Abstract

Persistently enhanced platelet activation has been characterized in polycythemia vera (PV) and essential thrombocythemia (ET) and shown to contribute to a higher risk of both arterial and venous thrombotic complications. The incidence of major bleeding complications is also somewhat higher in PV and ET than in the general population. Although its efficacy and safety was assessed in just 1 relatively small trial in PV, low-dose aspirin is currently recommended in practically all PV and ET patients. Although for most patients with a thrombosis history the benefit/risk profile of antiplatelet therapy is likely to be favorable, in those with no such history this balance will depend critically on the level of thrombotic and hemorrhagic risks of the individual patient. Recent evidence for a chemopreventive effect of low-dose aspirin may tilt the balance of benefits and harm in favor of using aspirin more broadly, but the potential for additional benefits needs regulatory scrutiny and novel treatment guidelines. A clear pharmacodynamic rationale and analytical tools are available for a personalized approach to antiplatelet therapy in ET, and an improved regimen of low-dose aspirin therapy should be tested in a properly sized randomized trial.

Introduction

Polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis are collectively classified as BCR-ABL 1–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). Chronic myeloid neoplasms share a common stem cell–derived clonal heritage of altered proliferation and differentiation, and their phenotypic diversity is attributed to differences in specific genetic rearrangements or mutation(s) that underlie the clonal myeloproliferation.1 Although considered relatively indolent diseases, MPNs are at lifelong enhanced risk of thrombosis, hemorrhage, and myelofibrotic or leukemic transformation.2-4 The aim of current therapy is to reduce the risk of thrombosis or hemorrhage in PV and ET, and to address the presenting major clinical issues in primary myelofibrosis. In particular, low-dose aspirin (81-100 mg/d), alone or in combination with phlebotomy and/or hydroxyurea, represents a consistent component of management in practically all PV and ET patients, independently of risk stratification.5,6 Inherent to these treatment recommendations are 2 distinct assumptions: (1) that the benefit/risk profile of antiplatelet therapy is consistently favorable in PV and ET, also for patients without prior thrombosis; and (2) that the same aspirin dose and dosing regimen is appropriate for both PV and ET and is comparable to that recommended in non-MPN, high-risk patients.

The aims of this perspective are to challenge these assumptions based on a critical review of the available data, to suggest a pharmacodynamic basis for individualized antiplatelet treatment, and to discuss the need for new randomized trials of antiplatelet agents in PV and ET.

Platelet activation, atherothrombosis, and venous thromboembolism

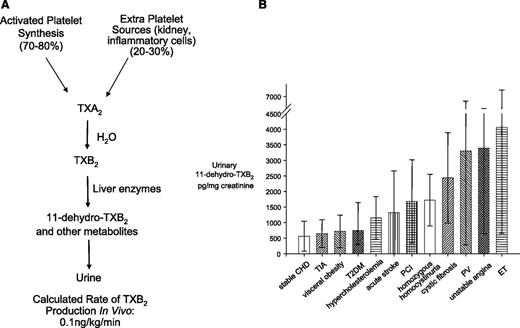

Enhanced platelet activation has been consistently demonstrated in PV and ET, by different groups and methods either in vivo7,8 or ex vivo9,10 suggesting a pathogenetic link between activated platelets and thrombotic complications. In particular, markedly enhanced urinary excretion of thromboxane (TX) A2 metabolites characterizes untreated ET and PV patients.7,8 TX metabolite excretion is a validated index of in vivo platelet activation.11 As shown in Figure 1, the urinary excretion rates of 11-dehydro-TXB2 reported in untreated ET7 and PV8 patients are at least comparable to unstable angina12 and higher than a variety of clinical settings at increased cardiovascular risk.13-19 Moreover, a role for circulating immature platelets as contributors to cardiovascular events and/or poor antiplatelet drug response has been emerging in both ET10 and non-MPN diseases.20,21 Interestingly, immature platelets are increased in ET and have been associated with a higher rate of thrombosis independently of thrombocythosis.10,22-25 Moreover, JAK2 V617F has been associated with a significantly higher number of immature platelets in ET.24,25

Rate of TXB2 production in healthy subjects (A) and urinary excretion rates of 11-dehydro-TXB2 in clinical settings at high cardiovascular risk. (A) The metabolic fate of TXA2 in vivo and the calculated rate of its production in healthy subjects on the basis of TXB2 infusions and measurement of its major urinary metabolite.11,47 (B) Mean (± standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) urinary excretion rates of 11-dehydro-TXB2 in clinical settings characterized by high cardiovascular risk.7,8,12-19 CHD, coronary heart disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Rate of TXB2 production in healthy subjects (A) and urinary excretion rates of 11-dehydro-TXB2 in clinical settings at high cardiovascular risk. (A) The metabolic fate of TXA2 in vivo and the calculated rate of its production in healthy subjects on the basis of TXB2 infusions and measurement of its major urinary metabolite.11,47 (B) Mean (± standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) urinary excretion rates of 11-dehydro-TXB2 in clinical settings characterized by high cardiovascular risk.7,8,12-19 CHD, coronary heart disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Incidence of arterial thrombosis and venous thromboembolism.

The pathophysiology and incidence of platelet-mediated microvascular disturbances in PV and ET has been reviewed elsewhere26 and will not be addressed here.

The true incidence of major arterial thrombosis (ie, fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI] and ischemic stroke) and venous thromboembolism (ie, deep vein thrombosis [DVT] or pulmonary embolism [PE]) in BCR-ABL 1–negative MPNs is difficult to estimate because of several confounding factors across different studies. Most reports included major thrombotic events together with microvascular disturbances (migraine, erythromelalgia), transient ischemic attacks (TIA), and superficial venous thrombosis. Moreover, the incidence of events is rarely expressed as percent per year, and the majority of the cohorts include patients with different cytoreductive strategies, with or without previous thrombosis and/or antiplatelet treatments (mainly aspirin). In addition, the recent revisions of diagnostic criteria27,28 render comparisons across different patient cohorts quite problematic.

The incidence of major thrombosis in PV and ET derives mainly from observational and retrospective studies2-4,29-37 (Tables 1 and 2). In reviewing these studies, we only considered those that allowed estimating the annualized incidence of thrombotic and/or hemorrhagic events. Thromboses involve arteries in approximately two-thirds of cases in both disorders. The incidence of major and minor arterial and venous thromboses ranged from 1.1% to 4.9% per year in PV, and from 1.3% to 6.6% per year in ET (Table 1). Such figures vary mainly according to age and previous thrombosis, which are the 2 main factors consistently identified as predictors of thrombosis and currently used for risk stratification (Table 2).

The largest prospective data for PV and ET derive from the European Collaboration on Low-Dose Aspirin in Polycythemia Vera (ECLAP) study4 and from the Primary Thrombocythemia-1 (PT-1) trial,32 respectively. The ECLAP cohort included 1638 PV patients monitored independently of their inclusion in the randomized trial. In this cohort, the incidence of thrombosis was 4.9% per year, ranging from 2.5% to 10.9% according to age and previous thrombosis4 (Table 2). In the PT-1 trial, 809 high-risk ET patients were randomized to hydroxyurea (n = 404, 69% with previous thrombosis) or anagrelide (n = 405, 71% with previous thrombosis) on a background of aspirin.32 The overall incidence of thrombosis was 2.6% per year, with more venous thromboses in the hydroxyurea arm and more TIA in the anagrelide arm. Based on indirect comparison of different studies, the rate of first major and minor thrombosis in PV seems higher than in ET, independently of age (Table 2).2-4,29-41 Nevertheless, the incidence appears similar when only major nonfatal arterial (MI, ischemic stroke) and venous thromboembolism (DVT, PE) are considered: major arterial thrombosis ranged between 0.4% and 1.7% per year in PV and 0.6% and 1.3% in ET (Table 1); major venous thromboembolism ranged between 0.3% and 1.5% per year in PV and 0.2% and 1.5% in ET (Table 1). Moreover, the rate of cardiovascular death has been reported between 0.43% and 0.72% per year in PV2-4 and 0.47% per year in ET.3

In the general population of the Western countries, the annual incidence of major venous thromboembolism is between 0.1% and 0.2%.42 In patients with PV43 or ET30 not treated with aspirin, the incidence of DVT and/or PE seems ∼10-fold higher, being 1.5% and 1.0% per year, respectively (Table 1). In the prospective randomized ECLAP trial43 and in the PT-1 trial,32 the PV and ET patients receiving aspirin had an incidence of major venous thromboembolism of 0.5% and 0.6% per year, respectively.

In a meta-analysis of 6 primary prevention aspirin trials in ∼95 000 participants, the control annual rate of any major coronary event and ischemic stroke was 0.34% and 0.36%, respectively.44 Similar control rates (ie, 0.3% and 0.4% per year, respectively) have been reported in a meta-analysis of randomized trials of cyclooxygenase (COX)–2 inhibitors and traditional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs involving ∼145 000 participants.45 In the control arm of the ECLAP trial in PV patients, the annual rate of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke was 0.2% and 1.1%, respectively.43

Incidence of recurrent arterial and venous thromboembolism.

The risk of recurrence after a first thrombosis is difficult to estimate because the published cohorts included patients with and without a previous event.2-4,30-37 There is only one retrospective study investigating the incidence of recurrent thrombosis in 235 PV and 259 ET patients after a first thrombotic event.29 Microvascular events, except for TIA, were not included as a primary outcome. Overall, thrombosis recurred in 166 patients (33.6%), corresponding to 5.6% per year; recurrence was 6.0% and 5.3% per year in PV and ET, respectively, with a 1.7-fold increased risk in patients aged >60 years.29

Efficacy and safety of aspirin

Aspirin prevents fatal and nonfatal major vascular events by ∼25% in non-MPN patients at high cardiovascular risk because of a previous vascular event.44 Recently, the efficacy of low-dose aspirin in the secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism after vitamin K antagonists has been reported in non-MPN patients.46 Low-dose aspirin increases the risk of major extracranial (largely gastrointestinal) bleeds by ∼1.5- to 2.0-fold in randomized trials and observational studies.44,47 Because the clinical development of aspirin as an antithrombotic agent was not industry driven, a wide range of doses and dosing regimens were tested by independent studies, from as low as 30 mg to as high as 1500 mg daily.47 Lower doses (75-150 mg) were as effective as higher doses and associated with reduced gastrointestinal toxicity.47

Primary prophylaxis.

In the ECLAP trial, 518 PV patients, 90% without previous thrombosis, were randomized to 100 mg aspirin daily or a placebo.43 Aspirin nonsignificantly reduced the risk of a combined primary end point including nonfatal MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death (relative risk, 0.41; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.15-1.15; P = .08), but the inclusion of major venous thromboembolism in a combined coprimary end point led to a statistically significant risk reduction (relative risk, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.18-0.91; P = .02).43 This apparent protection appears larger than in non-MPN patients44 ; however, the ECLAP trial was terminated prematurely because of the slow recruitment rate, enrolling approximately one-third of the planned population. Thus, the apparent benefit of antiplatelet therapy remains of substantial statistical uncertainty in this setting. In the whole prospective ECLAP cohort (including both randomized and observational studies), 38% of patients had a prior thrombosis, and antiplatelet therapy reduced the incidence of cardiovascular events by 28%4 (ie, an effect size comparable to non-MPN patients).44 Based on these results, primary prophylaxis with low-dose (81-100 mg) aspirin is currently recommended in PV.5,6,48

No randomized trials have directly assessed the efficacy and safety of low-dose aspirin in ET. Microvascular disturbances typical of ET, such as erythromelalgia, TIA, and migraine-like symptoms, have been reported to be extremely sensitive to aspirin in small-sized studies.49,50 An early trial randomized 114 ET patients to hydroxyurea (n = 56, 54% with previous thrombosis) or observation (no myelosuppression, n = 58, 38% with previous thrombosis), and 70% of the patients in each arm received antiplatelet agents (300 mg aspirin or 500 mg ticlopidine daily).51 In the hydroxyurea group, 2 patients (3.6%) experienced MI and ischemic stroke, whereas in the control group, 14 (24%) had major or minor thromboses, but only 2 patients (3.4%) had major thromboses (ie, ischemic stroke and DVT).51

A recent retrospective study in low-risk ET patients (<60 years, without thrombosis and cytoreduction), 198 on antiplatelet drugs only (mainly 100 mg aspirin daily) and 102 under careful observation, showed a similar incidence of thrombosis with or without aspirin (2.1% vs 1.7% per year, respectively; P = .6).40

Secondary prophylaxis.

The effects of cytoreduction and antithrombotic prophylaxis have been investigated in the aforementioned cohort including only PV and ET patients with previous thrombosis.29 By multivariate analysis, cytoreduction was associated with a statistically sign1ificant risk reduction in the entire cohort (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.38-0.73), which was confirmed in the patients with a first arterial thrombosis (HR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.31-0.70); in patients with a first venous event, the risk reduction associated with cytoreduction was not statistically significant (HR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.38-1.13). In patients with a first arterial thrombosis, antiplatelet agents were associated with a nonsignificant risk reduction (HR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.41-1.08), whereas in patients with a first venous event, both antiplatelet drugs and vitamin K antagonists were associated with significantly lower risk of recurrence (HR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.22-0.77; and HR = 0.32; 95% CI, 0.15-0.64, respectively).29

Safety.

Aspirin was initially discouraged in PV after the Polycythemia Vera Study Group 05 trial,52 which randomized 166 patients to phlebotomy plus 300 mg aspirin thrice daily and 75 mg dipyridamole thrice daily or 32P. No hemorrhagic complications occurred in the 32P arm, whereas 7.2% of patients in the antiplatelet arm experienced bleeding, most likely reflecting the high aspirin dose.

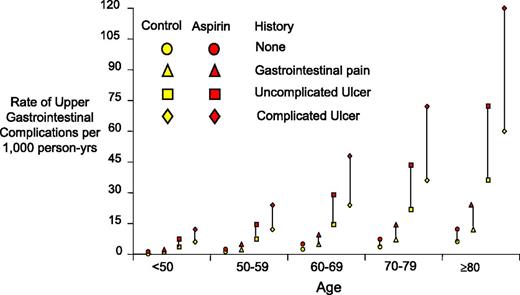

In patients with MPN, the overall incidence of major hemorrhages (both intracranial and gastrointestinal) ranges between 0.3% and 0.8% per year (Table 1). The rate of intracranial bleeding has been reported between 0.03% and 0.2% per year; however, in prospective studies the rate of intracranial bleeding among the PV43 or ET32 aspirin-treated patients has been consistently reported as 0.2% per year (Table 1), which seems higher than that observed in the aspirin-allocated participants in primary and secondary prevention trials (0.04%).44 The incidence of major gastrointestinal bleeding has been reported between 0% and 0.3% per year in the absence of aspirin treatment,30,43 but in the cohorts where aspirin has been administrated to >70% of patients, the incidence of major gastrointestinal bleeding was between 0.3% and 1.2% per year (Table 1). In primary prevention trials, the annual rate of major gastrointestinal bleeding was 0.07% and 0.1% per year in control and aspirin-treated participants, respectively.44 However, any indirect comparison of the data obtained in MPN patients and non-MPN individuals is weakened by the relatively small number of MPN patients investigated and by the high variability of the baseline risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding depending on age and prior gastrointestinal history (Figure 2).47

Estimated rates of upper gastrointestinal complications in men, according to age and the presence or absence of a history of such complications and regular treatment with low-dose aspirin. The solid lines connecting each pair of yellow and red symbols depict the absolute excess of complications related to aspirin therapy. Adapted from Patrono et al47 with permission.

Estimated rates of upper gastrointestinal complications in men, according to age and the presence or absence of a history of such complications and regular treatment with low-dose aspirin. The solid lines connecting each pair of yellow and red symbols depict the absolute excess of complications related to aspirin therapy. Adapted from Patrono et al47 with permission.

In retrospective PV cohorts, fatal bleeding accounted for 3.1% of all deaths,2 with 0.07% per year incidence.3 In the ECLAP cohort, the incidence of fatal bleeding was 0.15% per year, independently of antiplatelet treatment.4 In patients with ET, the annual rate of fatal bleeding was 0.02% in a retrospective study (57% of patients on aspirin)3 and 0.3% in a prospective study (all patients on aspirin).32

Extreme thrombocytosis has been associated with increased bleeding, although the platelet threshold remains controversial (between 750 and 1500 × 109/L) and the relationship is likely nonlinear.53 This phenomenon has been attributed to acquired von Willebrand syndrome.54,55 However, in 99 ET patients aged <60 years and with extreme thrombocytosis at diagnosis, the incidence of major thrombosis was 0.15% and 0.13% per year with and without cytoreduction, respectively, with a major bleeding rate of 0.05% and 0.04% per year, thus challenging the association of thrombocytosis with bleeding.56 Aspirin use was comparable in the 2 groups (44% and 54%, respectively), but information concerning bleeding among the aspirin-treated patients is lacking.56 Moreover, in a large retrospective cohort of 891 ET patients,36 the annual rate of major bleeding was 0.79%, and, on multivariate analysis, thrombocytosis >1000 × 109/L did not enhance bleeding risk, whereas aspirin increased the risk by 3.1-fold independently of the platelet count. In aspirin-naive patients, the incidence of major bleeding was 0.46% and 0.49% per year in patients below and above 1000 × 109 platelets per L, respectively; in aspirin-treated patients, the incidence was 0.95% and 1.08% per year below and above the same threshold, respectively.36 In contrast, in a cohort of low-risk ET patients the incidence of major bleeding in those receiving aspirin or not was 1.26% and 0.6% per year, respectively (P = .09), and only thrombocytosis >800 × 109/L was independently associated with increased bleeding.40 In another retrospective study including aspirin-treated ET patients, bleeding risk was doubled in association with thrombocytosis >1000 × 109/L but was not affected by aspirin.37 Finally, in the ET patients recruited in the PT-1 high-risk trial, platelet count at diagnosis could not predict future bleedings.53 The analysis of 21 887 longitudinal blood counts collected from 776 aspirin-treated ET patients enrolled to 1 of the 3 PT-1 studies confirmed the lack of predictivity of platelet count at diagnosis. However, during follow-up the risk of major bleeding approximately doubled for platelet counts between 750 and 1000 × 109/L and increased exponentially beyond 1000 × 109/L.53

How to assess the adequacy of platelet COX-1 inhibition and aspirin “resistance”

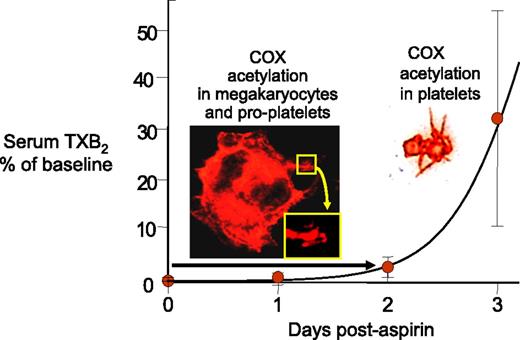

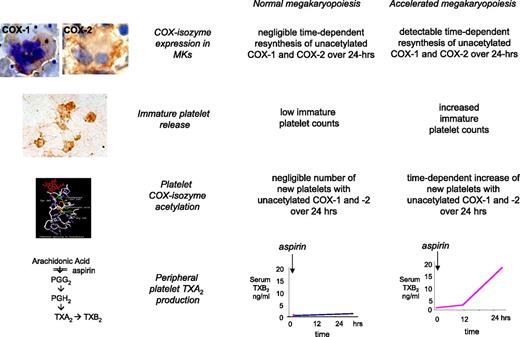

The mechanism of action of low-dose aspirin in preventing atherothrombosis relies on the irreversible acetylation of a single serine residue near the active site of platelet prostaglandin (PG) H–synthase 1, hampering the access of arachidonic acid (AA) to the catalytic site of COX activity and inhibiting the subsequent biosynthesis of TXA2.47 In spite of aspirin’s short half-life (20 minutes in the human circulation), blockade of platelet COX-1 activity lasts for the entire life span due to the limited platelet capacity for new protein synthesis, thus allowing once-daily dosing. Moreover, aspirin acetylates a variable fraction of COX isozymes in the bone marrow megakaryocytes57 and proplatelets, as suggested by a 24- to 48-hour delay between aspirin withdrawal and reappearance of TXA2 biosynthesis in peripheral platelets (Figure 3).58-60 Thus, under normal conditions, a 24-hour dosing interval of a short-lived drug is ensured by a favorable combination of the irreversible inhibition of a slowly renewable drug target (platelet COX-1) and an effect on progenitors, leading to a new platelet progeny with a largely nonfunctioning enzyme throughout the dosing interval (Figure 4).25

Recovery of serum TXB2 after aspirin withdrawal in healthy subjects. Following aspirin withdrawal in 48 aspirin-treated healthy subjects, the recovery of platelet COX-1 activity shows a 24- to 48-hour delay before linear increase of serum TXB2. This delay is likely due to the degree of acetylation of bone marrow megakaryocytes and proplatelets. Adapted from Santilli et al60 with permission.

Recovery of serum TXB2 after aspirin withdrawal in healthy subjects. Following aspirin withdrawal in 48 aspirin-treated healthy subjects, the recovery of platelet COX-1 activity shows a 24- to 48-hour delay before linear increase of serum TXB2. This delay is likely due to the degree of acetylation of bone marrow megakaryocytes and proplatelets. Adapted from Santilli et al60 with permission.

Model of altered aspirin pharmacodynamics in ET. Under conditions of normal megakaryopoiesis, low-dose aspirin acetylates COX isozymes in both circulating platelets and bone marrow megakaryocytes, and only negligible amounts of unacetylated enzymes are resynthesized within the 24-hour dosing interval. This pharmacodynamic pattern is associated with virtually complete suppression of platelet TXA2 production in peripheral blood throughout the dosing interval. Under conditions of abnormal megakaryopoiesis, an accelerated rate of COX-isozyme resynthesis is biologically plausible in bone marrow megakaryocytes, accompanied by faster release of immature platelets with unacetylated enzyme(s) during the aspirin dosing interval, and in particular between 12 and 24 hours after dosing. This pharmacodynamic pattern is associated with incomplete suppression of platelet TXA2 production in peripheral blood and time-dependent recovery of TXA2-dependent platelet function during the 24-hour dosing interval. Immunohistochemistry panels depict megakaryocytes from an ET patient stained for COX-1 and from a normal subject stained for COX-2, and peripheral washed platelets from an ET patient stained for COX-2. Reprinted from Pascale et al25 with permission.

Model of altered aspirin pharmacodynamics in ET. Under conditions of normal megakaryopoiesis, low-dose aspirin acetylates COX isozymes in both circulating platelets and bone marrow megakaryocytes, and only negligible amounts of unacetylated enzymes are resynthesized within the 24-hour dosing interval. This pharmacodynamic pattern is associated with virtually complete suppression of platelet TXA2 production in peripheral blood throughout the dosing interval. Under conditions of abnormal megakaryopoiesis, an accelerated rate of COX-isozyme resynthesis is biologically plausible in bone marrow megakaryocytes, accompanied by faster release of immature platelets with unacetylated enzyme(s) during the aspirin dosing interval, and in particular between 12 and 24 hours after dosing. This pharmacodynamic pattern is associated with incomplete suppression of platelet TXA2 production in peripheral blood and time-dependent recovery of TXA2-dependent platelet function during the 24-hour dosing interval. Immunohistochemistry panels depict megakaryocytes from an ET patient stained for COX-1 and from a normal subject stained for COX-2, and peripheral washed platelets from an ET patient stained for COX-2. Reprinted from Pascale et al25 with permission.

The platelet pharmacology of aspirin has been described best by the ex vivo synthesis of TXA2 during whole blood clotting, measured as its stable hydrolysis product, TXB2, in serum (Figure 5).61 This relatively simple assay of aspirin pharmacodynamics characterized the cumulative nature of platelet COX-1 inactivation upon repeated daily dosing and demonstrated saturability of the antiplatelet effect at low doses,62 in the same dose range later shown to be clinically effective.63 High residual serum TXB2 has been identified as a predictor of poor outcome in aspirin-treated patients presenting for cardiac catheterization.64

Principle and kinetics of the serum TXB2 ex vivo assay. (A) The chain of enzymatic reactions triggered by whole blood clotting in vitro at 37°C. Thrombin generated during blood clotting activates platelet phospholipases A2 (PLA2), which releases AA from membrane phospholipids. AA is the substrate of the sequential action of COX-1 and TX synthase, resulting in TXA2 generation. Because of chemical instability of its oxane ring, TXA2 is rapidly hydrolyzed to the chemically stable, biologically inactive hydration product, TXB2, which can be measured in serum with high sensitivity and specificity. (B) The kinetics of TXB2 production during whole blood clotting at 37°C and based on data from Patrono et al.61

Principle and kinetics of the serum TXB2 ex vivo assay. (A) The chain of enzymatic reactions triggered by whole blood clotting in vitro at 37°C. Thrombin generated during blood clotting activates platelet phospholipases A2 (PLA2), which releases AA from membrane phospholipids. AA is the substrate of the sequential action of COX-1 and TX synthase, resulting in TXA2 generation. Because of chemical instability of its oxane ring, TXA2 is rapidly hydrolyzed to the chemically stable, biologically inactive hydration product, TXB2, which can be measured in serum with high sensitivity and specificity. (B) The kinetics of TXB2 production during whole blood clotting at 37°C and based on data from Patrono et al.61

The relationship between inhibition of serum TXB2 and AA-dependent platelet function assays (ie, AA-induced optical aggregation), Verify-Now Aspirin, and urinary TXA2 metabolites (11-dehydro-TXB2) is strikingly nonlinear (Figure 6).60,65 Thus, platelet COX-1 activity must be nearly completely (∼99%) suppressed to fully inhibit in vivo platelet activation.60,65 Given this relationship, platelet function assays, including urinary 11-dehydro-TXB2, are poorly sensitive to and do not linearly reflect the degree of COX-1 inactivation.25,66 Moreover, many platelet function assays often used to measure aspirin response, are unrelated to its mechanism of action, display poor agreement,60,67,68 and give variable results upon repeated measurements.60,69 This methodological background helps explain the aspirin “resistance” phenomenon, usually defined as lower-than-expected response to aspirin in heterogeneous studies, without an objective assessment of compliance.70 Not surprisingly, the incidence of resistance ranges from 1% up to 65%, is assay-dependent, fluctuates over time, and has uncertain clinical significance.70 The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis defined this phenomenon as “variability in laboratory test response,” rather than “resistance” to aspirin and recommended against monitoring aspirin response by standard aggregation.71 Aspirin “resistance” has been considered in ET.72

Correlations between biochemical and functional assays of platelet response to aspirin in healthy subjects and patients with ET. Individual percent inhibition values are depicted from healthy volunteers (n = 48) during aspirin treatment (100 mg daily) and following its withdrawal. The nonlinear relationships between percent inhibition of serum TXB2 and Verify-Now Aspirin (A), AA-induced platelet aggregation (B), and urinary 11-dehydro-TXB2 (C). (D) The relationship between absolute values of serum TXB2 and Verify-Now Aspirin measurements performed in 15 ET patients during different aspirin regimens. The dotted line represents the best fitting of the experimental data (logarithmic relation between the 2 variables: y = 40ln[x] + 378, R2 = 0.43; n = 75). Each point in the graph represents the median value for each aspirin regimen, and the horizontal and vertical bars indicate the correspondent interquartile range (25th to 75th percentile). bid, twice daily; EC, enteric coated aspirin; od, once daily. Reprinted from Santilli et al60 and Pascale et al25 with permission.

Correlations between biochemical and functional assays of platelet response to aspirin in healthy subjects and patients with ET. Individual percent inhibition values are depicted from healthy volunteers (n = 48) during aspirin treatment (100 mg daily) and following its withdrawal. The nonlinear relationships between percent inhibition of serum TXB2 and Verify-Now Aspirin (A), AA-induced platelet aggregation (B), and urinary 11-dehydro-TXB2 (C). (D) The relationship between absolute values of serum TXB2 and Verify-Now Aspirin measurements performed in 15 ET patients during different aspirin regimens. The dotted line represents the best fitting of the experimental data (logarithmic relation between the 2 variables: y = 40ln[x] + 378, R2 = 0.43; n = 75). Each point in the graph represents the median value for each aspirin regimen, and the horizontal and vertical bars indicate the correspondent interquartile range (25th to 75th percentile). bid, twice daily; EC, enteric coated aspirin; od, once daily. Reprinted from Santilli et al60 and Pascale et al25 with permission.

Measurements of serum TXB2 were instrumental in characterizing the inhibition of platelet COX-1 activity by low-dose aspirin in PV,73 providing the rationale for testing its efficacy and safety in this setting.43 Similarly to PV, patients with ET display enhanced TXA2 biosyntheses in vivo.7 However, the same once-daily regimen of 100 mg aspirin shown effective in PV was unable to fully inhibit platelet TXA2 production in ∼80% of ET patients.74 The residual platelet COX (both COX-1 and COX-2) activity was fully suppressed by adding aspirin to whole blood in vitro,74 thus demonstrating that platelet COX isozymes are not “resistant” to aspirin.74 Additional studies demonstrated that aspirin-insensitive TXA2 biosynthesis in ET is explained by accelerated renewal of the drug target.25 The abnormal megakaryopoiesis that characterizes ET accounts for shorter-lasting antiplatelet effects of low-dose aspirin through faster renewal of platelet COX-1, as modeled in Figure 4.25

Is there a need for “tailored” antiplatelet therapy in MPN?

Current risk stratification in PV and ET is designed to estimate the likelihood of thrombotic complications: high-risk is defined by age ≥60 years or thrombosis history; low-risk is defined by age <60 years and no thrombosis history.5,6,48 Cardiovascular risk factors are not taken under consideration in formal risk categorization in the current clinical practice. Very recently, a prognostic score for thrombosis including some of the traditional cardiovascular risk factors (smoking habits defined as “active tobacco use,” hypertension, diabetes) and the presence of JAK2 V617F, besides age and thrombosis history, has been developed,75 but further prospective studies are needed to validate such a score. Similarly, the risk of bleeding complications is evaluated only with respect to acquired von Willebrand syndrome, especially in the presence of extreme thrombocytosis (platelets >1000 × 109/L).6 In the 2012 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management of PV and ET, low-dose aspirin (81 mg/d; range 40-100 mg/d) is recommended in all patients, irrespective of risk category, with the notable exception of patients with PV or ET and extreme thrombocytosis, if ristocetin cofactor activity is <30%.6 Risk-adapted therapy considers cytoreductive therapy (eg, hydroxyurea, interferon-α) according to individual disease and risk category.

As noted above, the randomized evidence for the efficacy and safety of low-dose aspirin in MPN is limited to 1 clinical trial in PV43 with inadequate statistical power to detect differences in major bleeding complications because of its relatively small sample size. Thus, whether the potential benefits of reduced thrombotic risk demonstrated in PV also apply to ET, and whether the balance of benefits and risk of bleeding complications of antiplatelet therapy is favorable in all clinical scenarios, is currently unknown. Extrapolation from randomized trials of low-dose aspirin in people without MPN44 may provide useful information, particularly for patients without thrombosis history, inasmuch as most traditional cardiovascular risk factors appear to influence both the risk of atherothrombotic and hemorrhagic complications.44 In the Antithrombotic Trialists’ meta-analysis of 6 primary prevention trials, low-dose aspirin reduced the risk of major vascular events by approximately one-tenth largely due to a reduction in nonfatal MI.44 On the other hand, low-dose aspirin roughly doubled the risk of major extracranial hemorrhages. When considering age (as a continuous variable) and prior gastrointestinal history as risk factors, the absolute excess of upper gastrointestinal complications due to aspirin can vary ∼100-fold when comparing the lowest to the highest risk category (Figure 2).47 Therefore, we suggest that when considering low-dose aspirin for primary prevention, the bleeding risk profile of the individual patient should be carefully examined along the lines depicted in Figure 2.

Finally, the recommendation of the same aspirin dose range (40-100 mg) and dosing regimen (once daily) for ET patients as for non-MPN patients implies assuming similar antiplatelet pharmacodynamics. We have shown that the duration of the antiplatelet effect of low-dose aspirin is in fact shortened in the majority of aspirin-treated ET patients, most likely reflecting accelerated renewal of the drug target.25 Inadequate suppression of platelet TXA2 production during the 24-hour dosing interval is largely overcome by a twice-daily regimen of low-dose aspirin.25 Thus, we suggest testing for the adequacy of platelet COX-1 inactivation by 2 repeated measurements of serum TXB2, a validated surrogate marker of efficacy,76 performed 24 hours after a witnessed administration of low-dose aspirin in ET patients treated for at least 2 weeks with a conventional regimen. A serum TXB2 concentration consistently above 4.0 ng/mL, the upper limit of values observed in aspirin-treated healthy subjects,60 should warrant considering a twice-daily regimen of aspirin administration, although the clinical effectiveness of such a strategy remains to be tested.

Is the chemopreventive effect of aspirin of any relevance to the balance of benefits and risks in MPN?

Long-term follow-up of patients randomized in trials of daily aspirin vs control for cardiovascular prevention has shown that low-dose aspirin reduces the incidence and mortality due to colorectal cancer after a delay of 8-10 years77,78 and reduces deaths due to several other common cancers after 5-15 years’ delay.79 The lowest doses used in these trials (75-100 mg once daily) appeared as effective as higher doses (300-1200 mg daily). Subsequently, a pooled analysis of 6 primary prevention trials of daily low-dose aspirin use (75-100 mg) found a similar reduction (HR = 0.76; 95% CI, 0.66-0.88; P = .0003) in overall cancer incidence occurring after ≥3 years on aspirin and a reduction in total cancer mortality (HR = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.47-0.86; P = .004) from 5 years onward.80

Some caveats in interpreting these findings should be mentioned. First, cancer incidence and mortality were not prespecified end points of these cardiovascular trials. Second, the analyses by Rothwell et al78-80 excluded the Physicians’ Health Study81 and the Women’s Health Study82 because in these trials aspirin was given every other day. Although mechanistic considerations may justify a separate analysis based on the 24-hour vs 48-hour dosing interval, this was a post hoc separation that may be subject to bias.

The mechanism of the chemopreventive effects of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs against colorectal adenoma and cancer has long been related to shared inhibition of COX-2 activity in various cell types of the lower gastrointestinal tract.83 The main product of COX-2 in epithelial and stromal cells, PGE2, can modulate apoptosis and cell proliferation.83 Moreover, COX-2 deletion in mice and COX-2 inhibitors in humans were demonstrated to protect against the development or recurrence of both familial and sporadic colorectal adenomas.83,84 However, several findings suggest the need to reconsider both the cellular and molecular targets of aspirin action. These include (1) the demonstration that COX-1 gene deletion is just as protective as COX-2 knockout in a murine model of intestinal polyposis85 ; (2) the results of 4 placebo-controlled randomized trials86-89 of once-daily aspirin, at doses as low as 81 mg, which showed a largely similar chemopreventive effect against the recurrence of a sporadic colorectal adenoma as demonstrated with selective COX-2 inhibitors90,91 ; and (3) the recent finding of Rothwell et al78,79 of a chemopreventive effect of once-daily aspirin regimens, at doses as low as 75-100 mg, against overall cancer incidence and mortality. Thus, the apparent chemopreventive effect of aspirin in humans appears to recapitulate the unique features of its antithrombotic effect, that is, the adequacy of a 24-hour dosing interval (despite a 15- to 20-minute half-life of the drug in the human circulation) and saturability of the protective effect at low doses.84 This, in turn, could reflect a common mechanism of action of the drug in protecting against atherothrombosis and cancer (ie, permanent inactivation of platelet COX-1).92 This working hypothesis could be reconciled with the established role of COX-2 in colorectal carcinogenesis by postulating that activated platelets may induce COX-2 expression in adjacent nucleated cells (eg, stromal cells) at sites of intestinal mucosal injury.84 This hypothetical sequence would involve platelet signaling through paracrine mediators of both lipid (eg, prostanoids) and protein (eg, growth factors, inflammatory cytokines) nature, in turn inducing COX-2 expression and an eicosanoid amplification loop promoting cell proliferation and angiogenesis.84,92

Using population-based data from the Danish health care system, Frederiksen et al93 have recently reported that MPN patients are at increased risk of developing both new hematologic and nonhematologic cancers. The standardized incidence ratio for developing a nonhematologic cancer was 1.2 (95% CI, 1.0-1.4) for patients with ET and 1.4 (95% CI, 1.3-1.5) for patients with PV. Interestingly, this study showed no increased incidence of colorectal cancer among (mostly aspirin treated) MPN patients in contrast to other solid tumors.93 Clearly, additional studies are required to test the hypothesis that long-term exposure to low-dose aspirin may exert chemopreventive effects in the setting of MPN.

The need for and feasibility of new antiplatelet trials in MPN

As detailed in the previous sections, studies in ET patients with or without previous thrombosis did not show a clear-cut benefit or harm of low-dose aspirin,29,40 possibly reflecting the observational nature and relatively small sample size of the studies. Furthermore, measurement of a surrogate biomarker of aspirin efficacy, serum TXB2,61,76 showed that platelets from ∼80% of aspirin-treated ET patients were inadequately inhibited by the traditional once-daily low-dose regimen.25,74 Extrapolation to ET patients of the 100-mg once-daily regimen tested in the ECLAP trial43 does not seem to be justified in light of altered aspirin pharmacodynamics in ET.25,74 A twice-daily regimen of 100 mg aspirin successfully improved the inhibition of serum TXB2 in a small, proof-of-concept study.25 Although twice-daily dosing may reduce compliance and inhibit prostacyclin (PGI2) biosynthesis as compared with a once-daily regimen, such an approach has been used successfully for stroke prevention in patients with cerebrovascular disease.94

Based on the high cardiovascular risk associated with previous vascular events in ET, despite standard antiplatelet therapy, a phase 3 study testing the efficacy and safety of an improved dosing schedule vs the traditional aspirin regimen in secondary prophylaxis seems warranted. The most appropriate aspirin dose and dosing interval to be tested against the traditional dosing regimen should be identified through a properly sized, dose-finding study. This should measure mechanism-based, surrogate biomarkers of efficacy and safety, that is, serum TXB261,76 and urinary 2,3-dinor-6-keto-PGF1α,95 respectively, to test the adequacy of platelet COX-1 inactivation and sparing of endothelial COX-2, throughout a variable dosing interval of aspirin in the low-dose range. The most effective experimental regimen should then be tested vs the standard aspirin regimen on clinical outcomes (eg, the combination of major arterial and venous events). Major issues in designing a phase 3 study would be feasibility and estimating the expected event rate and hypothesized effect size. Concerning feasibility, the previous experience of the ECLAP trial43 has identified key issues in recruiting patients across several European countries with relatively limited funding. A transatlantic network of collaborating centers may help address these issues through a pilot feasibility study of 12-month duration, incorporating biochemical assessment of compliance as a key secondary objective.

A conservative estimate of the annual incidence of major vascular events would be ∼5% in ET patients with previous thrombosis. The benefit of the experimental aspirin regimen would be reasonably anticipated to be a 25% to 30% relative risk reduction in major vascular events.63 Depending on sample size and duration of follow-up, this randomized trial could also evaluate overall cancer incidence and mortality as key secondary end points. Such a study might provide a unique opportunity to assess whether optimizing antithrombotic treatment can reduce bone marrow fibrosis.96 Given the size of the unmet therapeutic need in high-risk ET patients, a 2 × 2 factorial design could also test the hypothesis that dual antiplatelet therapy with a novel P2Y12 blocker (prasugrel or ticagrelor)97 may further reduce the atherothrombotic burden in this setting.

Conclusions

Persistently enhanced platelet activation has been convincingly demonstrated in PV and ET, and this abnormality contributes to a higher risk of both arterial and venous thrombotic complications. The incidence of major bleeding complications (both intra- and extracranial) is somewhat higher in PV and ET patients than in the general population. However, it should be emphasized that other risk factors, such as age and prior ulcer history, may dramatically enhance the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding complications (Figure 2) to an extent that is likely to dwarf the enhanced risk due to the MPN state. In the absence of statistically robust estimates of the aspirin effect size in protecting against thrombosis and amplifying bleeding risk, it seems reasonable to suggest that the more reliable estimates of these effects in the non-MPN population44 should be applied to PV and ET patients when assessing the balance of benefits and risks of antiplatelet therapy.

Although for most PV and ET patients with a thrombosis history the benefit/risk profile of antiplatelet therapy with aspirin is likely to be favorable, in patients with no such history this balance will depend importantly on the level of thrombotic and hemorrhagic risks of the individual patient.

Recent evidence for a chemopreventive effect of low-dose aspirin may tilt the balance of benefits and harm in favor of using aspirin more broadly, but the potential for additional benefits needs regulatory scrutiny and novel treatment guidelines.

A clear pharmacodynamic rationale and analytical tools are available for a personalized approach to antiplatelet therapy in ET, and an improved regimen of low-dose aspirin therapy should be tested in a properly sized randomized trial.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Daniela Basilico and Ms Patrizia Barbi for expert editorial assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the European Commission (FP6 EICOSANOX Consortium, Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement no. 115006, the SUMMIT consortium, the resources of which are composed of financial contribution from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme, FP7/2007-2013, and EFPIA companies’ in-kind contribution).

Authorship

Contribution: C.P., B.R., and V.D.S. designed and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.P. received consultant and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Merck, NicOx, and Novartis and received grant support for investigator-initiated research from the European Commission, FP6 and FP7 Programmes, and Bayer. B.R. received speaker fees from Shire and Astra Zeneca. V.D.S. received honoraria as a consultant from Amgen-Dompè, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, and Shire and received research grants from Janssen-Cilag and Shire.

Correspondence: Carlo Patrono, Department of Pharmacology, Catholic University School of Medicine, Largo F. Vito 1, 00168 Rome, Italy; e-mail: carlo.patrono@rm.unicatt.it.

![Figure 6. Correlations between biochemical and functional assays of platelet response to aspirin in healthy subjects and patients with ET. Individual percent inhibition values are depicted from healthy volunteers (n = 48) during aspirin treatment (100 mg daily) and following its withdrawal. The nonlinear relationships between percent inhibition of serum TXB2 and Verify-Now Aspirin (A), AA-induced platelet aggregation (B), and urinary 11-dehydro-TXB2 (C). (D) The relationship between absolute values of serum TXB2 and Verify-Now Aspirin measurements performed in 15 ET patients during different aspirin regimens. The dotted line represents the best fitting of the experimental data (logarithmic relation between the 2 variables: y = 40ln[x] + 378, R2 = 0.43; n = 75). Each point in the graph represents the median value for each aspirin regimen, and the horizontal and vertical bars indicate the correspondent interquartile range (25th to 75th percentile). bid, twice daily; EC, enteric coated aspirin; od, once daily. Reprinted from Santilli et al60 and Pascale et al25 with permission.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/121/10/10.1182_blood-2012-10-429134/4/m_1701f6.jpeg?Expires=1769415083&Signature=AcY1y9YqrIy2jCjuQXm5Zjqv1cxHMBLZUN39zn3FOJp-J4rjTpDVkt5z~~dL5eR-KezBgHSPcqBk8PdtJIavld1BFaAnZj--5Wu7THbCq~UxqQ1NOyArVHfugEDbOuUfuOsVEeoHRTO7QMGyr6vWt9tItpinKUHf8XAP36OjX~PVjTTQ9ig8ysZA~tBMvkehHEdV9ybAvJ8bqsik7gE3DRlxQrwK759pydaiwMHPeWYOO-pIqDFAR~raNnOsTaWaA3hBrchFEeXtX7OxYe5Vpg7p2b~scgO4lMc3aeW9QiR7msfjIFWIo~MRAQ15R9NAiQEJ97UvQpwk2gLtaLuXVw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)