Abstract

The Graffi murine leukemia virus induces a large spectrum of leukemias in mice and thus provides a good model to compare the transcriptome of all types of leukemias. We analyzed the gene expression profiles of both T and B leukemias induced by the virus with DNA microarrays. Given that we considered that a 4-fold change in expression level was significant, 388 probe sets were associated to B, to T, or common to both leukemias. Several of them were not yet associated with lymphoid leukemia. We confirmed specific deregulation of Fmn2, Arntl2, Bfsp2, Gfra2, Gpm6a, and Gpm6b in B leukemia, of Nln, Fbln1, and Bmp7 in T leukemias, and of Etv5 in both leukemias. More importantly, we show that the mouse Fmn2 induced an anchorage-independent growth, a drastic modification in cell shape with a concomitant disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. Interestingly, we found that human FMN2 is overexpressed in approximately 95% of pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the highest expression levels in patients with a TEL/AML1 rearrangement. These results, surely related to the role of FMN2 in meiotic spindle maintenance, suggest its important role in leukemogenesis. Finally, we propose a new panel of genes potentially involved in T and/or B leukemias.

Introduction

To understand the mechanism of induction of leukemia in humans, the mouse has been considered to be an ideal model given the extent of genetic similarity between these 2 species. We have already shown that the Graffi murine leukemia virus (MuLV), when inoculated into newborn mice, induces a broad spectrum of leukemias of lymphoid (T or B) and nonlymphoid (myeloid, erythroid, or megakaryoblastic) origins.1 We also demonstrated that the Graffi MuLV directly targets the c-Myc, Fli1, Pim1, and Spi1/P1 oncogenes2 but also the Gris1 locus that encodes an oncogenic truncated form of cyclin D2.3,4 We took advantage of the large spectrum of leukemias induced by the Graffi murine leukemia virus to analyze and compare the transcriptome of these leukemias with a DNA microarray approach. One clear advantage of microarray analysis is that genes that are not targeted through retroviral integration but act as oncogene on deregulation can be equally identified. Using this approach, we recently identified several genes that are directly involved in erythroid and megakaryoblastic leukemias in both mouse and human.5 In this report, we have specifically compared the transcriptomes of T and B lymphoid leukemias induced by Graffi MuLV with their corresponding controls. We identified new relevant signatures that highlight many potential markers or oncogenes for T and B leukemias (especially for pre-B-leukemia), some of which were common to both types of lymphoid leukemia. Among the selected genes, we validated the modulation of the expression of 10 genes of 12, the functions of which remained poorly elucidated in lymphoid leukemias. Furthermore, for the first time, we provide data supporting a role for Fmn2, a member of the formin family in leukemogenesis in pre-B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) and particularly, in pediatric pre-B-ALL harboring the t(12;21) TEL/AML1 translocation.

Methods

Human sample collection

For this study, samples from 12 pediatric pre-B-ALL were obtained from Dr Daniel Sinnet (Sainte-Justine Hospital, Montreal, QC), whereas samples from 13 adult patients with different types of B leukemia were obtained from the Quebec Leukemia Cell Bank. As a control (CH), we pooled peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from 10 healthy adults. Information relative to each patient is provided in supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The research protocol was approved by Ethic Committees of all concerned institutions.

Mice sample collection

Newborn (≤ 24 hours) NFS mice were injected intraperitoneally with viral particles of Graffi MuLV variant GV-1.4 (1 × 106 PFU) or GV-1.2 (3 × 106 PFU).1 Lymph nodes, thymus, bone marrows, and spleens were harvested from moribund mice for flow cytometry analysis and RNA extraction. All the experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of Quebec (Montreal, QC).

Flow cytometry and cell isolation

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described.1 Cell populations (tumor or control) were purified from the hematopoietic organs by positive selection using magnetic beads coated with the chosen antibody. Leukemic cells were sorted as follow: T cells from the thymus, B cells from the enlarged lymph nodes, and erythroid and megakaryoblastic cells from the infiltrated spleen. Nonleukemic control cells were sorted from a pool of 12 noninfected NFS mice: T cells from the thymus, B cells from the spleen, and erythroblasts and megakaryoblasts from the bone marrow.

RNA isolation, microarray hybridization, and dataset normalization

Total RNA was directly isolated from spleen, thymus, lymph nodes, and bone marrow samples or after cell sorting with the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and purified using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Total RNA (2 μg) from each sample was prepared for hybridization to Affymetrix Gene Chip Mouse Genome 430, Version 2.0 arrays (Genome Quebec Innovation Center). The Affymetrix MicroArray Suite, Version 5.0 was used to scan and quantify the arrays. Normalization of gene expression data was performed using the Bioconductor implementation of Robust Multi Array (B. Bolstad, University of California, Berkeley, CA) available from the Flexarray software Version 1.2, R 2.7.2.6

Microarray data analyses

Using the gene expression profiles obtained from selected leukemias, the Robust Multi Array values of the 45 000 probe sets were used to identify differentially expressed genes. Genes with signal intensity significantly higher (up-regulated) or lower (down-regulated) in leukemias versus control cells (ie, with a 4-fold change in expression levels) were selected. To group microarrays and/or genes based on the high degree of their expression patterns, hierarchical clustering (complete linkage clustering, correlation uncentered) was constructed using GeneCluster software Version 1.6.7 Probe sets selected were further analyzed and the results were treated with the Tree View program. The NetAffx website (Affymetrix) was also used to retrieve gene ontology annotations, probe sequences, and used as a link to Unigene (National Center for Biotechnology Information) for further functional studies. The microarray dataset was deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number GSE12581.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were performed with oligo(dT) as primer using the Omniscript enzyme (QIAGEN) and 100 ng of total RNA. Using an RT reaction corresponding to 10 ng of tumor RNA samples for each selected gene and to 2 ng for actin, the polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed with the Taq polymerase kit (QIAGEN) and the following conditions: 94°C for 3 minutes, 94°C for 45 seconds, 56°C for 45 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. Annealing temperature and number of cycles were optimized for each of the selected 12 genes with specific primers (supplemental Table 2) for semiquantitative analysis. PCR products were analyzed on agarose gel, and band density was quantified with Quantity One Image Software Version 4.4, using the actin gene as an internal control.

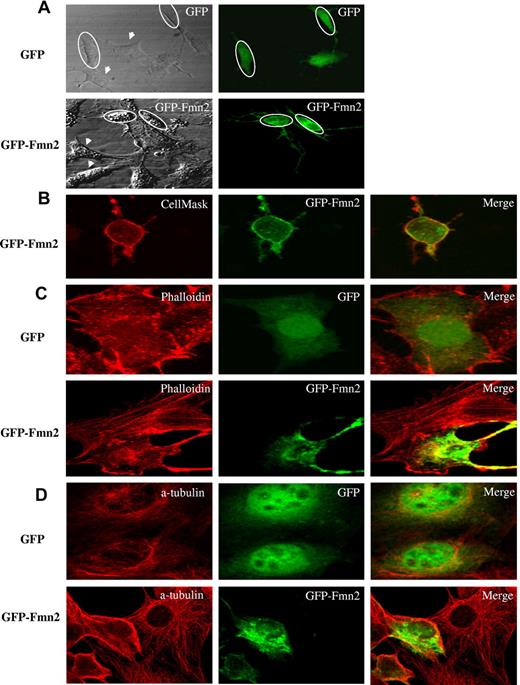

Cellular localization of Fmn2

NIH/3T3 fibroblasts, obtained from ATCC, were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% calf serum, 50 U penicillin, and 50 μg of streptomycin (Invitrogen), 16 hours before transfection. Cells were, respectively, transfected with p-EGFP-N1 (control vector) and GFP-tagged Fmn2 using the polyfect reagent (QIAGEN). Fmn2 localization was analyzed by confocal microscopy 48 hours after transfection. For colocalization, transfected cells were plated on glass coverslips and grown at 50% confluence. Colocalization with the cell surface membrane was determined after cell staining for 5 minutes with 2.5 μg/mL of CellMask Plasma Membrane Stains (Invitrogen) and washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Actin filament staining was performed after cell fixation for 20 minutes with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by PBS washes and permeabilization for 5 minutes with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Cells were incubated 1 hour in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin, washed twice with PBS and the coverslips, and then incubated with 0.3μM of phalloidin coupled to the AlexaFluor-555 (Invitrogen) for 20 minutes. After 2 washes with PBS, coverslips were mounted onto slides using Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and observed within 24 hours by confocal microscopy. For α-tubulin staining, the primary antibody used was a mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich).

Colony formation in soft agar

To determine the anchorage-independent growth, colony formation was tested in soft agar as previously described.8 Briefly, NIH/3T3 cells were transiently transfected with 2.5 μg of empty vector (pCMV), a Ras EJ 6.6, or pCMV-Fmn2 expression vector. After 48 hours, 1 × 104 cells were mixed with melted 0.3% agarose in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium and seeded in 6-well plates on top of a 0.6% agarose base layer containing the same medium. The top layer was covered with 1.5 mL of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium. Cells were fed twice a week for 4 weeks and observed with an optical microscope (40×, Ernst Leitz, 6MBH Wetzlar). Colonies whose size was at least twice larger than that of control colonies were counted.

Results

To better elucidate the cancer signatures of B and T leukemias induced by the murine Graffi virus and to identify new oncogene candidates, a microarray analysis was performed on different types of B and T leukemias induced by this virus compared with nonleukemic B-cell populations (CB1, Cd45R+Cd19+) and T-cell populations (CT1, Cd4+Cd8+). Three B leukemias (B1 and B2, Cd45R+Cd19+; B3, Cd45R+lowCd19+Sca1+) and 3 T leukemias (T1, Cd4+Cd8+; T2, Cd4−Cd8+; and T3, Cd4+Cd8−) were chosen for the microarray experiments (National Center for Biotechnology Information GEO: GSE12581). We were especially interested to identify genes commonly deregulated in these tumors despite their heterogeneity and different stage of differentiation. Hierarchical clustering analyses of genes with a 4-fold change in expression levels compared with control samples were used to obtain a general trend (supplemental Figure 1). This analysis allowed us to group leukemia samples (columns) and/or genes (rows) based on the similarity of their expression level. As a result, T leukemias and B leukemias were clustered separately, making 2 distinguishable groups (supplemental Figure 1). According to these data, Graffi-induced T and B leukemias showed both distinct and common gene expression profiles. Indeed, clustering led to the formation of 6 subgroups representing probe sets either specifically deregulated in B leukemias (188 overexpressed and 86 down-regulated), specifically deregulated in T leukemias (9 overexpressed and 48 down-regulated), or commonly deregulated in both types (8 overexpressed and 32 down-regulated). The complete list of genes presenting these lymphoid signatures is available at: www.biomed.uqam.ca/rassart/microarray2.html.

Gene expression profile specific for pre-B leukemias

We first analyzed the expression profile of genes that could determine the stage of differentiation of the B leukemias. For all B leukemias, Rag2, Vpreb1, Igll1, Enpep, Ebf1, Il7R, Bst1, and Foxp1 were overexpressed compared with control cells (Table 1). Results in this table correspond to the average expression calculated from all samples analyzed in the microarray analysis (B and T controls, B lymphoid, T lymphoid, myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryoblastic tumors). Strong expression of these genes indicated that the 3 Graffi MuLV-induced B tumors were most probably at a pre-B differentiation stage.5,9-15 In all B leukemias, we also detected high levels of Cd79a and Cd79b mRNAs and low levels of Cd20/Ms4a2 mRNA (Table 1). A total of 274 probe sets, corresponding to at least 218 genes, were found highly deregulated in all 3 B leukemias compared with control B lymphocytes. Among these genes, 72 (86 probe sets) were down-regulated and 146 (188 probe sets) were up-regulated (supplemental Figure 1). Several of them had already been associated with B leukemias and are listed in Table 2.

To identify new potential oncogenes associated with the development of pre-B leukemias, we further focused our analysis on 191 probe sets (supplemental Table 3), mostly because they were not yet associated with lymphoid leukemias. Some of them (70 probe sets, including Crisp3 and Lphn2) were already involved in cancer but never associated with B leukemia. Others (72 probe sets) were never associated with cancer, and 36 probe sets had no assigned function. Finally, the 13 remaining probe sets were involved in leukemias other than B leukemias (supplemental Table 3).

Gene expression profile specific for T leukemias

For all analyzed T leukemias, the expression levels of Cd3, Cd4, and Cd8 markers, compared with the other tumor samples (B lymphoid, myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryoblastic tumors), were in accordance with a T lineage immunophenotype (Table 1). Other markers known to be present at the T-cell surface were also detected (Table 1). Among these, Cd6 and Cd28 were the most specific to Graffi-induced T leukemias. We also observed that Cd160 was expressed in all 3 T leukemias but not in double-positive control T cells. Moreover, the 2 Cd8+ tumors (T1 and T2) also expressed Cd7 and Dntt (TdT) (Table 1).

We found that 57 probe sets corresponding to 48 genes showed the same pattern of deregulation in all 3 T leukemias compared with control T lymphocytes (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental Table 3) but not in the B leukemias. Most of them (40 genes) were down-regulated, whereas only 8 were up-regulated.

Nine probe sets were already associated with T leukemias (Table 2), thus validating our approach. Among the remaining 48 probe sets, 15 were associated with other cancers, 5 were related to leukemias other than T leukemias, 20 were neither associated with leukemias nor with other types of cancer, and 8 had no assigned function (supplemental Table 3).

Expression profiles common to both B and T leukemias

The Robust Multi Array analysis also revealed that 57 probe sets (corresponding to 48 known genes) were modulated in both T and B leukemias compared with controls (supplemental Figure 1). These genes may be associated with common characteristics of lymphoid leukemias or common oncogenic features and/or directly related to Graffi leukemogenesis.

Several genes already known to be associated with B and T leukemias were identified (Table 2). Moreover, among the 57 selected probe sets, 36 had never been simultaneously associated to both types of lymphoid leukemias although some were already associated with one type (T leukemia: 10; B leukemia: 4; supplemental Table 3). Among the remaining probe sets, 8 were identified in other cancers, 9 had never been associated with any types of cancer, and 4 remain uncharacterized. Matr3 was the only gene already associated with leukemia (acute myeloid leukemia).

RT-PCR validation

To validate our microarray data, the expression levels of 12 genes specific to either B, T, or to both leukemias (Fmm2, Arntl2, Bfsp2, Gfra2, Gmp6a, Gmp6b, Bmp7, Fbln1, Nln, Mettl1, Etv5, and Celsr1 [Table 3; supplemental Table 3]) were measured by semiquantitative RT-PCR in several Graffi MuLV-induced tumors (pure cell populations, Figure 1; or unsorted cell suspensions, supplemental Figure 2). Significant overexpression of Fmm2, Arntl2, Bfsp2, and Gfra2 was observed in the majority of B leukemias, although being absent in T leukemias confirming their specificity to B leukemias (Figure 1A; Table 3; supplemental Table 3). Gmp6a and Gmp6b, expected to be B leukemia-specific, showed significant overexpression in these tumors compared with the control samples, albeit in only 2 and 3 of the 5 tested B leukemias, respectively. As expected, these 2 genes were not expressed in T leukemias or control samples. High expression levels of Bmp7 were significantly observed in all T leukemias, whereas Fbln1 and Nln were overexpressed in 3 of 5 T leukemias (Figure 1B). Mettl1, expected to be T leukemia-specific gene, was expressed in both T and B leukemias (including controls; Figure 1B). For Etv5, significant higher levels of expression were observed in 4 of 5 B leukemias and 3 of 5 T leukemias (Figure 1C). Finally, Celsr1 was significantly overexpressed in most T leukemias compared with normal control (CT2) but, in contradiction with the microarray data, was poorly expressed in all B leukemias (Figure 1C). Similar validation results were obtained when using Cd19+ splenic cells as normal control instead of Cd45R+ cells (not shown).

Analysis of selected genes differentially expressed in sorted lymphoid leukemia samples. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis in 5 T (T4, Cd4+Cd8+; T5, Cd4+Cd8+; T6, Cd4+Cd8+; T7, Cd4+Cd8+; T8, Cd4+Cd8−) and 5 B (B4, Cd45+Cd19+Sca1+; B5, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B6, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B7, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B8, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+) leukemias. RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate for each gene. The actin gene was used as internal control in specific conditions described in “Semiquantitative RT-PCR” and expression level in each leukemia is presented as a selected gene/actin density ratio. (A) B leukemia-specific genes. (B) T leukemia-specific genes. (C) Genes common to both leukemias. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance, and P less than .05 was considered to be significant (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001) compared with the respective control (B cells from normal spleen [CB2] for the B leukemias and T cells from normal thymus [CT2] for the T leukemias).

Analysis of selected genes differentially expressed in sorted lymphoid leukemia samples. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis in 5 T (T4, Cd4+Cd8+; T5, Cd4+Cd8+; T6, Cd4+Cd8+; T7, Cd4+Cd8+; T8, Cd4+Cd8−) and 5 B (B4, Cd45+Cd19+Sca1+; B5, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B6, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B7, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B8, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+) leukemias. RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate for each gene. The actin gene was used as internal control in specific conditions described in “Semiquantitative RT-PCR” and expression level in each leukemia is presented as a selected gene/actin density ratio. (A) B leukemia-specific genes. (B) T leukemia-specific genes. (C) Genes common to both leukemias. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance, and P less than .05 was considered to be significant (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001) compared with the respective control (B cells from normal spleen [CB2] for the B leukemias and T cells from normal thymus [CT2] for the T leukemias).

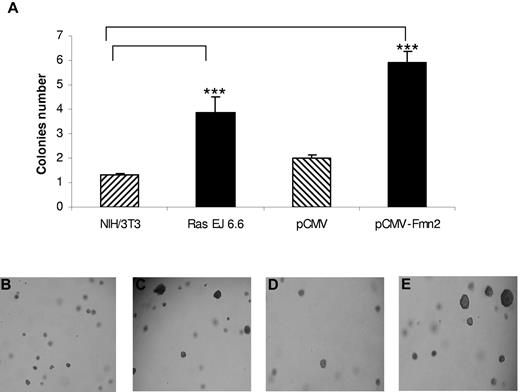

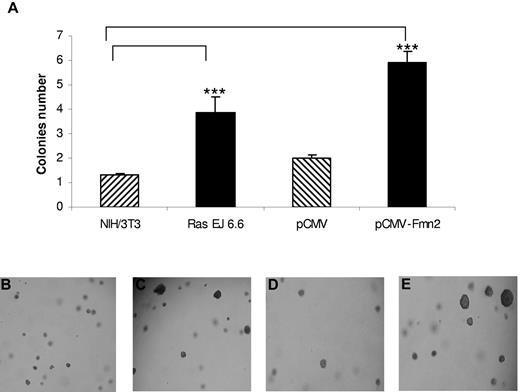

Fmn2 induces anchorage-independent growth

We further focused our interest on Fmn2, a gene specifically overexpressed in B leukemias. This gene is a member of the formin family (FH proteins), and its product is highly conserved among the multidomain proteins involved in a growing range of actin-based processes.16 Most importantly, they may promote cancer cells to become invasive and metastatic through their actin remodeling function.17

We first studied the impact of Fmn2 overexpression on the anchorage-independent growth of NIH/3T3 cells, a classic assay to demonstrate the oncogenic potential of proteins. As shown in Figure 2, the number of larger colonies formed in soft agar was significantly higher in Fmn2-expressing cells compared with control cells and similar in cells expressing the human Ras oncogene (Ras EJ 6.6; Figure 2). These results suggest that the Fmn2 protein confers anchorage independence to NIH/3T3 cells.

Effect of Fmn2 protein expression on anchorage of NIH/3T3 cells. Cells were transiently transfected with pCMV empty vector, with the pCMV-Fmn2 vector, and the Ras (EJ 6.6) expression vector. Transfected or control cells (104) were plated in soft agar as described in “Colony formation in soft agar.” After 4 weeks, the number of colonies (at least twice larger than colonies from controls) was scored (A). The results represent the average of 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (P < .05). Cells were observed with an optical microscope (Ernst Leitz, 6MBH Wetzlar), and representative fields were photographed using a numerical camera (Nikon coolpix 4500; original magnification ×40). Images were analyzed using NIH ImageJ software Version 1.42l. Cells were left untransfected (B) or transfected with Ras EJ 6.6 (C), empty vector (D), or pCMV-Fmn2 (E).

Effect of Fmn2 protein expression on anchorage of NIH/3T3 cells. Cells were transiently transfected with pCMV empty vector, with the pCMV-Fmn2 vector, and the Ras (EJ 6.6) expression vector. Transfected or control cells (104) were plated in soft agar as described in “Colony formation in soft agar.” After 4 weeks, the number of colonies (at least twice larger than colonies from controls) was scored (A). The results represent the average of 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (P < .05). Cells were observed with an optical microscope (Ernst Leitz, 6MBH Wetzlar), and representative fields were photographed using a numerical camera (Nikon coolpix 4500; original magnification ×40). Images were analyzed using NIH ImageJ software Version 1.42l. Cells were left untransfected (B) or transfected with Ras EJ 6.6 (C), empty vector (D), or pCMV-Fmn2 (E).

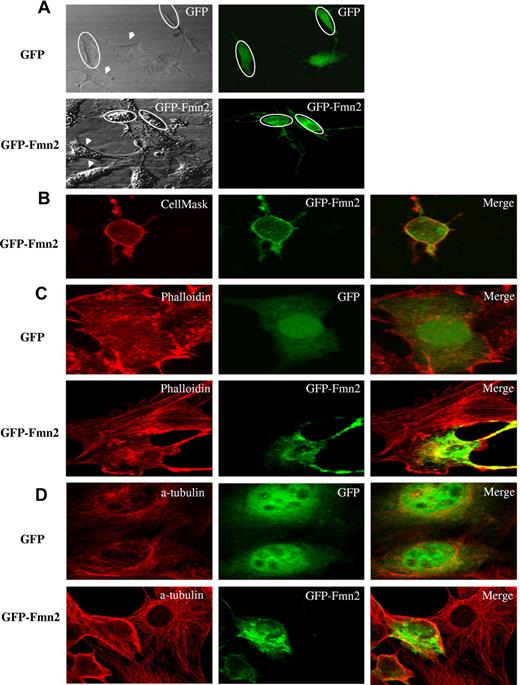

Fmn2 colocalizes with the plasma membrane and disrupts the actin network

We next determined the subcellular localization of Fmn2. When GFP-tagged Fmn2 was transiently expressed in NIH/3T3, the protein was localized at the plasma membrane and within the cytoplasm (Figure 3A). This was further confirmed by colocalization of Fmn2 with a cell membrane marker (CellMask Plasma Membrane Stains; Figure 3B).

Subcellular localization of Fmn2 and its effect on cytoskeleton. The GFP-tagged Fmn2 protein was localized in NIH/3T3 cells and (A) tested for its effect shown on the shape of the cells. (B) Plasma membrane labeling with CellMask. (C) Actin labeling with AlexaFluor-555–conjugated phalloidin. (D) α-tubulin labeling with anti–α-tubulin antibody. Images were captured by a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Bio-Rad MRC-1024 ES) mounted on a Nikon TE-300 using a 60×/1.4 NA oil Plan Apo VC objective, digitally acquired using Laser Sharp software Version 3.2 (Bio-Rad), and analyzed using NIH ImageJ Version 1.42l software. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. The GFP vector alone was used as a control. Ovals and arrows indicate transfected and nontransfected cells, respectively.

Subcellular localization of Fmn2 and its effect on cytoskeleton. The GFP-tagged Fmn2 protein was localized in NIH/3T3 cells and (A) tested for its effect shown on the shape of the cells. (B) Plasma membrane labeling with CellMask. (C) Actin labeling with AlexaFluor-555–conjugated phalloidin. (D) α-tubulin labeling with anti–α-tubulin antibody. Images were captured by a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Bio-Rad MRC-1024 ES) mounted on a Nikon TE-300 using a 60×/1.4 NA oil Plan Apo VC objective, digitally acquired using Laser Sharp software Version 3.2 (Bio-Rad), and analyzed using NIH ImageJ Version 1.42l software. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. The GFP vector alone was used as a control. Ovals and arrows indicate transfected and nontransfected cells, respectively.

We also observed that NIH/3T3 cells expressing Fmn2 showed a reduced size and an abnormal morphology compared with control cells (Figure 3). Moreover, Fmn2-expressing NIH/3T3 cells appeared rounded with long extensions (Figure 3A-D). Actin cytoskeleton is one of the cellular components that maintain cell shape and oncogenic transformation causes profound modifications linked to cell architecture.18-20 Because the overexpression of Fmn2 in NIH/3T3 cells altered their morphology, we first tested the effect of its overexpression on actin filaments and on the microtubule network because of its reported action on actin cables.21 As illustrated in Figure 3C-D, cells overexpressing Fmn2 showed a drastic disruption of the actin and microtubule network and a reduced number of stress fibers compared with control cells.

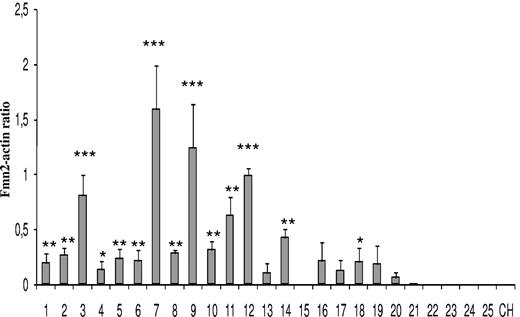

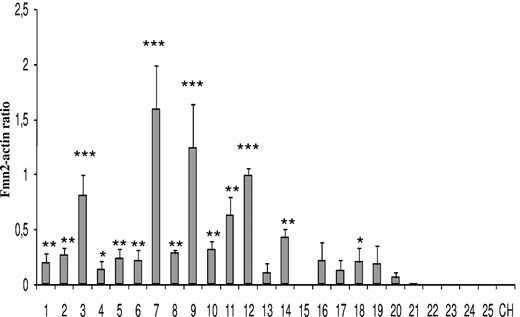

FMN2 gene overexpression in human pre-B leukemia

We measured the expression levels of human FMN2 in patients with different types of B leukemias (Figure 4). No expression was detected by RT-PCR in control samples, in mantle cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. In contrast, FMN2 expression was easily detected in almost all pre-B-ALL patients (L1 and L2; 18 of 19) and in one of 2 Burkitt leukemias. Interestingly, the highest levels of FMN2 were detected in all L1 pediatric pre-B-ALL samples bearing a t(12;21) translocation (lanes 7, 9, 11, and 12). Another tumor (lane 3) also showed high levels of FMN2 expression, suggesting that it could harbor the translocation as well, although this remained to be confirmed.

Expression analysis of human FMN2 gene in different types of B leukemic samples. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed on 12 pediatric pre-B-ALL (lanes 1-12), 7 adult pre-B-ALL (lanes 13-19), 2 Burkitt leukemias (lanes 20 and 21), one mantle cell lymphoma (lane 22), one follicular lymphoma (lane 23), one B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (lane 24), and one chronic lymphocytic leukemia (lane 25). RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate for each gene. The actin gene was used as an internal control as described in “Semiquantitative RT-PCR,” and expression level in each leukemia is presented as a selected gene/actin density ratio. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance, and P less than .05 was considered to be significant (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001) compared with the respective control (CH).

Expression analysis of human FMN2 gene in different types of B leukemic samples. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed on 12 pediatric pre-B-ALL (lanes 1-12), 7 adult pre-B-ALL (lanes 13-19), 2 Burkitt leukemias (lanes 20 and 21), one mantle cell lymphoma (lane 22), one follicular lymphoma (lane 23), one B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (lane 24), and one chronic lymphocytic leukemia (lane 25). RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate for each gene. The actin gene was used as an internal control as described in “Semiquantitative RT-PCR,” and expression level in each leukemia is presented as a selected gene/actin density ratio. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance, and P less than .05 was considered to be significant (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001) compared with the respective control (CH).

Discussion

Graffi MuLV is a good model to gain new insights on leukemia development and progression and to identify new oncogenes. Gene expression profiling of each type of leukemia (T lymphoid, B lymphoid, myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryoblastic) served to identify the cancer signatures of these specific leukemias.5 In this paper, we determined the expression profile of 3 B and 3 T leukemias induced by this retrovirus compared with nonleukemic cell controls (CB and CT, Tables 2, 3; supplemental Table 3) and to nonlymphoid leukemias induced by the same virus (Table 1; www.biomed.uqam.ca/rassart/microarray2.html). Setting the minimal acceptable change in expression levels to 4-fold, we selected 388 probe sets corresponding to 305 genes: 48 genes specifically modulated in T leukemias, 218 in B leukemias, and 40 in both types compared with their respective controls.

Phenotypic properties and cancer signature of B leukemias

Our analysis suggests that B leukemias induced by Graffi MuLV are arrested at the pre-B stage of differentiation based on the high expression of pre-B specific markers (Table 1). As in human pre-B-ALL, these leukemias overexpressed surface markers, such as Cd79a and Cd79b, and lacked Cd20/Ms4a222 (Table 1). These results suggest that data retrieved from the gene profiling analysis of B leukemias should be especially relevant for human pre-B-ALL. Indeed, the results obtained for FMN2 expression in human leukemias are in total agreement with the mouse data.

We selected 218 genes that were specifically deregulated in all 3 B leukemias; and as presented in Table 2, several of these genes were already known to be involved in lymphoid leukemia. This not only validates our microarray analysis but also further defines the cancer signature of these B lymphoid leukemias.

Phenotypic properties and cancer signature of T leukemia

Three distinct T leukemias (T1, Cd4+Cd8+; T2, Cd4−Cd8+; and T3, Cd4+Cd8−) were chosen for the microarray experiments. These 3 different phenotypes are frequently observed in Graffi-induced T leukemias and are also representative of normal T-cell types in healthy mice.1 The retrovirus may have targeted slightly different T-cell blasts or transformed the targeted cells through these slightly different lineages. Based on the analysis, all T leukemias expressed markers specific for the T lineage (Table 1) as well as T-ALL–associated markers, such as Cd7 and Dntt (TdT).23 However, we also found that all 3 T leukemias expressed high levels of Cd160. This marker, normally expressed on human NK and only on a subtype of human CD8+ cells,24 seems to be overexpressed in almost all cases of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia.25

The analysis reveals that a total of 48 genes were strictly modulated in all T leukemias compared with control T cells (Tables 2–3; supplemental Table 3), including 9 probe sets already associated with leukemias. The overall data certainly reveals the existence of a common leukemic gene signature between T leukemias induced by the virus despite heterogeneity and phenotypic differences. We can speculate that similar deregulation patterns observed in these leukemias are associated with common characteristics of T leukemias or common oncogenic properties and are probably found in human T leukemias as well.

Cancer signature common to both B and T leukemias

Because we simultaneously analyzed gene expression profiles of B and T leukemias induced by Graffi MuLV, regardless of lineage differences and tumor heterogeneity, we found that 57 others probe sets modulated in T leukemias were similarly modulated in B leukemias, including 21 previously reported genes (Table 2). These results strongly reinforce the potential of the remaining 36 probe sets to be important for the development of B leukemias. Among these, 23 probe sets had already been associated with either T or B leukemias, with myeloid leukemia or other cancers (supplemental Table 3). These genes are certainly part of the common cancer signature of the T and B lymphoid leukemias and may be relevant for human lymphoid leukemias.

New potential markers and candidate oncogenes from B and T leukemias

The combination of our Graffi-induced tumor model and DNA microarrays allowed us to identify potential new markers of B and T leukemias that could also play an oncogenic role. Among the selected 388 probe sets (at least 305 genes), we further identified 275 genes not yet associated with lymphoid leukemias (supplemental Table 3). Some were specific to B or T leukemias or common to both types, and 124 were obvious oncogene candidates because they had been already associated with nonlymphoid leukemia or other cancers. More interestingly, we identified a total of 103 genes that had never been associated with any type of cancer and 32 probe sets corresponding to uncharacterized genes or genes with unknown function.

By RT-PCR, we have validated changes in the expression levels of 10 of the 12 genes selected according to their specificity for lymphoid leukemias (Figure 1; supplemental Figure 2). Our analysis revealed deregulation of the expression of several genes associated with Graffi MuLV-induced B leukemias (Table 1; Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 2). These genes are Fmm2, Arntl2 (from the bHLH-PAS superfamily involved in regulating cell growth and differentiation26 ), Bfsp2 (a member of the intermediate filament family and component of cytoskeleton proteins in the lens cells, maintaining their morphology and promoting their motility27 ), Gfra2 (from the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor receptor-α family28 and associated with primary neuroblastomas29 and with some medullary thyroid carcinoma tumor cells30 ), and Gmp6a and Gmp6b (members of the myelin proteolipid protein family and neuronal homologues of PLP/DM2031 ).

We also identified several genes that were associated with T leukemias (Figure 1B), namely, Nln (from the metallopeptidase M3 family and involved in the metabolism of neurotensin32 ), Bmp7 (a cytokine from the transforming growth factor-β superfamily and expressed in various types of cancer, including prostate and breast cancers and melanoma33-35 ), and Fbln1 (involved in heart development and in cell signaling involving growth factors36 and associated with human neoplasia, especially breast and ovarian cancers37 ).

Etv5 (a member of the Ets family of transcription factors) was already described in association with B leukemias38 but, according to our data, it appears also overexpressed in T leukemias (Figure 1C). In contrast, the modulation of expression of Celsr1 (involved in the regulation of cell polarity and in convergent extension39 and expressed in gastrointestinal tumors40 ), expected to be specific to both B and T leukemias based on the microarray analysis, was validated in all T leukemic samples (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 2) but in only one B tumor (supplemental Figure 2).

Finally, the high level of expression of Mettl1 (highly expressed in lung cancer41 ) observed by the microarray analysis was not confirmed by RT-PCR (Table 3; supplemental Table 3; Figure 1B) and, as for Celsr1, may reflect a certain degree of tumor heterogeneity as often observed in human leukemias as well.

We also compared gene expression between B tumors and normal B cells from the bone marrow sorted with an anti-Cd45R antibody. This control includes B cells at different stages of maturation. The majority of the tested genes showed results similar to those obtained with spleen the B cells as control except for Fmn2, which was highly expressed in the bone marrow-derived cells (data not shown). Although this had not yet been reported, Fmn2 seems to be normally expressed at an early stage of B-cell lymphopoiesis in the bone marrow. Its expression decreases when B cells move from the bone marrow to the spleen for maturation. This inverse correlation between the expression level of Fmn2 and B-cell maturation does not necessarily contradict its involvement in carcinogenesis. This is exemplified with GATA2, which is essential for the maintenance and the proliferation of hematopoietic progenitors during normal hematopoiesis42 while having been implicated in tumorigenesis.

Overall, these results strongly suggest that the majority of the 275 selected probe sets, in particular Fmn2, Arntl2, Gpm6a, Gpm6b, Bfsp2, Gfra2, Nln, Bmp7, Fbln1, and Etv5, are potentially new specific markers or oncogenes for B, T, or B and T leukemias. Our analysis also identified several down-regulated genes, such as Klk6 and TgfβI (Table 2), which are already identified as tumors suppressors. Further studies are required to determine whether the modulation of expression also correlates with changes at the protein level and most importantly to determine their potential role in human leukemias. Regarding Fmn2, our attempts to measure levels of this protein in mice tumors was hampered by the lack of specific antibodies.

Fmn2 gene is a good candidate oncogene

Among the 10 genes validated by RT-PCR, we further characterized Fmn2, which was specifically associated with B leukemias. Fmn2 is expressed in the developing and mature central nervous system43 and in oocytes.16 It was identified as a formin homology (FH) gene and the protein contains 2 characteristic FH protein domains: FH1 (proline-rich region) and FH2. The latter is responsible for actin nucleation.44 The comparison of the mouse and human Fmn2 showed 74.7% sequence homology. Members of the formin family are implicated in cytokinesis, organogenesis, and normal tissue homeostasis but are also involved in the invasive potential of cancerous cells and metastasis.17 The implication of Fmn2 in the development of tumors had not yet been demonstrated, even though human FMN2 ESTs were found in several human tumors (parathyroid tumor, glioblastoma, retinoblastoma, and chondrosarcoma).17

In this paper, we report, for the first time, that Fmn2 is not only specifically overexpressed in B leukemias induced by the Graffi virus in mice (Figure 1; Table 3; supplemental Table 3) but more importantly in human pre-B-ALL (Figure 4).

Moreover, we demonstrate that ectopic expression of Fmn2 confers anchorage-independent growth to NIH3T3 cells (Figure 2). This anchorage-independent growth conferred by Fmn2 is probably related to its ability to induce the disruption of the actin and microtubule network and a reduction of the number of stress fibers. The biologic role of Fmn2 in actin and microtubule network disruption in B leukemia is not quite clear. However, we are convinced that the up-regulation of FMN2 expression could disturb the dynamic of the actin network of ALL cells accompanied by the reorganization of their cytoskeleton, which in turn could contribute to their abnormal behaviors. Some examples highlight the fact that even B cells change form depending on their state of development or their abnormal behaviors. Indeed, it was reported that during spreading, the B lymphocyte cytoarchitecture is converted from a semirigid (before migration) to a more flexible state (during migration). This migration seems to involve up-regulation of CD44 adhesion molecule on activated B lymphocytes and to require the rearrangement of many cytoskeleton components (actin, microtubules, and vimentin).45 In addition, Caligaris-Cappio et al demonstrated that cells from B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia or hairy cell leukemia (HCL) showed an aberrant cytoskeleton organization.46 In addition, Schmitt-Gräff et al observed changes in the F-actin in B cells of patients with ALL.47

Implication of FMN2 in human pre-B-ALL

To determine the possible contribution of human FMN2 to leukemogenesis, we measured its expression in 25 different B leukemia samples. We showed that this gene was specifically overexpressed in L1 and L2 pre-B-ALL (18 of 19 of cases; Figure 4), thereby agreeing with our microarray data (Table 1). More importantly, we show that 4 pediatric pre-B-ALL samples with a t(12;21) translocation produced the strongest signals. Such t(12;21) rearrangement involving the TEL/AML1 genes is more frequent in childhood ALL (25%–30%) with a B-precursor phenotype than in adult ALL (3%–5%).48 Although this translocation is associated with a favorable outcome and a good response to conventional chemotherapy, 25% of relapses occur off-therapy and require additional therapeutic strategies. The strong expression of FMN2 in pediatric pre-B-ALL with the t(12;21) translocation suggests that the TEL/AML1 fusion protein could directly or indirectly up-regulate FMN2 gene expression. Together, these results suggest that very high expression of FMN2 in pre-B-ALL could be correlated with a t(12;21) translocation and could be used as marker, although this has to be confirmed with a larger panel of samples.

In conclusion, we identified a set of genes that are specific markers for B and T leukemias induced by the Graffi MuLV and thus may also serve as potential markers in human lymphoid leukemias. Some of these genes may have oncogenic properties as revealed with the mouse Fmn2 gene. For the first time, we show that FMN2 is up-regulated in human pre-B-ALL and more specifically in pediatric pre-B-ALL with the t(12;21) translocation. Additional investigations are necessary to further characterize its function in tumor induction.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Daniel Sinnet for providing pediatric tumor samples; André Ponton, Michal Blazejczyk, and Mathieu Miron from Genome Quebec Innovation Center (Montreal, QC) for help with the design and analyses of the microarray experiments; Dr Benoit Barbeau for critical reading of the manuscript; and Denis Flipo for help with the confocal microscopy analysis.

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant MOP-37994; E.R.). C.C. is a recipient of a studentship from the Tunisia Government and Fondation UQAM.

Authorship

Contribution: E.R. and V.V. designed the microarray experiments; V.V. performed the microarray experiments; C.C. analyzed the microarray data of the lymphoid leukemias and performed the experiments; L.-C.L. contributed to some experiments and helpful discussions; C.C., E.E., and E.R. wrote the manuscript; and E.E and E.R. supervised the overall project.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Eric Rassart, Département des Sciences Biologiques, Université du Québec à Montréal, Case Postale 8888 Succursale Centre-ville, Montréal, QC, H3C-3P8, Canada; e-mail: rassart.eric@uqam.ca; and Elsy Edouard, Département des Sciences Biologiques, Université du Québec à Montréal, Case Postale 8888 Succursale Centre-ville, Montréal, QC, H3C-3P8, Canada; e-mail: edouard.elsy@uqam.ca.

![Figure 1. Analysis of selected genes differentially expressed in sorted lymphoid leukemia samples. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis in 5 T (T4, Cd4+Cd8+; T5, Cd4+Cd8+; T6, Cd4+Cd8+; T7, Cd4+Cd8+; T8, Cd4+Cd8−) and 5 B (B4, Cd45+Cd19+Sca1+; B5, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B6, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B7, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B8, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+) leukemias. RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate for each gene. The actin gene was used as internal control in specific conditions described in “Semiquantitative RT-PCR” and expression level in each leukemia is presented as a selected gene/actin density ratio. (A) B leukemia-specific genes. (B) T leukemia-specific genes. (C) Genes common to both leukemias. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance, and P less than .05 was considered to be significant (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001) compared with the respective control (B cells from normal spleen [CB2] for the B leukemias and T cells from normal thymus [CT2] for the T leukemias).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/6/10.1182_blood-2010-10-311001/4/m_zh89991066160001.jpeg?Expires=1771159820&Signature=qrdcGmYc4pTRx8HN-B~xVbPpBHuxXnDi17e1S~VLSMk1x7VDC6WaFgPg-UaoqxKhZ~-ueXaEHaa8AclK5IWyiwlKGt5KjOXTJ-Z19SCgq9qaqpU68qvAipszRp68Mb-vmZq4kMvZ~aLUzeX042yrgelCZHt1g~k3qwBiQIovc-iGCLNsf4tw7hfCkjs5OLzx3f6im--Yjlh1p4m8PtJPad0IYYFnNfe1hNyvPVYCG98qWMFlQC8zzMm1vlgmt0KJii-RzUjdA66vdwrxIu5bjqq9VT~Y1yWpZiLC8yKULKjfi6DGAPYT6QRq1q1Y1vd0USxd478yFLW31JATJ5Q19A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. Analysis of selected genes differentially expressed in sorted lymphoid leukemia samples. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis in 5 T (T4, Cd4+Cd8+; T5, Cd4+Cd8+; T6, Cd4+Cd8+; T7, Cd4+Cd8+; T8, Cd4+Cd8−) and 5 B (B4, Cd45+Cd19+Sca1+; B5, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B6, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B7, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+; B8, Cd45R+Cd19+Sca1+) leukemias. RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate for each gene. The actin gene was used as internal control in specific conditions described in “Semiquantitative RT-PCR” and expression level in each leukemia is presented as a selected gene/actin density ratio. (A) B leukemia-specific genes. (B) T leukemia-specific genes. (C) Genes common to both leukemias. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance, and P less than .05 was considered to be significant (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001) compared with the respective control (B cells from normal spleen [CB2] for the B leukemias and T cells from normal thymus [CT2] for the T leukemias).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/117/6/10.1182_blood-2010-10-311001/4/m_zh89991066160001.jpeg?Expires=1771205177&Signature=s8l4gjlr7XteKRVWQk9THmcEQscKJFTQ7H9rC-3075SfzzqO-DQ2JJU--vRRwm1y348DGzZBn-tnC-cGe9wC9cwb5-Q4uOkx3ieG866RuLrt7zURXz8hKeBDMBPTJ-S1EEHvmbUDzcWnhm9WLWdiCvMopIAmIsBOsfGUNEONLhQQr-SZ-ySvwB8dXFWF2btTIXNw9rAg68~I2B4EbmVP034HMavZWi6gn54ygdwFbRF95u0Irv6voefjkWcaleiyGaczdvXm2hBgeDvhDjLJLX2N9IBcNf1s4FPYX2f0fXAmflpU08t05csE8j2rQFWFcFfk8e6C8DsjBZiyXTUfxA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)