Abstract

Both extrinsic and intrinsic mechanisms tightly govern hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) decisions of self-renewal and differentiation. However, transcription factors that can selectively regulate HSC self-renewal division after stress remain to be identified. Slug is an evolutionarily conserved zinc-finger transcription factor that is highly expressed in primitive hematopoietic cells and is critical for the radioprotection of these key cells. We studied the effect of Slug in the regulation of HSCs in Slug-deficient mice under normal and stress conditions using serial functional assays. Here, we show that Slug deficiency does not disturb hematopoiesis or alter HSC homeostasis and differentiation in bone marrow but increases the numbers of primitive hematopoietic cells in the extramedullary spleen site. Deletion of Slug enhances HSC repopulating potential but not its homing and differentiation ability. Furthermore, Slug deficiency increases HSC proliferation and repopulating potential in vivo after myelosuppression and accelerates HSC expansion during in vitro culture. Therefore, we propose that Slug is essential for controlling the transition of HSCs from relative quiescence under steady-state condition to rapid proliferation under stress conditions. Our data suggest that inhibition of Slug in HSCs may present a novel strategy for accelerating hematopoietic recovery, thus providing therapeutic benefits for patients after clinical myelosuppressive treatment.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are rare self-renewing, multipotential cells localized within the osteoblastic and vascular niches of adult bone marrow (BM).1,2 In adult BM, the earliest multipotent stem cells sequentially give rise to phenotypically and functionally defined long-term self-renewing HSCs (LT-HSCs), short-term self-renewing HSCs (ST-HSCs), and multipotent progenitors (MPPs) without the capacity for self-renewal. In addition to maintaining the HSC pool, HSCs extensively proliferate and differentiate into myeloid and lymphoid lineages to continuously replenish mature blood cells throughout a person's lifetime.

The introduction of mutant alleles in mice by gene targeting provided insight into the function of positive and negative regulators of HSCs. As extrinsic regulators, many cytokines and their receptors regulate HSC self-renewal and differentiation.3-5 Intrinsic regulators including transcriptional factors such as Ikaros, Hox, and Bmi-1, and also cell cycle regulators including p21, p27, and c-Myc are implicated in the maintenance of HSCs quiescence under steady-state conditions.6 Interestingly, the transcriptional factor Gfi1, which shares a SNAG repression domain with Slug/Snail family members, is critical for restricting proliferation and preserving the functional integrity of HSCs.7,8

Slug belongs to the highly conserved Slug/Snail family of zinc-finger transcription factors found in diverse species ranging from Caenorahbditis elegans to humans. Mammalian members of this family include Snail1 Slug/Snail2, Snail3/Smuc, and Scratch. These members all share an extreme N-terminal SNAG domain that is necessary for transcriptional repression and their nuclear localization. In addition, they share a highly conserved carboxy-termini containing from 4 to 6 C2H2-type zinc fingers that is required for binding to a subset of E-box (ACAGGTG) site.9 Slug/Snail transcription factors are implicated in many pathways during development, such as cell-fate determination in the wing, mesoderm formation, and central nervous system development in Drosophila.10 Slug/Snail proteins are also involved in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of mesodermal cells,11 the migration of neural crest cells,12 and the protection of hematopoietic cells against apoptosis.13,14 In addition, these factors play essential roles in carcinogenesis and tumor metastasis.15-17 It was shown that elevated expression of Slug/Snail down-regulates the adhesion molecule E-cadherin, resulting in tumor progression.18,19

Slug-deficient mice were independently generated by the laboratories of Drs Thomas Look and Thomas Gridley; these mice are viable and fertile and exhibit growth retardation after birth and eyelid malformations.20 Although peripheral blood counts and lymphoid subsets in Slug-deficient mice appeared normal, they are very sensitive to γ-irradiation.13 We previously demonstrated that Slug is selectively expressed in HSCs and protects mice from sublethal doses of radiation by enhancing survival of myeloid progenitor cells through inhibiting the mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathway.14

In this study, we investigated the effects of Slug on the regulation of hematopoiesis under normal and stress conditions by serial functional assays, including the colony-forming unit-spleen (CFU-S), competitive repopulating (CRU) assays, serial BM transplantation, and cell proliferation analysis. We present evidence that Slug negatively regulates the repopulating potential of primitive hematopoietic cells under stress condition.

Methods

Experimental animals

Slug−/− mice were generated as described previously9 and were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 (CD45.2) background for more than 6 generations. Mice (Slug−/−, Slug+/−, and Slug+/+) were used for all the experiments when they were at 6 to 8 weeks of age. All mice studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute.

Phenotypic analysis of BM cells by flow cytometry

Phenotypic analysis of LSK cells (Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+) was performed according to the previous reports.21 Briefly, 106 BM mononuclear cells (MNCs) were stained with a mixture of biotinylated antibodies against mouse CD3e, CD4, CD8, CD45/B220, Gr-1, Mac-1, and TER-119. Subsequently, the cells were costained with streptavidin–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti–Sca-1–phycoerythrin (PE), and anti–c-Kit–allophycocyanin (APC).

For analysis of Flk2−LSK cells (Flk2−Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+), 106 BM MNCs were sequentially incubated with the biotinylated lineage antibodies, streptavidin-FITC, anti–Sca1-PE/Cy7, anti–c-Kit–APC/Cy7, and anti–Flk2-PE.22 For analysis of Ki-67+LSK cells, BM MNCs were stained with anti–Sca-1-PE and anti–c-Kit-APC, with the addition of Lin panel− PE-Cy5.5 antibodies. The stained cells were washed and then stained with Ki-67 antibody, according to the recommended procedure.23

For analysis of BM MNCs with SLAM antibodies, the cells were costained with anti–CD150-Alexa647, anti–CD48-PE, and anti–CD244-FITC.24 HSCs (CD150+CD48−CD244−), MPP cells (CD150−CD48−CD244+), and lineage-restricted progenitors (LRPs, CD150−CD48+CD244+) were identified by flow cytometric analysis.24 For EPCR+ HSC phenotype, anti-EPCR-PE antibody (StemCell Technologies) was used, according to a previous report.25

For lineage phenotype, BM MNCs were stained on ice with anti-CD3, anti-B220, anti–Mac-1-(M1/70), and anti–Gr-1 antibodies. For all the staining, Fc block (2.4G2) was included to inhibit nonspecific binding, and 7-amino-actinomycin D was included to exclude dead cells during flow cytometric analysis. All antibodies, unless stated, were otherwise purchased from BioLegend and eBioscence. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur or FACSAria, and all flow cytometric data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Progenitor cells assays: CFU-S BM and side population

A CFU-S assay was performed using BM and spleen day 16 CFU-S–derived cells, as described by Till and McCulloch.26 A total of 8 × 104 BM or spleen cells were transplanted in lethally irradiated mice.

BM transplantation

We used 8- to 12-week-old B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ (The Jackson Laboratory), a congenic C57BI/6 strain (CD45.1), as recipients for BM transplantation experiments. Competitive BM cells were isolated from F1 generation of CD45.1 × CD45.2 strains. For BM transplantation experiments, the recipient mice (4-8 weeks old) were given acidified antibiotic water (1.1 g/L neomycin sulfate and 106 U/L polymyxin B sulfate) 3 days before γ-irradiation and then lethally irradiated with 9 Gy total body irradiation or a total of 13 Gy (given in 2 fractions of 6.5 Gy, 3 hours apart) before BM transplantation by retro-orbital injection. Recipients were continuously fed with acidified antibiotic water for 30 days to reduce the chance of spontaneous infection. Ionizing radiation was performed in a 137Cs γ-ray Model 143-45 irradiator (J.L. Shepherd and Associates) at a rate of 109 cGy/min with the indicated doses.

Homing assay for primitive hematopoietic cells

Homing assay was established on the basis of CD45.1 and CD45.2 allotypes. Test BM cells were prepared from Slug−/− or Slug+/− control mice and mixed with an equal number (1 × 107) of competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+), respectively. The mixed cells were analyzed for the ratio of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in test (CD45.2+) versus competitor (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) BM cells, and then injected into 2 groups of lethally irradiated recipient mice that were irradiated 72 hours before transplantation. Sixteen hours after injection, total BM cells were isolated from recipients and analyzed for the ratio of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in injected test versus competitor BM cells (percentage of CD45.2+ Lin−Sca-1+ cells to percentage of CD45.1+/CD45.2+ Lin−Sca-1+ cells).

CRU assay

CRU assay is often used to measure the frequency of HSCs. This assay is also called the limit-dilution competitive repopulation assay.27,28 Briefly, 3 cell doses (5 × 104, 2 × 105, and 1 × 106) of test donor BM cells isolated from Slug−/− and Slug+/− control mice were competed against a constant dose (2 × 105) of competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+). Ten irradiated recipient mice were transplanted for each group. Peripheral blood in each recipient was analyzed for the engraftment level of donor cells at 2 and 4 months after BM transplantation, using anti-CD45.1 and anti-CD45.2 antibodies. Anti-CD3e (145–2C11), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti–MAC-1-(M1/70), and anti-Gr-1(RB6-8C5; eBioscence) were used for lineage analysis. In each animal, 1% or more of CD45.2+ cells containing T, B, and myeloid cells was defined as positive engraftment. The number of mice negative for reconstitution in each cell dose was measured, and frequency of HSCs was estimated using Poisson statistics29 (L-Calc software; StemCell Technologies). Animals that died during the course were excluded and not counted in the limiting dilution analysis.

Competitive BM transplantation coupled with serial transfer

Equal numbers of BM MNCs (5 × 106) from Slug−/− or Slug+/+ mice were mixed with freshly isolated wild-type competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) at a 1:1 ratio and transplanted into the lethally irradiated recipients (CD45.1+) by retro-orbital injection. For the secondary BM transplantation, BM cells (1 × 107) were prepared from primary recipient mice 2 months after BM transplantation, and secondarily transplanted into new irradiated recipients (CD45.1+). For the tertiary BM transplantation, CD45.1+-recipient mice were transplanted with BM MNCs (5 × 106) isolated from the secondary recipients at 2 months after the secondary BM transplantation. BM cells were harvested from the primary, the secondary, and the tertiary recipient mice and analyzed by flow cytometry.

HSC proliferation and HSC repopulating potential in vivo after 5-FU treatment

Annexin V apoptosis assay

For analysis of apoptotic HSCs, BM cells were harvested from Slug−/− and Slug+/+ mice at different time points after 5-FU treatment. BM cells were stained with biotinylated antibodies specific for lineage markers, PE-anti–Scal-1, FITC-anti–c-Kit, and followed by Avid-PE-Cy5.5 staining. The stained cells were further stained with APC—annexin V according to the manufacturer's instruction (Biotium). Annexin V+Lin−Sca-1+ cells were gated as apoptotic HSCs.

Cell-cycle analysis by the Edu incorporation assay

BM cells were harvested from Slug+/+ and Slug−/− mice at 5 days after a single injection of 5-FU at 300 mg/kg body weight. The suspended cells were incubated with 10μM Edu (Invitrogen) in the StemSpan SFEM medium (StemCell Technologies) containing 1 ng/mL stem cell factor (SCF) and thrombopoietin (TPO), at 37°C for 90 minutes. After incubation, the cells were first stained with biotinylated-lineage cocktail antibodies, as described previously. Lineage-positive cells were depleted using MACS Anti-Biotin MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec), and the cell surface was then stained with anti–Sca-1–APC (eBioscience). Cells that were incorporated with Edu were labeled with AlexaFluor 488 using the Click-iT EdU Flow Cytometry Assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Edu+Lin−Sca-1+ cells were determined by flow cytometric analysis.

Results

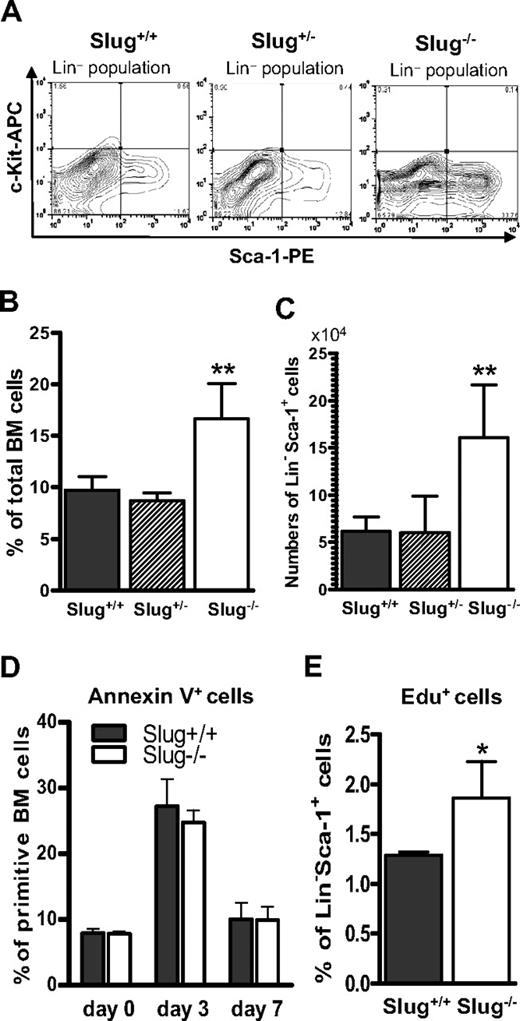

Normal differentiation and proliferation of HSCs in Slug−/− mice under normal condition

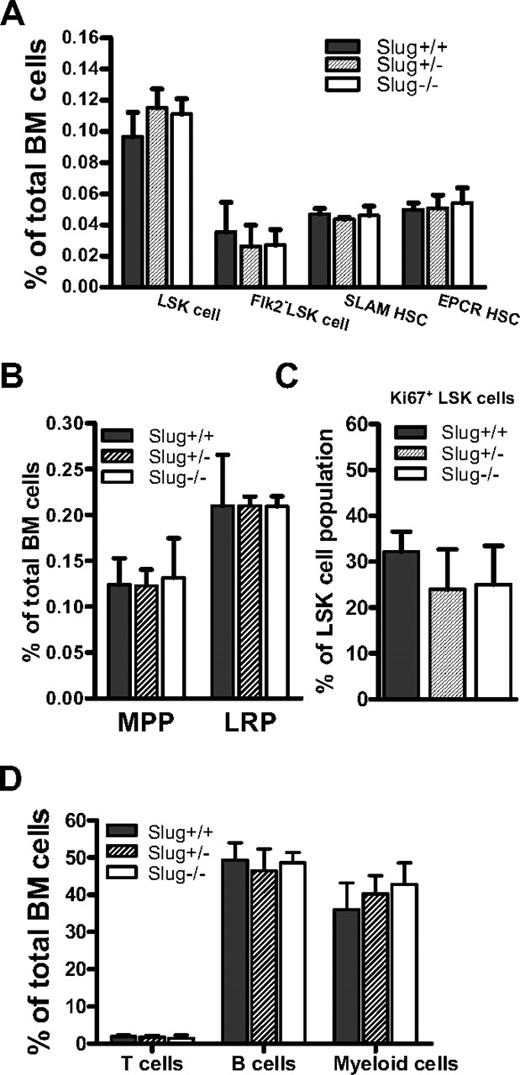

Although we previously showed that the development of myeloid progenitor cells was not impaired in Slug-deficient mice,14 it remains to be determined whether or not Slug interferes with the frequencies of HSCs and progenitors. To this end, we analyzed HSCs and progenitors in the BM of Slug+/+, Slug+/−, and Slug−/− mice using fluorescence-labeled antibodies and flow cytometric analysis. Our data indicated that the percentage of LSK, Flk2−LSK (Flk2−Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+), SLAM (CD150+CD48−CD244−), and EPCR+ HSCs is comparable, regardless of the Slug genotype (Figure 1A). In addition, we found that the percentage of MPPs and LRPs (lineage-restricted progenitors, CD150−CD48+CD244+) is similar in BM cells of Slug−/−, Slug+/−, and wild-type littermates (Figure 1B).

Deletion of Slug does not disturb homeostasis of primitive hematopoietic cells in BM of mice. (A) The frequencies of LSK cells, Flk2− LSK HSCs, SLAM (CD150− CD48+ CD244+) HSCs, and EPCR+ HSCs as a percentage of total BM mononuclear cells in Slug+/+ mice (n = 5), Slug+/− mice (n = 5), and Slug−/− mice (n = 5). (B) The percentage of MPP (CD150−CD48−CD244+) and LRPs (CD150−CD48+CD244+) in BM of Slug+/+ mice (n = 5), Slug+/− mice (n = 5), and Slug−/− mice (n = 5). (C) The frequencies of Ki-67+ cells in LSK cell populations in Slug+/+ mice (n = 5), Slug+/− mice (n = 5), and Slug−/− mice (n = 5). (D) The frequencies of T, B, and myeloid cells in Slug+/+ mice (n = 5), Slug+/− mice (n = 5), and Slug−/− mice (n = 5). Data shown were the mean ratio ± SD. There is no significant difference for each type of cells in Slug+/+ mice vs Slug+/− mice vs Slug−/− mice.

Deletion of Slug does not disturb homeostasis of primitive hematopoietic cells in BM of mice. (A) The frequencies of LSK cells, Flk2− LSK HSCs, SLAM (CD150− CD48+ CD244+) HSCs, and EPCR+ HSCs as a percentage of total BM mononuclear cells in Slug+/+ mice (n = 5), Slug+/− mice (n = 5), and Slug−/− mice (n = 5). (B) The percentage of MPP (CD150−CD48−CD244+) and LRPs (CD150−CD48+CD244+) in BM of Slug+/+ mice (n = 5), Slug+/− mice (n = 5), and Slug−/− mice (n = 5). (C) The frequencies of Ki-67+ cells in LSK cell populations in Slug+/+ mice (n = 5), Slug+/− mice (n = 5), and Slug−/− mice (n = 5). (D) The frequencies of T, B, and myeloid cells in Slug+/+ mice (n = 5), Slug+/− mice (n = 5), and Slug−/− mice (n = 5). Data shown were the mean ratio ± SD. There is no significant difference for each type of cells in Slug+/+ mice vs Slug+/− mice vs Slug−/− mice.

Because HSCs are normally maintained in a quiescent state (G0 phase), HSC long-term self-renewal capacity is preserved in vivo. Therefore, we examined the proliferating status of LSK cells using the specific antibody against Ki-67, which is strictly expressed by proliferating cells in all phases of the active cell cycle (G1, S, G2, and M phase), but absent in resting (G0) cells. We found that Slug-deficient mice have a similar number of proliferating (Ki-67+) LSK cells, compared with Slug+/− and Slug−/− mice (Figure 1C).

In addition, we analyzed differentiated cells in Slug+/+, Slug+/−, and Slug−/− mice. In agreement with previous findings,13,14 these mice also had an equivalent number of T, B, and myeloid cells in their peripheral blood (Figure 1D). Collectively, these data indicated that Slug-deficient mice have normal levels of HSCs, hematopoietic progenitor cells, and terminally differentiated hematopoietic cells. Thus, Slug is dispensable for normal hematopoiesis under normal conditions.

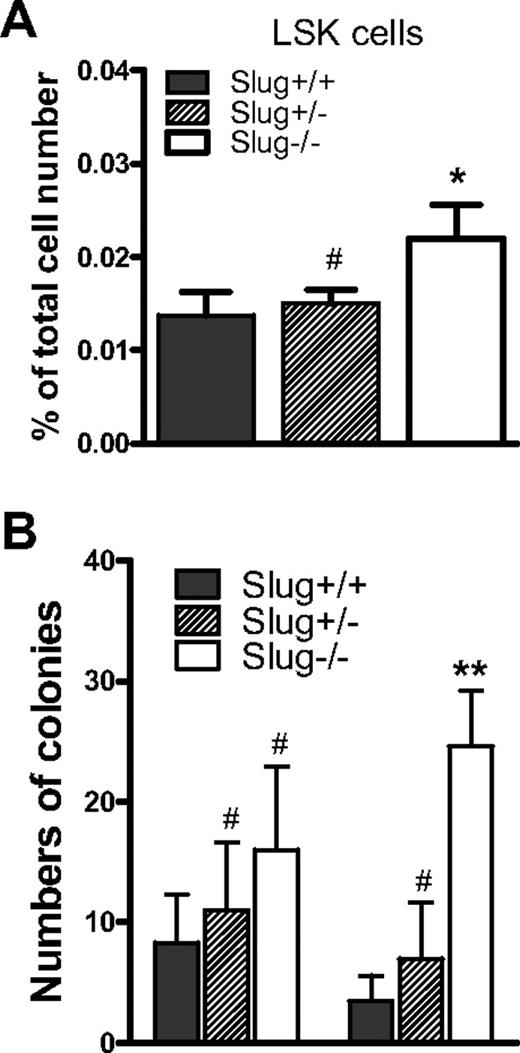

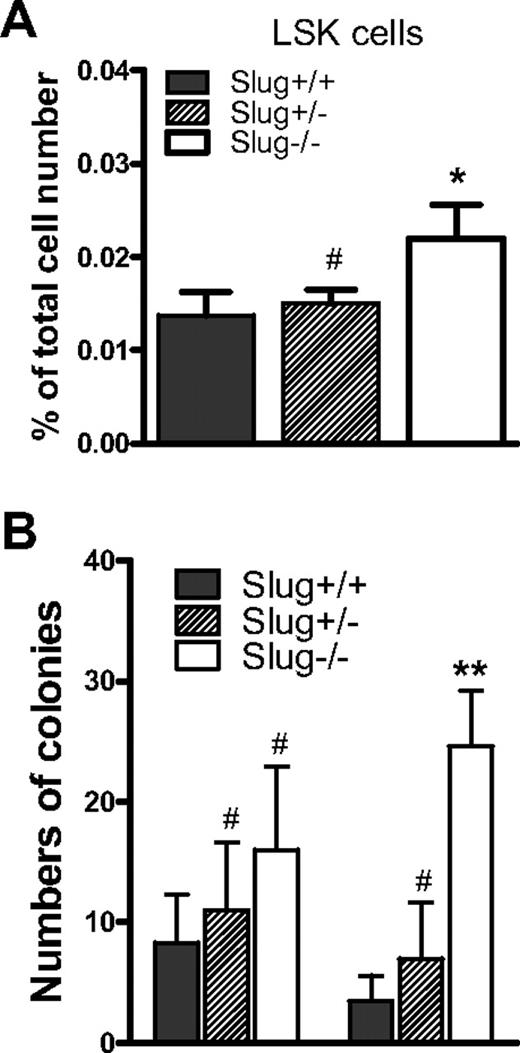

Deletion of Slug leads to elevated numbers of extramedullary CFU-S colonies

Although our data indicated that Slug deficiency does not affect HSC frequency and interfere with normal hematopoiesis in BM under normal condition (Figure 1), it was previously shown that the numbers of hematopoietic colony-forming progenitors (BFU-E, CFU-E, CFU-GM, and CFU-Meg) in spleen were 4-fold higher in Slug−/− mice than Slug+/+ control mice.13 These data suggested that the lack of Slug might affect the retention of HSCs in the BM and promote migration of HSCs from their BM niches1,2 to the spleen. To test this possibility, we used flow cytometric analysis to examine HSC (LSK cell) frequency in the spleen, in addition to the BM. We used quantitative CFU assays to functionally assess the numbers of HSCs by measuring CFU-S colonies.26 We found that the frequency of LSK cells in spleen cell population is 2-fold higher in Slug−/− mice than Slug+/+ mice (Figure 2A). Consistent with these data, there were manifest increases of extramedullary CFU-S colony numbers in spleen of Slug−/− mice (Figure 2B). In contrast, there was no significant increase in the total numbers of day 16 CFU-S colonies in the BM from Slug−/− mice versus Slug+/+ mice (Figure 2B), which is consistent with HSC frequency in the BM. Together, these data imply that Slug deficiency promotes HSC distribution in the spleen.

CFU-S numbers are elevated in Slug−/− mice. (A) The frequencies of LSK cells as a percentage of total spleen mononuclear cells in Slug+/+ mice, Slug+/− mice, and Slug−/− mice. (B) Numbers of BM-derived and spleen-derived day 16 CFU-S colonies in Slug+/+, Slug+/−, and Slug−/− mice. For CFU assays, BM cells or spleen cells (8 × 104) were injected into lethally irradiated mice. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3 per group). #P > .05, *P < .05, and **P < .01 (Slug−/− or Slug+/− vs Slug+/+).

CFU-S numbers are elevated in Slug−/− mice. (A) The frequencies of LSK cells as a percentage of total spleen mononuclear cells in Slug+/+ mice, Slug+/− mice, and Slug−/− mice. (B) Numbers of BM-derived and spleen-derived day 16 CFU-S colonies in Slug+/+, Slug+/−, and Slug−/− mice. For CFU assays, BM cells or spleen cells (8 × 104) were injected into lethally irradiated mice. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3 per group). #P > .05, *P < .05, and **P < .01 (Slug−/− or Slug+/− vs Slug+/+).

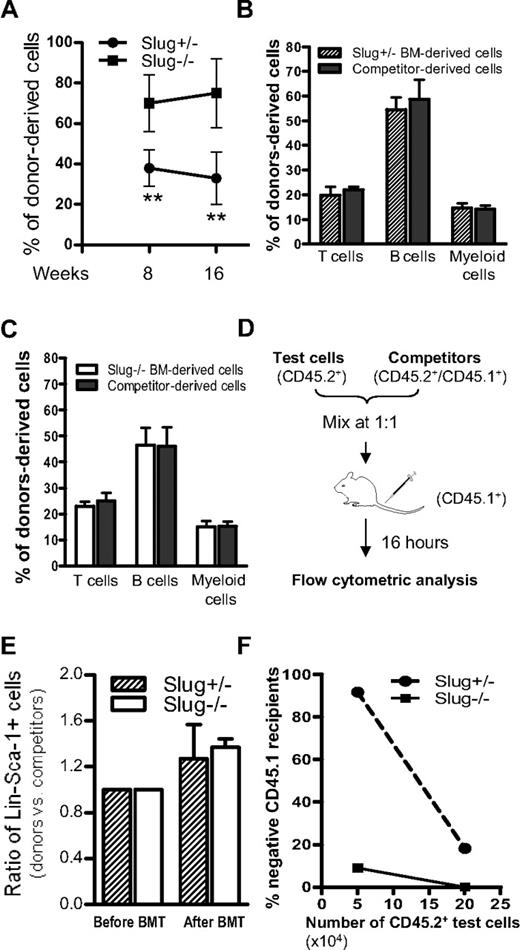

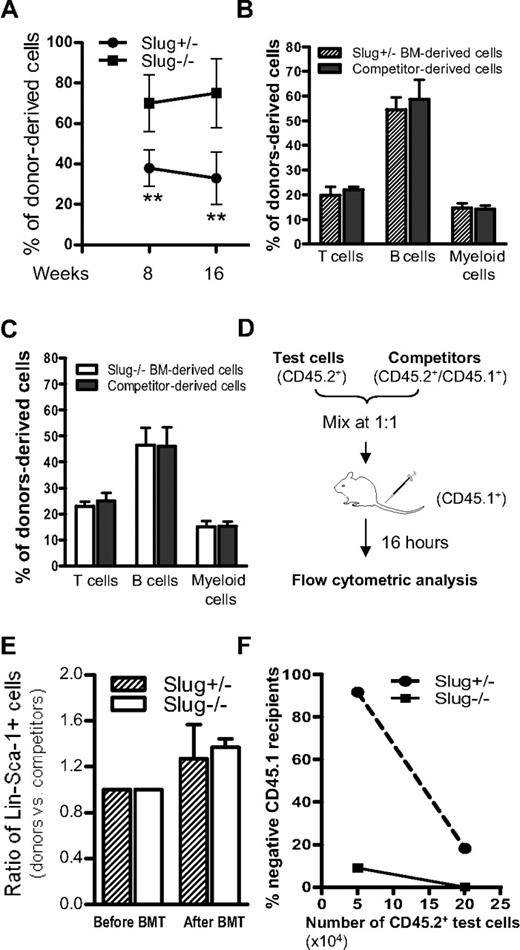

Slug deficiency accelerates repopulating potential of HSCs by increasing their self-renewal ability

Although Slug deficiency does not impair normal differentiation and proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitors under normal conditions (Figure 1), it is conceivable that Slug−/− HSCs have abnormal repopulating potential when these cells home to BM and are forced to repopulate in vivo after BM transplantation. To test this possibility, we transplanted a low dose (2 × 105) of BM cells from Slug−/− or Slug+/− control mice (CD45.2+) together with an equal number of competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) into 2 groups of lethally irradiated recipients, respectively. Competitor BM cells ensured the survival of recipients and served as internal control in this assay. As shown in Figure 3A, the ratio of Slug+/− donor-derived cells (CD45.2+) among total cells derived from injected donor BM cells (CD45.2+ test BM cells and CD45.1+/CD45.2+ competitors) was nearly 40% in Slug+/− donor BM cell-reconstituted mice at 8 weeks and 16 weeks after BM transplantation. In contrast, the ratio of Slug−/− donor BM cell-derived cells was significantly higher in the reconstituted mice of Slug−/− donor BM cells at the indicated time points and increased from 8 weeks (70%) up to 16 weeks (80%) after BM transplantation.

Slug-deficient BM shows enhanced long-term repopulating ability in vivo. (A) Relative repopulating ability of Slug−/− and Slug+/− HSCs in recipients. Equal number (2 × 105) of Slug−/− and Slug+/− BM cells (test cells, CD45.2+) were cotransplanted with wild-type competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/ CD45.2+) into lethally irradiated recipient mice (CD45.1+, n = 8 for each group). The relative repopulating ability of test cells was determined by the percentage of CD45.2+ with total donor-derived cells (CD45.2+ and CD45.1+/ CD45.2+ cells) in blood at 8 weeks and 16 weeks after BM transplantation. There is a significant difference between the 2 groups of reconstituted mice (**P < .01 for Slug−/− vs Slug+/−). (B) Multilineage distribution (4 months after BM transplantation) in Slug+/− BM (test, CD45.2+)–derived and wild-type competitor cell (CD45.1+/ CD45.2+) population-derived hematopoietic cells of recipients (n = 8) transplanted with Slug+/− BM donors. There is no significant difference in the percentage of T, B, and myeloid cells derived from transplanted donor cells from Slug+/− mice and competitive cells. (C) Multilineage distribution (4 months after BM transplantation) in Slug−/− BM (test, CD45.2+) donor-derived and wild-type competitor cell (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) population-derived hematopoietic cells of recipients (n = 8) reconstituted with Slug−/− BM. There is no significant difference in the percentage of T, B, and myeloid cells derived from transplanted donor cells from Slug−/− mice and competitive cells. (D) Diagram of BM homing assay for primitive hematopoietic cells. Test BM cells (CD45.2+) from mice were equally mixed with wild-type competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+), and the ratio of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in test vs competitor cells (the number of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in test BM cells to the number of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in competitor BM cells) was determined by flow cytometry before being injected into lethally irradiated recipients (CD45.1+). Sixteen hours after BM injection, the ratio of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in test vs competitor cells (the percentage of CD45.2+ Lin−Sca-1+ cells to the percentage of CD45.1+/CD45.2+ Lin−Sca-1+ cells) was determined and compared with the ratio of these cells before BM injection. (E) Relative homing ability of Lin−Sca-1+ primitive hematopoietic cells from Slug−/− or Slug+/− mice. The graph indicates that the ratio of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in test (Slug−/− or Slug+/−) BM cells vs competitor cells was comparable in recipients (n = 4). (F) Chimerism in recipients transplanted with BM cells of Slug−/− or Slug+/− mice. Limiting numbers (5 × 104 and 2 × 105) of BM cells from Slug−/− or Slug+/− mice were cotransplanted with 2 × 105 competitor cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) into 2 groups of recipients (n = 8 for each group). Chimerism was analyzed by flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood cells 4 months after BM transplantation. In each animal, 1% or higher of donor-derived (CD45.2+) cells containing T, B, and myeloid cell was defined as positive engraftment. **P < .01 for Slug−/− vs Slug+/−.

Slug-deficient BM shows enhanced long-term repopulating ability in vivo. (A) Relative repopulating ability of Slug−/− and Slug+/− HSCs in recipients. Equal number (2 × 105) of Slug−/− and Slug+/− BM cells (test cells, CD45.2+) were cotransplanted with wild-type competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/ CD45.2+) into lethally irradiated recipient mice (CD45.1+, n = 8 for each group). The relative repopulating ability of test cells was determined by the percentage of CD45.2+ with total donor-derived cells (CD45.2+ and CD45.1+/ CD45.2+ cells) in blood at 8 weeks and 16 weeks after BM transplantation. There is a significant difference between the 2 groups of reconstituted mice (**P < .01 for Slug−/− vs Slug+/−). (B) Multilineage distribution (4 months after BM transplantation) in Slug+/− BM (test, CD45.2+)–derived and wild-type competitor cell (CD45.1+/ CD45.2+) population-derived hematopoietic cells of recipients (n = 8) transplanted with Slug+/− BM donors. There is no significant difference in the percentage of T, B, and myeloid cells derived from transplanted donor cells from Slug+/− mice and competitive cells. (C) Multilineage distribution (4 months after BM transplantation) in Slug−/− BM (test, CD45.2+) donor-derived and wild-type competitor cell (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) population-derived hematopoietic cells of recipients (n = 8) reconstituted with Slug−/− BM. There is no significant difference in the percentage of T, B, and myeloid cells derived from transplanted donor cells from Slug−/− mice and competitive cells. (D) Diagram of BM homing assay for primitive hematopoietic cells. Test BM cells (CD45.2+) from mice were equally mixed with wild-type competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+), and the ratio of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in test vs competitor cells (the number of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in test BM cells to the number of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in competitor BM cells) was determined by flow cytometry before being injected into lethally irradiated recipients (CD45.1+). Sixteen hours after BM injection, the ratio of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in test vs competitor cells (the percentage of CD45.2+ Lin−Sca-1+ cells to the percentage of CD45.1+/CD45.2+ Lin−Sca-1+ cells) was determined and compared with the ratio of these cells before BM injection. (E) Relative homing ability of Lin−Sca-1+ primitive hematopoietic cells from Slug−/− or Slug+/− mice. The graph indicates that the ratio of Lin−Sca-1+ cells in test (Slug−/− or Slug+/−) BM cells vs competitor cells was comparable in recipients (n = 4). (F) Chimerism in recipients transplanted with BM cells of Slug−/− or Slug+/− mice. Limiting numbers (5 × 104 and 2 × 105) of BM cells from Slug−/− or Slug+/− mice were cotransplanted with 2 × 105 competitor cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) into 2 groups of recipients (n = 8 for each group). Chimerism was analyzed by flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood cells 4 months after BM transplantation. In each animal, 1% or higher of donor-derived (CD45.2+) cells containing T, B, and myeloid cell was defined as positive engraftment. **P < .01 for Slug−/− vs Slug+/−.

The repopulating potential of HSCs is determined not only by self-renewal capability of HSCs but also by their differentiation and homing ability.32 Therefore, at 16 weeks after BM transplantation, we analyzed and compared the long-term trilineage differentiation capacity between Slug−/− HSCs and Slug+/− HSCs in these reconstituted mice. In the recipients reconstituted with Slug+/− BM cells, the percentage of T, B, and myeloid cells was similar in Slug+/− donor BM-derived cells and in competitor BM-derived cells (Figure 3B). Similarly, in the recipients of Slug−/− BM donor cells, the Slug−/− HSCs were as potent as the wild-type competitors in their ability to differentiate into trilineages (Figure 3C). Thus, the increased repopulating potential of long-term HSCs in Slug−/− BM was not the result of alteration of differentiation ability.

Next, we asked whether deletion of Slug has an impact on HSC homing ability. We carefully assessed homing ability of Slug−/− HSCs and Slug+/− controls by designing and performing a novel HSC homing assay in which cell sorting and labeling are not required and internal control cells are included (Figure 3D). As shown in Figure 3E, the ratio of the Slug−/− Lin−Sca-1+ cells versus Slug+/− controls was similar before and after BM transplantation, indicating that Slug does not affect HSC homing ability. In summary, Slug deficiency did not affect HSC differentiation and homing ability but accelerated the repopulating potential of HSCs, suggesting that Slug deficiency increases HSC self-renewal.

Deletion of Slug alters CRU frequency

To determine whether Slug deficiency improves HSC self-renewal capability, we performed a limiting dilution competitive repopulation assay to detect HSCs capable of long-term competitive lymphomyeloid repopulation in vivo after BM transplantation. The experimental design, cell doses, numbers of recipients, and numbers of mice positive for trilineages reconstitution are summarized in Table 1. Flow cytometric analysis showed that 9% of the recipients receiving 5 × 104Slug−/− BM cells were negative for trilineage (T, B, and myeloid lineages) reconstitution; in contrast, 92% of the recipients transplanted with 5 × 104Slug+/− BM cells were negative for trilineage (Figure 3F). When the numbers of transplanted BM cells increased up to 2 × 105, all the recipients reconstituted with Slug−/− BM cells were positive for trilineage reconstitution, but 18% of the recipients receiving Slug+/− donors remained negative for trilineage reconstitution (Figure 3F).

The data analysis using limiting analysis software (L-Cals) showed that the frequency of CRU in the BM of Slug−/− and Slug+/− mice was 1 in 20 830 (95% confidence interval, 1 of 45 249 to 1 of 9589) and 1 in 166 810 (95% confidence interval, 1 of 301 315 to 1 of 92 347, respectively). Thus, there were significant differences (P < .001) in total BM CRU content from Slug−/− versus Slug+/− mice (Table 1). These data clearly indicated that Slug deficiency accelerates the HSC repopulating potential in vivo.

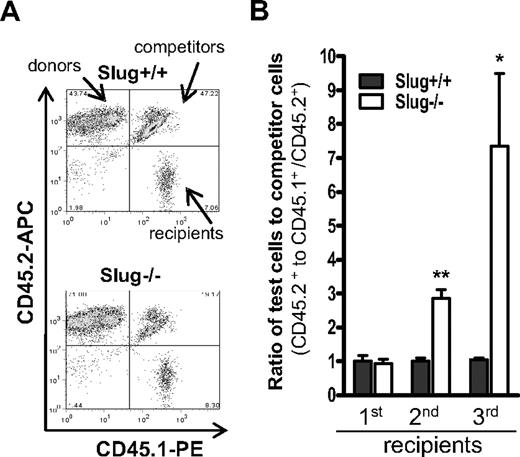

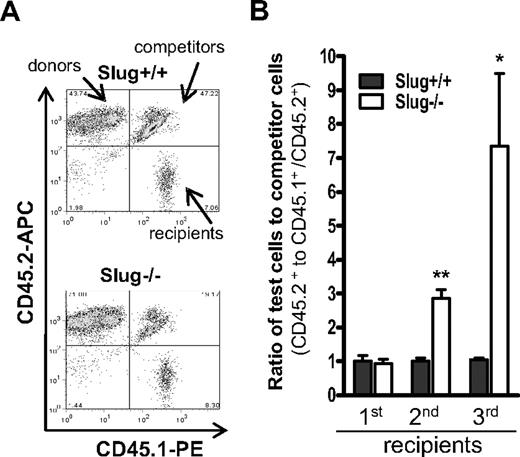

To more rigorously assess effects of Slug on self-renewal activity of HSCs, we performed a serial transplantation assay in which HSCs within BM cells were sequentially transplanted into serial recipients and thus were repeatedly forced to self-renew. We injected 5 × 106 BM cells (CD45.2+) from Slug−/− or Slug+/+ mice together with the same numbers of competitor cells (CD45.1+/ CD45.2+) into 2 groups of lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients. Two months after BM transplantation, flow cytometric analysis (Figure 4A) indicated that the relative ratio of Slug−/− donor or Slug+/+ donor BM cell-derived cells to the competitor cell-derived cells was nearly the same in the primary recipients (Figure 4B). We harvested total BM cells from the 2 groups of primary recipients and injected these cells into 2 separate groups of lethally irradiated secondary recipients. Two months after the second BM transplantation, we analyzed the recipients and found that the relative ratio of Slug−/− donor-derived cells to competitor BM cell-derived cells was 3:1 and that the relative ratio of Slug+/+ donor BM cell-derived cells to competitor BM cell-derived cells was nearly 1:1 (Figure 4B). For the tertiary BM transplantation, we transplanted fresh CD45.1+-recipient mice with total BM MNCs (5 × 106) isolated from the secondary recipients and analyzed them at 2 months after BM transplantation. In the tertiary recipients, the ratio of Slug−/− donor-derived cells to competitor BM cell-derived cells increased up to 7:1; in contrast, the ratio of Slug+/+ donor BM cell-derived cells to competitor BM cell-derived cells remained 1:1 (Figure 4B). Because Slug−/− and Slug+/+ HSCs have the same differentiation and homing ability (Figure 3B-E), these data indicate that deletion of Slug increases HSC self-renewal capability in vivo under the stress of serial BM transplantation.

Serial BM transplantation assay for HSCs within BM of Slug−/− or Slug+/+ mice. (A) A representation of flow cytometric analysis of donor test cell (CD45.2+)– and competitor cell (CD45.1+/CD45.2+)–derived BM cells in the secondary recipients (CD45.1+). (B) Enhanced repopulation capacity of Slug−/− BM MNCs during serial transplantation. BM MNCs from the recipient mice were serially transplanted into recipients as described in “Competitive BM transplantation coupled with serial transfer.” The repopulating capacity of Slug−/− and Slug+/+ BM donor cells was determined in primary (n = 7), secondary (n = 4), and tertiary (n = 3 or 4) recipients at 2 months after BM transplantation. Data shown are the mean ratio ± SD of donor test-derived cells to competitor-derived cells (*P < .05 and **P < .01 for Slug−/− vs Slug+/+).

Serial BM transplantation assay for HSCs within BM of Slug−/− or Slug+/+ mice. (A) A representation of flow cytometric analysis of donor test cell (CD45.2+)– and competitor cell (CD45.1+/CD45.2+)–derived BM cells in the secondary recipients (CD45.1+). (B) Enhanced repopulation capacity of Slug−/− BM MNCs during serial transplantation. BM MNCs from the recipient mice were serially transplanted into recipients as described in “Competitive BM transplantation coupled with serial transfer.” The repopulating capacity of Slug−/− and Slug+/+ BM donor cells was determined in primary (n = 7), secondary (n = 4), and tertiary (n = 3 or 4) recipients at 2 months after BM transplantation. Data shown are the mean ratio ± SD of donor test-derived cells to competitor-derived cells (*P < .05 and **P < .01 for Slug−/− vs Slug+/+).

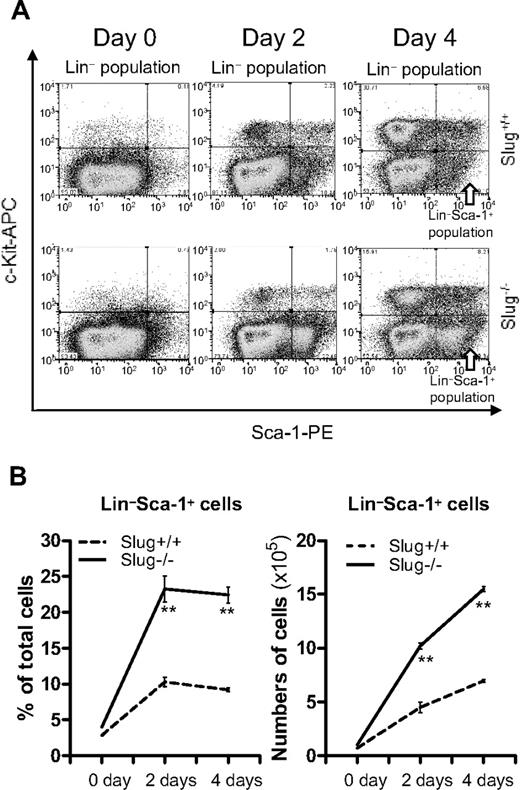

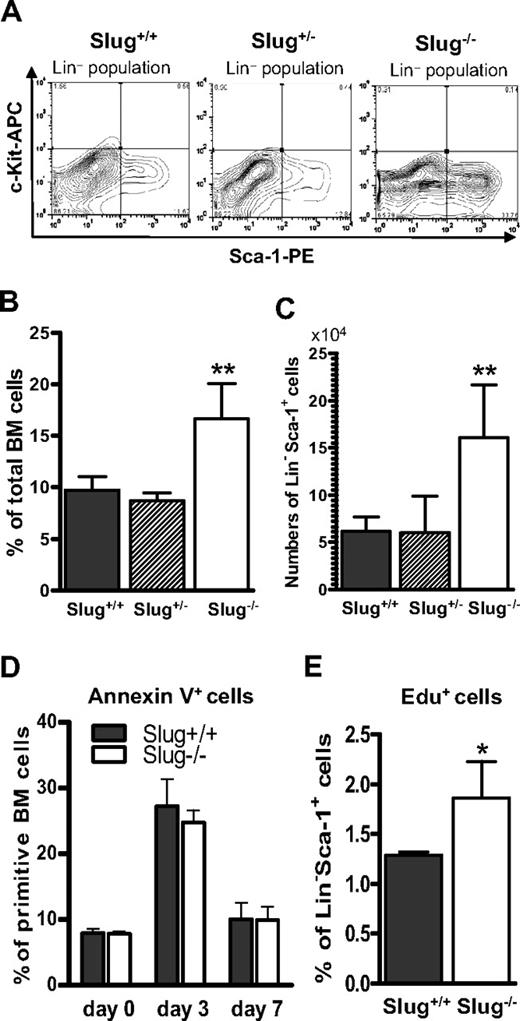

Deletion of Slug promotes HSC proliferation in vivo after 5-FU treatment

To further test the notion that Slug deficiency leads to an improvement in the stress response of hematopoietic cells, we treated mice with 5-FU, which is toxic to cycling cells and accelerates the entry of HSCs into the cell cycle. According to previous studies,33,34 a single dose of 5-FU injection purges cycling hematopoietic cells, including progenitors and HSCs, and spares primitive HSCs because of their slow cycling. Spared primitive HSCs then become activated and expand through symmetric division. 5-FU treatment transiently alters HSC phenotype from Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit + to Lin−Sca-1+.34,35 From the limiting dilution competitive repopulation assay (Table 1) and the serial transplantation assay (Figure 4), we found that Slug−/− HSCs have elevated self-renewal capacity and thus should repopulate faster after 5-FU treatment than Slug+/+ and Slug+/− control mice. To test this possibility, we injected Slug−/−, Slug+/−, and wild-type littermates with a single dose of 5-FU. Seven days after 5-FU treatment, flow cytometric analysis indicated that the percentage of Lin−Sca-1+ cells was 2-fold higher in Slug−/− mice than in Slug+/− and Slug+/+ control mice (Figure 5A-B). Consistently, there were 2.5-fold increases in the numbers of HSCs in Slug−/− mice than in Slug+/− and Slug+/+ control mice (Figure 5C).

Increased expansion of HSCs in Slug−/− mice after 5-FU treatment. (A) A representation of flow cytometric analysis of Lin−Sca-1+ HSCs in Slug+/+, Slug+/−, and Slug−/− BM 7 days after a single injection of 5-FU (300 mg/kg body weight). (B) The ratio of remaining Lin−Sca-1+ cells at 7 days after 5-FU treatment in 3 groups of mice (Slug+/+ mice, n = 5; Slug+/− mice, n = 4; Slug−/−, n = 5). (C) Total numbers of surviving Lin−Sca-1+ cells 7 days after 5-FU treatment in Slug+/+ (n = 5), Slug+/− (n = 4), and Slug−/− (n = 5) mice. (D) Analysis of apoptotic rate in primitive hematopoietic cell population in BM using an annexin V–based apoptosis assay. BM cells were harvested from Slug−/− and Slug+/+ mice at 0, 3, and 7 days after 5-FU treatment. Primitive hematopoietic cells were gated as Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (for 0 day) or Lin−Sca-1+ (for 3 and 7 days after 5-FU treatment), and the apoptotic cells were identified by a fluorescence-labeled annexin V. Apoptotic primitive hematopoietic cells (annexin V+ Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ or annexin V+ Lin−Sca-1+) were analyzed by flow cytometry and represent a percentage. There is no significant difference in the percentage of annexin V+ Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ cells (0 day) and annexin V+ Lin−Sca-1+ cells (3 and 7 days after 5-FU treatment) from Slug+/+ and Slug−/− mice. The data shown are the mean of the triplicate. (E) Analysis of Lin−Sca-1+ cell population in S phase. Total BM cells were harvested from Slug+/+ and Slug−/− mice at 5 days after 5-FU treatment and then assayed for Edu incorporation (n = 3). The ratio of Edu+ cell in Lin−Sca-1+ cell population was determined by flow cytometry. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05 and **P < .01 for Slug−/− vs Slug+/+.

Increased expansion of HSCs in Slug−/− mice after 5-FU treatment. (A) A representation of flow cytometric analysis of Lin−Sca-1+ HSCs in Slug+/+, Slug+/−, and Slug−/− BM 7 days after a single injection of 5-FU (300 mg/kg body weight). (B) The ratio of remaining Lin−Sca-1+ cells at 7 days after 5-FU treatment in 3 groups of mice (Slug+/+ mice, n = 5; Slug+/− mice, n = 4; Slug−/−, n = 5). (C) Total numbers of surviving Lin−Sca-1+ cells 7 days after 5-FU treatment in Slug+/+ (n = 5), Slug+/− (n = 4), and Slug−/− (n = 5) mice. (D) Analysis of apoptotic rate in primitive hematopoietic cell population in BM using an annexin V–based apoptosis assay. BM cells were harvested from Slug−/− and Slug+/+ mice at 0, 3, and 7 days after 5-FU treatment. Primitive hematopoietic cells were gated as Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (for 0 day) or Lin−Sca-1+ (for 3 and 7 days after 5-FU treatment), and the apoptotic cells were identified by a fluorescence-labeled annexin V. Apoptotic primitive hematopoietic cells (annexin V+ Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ or annexin V+ Lin−Sca-1+) were analyzed by flow cytometry and represent a percentage. There is no significant difference in the percentage of annexin V+ Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ cells (0 day) and annexin V+ Lin−Sca-1+ cells (3 and 7 days after 5-FU treatment) from Slug+/+ and Slug−/− mice. The data shown are the mean of the triplicate. (E) Analysis of Lin−Sca-1+ cell population in S phase. Total BM cells were harvested from Slug+/+ and Slug−/− mice at 5 days after 5-FU treatment and then assayed for Edu incorporation (n = 3). The ratio of Edu+ cell in Lin−Sca-1+ cell population was determined by flow cytometry. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < .05 and **P < .01 for Slug−/− vs Slug+/+.

Slug was implicated in the regulation of apoptosis and cell cycle.36,37 Thus, we hypothesized that deletion of Slug alters HSC survival or increases cell-cycle progression of HSCs after treatment with 5-FU or both. To assess these possibilities, we first analyzed the ratio of apoptotic cells within Lin−Sca-1+ cell population by an annexin V–based apoptosis assay. Our data showed that the percentage of apoptotic cells within primitive hematopoietic cell population was comparable in Slug+/+ and in Slug−/− mice before and at 3 and 7 days after 5-FU treatment (Figure 5D). According to the reports published by Venezia et al34 and Randall and Weissman,35 c-Kit expression was decreased by 10-fold after 5-FU treatment and HSCs isolated from 5-FU–treated mice could be identified by Lin−Sca-1+ phenotype. As described in “Cell-cycle analysis by the Edu incorporation assay,” we performed Edu incorporation assay on Lin−Sca-1+ cell population isolated from Slug+/+ and Slug−/− mice. Figure 5E shows that the percentage of Edu+ cells (S phase cells) among Lin−Sca-1+ cell populations was significantly higher in Slug−/− mice than in Slug+/+ mice. Together, these data suggest that Slug deficiency promotes 5-FU–activated HSC expansion largely by increasing their proliferation, but not cell survival.

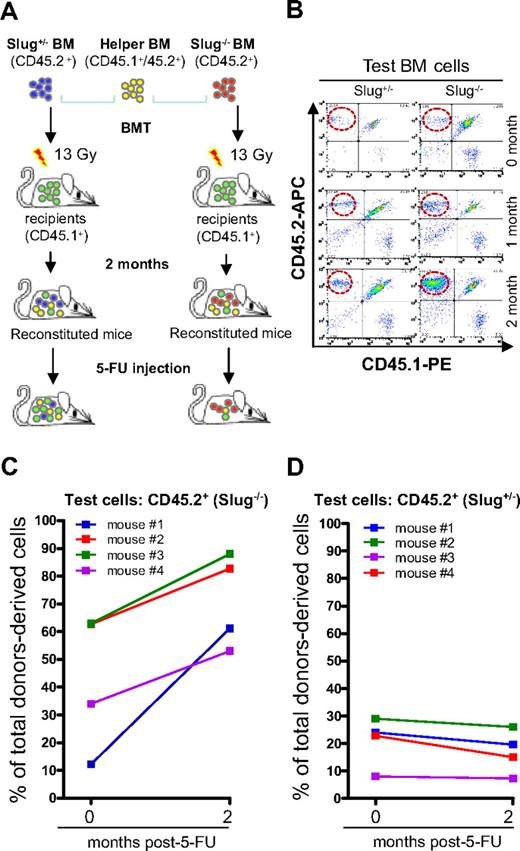

Slug deficiency enhances the repopulating potential of HSCs activated by 5-FU

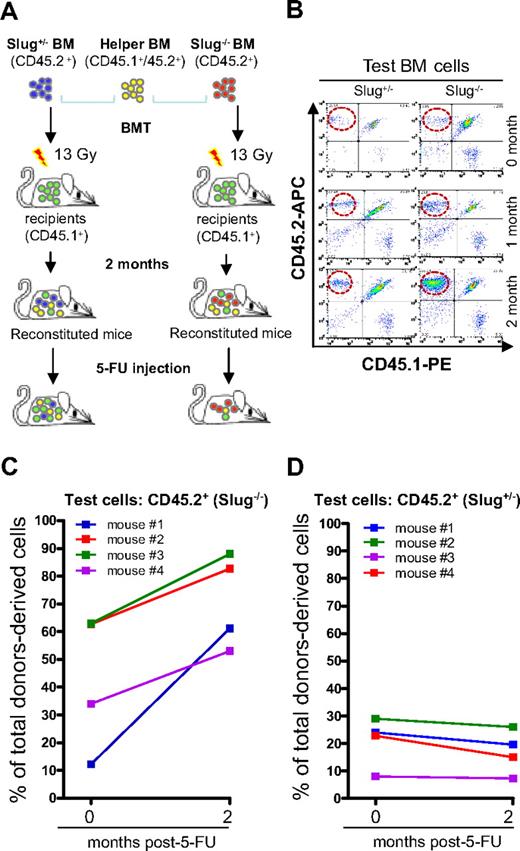

HSC self-renewal relies on proliferation, and excessive proliferation could impair HSC self-renewal capability.38-40 Our data indicated that deletion of Slug enhanced HSC expansion in vivo after the stress of 5-FU treatment. Thus, we decided to assess whether deletion of Slug impairs the repopulating potential of HSCs activated by 5-FU treatment by an in vivo HSC repopulating assay based on the myelosuppressive model of treatment with 5-FU.33,34 It was established that, on 5-FU treatment, quiescent long-term HSCs become activated and then expand themselves by symmetric division and consequently differentiate into trilineages, thus repopulating whole hematopoietic compartment. We generated the reconstituted mice (CD45.1+) with various numbers of competitor cells (CD45.1+5.2+) and donor test cells from Slug−/− BM or Slug+/− BM (CD45.2+), as shown in Figure 6A. Two months after reconstitution, we analyzed the ratio of test and competitor cell-derived hematopoietic cells in these animals and then injected them with a single dose of 5-FU (Figure 6A). After 5-FU treatment, we measured by flow cytometric analysis (Figure 6B), the percentage of test cell-derived cells (CD45.2+), and competitor-derived cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) among total BM cells derived from these 2 different donors. Figure 6C illustrates the percentage of Slug−/− test cell-derived cells (CD45.2+) increased in recipients transplanted with Slug−/− BM cells at 4 months after 5-FU treatment. In contrast, in Slug+/− BM cell-reconstituted mice, the percentage of Slug+/− test cell-derived (CD45.2+) remained very similar or even slightly decreased at 4 months after 5-FU treatment (Figure 6D). The recipients in these 2 groups of mice have the same BM microenvironments; thus, deletion of Slug increased the repopulating potential of 5-FU-activated HSCs in a cell-autonomous manner.

Enhanced repopulating capacity of Slug−/− HSCs in reconstituted mice after 5-FU administration. (A) Diagram of in vivo HSC repopulating assay. Donor BM cells from Slug+/− or Slug−/− mice (CD45.2+) were injected together with competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) into recipient mice that received a prior 13-Gy irradiation. A single dose of 5-FU (300 mg/kg body weight) was injected into these reconstituted mice at 2 months after BM transplantation. Ratio of donor- and competitor-derived cells in peripheral blood was determined before and after 5-FU treatment by flow cytometric analysis. (B) A representative flow cytometric analysis of test donor-derived hematopoietic cells before and after 5-FU injection (1 and 2 months). (C-D) Enhanced repopulating potential of Slug−/− HSCs in vivo after 5-FU treatment. The percentage of Slug−/− test donor-derived cells (CD45.2+) within the total donor-derived cell population (CD45.2+ cells and CD45.1+/CD45.2+ cells) increased in Slug−/− BM-reconstituted mice (n = 4) at 4 months after 5-FU treatment (C). In contrast, the ratio of Slug+/− test donor-derived cells did not significantly change in Slug+/− BM-reconstituted recipients (n = 4) after 5-FU treatment (D).

Enhanced repopulating capacity of Slug−/− HSCs in reconstituted mice after 5-FU administration. (A) Diagram of in vivo HSC repopulating assay. Donor BM cells from Slug+/− or Slug−/− mice (CD45.2+) were injected together with competitor BM cells (CD45.1+/CD45.2+) into recipient mice that received a prior 13-Gy irradiation. A single dose of 5-FU (300 mg/kg body weight) was injected into these reconstituted mice at 2 months after BM transplantation. Ratio of donor- and competitor-derived cells in peripheral blood was determined before and after 5-FU treatment by flow cytometric analysis. (B) A representative flow cytometric analysis of test donor-derived hematopoietic cells before and after 5-FU injection (1 and 2 months). (C-D) Enhanced repopulating potential of Slug−/− HSCs in vivo after 5-FU treatment. The percentage of Slug−/− test donor-derived cells (CD45.2+) within the total donor-derived cell population (CD45.2+ cells and CD45.1+/CD45.2+ cells) increased in Slug−/− BM-reconstituted mice (n = 4) at 4 months after 5-FU treatment (C). In contrast, the ratio of Slug+/− test donor-derived cells did not significantly change in Slug+/− BM-reconstituted recipients (n = 4) after 5-FU treatment (D).

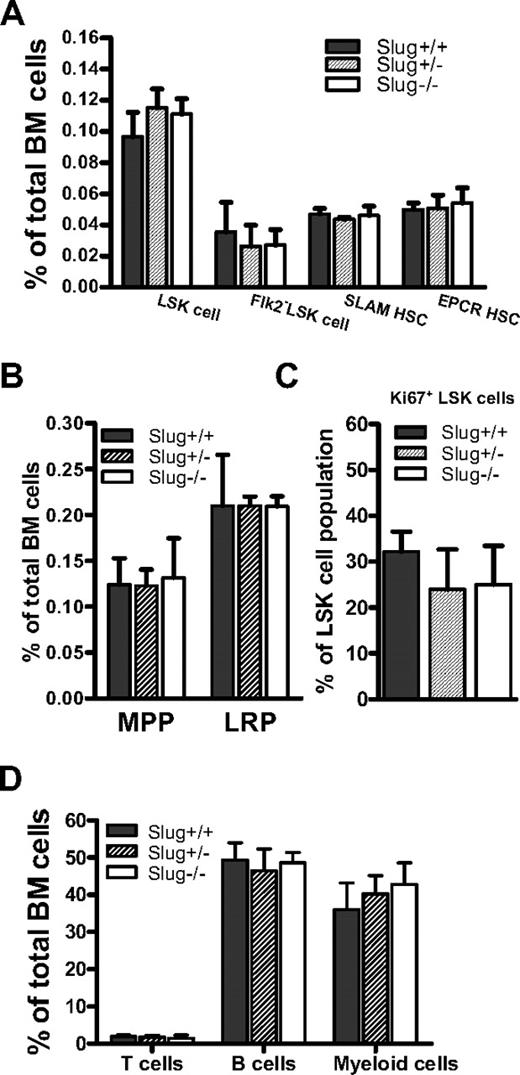

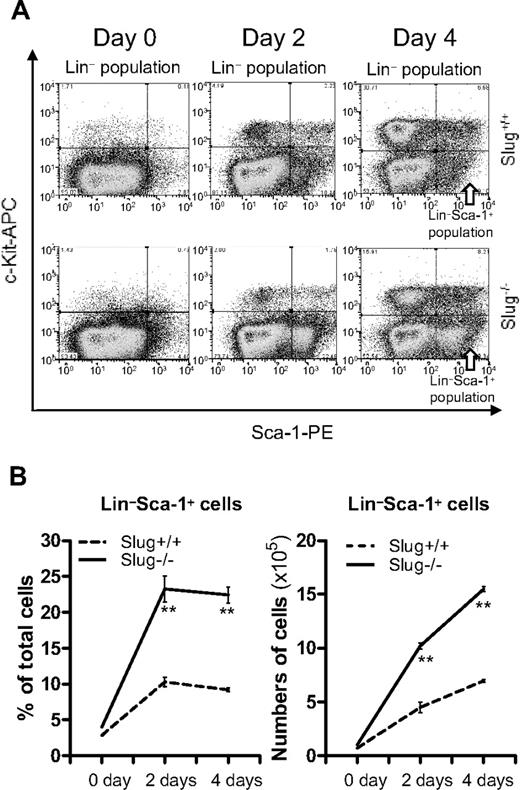

Deletion of Slug accelerates the expansion of HSCs activated by 5-FU in vitro

According to our findings (Figure 5A-B), it is apparent that Slug negatively regulates HSC self-renewal division when activated by 5-FU treatment. Therefore, it was tempting for us to test whether deletion of Slug increases HSC expansion in vitro, using the TPO and SCF supplemented culture system that supports short-term in vitro expansion of functional HSCs.41 To this end, we isolated HSC-enriched BM cells from Slug−/− and Slug+/+ control mice (all in Bcl-2 transgenic background) at day 5 after 5-FU treatment and cultured them in the serum-free medium supplemented with TPO and SCF (1 ng/mL). It was previously shown that HSCs from Bcl-2 transgenic mice can be propagated in a serum-free medium in very low concentrations of SCF, without any other cytokines.42 Flow cytometric analysis (Figure 7A) indicated that the percentage of HSCs (Lin−Sca-1+) cells at day 2 and 4 after in vitro culture was 2 times higher in BM cells from 5-FU-treated Slug−/− mice, in contrast to the 5-FU-treated Slug+/+ mice (Figure 7B left panel). In agreement with this result, there were 3 times more Slug−/− Lin−Sca-1+ cells than Slug+/+ Lin−Sca-1+ cells at 4 days after in vitro culture (Figure 7B right panel). Together, these data indicated that deletion of Slug accelerated HSC expansion in vitro, suggesting a negatively regulative role of Slug in the regulation of HSC self-renewal division.

Accelerated in vitro expansion of Lin−Sca-1+ cells from Slug−/− mice. (A) A representation of flow cytometric analysis of Lin−Sca-1+ cells during cell culture in vitro. Total BM cells were prepared from Slug+/+ and Slug−/− mice that carried the Bcl-2 transgene at 5 days after 5-FU treatment, and then were cultured in the SFEM medium containing SCF and TPO (1 ng/mL). Lin−Sca-1+ cells were identified by flow cytometric analysis during cell culture. (B) The ratio (left panel) and total number (right panel) of Lin−Sca-1+ cells before and at 2 and 4 days of in vitro cell culture. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. **P < .01 for Slug+/+ vs Slug−/−.

Accelerated in vitro expansion of Lin−Sca-1+ cells from Slug−/− mice. (A) A representation of flow cytometric analysis of Lin−Sca-1+ cells during cell culture in vitro. Total BM cells were prepared from Slug+/+ and Slug−/− mice that carried the Bcl-2 transgene at 5 days after 5-FU treatment, and then were cultured in the SFEM medium containing SCF and TPO (1 ng/mL). Lin−Sca-1+ cells were identified by flow cytometric analysis during cell culture. (B) The ratio (left panel) and total number (right panel) of Lin−Sca-1+ cells before and at 2 and 4 days of in vitro cell culture. All data are expressed as mean ± SD. **P < .01 for Slug+/+ vs Slug−/−.

Discussion

Consistent with the previous studies,13,43 we found that hematopoiesis in Slug−/− mice is normal in the BM,. Flow cytometric analysis indicated that there were comparable numbers of primitive hematopoietic cells in Slug−/− mice, Slug+/+, or Slug+/− littermate controls. Together, these data suggested that, while being expressed in HSCs and hematopoietic progenitor cells, Slug was not required for normal hematopoiesis and maintenance of the HSC pool in BM. In contrast, CFU-S assays detected the alterations of frequencies of primitive hematopoietic cells in the spleens but not in the BM of Slug−/− mice. These data suggested that Slug may differentially regulate primitive cell growth or distribution in the BM and spleens. Similarly, an elevated number of CFU-S in spleens was documented in SHIP−/− mice.44 Although mechanisms for differential regulation of primitive cell growth remain to be investigated, we know that primitive cells in both of BM and spleens differentially respond to the steel factor, which greatly increases splenic HSC activity but slightly reduces BM HSC activity.45 Interestingly, Slug expression could be up-regulated by steel factor treatment in the BaF3 cell line. Therefore, in the future, it will be tempting to study whether Slug functions as a negative regulator in the c-kit–mediated signaling pathway in HSCs.

Slug−/− HSCs could repopulate hematopoiesis when transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients in large excess.14 However, the limiting-dilution competitive repopulation assay revealed significant differences (P < .001) in the CRU frequencies of HSCs between Slug−/− BM cells and Slug+/− controls. This result was further supported by a serial BM transplantation assay, the most rigorous test for HSC potential.32 In this assay, Slug−/− HSCs indeed exhibited 3-fold and 7-fold repopulating capability in the secondary and tertiary recipients, respectively, compared with Slug+/+ HSCs. In addition, we also demonstrated that HSC differentiation and homing ability were not altered when Slug was deleted in hematopoietic cells. Thus, these data suggest that deletion of Slug enhances HSC repopulating potential largely by increasing HSC self-renewal capability.

HSCs are originally considered to be quiescent within the BM and resistant to 5-FU. The primitive 5-FU-activated HSCs can enter the cell cycle and expand themselves by symmetric division. Our results demonstrate that deletion of Slug increased both the percentage and total numbers of Lin−Sca-1+ HSCs in Slug−/− mice. Corroborating this result, we found that the percentage of HSCs (Lin−Sca-1+) in S-phase was higher in Slug−/− mice than Slug+/+ mice after 5-FU treatment.

Still, the underlying molecular mechanisms for Slug's role in regulation of cell cycle in HSCs remain to be studied in the future. It was reported that overexpression of Snail1, another member of Snail/Slug transcription family, could regulate expression of cell-cycle regulators, such as cyclin D2 and p21 in cell lines other than hematopoietic cells.46 Therefore, it will be interesting to see whether these 2 cell-cycle regulators and other regulators are deregulated in Lin−Sca-1+ HSCs from Slug−/− mice after 5-FU treatment.

A tight regulation of cell-cycle progress is essential for the self-renewal and long-term repopulating ability of HSCs. Hampering HSC proliferation could lead to a decreased repopulating potential.47,48 Conversely, hastening HSC proliferation does not routinely result in a subsequent expansion of self-renewing HSCs but could result in exhaustion of HSCs39 and severely decrease long-term engraftment ability.49,50 The in vivo competitive repopulating assay showed that Slug−/− HSCs not only proliferate faster but also have enhanced long-term repopulating ability in 5-FU–treated animals. Therefore, in vivo properties of Slug and p21 in the regulation of HSC repopulating potential are very different, although both of them negatively regulate HSC proliferation.

When cultured in vitro with SCF and TPO cytokines, HSCs can proliferate by symmetric and asymmetric division and subsequently differentiate into different lineages.41 Consistent with Slug's role as a negative regulator of HSC proliferation in vivo, Slug−/− HSCs from 5-FU–treated mice showed higher proliferation rate when cultured with SCF and TPO in vitro. Clearly, further extensive studies are needed to dissect the molecular mechanisms by which Slug regulates the self-renewal of HSCs.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues at Maine Medical Center Research Institute for their critical review and the Cell Separation and Analysis Core at Maine Medical Center Research Institute for the cell analysis and sorting.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources (grant P20 RR018789). W.-S.W. was supported by a K01 award from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K01DK078180).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: Y.S. designed and performed research and analyzed data; L.S. and H.B. performed research; Z.Z.W. contributed to research design; and W.-S.W. designed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Wen-Shu Wu, Maine Medical Center Research Institute, 81 Research Dr, Scarborough, ME 04074; e-mail: wuw@mmc.org.