenic B cells from young, Old-IgG or Old-restored mice together with 5 × 106 eFluor670-labeled CD8+ T cells from naïve pmel mice. After 7 days, CD8+ T cells were quantified using gp100 dextramer IMDQVPFSV (Immudex, Copenhagen, Denmark) or Vβ13-PE Ab (clone MR12-4, BioLegend). Antagonistic anti-mouse 4-1BBL Ab or control rat IgG (100 μg each) were i.p. injected at days 1, 4, 8, and 11 post-B16 melanoma challenge. One half of anti-mouse 41BBL Ab-treated mice were also adoptively transferred with 2 × 107 splenic B cells from old mice 13 days after the tumor challenge.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). To assess significance, we used Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) for Student unpaired t test and the Mann-Whitney U and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests; a P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Aging mammals accumulate 4-1BBL+ B cells and GrB+CD8+ T cells

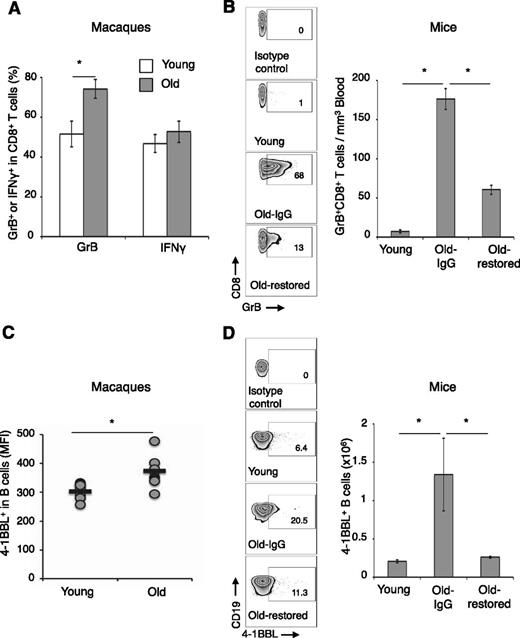

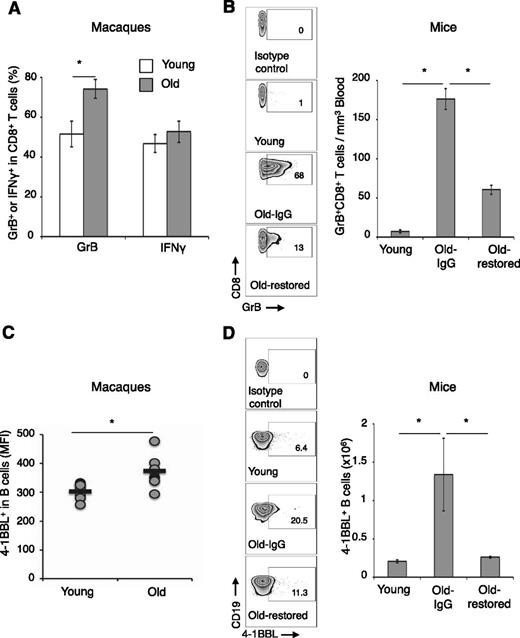

Given its importance in CD8+ T-cell induction,22-24 and that B cells can elicit antitumor GrB+CD8+ T cells using 4-1BBL,21 we hypothesized that 4-1BBL+ B cells could also be responsible for the age-associated expansion of CD8+CD28Low T cells expressing GrB.10 To test this idea, the 2 cell types were evaluated in the PB of old (79 ± 6 years) and young (42 ± 9 years) healthy humans. Despite an overall reduction in CD3+ cells and CD8+ T cells (supplemental Figure 1A-C), the CD8+CD28Low T cells expressing GrB, GrA, and perforin were significantly enriched in old compared with young (Figure 1A and supplemental Figure 1D-E). There was no difference in CD8+ T cells producing IFNγ (supplemental Figure 1F). Although 4-1BBL+ B cells usually represent a minor (<3%) population of B cells,33 the B cells of the elderly were significantly enriched for 4-1BBL expressers compared with young (respectively, 13.4 ± 2 vs 5.8 ± 1.8, P = .009, Student t test; and P = .008/P = .003, Mann-Whitney U and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, Figure 1B). The 4-1BBL+ B cells appear to be a subset of antigen-experienced CD27+ memory cells that are CD86High and HLA-IHigh HLA-DRInter/LowCD40Low (Figure 1C and supplemental Figure 2A-E). Hence, GrB+CD8+ T cells and 4-1BBL+ B cells are coenriched in the elderly. Because auto-HSCT patients with inflammatory breast cancer also contain elevated levels of GrB+CD8+ cells,20 they could also be coenriched with 4-1BBL+ B cells. Indeed, 4-1BBL+ B cells were increased (above an arbitrary 6% of healthy young donors; Figure 1D) in 6 of 11 patient samples with the enriched GrB+CD28LowCD8+ T cells (Figure 1E-F). We also tested whether the accumulation is conserved in mammals and found that GrB+CD8+ T cells (Figure 2A-B and supplemental Figure 3A-C) and 4-1BBL+ B cells (Figure 2C-D) were significantly enriched in old rhesus macaques and mice. As in humans, old macaque (supplemental Figure 3D) and old mouse (supplemental Figure 3E-F) 4-1BBL+ B cells expressed high levels of CD86 and MHC class I. Of note, as others reported,16,34,35 old mouse CD8+ T cells did not reduce CD28.

The elderly accumulate GrB+CD8+ T cells and 4-1BBL+ B cells. (A-B) Proportions of CD28Low/- (i) and GrB+-expressing CD8+ T cells (ii) and for 4-1BBL+ B cells (B) are increased in the elderly (Old, n = 28), compared with the young (Young, n = 18). Shown are CD28 (i, a representative histogram) and GrB (ii, mean ± SEM) expressions in gated PB CD8+ T cells, and a representative dot plot (%; B, upper panel) and a summary whiskers-and-box plot (Student t test P = .009, Mann-Whitney U test P = .008, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P = .003; B, lower panel) of 4-1BBL in gated CD19+ B cells. (C) The 4-1BBL+ B cells in old human donors (black line) also are CD27+ CD40+ CD86High HLA-IHigh but HLA-DRLow, compared with the 4-1BBL– B cells (dotted line). (D-F) 4-1BBL+CD19+ B cells were enriched in some patients with inflammatory breast cancer after auto-HSCT (n = 11, D). 4-1BBL+ CD19+ B cells (gated in CD19+ cells, D) were enriched above the 6% level of arbitrary threshold set for healthy donors. The samples were also enriched for GrB+CD28LowCD8+ T cells (mean ± SEM [E-F]). *P < .05 was considered significant.

The elderly accumulate GrB+CD8+ T cells and 4-1BBL+ B cells. (A-B) Proportions of CD28Low/- (i) and GrB+-expressing CD8+ T cells (ii) and for 4-1BBL+ B cells (B) are increased in the elderly (Old, n = 28), compared with the young (Young, n = 18). Shown are CD28 (i, a representative histogram) and GrB (ii, mean ± SEM) expressions in gated PB CD8+ T cells, and a representative dot plot (%; B, upper panel) and a summary whiskers-and-box plot (Student t test P = .009, Mann-Whitney U test P = .008, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P = .003; B, lower panel) of 4-1BBL in gated CD19+ B cells. (C) The 4-1BBL+ B cells in old human donors (black line) also are CD27+ CD40+ CD86High HLA-IHigh but HLA-DRLow, compared with the 4-1BBL– B cells (dotted line). (D-F) 4-1BBL+CD19+ B cells were enriched in some patients with inflammatory breast cancer after auto-HSCT (n = 11, D). 4-1BBL+ CD19+ B cells (gated in CD19+ cells, D) were enriched above the 6% level of arbitrary threshold set for healthy donors. The samples were also enriched for GrB+CD28LowCD8+ T cells (mean ± SEM [E-F]). *P < .05 was considered significant.

The accumulation of GrB+CD8+ T cells and 4-1BBL+ B cells is evolutionarily conserved in old mammals. (A,C) In rhesus macaques (PB) and (B,D) mice (spleen). Shown is the mean ± SEM of GrB+ within CD8+ T cells in macaques (A, %) and in mice (B, representative dot plots, %, left panel; and absolute #, right panel) and 4-1BBL+ B cells in gated macaque CD20+ cells (MFI, C) and splenic murine CD19+ cells (B, representative dot plots, %, left panel; and absolute #, right panel). The increase of 4-1BBL+ B cells and GrB+CD8+ T cells in old mice is lost after regeneration of B cells induced with anti-CD20 Ab treatment (B,D, Old-restored). Control old mice (Old-IgG) were treated with isotype control Ab. (B,D) Representative results of 5-mice-per-group experiment independently reproduced 4 times. No correlation between age and IFNγ+CD8+ T cells was detected (A).

The accumulation of GrB+CD8+ T cells and 4-1BBL+ B cells is evolutionarily conserved in old mammals. (A,C) In rhesus macaques (PB) and (B,D) mice (spleen). Shown is the mean ± SEM of GrB+ within CD8+ T cells in macaques (A, %) and in mice (B, representative dot plots, %, left panel; and absolute #, right panel) and 4-1BBL+ B cells in gated macaque CD20+ cells (MFI, C) and splenic murine CD19+ cells (B, representative dot plots, %, left panel; and absolute #, right panel). The increase of 4-1BBL+ B cells and GrB+CD8+ T cells in old mice is lost after regeneration of B cells induced with anti-CD20 Ab treatment (B,D, Old-restored). Control old mice (Old-IgG) were treated with isotype control Ab. (B,D) Representative results of 5-mice-per-group experiment independently reproduced 4 times. No correlation between age and IFNγ+CD8+ T cells was detected (A).

Increased GrB+CD8+ T cells require 4-1BBL+ B cells in vivo

To elucidate the relationship between 4-1BBL+ B cells (henceforth designated 4BL cells) and GrB+CD8+ T cells, we depleted B cells in 20-month-old mice with anti-CD20 Ab (Old-depleted; supplemental Figure 4A-B). As early as 2 weeks after B-cell depletion, the GrB+CD8+ T cells were drastically reduced in old mice (P < .05, Old-depleted vs Old-IgG; supplemental Figure 4B). Their numbers did not recover even after B-cell compartment was restored 40 days post B-cell depletion (Old-restored mice; Figure 2B and supplemental Figure 3B-C). Although B-cell compartment was presumably “rejuvenated,”36 because transitional AA4.1+CD19+ B cells were significantly increased reaching the levels of young mice (supplemental Figure 4A-B) and influenza vaccine response was slightly improved (supplemental Figure 4C), the Old-restored mice failed to augment 4BL cells, which remained low as they did in Young mice (Figure 2D). Hence, 4BL cells may be responsible for the accumulation of GrB+CD8+ T cells.

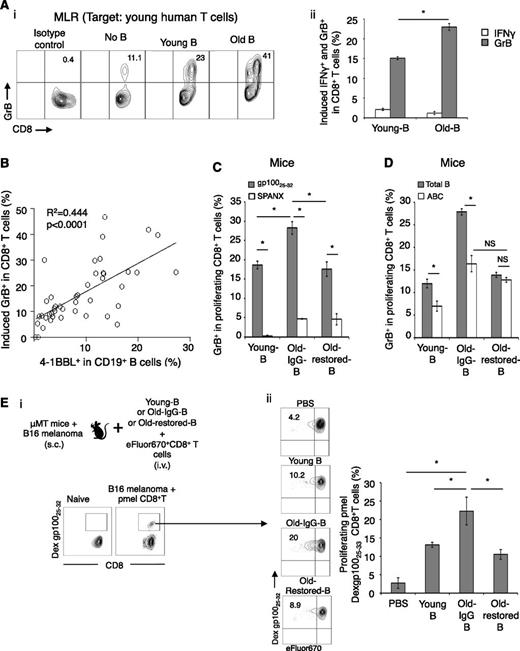

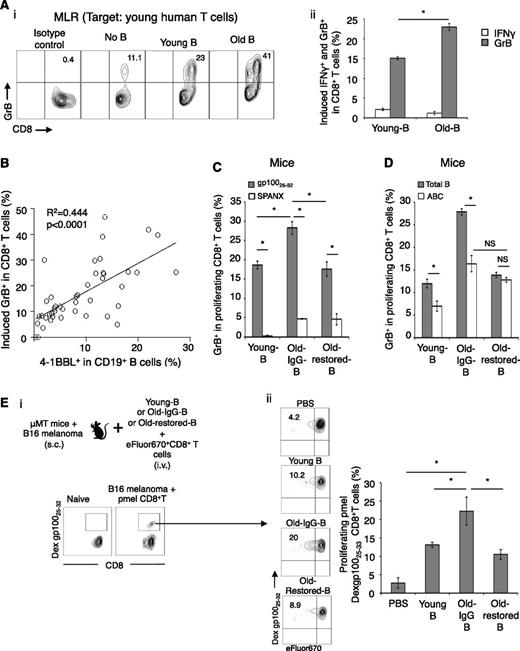

4BL cells induce GrB+CD8+ T cells

To test this possibility, we first performed mixed lymphocyte reaction by coculturing B cells of young and old people with young-subject T cells. B cells induced GrB in CD8+ T cells, but the extent of the induction was significantly greater if the B cells were from the elderly (Figure 3A). The mixed lymphocyte reaction was not affected by presence or absence of anti-CD3 Ab (not depicted), ruling out differences in TCR stimulation. No effect was detected on IFNγ expression (Figure 3Aii). A larger sample test (26 old and 18 young people) indicated that the induction of GrB in CD8+ cells was highly associated with the expression of 4-1BBL on B cells (P < .0001, Figure 3B). To confirm these results for mice, B cells from old and young mice were cocultured with syngeneic T cells or TCR transgenic CD8+ T cells (from congenic pmel mice specific for a self-antigen gp100 involved in pigment synthesis and also expressed in malignant melanoma cells31 ). Again, the B cells of old mice induced significantly stronger GrB expression in CD8+ T cells (P < .05, Figure 3C and supplemental Figure 4D). Importantly, this enhancing effect was completely lost if B cells were from Old-restored mice (P < .05, Old-restored-B vs Old-IgG-B; Figure 3C-D and supplemental Figure 4D), where the B-cell rejuvenation failed to accumulate 4BL cells and GrB+CD8+ T cells (Figure 2D-C). In contrast, ABCs (another B-cell type accumulated in old mice6,7 ) remained enriched in Old-restored mice (supplemental Figure 4E) and failed to increase GrB+CD8+ T cells in vitro (Figure 3D). Together, these data suggest that 4BL cells induce GrB+CD8+ T cells in vitro. The induction required TCR and costimulatory molecules, because it was lost in the absence of anti-CD3 Ab (supplemental Figure 4F) or cognate gp100 antigen (Figure 3C), or if CD80 and CD86 were blocked with respective antibody (supplemental Figure 4G).

4BL cells induce GrB+CD8+ T cells. (A) Old human B cells induce higher GrB expression in target CD8+ T cells from young donors in mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR). Shown GrB and IFNγ induction in CD8+ T cells (i, representative dot plot, %) and its mean (ii, % after deducting background response without B cells, No B) ± SEM examined in triplicate experiments and reproduced at least 3 times. (B) Positive correlation (P < .0001) between the induction of GrB (y-axis) in young CD8+ T cells and 4-1BBL expression levels on B cells (x-axis). (C) Murine 4BL cells induce GrB in TCR transgenic pmel CD8+ T cells by presenting cognate antigen (gp10025-32 peptide). eFluor670-labeled pmel CD8+ T cells were in vitro stimulated with B cells from young, Old-IgG, and Old-restored mice (as in Figure 2D) pulsed with gp10025-32 (gray bars) or control SPANX peptide (open bars). Shown is the mean ± SEM (%) of GrB within proliferating pmel CD8+ T cells in triplicate experiments reproduced 3 times. (D) ABCs (sort-purified, open bars) from young and old mice (as in Figure 2C) were compared with total B cells (gray bars) for the ability to induce GrB+CD8+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 Ab. (E) To demonstrate the 4BL cell-induced in vivo expansion of GrB+CD8+ T cells, naïve old mouse B cells and eFluor670-labeled CD8+ T cells from naïve congenic mice were i.v. injected into μMT mice bearing B16 melanoma (schema). One week later, GrB was quantified within proliferating LN CD8+ T cells using gp10025-32 dextramer. Shown are a representative dot plot (i-ii, %) and mean ± SEM (ii, %) of a 4 to 5-mice-per-group experiment independently reproduced 2 times.

4BL cells induce GrB+CD8+ T cells. (A) Old human B cells induce higher GrB expression in target CD8+ T cells from young donors in mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR). Shown GrB and IFNγ induction in CD8+ T cells (i, representative dot plot, %) and its mean (ii, % after deducting background response without B cells, No B) ± SEM examined in triplicate experiments and reproduced at least 3 times. (B) Positive correlation (P < .0001) between the induction of GrB (y-axis) in young CD8+ T cells and 4-1BBL expression levels on B cells (x-axis). (C) Murine 4BL cells induce GrB in TCR transgenic pmel CD8+ T cells by presenting cognate antigen (gp10025-32 peptide). eFluor670-labeled pmel CD8+ T cells were in vitro stimulated with B cells from young, Old-IgG, and Old-restored mice (as in Figure 2D) pulsed with gp10025-32 (gray bars) or control SPANX peptide (open bars). Shown is the mean ± SEM (%) of GrB within proliferating pmel CD8+ T cells in triplicate experiments reproduced 3 times. (D) ABCs (sort-purified, open bars) from young and old mice (as in Figure 2C) were compared with total B cells (gray bars) for the ability to induce GrB+CD8+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 Ab. (E) To demonstrate the 4BL cell-induced in vivo expansion of GrB+CD8+ T cells, naïve old mouse B cells and eFluor670-labeled CD8+ T cells from naïve congenic mice were i.v. injected into μMT mice bearing B16 melanoma (schema). One week later, GrB was quantified within proliferating LN CD8+ T cells using gp10025-32 dextramer. Shown are a representative dot plot (i-ii, %) and mean ± SEM (ii, %) of a 4 to 5-mice-per-group experiment independently reproduced 2 times.

To demonstrate the in vivo ability of 4BL cells to induce GrB+CD8+ T cells, we adoptively transferred eFluor670-labeled naïve pmel CD8+ T cells together with naïve B cells from young or old mice (Young-B and Old-B, respectively; Figure 3E) into congenic B cell–deficient μMT mice. Mice were challenged with B16 melanoma to provide a source of endogenous self-antigen, gp100, and one week later, we quantified GrB within proliferating (eFluor670-diluted) CD8+ T cells using gp10025-32 peptide-dextramer and the TCR-specific Vβ13 Ab in draining lymph nodes. Although DCs are potent activators of CD8+ T cells, surprisingly, GrB induction required B cells (P < .05, Young-B vs PBS; Figure 3E). However, the extent of GrB induction was again significantly higher if the B cells were from old mice (P < .05, Old-IgG-B vs Young-B; Figure 3E and supplemental Figure 5A). In contrast, this enhancing ability was lost in B cells from Old-restored mice (P < .05, Old-restored-B vs Old-IgG-B, Figure 3E and supplemental Figure 5A), where we did not detect 4BL cells after B-cell reconstitution (Figure 2D). Thus, 4BL cells can induce GrB+CD8+ T cells in vivo by presenting endogenously expressed self-tumor antigen.

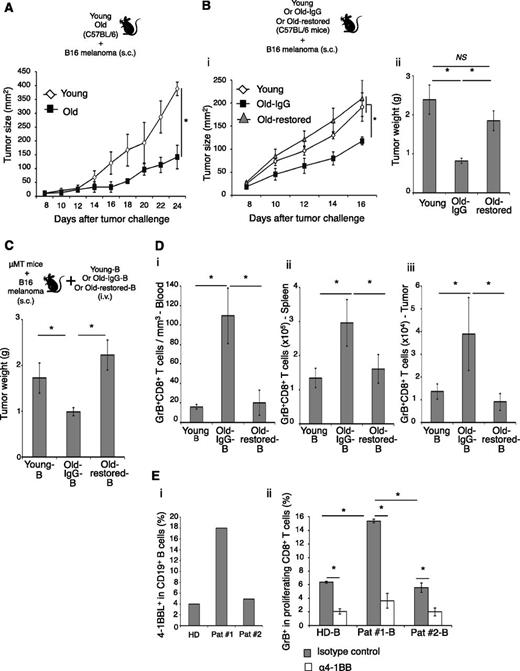

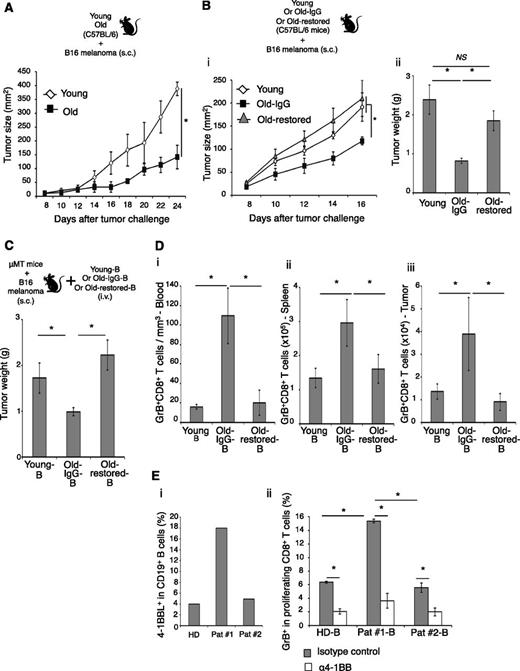

4BL cells retard B16 melanoma growth in old mice

To understand the biological relevance of the 4BL cell accumulation in aging, we challenged young (5 weeks old) and old (20 months old) C57BL/6 mice with a lethal dose of B16 melanoma cells. The growth of B16 melanoma was significantly retarded in old mice (P < .01, Old vs young; Figure 4A), as others have reported.37,38 The effect was lost in Old-restored mice (which also lost 4BL/GrB+CD8+ T cells), where melanoma grew as well as in young mice (P < .05, Old-restored vs Old-IgG; Figure 4B), suggesting that 4BL cells may retard tumor growth in old mice. To test this possibility, μMT mice with B16 melanoma were adoptively transferred with B cells from young, or Old-IgG, or Old-restored mice (Figure 4C). Unlike the B cells of young, the transfer of B cells from Old-IgG mice significantly reduced melanoma growth (P < .05, Old-IgG-B vs young-B; Figure 4C) and increased GrB+CD8+ T cells in PB, the secondary lymphoid organs, and the tumor (P < .05, Figure 4D and supplemental Figure 5B), a key antitumor requirement.39 The GrB+CD8+ T cells also were strongly expanded ex vivo if pulsed with gp10025-32 peptide (supplemental Figure 5C), confirming the tumor (gp100) specificity. However, both the tumor retardation (Figure 4C) and the GrB+CD8+ T-cell increase (Figure 4D and supplemental Figure 5B-C) were lost if the mice received B cells from Old-restored mice, which were deficient in 4BL cells (Figure 2D). Thus, 4BL cells retard B16 melanoma progression in old mice by eliciting antigen-specific GrB+CD8+ T cells. Similar mechanism may also exist in humans, because B cells from auto-HSCT breast cancer patients with high levels of 4-1BBL+ B cells (>6% threshold of young humans; Figure 1E and Figure 4Ei) induced significantly stronger GrB in the CD8+ T cells of healthy donors (P < .05, Pat #1 vs Pat #2-B or HD-B; Figure 4Eii).

4BL cells induce GrB+CD8+ T cells and retard tumor growth in old mice. The retarded B16 melanoma growth in old syngeneic mice (A) is lost in Old-restored mice (B). Young, Old-IgG, and Old-restored C57BL/6 mice (as in Figure 2B,D) were s.c. challenged with 105 B16 melanoma cells. (C) 4BL cells are responsible for the retarded tumor growth. μMT mice with B16 melanoma were adoptively transferred with B cells from young mice (Young-B), Old-IgG mice (Old-IgG-B), or Old-restored mice (Old-restored-B). B16 melanoma growth in (C) correlates with the expansion of GrB+CD8+ T cells in PB (i), spleen (ii), and tumor (iii). Shown are mean tumor size (mm2) ± SEM (A-Bi), final tumor weight (g) ± SEM (Bii-C), and GrB+CD8+ T cells ± SEM (number ×105, D) of 4 to 5-mice-per-group experiments independently reproduced at least 2 times. (E) Shown are a representative result showing differences in 4-1BBL+ B cells between auto-HSCT patient samples used, such as high (18%, Pat #1B) and low (4%, Pat #2, i) and their in vitro ability to induce GrB expression within healthy young people CD8+ T cells (mean ± SEM of triplicate experiment, ii). Control healthy donor B cells (HD, i-ii) contained <6% 4-1BBL+ B cells (as in Figure 1B). The GrB induction was completely blocked in the presence of antagonistic anti-4-1BB Ab (α4-1BB), but in not control Ab (ii).

4BL cells induce GrB+CD8+ T cells and retard tumor growth in old mice. The retarded B16 melanoma growth in old syngeneic mice (A) is lost in Old-restored mice (B). Young, Old-IgG, and Old-restored C57BL/6 mice (as in Figure 2B,D) were s.c. challenged with 105 B16 melanoma cells. (C) 4BL cells are responsible for the retarded tumor growth. μMT mice with B16 melanoma were adoptively transferred with B cells from young mice (Young-B), Old-IgG mice (Old-IgG-B), or Old-restored mice (Old-restored-B). B16 melanoma growth in (C) correlates with the expansion of GrB+CD8+ T cells in PB (i), spleen (ii), and tumor (iii). Shown are mean tumor size (mm2) ± SEM (A-Bi), final tumor weight (g) ± SEM (Bii-C), and GrB+CD8+ T cells ± SEM (number ×105, D) of 4 to 5-mice-per-group experiments independently reproduced at least 2 times. (E) Shown are a representative result showing differences in 4-1BBL+ B cells between auto-HSCT patient samples used, such as high (18%, Pat #1B) and low (4%, Pat #2, i) and their in vitro ability to induce GrB expression within healthy young people CD8+ T cells (mean ± SEM of triplicate experiment, ii). Control healthy donor B cells (HD, i-ii) contained <6% 4-1BBL+ B cells (as in Figure 1B). The GrB induction was completely blocked in the presence of antagonistic anti-4-1BB Ab (α4-1BB), but in not control Ab (ii).

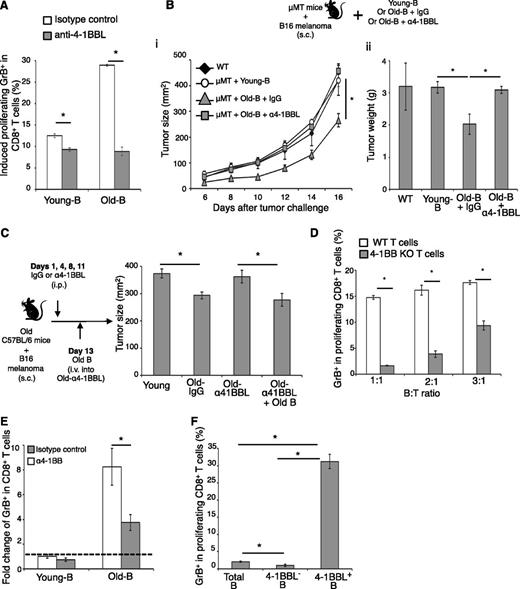

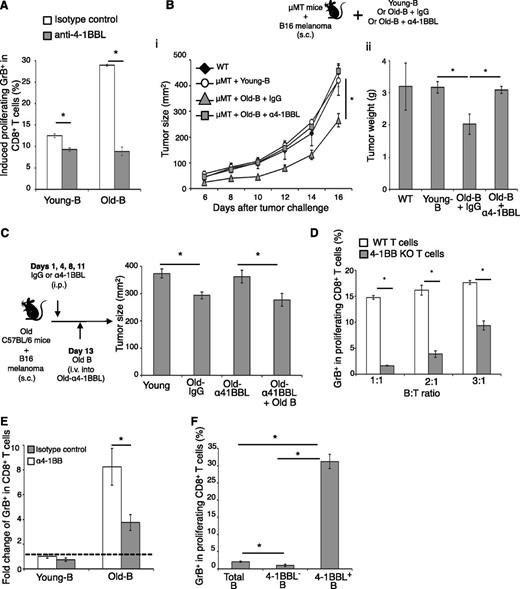

4BL cells induce GrB+CD8+ T cells via 4-1BBL/4-1BB axis

Given the importance of 4-1BBL/4-1BB axis in CD8+ T-cell activation,22-24 4BL cells probably require 4-1BBL for the induction of GrB+CD8+ T cells. To test this idea, we first blocked 4-1BBL on 4BL cells using antagonistic 4-1BBL Ab and found that the Ab, but not the control Ab, almost completely disabled the enhanced ability of old-mouse B cells to induce GrB in CD8+ T cells (Old-B; Figure 5A). Similarly, the 4-1BBL Ab-pretreated B cells from old mice also failed to retard melanoma growth, if adoptively transferred into tumor-bearing congenic μMT mice (P < .05, μMT+Old-B+α4-1BBL vs Old-B; Figure 5B). Treatment with anti-4-1BBL Ab alone also abrogated the retarded B16 melanoma growth in old WT mice, resulting in tumor growth to be as rapid as in young mice (Old-α4-1BBL; Figure 5C). However, the retarded tumor growth was restored if these mice were subsequently transferred with B cells from naïve old mice (P < .05, Old-α41BBL+Old-B; Figure 5C). Conversely, the induction of GrB required 4-1BB on CD8+ T cells, because T cells from 4-1BB–deficient mice failed to respond (4-1BB KO, P < .001; Figure 5D). Similarly, the antagonistic 4-1BB Ab, but not the control Ab, also blocked the induction of GrB+CD8+ T cells by elderly human B cells (Figure 5E) and 4-1BBL+ B cells from auto-HSCT patients with breast cancer (Pat #1-B; Figure 4E). Conversely, the presence of agonistic 4-1BB Ab significantly increased induction of human GrB+CD8+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 Ab (supplemental Figure 5D).

4BL cells, present in young subjects, accumulate with old age and induce GrB+CD8+ cells requiring 4-1BBL/4-1BB axis. (A) Antagonist anti-4-1BBL (α4-1BBL), but not isotype control Ab, abrogates the ability of old-mouse B cells (Old-B) to induce GrB in young-mouse CD8+ T cells in vitro. (B-C) As such, anti-4-1BBL Ab blocks the antitumor benefit of old-mouse B cells. (B) μMT mice with B16 melanoma were adoptively transferred with naïve mouse B cells (μMT + Young-B) or B cells from old mice pretreated with either anti-4-1BBL Ab (μMT + Old-B + α4-1BBL) or control Ab (μMT + Old-B + IgG). (C) WT C57BL/C old mice with B16 melanoma were i.p. injected (at days 1, 4, 8, and 11) with anti-4-1BBL Ab (Old-α41BBL) or control Ab (Old-IgG). At day 13 post–tumor challenge, the anti-4-1BBL Ab–injected old mice were also divided into 2 groups, and one group received adoptive transfer of B cells from syngeneic naïve old mice (Old-α41BBL + Old-B). Shown are mean tumor size (mm2, Bi, C) and tumor weight (g, Bii) ± SEM of a 4 to 5-mice-per-group experiment repeated 3 times. (D) Old-mouse B cells cannot induce GrB expression in 4-1BB–deficient CD8+ T cells (4-1BB KO). Shown are mean ± SEM (GrB, %) within proliferating CD8+ T cells of WT or congenic 4-1BB KO mice. (E) Antagonistic 4-1BB Ab, but not control Ab, blocks human GrB expression in CD8+ T cells induced by old human B cells. This is shown as a fold change (mean ± SEM) of GrB+CD8+ cells induced with B cells of young people (dotted line). (F) To demonstrate the presence of 4BL cells in young people, 4-1BBL+ B cells were sort-purified (>90%) and used to stimulate GrB (mean ± SEM) in proliferating CD8+ T cells in triplicate experiments reproduced independently 4 times.

4BL cells, present in young subjects, accumulate with old age and induce GrB+CD8+ cells requiring 4-1BBL/4-1BB axis. (A) Antagonist anti-4-1BBL (α4-1BBL), but not isotype control Ab, abrogates the ability of old-mouse B cells (Old-B) to induce GrB in young-mouse CD8+ T cells in vitro. (B-C) As such, anti-4-1BBL Ab blocks the antitumor benefit of old-mouse B cells. (B) μMT mice with B16 melanoma were adoptively transferred with naïve mouse B cells (μMT + Young-B) or B cells from old mice pretreated with either anti-4-1BBL Ab (μMT + Old-B + α4-1BBL) or control Ab (μMT + Old-B + IgG). (C) WT C57BL/C old mice with B16 melanoma were i.p. injected (at days 1, 4, 8, and 11) with anti-4-1BBL Ab (Old-α41BBL) or control Ab (Old-IgG). At day 13 post–tumor challenge, the anti-4-1BBL Ab–injected old mice were also divided into 2 groups, and one group received adoptive transfer of B cells from syngeneic naïve old mice (Old-α41BBL + Old-B). Shown are mean tumor size (mm2, Bi, C) and tumor weight (g, Bii) ± SEM of a 4 to 5-mice-per-group experiment repeated 3 times. (D) Old-mouse B cells cannot induce GrB expression in 4-1BB–deficient CD8+ T cells (4-1BB KO). Shown are mean ± SEM (GrB, %) within proliferating CD8+ T cells of WT or congenic 4-1BB KO mice. (E) Antagonistic 4-1BB Ab, but not control Ab, blocks human GrB expression in CD8+ T cells induced by old human B cells. This is shown as a fold change (mean ± SEM) of GrB+CD8+ cells induced with B cells of young people (dotted line). (F) To demonstrate the presence of 4BL cells in young people, 4-1BBL+ B cells were sort-purified (>90%) and used to stimulate GrB (mean ± SEM) in proliferating CD8+ T cells in triplicate experiments reproduced independently 4 times.

The 4BL cells appears to present in young subjects, because 4-1BBL+ B cells were reproducibly detected in young mammals (albeit at low levels, <6%; Figure 1B) and thereby could be responsible for “background” levels of GrB induction in CD8+ T cells. This most likely explains why the GrB induction with young-subject B cells was also inhibited if 4-1BBL/4-1BB axis was blocked (Figure 4E and Figure 5A,E). To test this possibility, we sort-enriched 4-1BBL+ B cells from young humans (>90% enrichment) and found that they phenotypically resembled the 4BL cells of old humans. Importantly, the sorted 4-1BBL+ B cells readily and strongly induced GrB+CD8+ T cells compared with total B cells and B cells depleted of 4-1BBL cells (total B and 4-1BBL– B; Figure 5F). Taken together, the aging of mammals is associated with the accumulation of 4BL cells that induce effector GrB+CD8+ T cells using the 4-1BBL/4-1BB axis.

Discussion

Here we report previously unknown 4-1BBL+ CD86HighHLA-IHigh HLA-DRLow CD40Low CD27+CD19+ B cells (4BL cells) that accumulate in the aging of mammals, such as humans, rhesus macaques, and mice. 4BL cells are also present in young subjects, albeit in low numbers. The functional and phenotypic differences between young- and old-subject B cells was lost if we sort-enriched 4BL cells from young people. Based on their surface markers (CD27+ MHC classIHighCD86High), it is tempting to speculate that they belong to antigen-experienced memory B cells that acquired a preference for endogenous and self-antigens4 as a result of a lifelong or chemotherapy-induced exposure to damaged tissues and senescent cells,40 or from CMV infection.41 Although the mechanism of their activation is a topic for a different study, the accumulation of 4BL cells does not appear to be intrinsic to aging but rather is an induced state. First, despite the restoration of B-cell compartment in Old-restored mice, we failed to detect accumulation of 4BL cells. Second, we recently generated functionally similar 4-1BBL+ B cells by stimulating tumor-evoked Bregs with TLR9 ligands.21

As a consequence, the 4BL cells are responsible for the induction/accumulation of GrB+CD8+ T cells in old mammals, including highly differentiated GrB+CD8+CD28Low T cells found in elderly humans,10 and in lymphopenic patients after high-dose chemotherapy and auto-HSCT.20,42 The induction required TCR engagement and costimulatory molecules, which probably benefited by 4BL cells being MHC classIHigh and CD86High. In the absence of cognate antigen (gp100) or TCR stimulation, or if CD86 or CD80 is blocked, 4BL cells failed to activate CD8+ T cells. Moreover, confirming the importance of 4-1BBL,22-24 the T-cell induction also requires 4-1BBL/4-1BB axis. GrB+CD8+ T cells were not induced if 4-1BBL on 4BL cells or 4-1BB on CD8+ T cells were blocked with antagonistic antibody, or if T cells were 4-1BB–deficient. Although we do not know antigens involved in the induction of CD8+ T cells by 4BL cells, B cells are known to induce immune T-cell responses to low-antigen concentrations43 by presenting xeno and self-antigens44 captured from macrophages.45 Our modeling studies indicate that 4BL cells can induce antitumor GrB+CD8+ T cells by presenting tumor-expressed antigens in mice, including self-antigens. For example, upon adoptive transfer into tumor-bearing mice, naïve mouse 4BL cells efficiently expanded GrB+CD8+ T cells specific to melanocyte differentiation self-antigen (gp100) in the secondary lymphoid organs and in the tumor. If 4-1BBL is blocked with a respective antagonistic antibody or if 4BL cells were lost after B-cell rejuvenation with anti-CD20 Ab, the GrB+CD8+ T cell activation/expansion was not elicited in old mice, promoting faster melanoma growth. Thus, by inducing GrB+CD8+ T cells, 4BL cells inhibit the growth of poorly immunogenic B16 melanoma cells in old mice, suggesting that, at least in part, 4BL cells may also be responsible for a paradoxical aging-associated reduced growth of some tumors in mice and humans.27-29 Alternatively, these results raise an interesting possibility that 4BL cells may also participate in accumulation of CD8+ CD28– T cells in RA, MS, and T1D17,19,46 that respond to low-threshold stimuli and secrete perforin and GrB.12,13 As in Old-depleted and Old-restored mice, which lost activated CD8+ T cells and could not retard tumor growth after 4BL depletion, depletion of B cells also impairs antigen-specific T-cell activation25 and ameliorates RA, MS, and T1D.26 Furthermore, the role of 4BL cells in chronic virus-associated accumulation of CD8+CD28Low T cells in humans18,47-49 cannot be ruled out. Similar involvement in the development of autoimmunity, but via production of autoreactive antibody, was proposed for CD11c+ CD21– and MHC class IIHigh ABCs accumulated in old mice.6 However, 4BL cells appear to act primarily on CD8+ T cells and phenotypically differ by being CD21+ and MHC classIILow. Being CD40Low and MHC classIILow, they presumably will not affect CD4+ T cells or receive sufficient CD40/CD40L signaling from CD4+ T-cell helper cells and CD28–CD8+ T cells.13 Phenotypically and functionally, 4BL cells differ from potentially anergic and refractory-to-activation CD21–CD23– B cells, ABCs that also accumulate in old mice.6,7 ABCs remained almost unchanged in Old-restored mice, whereas 4BL cells (and their downstream functions) were lost and did not recover after B-cell rejuvenation of old mice. In addition, unlike 4BL cells, purified ABCs could not efficiently induce GrB+CD8+ T cells in vitro. 4BL cells probably do not control the IFNγ+CD8+CD28Low cells also reported in the elderly,35 and indeed we failed to both detect their aging-associated enrichment in mammals or induce them after in vitro stimulation with 4BL cells.

Our data raise an interesting possibility that, as important inducers of auto-reactive GrB+CD8+ T cells, 4BL cells may in fact be an immune-based risk factor for mortality and morbidity in the elderly usually associated with CD28LowCD8+ T cells.18,19,50 Alternatively, as mediators that can reduce the growth and metastasis of some cancers in the elderly,27-29,37,38 4BL cells are important immunotherapeutic targets to boost antitumor immune responses. The induction of 4-1BBL+ B cells can abrogate the metastasis of highly aggressive breast cancer in mice.21 Conversely, inactivation of 4BL cells or their 4-1BBL signaling may reverse CD8+ T cell–associated immune risk for older people. It may also improve retarded responses to vaccines by reconstituted B cells36 and by eliminating a competing source of insufficient CD40/CD40L signaling from CD28–CD8+ T cells.13

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Linda Zukley (NIA/NIH) and Jeremy Rose (NCI) for help with human blood samples, and Kelli Vaughan (NIA/SoBran, Inc.) for providing Rhesus macaque blood, and Ana Lustig and Drs Dan Longo (NIA/NIH) and Edward Goetzl (University of California-San Francisco and NIA) for helpful comments.

This research was supported by the NIH, Intramural Research Program of the NIA.

Authorship

Contribution: C.L.-C., M.B., K.M., P.B.O., and P.J.H. performed the research; A.C.C., M.C., J.A.M., R.E.G., L.F., and F.H. contributed to vital new reagents; C.L.-C., M.B., F.H., and A.B. analyzed and interpreted the results; A.B. and C.L.-C. wrote the paper; and A.B. conceived, designed, and supervised the research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Arya Biragyn, National Institute on Aging, 251 Bayview Blvd, Suite 100, Baltimore, MD 21224; e-mail: biragyna@mail.nih.gov.

![Figure 1. The elderly accumulate GrB+CD8+ T cells and 4-1BBL+ B cells. (A-B) Proportions of CD28Low/- (i) and GrB+-expressing CD8+ T cells (ii) and for 4-1BBL+ B cells (B) are increased in the elderly (Old, n = 28), compared with the young (Young, n = 18). Shown are CD28 (i, a representative histogram) and GrB (ii, mean ± SEM) expressions in gated PB CD8+ T cells, and a representative dot plot (%; B, upper panel) and a summary whiskers-and-box plot (Student t test P = .009, Mann-Whitney U test P = .008, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P = .003; B, lower panel) of 4-1BBL in gated CD19+ B cells. (C) The 4-1BBL+ B cells in old human donors (black line) also are CD27+ CD40+ CD86High HLA-IHigh but HLA-DRLow, compared with the 4-1BBL– B cells (dotted line). (D-F) 4-1BBL+CD19+ B cells were enriched in some patients with inflammatory breast cancer after auto-HSCT (n = 11, D). 4-1BBL+ CD19+ B cells (gated in CD19+ cells, D) were enriched above the 6% level of arbitrary threshold set for healthy donors. The samples were also enriched for GrB+CD28LowCD8+ T cells (mean ± SEM [E-F]). *P < .05 was considered significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/124/9/10.1182_blood-2014-03-563940/4/m_1450f1.jpeg?Expires=1769085216&Signature=mvnzaCCvFQ9yZBmWVvYvNQjbkAKF4rrcdlpb~gbiECagPFy1yDjfdk5do2fBSVFA5cwHqMcgHdnQz~iTeGSyoK2oxwFNTfgnlXvdylTYLOrGtcEBI4qZCMZ0wrkmtLlVRZn9F~S3BCH6Z0P0O6zLFZ2uF8Z2O03TQyRWJ94UjbB8WYJtfu05svN5mdQ~Kjd9qChpCUxB3bI8IQACoTsTke5m4w~UeIwZ9hCqBVL1Hg-qjlyvZ9O6-2NhlykztjsxkkefNc9Y4PBPfwqBuDCKaMs5ZGeuBwZbiFZMr-Os2qK1zJwPEkOUTUudzWustSHwV00c~jVdcQiJ3kSKD8kfOQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. The elderly accumulate GrB+CD8+ T cells and 4-1BBL+ B cells. (A-B) Proportions of CD28Low/- (i) and GrB+-expressing CD8+ T cells (ii) and for 4-1BBL+ B cells (B) are increased in the elderly (Old, n = 28), compared with the young (Young, n = 18). Shown are CD28 (i, a representative histogram) and GrB (ii, mean ± SEM) expressions in gated PB CD8+ T cells, and a representative dot plot (%; B, upper panel) and a summary whiskers-and-box plot (Student t test P = .009, Mann-Whitney U test P = .008, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P = .003; B, lower panel) of 4-1BBL in gated CD19+ B cells. (C) The 4-1BBL+ B cells in old human donors (black line) also are CD27+ CD40+ CD86High HLA-IHigh but HLA-DRLow, compared with the 4-1BBL– B cells (dotted line). (D-F) 4-1BBL+CD19+ B cells were enriched in some patients with inflammatory breast cancer after auto-HSCT (n = 11, D). 4-1BBL+ CD19+ B cells (gated in CD19+ cells, D) were enriched above the 6% level of arbitrary threshold set for healthy donors. The samples were also enriched for GrB+CD28LowCD8+ T cells (mean ± SEM [E-F]). *P < .05 was considered significant.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/124/9/10.1182_blood-2014-03-563940/4/m_1450f1.jpeg?Expires=1769190011&Signature=oB1Ej-oQsVpiziEGfdmT~t0vM02VmkS1IVkZj7ZDnxaiR5EJ7km2UCtsp6G1QU3M0VUQPqBmj8HqJBu7A5cm3bsdUkB~9cUu17PaClYIxqPyebj4BpXLdmusrOVv9b08jK9guUojFvraxtUsy-RkmvVd0HJY0IphxCzo9AYEuFpz3ktfdzjsC1d0j3APCPWfTZP1eTpU4NH8vUXahz-UrzeXnjCoWBcpPkbG3X2zKH~pu-pOKzv3j2Aa7HMocFUXXSvbSndjS9gNFuGAt6x35wR2QFvEaKzLuJ2CL6yZjv2AGUzcyTUlYV-f0sH3qLPwhtx7lZPN-oNZ1a1xKxs83Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)