Key Points

ONTAK blocks DC maturation by coreceptor downmodulation and inhibition of Stat3 phosphorylation to induce a tolerogenic phenotype.

ONTAK kills activated CD4 T cells but stimulates antiapoptosis in resting Treg by engagement and stimulation through CD25.

Abstract

Denileukin diftitox (DD), a diphtheria toxin fragment IL-2 fusion protein, is thought to target and kill CD25+ cells. It is approved for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is used experimentally for the depletion of regulatory T cells (Treg) in cancer trials. Curiously enough, clinical effects of DD did not strictly correlate with CD25 expression, and Treg depletion was not confirmed unambiguously. Here, we report that patients with melanoma receiving DD immediately before a dendritic cell (DC) vaccine failed to develop a tumor-antigen–specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell immune response even after repeated vaccinations. Analyzing the underlying mechanism, so far we found unknown effects of DD. First, DD modulated DCs toward tolerance by downregulating costimulatory receptors such as CD83 and CD25 while upregulating tolerance-associated proteins/pathways including Stat-3, β-catenin, and class II transactivator–dependent antigen presentation. Second, DD blocked Stat3 phosphorylation in maturing DCs. Third, only activated, but not resting, Treg internalized DD and were killed. Conversely, resting Treg showed increased survival because of DD-mediated antiapoptotic IL-2 signaling. We conclude that DD exerts functions beyond CD25+ cell killing that may affect their clinical use and could be tested for novel indications. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov, #NCT00056134.

Introduction

A series of clinical trials using ex vivo–generated dendritic cell (DC) vaccines has yielded promising results in the treatment of cancer.1-3 It is assumed that at least 3 parameters define the clinical efficacy of the anti-tumor response, namely (1) the quantity and quality of the induced immune response; (2) the resistance in the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment; and (3) the amplitude of the regulatory T-cell (Treg) response. Tregs are believed to suppress T-cell immunity and thus could be an important obstacle to cancer immunotherapy.4

Several strategies are currently being explored to achieve Treg depletion in patients, including anti-CD25 antibodies and immunotoxins such as denileukin diftitox (DD).4 The diphtheria toxin fragment IL-2 fusion protein DD (ONTAK) is assumed to bind the high-affinity (α−β−γ) IL-2R and induce its rapid internalization. Within endocytic vesicles, low pH leads to cleavage of the catalytic domain, liberating the toxin into the cytosol where protein synthesis is blocked by adenosine 5′-diphosphate ribosylation of elongation factor 2. Inhibition of protein translation eventually leads to cell death through apoptosis and occurs after 40 to 72 hours.5-7 To date, DD has been used for Treg depletion in 7 cancer trials8-14 using different doses (5, 12, and 18 μg/kg/day) and treatment cycles. In 4 trials, treatment was followed by vaccination with tumor-associated antigen (TAA)–loaded DCs directed against melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and carcinoembryonic antigen–positive cancer (colorectal and breast). Whereas 4 reports found a lasting (up to 56 days) Treg depletion of 40% to 60%,8-10,13 1 study found only a transient decrease,12 and 2 studies found no changes.11,14 Furthermore, a definite evidence for a clinical benefit has not yet been presented.

In a clinical trial using a DC cancer vaccine against melanoma, we pretreated patients with DD to deplete Treg and enhance the vaccine response. The immunological and clinical results were unexpected and prompted us to investigate in detail effects of DD in patients and in vitro. Surprisingly, we found that DD affected the function of DC inducing a tolerogenic phenotype. We conclude that DD may exert functions beyond cell killing that should be considered when used for treatment of patients.

Materials and methods

Clinical trial and study design, generation of DC vaccine, immunomonitoring, cell sorting, and bioinformatic analysis are detailed in the supplemental Materials and methods available on the Blood Web site.

Generation of cells and reagents

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy volunteers were obtained after approval by the local ethics committee and informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Monocyte-derived DCs were generated from PBMCs as described previously,15 using granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor and IL-4 (6 days) to generate immature DCs (imDC), and a maturation cocktail (IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and prostaglandin E2) to obtain mature DCs (maDC) on day 7 (IL-4 was also from Strathmann, and IL-1β came from ACM-Biotech GmbH). CD4+ or CD4+ CD25− effector T cells (Teff) and CD4+ CD25+ (Treg) T cells were isolated by magnetic-activated cell-sorting kits (Miltenyi Biotec) resulting in a T-cell enrichment of >85% Teff and >90% Treg. DD was purchased as ONTAK from Seragen, Inc, and recombinant human IL-2 from R&D Systems.

Flow cytometry analysis, antibodies, and cell sorting

Antibodies and a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) were used. For analysis of DC subsets in blood, the DC enumeration kit (Miltenyi Biotec; #130-091-086) was used according to the procedures of the manufacturer. To stain additional PBMC subsets, the following antibodies were used: CD3 (UCHT1), CD4 (RPA-T4), CD8 (HIT8a), CD14 (M5E2), CD15 (HI98), CD16 (3G8), CD19 (HIB19), CD45 (2D1), and CD56 (B159) (BD Biosciences). Treg were determined from frozen PBMCs (1 time point for all samples) and were defined as CD25++FoxP3+CD127(+)/CD3+CD4+. Intracellular staining of Foxp3 was performed by using the staining kit (PCH101) from NatuTec. In addition, the directly fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for surface staining of CD25 (2A3), intracellular phosphoSTAT5 (pY694), and Bcl-2 (Bcl-2/100) were from BD Pharmingen. The active form of Caspase3 (C92-605) was measured by using the apoptosis kit from BD Pharmingen. Apoptosis was measured by annexin-V binding using the detection kit of BenderMed Systems. The binding of DD to T cells was detected by an anti-diphtheria toxin antibody (Ab Serotec). For acidic washes, samples were then washed with 200 mM of acidic acid containing 0.5 M of sodium chloride at pH = 2 (Merck) for 1 minute at 4°C or 37°C to remove loosely bound DD. Then cells were washed twice with a large volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before flow cytometric analysis. Samples were analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer using Cell Quest analysis software (BD Pharmingen).

T-cell proliferation and suppression assays

To stimulate T-cell proliferation, round-bottom 96-well plates were coated overnight at 4°C with anti-CD3 (OKT3 at 10 µg/mL; BD). T cells were seeded in triplicate cultures at 1 × 105 T cells per well, and soluble anti-CD28 (10 µg/mL; BD) was added. In some experiments, allogeneic 1 × 104 maDC pretreated with the indicated concentrations of DD (24 hours), or left untreated, were used to stimulate T cells. To assess T-cell suppression, CD4+CD25− responder and CD4+CD25+ Treg were isolated as described above. Both cell subsets were plated alone or as a 1:1 mixture at 1 × 105 cells per well in round-bottom 96-well plates in triplicates. To measure proliferation, cells were incubated for 3 or 5 days as indicated and then were pulsed with 37 kBq per well [3H]thymidine (Amersham) for 16 hours, followed by harvesting on filters (using a 96-well harvester; Tomtec) and counting in a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta TriLux counter (PerkinElmer).

Confocal microscopy

For detection of DD uptake into T cells, CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells were isolated as described above and were left untreated or were stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin for 4 to 16 hours. Then the cells were either treated or not treated for 4 hours with various concentrations of DD as indicated. Cytospin preparations were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, 2 mM of MgCl2, and 0.2% glutaraldehyde and stained with a mouse-anti-diphtheria toxin antibody (AbD Serotec; clone 7F2, 20 µg/mL, 1 hour), washed with PBS, and detected with an ALEXAFluor 555-conjugated goat-anti-mouse antibody (Invitrogen; 4 µg/mL, 1 hour). Slides were repeatedly washed in PBS, dried and mounted with Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech), and analyzed in a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Laser Scanning system [LSM 510 Meta; Zeiss]) based on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 200 M; Zeiss). All of the procedures were performed at room temperature.

Multi-epitope ligand cartography (MELC) technology

The MELC technology has been described previously.16 Briefly, a slide with a tissue specimen was placed on an inverted wide-field fluorescence microscope (Leica) fitted with fluorescence filters for fluorescein isothiocyanate and phycoerythrin. Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies and wash solutions were added and removed robotically under temperature control, avoiding any displacement of the sample and objective. In each staining cycle, an antibody was added; phase-contrast and fluorescence images were recorded by a high-sensitivity cooled charge-coupled device camera; the sample was washed with PBS and bleached at the excitation wavelengths. Data acquisition was fully automated.

Results

DD impairs the induction of vaccine-specific T-cell responses

To deplete their Treg before DC vaccination, patients with chemotherapy-resistant stage IV cutaneous melanoma (16 individuals, cohort 1) were treated with DD (5 μg/kg) on 3 consecutive days followed per protocol by 4 cycles of a DC vaccine during a period of 10 weeks (Figure 1A, cohort 1 of trial, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00056134). Before the first evaluation (week 16), 9 (56%) of the 16 patients had to be excluded from the trial because of disease progression, whereas only 2 (12%) of 17 individuals were excluded in a clinical stage-matched control group receiving the same DC vaccine without DD pretreatment (clinical trial NCT00053391, manuscript in preparation [Andreas Baur, Thomas G. Berger, Michael Erdmann, Thomas F. Gajewski, Stefanie Gross, Ina Haendle, Gerold Schuler, Erwin Shultz, Beatrice Schuler-Thurner, Steve Voland, Yuanyuan Zha]).

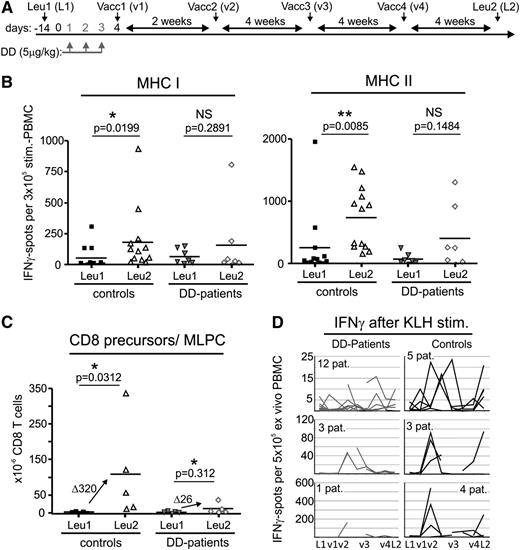

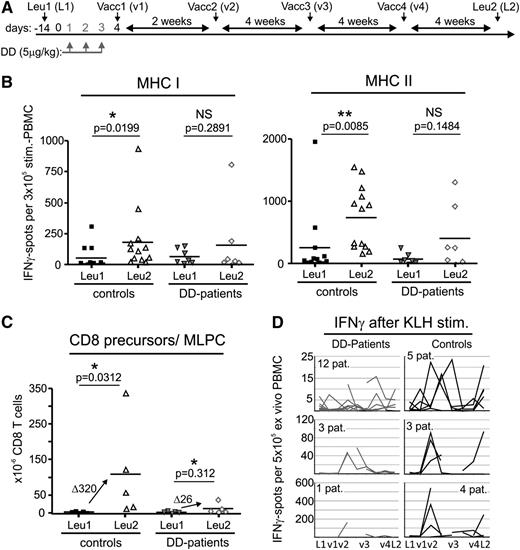

DC-vaccinated patients with melanoma pretreated with DD have a reduced immune response against the tumor vaccine and a lowered IFNγ response to KLH. (A) DD pretreatment and DC vaccination scheme. Ontak (DD) was given to patients intravenously on 3 consecutive days (days 1-3). On day 4, the first of 4 DC vaccine aliquots (v1-v4) was injected intracutaneously. The remaining aliquots were administered as indicated (every 2-4 weeks). Immunomonitoring was performed with TAA-prestimulated PBMC at Leu1 (L1) and Leu2 (L2) (see panels B-C). Additional monitoring was performed ex vivo with KLH at Leu1 (L1), times of vaccination (v1-v4), and Leu2 (L2) (see panel D). Vacc (vaccination), Leu (leucapheresis). (B) IFNγ EliSpots of peptide-prestimulated PBMC (see “Materials and methods”) against vaccinated TAA after 4 vaccinations (Leu2) compared with Leu1 (prevaccination) assessed separately for MHC class I and II peptides; Note that only those patients reaching Leu2 and able to provide sufficient PBMC could be included. The statistical analysis is based on the paired Student t test, 1-tailed, followed by the Wilcoxon signed rank-sum test. Lines in the scatterplots represent the median of all values. (C) Increase of CD8+ T-cell precursors in DD patients and control patients as measured by MLPC limiting dilution after 4 vaccinations. Statistical analysis is as in (B); lines in the scatterplot represent the median of respective values. The increase of spots is expressed as Δ median values. Note that only those patients able to provide enough PBMC at Leu2 could be included. (D) Number of IFNγ ex vivo KLH-specific EliSpots (broken up into 3 groups based on the number of EliSpots) assessed during the course of 4 vaccinations for 16 DD-pretreated patients and 12 control patients at indicated time points if PBMC were available.

DC-vaccinated patients with melanoma pretreated with DD have a reduced immune response against the tumor vaccine and a lowered IFNγ response to KLH. (A) DD pretreatment and DC vaccination scheme. Ontak (DD) was given to patients intravenously on 3 consecutive days (days 1-3). On day 4, the first of 4 DC vaccine aliquots (v1-v4) was injected intracutaneously. The remaining aliquots were administered as indicated (every 2-4 weeks). Immunomonitoring was performed with TAA-prestimulated PBMC at Leu1 (L1) and Leu2 (L2) (see panels B-C). Additional monitoring was performed ex vivo with KLH at Leu1 (L1), times of vaccination (v1-v4), and Leu2 (L2) (see panel D). Vacc (vaccination), Leu (leucapheresis). (B) IFNγ EliSpots of peptide-prestimulated PBMC (see “Materials and methods”) against vaccinated TAA after 4 vaccinations (Leu2) compared with Leu1 (prevaccination) assessed separately for MHC class I and II peptides; Note that only those patients reaching Leu2 and able to provide sufficient PBMC could be included. The statistical analysis is based on the paired Student t test, 1-tailed, followed by the Wilcoxon signed rank-sum test. Lines in the scatterplots represent the median of all values. (C) Increase of CD8+ T-cell precursors in DD patients and control patients as measured by MLPC limiting dilution after 4 vaccinations. Statistical analysis is as in (B); lines in the scatterplot represent the median of respective values. The increase of spots is expressed as Δ median values. Note that only those patients able to provide enough PBMC at Leu2 could be included. (D) Number of IFNγ ex vivo KLH-specific EliSpots (broken up into 3 groups based on the number of EliSpots) assessed during the course of 4 vaccinations for 16 DD-pretreated patients and 12 control patients at indicated time points if PBMC were available.

For fully evaluable patients (no disease progression and able to provide PBMCs for immune assays), the immune response to TAA was assessed before and after 4 cycles of DC vaccination (week 16) by EliSpot analysis and mixed lymphocyte peptide culture (MLPC). DD-pretreated patients reaching evaluation 1 (7 individuals [44%], week 16) showed no or only a minor or low increase in interferon-γ (IFNγ)–producing cells (Figure 1B, compare Leu1 with Leu2). This was in contrast to the control group (12 participants), who developed the expected bivalent (class I and II) increase of anti-TAA immune responses that was statistically significant. Likewise, an increase of TAA CD8+ T cells was only observed in the control group (MLPC; Figure 1C) and was almost completely lacking in the DD-pretreated patients, with the exception of one patient.

Trying to explain these unexpected results, we first assumed that the projected Treg depletion did not occur. An initial Treg analysis using FACS and Foxp3 quantitative polymerase chain reaction confirmed this assumption.17 However, the almost complete lack of a vaccine effect even after multiple vaccinations raised suspicion that a DC-mediated tolerization event had occurred, potentially by the DD pretreatment influencing the first vaccination cycle. Supporting this assumption, PBMCs of DD-treated patients did not develop the expected IFN-γ response to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH). For internal control, a DC aliquot of the first vaccination cycle had been loaded with KLH before injection. Subsequently, a KLH-specific EliSpot was performed at every vaccination cycle (Figure 1D) to validate the immunization procedure. Although PBMCs of the control group secreted IFN-γ in a distinct pattern peaking between Vac1 and Vac3 and at Leu-2 (Figure 1D, right), the response in DD patients was greatly reduced or was absent (Figure 1D, left).

The seemingly inferior vaccine response in DD-pretreated patients could have been caused by a sampling error within the nonrandomized small study design. Nevertheless, we stopped the trial after 23 patients and, for clarification, analyzed DD-treated DCs and Treg in more detail.

DD affects DCs in vivo and alters their function in vitro

Assuming that DD could have influenced preexisting DCs in vivo and/or injected vaccine DCs, we first analyzed relative levels of all major DC subsets (mDC1 [BDCA1, CD1c+], mDC2 [BDCA3, CD141+], and pDC [BDCA2,CD303+])18 in blood and compared them with those obtained for CD4 and Treg cells. The analysis was done by FACS (twice daily) in a second cohort of patients (4 patients with stage IV melanoma, referred as cohort 2) after approval by the local ethics committee. In addition, we increased DD dosage to 3 × 12 μg/kg and 1 × 18 μg/kg of DD (2 patients each dosage), assuming that higher DD doses are more effective in Treg depletion. Although there were the expected interindividual differences, all participants developed a rapid decrease of all cell subpopulations, including DCs, within 6 hours down to ∼20% of original levels (supplemental Figure 1). All subpopulations recovered quickly, sometimes overnight, and reached original levels usually within 8 days. Thus, DD affected in vivo levels of Treg, CD4+ T cells, and preexisting DCs rather similarly and in a period overlapping the first DC vaccination cycle. Therefore, it seemed possible that DD affected the function of DCs in vivo.

To assess functional differences, monocyte-derived imDC or maDC from healthy donors were treated with DD in vitro (48 hours). In doses usually reached in the patient’s serum (10-100 ng/mL),19 cell death of imDC increased by 10% to 25% but only by 2% to 5% in maDC (Figure 2A), indicating that imDC ingested DD despite a lack of IL-2R, including the IL-2R β-chain (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 2). In line with this assumption, blocking anti-CD25 antibodies (daclizumab) could not prevent DD-induced cell death of imDC (supplemental Figure 3).

DD treatment modulates DC function in vitro. (A) imDC and maDC were generated in vitro (see “Materials and methods” for details) and were incubated with increasing doses of DD (as indicated) for 48 hours. Subsequently, cells were labeled with annexin V and analyzed by FACS. Error bars (standard deviation, SD) were calculated on the basis of triplicates of 1 representative experiment (3 performed). (B) MLR using DD pretreated imDC and maDC (48 hours; 0, 10, 100, and 1000 ng/mL) and allogeneic CD4 T cells at different DC: T-cell ratios as indicated. Dead DCs were excluded by trypan blue staining. (C) MLR with DD-pretreated maDC and allogeneic CD4 T cells (1:20 ratio), supplemented with resting or activated Treg (autologous to maDC). (D) Surface levels of different receptors on maDC and imDC after DD treatment (0, 10, and 100 ng/mL) for 48 hours. Intracellular levels are shown in supplemental Figure 6. Data in (C) and (D) are shown as mean values ± standard error of 4 independent experiments using PBMC from different healthy donors. P values were calculated with the Student t test (*P < .05; **P < .01).

DD treatment modulates DC function in vitro. (A) imDC and maDC were generated in vitro (see “Materials and methods” for details) and were incubated with increasing doses of DD (as indicated) for 48 hours. Subsequently, cells were labeled with annexin V and analyzed by FACS. Error bars (standard deviation, SD) were calculated on the basis of triplicates of 1 representative experiment (3 performed). (B) MLR using DD pretreated imDC and maDC (48 hours; 0, 10, 100, and 1000 ng/mL) and allogeneic CD4 T cells at different DC: T-cell ratios as indicated. Dead DCs were excluded by trypan blue staining. (C) MLR with DD-pretreated maDC and allogeneic CD4 T cells (1:20 ratio), supplemented with resting or activated Treg (autologous to maDC). (D) Surface levels of different receptors on maDC and imDC after DD treatment (0, 10, and 100 ng/mL) for 48 hours. Intracellular levels are shown in supplemental Figure 6. Data in (C) and (D) are shown as mean values ± standard error of 4 independent experiments using PBMC from different healthy donors. P values were calculated with the Student t test (*P < .05; **P < .01).

In mixed-leukocyte reaction (MLR) experiments, DD-pretreated maDC (48 hours) revealed a greatly reduced capacity to stimulate T-cell proliferation. This depended on the DD preincubation dosage and the DC:T-cell ratio (Figure 2B). Essentially, DD could suppress cell proliferation to levels seen in MLRs with imDC (Figure 2B, upper graph). As expected, the effect was far more potent when DD was present in the allogeneic MLR culture (supplemental Figure 4). This was likely the result of toxic DD effects on proliferating T cells (see below). In MLR experiments supplemented with Treg (autologous to the maDC used), DD pretreatment of maDC seemingly increased the Treg suppressive capacity (Figure 2C). However, this was likely due to a failure of those DCs to stimulate T-cell proliferation (see also Figure 3) and not due to stimulating effects of DD on Treg (supplemental Figure 5).

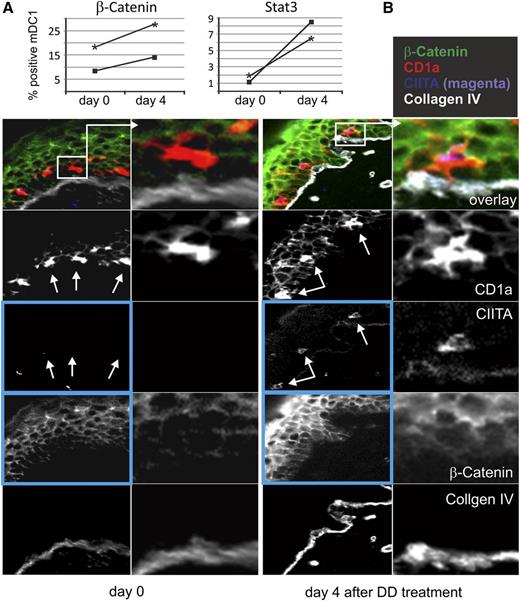

DD treatment induces increased expression of β-catenin and CIITA in skin tissue (see also supplemental Figure 8). (A) PBMC from patients #19 and #21 (3 × 12 μg/kg; see also supplemental Figure 1) were stained for intracellular β-catenin and Stat-3 on day 0 and day 4 after DD treatment, and mDC1 were analyzed by FACS. (B) Tissue sections (cryosections) of healthy skin obtained from patient #19 (see results for patient #21 in supplemental Figure 8) on day 0 and day 4 were stained side by side using MELC robots as described previously16 and the indicated directly labeled fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated antibodies. Digital images were obtained at 20-fold magnification. The main differences are seen in the expression levels of CIITA and β-catenin (blue boxed images, details in text). White arrows depict epidermal Langerhans cells not expressing (day 0) or expressing CIITA (day 4). β-Catenin showed enhanced expression on day 4; note the appearance of the protein in the cytoplasm of skin cells. Pixel intensities of images of the same tissue section, representing expression levels of proteins, were adjusted relative to the expression level of collagen IV, which served as a control.

DD treatment induces increased expression of β-catenin and CIITA in skin tissue (see also supplemental Figure 8). (A) PBMC from patients #19 and #21 (3 × 12 μg/kg; see also supplemental Figure 1) were stained for intracellular β-catenin and Stat-3 on day 0 and day 4 after DD treatment, and mDC1 were analyzed by FACS. (B) Tissue sections (cryosections) of healthy skin obtained from patient #19 (see results for patient #21 in supplemental Figure 8) on day 0 and day 4 were stained side by side using MELC robots as described previously16 and the indicated directly labeled fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated antibodies. Digital images were obtained at 20-fold magnification. The main differences are seen in the expression levels of CIITA and β-catenin (blue boxed images, details in text). White arrows depict epidermal Langerhans cells not expressing (day 0) or expressing CIITA (day 4). β-Catenin showed enhanced expression on day 4; note the appearance of the protein in the cytoplasm of skin cells. Pixel intensities of images of the same tissue section, representing expression levels of proteins, were adjusted relative to the expression level of collagen IV, which served as a control.

Searching to explain the block in T-cell proliferation, we found a significant decrease in surface and intracellular levels of CD83 and CD25, predominantly with maDC (4 experiments). Other coreceptors, including CD80 and CD70, showed a trend in the same direction, whereas CD86, CCR7, and HLA-DR levels remained constant or slightly increased (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 6). Although different DC populations were analyzed (in vitro generated vs in vivo DCs), these experiments seemingly recapitulated DD effects seen in patients, namely, suppressing the T-cell response.

DD treatment induces upregulation of tolerogenic effectors and antigen presentation

To further assess the effects of DD on DCs, we performed messenger RNA (mRNA) array analyses on mDC1 and monocytes from patients. The cells were sorted from PBMCs of 2 patients in cohort 2 before and during DD treatment (days 0 and 2). In addition, maDC treated with DD in vitro were analyzed accordingly (supplemental Figure 7). In our analysis, we looked for genes and pathways commonly affected by DD in the different DC populations in vivo and in vitro. In addition, we analyzed factors known to play a role in DC-mediated tolerance. For comparison, existing data sets of maturing DCs were analyzed as retrieved from public sources (Array Express accession ID E-MTAB-448, lipopolysaccharide [LPS] samples).

In mDC1 and monocytes in vivo, 1369 genes were upregulated and 1292 downregulated after DD-treatment, whereas in vitro 4978 genes were upregulated and 5097 downregulated (ArrayExpress, ID E-MTAB-979 and E-MTAB-977), demonstrating that DD was not merely blocking protein translation. A consistent finding was the increase of Stat3 mRNA, a regulator of T-cell and DC tolerance,20-24 in all DD-treated DCs and monocytes in vivo and in vitro. This effect was not seen in DCs treated with a maturation cocktail (see Materials and methods), LPS, Candida, or Toll-like receptor (TLR)7/8 agonist R-848 (all after 12 hours; Table 1, and data not shown). Furthermore, antigen-presenting (HLA class I and II) and processing genes were increased including class II transactivator (CIITA), which is involved in the regulation of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) promoters. Importantly, an upregulation was not seen for coreceptor mRNA, as this would be indicative for a protective immune response and was observed in maturing DCs (Table 1). In addition, β-catenin and NOD2, factors also implicated in DC tolerance,25-27 were upregulated in mDC1. Finally, in mDC1 and maDC, we found upregulation as well as downregulation of an entire set of genes (supplemental Table 1), which are part of a signaling network that regulates natural killer–mediated cytotoxicity (details in legend of supplemental Table 1). According to topological pathway analysis,28,29 these changes would cause a block of natural killer cell cytotoxic activity.

To confirm the mRNA results on the protein level, Stat3 and β-catenin were analyzed in mDC1 of PBMCs (cohort 2) by FACS (day 0 and day 4). In accordance with the mRNA analysis, we saw an increased expression of both factors in both patients treated with 3 × 12 μg/kg (Figure 3A). To assess DD effects in tissue, skin biopsies were analyzed by immunofluorescence on day 0 and day 4, the day the DC vaccine had been administered. We applied the robot-automated MELC technique,16 by which multiple tissue sections can be stained with multiple antibodies side by side in identical conditions. Because the Stat3 antibody was not reactive in tissue, we stained for β-catenin and CIITA. Day 0 epidermal Langerhans cells, identified by anti-CD1a, showed no CIITA expression, which, however, was strongly increased on day 4 (Figure 3B, white arrows; second patient in supplemental Figure 8). In addition, β-catenin was upregulated in Langerhans cells and in upper-layer keratinocytes (Figure 3B, green color). Seemingly, β-catenin was present in the cytoplasm of most, but not all, skin cells. Before DD treatment, the protein was seen predominantly at the plasma membrane. Taken together, our in vivo mRNA array results correlated with protein expression in mDC1 and skin.

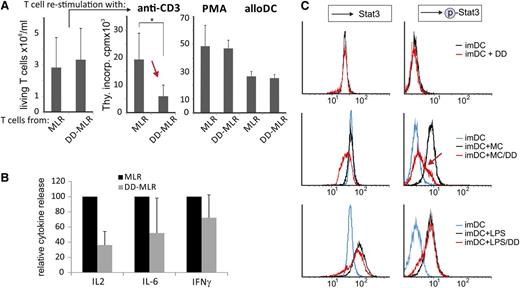

DD-treated DCs show impaired STAT3 phosphorylation and induce T-cell anergy

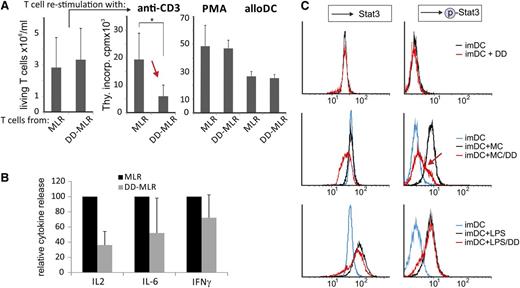

Next, we asked whether DD-pretreated DCs would induce T-cell anergy, as would be expected for a tolerogenic effect. In vitro–generated imDC were preincubated with maturation cocktail ± DD and cocultivated with allogenic CD4+ T cells. After 5 days T cells were retrieved from these MLR/DD-MLR cultures and restimulated with OKT3, PMA, or third-party allogeneic maDC. On restimulation with anti-CD3, the DD-MLR–derived T cells showed a significant defect in proliferation (Figure 4A, red arrow). This was not due to increased apoptosis, as (1) the number of live cells was comparable in controls (Figure 4A, left graph); and (2) restimulation with PMA or allogeneic DCs produced similar proliferation results for MLR and DD-MLR–derived T cells (Figure 4A, right graph). Thus, the restimulation defect was specific for allo-antigen–reactive T cells that had interacted with the DD-treated DCs. In line with this finding, the DD-MLR produced much lower IL-2 levels than the control MLR, and a trend for lower production of IL-6 and IFN-γ was also observed (Figure 4B; supplemental Table 2B). Conversely, we did not see a difference in IL-10 secretion (supplemental Table 2A).

DD-modified DCs show impaired STAT3 phosphorylation and induce T-cell anergy. (A) imDCs were incubated with maturation cocktail (MC) ± DD (100 ng/mL) for 48 hours. After washing, control maDC and DD maDC were cocultivated with allogenic CD4+ T cells (CD4:DC ratio: 66:1), referred to as MLR and DD-MLR. After 5 days, CD4+ T cells were collected from the MLR/DD-MLR cultures, and the number of live cells was determined (left bar diagram). T-cell aliquots were subsequently restimulated with anti-CD3 (OKT3; 0.1 µg/mL), PMA, or third-party allogeneic maDC (CD4:DC ratio: 66:1) for an additional 3 days, and cell proliferation was determined by overnight thymidine incorporation (Thy.incorp.) (right bar diagram). Data are shown as mean values ± SD of 4 independent experiments. P value was calculated with the Student t test (*P < .05); counts per minute (cpm). (B) Measurement of relative cytokine secretion from MLR/DD-MLR as described in panel A by cytometric bead array. Cytokine production for control MLR was set to 100%. Mean values ± SD are shown of 4 independent standardized experiments. (C) imDC were incubated with or without DD (100 ng/mL; 48 hours) (upper panels), maturation cocktail (MC) ± DD (100 ng/mL; 48 hours) (middle panels), or LPS ± DD (100 ng/mL; 48 hours) (lower panels). Subsequently, Stat3 and phosphorylated Stat3 (p-Stat3) were stained intracellularly and were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACScan). A single representative experiment of 3 is shown.

DD-modified DCs show impaired STAT3 phosphorylation and induce T-cell anergy. (A) imDCs were incubated with maturation cocktail (MC) ± DD (100 ng/mL) for 48 hours. After washing, control maDC and DD maDC were cocultivated with allogenic CD4+ T cells (CD4:DC ratio: 66:1), referred to as MLR and DD-MLR. After 5 days, CD4+ T cells were collected from the MLR/DD-MLR cultures, and the number of live cells was determined (left bar diagram). T-cell aliquots were subsequently restimulated with anti-CD3 (OKT3; 0.1 µg/mL), PMA, or third-party allogeneic maDC (CD4:DC ratio: 66:1) for an additional 3 days, and cell proliferation was determined by overnight thymidine incorporation (Thy.incorp.) (right bar diagram). Data are shown as mean values ± SD of 4 independent experiments. P value was calculated with the Student t test (*P < .05); counts per minute (cpm). (B) Measurement of relative cytokine secretion from MLR/DD-MLR as described in panel A by cytometric bead array. Cytokine production for control MLR was set to 100%. Mean values ± SD are shown of 4 independent standardized experiments. (C) imDC were incubated with or without DD (100 ng/mL; 48 hours) (upper panels), maturation cocktail (MC) ± DD (100 ng/mL; 48 hours) (middle panels), or LPS ± DD (100 ng/mL; 48 hours) (lower panels). Subsequently, Stat3 and phosphorylated Stat3 (p-Stat3) were stained intracellularly and were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACScan). A single representative experiment of 3 is shown.

To explain these findings, we searched for molecular specifics in DD-treated DCs and analyzed Stat3 protein and phosphorylation levels, as Stat3 had been linked to DC maturation.30 imDC from a healthy donor were incubated with DD alone (Figure 4C, upper panels), maturation cocktail ± DD (middle panels), or LPS ± DD (lower panels). Subsequently, Stat3 and phospho-Stat3 were assessed by FACS. DD treatment of imDC did not increase Stat3 protein levels (Figure 4C, upper left panel) or Stat3 phosphorylation (upper right panel). This seemed to contrast with results in Figure 3, showing higher Stat3+ mDC1 in DD-treated patients. The discrepancy might have been caused by differences of the DC origin (in vivo mDC1 vs in vitro imDC) and/or DD dosage and exposure time.

On maturation of imDC by the maturation cocktail, Stat3 protein levels did not increase, but phospho-Stat3 levels rose sharply (Figure 4C, middle panels). However, on the addition of DD to the maturation cocktail, Stat3 phosphorylation was almost completely blocked (right middle panel, red arrow), whereas Stat3 levels were reduced (middle left panel). Interestingly, this trend was not observed when LPS was used as a maturation stimulus. Under these conditions Stat3 protein levels strongly increased and were only slightly inhibited by DD (lower left panel). Likewise, phospho-Stat3 sharply increased, and again, this was not inhibited by DD (lower right panel). The reduced Stat3 levels were perhaps the result of increased DD-induced toxic effects under stimulating conditions (maturation cocktail and LPS). Together, these data suggested that DD blocked Stat3 phosphorylation induced by inflammatory cytokines but not by TLR4.

Low doses of DD promote CD4+ Teff and Treg survival

In contrast to some published reports,8-10,13 we had not observed a DD-dependent specific depletion of Treg in peripheral blood17 (supplemental Figure 1). On the contrary, Treg were the only cell population that rebounded particularly strong, exceeding original levels up to threefold (supplemental Figure 1). Because effects of DD on Treg might have contributed to the lacking vaccine response, we analyzed DD-treated Treg in more detail.

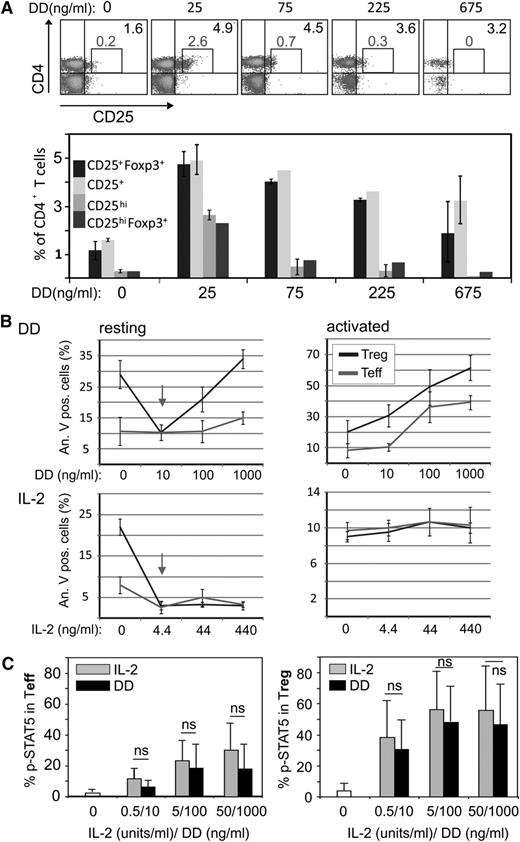

When we analyzed a PBMC bulk culture treated with increasing doses of DD for 3 days, we found that the frequency of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells rather increased, particularly at lower doses of DD (Figure 5A). Because we did not observe an increased proliferation of DD-treated Treg in vitro (supplemental Figure 5), we wondered whether the observed effect was the result of increased survival duration.

DD stimulates survival of resting Treg. (A) Resting PBMC were treated with different doses of DD as indicated for 3 days and then were analyzed by FACS. Note that the proportion of CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells increased at all DD concentrations; however, the CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ cells increased only at 25 to 75 ng/mL DD. Error bars were calculated on the basis of triplicates of 3 independent experiments. (B) (upper panels) CD4+ CD25− Teff and CD4+ CD25+ Treg, isolated from healthy donors were stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 or were left untreated and were incubated with DD for 48 hours before apoptosis was assessed by FACS (annexin-V staining). (B) (lower panels) Aliquots of the same cells were treated with equivalent doses of IL-2 (44 ng/mL of IL-2 are equivalent to 10 ng/mL of DD). The data represent mean values ± SD from 2 (upper panels) or 3 (lower panels) independent experiments. (C) Purified Teff or Treg were treated for 15 minutes with DD or IL-2 as indicated before intracellular pStat5 was assessed by FACS. The data represent mean values ± SD from 3 independent experiments.

DD stimulates survival of resting Treg. (A) Resting PBMC were treated with different doses of DD as indicated for 3 days and then were analyzed by FACS. Note that the proportion of CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells increased at all DD concentrations; however, the CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ cells increased only at 25 to 75 ng/mL DD. Error bars were calculated on the basis of triplicates of 3 independent experiments. (B) (upper panels) CD4+ CD25− Teff and CD4+ CD25+ Treg, isolated from healthy donors were stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 or were left untreated and were incubated with DD for 48 hours before apoptosis was assessed by FACS (annexin-V staining). (B) (lower panels) Aliquots of the same cells were treated with equivalent doses of IL-2 (44 ng/mL of IL-2 are equivalent to 10 ng/mL of DD). The data represent mean values ± SD from 2 (upper panels) or 3 (lower panels) independent experiments. (C) Purified Teff or Treg were treated for 15 minutes with DD or IL-2 as indicated before intracellular pStat5 was assessed by FACS. The data represent mean values ± SD from 3 independent experiments.

CD4+CD25+ (Treg) and CD4+CD25− (Teff) cells were treated with increasing DD doses. As expected,31 the activated cells died in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5B, upper right graph). Treg showed a higher susceptibility than Teff, possibly because of their constitutive CD25 expression. In contrast to a previous report,13 however, resting Treg, at low concentrations, seemed to be protected (Figure 5B, upper left graph, arrow). A comparable protective effect was seen after stimulation with equivalent amounts of IL-2 (Figure 5B, lower left graph, arrow). Together, these results implied that the IL-2 part of the fusion protein engaged CD25 and induced antiapoptotic signals, particularly at low DD doses.

To confirm this assumption, we compared Stat5 phosphorylation and caspase-3 activity in Treg after DD treatment or IL-2 stimulation. Both events are connected with increased survival (Stat5) and apoptosis (caspase-3). We found that low DD and equivalent doses of IL-2 induced Stat5 phosphorylation in a comparable fashion (Figure 5C). In line with this result, caspase-3 activity in Treg was reduced at low DD doses similar as after IL-2 stimulation (supplemental Figure 9). These data suggested that the IL-2 part of DD was functionally active and promoted cell survival.

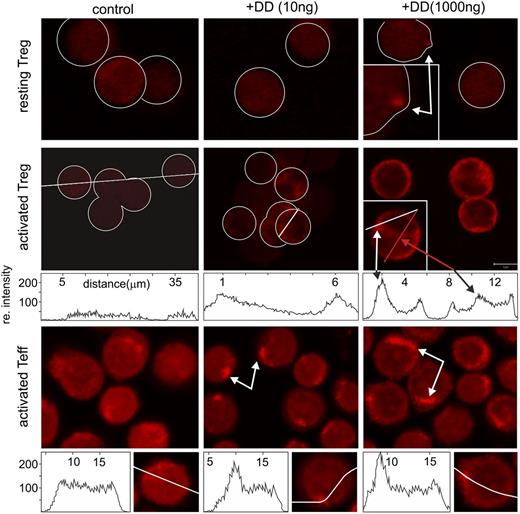

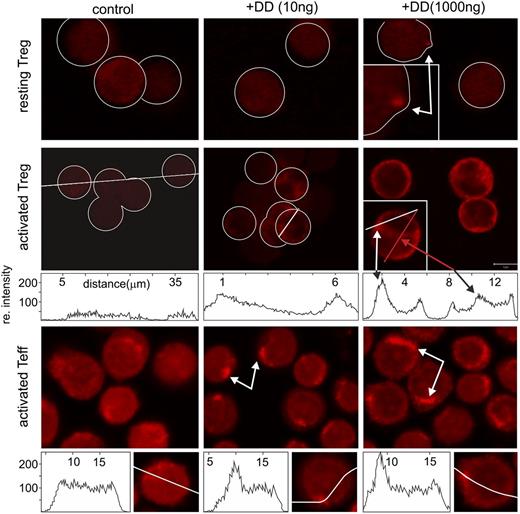

Only activated, but not resting, T cells internalize DD

So far, our findings on DD-treated Treg were in contrast to the assumption that DD is internalized on attachment and kills the target cell. Therefore, we analyzed DD attachment and internalization with resting and activated Treg/Teff. After DD incubation (16 hours), cells were stained with an anti-DD antibody and were analyzed by FACS. Only activated Treg stained for DD, whereas no firm DD binding was observed on resting Treg and Teff (supplemental Figure 10). These analyses were extended, following DD internalization via confocal imaging. Although some binding, but not internalization, of DD to resting Treg was seen at very high concentrations (1000 ng/mL) (Figure 6, upper panels, arrows), only activated Treg and Teff had internalized DD to compartments below the plasma membrane (Figure 6, middle and lower panels, arrows). These results revealed that DD could not kill resting Treg due to a lack of attachment and internalization.

DD is internalized only by activated T cells. Resting and activated Teff and Treg cells were incubated with DD (0, 10, and 1000 ng/mL; 16 hours) and stained with anti-DD. In resting Treg, only high doses of DD gave a punctual staining pattern (white arrow, upper panels). Activated Teff and Treg revealed a dose-dependent submembrane accumulation of DD (white arrows, middle and lower panels). At higher concentrations, DD was also detected in the perinuclear area (red arrow, middle panel).

DD is internalized only by activated T cells. Resting and activated Teff and Treg cells were incubated with DD (0, 10, and 1000 ng/mL; 16 hours) and stained with anti-DD. In resting Treg, only high doses of DD gave a punctual staining pattern (white arrow, upper panels). Activated Teff and Treg revealed a dose-dependent submembrane accumulation of DD (white arrows, middle and lower panels). At higher concentrations, DD was also detected in the perinuclear area (red arrow, middle panel).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that DD is not merely a death-inducing toxin but a complex immune modulator. Both parts of the fusion protein, the bacterial toxin and IL-2, seemed to be active. As demonstrated here, 2 functions of target cells have particular relevance: (1) IL-2R–independent uptake of DD by immature DCs; and (2) differential internalization of DD in resting and activated T cells.

At doses reached in the patient's serum, DD uptake by DCs, which likely occurred by macropinocytosis,32 induced a combined effect of coreceptor down-modulation, Stat3 upregulation, and increased CIITA-dependent antigen presentation. Although efficient antigen presentation favors a DC-induced T-cell response, a lack of coreceptors and the concomitant upregulation of tolerogenic effectors are expected to impair DC maturation and be tolerogenic.20,21,27,33-35 Supporting this conclusion, we observed an inhibition of Stat3 phosphorylation and induction of T-cell anergy in vitro. These findings do not prove the induction of tolerogenic DCs by DD in patients. Nevertheless, the conjunction of our in vivo and in vitro data implies that DD induces a tolerogenic DC phenotype. Because many of the DD-treated patients could not be analyzed due to disease progression, we have to assume that the in vivo effect was even more significant than presented in Figure 1.

It is well documented that some microbes developed strategies to tolerize DCs.36 A recent report showed that LcrV of Yersinia pestis targeted the pattern-recognition receptors TLR2/6 for DC tolerization.37 Another example is cholera toxin, which inhibited IL-12 production and differentiation of mouse DCs.38 Thus, some bacterial toxins may induce tolerogenic DCs under certain conditions, possibly at lower concentrations that do not overwhelm cellular clearance systems and avoid toxic effects. By this function, certain bacteria may establish a clinically healthy human carrier population; however, this is speculation at this point. In our study, DD may have acted in 2 ways. First, tissue levels of DD, which are likely lower than plasma levels, may have directly modulated the subcutaneously injected vaccine DCs. Second, vaccinated DCs, which die in significant numbers after injection, might have been cross-presented by resident DCs39 that acquired a tolerogenic phenotype by DD treatment.

The effect of DD on cells with CD25 may be different. It is assumed that every DD molecule binding to IL-2R is internalized and kills the cell. As demonstrated here, this may not be true for resting T cells. Resting T cells produce early endosomes but not the early-to-late endosome transformation necessary to unfold the toxin at low pH.40 Only activated T cells develop late endosomes,41,42 as this requires the activation of PI3 kinase.43 Signaling of DD-associated IL-2 is likely not sufficient to activate PI3 kinase; however, it may be sufficient to cause Stat5-dependent antiapoptotic effects. This mechanism may be one reason for the observed higher frequency of Treg in vivo and in vitro. The reason for the dramatic but transient decrease of all PBMC populations is unclear but could be due to DD-IL-2–induced release of chemoattractants in tissue and the known capillary leak effect of DD.

Clinical effects of DD seen in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), melanoma without vaccination, and psoriasis may support our findings. DD is particularly effective and lasting in the treatment of CTCL but less so in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.5,44,45 Persistent tumor antigen presentation by Langerhans cells is suspected to drive CTCL progression.46 It is possible that a tolerogenic phenotype induced in Langerhans cells by DD (Figure 3) is at least one reason why DD is effective in CTCL treatment. In other lymphatic malignancies, clinical benefits could be explained by the depletion of activated Teff and Treg, leading to the de novo expansion of new tumor-specific effector T cells in the absence of antigen-specific Treg. The latter has been suggested to explain the treatment benefits of DD in malignant melanoma without vaccination.12,47 DD was also reported to have beneficial effects in the treatment of psoriasis, explained by the depletion of CD3+ and CD8+ cells from skin.48 If only Treg were depleted, mixed clinical results were to be expected with some patients potentially faring worse; however, this was not the case. Again, the tolerogenic conversion of Langerhans cells by DD might have contributed to the beneficial clinical effects.

In summary, we demonstrate that DD interacts with DCs and Treg in a manner not recognized previously and exerts effects that have implications for clinical use. This raises important questions as to how and when these immunotoxins should be used for the treatment of patients with cancer. Nevertheless, our results also imply that these compounds could be valuable for antigen-specific tolerization to autoantigens or alloantigens in autoimmunity and organ transplantation, for example, in conjunction with a tolerogenic DC vaccination.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the SFB 643 “Cell Sorting and Immunomonitoring” Core Unit at the Department of Dermatology for excellent assistance.

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) via the Collaborative Research Center grant SFB 643 (Projects A9, B9, A7, C1, C2, and Z1) (A.S.B., S.S., E.Z., S.G., G.H., D.D., A.S., B.S.-T., and G.S.); BayGene (D.D.); and the TR52 (M.B.L.) (DFG). The clinical trial was primarily financed by the European Community under the Sixth Framework Programme (Cancerimmunotherapy LSHC-CT-2006-518234; DC-THERA LSHB-CT-2004-512074) (G.S. and B.S.-T.).

D.D. is a member of the “Förderkolleg” of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences.

Authorship

Contribution: A.S.B. and M.B.L. contributed equally to the experimental design and data analysis; B.S.-T. and G.S. contributed equally to the trial design and clinical supervision; G.S. was also involved in the design of the in vitro studies; S.S., G.T., E.Z., L.B., W.L., M.W., C.O., G.H., and S.G. performed the experiments; I.H., A.J.P., D.D., and A.S. helped supervise and design experiments; M.E. and E.K. helped collect and analyze patient data; L.B. and D.C. performed the bioinformatic/array analysis; all authors assisted in data analysis and figure preparation; and A.S.B. wrote and prepared the manuscript with critical comments from all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andreas S. Baur, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Erlangen, Kussmaul Campus, Hartmannstr. 14, Erlangen, 91052 Germany; email: andreas.baur@uk-erlangen.de; and Gerold Schuler, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Erlangen, INZ, Ulmenweg 18, 91054, Erlangen, Germany; e-mail: gerold.schuler@uk-erlangen.de.

References

Author notes

A.S.B. and M.B.L. contributed equally to this study.

B.S.-T. and G.S. contributed equally to this study.