Abstract

Although uncontrolled proliferation is a distinguishing property of a tumor as a whole, the individual cells that make up the tumor exhibit considerable variation in many properties, including morphology, proliferation kinetics, and the ability to initiate tumor growth in transplant assays. Understanding the molecular and cellular basis of this heterogeneity has important implications in the design of therapeutic strategies. The mechanistic basis of tumor heterogeneity has been uncertain; however, there is now strong evidence that cancer is a cellular hierarchy with cancer stem cells at the apex. This review provides a historical overview of the influence of hematology on the development of stem cell concepts and their linkage to cancer.

Introduction

Tumors from different patients, whether leukemic or solid, exhibit significant heterogeneity in terms of morphology, cell surface markers, genetic lesions, cell proliferation kinetics, and response to therapy. Heterogeneity of all these features is also seen within an individual tumor that is clonal (ie, initiated from a single cell). Although individual cells of a tumor all share common genetic aberrations reflective of their clonal origin, single-cell analysis has shown the existence of variation in genetic and epigenetic abnormalities between different cells or locations within a tumor. The cellular and molecular basis for this heterogeneity represents a fundamental problem that has interested cancer researchers for many decades. One possible explanation is that all tumor cells could be biologically equivalent and heterogeneity derives from extrinsic or intrinsic influences that result in random or stochastic responses. Alternatively, it is possible that the tumor is a caricature of normal tissue development and retains hierarchical organization with (cancer) stem cells at the apex.1 This review will focus on 50 years of hematology research that played a role in garnering evidence to support the hierarchy model

There is mounting evidence from cell purification studies that a subset of cells, termed cancer stem cells (CSCs), or cancer-initiating cells, that are distinct from the bulk of the tumor are responsible for long-term maintenance of tumor growth in several cancers.2 Evidence is strongest for the acute leukemias, although recent studies have identified the existence of CSCs in an increasingly longer list of solid tumors, including brain, breast, and colon.3 This conceptual shift has important implications, not only for researchers seeking to understand mechanisms of tumor initiation and progression but also for developing and evaluating effective anticancer therapies. Although the clinical relevance of CSCs beyond experimental models is still lacking, the high frequency of relapse after conventional cytotoxic chemotherapies predicts that CSCs survive standard treatments. Many papers, reviews, and funding bodies are making strong predictions that targeting CSCs more effectively will lead to improved patient outcomes. Indeed, there has been almost breathless excitement that this “new” field of CSC biology will solve the stubbornly high relapse rates that continue to exist for many cancers. However, stem cell concepts and how they apply to cancer are decades old, and many obstacles to the development of effective anticancer therapies still exist. It is important to understand the historical underpinnings of the CSC field to recognize the challenges we still face. By understanding where we came from, we will have a clearer view of the way forward. The history of stem cell research, and cancer stem cell research in particular, is long and better suited for a book rather than a short review. Thus, I only touch on a few highlights that I find significant and that played a role in guiding our own work in this field; most of my comments revolve around studies in hematopoiesis and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) specifically. My apologies go to those whose work I was not able to include or could only be treated in a superficial fashion.

Tumor heterogeneity

The notion that cancer is a disease of abnormal or uncontrolled proliferation has governed cancer research for more than 7 decades. Because normal tissues also undergo continuous regeneration, albeit at rates specific to each organ, the historical thrust of cancer research was to develop drugs that targeted the enhanced rate of neoplastic proliferation. Clinicians used doses and schedules that achieved many log orders of cell kill while maintaining acceptable levels of toxicity to normal tissues. Based on a deep understanding of the molecular basis of cancer, current therapeutic strategies now focus on inhibiting the molecular drivers of cancer (eg, trastuzumab-Her2/Neu, imatinib-bcr/abl, erlotonib, epidermal growth factor receptor). With an increased appreciation of the extrinsic microenvironmental factors that support tumor growth, such as the vasculature, approaches that interfere with these factors (ie, bevacizumab, vascular endothelial growth factor) are also being brought forward. What all these strategies, whether from the past or present, have in common is the tacit perspective of cancer as a homogeneous, abnormal entity. Therefore, drugs targeting molecular lesions should be equally effective against all tumor cells, barring the emergence of resistant subclones. The goal is to ensure that enough drug(s) is given to target the primary molecular pathway and then combined with drugs that target other relevant or compensatory pathways to enable killing of every tumor cell. Indeed, historically, even research to understand the basic biology of cancer uses strategies that treat an individual cancer as functionally homogeneous. Much cancer research, even to the present day, follows a paradigm where the entire tumor or an entire dish of tissue culture cells is used for genetic, proteomic, or biochemical studies, mostly because the technology used to interrogate biologic processes (ie, proteomics, biochemistry) cannot be done on single cells and requires large cell numbers. Clearly, this has been a productive approach as evidenced by the thorough understanding gained on the genetic and epigenetic basis of the neoplastic process. However, an inability to deal meaningfully with limiting cell numbers has forced the cancer research enterprise to operate within a dichotomy because it is also well known that tumors are not homogeneous but exhibit significant heterogeneity.

Since the time of the great experimental pathologists (Virchow, Maximov, and others), it has been recognized that tumors, be they liquid or solid, exhibit marked morphologic heterogeneity. With the advent of transplantation of murine cancer cell lines into mice, Furth and Kahn in 1937 were able to establish that a single cell, and not a transmissible agent, could initiate a cancer graft.4 As others applied transplantation assays to a variety of solid tumors and leukemias throughout the next several decades, it became clear that there was wide variation in the frequency of cells that initiate cancer growth.5-7 Remarkably, human studies have been carried out since the late 1800s (reviewed by Southam et al8 ) where tumors were excised, single-cell suspensions made and autotransplanted into the thigh at different cell doses. These studies showed that tumor reinitiation was variable and rare, often requiring more than 106 cells. Finally, in an elegant series of experiments, Pierce et al showed that malignant teratocarcinoma cells can spontaneously differentiate into mature benign cells.9 Thus, a tumor can be considered a hierarchy defined by a maturation process in the same way that normal tissue development occurs. In 1961, Pierce and Speers proposed the idea that tumors are caricatures of normal development and that this maturation process could be harnessed as a means of therapy.10

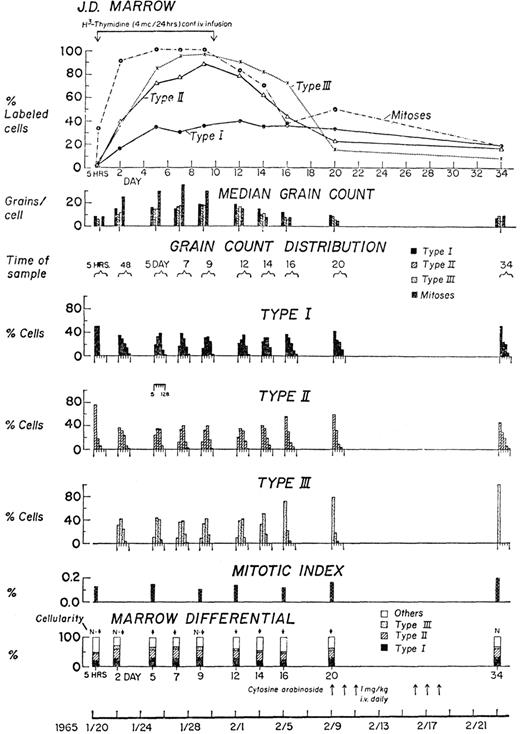

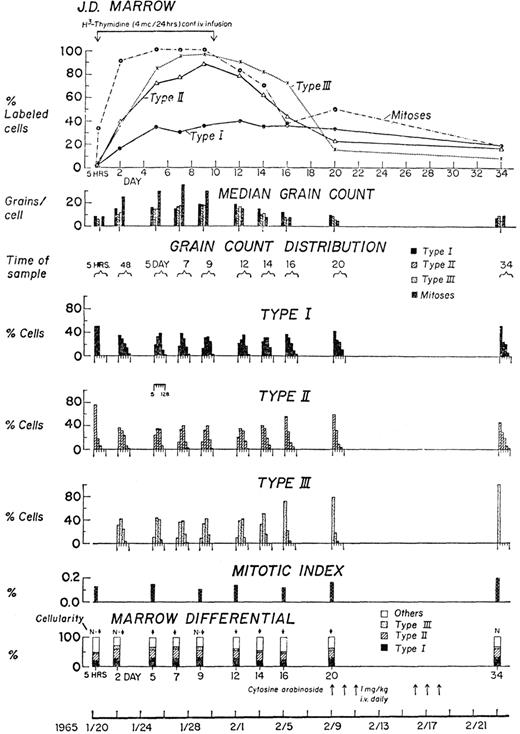

The concept of cellular heterogeneity reached its zenith with the functional cell proliferation studies of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The advent of radiolabeling cells, combined with autoradiography by Belanger and Leblond in 1946, enabled precise measurements of the proliferation, lifespan, and hierarchical relationships in normal and neoplastic tissues.11 Clermont and Leblond showed, for example, that the testis contained proliferating cells that took up a pulse of label and then by tracking the label showed their differentiation to mature cells.12 ; they also noted that these cells maintained themselves. In the 1960s and 1970s, several prominent hematologists, including Clarkson et al,13,14 Killmann et al,15 Gavosto,16 and others, carried out pioneering studies that were (perhaps more than any other findings) the studies establishing that tumors exhibited functional heterogeneity. These were cytokinetic studies carried out first in cell lines and murine models of the acute leukemias and then, remarkably by in vivo examination of leukemia blast proliferation kinetics in human AML and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients. The in vivo data could not have been clearer; the majority of leukemic blasts were postmitotic and needed to be continuously replenished from a relatively small proliferative fraction17 (Figure 1). Only a small fraction (∼ 5%) of leukemic blasts was rapidly cycling in vivo. However, careful analysis demonstrated that there were 2 proliferative fractions in patients: a larger, fast cycling subset with a 24-hour cell cycle time and a smaller, slow cycling fraction with a dormancy estimated to last from weeks to months. In particular, Clarkson, Rubinow, Skipper and their colleagues inferred that the slow cycling fraction was actually generating the fast cycling fraction and suggested these represented a leukemic stem cell (LSC) population because they had similar cytokinetic properties to those observed for normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).18 They noted that the dormant cells were much smaller in size and had less granularity than the rapidly proliferating fraction, which led to speculation that these cells could represent distinct cellular fractions. Of course, such studies could not prove whether the cycling fractions represented the same population, existing in either a proliferative or a nonproliferative state, or whether these observations point to a hierarchical relationship representing 2 functionally distinct cell types. Even so, based on these observations, reviews of this era predicted that the inability to eradicate the theoretical LSCs represented the cause of relapse and the ultimate failure for antiproliferative chemotherapies, which formed the main chemotherapeutic armament at the time.14,19 Investigators then combined in vivo cytokinetic studies with drug treatment and tailored new therapies based on these findings. They made the interesting observation that LSCs respond to depletion of the leukemia cell mass that occurs when antiproliferative drugs are administered to AML patients. LSCs begin to go into cycle and expand in the same way normal stem cells go into cycle after chemotherapy-induced cytopenias. Thus, they suggested that one way to eliminate dormant LSCs would be to find the window when they cycle to kill them when they are most vulnerable. Indeed, the cytokinetic findings represented the underpinning for pioneering clinical trials carried out by Clarkson and his colleagues at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center that used multiple drugs.20 The fundamental problem investigators faced at this time was the inability to directly identify and assay LSCs, making it impossible to characterize them and harness the acquired knowledge for therapeutic approaches in the future. Pointed comments made at least as early as 1970 predicted that antiproliferative chemotherapy agents would not effectively eradicate these dormant LSCs and that future progress must focus on understanding their properties.17 These remarkably prescient observations retain their potency and freshness even today, nearly 40 years later.

Labeling pattern of leukemic cells in marrow of patient 1. Patient 1, a patient with acute myelomonocytic leukemia, received a continuous 10-day infusion of tritiated thymidine. Leukemic cells were arbitrarily divided into types I, II, and III based on increasing levels of morphologic maturity (type I indicates primitive blast forms; type III, most differentiated cells). At the end of the 10-day infusion, most type II and type III cells were labeled in both marrow (shown here) and blood (not shown), but only 40% of type I cells were labeled, reflecting their slow proliferative rate. Many of the type I cells remained highly labeled for over 3 weeks after the infusion. Reprinted from Clarkson17 by permission.

Labeling pattern of leukemic cells in marrow of patient 1. Patient 1, a patient with acute myelomonocytic leukemia, received a continuous 10-day infusion of tritiated thymidine. Leukemic cells were arbitrarily divided into types I, II, and III based on increasing levels of morphologic maturity (type I indicates primitive blast forms; type III, most differentiated cells). At the end of the 10-day infusion, most type II and type III cells were labeled in both marrow (shown here) and blood (not shown), but only 40% of type I cells were labeled, reflecting their slow proliferative rate. Many of the type I cells remained highly labeled for over 3 weeks after the infusion. Reprinted from Clarkson17 by permission.

The cytokinetic studies drove interest away from the study of bulk leukemias because they were mostly composed of postmitotic blasts. Because there was little that could be done to assay the dormant LSC, attention focused on the development of a clonogenic assay for the rapidly proliferating leukemic cells (AML-colony-forming unit [CFU]) that the in vivo studies had uncovered. McCulloch et al,21,22 Moore and Metcalf et al23,24 , Griffin and Löwenberg,25 and Dicke et al26 pioneered these assays and made detailed insights into their properties. Parallel clonal assays were developed for solid tumor clonogenic progenitors.27 In a key series of experiments, Sabbath et al developed a series of monoclonal antibodies (mAb) directed against myeloid differentiation antigens and assessed the phenotype of the AML-CFU itself by complement mediated lysis followed by clonogenic assay.28 Parallel studies were done with normal cells. The AML-CFU from different patients could be classified into 3 groups: primitive (similar to multipotent normal CFU), early lineage committed (similar to normal day 14 CFU-GM), and late (similar to day 7 CFU-GM). This work established that the AML-CFU were distinct from most leukemic blasts and the leukemic cells within an individual colony could be more differentiated than the individual AML-CFU that originated the colony. These clonal data provided the first strong proof for a hierarchy in AML. Moreover, this work suggested that the different classes of AML-CFU might originate from normal cells at different stages of differentiation.25 McCulloch et al showed additional evidence for heterogeneity with the finding that the AML-CFU were heterogeneous in their serial replating ability, some unable to generate secondary colonies whereas others had high capacity.22,29,30 Because this is an indicator of self-renewal, they predicted that some AML-CFU were more primitive than others. Although the properties of AML-CFU (number, proliferation, drug sensitivity) on their own did not predict clinical disease properties or response to therapy, the secondary replating capacity had better predictive power. The AML-CFU assay was used intensively from the late 1960s to the early 1980s and resulted in many important insights into AML biology. However, the limitations of the assay and the lessons that had been learned from the study of normal hematopoiesis underscored the need for functional in vivo assays to determine whether an LSC, earlier than AML-CFU, existed in AML.

Models of tumor heterogeneity

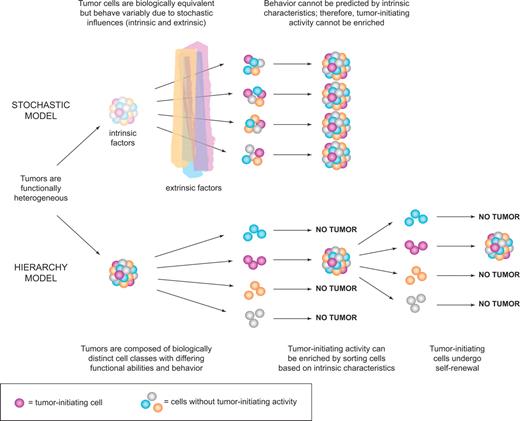

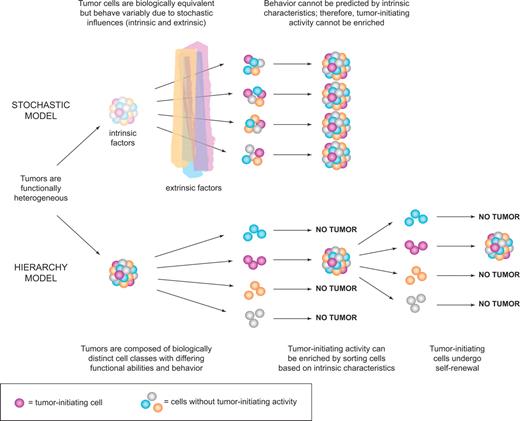

Collectively, the data described in “Tumor heterogeneity” firmly established that tumors are not only morphologically heterogeneous as observed more than 100 years ago, but they are functionally heterogeneous in terms of cell proliferation or even tumor initiation based on transplant assays. Two mutually exclusive models could explain tumor heterogeneity. The stochastic model predicts that a tumor is biologically homogeneous and the behavior of the cancer cells is influenced by intrinsic (eg, levels of transcription factors, signaling pathways) or extrinsic (eg, host factors, microenvironment, immune response) factors. These influences are unpredictable or random and result in heterogeneity in the expression of cell surface markers or other markers of maturation, in entry to cell cycle, or in tumor initiation capacity. A key tenet of this model is that all cells of the tumor are equally sensitive to such stochastic influences and also that tumor cells can revert from one state to another because these influences do not induce permanent changes.1 In contrast, the hierarchy model predicts that the tumor is a caricature of normal tissue development where stem cells maintain normal tissue hierarchies (skin, colon, blood). In this model, the “leukemic stem cells” are biologically distinct, they maintain themselves and the clone by self-renewal, and they mature to generate progeny that lack stem cell properties (Figure 2). Thus, both the stochastic and hierarchy models accommodate the existence of “functional leukemic stem cells,” cells that behave as leukemia stem cells. The essential difference is that, in the stochastic model, LSCs arise randomly and every tumor cell has the potential to behave like an LSC given the right influences; whereas in the hierarchy model, there is only a distinct subset of cells that has the potential to behave like LSCs. The only means to determine which model is correct is prospective isolation of cell fractions followed by clonal analysis with a functional LSC assay. If the hierarchy model is correct, then it should be possible to sort tumors into fractions that have LSC activity and those that do not. In contrast, the stochastic model predicts that LSC activity may be observed in any fraction and cannot be prospectively isolated because all tumor cells have the same potential (even if it is low) for tumor initiation.

Models of tumor heterogeneity. Tumors are composed of phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous cells. There are 2 theories as to how this heterogeneity arises. According to the stochastic model, tumor cells are biologically equivalent, but their behavior is influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors and is therefore both variable and unpredictable. Thus, tumor-initiating activity cannot be enriched by sorting cells based on intrinsic characteristics. In contrast, the hierarchy model postulates the existence of biologically distinct classes of cells with differing functional abilities and behavior. Only a subset of cells can initiate tumor growth; these cancer stem cells possess self-renewal and give rise to nontumorigenic progeny that make up the bulk of the tumor. This model predicts that tumor-initiating cells can be identified and purified from the bulk nontumorigenic population based on intrinsic characteristics.

Models of tumor heterogeneity. Tumors are composed of phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous cells. There are 2 theories as to how this heterogeneity arises. According to the stochastic model, tumor cells are biologically equivalent, but their behavior is influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors and is therefore both variable and unpredictable. Thus, tumor-initiating activity cannot be enriched by sorting cells based on intrinsic characteristics. In contrast, the hierarchy model postulates the existence of biologically distinct classes of cells with differing functional abilities and behavior. Only a subset of cells can initiate tumor growth; these cancer stem cells possess self-renewal and give rise to nontumorigenic progeny that make up the bulk of the tumor. This model predicts that tumor-initiating cells can be identified and purified from the bulk nontumorigenic population based on intrinsic characteristics.

Conditions for discovery

The term “leukemia stem cell” had been in use for many decades, and a large part of the hematology community assumed that the hierarchy model was true and the leukemia clone existed in a hierarchy sustained by an LSC, with obvious parallels to the role that HSCs play in sustaining the normal hematopoietic hierarchy. However, formal proof that LSCs had stem cell attributes and were distinct from the rest of the leukemic cells that could never behave as LSCs was still lacking. Clearly, technologies that were not available in the 1970s were required to move the field forward. However, I do not think the absence of technology can fully explain why lags existed from the mid-1970s when all the theoretical principles pointing to the existence of LSCs and a description of their properties were well worked out, to the mid-1990s when direct proof for the existence of LSC was finally discovered, and then to the most recent years when CSC concepts have been extended to solid tumors. The explanation also rests in the time it took for stem cell concepts to permeate the broader cancer research community and to become more accepted. The research environment was primed with the groundbreaking studies of normal HSCs, eventually leading to HSC transplant as therapy and to the crossover of universal stem cell concepts into many areas of biology. This created a backdrop in which technologies were developing, including the use of flow cell sorters in combination with mAb that bind cell surface markers and the development of human xenograft assays for human HSCs and LSCs. Because these conditions set the stage for discovery of LSCs and eventually CSCs from solid tumors, it is instructive to review the key highlights that culminated to identify HSCs and the universal concepts these stem cell studies generated.

Identification of normal HSCs in the mouse

The modern era of stem cell research can be traced back to the seismic shift in the 1960s when Till and McCulloch moved HSC research from a descriptive science to a quantitative science. Although careful studies using microscopic analysis pointed to the idea of a common stem cell for all blood lineages,31 equally robust was the view that independent stem cells existed for each major blood lineage, which was promulgated by textbooks from the 1940s.32 The experimental finding by Till and McCulloch that the “regeneration nodules” on the spleen of lethally irradiated mice (termed CFU-spleen [CFU-S])33 transplanted with BM cells were clonal (based on X-ray induced chromosomal lineage tracking34 ) and contained multiple blood lineages proved that the hematopoietic system derives from a multipotent HSC rather than from a series of lineage-specific stem cells. With a clonal, quantitative, and functional assay in hand, in short order they established all of the major stem cell principles under which we continue to operate today: HSCs have a high capacity for self-renewal, proliferation, and multipotential differentiation. Their observations that the self-renewal capacity of individual CFU-S was highly variable35 led them to propose the concept that the control of HSC self-renewal was governed by stochastic principles,36 a hypothesis that is still being tested and still able to provoke strong opinions among stem cell biologists.37-41 Their focus on the need for quantitative functional assays prompted the development of in vitro clonal progenitor assays by Pluznik and Sachs42 and Bradley and Metcalf43 that were central to the later discovery of hematopoietic colony stimulating factors (as reviewed in the 50th Anniversary Review by Metcalf44 ). With the use of progenitor assays, it was possible to describe precisely the lineage relationships that occur during maturation. Despite widespread use of the spleen colony assay as a surrogate HSC assay, by the mid 1980s it was clear that a more primitive HSC must exist. First, CFU-S were heterogeneous in terms of their spleen repopulation kinetics.45,46 Second, careful lineage examination showed that the spleen colony was devoid of lymphoid cells and therefore not multipotential.47,48 Third, after 5-fluorouracil treatment, CFU-S were killed whereas other dormant cells capable of CFU-S replenishment survived, suggesting the existence of a pre-CFU-S stem cell.49,50 Harrison, in particular, drove the paradigm that cells with long-term repopulation capacity could be distinguished from those with short-term potential.51 Using chromosomal translocation as a means of cellular marking (first developed by Ford et al52 ), in 1968 the first clonal evidence established multilineage repopulation, including CFU-S and B cells.53 Using the same approach, Abramson et al showed that repopulation of myeloid and lymphoid lineages could derive from a long-term multipotential stem cell or from lineage-restricted stem cells.54 However, the efficiency of marking was low and the need to irradiate the bone marrow to induce chromosomal translocation meant that it was difficult to establish whether the identified HSC classes truly existed or were experimentally induced artifacts. With the development of more benign methods for HSC clonal tracking using retroviral insertion sites, it was possible to establish that long-term, multipotential HSCs existed.55-57 Collectively, these studies established that clonal assays are essential to uncover stem cell properties; and when individual HSCs are assessed, they exhibit wide variations in repopulation dynamics and self-renewal capacity.

Applying universal stem cell concepts to other fields

While these concepts were solidifying, stem cell concepts began to percolate into other research fields through a series of culminating events and set the stage for further discovery. Perhaps the most influential factor that drove stem cell concepts beyond the domain of a small number of stem cell biologists into a wider sphere of biomedical research was the development of HSC transplantation for treatment of leukemia and other hematologic diseases. Through a series of elegant studies in the 1950s, proof was provided that cells (as opposed to a humoral factor) from the bone marrow of mice could protect against lethal doses of radiation by effectively regenerating all of the blood lineages in transplant recipients.52,58 In 1956, Thomas et al carried out the first human bone marrow transplantations,59 although initially a failure, they brought a decade of improvements in tissue typing and methods for controlling graft-vs-host disease. Finally, the pioneering clinical trials of Good, Thomas, and others showed that human BM could be used to cure immune deficiency by sibling donor transplants in 196860 and neoplastic disease in 1969,61 beginning the modern era of human allogeneic marrow grafting. During the same time period, the new field of molecular biology was established. This made it possible not only to use genetics to characterize biologic processes in a much more rapid fashion, but also to produce biologic regulators on an industrial scale. All of these research paths collided in the 1980s with the birth of the biotechnology industry, which was mostly focused on the commercialization of products to stimulate blood cells. Thus, the arcane fields of blood diseases, HSC transplantation, and stem cells in general had moved from a backwater to front stage. The final influence in this fertile period was the discovery of embryonic stem cells by Evans and Kaufman62 and Martin63 in 1981 with the attendant promise of regenerative medicine. Stem cell biology had finally become a hot topic, and it had begun to capture the attention of a broad swath of the research community.

Technology and assay developments

It was within this milieu that 2 important technologic advances took place that directly led to the renewal of interest in the concepts of LSC from 20 years earlier. The first was the development of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and the second was the development of xenotransplantation assays for normal and leukemic human stem cells. Although Miller and Phillips had developed the first large-scale methods for cell separation based on sedimentation,64 these methods lacked the precision needed for meticulous cell fractionation. The development of FACS by Herzenberg's group at Stanford in 1972,65 combined with technology to create specific mAbs against cell surface differentiation antigens, finally provided the means to fractionate cells with high purity. As applied to stem cell fractionation, Visser et al were the first to use flow sorting based on wheat germ agglutinin binding as a means to enrich (6-fold) CFU-S compared with unfractionated bone marrow cells.66 Later it was possible to sort on the basis of cell cycle status using Hoechst dyes, and in this way CFU-S were distinguished from the more actively dividing granulocyte-macrophage-CFU progenitor cells.67 Improved cell fractionation based on cell surface markers and longer-term functional assays culminated in an important paper by Spangrude et al who purified mouse multipotential HSCs (although mostly those capable of relatively short-term repopulation) by combining depletion of several markers of maturation with expression of the Sca1 and c-Kit proteins (LSK cells).68 Improvements in markers and the use of single-cell transplantations have now resulted in essentially pure populations of HSCs capable of multipotential repopulation.40,69-72 However, only 20% to 50% of these clonal HSCs are capable of long-term repopulation; it remains unclear whether these HSC fractions are still not pure and that additional markers may be found to prospectively isolate HSCs with high capacity for self-renewal away from those with more limited capacity, or whether this remaining variability is because of stochastic influences on an otherwise pure HSC population.39,40 The intense efforts to purify murine HSCs and their downstream progeny established a pathway of discovery that could be applied to characterize human hematopoiesis.

Because studies of murine hematopoiesis showed that HSCs are distinct from CFU and that HSCs with short-term repopulation capacity are distinct from those with long-term capacity, it was clear that progress to understand human hematopoiesis would require a repopulation assay. The second key technologic development leading to the identification of LSC was the beginning of the modern era of the xenotransplantation system, which provided the key ability to functionally assay both normal stem cells and LSCs.73 Although there was a long history of transplanting human tumor cells into irradiated or immune-deficient nude mice, the strong host resistance in these mice allowed only the most aggressive tumors and cell lines to be engrafted. Primary human leukemia cells could not be transplanted and most cell lines only grew subcutaneously or as ascites, which was not a normal pattern for hematologic proliferation. In 1988, 3 groups using severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) or bg/nu/xid (BNX) mice, which are more immune-deficient than nude mice, showed that normal human hematopoietic cells could repopulate these mice. Mosier et al transplanted human peripheral blood leukocytes by intraperitoneal injection into SCID mice to enable long-term generation of mature T cells that could then be infected with HIV.74 McCune et al were also interested in developing an HIV model. They implanted SCID mice with pieces of human fetal liver, lymph node, and thymus,75 and later they injected human cells into fetal bone.76 The rationale of their approach was to provide a human tissue microenvironment that would continuously generate human T cells for HIV studies because the fetal liver (or fetal bone) would provide a source of stem cells. Of course, the long-term production of human cells within the fetal bone could be used to assay and identify HSCs, a premise that came to fruition when they showed that purified CD34+Thy+ cells could initiate multilineage engraftment of this bone fragment.77 Our approach was somewhat different and guided by the principles of bone marrow transplantation in humans and mice: intravenous transplantation into irradiated recipients resulting in human cells repopulating the hematopoietic tissues of a mouse.78-80 With improvements in recipient mice,81 it was finally possible to quantify and identify the cell that was capable of initiating a multilineage human graft, which was termed the SCID-repopulating cell (SRC).82-85 The SRC measured in this system generated many orders of magnitude higher cell numbers than the fetal bone in the SCID-hu model, providing a more robust method to detect only those cells with the highest repopulation capacity. Many improvements to the NOD/SCID assay continue to be made by using recipient mice that are engineered to be deficient in both NK and macrophage activity86,87 or that have been treated with a mAb to CD122 that depletes these components of the innate immune system.88-90 Recent studies that identified polymorphic alleles of Sirp-alpha governing human HSC engraftment in NOD/SCID mice establish the importance of controlling macrophages to achieve HSC engraftment.91 Finally, direct intrafemoral delivery of cells resulted in more sensitive SRC detection, as well as assessment of progenitors that possess transient repopulation potential, or are lineage restricted and would not read out in classic intravenous-based HSC transplantation assays.90,92-95

Characterization of normal human HSCs

The SRC xenotransplantation assay has emerged as the “gold standard” surrogate assay for human HSCs.96 Combined with clonogenic and stromal-based assays, it has been possible to identify many cell surface markers that define the developmental hierarchy of human hematopoiesis, setting the stage to apply these same markers to understanding leukemic hematopoiesis. A detailed understanding of the repopulation potential, cell-surface phenotype, differentiation, and proliferation properties of SRCs has been gained over the past 15 years.96,97 Most SRCs express CD34, and distinct SRC activities can be found within the lineage-negative (Lin−) CD34+CD38− and Lin−CD34+CD38lo subfractions.88,92,98-100

Personally, the culmination of our normal HSC studies was the use of lentivector-mediated clonal tracking101,102 to monitor greater than 600 clones in a cohort of primary and secondary mice for a total of 7 months.39 These studies touched on the longstanding debate on whether the control of cell fates is rigid and tightly organized or whether these outcomes are unpredictable and governed by stochastic processes. A single HSC can generate the entire blood system for a lifetime,40,69-72 a result that can only occur if at cell division the HSC self-renews to produce at least one daughter cell with the undifferentiated characteristics of the parental stem cell. Whether a hematopoietic clone is maintained or extinguished ultimately rests on whether an HSC makes an asymmetric (maintenance) or a symmetric self-renewing (expansion) or differentiating (extinction) division. These outcomes are known as the “birth and death” fates of stem cells.36 (see McKenzie et al39 for a more detailed discussion). We clonally analyzed hundreds of individual SRCs in primary and secondary mice; as well, we had the opportunity to analyze the repopulation properties of SRC daughter cells that became physically separated to different marrow locations within a single mouse.39 We found that the proliferation and self-renewal properties varied greatly. Even with increasing SRC purification, the variation in self-renewal capacity remained. Our results are reminiscent of the murine CFU-S data that were first reported approximately 45 years ago that formed the basis for the prediction that regulation of individual HSC outcomes is stochastic and governed by probabilistic elements.36 Our data provided experimental in vivo evidence (albeit with all the caveats of a xenotransplantation model) that is consistent with the hypothesis that human HSCs are also governed at least in part according to stochastic principles. Collectively, the identification and characterization of human HSCs set the stage for identification of their leukemic counterparts. The subsequent comparisons between normal and leukemic stem cells continue to provide clues to the cellular and molecular programs that drive their biology.

Identification of leukemia stem cells in AML

Because we were able to transplant normal human cells into mice, it was obvious that we should attempt to grow leukemic cells in mice. Our initial studies transplanting pediatric pre-B ALL into SCID mice showed the power of the system to propagate ALL with great similarity to the human disease103 and correlation to clinical outcome.104 Because we were interested in establishing whether normal HSCs could be assayed in SCID mice, this focus on thinking clonally impacted our leukemia studies. At this point, we turned our attention to AML because of the more extensive work on clonogenic assay systems and the application of stem cell concepts to understand this disease. I had been especially enamored by the clonogenic assay for AML progenitors and the studies from Buick and McCulloch, which showed that only a subset of AML-CFU had high serial replating efficiency, pointing to heterogeneity in self-renewal capacity.22,29,30 In parallel, the studies outlined in “Identification of normal HSCs in the mouse” clearly showed that normal clonogenic progenitors were distinct from repopulating HSCs, raising the question of whether the same would hold true for AML and that a more primitive LSC existed that was distinct from AML-CFU. The question was how to assay such a cell. As with any new line of investigation, collegial support was essential, especially from M. Minden and T. Hoang who provided primary AML samples and taught us how to properly thaw cells. We initiated experiments transplanting primary AML into SCID mice and obtained reliable engraftment from most subtypes of AML, except for APL. The subsequent critical experiments were performed with the prompting of my mentor R. A. Phillips who suggested we establish that the assay was quantitative by measuring the frequency of the initiating cell. This suggestion launched the application of stem cell principles to the study of the initiating cell in AML. Our first step was to establish the frequency of the initiating cell. Although we found it to vary by more than 1000-fold between donors, it was exceedingly rare: on the average of 1 per 106 cells. This was the first hint as to whether this initiating cell was actually distinct from the AML-CFU, which has a typical frequency of 1 in 100. Second, with the suggestion of my colleague N. Iscove, we carried out kinetic studies to show expansion of the AML-CFU pool during repopulation, as would be expected if they were being generated from an earlier precursor. Of course, it was possible that the initiating cell and the AML-CFU were the same cell if in vivo repopulation were simply an inefficient method to assay AML-CFU. Clearly, the only way to resolve this question was by fractionating the cells (ie, separating AML-CFU away from the initiating cells). CD34 was an obvious choice to fractionate with because expression on human HSCs had already been shown105 and adopted clinically for HSC enrichment. Prior work from Terstappen et al had pointed to CD34 and CD38 as being heterogeneously expressed in AML with the prediction that the various combinations of these 2 markers reflected a developmental hierarchy, with CD34+CD38− being the most primitive.106 The immediate obstacle was that I knew little about flow cytometry, and we did not have robust sorting capabilities in Toronto at that time. However, I had made the fortunate acquaintance of M. Caliguiri from Roswell Park who offered us access to their new highly modified beta test FACStar instrument run by C. Stewart. I have vivid memories of traveling with my postdoctoral fellow T. Lapidot (who deserves enormous credit for these studies) to Buffalo, sorting cells all day and racing back to Toronto to transplant the precious sorted cells into mice. I still recall with amusement the difficulties that the U.S. border agents had with his Hebrew Israeli passport. As others had seen, CD34 expression was highly variable in the AML samples we had evaluated and the one FAB-M2 sample we had used for sorting had greater than 40% CD34+ cells; however, CD38 was a smaller fraction of the CD34+ cells. AML-CFU activity was high in the CD38+ fraction compared with unsorted leukemia blasts but was also present in the CD38− fraction. Remarkably, despite the rarity of the CD34+CD38− fraction and the presence of high levels of AML-CFU in the CD34+CD38+ fraction, leukemic engraftment could only be initiated from CD34+CD38− fractions. In keeping with a tradition of naming cells based on function, we termed this the SCID leukemia-initiating cell (SL-IC). The CD34+CD38− SL-IC generated large numbers of CD34+CD38+cells, AML-CFU, and mature blasts. This was proof that the cell population that initiated AML in SCID mice was distinct from AML-CFU; we had identified a new stem cell in AML.107

Now is probably the best time to confess that I had no idea at the time that this experiment settled an even larger issue about the stochastic/hierarchy controversy, at least for AML. Not having read carefully all the literature I have outlined in this review, I did not realize that such a controversy existed because the hierarchy model was so well entrenched in the normal and leukemic hematopoiesis field; it was simply a given. In my view, all we had provided was the long sought after formal proof for the concept of a hierarchy in AML. There was one issue that concerned us. We had only tested a single sample in this initial study and it had a primitive FAB-M1 subtype and a high CD34 content. Perhaps the principle, or at least the CD34+CD38− phenotype, would not hold for AML, which exhibited a higher degree of cellular maturation, particularly the myelomonocytic M4/M5 subtypes. By this time, the new NOD/SCID mouse strain was found to be a superior recipient for normal HSC engraftment, permitting, for the first time, quantitative assessment and purification of normal HSCs.82-85 With this more robust assay, we studied in detail another 7 samples, 6 being M4 or M5. Many of these samples exhibited a distinct pattern of engraftment different from the primitive samples. The myelomonocytic samples disseminated widely, whereas the primitive subtypes typically grew well only in the bone marrow and only disseminated after long periods of time. Interestingly, although the M4 and M5 samples disseminated widely into many organs, they never infiltrated the central nervous system. This pattern was distinct from the pre-B ALL samples that we had studied earlier, which also disseminated widely but often infiltrated the central nervous system and the testis. These disease patterns that we observed in the NOD/SCID mouse reflected the clinical features of the disease in humans, pointing to the reliability of these new xenotransplantation models (compared with the older subcutaneous implantations in nude mice) to mimic the human disease. The cell purification data from these newer experiments were clear: despite their myelomonocytic morphology and their low CD34+ and CD34+CD38− populations, the LSCs were all found in the CD34+CD38− fraction.108 Although some exceptions were reported in subsequent years, a high proportion of AML patients show LSC activity in the CD34+CD38− fraction.109-111 As well, recent studies have suggested that the ability to engraft NOD/SCID mice112 as well as increased frequencies of LSC in AML are prognostic for poor outcomes.113 Collectively, these studies provide conclusive evidence for the hierarchy model in AML.

Cell of origin

When it came time to write the paper, D. Bonnet and I spent much effort reading the older literature, and we realized that our data could address the “cell of origin” question: what is the normal cell from which leukemia arises? Work from a number of directions, including the variation in cell surface marker expression on AML-CFU by Sabbath et al28 described earlier and the pioneering clonality studies in humans by Fialkow et al using X-linked G6PD polymorphisms114,115 followed by DNA-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis by Fearon et al,116 had been used to develop a theory that the maturation state of the leukemia blast reflected the level of maturation of the cell of origin.25 In vivo clonal studies in humans examined whether the normal nonleukemic lineages (lymphocyte, erythroid cell) were or were not part of the leukemic clone. Such an approach had definitively established that chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) arose in a multipotential HSC.117 If the nonleukemic cells were part of the clone, this reflected an early multipotential cell of origin, whereas if they were not part of the same clone, this reflected a more lineage-restricted cell of origin. This view was also proposed based on some of the earlier in vivo cytokinetic studies of Clarkson and others, albeit with less evidence than these clonal analyses could bring to bear. The alternative view, best articulated by McCulloch, was that observed lineage restriction was indeed only an apparent restriction and could not rule out the possibility that even the mature or lineage restricted AMLs arose from a multipotent HSC.22,29 He argued that transforming events could occur in an HSC, but one of the consequences of this event was an inability of this stem cell to generate other “normal” lineage cells, such as erythroid cells. As discussed in the following paragraph, we proposed that the similar cell surface phenotype of the LSC and the HSC supported the idea that primitive cells were the cell of origin for AML regardless of the maturation state of the leukemia blasts.108 Perhaps more than any other, this paper has caused confusion about the nomenclature of a “cancer stem cell,” especially when the CSC field exploded in 2003/2004 when solid tumor CSCs were identified.118,119 Our use of this nomenclature comes from the normal blood literature where cells are defined by function, in this case, the cancer cell that possesses stem cell properties. Our attempts to address the “cell of origin” question were taken by some to mean that a CSC was derived from a normal stem cell that had become cancerous. It finally took a blue-ribbon panel established by the American Association for Cancer Research to strongly declare that a CSC simply meant the cell in a cancer that has stem cell–like properties, especially the capacity for self-renewal.120

Although we made the argument that the cell of origin is primitive based on the consistency of the CD34+CD38− cell surface phenotype of SL-IC among patients regardless of AML subtype and their similarity to the phenotype of normal SRC, our reasoning had serious limitations. Cell surface markers are antigens whose expression changes with differentiation, and we know differentiation is perturbed in cancer. Therefore, one must be especially cautious when using a defined set of markers that rigidly reflect the steps of lineage determination of normal cells and then inferring that the same set will apply for neoplastic cells. Ideally, one would like to make comparisons between normal HSCs and LSCs using functional criteria. The only true stem cell property is capacity for maturation combined with self-renewal. In normal hematopoiesis, cell tracking and purification studies performed clonally (in mice and humans) have documented that long-term repopulating HSCs with high self-renewal capacity generate short-term HSCs whose self-renewal capacity is more limited.101,121 Thus, we carried out lentivector-mediated clonal tracking of AML-LSC in a manner identical to that outlined in “Characterization of normal human HSCs” for normal HSCs. These studies established that individual LSCs were not homogeneous but had wide variation in repopulation potential and self-renewal capacity similar to that observed for normal HSCs122 (Figure 3). However, a key difference is that, during NOD/SCID repopulation, LSCs expand to a much greater extent than normal HSCs, probably because of increased symmetric self-renewal cell divisions.108 As more information is gathered about the molecular machinery that underlies the self-renewal process, it is becoming clearer that LSCs and HSCs share at least some characteristics. For example, Bmi1123 and PTEN124 govern self-renewal of both murine HSCs and LSCs. Together with the findings that LSC can also be quiescent like normal HSCs,122,125-127 these discoveries add additional support to the notion that some types of AML may arise from within the primitive cell compartment, before full lineage commitment has occurred. Alternatively, it is also possible that AML could arise from committed progenitors if stem cell self-renewal programs are established during the leukemogenic process. Nevertheless, this evidence is still indirect and requires a more direct experimental approach.

Hierarchy of leukemia stem cells in AML. Like the normal hematopoietic system, AML is organized as a hierarchy of distinct cell classes that is sustained by a subset of leukemia stem cells (or SCID-leukemia initiating cells [SL-ICs], as assayed in immunodeficient mice). Genetic tracking experiments have shown that SL-ICs are heterogeneous in their ability to repopulate secondary and tertiary recipients, pointing to the existence of distinct classes with differing self-renewal capacity, similar to what is seen in the normal hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Short-term (ST) SL-ICs are able to initiate leukemia in primary but not secondary recipients, whereas long-term (LT) SL-ICs can sustain leukemic growth for multiple passages. Quiescent LT SL-ICs may not initiate a substantial graft in primary recipients and may therefore only be detected on serial transplantation.

Hierarchy of leukemia stem cells in AML. Like the normal hematopoietic system, AML is organized as a hierarchy of distinct cell classes that is sustained by a subset of leukemia stem cells (or SCID-leukemia initiating cells [SL-ICs], as assayed in immunodeficient mice). Genetic tracking experiments have shown that SL-ICs are heterogeneous in their ability to repopulate secondary and tertiary recipients, pointing to the existence of distinct classes with differing self-renewal capacity, similar to what is seen in the normal hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Short-term (ST) SL-ICs are able to initiate leukemia in primary but not secondary recipients, whereas long-term (LT) SL-ICs can sustain leukemic growth for multiple passages. Quiescent LT SL-ICs may not initiate a substantial graft in primary recipients and may therefore only be detected on serial transplantation.

The most direct experiment is to introduce the same genetic element into pure populations of HSCs or progenitor subsets to determine which population is competent to initiate disease. Attempts to identify the cell of origin for murine leukemia have yielded conflicting results, demonstrating that cellular and molecular context is critically important. The fusion oncogene MLL-GAS7 induces mixed-lineage leukemias when expressed in HSCs or multipotent progenitors, but not in lineage-restricted progenitors.128 In contrast, MOZ-TIF,129 MLL-AF9,130 and MLL-ENL131 lead to initiation of AML regardless of the target cell population used. However, much lower numbers of transformed HSCs compared with progenitors are often required for tumor initiation in vivo and tumors arising from progenitors are monoclonal or oligoclonal not polyclonal, suggesting that the progenitor populations were not functionally homogeneously, were not equally susceptible to transformation, or additional genetic alterations were required. Murine models of CML resulting from inactivation of JunB or expressing bcr/abl must occur in HSCs and not more restricted progenitors to induce a transplantable myeloproliferative disorder.129,132 These murine studies have become even more difficult to interpret with the recent findings of Chen et al who used a knockin model of MLL-AF9.133 This approach was taken because of concerns that, for some oncogenes, the level of expression from exogenous promoters, such as transgenes or retroviral vectors, may be nonphysiologic. They found that the same construct shown to initiate disease in HSCs and progenitors by retroviral expression only initiated leukemia from the HSC fraction when expressed from the endogenous MLL promoter. Nevertheless, collectively, these studies demonstrate that, under the correct circumstances and with the correct oncogene, it is possible to transform non-HSC in mice. The critical feature of these studies is that some component of an HSC or self-renewal program must be established in the non-HSC cell types.134

No direct studies of the design used for the murine studies have been reported for human hematopoietic cells. However, the in vivo clonality studies114,115 described earlier had pointed to variation in the cell of origin. A more refined approach was to examine whether phenotypically defined populations contained specific translocations and whether these exhibited normal or leukemic proliferation. A study of patients with t(8;21) AML demonstrated that, despite the presence of leukemia-specific AML1-ETO chimeric transcripts in primitive CD34+CD90−CD38− cells from leukemic bone marrow, these cells give rise to normally differentiating multilineage clonogenic progenitors, whereas more mature CD34+CD90−CD38+ cells form exclusively leukemic blast colonies (AML-CFC).135 Recent studies have documented that normal HSCs are CD34+CD90+CD38−, whereas the CD34+CD90−CD38− fraction represents a normal multipotential progenitor with little self-renewal capacity.136 Thus, a conclusion of this work is that, whereas the initial t(8;21) translocation occurs in a primitive stem cell, subsequent events occur in the committed progenitor pool, giving rise to LSCs. However, in vivo assays are required for formal proof that these are LSCs. A similar process of leukemic progression recently has been proposed for CML.137 The discovery of a marker chromosome,138 the nature of the translocation,139 followed by lineage involvement of the Ph chromosome,117 established that CML arose from an HSC; however, analysis of blast crisis samples suggests that additional genetic events occur at the level of more committed progenitors, resulting in the generation of LSCs.137 These provocative studies point to the need to understand not only the cell of origin of the LSCs but also the steps leading to so-called “preleukemic stem cells.”

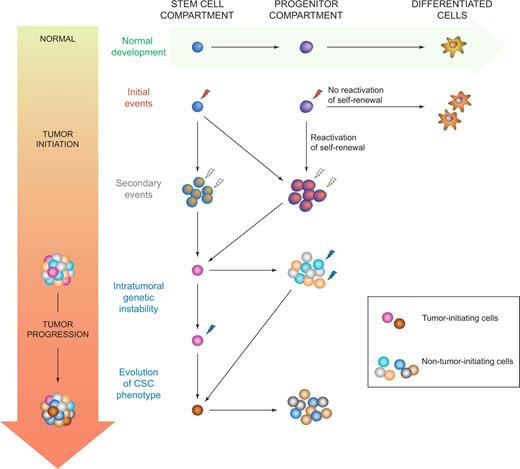

Our current understanding of the potential pathways leading to generating CSCs and a proposed model for tumor progression are depicted in Figure 4. Because the lifespan of non–stem cells may be transient, any genetic alteration in their makeup may not persist long enough to acquire additional genetic events that are needed for full transformation, unless the initial event endows the non-stem cell with self-renewal capacity. In addition, even when the stem cell sustains the first hit, subsequent events may occur in the stem cell or in the downstream progenitors. Another consideration is determining how the hierarchy model relates to leukemic progression or tumor evolution. Figure 4 proposes that tumor progression is linked to self-renewal capacity. For example, genetic instability and clonal evolution can occur in both CSCs and non-CSCs, keeping in mind that the rate of evolution could be different if CSCs proliferate more slowly than non-CSCs. Within the CSC fraction, additional genetic and epigenetic alterations could result in more abnormal CSCs; and in the case of solid tumors, these could become metastatic. The non-CSCs could also acquire genetic and epigenetic alterations; but if these do not endow self-renewal capacity, then these alterations in the non-CSCs are passengers and not drivers of tumor progression. Finally, if stem cell-like properties, including self-renewal, were endowed on non-CSCs, they could also drive tumor progression (Figure 4). A recent report has established in a breast cancer model that an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition program is linked to stem cell function and experimental induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in a non-CSCs can reprogram them to a CSC state, providing evidence for this tumor progression model.140

Models of tumor initiation and progression. Cancer stem cells may arise through neoplastic changes initiated in normal self-renewing stem cells or downstream progenitors, causing expansion of the stem cell and/or progenitor pool. Secondary events may occur in expanded pools of target cells. Oncogenic events acquired by short-lived progenitors may not persist if self-renewal is not reactivated, as these cells will probably die or undergo terminal differentiation before enough mutations occur for full neoplastic transformation. Tumor progression may be linked to ongoing genetic instability and acquisition of additional changes by cancer stem cells, or possibly by nontumorigenic bulk cells if such changes endow self-renewal. In both cases, evolution of tumor phenotype (including genetic and epigenetic signatures) may be observed.

Models of tumor initiation and progression. Cancer stem cells may arise through neoplastic changes initiated in normal self-renewing stem cells or downstream progenitors, causing expansion of the stem cell and/or progenitor pool. Secondary events may occur in expanded pools of target cells. Oncogenic events acquired by short-lived progenitors may not persist if self-renewal is not reactivated, as these cells will probably die or undergo terminal differentiation before enough mutations occur for full neoplastic transformation. Tumor progression may be linked to ongoing genetic instability and acquisition of additional changes by cancer stem cells, or possibly by nontumorigenic bulk cells if such changes endow self-renewal. In both cases, evolution of tumor phenotype (including genetic and epigenetic signatures) may be observed.

Modeling the human leukemogenic process

A major limitation in understanding the leukemogenic process in humans is the absence of good genetic tools and experimental models that use primary human cells as their starting point. For example, the first step to directly test the cell of origin hypothesis requires an experimental model of human leukemogenesis where oncogenes are transduced into primary human hematopoietic cells. Several reports have demonstrated that the initial steps in the leukemogenic process could be induced experimentally by expression of several different oncogenes, such as Ras,141 TLS-ERG,142,143 AML-ETO,144 and bcr/abl,145 but none caused full-blown disease (see Kennedy and Barabé146 for detailed review of human leukemogenesis studies). Using MLL fusions, 2 recent studies have demonstrated successful induction of AML and pre-B ALL in NOD/SCID transplanted with transduced primary stem/progenitor cells.147,148 These mice developed B-ALL and AML that reflected the human disease. We found that the B-ALL in this model maintained a germ line configuration of the IgH locus early in disease evolution but progressed to full rearrangement on serial passage.147 These data suggest that the LSC can evolve and that the cell of origin was not a mature B cell, but a more primitive stem or progenitor cell. Direct elucidation of the cell of origin will require prospective cell sorting of pure, functionally defined HSCs, and progenitor subsets as targets for testing.

Although the NOD/SCID studies were compelling, direct evidence for LSC evolution in humans was lacking. In a seminal series of studies beginning in the 1990s, Greaves and Wiemels demonstrated that many forms of childhood leukemia arose in utero.149 They studied twins in which one twin has leukemia whereas the other does not; both were shown to contain the same chromosomal translocations (MLL, Tel-AML1), a result that could only occur if a single cell in one twin acquired the translocation, expanded, and migrated to the other twin. By examination of Ig rearrangements, they concluded that after birth additional genetic alterations occur independently in each twin, resulting in the appearance of leukemia at different times. This predicts that the twin who has not yet developed leukemia must contain a preleukemic stem cell that is poised to acquire additional alterations because this twin is at high risk of developing leukemia. In an elegant series of studies, Hong et al have identified a unique cell population, not observed in normal donors, that contains a preleukemic stem cell that exhibited enhanced self-renewal capacity when assessed in the NOD/SCID xenotransplantation system.150 This preleukemic population was clonally related to the LSC that maintained the leukemia in the affected twin. Thus, this study provides strong proof in humans for the concept of clonal evolution of LSC from a preleukemic to a leukemic state.

Controversies

Recently, several reports were published that questioned the universality of the CSC or hierarchy model.151,152 Several experimentally induced murine leukemia models were found where almost every cancer cell had LSC activity and there was little evidence of functional heterogeneity. These and other reports153 speculated that the rarity of human CSCs observed using xenotransplantation models may be the result of host resistance factors as well as the absence of cross-species reactivity of cytokines and other microenvironmental factors. Certainly, such factors play a role because the use of more immune-deficient mice has improved human CSC detection; in addition, some solid tumor studies are now using coimplantation of human stromal cells. It is important to note that a number of other genetically induced murine leukemia models are heterogeneous and contain discrete and rare LSCs.154 Moreover, when human and murine leukemia models were both induced with the same MLL fusion protein, the LSC frequency was the same.154 Thus, it is evident that LSC frequencies can vary widely among different cancers regardless of whether they are quantified using xeno- or syngeneic transplantation assays. It is important to emphasize that the fundamental concept underlying the CSC model is not directly related to the absolute frequency of these cells but rather on functional evidence of tumor heterogeneity and a hierarchical organization. The CSC model is only invoked to explain tumor heterogeneity; however, if a tumor is functionally homogeneous, the CSC model is no longer relevant. It is clear that some murine cancer models do not follow the hierarchy model, and it will be important to survey a much broader cross section of human tumors to determine whether any also lack tumor heterogeneity.

The future of CSC research

Despite the recent explosion of interest in CSCs, experimental studies have not been translated into improved survival outcomes for cancer patients. This presents a major question to the field: do cancer stem cells have meaningful relevance beyond the experimental systems in which they have been defined? Increasing evidence is pointing to CSCs having unique biologic properties (dormancy, drug/radiation resistance) that could permit them to survive therapies leading to eventual relapse. To date, CSCs have been studied in a relatively small number of patient samples and cancer types, so it is not known whether the CSC model is universal to all human cancers.1 The biologic relevance of CSCs in human cancer will be established by concentrating on the following research endeavors: improving the assay and purification of CSC and non-CSC subsets, carrying out detailed genomic or proteomic analysis on these subsets to identify CSC-specific signatures, and obtaining such signatures from a large number and wide range of tumors. Such an approach would make it possible to determine whether the “omics” of CSCs provide more predictive or prognostic relevance compared with analysis of the bulk tumor. An approach like this has recently been taken by Liu et al who showed that a breast CSC signature has improved correlation to patient outcomes.155 Of course, the most direct proof for the relevance of CSCs to cancer would be to use the CSC-specific signatures to elucidate the key molecular pathways involved, develop the means to target them effectively, and establish in clinical trials whether targeting them enhances patient survival.

For many types of leukemia, the long-term survival has increased dramatically over the past 50 years; however, AML remains one of the most difficult diseases to cure. The majority of patients will die because of relapse, drug resistance, or from complications associated with chemotherapies. Because LSCs and HSCs have many similar properties, a first step to develop novel therapies has been to identify unique properties that LSCs possess. Through expression analysis, Guzman et al determined that the NF-κB pathway was active in LSCs and not in HSCs.126 They then went on to identify a natural product, parthenolide, which targets this pathway and showed that the LSCs could be specifically targeted using the NOD/SCID model.156,157 It should be possible to develop a strategy that focuses on the biology of LSC and develop assay methods that are compatible with high throughput screening of small molecule libraries followed by counterscreens with normal HSCs or progenitors.158 Other approaches focus on identification of differences in cell surface markers with concomitant development of immunoconjugates with toxic moieties. LSCs could be targeted with a diphtheria toxin conjugated to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor immunotoxin.159,160 However, not all AML samples responded to these molecules, and regrowth or unsuccessful eradication of the leukemic cells occurred after different treatment strategies, suggesting that not all classes of SL-IC were killed by diphtheria toxin conjugated to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor immunotoxin. Similarly a DT-IL3 conjugate was shown to target the LSC and progressed to clinical trials. Unfortunately, this therapy resulted in the development of antibodies as well as other toxicities.161 As well, LSCs could be targeted with a CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte clone specific for minor histocompatibility antigens,162,163 an approach that might be useful in the context of AML patients who undergo allogeneic transplant and then relapse. More recently, several studies reported that LSCs could be targeted with mAb to CD44164 or CXCR4.165 When these mAbs were injected into NOD/SCID mice repopulated with AML, the LSCs were markedly depleted; and in some cases, the mice were cured. Induction of differentiation represented a partial mechanism of action. Even more noteworthy, both CXCR4 and CD44 resulted in impaired trafficking of the LSC, suggesting that LSCs remain dependent on niche interactions. Because many other factors are involved in trafficking and homing (see 50th Anniversary Review by Papayannopoulou and Scadden166 ), this finding opens the way for testing the anti-LSC functionality of any molecule that interferes with these processes. Little is known of the LSC niche; however, a recent study points to the endosteal region,167 an area that has been proposed as the niche for murine HSCs as well. Another LSC-specific target, which is either low or absent from normal HSCs, is CD123, the alpha chain of the IL3R.168 A mAb targeting CD123 impairing homing of LSC to bone marrow of NOD/SCID mice, and it activates the innate immunity of NOD/SCID mice resulting in eradication of LSCs.169 Collectively, these studies provide clear validation for therapeutic mAb targeting of AML-LSCs and for translation of the NOD/SCID in vivo preclinical research findings toward a clinical application. Finally, future therapeutic approaches will need to be developed that target the self-renewal machinery of LSCs, although it may be difficult to find a therapeutic window that will spare normal tissue stem cells. As predicted from the cytokinetic studies, perhaps the most attractive option is to induce the quiescent LSCs into cycle. Recent studies are pointing to specific molecular pathways that might be attractive, including PTEN, p21, and PML. Ito et al have found that degradation of PML induces cycling of LSC and, interestingly, that one of the mechanisms of action of arsenic is degradation of PML, already putting a potential drug strategy in hand.170

Although this review is focused on the premise that improvements in the stubbornly high relapse rates for many cancers will come from more research on the CSCs that drive the tumors, attention is needed on how to move CSC therapies into clinical trials and into the clinic (a more thorough discussion is done by Wang171 ). The current approaches to preclinical drug development and clinical evaluation of drug efficacy focus on initial requirements for tumor response. Therefore, a potentially effective anti-CSC therapy might be discarded from further testing if it does not cause a response of the non-CSCs cells rapidly enough. Similarly, an effective anti-CSC might take time to show efficacy or be most effective in an adjuvant setting. Much research effort will be required to find the best algorithms for clinical evaluation of CSC-targeted therapies.

In conclusion, stem cell concepts lie at the heart of the first cancer therapies developed almost 40 years ago, which showed the first tangible success in curing patients with acute leukemia. One hopes that the renewal of interest in the linkage between stem cells and cancer will lead to a better understanding of how the cellular context of tumors affects cancer-specific genetic and epigenetic pathways and will once again drive new therapeutic advances.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Dick laboratory members, Jean Wang, Bob Phillips, Norman Iscove, Tsvee Lapidot, and Mark Minden for advice and comments; Barney Clarkson for discussions and for sharing a treasure trove of “hard-to-find” papers; Jean Wang for creating the figures; and Melissa Cooper for insightful editing.

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and a Summit Award both with funds from the Province of Ontario, Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute, the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, and the National Cancer Institute of Canada with funds from the Canadian Cancer Society and the Terry Fox Foundation, research contracts with CSL and Arius, and a Canada Research Chair.

Authorship

Contribution: J.E.D. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares research contracts with CSL and Arius.

Correspondence: John E. Dick, Toronto Medical Discovery Tower, 101 College Street, Room 8-301, Toronto, ON, Canada M5G 1L7; e-mail: jdick@uhnres.utoronto.ca.

![Figure 3. Hierarchy of leukemia stem cells in AML. Like the normal hematopoietic system, AML is organized as a hierarchy of distinct cell classes that is sustained by a subset of leukemia stem cells (or SCID-leukemia initiating cells [SL-ICs], as assayed in immunodeficient mice). Genetic tracking experiments have shown that SL-ICs are heterogeneous in their ability to repopulate secondary and tertiary recipients, pointing to the existence of distinct classes with differing self-renewal capacity, similar to what is seen in the normal hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Short-term (ST) SL-ICs are able to initiate leukemia in primary but not secondary recipients, whereas long-term (LT) SL-ICs can sustain leukemic growth for multiple passages. Quiescent LT SL-ICs may not initiate a substantial graft in primary recipients and may therefore only be detected on serial transplantation.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/112/13/10.1182_blood-2008-08-077941/4/m_zh80230827340003.jpeg?Expires=1763639125&Signature=hulirSukfnmtL~LWaqIVIMX~WWt4R3T-EK35nj56hOpjWeys22ttS8J7R5ouzD4XsjbXcdwMA8Ky80X-kqH-bzW7n5o7BzNgozdbrXS~-rONNi0w5p~QaOJOSRw9ctSMJdWJn-mE-EaFDMwIYvev4jHCNNtnqlN9PwmqdHxQsEmhwVoVs6ltChlg8bk-OTd8Je35Ls1n~Qvl~dgkxkZdHoKnc3BEwXbWdM3sMgPgKhGBE5T8Fr~6ELFzpKbHJu0mF-emKX3abocTzJmDsux4idd4lYnxuTZ2XARluySljRK9vVxIS533Jh8zuJVI0BC0NE08tS0hJR0anmUjy4VPKw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Hierarchy of leukemia stem cells in AML. Like the normal hematopoietic system, AML is organized as a hierarchy of distinct cell classes that is sustained by a subset of leukemia stem cells (or SCID-leukemia initiating cells [SL-ICs], as assayed in immunodeficient mice). Genetic tracking experiments have shown that SL-ICs are heterogeneous in their ability to repopulate secondary and tertiary recipients, pointing to the existence of distinct classes with differing self-renewal capacity, similar to what is seen in the normal hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Short-term (ST) SL-ICs are able to initiate leukemia in primary but not secondary recipients, whereas long-term (LT) SL-ICs can sustain leukemic growth for multiple passages. Quiescent LT SL-ICs may not initiate a substantial graft in primary recipients and may therefore only be detected on serial transplantation.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/112/13/10.1182_blood-2008-08-077941/4/m_zh80230827340003.jpeg?Expires=1764057232&Signature=vA6JkD7TcrqdJ97dctWSZyQk4AY0mtViiWNlkpssIzxtTJKQHY-LteZ69K~sKYgbEpr11szpPch~iYK51pY7i5F9X8s4NppoqLK31oqgsmbODWCJ~bXtXWyJMkXeeI-fBF8qbm-106Kjs-nOs7rE7CR33pTpbrooV9ofxHINR3kgiqBzeyBbsOsBeRABn3T-~VQD6secyyTAt3WoVGIj3FlnT2ypUsdFQEDv3mhW~6l8qXvzKaiFwXQsP~pLjDQWLz1AqB3A2cFpKXNXPPZ8kKw~JN6B7yRx1af2N~MQKeJb4YrQtCsspoHtOi8HVhF0kUFjyckBI3mElAdGOVamqg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)