To the editor:

We read with interest the article by Metzelder et al showing sorafenib had antileukemic activity and could be given safely to patients with FLT-3 mutated AML relapsing after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT).1 Because sorafenib delays progression of renal cell carcinoma, we administered this drug to patients who had progression of metastatic kidney cancer after an ASCT. Besides the classic sorafenib hand-foot syndrome, we also observed new-onset, biopsy-confirmed chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) of the skin (including one case of sclerodermoid cGVHD) and exacerbations of preexisting chronic skin GHVD in 4 of 7 patients treated with 400 mg of sorafenib given orally twice daily. Metzelder et al also noted cGVHD occurred in 2 of 4 patients receiving sorafenib after ASCT, although the temporal association of this drug with cGVHD is unclear from their study. Although the authors speculate sorafenib might be effective when given prophylactically after an ASCT to reduce FLT-3 mutated AML leukemia burden, it is important to note that the initiation of sorafenib in the 4 patients in their study was delayed months after the transplantation (87-322 days). In vitro and murine findings from our laboratory raise the concern that sorafenib may result in substantial toxicity and increase the risk of GVHD when this drug is administered early after a T cell–replete ASCT.

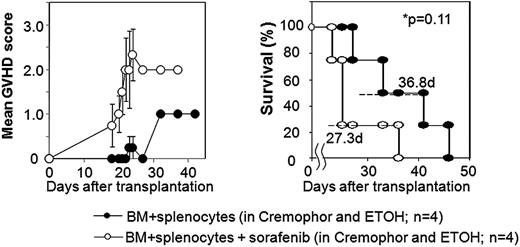

Using a major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–matched murine model of ASCT, we explored whether sorafenib would slow tumor progression potentially facilitating GVT effects in mice with established RENCA tumors. Balb/C mice conditioned with 950cGy total body irradiation received either a T cell–depleted (bone marrow alone) or T cell–replete (bone marrow plus splenocytes) ASCT from MHC-matched, minor antigen–mismatched B10.d2 donors. Nontransplanted tumor-bearing Balb/C control mice that received sorafenib by oral gavage (60 mg/kg/day) had no evidence of drug toxicity and had slower tumor growth which improved survival compared with mice not receiving sorafenib (median survival 49 vs 34 days, respectively; P = .04). In recipients of a T cell–depleted ASCT, sorafenib by oral gavage was not associated with overt toxicities and also delayed tumor progression and improved survival compared with nonsorafenib controls (median survival 42 vs 31 days; P < .01). Remarkably, T cell–depleted transplant recipients that received sorafenib had no evidence of organ toxicity or GVHD at autopsy. In contrast, there was a surprising and significant increase in clinical GVHD (Figure 1) and histologically confirmed severe skin and liver GVHD (P = .0023) with a trend toward shortened survival when sorafenib was administered to recipients of a T cell–replete SCT (Figure 1). Blood samples showed a nonsignificant increase in the percentage of CD3+ T cells in mice that received a T cell–replete ASCT with sorafenib versus without sorafenib (62% ± 29% vs 28% ± 10%; P = .26).

Sorafenib worsens GVHD and shortens survival when given after a T cell–replete allogeneic SCT in mice with RENCA tumors. GVHD score and survival in tumor bearing mice undergoing allogeneic SCT using BM + splenocytes with or with sorafenib given by oral gavage after transplantation. GVHD score was assessed by the following symptoms: alopecia (0-4 points), hunched posture (0-2 points), ear or eye irritation (0-1 points). Error bars (left panel) show standard error of the mean.

Sorafenib worsens GVHD and shortens survival when given after a T cell–replete allogeneic SCT in mice with RENCA tumors. GVHD score and survival in tumor bearing mice undergoing allogeneic SCT using BM + splenocytes with or with sorafenib given by oral gavage after transplantation. GVHD score was assessed by the following symptoms: alopecia (0-4 points), hunched posture (0-2 points), ear or eye irritation (0-1 points). Error bars (left panel) show standard error of the mean.

Although the exact mechanism through which this agent enhances GVHD in vivo remains under investigation, correlative in vitro studies using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from healthy volunteers revealed OKT3-induced T-cell proliferation increased significantly in the presence of sorafenib (median stimulation index 4.6; range, 1.8-10.8; P = .035). These preclinical murine studies and early observations in humans raise the concern that sorafenib may exacerbate GVHD, and imply the early or prophylactic use of this agent after a T-cell replete ASCT for FLT-3-ITD–positive AML should be pursued with caution and should be given only in the context of a clinical trial.

Authorship

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Richard Childs, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, 10 Center Dr, Bldg 10, CRC Rm 35330, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: childsr@nih.gov.

Reference

National Institutes of Health