Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) persists in the immune host by preferentially colonizing the isotype-switched (IgD−CD27+) memory B-cell pool. In one scenario, this is achieved through virus infection of naive (IgD+CD27−) B cells and their differentiation into memory via germinal center (GC) transit; in another, EBV avoids GC transit and infects memory B cells directly. We report 2 findings consistent with this latter view. First, we examined circulating non–isotype-switched (IgD+CD27+) memory cells, a population that much evidence suggests is GC-independent in origin. Whereas isotype-switched memory had the highest viral loads by quantitative polymerase chain reaction, EBV was detectable in the nonswitched memory pool both in infectious mononucleosis (IM) patients undergoing primary infection and in most long-term virus carriers. Second, we examined colonization by EBV of B-cell subsets sorted from a unique collection of IM tonsillar cell suspensions. Here viral loads were concentrated in B cells with the CD38 marker of GC origin but lacking other GC markers CD10 and CD77. These findings, supported by histologic evidence, suggest that EBV infection in IM tonsils involves extrafollicular B cells expressing CD38 as an activation antigen and not as a marker of ectopic GC activity.

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), an orally transmitted γ-1 herpesvirus, establishes lytic infection in the oropharynx while spreading as a latent infection into the B-lymphoid system.1 This latter process is poorly understood, but in tonsil sections from infectious mononucleosis (IM) patients undergoing primary infection, large numbers of B lymphoblasts are detectable expressing the Epstein-Barr– encoded RNAs (EBERs) accompanied, in some cells, by the virus-coded nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) and latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1).2-4 Coincidence of these markers indicates a growth-transforming infection like that seen in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines in vitro, where the full spectrum of latent cycle genes (EBERs, BamHI A-encoded RNAs, EBNAs 1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, and -LP, and LMPs 1 and 2) are expressed.1 In vivo, however, at least some of these growth-transformed cells then appear to down-regulate viral antigen expression, producing a reservoir of EBER-positive antigen-negative B cells, now largely in a resting state,5,6 that persist within blood and oropharyngeal lymphoid tissues.7

The human circulating B-cell pool contains 3 main populations8 : (1) antigen-inexperienced, naive (IgD+CD27−) cells with germ line Ig sequences, (2) isotype-switched (IgD−CD27+) memory cells, with mutated Ig sequences, that have been selected from antigen-driven germinal center (GC) reactions where clonal B-cell expansion is accompanied by Ig gene hypermutation and Ig class switching, and (3) nonswitched (IgD+CD27+) memory cells whose origins are obscure; these cells also carry mutated Ig sequences, but their presence in immunodeficient patients lacking both GC structures and isotype-switched memory suggests that they may arise independently of antigen stimulation/GC transit.9-12 Importantly, when B cells in the blood of healthy virus carriers or IM patients were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) on the basis of either IgD or CD27 status, EBV-infected cells were found to be sequestered in the IgD− and in the CD27+ fractions,13-15 consistent with selective colonization of the isotype-switched (IgD−CD27+) memory pool.

Because naive and memory cells appear equally infectable in vitro,16 how the virus achieves such selectivity in vivo remains a key question. One hypothesis is based largely on studies of tonsillar B-cell subsets in long-term virus carriers. There EBV again preferentially colonized isotype-switched memory; however, in tonsils with evidence of ongoing virus replication (and therefore mature virions and new infection events), the virus was also detected in naive B cells.17,18 Extrapolating from these findings to primary infection, it was proposed that incoming virions first target naive B cells as a growth-transforming infection that, mimicking antigen stimulation, drives these cells down the physiologic, GC-dependent route into memory. Furthermore, by restricting antigen expression to certain key viral proteins during GC transit, infected cells could both retain the viral genome during centroblast proliferation and then, as centrocytes, promote their own selection into memory.19

A different hypothesis, envisaging a GC-independent route into memory, is based largely on evidence from IM tonsil sections.20 There EBV-infected cells localize to extrafollicular areas rather than GCs2-4 and are dominated by clones with stable memory Ig genotypes without ongoing hypermutation4 ; even rare EBER-positive cells within GCs had memory genotypes distinct from the surrounding GC reaction.21 This implied either that preexisting memory B cells are preferentially infected or that the virus infects both cell types but infected memory cells have a survival advantage.20 However, the disruption of tissue architecture in IM tonsillar tissues can make histologic findings difficult to interpret and, even though outside GCs, EBV-infected cells may display features of a GC-like reaction ectopically. Crucially, IM tonsillar B cells have never been sorted into phenotypically distinct subsets in the way used to analyze EBV infection in carrier tonsils.

Here we address 2 of these issues. First, we ask whether the putatively GC-independent, nonswitched memory B-cell subset is colonized by EBV during primary or persistent infection. Second, we examine the distribution of EBV within B-cell subsets sorted from IM tonsils and ask whether infected cells display the GC phenotype.

Methods

Donors and samples

Buffy coats came from healthy adult virus carriers (National Blood Service, Birmingham, United Kingdom) and 60-mL blood samples from acute IM patients.22 Fresh tonsils came from virus carriers undergoing routine tonsillectomy and from acute IM patients undergoing emergency tonsillectomy to relieve airway obstruction.22 All samples were collected after written informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and studies were approved by the Ethics Committees of South Birmingham Health Authority and the Faculty of Clinical Medicine Mannheim, Ruprecht-Karls University of Heidelberg (Heidelberg, Germany). Formalin-fixed acute IM tonsils from the archives of the Pathological Institute, University Hospital Erlangen (Erlangen, Germany) were used according to local Ethics Committee guidelines.

Isolation of blood B-cell subsets

B cells were positively selected from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using M-450 CD19 (Pan B) Dynabeads (Dynal Biotech, Lake Success, NY) followed by bead detachment, and enumerated by staining an aliquot with phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD20 (1:40, Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA) monoclonal antibody (mAb). Remaining B cells were costained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-IgD (1:40, Dako North America) and PE-conjugated anti-CD27 (1:20, BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA) antibodies (Abs), and IgD+CD27− naive, IgD+CD27+ nonswitched memory and IgD−CD27+ isotype-switched memory B-cell subsets simultaneously collected by FACS sorting using a Mo-Flo sorter (Dako North America); small aliquots were reanalyzed to assess purity.

Isolation of tonsillar B-cell subsets

Tonsillar mononuclear cells, used immediately or after cryostorage as described,22 were first depleted of T cells using M-450 CD3 (Pan T) Dynabeads (Dynal Biotech), and B cells enumerated as described in “Isolation of blood B-cell subsets.” In some experiments, B cells were costained with PE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD38 (1:40; BD Biosciences PharMingen), FITC-conjugated anti-IgD (1:40, Dako North America), and PE-conjugated anti-CD27 (1:20; BD Biosciences PharMingen) Abs to identify 5 distinct subsets: CD38hi plasma cells, CD38+ GC cells and, from the CD38− fraction, IgD+CD27− (naive), IgD+CD27+ (nonswitched memory), and IgD−CD27+ (switched memory) cells.23 In other experiments, B cells were costained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD77 (1:20; BD Biosciences PharMingen), PE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD10 (1:20; BD Biosciences PharMingen), and PE-conjugated anti-IgD (1:20; Dako North America) Abs, to identify 4 distinct subsets: CD77+ centroblasts, CD77−CD10+ centrocytes, and 2 populations of non-GC cells (CD77−CD10−), either IgD+ or IgD−.23 With both staining protocols, B-cell subsets were sorted and assessed for purity as described in “Isolation of blood B-cell subsets.”

EBV genome load, virus-infected cell frequencies, and viral gene expression

EBV genome loads were assayed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a primer-probe combination specific for BALF5 (EBV DNA polymerase) and normalized against the amount of amplified cellular β2-microglobulin DNA as described previously.24 Values shown are the mean of triplicate samples (600 ng DNA from PBMCs/total B cells/naive B cells or 50 ng DNA from memory B-cell subsets); SDs were less than 20%. Values less than 10 copies per 106 cells are reported as negative.

The frequency of EBV-infected cells in each B-cell population was estimated by limiting dilution analysis.13 Sorted cell populations were serially diluted 2-fold (6-8 dilutions), and then 8 replicates of each dilution were added to a 96-well PCR plate. After centrifugation at 1500g for 15 minutes, cell pellets were resuspended in 10 μL lysis solution (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Tween-20, 0.4 mg/mL Proteinase K) and incubated at 55°C for 2 hours. Proteinase K was then inactivated (95°C for 15 minutes) and the samples screened for the presence of EBV DNA by real-time PCR in a final volume of 50 μL. The frequency of virus genome-positive cells was estimated from a nonlinear regression analysis of input cell number against log fraction-negative samples for each dilution tested based on a Poisson distribution.13

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

Statistical analysis

Viral load data and B-cell subset distribution data were plotted and statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Peripheral blood B-cell subsets in primary and persistent infection

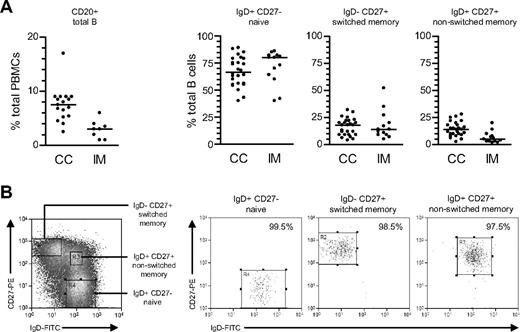

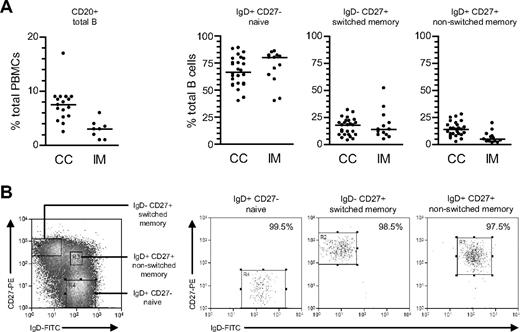

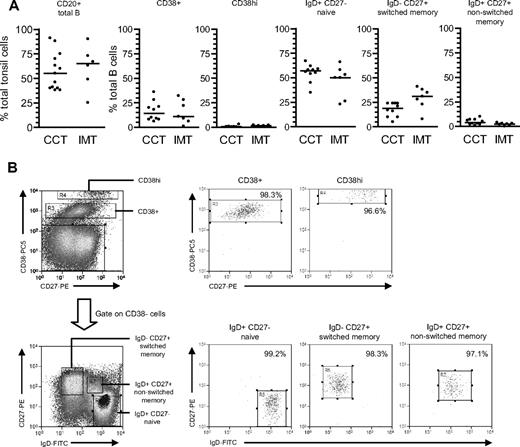

From CD20 staining (Figure 1A), the proportion of total B cells within PBMCs was lower in acute IM patients than in chronic carriers; note that this is a consequence of CD8+ T-cell expansion in IM blood22 rather than a true reduction in circulating B-cell numbers.29 Thereafter total B cells, positively selected from such PBMC preparations, were double-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-IgD and PE-conjugated anti-CD27 Abs to identify naive (IgD+CD27−), isotype-switched memory (IgD−CD27+), and nonswitched memory (IgD+CD27+) subsets. Broadly similar subset distributions were seen in the 2 types of donor, although tending toward lower proportions of nonswitched memory cells in IM.

Characterization and isolation of peripheral blood B-cell subsets. (A) Total PBMCs were stained with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD20 mAb to enumerate the percentage of B cells (●) in blood from chronic virus carriers (CC) and IM patients. Purified B cells were subsequently double-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-IgD and PE-conjugated anti-CD27 Abs to enumerate the percentages of IgD+CD27− naive, IgD−CD27+ isotype-switched memory and IgD+CD27+ nonswitched memory B cells. Median values for each group are shown by the horizontal bars; from P values, the only significant difference was for total percentage B cells in CC versus IM blood (P < .001). (B) Purified B cells double-stained as in panel A to identify naive, switched memory and nonswitched memory subsets were separated using the indicated sort gates and the isolated B-cell populations subsequently reanalyzed to determine the sort purities. Shown are representative data from donor CC17.

Characterization and isolation of peripheral blood B-cell subsets. (A) Total PBMCs were stained with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD20 mAb to enumerate the percentage of B cells (●) in blood from chronic virus carriers (CC) and IM patients. Purified B cells were subsequently double-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-IgD and PE-conjugated anti-CD27 Abs to enumerate the percentages of IgD+CD27− naive, IgD−CD27+ isotype-switched memory and IgD+CD27+ nonswitched memory B cells. Median values for each group are shown by the horizontal bars; from P values, the only significant difference was for total percentage B cells in CC versus IM blood (P < .001). (B) Purified B cells double-stained as in panel A to identify naive, switched memory and nonswitched memory subsets were separated using the indicated sort gates and the isolated B-cell populations subsequently reanalyzed to determine the sort purities. Shown are representative data from donor CC17.

Viral loads in peripheral blood B cells and B-cell subsets

The aforementioned B-cell subsets were then isolated by FACS sorting. Figure 1B illustrates typical sort gates used and the sort purities obtained. Naive B cells were routinely isolated to purities of more than 99%, switch memory B cells to more than 98% and nonswitch memory B cells to more than 97%, with contaminants in the latter population mainly coming from the IgD+CD27− naive B-cell quadrant. DNA was extracted from an aliquot of unfractionated B cells and from the sorted populations, and EBV genome loads assayed by quantitative PCR using a cellular gene, β2-microglobulin, as an internal control. As shown in Figure S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), viral loads in unfractionated B cells (expressed as virus genome copies per 106 cells) were generally approximately 2 log greater in IM patients than in chronic carriers, although absolute values ranged widely within each group.

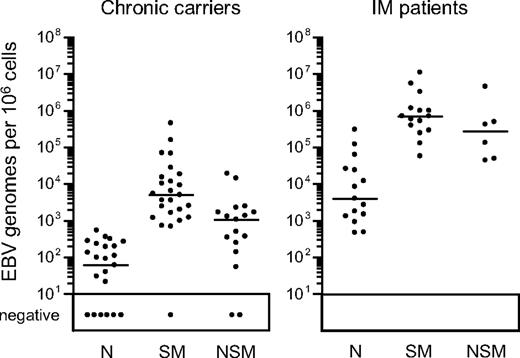

Figure 2 presents a summary of viral loads found in the 3 isolated B-cell subsets from both chronic carriers and IM patients; detailed results from individual donors in each group are given in Table 1. In accord with the literature,14 in chronic carriers, the virus load per 106 cells was typically much higher (median, 82-fold) in the isotype-switched memory subset than in naive cells. Indeed, in 9 of 25 chronic carriers analyzed, no viral DNA could be detected in naive cells, and in many other cases the low signals could well be explained by low level contamination with memory cells. Even in acute IM, as already reported,13 switched memory loads were very much higher (median, 180-fold) than in the naive B-cell subset, the latter's low signals again likely arising through contamination. Interestingly, however, viral DNA was also often detected in the nonswitched memory B-cell fraction of both IM patients and chronic carriers, median levels being, respectively, just 2.5-fold and 4.5-fold lower than the corresponding switched memory loads. The individual results in Table 1 show that the nonswitched memory load ranged from 5% to 42% (mean, 23%) of the corresponding isotype-switched memory load in all 6 IM patients tested. Likewise, 12 of the 17 chronic carriers tested gave nonswitched memory loads ranging from 5% to 64% (mean, 20%) of the switched memory value. Given the purity of the nonswitched memory sorts, such results cannot be wholly ascribed to contamination with switched memory cells. Of the other 5 carriers tested, 2 (CC19, CC24) had no detectable signals in nonswitched memory cells, one (CC26) gave a low value close to that seen in the same donor's naive cells, and another (CC21) gave a value that was 3% of the same donor's switched memory load. Intriguingly, in the remaining person (CC20, a healthy carrier with a normal B-cell subset distribution in peripheral blood), the virus was clearly present in the nonswitched memory subset but, uniquely, was undetectable in isotype-switched memory.

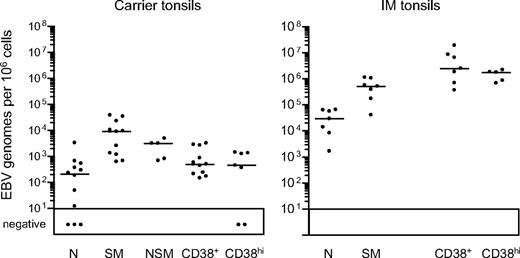

EBV genome loads in peripheral blood B-cell subsets. EBV genome loads in purified naive (N), isotype-switched memory (SM), and nonswitched memory (NSM) B cells were determined by quantitative PCR and the results expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells. Median values for each subset (shown by the horizontal bars) are 6.0 × 101, 5.0 × 103, and 1.1 × 103, respectively, for chronic virus carriers, and 3.9 × 103, 7.0 × 105, and 2.8 × 105, respectively, for IM donors. Restricting the analysis to those persons in which all 3 subsets were sorted, median values were unchanged for chronic carriers and 4.6 × 103, 9.9 × 105, and 2.8 × 105, respectively, for IM donors. Samples with less than 10 copies per 106 cells are reported as negative.

EBV genome loads in peripheral blood B-cell subsets. EBV genome loads in purified naive (N), isotype-switched memory (SM), and nonswitched memory (NSM) B cells were determined by quantitative PCR and the results expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells. Median values for each subset (shown by the horizontal bars) are 6.0 × 101, 5.0 × 103, and 1.1 × 103, respectively, for chronic virus carriers, and 3.9 × 103, 7.0 × 105, and 2.8 × 105, respectively, for IM donors. Restricting the analysis to those persons in which all 3 subsets were sorted, median values were unchanged for chronic carriers and 4.6 × 103, 9.9 × 105, and 2.8 × 105, respectively, for IM donors. Samples with less than 10 copies per 106 cells are reported as negative.

To check that these virus load values actually reflected the absolute numbers of infected cells in the different B-cell subsets (and were not skewed by intersubset differences in mean genome load per infected cell), we performed a limiting dilution DNA PCR analysis on sorted populations from 5 persons. The results (Table S1) show that the frequencies of EBV-infected cells in the 3 subsets are indeed broadly in line with total virus loads.

Tonsillar B-cell subsets in primary and persistent infection

We then examined the greater range of phenotypically distinct B-cell subsets in tonsillar preparations,7,23 again comparing chronic carrier with acute IM tonsils.22 As shown in Figure 3A, the percentage of CD20+ B cells varied widely in both groups, but median values were not significantly different between the two. Tonsillar B cells were then enriched to more than 95% purity by anti-CD3-based T-cell depletion and triple-stained with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD38, FITC-conjugated anti-IgD, and PE-conjugated anti-CD27 to identify 5 distinct subsets: CD38+ (typically GC) cells, CD38hi plasma cells and, from the CD38− fraction, the naive, isotype-switched memory and nonswitched memory subsets distinguished by IgD/CD27 status. Chronic carrier tonsils showed a typical subset distribution, with naive B cells as the largest population, followed by switched memory and CD38+ cells, and with very small numbers of CD38hi cells; note also that a nonswitched memory cell population was always detectable in these tonsils but was not as abundant as in blood. Acute IM tonsils showed a broadly similar distribution but with a tendency toward more isotype-switched and fewer nonswitched memory cells.

Characterization and isolation of tonsillar B-cell subsets based on CD38/IgD/CD27 staining. (A) Tonsillar mononuclear cells were stained with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD20 mAbs to enumerate the percentage of B cells in tonsils from chronic virus carriers (CCT) and IM patients (IMT). Purified B cells were triple-stained with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD38, FITC-conjugated anti-IgD, and PE-conjugated anti-CD27 Abs to enumerate the percentages of CD38+ and CD38hi cells, and from the CD38− fraction, IgD+CD27− naive, IgD−CD27+ isotype-switched memory and IgD+CD27+ nonswitched memory subsets. Median values for each group are shown by the horizontal bars; there were no statistical differences in the proportion of each subset between chronic carrier and IM tonsils. (B) Purified tonsillar B cells were separated into the 5 subsets shown in panel A using the indicated sort gates and the isolated B-cell populations subsequently reanalyzed to determine the sort purities. Shown are representative data from donor CCT8.

Characterization and isolation of tonsillar B-cell subsets based on CD38/IgD/CD27 staining. (A) Tonsillar mononuclear cells were stained with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD20 mAbs to enumerate the percentage of B cells in tonsils from chronic virus carriers (CCT) and IM patients (IMT). Purified B cells were triple-stained with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD38, FITC-conjugated anti-IgD, and PE-conjugated anti-CD27 Abs to enumerate the percentages of CD38+ and CD38hi cells, and from the CD38− fraction, IgD+CD27− naive, IgD−CD27+ isotype-switched memory and IgD+CD27+ nonswitched memory subsets. Median values for each group are shown by the horizontal bars; there were no statistical differences in the proportion of each subset between chronic carrier and IM tonsils. (B) Purified tonsillar B cells were separated into the 5 subsets shown in panel A using the indicated sort gates and the isolated B-cell populations subsequently reanalyzed to determine the sort purities. Shown are representative data from donor CCT8.

Viral loads in tonsillar B cells and B-cell subsets

As shown in Figure S1, for chronic carriers the median viral genome load in tonsillar B cells was similar to that seen in the circulating B-cell pool. However, in IM, the tonsillar B-cell load was not only almost 1000-fold higher than chronic carrier values but also 10-fold higher than seen in IM blood. To ask whether lytic virus replication within IM tonsillar B cells was contributing to such high loads, we screened RNA from available aliquots of 2 × 105 cells from each of 4 IM tonsil B-cell preparations for evidence of EBV lytic gene expression, using quantitative RT-PCR assays of immediate early and late gene transcription that are capable of detecting a single lytically infected cell25,26 ; cellular GAPDH mRNA was assayed in parallel to confirm RNA quality. In some tonsils, we detected trace signals of BZLF1 (immediate early) transcription but never detected any BVRF2 or BLLF1 late gene transcripts, a result consistent with earlier immunostaining work that found occasional BZLF1-positive cells in IM tonsils but no clear evidence of cells completing lytic cycle.3 Hence, virus loads in IM tonsillar B cells are taken to reflect the burden of latently infected cells in that population.

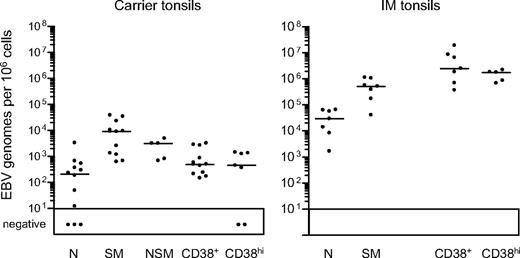

Tonsillar B-cell subsets were then isolated by FACS sorting. As shown in Figure 3B, the CD38hi cell fraction typically gave purities of more than 96%, the CD38+ fraction more than 97%, and the naive and switched memory fractions more than 99% and more than 97%, respectively. Note that the small size of the nonswitched memory compartment precluded its isolation from some chronic carrier and from all IM tonsils; however, where sorted populations were obtained, purities were always more than 95%. Figure 4 summarizes the EBV genome loads found in the sorted populations, with detailed results from individual tonsils in Table 2. In chronic carrier tonsils, the highest virus load was in the switched memory population, the median value being more than 40-fold higher than that for naive B cells. As in the blood, however, we also detected infection of the nonswitched memory subset. Of 5 tonsils analyzed, the nonswitched memory load in 2 (CCT8 and CCT14) was approximately 50% and in a third (CCT12) was higher than that seen in the corresponding switched memory population. Interestingly, in most cases both the GC population (as defined by CD38+ status) and the plasma cell population (CD38hi) carried low virus loads, median values being only 2-fold higher than that seen in the corresponding naive subset and well below that seen in switched memory cells.

EBV genome loads in tonsillar B-cell subsets isolated by CD38/IgD/CD27 sorting. EBV genome loads in naive (N), isotype-switched memory (SM), nonswitched memory (NSM), CD38+ and CD38hi B-cell subsets were determined by quantitative PCR and the results expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells. Median values for each group (shown by the horizontal bars) are 2.1 × 102, 9.1 × 103, 3.1 × 103, 4.9 × 102, and 4.5 × 102, respectively, for chronic carrier tonsils, and 2.9 × 104, 5.2 × 105, not determined, 2.5 × 106 and 1.8 × 106, respectively, for IM tonsils.

EBV genome loads in tonsillar B-cell subsets isolated by CD38/IgD/CD27 sorting. EBV genome loads in naive (N), isotype-switched memory (SM), nonswitched memory (NSM), CD38+ and CD38hi B-cell subsets were determined by quantitative PCR and the results expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells. Median values for each group (shown by the horizontal bars) are 2.1 × 102, 9.1 × 103, 3.1 × 103, 4.9 × 102, and 4.5 × 102, respectively, for chronic carrier tonsils, and 2.9 × 104, 5.2 × 105, not determined, 2.5 × 106 and 1.8 × 106, respectively, for IM tonsils.

The parallel data from IM tonsils show a fundamentally different distribution. Virus loads per 106 cells were almost always highest in the CD38+ fraction and in CD38hi plasma cells. The isotype-switched memory subset also had significant loads, although median values were 5-fold lower than in the CD38+ fraction whereas the median naive cell load was a further 20-fold lower. Because CD38hi plasma cells constitute a very small proportion of IM tonsillar B cells (Figure 3), the bulk of the virus load therefore lies in the numerically dominant CD38+ population and, to some extent, in the switched memory subset. Although CD38 expression at intermediate levels is a useful marker for GC cells in chronic carrier tonsils,23,30 this marker is also up-regulated to similar levels on B cells transformed by the virus in vitro.31,32 We therefore asked whether the high EBV loads in CD38+ IM tonsillar B cells truly reflected concentration of the infection in cells with a classic GC phenotype.

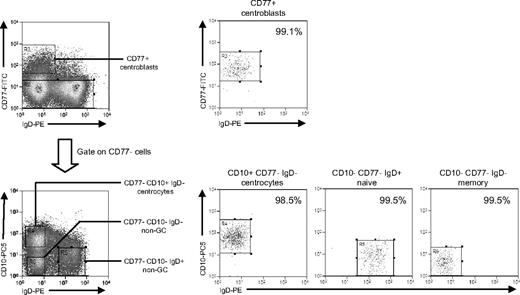

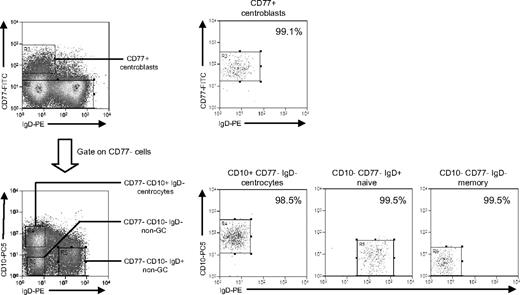

This required a different sort strategy using (alongside IgD) CD77 as a centroblast marker and CD10 as a pan-GC marker also capable of detecting CD77− centrocytes.30 Additional aliquots of tonsillar B cells from 3 IM donors (IMT3, IMT6, IMT8) and 2 chronic carriers (CCT12, CCT13) were triple-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD77, PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD10, and PE-conjugated anti-IgD mAbs. This allowed separation into CD77+ centroblasts, CD77−CD10+ centrocytes, and 2 populations of non-GC (CD77−CD10−) B cells distinguished as IgD+ and IgD−; note that the IgD+ non-GC population will be dominated by naive cells (because IgD+ nonswitched memory cells are relatively rare in tonsils) and the IgD− population by isotype-switched memory cells. Representative FACS staining profiles, sort gates, and quality are illustrated in Figure 5. Centroblasts, naive, and switched memory populations were always more than 96% pure, whereas centrocyte purity ranged from 90% to 99% in 4 cases but was only 80% in one case (IMT3).

Isolation of tonsillar B-cell subsets based on CD77/CD10/IgD staining. Purified tonsillar B cells were triple-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD77, PE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD10, and PE-conjugated anti-IgD mAbs to identify CD77+ centroblasts, and from the CD77− fraction, CD10+IgD− centrocytes, CD10−IgD+ non-GC cells (predominantly naive B cells), and CD10−IgD− non-GC cells (predominantly memory B cells) and then separated using the indicated sort gates. Isolated B-cell subsets were subsequently reanalyzed to determine the sort purities. Shown are representative data from donor CCT13.

Isolation of tonsillar B-cell subsets based on CD77/CD10/IgD staining. Purified tonsillar B cells were triple-stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD77, PE-Cy5–conjugated anti-CD10, and PE-conjugated anti-IgD mAbs to identify CD77+ centroblasts, and from the CD77− fraction, CD10+IgD− centrocytes, CD10−IgD+ non-GC cells (predominantly naive B cells), and CD10−IgD− non-GC cells (predominantly memory B cells) and then separated using the indicated sort gates. Isolated B-cell subsets were subsequently reanalyzed to determine the sort purities. Shown are representative data from donor CCT13.

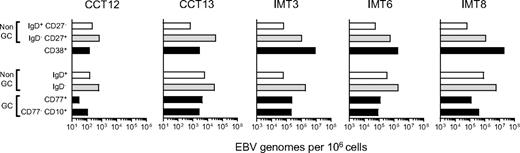

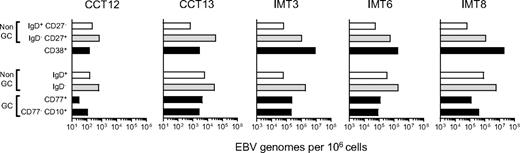

Figure 6 shows the viral loads detected in CD77/CD10/IgD-sorted populations (lower 4 bars) alongside loads obtained earlier for the CD38+ fraction and for CD38− naive and memory cells from the same tonsils (upper 3 bars). Note the difference in scale used for chronic carrier and IM tonsils (101-106 and 103-108 viral genomes per 106 cells, respectively). In both carrier tonsils, the low load seen earlier in the CD38+ population was very similar to the load now detected in CD77+ centroblasts and CD77− CD10+ centrocytes (black bars). By contrast, in all 3 IM tonsils, the very high load seen earlier in the CD38+ population was 20- to100-fold greater than the centroblast and centrocyte loads. Clearly, most of the high viral load in these IM tonsils was concentrated in CD10−CD77− non-GC cells, particularly in the CD10−CD77−IgD− (memory, gray bars) fraction. The implication is that IM tonsillar B cells must contain significant numbers of CD38+ cells in addition to the GC compartment. In that regard, Table 3gives the relative sizes of the CD77/CD10/IgD-defined cell populations in the 5 donor tonsils studied, and the size of their CD38+ population. In 2 chronic carrier tonsils, the combined size of CD77+ centroblast and CD10+ centrocyte populations was roughly equivalent to that of the CD38+ B-cell fraction (14% vs 9% in CCT12 and 30% vs 36% in CCT13). By comparison, in the 3 IM tonsils, centroblasts and centrocytes made up a much smaller fraction of the total B cells, and their combined size was always significantly lower than that of the CD38+ population (5% vs 9%, 10% vs 28%, and 6% vs 22% in IMT3, IMT6, and IMT8, respectively).

EBV genome loads in tonsillar B-cell subsets isolated by alternative sorting strategies. Duplicate samples from 2 chronic carrier tonsils (CCT12, 13) and from 3 IM tonsils (IMT3, 6, 8) were sorted independently using 2 different protocols. For each tonsil, (1) the top 3 bars indicate EBV genome loads in subsets isolated by CD38/IgD/CD27 sorting into purified naive (CD38−, IgD+,CD27−, □), isotype-switched memory (CD38−, IgD−, CD27+ gray bars), and CD38+ (■) B-cell subsets, and (2) the bottom 4 bars show corresponding data for subsets isolated by CD77/CD10/IgD sorting into CD10−, CD77− non-GC cells that are IgD+ (□) or IgD− ( ), CD77+ centroblasts and CD10+ CD77− centrocytes (■). Viral loads are expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells.

), CD77+ centroblasts and CD10+ CD77− centrocytes (■). Viral loads are expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells.

EBV genome loads in tonsillar B-cell subsets isolated by alternative sorting strategies. Duplicate samples from 2 chronic carrier tonsils (CCT12, 13) and from 3 IM tonsils (IMT3, 6, 8) were sorted independently using 2 different protocols. For each tonsil, (1) the top 3 bars indicate EBV genome loads in subsets isolated by CD38/IgD/CD27 sorting into purified naive (CD38−, IgD+,CD27−, □), isotype-switched memory (CD38−, IgD−, CD27+ gray bars), and CD38+ (■) B-cell subsets, and (2) the bottom 4 bars show corresponding data for subsets isolated by CD77/CD10/IgD sorting into CD10−, CD77− non-GC cells that are IgD+ (□) or IgD− ( ), CD77+ centroblasts and CD10+ CD77− centrocytes (■). Viral loads are expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells.

), CD77+ centroblasts and CD10+ CD77− centrocytes (■). Viral loads are expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells.

EBER+ CD38+ cells located on IM tonsil sections

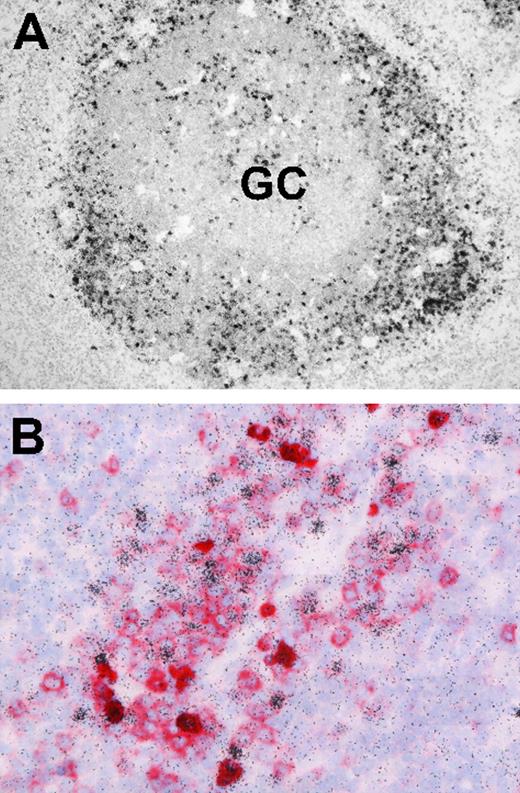

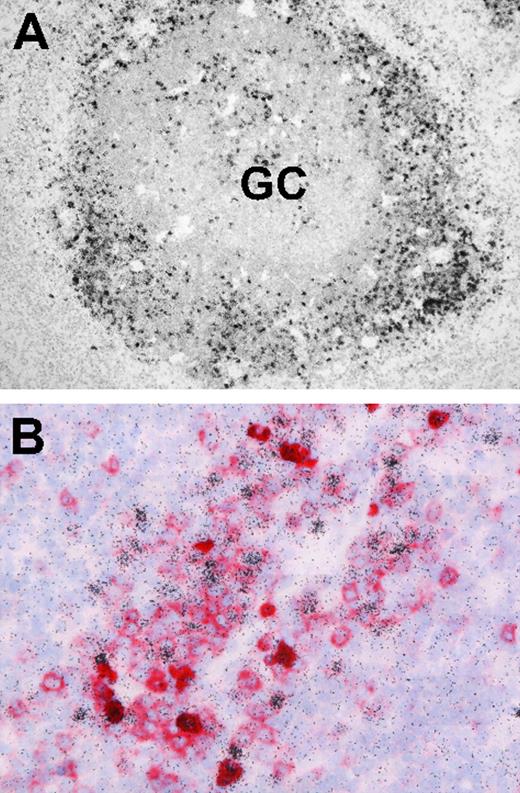

Finally, we asked whether EBV-infected B cells in IM tonsils, although reportedly concentrated outside GC structures, were indeed frequently CD38+. Screening archival IM tonsil sections by EBER-specific in situ hybridization first confirmed that, by far, the majority of EBER-positive cells have an extrafollicular location (Figure 7A). Thereafter, EBER/CD38 double stains (Figure 7B) found many of these EBER-positive cells gave typical CD38 membrane staining.

Localization and phenotype of EBV-positive cells in IM tonsil sections. (A) EBER-specific in situ hybridization with 35S-labeled RNA probes reveals numerous extrafollicular EBV-positive cells (black granular labeling). A small number of EBV-positive cells are also present within the GC. (B) Double labeling reveals that a proportion of extrafollicular EBV-positive cells (black) coexpress CD38 (red). Sections were examined under a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany) using either a Nikon Plan Apochromat 10×/0.45 objective lens (panel A) or a Nikon Plan Apochromat 40×/0.95 objective lens (panel B). Digital images were obtained with a Nikon Digital DS-5M camera and acquired using Digital Sight DS-5M-L1 image acquisition software.

Localization and phenotype of EBV-positive cells in IM tonsil sections. (A) EBER-specific in situ hybridization with 35S-labeled RNA probes reveals numerous extrafollicular EBV-positive cells (black granular labeling). A small number of EBV-positive cells are also present within the GC. (B) Double labeling reveals that a proportion of extrafollicular EBV-positive cells (black) coexpress CD38 (red). Sections were examined under a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany) using either a Nikon Plan Apochromat 10×/0.45 objective lens (panel A) or a Nikon Plan Apochromat 40×/0.95 objective lens (panel B). Digital images were obtained with a Nikon Digital DS-5M camera and acquired using Digital Sight DS-5M-L1 image acquisition software.

Discussion

The original finding that EBV persistence in the healthy virus-carrying host involves selective colonization of circulating memory but not naive B cells14,15 has fueled debate as to how that selectivity is achieved in vivo. Much of that debate rests on a single issue, whether the entry of EBV-infected B cells into memory does or does not involve GC transit (ie, the physiologic pathway of antigen-driven memory B-cell generation).19,20 Here we attempt to inform that debate in 2 ways: (1) by asking whether EBV can access a nonswitched memory cell population that may arise independently of GC activity; and (2) by separating B cells from IM tonsil cell suspensions into subsets based on GC-associated markers and examining the subset distribution of EBV-infected cells.

The possibility that EBV might colonize nonswitched as well as isotype-switched memory cells in immunocompetent persons was prompted by a recent study of X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP) patients.26 In this condition, the absence of a functional SAP protein abrogates CD4+ T-cell help for antibody responses,33 resulting in a lack of detectable GC formation and of isotype-switched memory B cells.34,35 Nevertheless, these patients, like CD40 ligand-deficient persons similarly lacking GCs and switched memory B cells,9 still possess circulating nonswitched memory B cells, albeit in lower numbers than usual.34 We found that XLP patients who survive primary EBV infection establish a stable carrier state in which the virus is concentrated in that small nonswitched memory fraction.26 However, it was not clear whether this colonization of nonswitched memory is peculiar to XLP or is highlighting a general feature of EBV infection that in healthy carriers is masked by the high viral loads in switched memory. Here we addressed this by sorting the 3 main B-cell subsets from the blood of immunocompetent persons. First we confirmed the published findings13,14 that, both in primary and persistent infection, viral load is much greater (frequently > 100-fold) in isotype-switched memory cells than in the naive subset. However, all 6 IM patients studied also had significant EBV loads in nonswitched memory B cells, ranging from 5% to 42% of that seen in switched memory cells. Although we did not see the same uniformity of results among chronic carriers, nevertheless, 12 of 17 carriers tested gave nonswitched memory loads 5% to 64% of switched memory values, and in another carrier the virus was concentrated in the nonswitched memory subset. Such results probably do not reflect cellular contamination of nonswitched memory populations because FACS analysis showed these to be consistently more than 97% pure; indeed, most contaminating cells had an IgD+CD27− naive phenotype and less than 1% of the sorted population had an IgD−CD27+ switched memory phenotype (Figures 1B, 3B). Furthermore, although the nonswitched memory subset is less abundant in tonsils than in blood, we were able to sort these cells to a purity of more than 95% from 5 chronic carrier tonsils. All 5 showed significant EBV loads in the nonswitched subset, and in 3 of 5 cases the load was 50% or more of that seen in isotype-switched cells, levels that, again, appear too high to be explained by contamination from other subsets.

We infer that EBV does colonize the nonswitched memory B-cell pool in the blood of a substantial number of persons, albeit not as efficiently as it does the switched memory population. This finding appears in contrast to the existing literature. Thus, an earlier report found no evidence for EBV infection within circulating IgD+CD27+ cells, albeit from data on only 3 healthy virus carriers.15 In the original study of IM donors,13 the implied selective colonization of isotype-switched memory was based on sorting of B cells into CD27+ and CD27− fractions in 2 subjects, with virus concentrated in CD27+ cells, and into IgD+ and IgD− fractions in 4 other subjects, with virus concentrated in IgD− cells. In this latter case, viral infection of nonswitched memory cells could have been masked in an IgD+ population where naive cells constitute a large majority. Two more recent studies36,37 have addressed the issue further by screening single cells from phenotypically sorted B-cell subsets from IM blood, detecting EBV-positive cells by RT-PCR for EBER expression and then amplifying their Ig transcripts. In the first study, among the 5 or 6 such cells examined per patient, all expressed mutated Ig transcripts and most were of Ig γ or α isotype; however, infected cells expressing mutated μ transcripts were detected in 3 of 6 patients tested.36 In the second study of 3 IM patients, 3%, 10%, and 27% of transcripts from EBV-infected cells in the CD27+ fraction were of Igμ isotype.37 Whether such cells derive from nonswitched memory cells (IgD+IgM+CD27+) or, as the authors suggest, from the much rarer IgM-only population (IgD−IgM+CD27+) remains unclear because in at least one of these patients the level of virus detectable in the IgD+ memory fraction could not be explained by contamination from the IgD− memory pool. The in vivo interaction between EBV and nonswitched memory cells in healthy donors therefore deserves further attention. At this point, we would stress that the origin of IgD+CD27+ B cells is currently unresolved.11 However, if this entire population is truly GC-independent, as some argue,10,11,38 our data would suggest that the virus can establish persistence in at least one memory B-cell subset without requiring GC transit and that this phenomenon is not peculiar to patients with specific immunodeficiencies26 but is also the case in at least some immunocompetent persons.

A second approach to the study of EBV-GC interactions came through access to cryopreserved cell suspensions from IM tonsils.22 This allowed, for the first time, the distribution of EBV among IM tonsillar B-cell subsets to be studied by cell sorting. We began by validating the CD38/IgD/CD27-based sort procedures on chronic carrier tonsils and confirmed the published finding17 that EBV preferentially colonizes the CD38− IgD−CD27+ isotype-switched B-cell subset at levels similar to isotype-switched cells in the blood. By comparison, the levels seen in CD38+ (predominantly GC) cells or in CD38hi plasma cells of the same tonsils were very low, on average only 2-fold above that detected in naive B-cell preparations. However, in contrast to that earlier study, we found no tonsils with evidence of the ongoing EBV replication in B cells and so could not check the reported association between virus replication, naive B-cell infection, and the detection of virus-positive cells in the GC fraction.17

Applying this same sort procedure to IM tonsils, virus loads were not only several logs higher than in chronic carrier tonsils, but the virus distribution between subsets based on CD38/IgD/CD27 staining was different. Now the CD38+ subset, nominally composed of GC cells, and the minor CD38hi plasma cell subset had the highest concentration of virus loads, with switched memory cells consistently lower and with naive cells lower still. To identify the major population of EBV-positive CD38+ cells in more detail, we adopted a different sort strategy yielding CD77+ centroblasts, CD10+ centrocytes, and 2 subsets of CD77−CD10− (non-GC) cells, namely, IgD+ (principally naive) and IgD− (switched memory). We found the virus concentrated in the non-GC fraction, particularly in the IgD− memory cells. This accords with the observation that most EBV-positive cells micromanipulated from IM tonsil sections are members of expanding clones with stable memory genotypes, with only a few isolated cells showing a naive genotype.4 Importantly, EBV loads were low in the CD77+ or CD10+ sorts, indicating that the bulk of EBV-infected cells, although expressing CD38, do not display other markers typical of GCs. We therefore infer that the CD38+ status of EBER-positive cells, detectable in the extrafollicular areas of IM tonsils on stained sections, reflects the growth activation of these cells and not their ectopic acquisition of a GC-like phenotype. Note that the extrafollicular EBER-positive population as a whole was heterogeneous for CD38 expression, as one would expect given that this population is also heterogeneous with respect to expression of the EBV growth-transforming proteins and degrees of activation to the lymphoblastoid cell line-like state.3,4

The cell sorting data from IM tonsils therefore suggest that, during the acute phase of the disease, there are very few EBV-infected B cells either in the naive B-cell fraction or in the GC population; the majority of the infected cells have a memory phenotype, and many of these express CD38 as a marker of activation. Therefore, if primary EBV infection does initially target naive B cells and drive them through a GC reaction into memory, that process must be essentially complete (with EBV latent protein expression perhaps having abolished the GC phenotype39,40 ) before the onset of IM disease symptoms. Granted this possibility, it is nevertheless surprising that no remnants of that process still remain in IM, given that high levels of virus replication and oropharyngeal virus shedding (albeit from an as-yet-unidentified cell type) go on undiminished throughout the disease episode and afterward,41,42 implying that de novo B-cell infections should still be occurring at this time. It is also interesting to note the contrast between these findings and the process of B-cell colonization by mouse herpesvirus MHV68, a gamma-2 herpesvirus that, like EBV, establishes persistence in memory B cells43,44 but, unlike EBV, lacks intrinsic B-cell-transforming activity. That virus clearly does exploit GC transit during primary infection of the host, and the presence of large numbers of MHV68-infected GC cells can be easily detected over the first few weeks after infection both in spleen tissue sections by in situ hybridization for virus-coded tRNAs45 and in isolated B-cell subsets by genome amplification.43 Moreover, even though the overall viral genome load within the B-cell pool then falls quite rapidly to a much lower level with no detectable ongoing virus replication, MHV68-infected B cells remain evenly distributed between the GC and memory B-cell subsets throughout the carrier state.43,44 This contrasts with the situation in human chronic carrier tonsils where GC loads are usually extremely low.

This is not to deny that EBV can colonize GC populations in circumstances other than acute IM; histologic studies have detected rare GCs dominated by EBER-positive cells in lymphoid tissues of AIDS patients46 or containing EBV antigen-positive cells in tonsils from children subject to chronic antigen stimulation from parasitic infections.47 Such findings may be relevant to the increased risk that both the aforementioned sets of patients have of developing EBV-positive Burkitt lymphoma, a tumor of GC origin.48 This occasional recruitment of EBV-infected cells into GC reactions during life-long virus carriage may be an inevitable consequence of the viral strategy for persistence in the B-cell system. However, from the present work and earlier studies, there is still no clear evidence that GC transit is involved in the initial colonization of EBV of the host. Further progress requires model systems, for example, human lympho–reconstituted mice, in which these events can be analyzed.49 In a first study of this kind,50 infection led either to diffuse proliferations of EBV-infected B cells that effaced normal lymphoid architecture or to follicular hyperplasia but with EBV-infected cells largely found, as in IM, at extrafollicular sites. Such findings raise the hope of studying EBV/B-cell interactions experimentally in vivo.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients for their participation in this study.

This work was supported by a grant from Cancer Research UK (A.B.R.) and a Leukemia Research Fund Clinical Research Fellowship (S.C.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.C., E.M.H., M.B., G.N., and A.I.B. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; M.K. and W.B. provided clinical samples; S.C., G.N., and A.I.B. prepared the figures; A.B.R. designed the research; and S.C., A.I.B., and A.B.R. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alan B. Rickinson, Cancer Research UK Institute for Cancer Studies, University of Birmingham, Vincent Dr, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, United Kingdom; e-mail: a.b.rickinson@bham.ac.uk.

), CD77+ centroblasts and CD10+ CD77− centrocytes (■). Viral loads are expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells.

), CD77+ centroblasts and CD10+ CD77− centrocytes (■). Viral loads are expressed as EBV genomes per 106 cells.