In the present study, we evaluated whether infection of microvascular endothelial cells (HMECs) with HHV-8 can trigger the expression of PAX2 oncogene and whether PAX2 protein is involved in HHV-8–induced transformation of HMECs. We found that HHV-8 infection induced the expression of both the PAX2 gene and PAX2 protein in HMECs but failed to induce PAX2 protein in HMECs stably transfected with PAX2 antisense (HMEC-AS). HHV-8–infected HMECs but not HMEC-AS acquired proinvasive proadhesive properties, enhanced survival and in vitro angiogenesis, suggesting a correlation between PAX2 expression and the effects triggered by HHV-8 infection. When HMEC-expressing PAX2 by stable transfection with PAX2 sense gene or by HHV-8 infection were implanted in vivo in severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice, enhanced angiogenesis and proliferative lesions resembling KS were observed. HHV-8–infected HMEC-AS failed to induce angiogenesis and KS-like lesions. These results suggest that the expression of PAX2 is required for the proangiogenic and proinvasive changes induced by HHV-8 infection in HMECs. In conclusion, HHV-8 infection may activate an embryonic angiogenic program in HMECs by inducing the expression of PAX2 oncogene.

Introduction

HHV-8, also know as Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV), is a gamma-herpesvirus initially identified by Chang et al in 1994 from a Kaposi sarcoma (KS) biopsy.1 HHV-8 is considered the primary etiologic agent of KS, a highly vascularized neoplasm characterized by the presence of spindle-shaped cells, angiogenesis, and inflammatory infiltrates. HHV-8 is also implicated in other 2 AIDS-associated malignancies: the primary effusion lymphoma2 and the multicentric Castleman's disease.3 HHV-8 infection is frequently associated with immunodeficiency related to HIV-1 or to immunosuppression.4

The viral genome of HHV-8 contains several genes that are homologous to proto-oncogenes capable of inducing malignant tumors.5,6 It has been suggested that KS spindle-shaped cells may origin from vascular endothelial precursor cells infected with HHV-8 that induces in these cells spindle morphology and increases the life span and proliferation.7,8

Recently, we demonstrated that the expression of PAX2 by KS cells correlated with an enhanced resistance to apoptotic signals and with a proinvasive phenotype.9

The PAX2 gene belongs to a family of 9 homeobox genes10,11 that bind to DNA to initiate transcription of specific genes. Its expression is restricted to embryogenesis and is down-regulated in adults to be reexpressed in several tumors.12,–14 Indeed, a pro-oncogenic potential has been ascribed to the PAX gene family15,16 ; indeed, several chromosomal translocations involving members of the PAX genes family have been described in various human cancers, suggesting that altered regulation of PAX gene products can promote cellular transformation.17,–19 In particular, the inappropriate expression of PAX2 has been identified in Wilm tumor,18 renal cell carcinoma,20 breast cancer,21 prostate cancer,22 and KS.9

Recently, we demonstrated that transfection of HMECs with PAX2 cDNA induced spindle shape morphology, enhanced motility, and survival.9,23 These data suggest the involvement of PAX2 in the possible origin of KS cells from endothelium.

In the present study, we evaluated whether the infection of HMECs with HHV-8 can trigger the expression of PAX2. In addition, we studied whether the expression of PAX2 by HHV-8–infected HMECs is instrumental in conferring to HMECs angiogenic and invasive properties. To this purpose, we transfected HMECs with an antisense vector of PAX2 (HMEC-AS) to inhibit the synthesis of PAX2 protein triggered by HHV-8.

Methods

Cell lines

HMECs were obtained from derma or from normal renal tissue (r-HMECs) using anti-CD31 antibody coupled to magnetic beads, by magnetic cell sorting (MACS System; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). HMECs from derma were immortalized by infection of primary cultures with a replication-defective adeno-5/SV40 virus as previously described.24 The previously characterized renal carcinoma cell line K1, obtained from a renal clear cell carcinoma, was maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS).25

Cloning of PAX2 gene

Cloning of the PAX2 gene was performed as previously described.9 Briefly, 2 μg RNA was reverse-transcribed using oligo(dT) primers and 15 U reverse transcriptase enzyme (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany); 5 μL cDNA was amplified with forward and reverse primers (forward, 5′-ATGGATATGCACTGCAAAGCAGA-3′; reverse, 5′-CTAGTGGCGGTCATAGGCAG-3′) covering the initial and terminal part of the coding sequence, respectively (NCBI GenBank no. GI409138),23 with TaqDNA polymerase (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Amplified DNA was ligated with the T/A cloning system into pTARGET mammalian expression vector (Promega, Madison, WI) for expression under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter. We identified a clone with PAX2 in correct orientation (S) and a clone with PAX2 in inverse orientation (AS). DNA sequences were compared with the NCBI database using the BLAST program.

Transfection

HMECs were seeded in a T25 flask to reach confluence and transfected with 8 μg DNA and 20 μL LipofectAMINE 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium plus 10% FCS without antibiotics, according to the protocol suggested by the manufacturer. As a control, cells were transfected with empty plasmid. Transfected cells were stably selected by culturing in the presence of 1 mg/mL geneticin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Successful transfection was evaluated by immunofluorescence and Western blotting. HMECs were stably transfected up to passage 10. To verify that transfection did not impair the behavior of endothelial cells, a proliferation assay was performed and DNA synthesis was detected as incorporation of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine into the cellular DNA using an enzyme-linked immunoadsorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA).23

HMEC infection with HHV-8

The cell-free HHV-8 inoculum was obtained by stimulation of BC-3 cells with 20 ng/mL of TPA (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 days, as previously described.26

All cell-free virus preparations contained approximately 4.7 × 105 copies of viral DNA per microliter, as quantified by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as previously described. For virus infection, HMECs were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates. After 24 hours, cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and infected with 10 μL/mL per well of purified virus preparation. After 3 hours of absorption at 37°C, the viral inoculum was removed, and cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated in fresh medium. Cells and culture supernatants were harvested at specific time points for subsequent analysis by PCR and reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions; 2 μg RNA was reverse-transcribed using oligo(dT) primers and 15 U reverse transcriptase enzyme (Eppendorf); 2 μL cDNA was amplified with PAX2 forward (5′-ATGGATATGCACTGCAAAGCAGA-3′) and reverse (5′-CTAGTGGCGGTCATAGGCAG-3′) primers and TaqDNA polymerase (Invitrogen). Reactions were performed for 30 cycles at a melting temperature of 52°C and analyzed with an ethidium bromide 1.5% agarose gel. The presence and the level of transcription of HHV-8 in HMECs were analyzed by PCR and RT-PCR amplification of the following genes: ORF26, ORF50, ORF73 (LANA), and ORF74 (vGPCR). PCR amplification was performed using, respectively 100 ng total DNA or 200 ng total RNA extracted from infected cells, with specific primers and PCR conditions as previously described.26 Amplification of the housekeeping β-actin gene was used as a control. PCR was also used to detect newly released virus particles in the supernatant of infected cells at different times productively infected. In this case, the presence of viral DNA was determined by analyzing ORF50 levels after sample pretreatment with DNAse to exclude contamination by free unencapsidated viral DNA. The absence of the β-actin gene in the same samples excluded that positive signals could be the result of the presence of DNA released from lysed cells. For the relative quantitation of PAX2 mRNA by real-time PCR, 1 μg total RNA was retrotranscribed with high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in 20 μL reaction. Relative quantitation by real-time PCR was carried out using SYBR-green detection of PCR products using Step ONE Detection System (Applied Biosystems); 10 ng cDNA for each tube reaction was subjected to amplification using 100 nM primers for β2-microglobulin as housekeeping gene (for 5′-AGATGAGTATGCCTGCCGTGT-3′; rev 5′-GCTTACATGTCTCGATCCCACTTA-3′) and 100 nM primers for PAX2 gene (for 5′-CCCAGCGTCTCTTCCATCA-3′; rev 5′- GGCGTTGGGTGGAAAGG-3′) in a 20-μL reaction using 2× SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The relative expression of different mRNAs was determined by relative quantification: δCt = Ct target − Ct β2-microglobulin, where β2-microglobulin represents the reference housekeeping gene. The target quantity is given by x target =2− δCt. Each sample was processed in triplicate.

Immunofluorescence

Cells, fixed in methanol/acetone (ratio 1:2) for 10 minutes at −20°C, were incubated either with the anti-PAX2 (Covance Research Products, Princeton, NJ) polyclonal antibody or with anti-ORF K8.1A (Advanced Biotechnologies, Columbia, MD) monoclonal antibody, followed by FITC-conjugated antirabbit and by phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated antimouse antibodies.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed for detection of PAX2, Akt, and P-Akt as previously described.9,25 The following antibodies were used: anti-PAX2 polyclonal antibody (Covance), anti-Akt1 IgG1 monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti–P-Akt (Cell Signaling Technology) and anti–β-actin polyclonal antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Adhesion assay

Cells were cultured to confluence in gelatin-coated 24-well tissue culture plates. Before the assay, the monolayers were starved in RPMI plus 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Mononuclear cell fraction of peripheral blood samples of healthy donors was separated on 1077 Ficoll-Hypaque (Nyegaard, Oslo, Norway) density gradient. Leukocytes obtained were labeled with the intravital red fluorescent cell linker PKH26 (Sigma-Aldrich) and added to the endothelial monolayers at the density of 5 × 105 cells. The adhesion assay was allowed to proceed for 30 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2, in a humidified atmosphere in static conditions. The plates were then washed 3 times with PBS to remove the unattached cells. In some experiments, endothelial monolayers were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2, in a humidified atmosphere, with anti-ICAM-1 blocking antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany). Each experiment was done in triplicate. Labeled cells attached to the endothelial monolayer were counted in 5 fields (magnification ×100) by fluorescence microscopy and expressed as number cells/microscopic field.

Fluorescent-activated cell sorter analysis

The expression of surface markers on HHV-8-infected HMECs and HMEC-AS was evaluated by cytofluorimetric analysis and was compared with control HMECs. Anti–ICAM-1 mouse antihuman monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was used as primary antibody. Cells were detached using EDTA 0.05 M and incubated with 1% BSA in PBS to block nonspecific sites. Cells (2 × 106) were then incubated with the specific antibody for 30 minutes and finally with PE goat anti–mouse IgG for 20 minutes. The analysis was performed using a FACSCalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences). At least 10 000 events were acquired for each analysis. The analysis was performed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Matrigel invasion assay

Invasion ability was evaluated using Transwell chambers (Costar, Cambridge, MA), in which the upper and the lower chambers were separated by 8-μm pore size polyvinylpyrrolidone-free polycarbonate filters. Briefly, before the invasion assay, filters were coated with 100 μg/well Matrigel (BD Biosciences) diluted in culture medium. The lower compartment was loaded with medium plus 10% FCS. HHV-8-infected cells (5 × 104 cells/well) were seeded onto the upper compartment and were incubated for 48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2, in a humidified atmosphere. Cells migrated to the underside of the filters were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa solution (Diff-Quik kit; Harleco, Gibbstown, NJ), counted in 5 fields (magnification 100×) in each well by light microscopy, and expressed as number of cells/microscopic field. Each experiment was done in triplicate.

Zymographic analysis

Gelatinolytic activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) were assessed under nonreducing conditions using a modified SDS-PAGE. HHV-8–infected and uninfected cells were starved overnight. Aliquots of supernatants for each cell line were mixed with Laemmli buffer and applied onto an 8% polyacrylamide gel copolymerized with 1 mg/mL gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich). Electrophoresis was done under constant voltage (150 V) for 2 hours. The gel was washed 3 times for 20 minutes each time with 2.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) to remove SDS and to allow the electrophoresed enzymes to renature before incubation in zymography buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.06% Brij 35 solution 30% pH 7.5) for 48 hours at 37°C. The gel was then stained with 0.5% Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1:3:6 acetic acid/methanol/water for 15 minutes and destained with 1:3:6 acetic acid/methanol/water. An aliquot of RPMI containing 1% of serum was used to determine the molecular weight of the gelatinase. The clear bands represented gelatinase activity. To determine whether zones of lysis detected by zymography were produced by MMPs, one gel was incubated with zymography buffer in the presence of 5 mM EDTA.

Cell motility

A total of 105 cells/well were plated in RPMI plus 5% FCS. Cell motility was studied over a 4-hour period under a Nikon Diaphot inverted microscope with a 20× phase-contrast objective in an attached, hermetically sealed Plexiglas Nikon NP-2 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) incubator at 37°C, with a MicroImage analysis system (Cast Imaging, Venice, Italy) and an IBM-compatible system equipped with a video card (Targa 2000, Truevision, Santa Clara, CA). Image analysis was performed by digital saving of images at 15-minute intervals. Migration tracks were generated by marking the positions of the nuclei of individual cells on each image. The net migratory speed (velocity straight line) was calculated by the MicroImage software based on the straight line distance between the starting and ending points divided by the time of observation.27 Migration of at least 30 cells was analyzed for each experimental condition. Values are given as means plus or minus SD.

ELISA

For analysis of MCP-1 production, supernatants from HHV-8-infected or uninfected HMECs were collected at different productively infected times, cleared by centrifugation to eliminate cell debris, and stored at −80°C. After thawing, samples were analyzed in triplicate for the presence of MCP-1 using a specific quantitative ELISA kits (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA).

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was evaluated using the terminal deoxynucleotide transferase–mediated dUTP-biotin nick end-labeling assay (ApoTag Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions as previously described.23

In vitro angiogenesis assay

The assay was performed as previously described.23 Briefly, 24-well plates were coated with growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences) at 4°C and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2, in a humidified atmosphere. HHV-8–infected and uninfected cells were seeded on the Matrigel-coated wells in RPMI plus 5% FCS at the density of 5 × 104 cells/well. After a 6-hour or 24-hour incubation, cells were observed with a Nikon inverted microscope (Nikon), and the experimental results were recorded. The extent of capillary-like structures was measured with the MicroImage analysis system (Cast Imaging) and expressed in arbitrary units. Experiments were performed also in the presence of 1 μg/mL of anti-MCP-1 antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

In vivo angiogenesis assay

For the in vivo studies, an in vivo Matrigel angiogenesis assay was performed, in which cells were subcutaneously injected into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice (Charles River, Calco, Italy; n = 5 for each experimental condition) as previously described.23 Briefly, cells were harvested using trypsin solution (Sigma-Aldrich), washed with PBS, resuspended in 250 μL Dulbecco modified Eagle medium, and added to 250 μL of growth factor–reduced Matrigel at 4°C. Cells were injected subcutaneously into the mid-abdominal region of SCID mice via a 26-gauge needle and a 1-mL syringe. At day 6, mice were killed, and the plugs were recovered and processed for histology. The vessel's area was planimetrically assessed using the MicroImage analysis system (Casti Imaging). The human nature of endothelial cells was assessed by immunofluorescence with an anti-HLA class I polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and human anti-CD31 (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Results

HHV-8 infection in HMEC

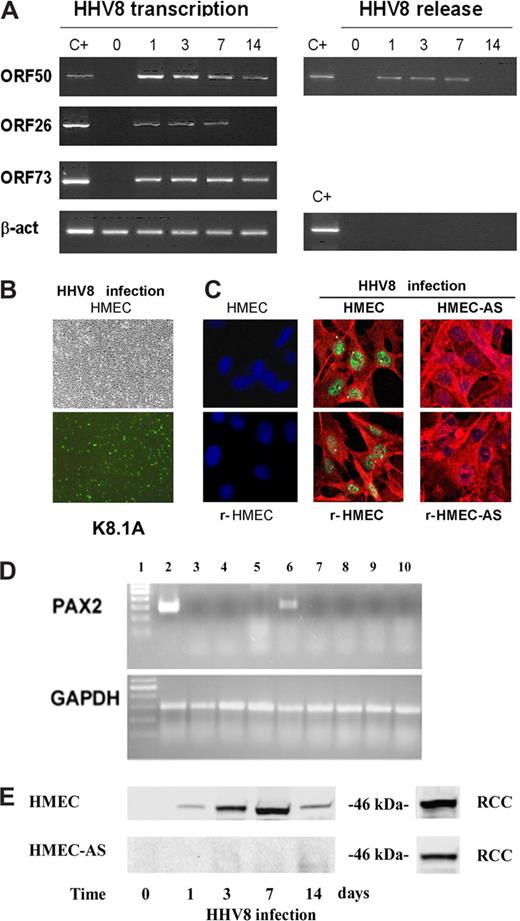

HMECs were infected with a cell-free virus inoculum obtained by gradient purification of viral particles produced in TPA-induced BC-3 cells. HMEC monolayers were infected with virus suspension for 3 hours at 37°C. After the absorption period, the inoculum was removed, the monolayer was washed, and fresh medium was added to the cells. HHV-8 infected cells developed the characteristic spindle cell morphology. Infection with HHV-8 was verified by PCR and RT-PCR detection of immediate-early, late, and latent viral genes (ORF50, ORF26, and ORF73, respectively). The results, summarized in Figure 1A, show that HHV-8 caused a productive infection that lasted for 7 days, as shown by the expression of ORF50 and ORF26 lytic genes. Approximately 20% of cells were productively infected (1 day), as judged by the number of cells positive for the presence of HHV-8 lytic antigen K8.1 in IFA (Figure 1B) and by real-time PCR results to quantitate the number of HHV-8 genomes inside infected cells (data not shown). No cytopathic effect and no virus-induced cell lysis were observed. The number of infected cells increased over time, reaching 40% 3 days productively infected, and 60% to 80% 7 days productively infected, taking into account both lytic and latent antigens. Lytic antigens were prevalent 3 days productively infected, and latent antigens were predominant 7 days productively infected. The occurrence of productive infection in HMECs was confirmed by detection of newborn virus released in the culture supernatants as determined by PCR. Virus DNA was detectable in culture supernatants 1, 3, and 7 days after infection. The PCR-positive signal could not be ascribed to residual virus inoculum (time 0 shows supernatants after absorption and washes), nor to the release of viral DNA from infected cells. Indeed, supernatants were DNAse treated and were PCR negative before DNA extraction (data not shown). After day 7 of infection, the virus entered the latent phase, as shown by the disappearance of ORF26 lytic transcript, and the absence of virus in the cultures supernatant (Figure 1A).

HHV-8–induced acute infection and PAX2 expression in HMECs. (A) Subconfluent HMEC monolayers were infected with HHV-8 and analyzed at different productively infected times for virus transcription and release. RT-PCR amplification was performed for the indicated HHV-8 genes using RNA extracted from infected cells. β-actin levels were determined in the same samples as control. Positive controls of amplification of the genes analyzed (C+) are shown. Virus release was evaluated in the culture supernatant by PCR amplification of HHV-8 ORF50 gene. β-actin gene was also amplified to verify the absence of cellular contaminating DNA. (B) Representative micrographs of the same microscopic field observed by phase contrast and by immunofluorescence showing that approximately 20% of the cells stained for the viral HHV-8 antigen ORF K8.1A. Micrographs were obtained by Zeiss Axioskop (Jena, Germany) using 20× objective. (C) Representative confocal micrographs costaining of PAX2 (green) and the viral HHV-8 antigen ORF K8.1A (red) in control uninfected dermal HMECs and renal-HMECs (r-HMECs) and, in HHV-8–infected HMECs, r-HMECs, HMEC-AS, and r-HMEC-AS. Uninfected HMECs and r-HMECs did not express PAX2, but 3 days after infection they showed nuclear staining for PAX2. HHV-8 infection failed to induce PAX2 expression in HMEC-AS and r-HMEC-AS (Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a helium/neon 543 mm laser, an argon 450 to 530 mm laser, and an EC planar NEOFluar 40×/1.3 oil DIC objective lens; acquisition software, Zeiss LSMS, version 3.2). (D) Representative RT-PCR showing the expression of PAX2 mRNA in cells derived from renal carcinoma used as positive control (lane 2), in HMECs infected with HHV-8 after 8 hours (lane 3), 16 hours (lane 4), 24 hours (lane 5), and 3 days (lane 6) and in HMEC-AS infected with HHV-8 after 8 hours (lane 7), 16 hours (lane 8), 24 hours (lane 9), and 3 days (lane 10). (E) Representative Western blot analysis of PAX2 protein expression by HMECs and HMEC-AS after 8 hours, 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after HHV-8 infection showing a band corresponding to 46 kDa. As positive control, lysates of cells derived from renal carcinoma (RCC) were used. Three individual experiments were performed with similar results.

HHV-8–induced acute infection and PAX2 expression in HMECs. (A) Subconfluent HMEC monolayers were infected with HHV-8 and analyzed at different productively infected times for virus transcription and release. RT-PCR amplification was performed for the indicated HHV-8 genes using RNA extracted from infected cells. β-actin levels were determined in the same samples as control. Positive controls of amplification of the genes analyzed (C+) are shown. Virus release was evaluated in the culture supernatant by PCR amplification of HHV-8 ORF50 gene. β-actin gene was also amplified to verify the absence of cellular contaminating DNA. (B) Representative micrographs of the same microscopic field observed by phase contrast and by immunofluorescence showing that approximately 20% of the cells stained for the viral HHV-8 antigen ORF K8.1A. Micrographs were obtained by Zeiss Axioskop (Jena, Germany) using 20× objective. (C) Representative confocal micrographs costaining of PAX2 (green) and the viral HHV-8 antigen ORF K8.1A (red) in control uninfected dermal HMECs and renal-HMECs (r-HMECs) and, in HHV-8–infected HMECs, r-HMECs, HMEC-AS, and r-HMEC-AS. Uninfected HMECs and r-HMECs did not express PAX2, but 3 days after infection they showed nuclear staining for PAX2. HHV-8 infection failed to induce PAX2 expression in HMEC-AS and r-HMEC-AS (Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a helium/neon 543 mm laser, an argon 450 to 530 mm laser, and an EC planar NEOFluar 40×/1.3 oil DIC objective lens; acquisition software, Zeiss LSMS, version 3.2). (D) Representative RT-PCR showing the expression of PAX2 mRNA in cells derived from renal carcinoma used as positive control (lane 2), in HMECs infected with HHV-8 after 8 hours (lane 3), 16 hours (lane 4), 24 hours (lane 5), and 3 days (lane 6) and in HMEC-AS infected with HHV-8 after 8 hours (lane 7), 16 hours (lane 8), 24 hours (lane 9), and 3 days (lane 10). (E) Representative Western blot analysis of PAX2 protein expression by HMECs and HMEC-AS after 8 hours, 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after HHV-8 infection showing a band corresponding to 46 kDa. As positive control, lysates of cells derived from renal carcinoma (RCC) were used. Three individual experiments were performed with similar results.

HHV-8 infection induced PAX2 expression in HMECs but not in HMEC-AS

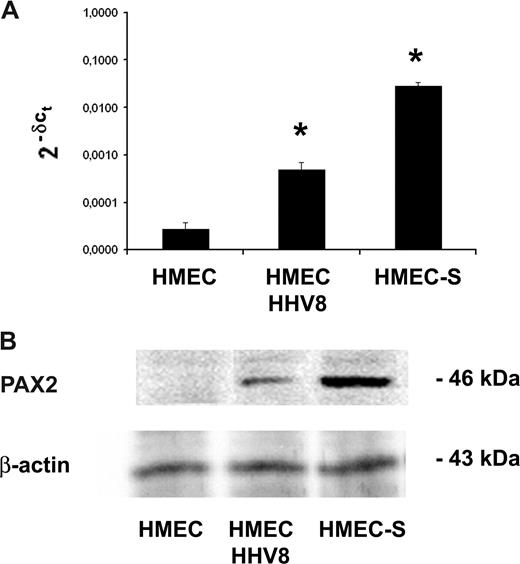

Uninfected HMECs and r-HMECs did not express PAX2 (Figure 1B). The infection of HMECs and r-HMECs with HHV-8-induced PAX2 expression as detected by immunofluorescence (Figure 1B), RT-PCR (Figure 1C), and Western blot analysis (Figure 1D). PAX2 expression became detectable 3 days after infection and persisted at day 7 correlating with the phase of the productive infection. At day 14, the expression of PAX2 protein decreased but was still present (Figure 1D). To inhibit the synthesis of PAX2 protein after the HHV-8 infection, HMECs were stably transfected with an antisense vector for PAX2 (HMEC-AS). The in vitro proliferative behavior of HMEC-AS (0.176 ± 0.02 optical density [OD] at 405 nm) did not significantly differ from control cells not transfected (0.182 ± 0.026 OD at 405 nm) or transfected with an empty vector (0.170 ± 0.018 OD at 405 nm). In addition, HHV-8 infection of HMEC-AS showed the same time course and pattern as HMECs. When infected with HHV-8, these cells no longer expressed PAX2 (Figure 1B-D). The expression of PAX2 after HHV-8 infection was not abrogated when HMECs were transfected with the empty vector as control (data not shown). Figure 2 shows the comparison of the level of PAX2 gene and protein expression induced by HHV-8 infection with that induced by the transfection of HMECs with PAX2 sense vector.

Comparison of PAX2 protein and mRNA expression in HMEC-S and in HMEC/HHV-8. (A) PAX2 mRNA expression analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR was performed for using RNA extracted from HMEC-S stably transfected with sense vector of PAX2 and HMECs infected with HHV-8. The normalized expression of PAX2 gene with respect to beta2 microglobulin was computed for all samples. Values are fold changes with respect to control and are the mean plus or minus SD of 2 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was performed (* P < .05, HMEC-S and HMECs/HHV-8 vs control HMECs). (B) Representative Western blot analysis of PAX2 protein expression by control HMECs, HMEC-S, and HMECs 3 days after HHV-8 infection showing a band corresponding to 46 kDa.

Comparison of PAX2 protein and mRNA expression in HMEC-S and in HMEC/HHV-8. (A) PAX2 mRNA expression analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR was performed for using RNA extracted from HMEC-S stably transfected with sense vector of PAX2 and HMECs infected with HHV-8. The normalized expression of PAX2 gene with respect to beta2 microglobulin was computed for all samples. Values are fold changes with respect to control and are the mean plus or minus SD of 2 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was performed (* P < .05, HMEC-S and HMECs/HHV-8 vs control HMECs). (B) Representative Western blot analysis of PAX2 protein expression by control HMECs, HMEC-S, and HMECs 3 days after HHV-8 infection showing a band corresponding to 46 kDa.

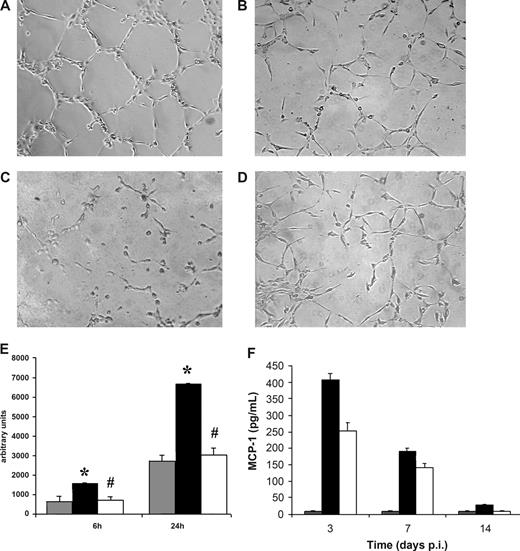

HHV-8–infected HMECs, but not HMEC-AS, acquired the ability to form in vitro capillary-like structures

To evaluate whether HHV-8 infection enhanced the in vitro angiogenesis by a mechanism dependent on PAX2 expression, we studied the ability to form in vitro capillary-like structures by HHV-8–infected HMECs and HMEC-AS compared with control uninfected HMECs (Figure 3A-E). The extent of capillary-like structure on Matrigel was significantly enhanced in HHV-8–infected HMECs, which express PAX2, in respect to control uninfected HMECs. In contrast, the formation of capillary-like structures by HHV-8–infected HMEC-AS, which did not express PAX2, was not significantly different from control uninfected HMECs.

HHV-8 induced in vitro neoangiogenesis and MCP-1 production in HMECs but not in HMEC-AS. The ability of endothelial cells to form capillary-like structures within Matrigel was evaluated. Uninfected and HHV-8-infected HMECs and HMEC-AS (5 × 104) harvested 3 days after infection were seeded on growth factor–reduced Matrigel in RPMI plus 1% FCS, and the extent of capillary-like structure formation was observed after 6 and 24 hours. (A-D) Representative micrographs showing the network of capillary-like structures formed by HMECs (A) and HMEC-AS (B) infected with HHV-8, by HMECs coincubated with blocking MCP-1 antibody (C), and uninfected HMECs (D) after 24 hours of incubation. (E) Morphometric evaluation of ring-like structures formed within Matrigel (gray columns, uninfected HMEC; black columns, infected HMEC; white columns, infected HMEC-AS). Data are mean plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate detected by Nikon Eclipse TE 200 inverted microscope (objectives, 10×/0.25; Tokyo, Japan), analyzed by the Micro-image system (Casti Imaging), and expressed as arbitrary units by the computer analysis system at ×100 magnifications. Analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, infected HMECs vs uninfected HMEC; #P < .05, infected HMEC-AS vs infected HMECs). (F) HMECs or HMEC-AS were infected with HHV-8. At the indicated productively infected times, culture supernatant was analyzed for the release of the MCP-1 by standard quantitative ELISA assays. Levels of chemokines are total pg/mL. Columns represent the same variables as listed for panel E. Bars represent the mean plus or minus SD of triplicate samples. Control is represented by supernatant of uninfected HMECs.

HHV-8 induced in vitro neoangiogenesis and MCP-1 production in HMECs but not in HMEC-AS. The ability of endothelial cells to form capillary-like structures within Matrigel was evaluated. Uninfected and HHV-8-infected HMECs and HMEC-AS (5 × 104) harvested 3 days after infection were seeded on growth factor–reduced Matrigel in RPMI plus 1% FCS, and the extent of capillary-like structure formation was observed after 6 and 24 hours. (A-D) Representative micrographs showing the network of capillary-like structures formed by HMECs (A) and HMEC-AS (B) infected with HHV-8, by HMECs coincubated with blocking MCP-1 antibody (C), and uninfected HMECs (D) after 24 hours of incubation. (E) Morphometric evaluation of ring-like structures formed within Matrigel (gray columns, uninfected HMEC; black columns, infected HMEC; white columns, infected HMEC-AS). Data are mean plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate detected by Nikon Eclipse TE 200 inverted microscope (objectives, 10×/0.25; Tokyo, Japan), analyzed by the Micro-image system (Casti Imaging), and expressed as arbitrary units by the computer analysis system at ×100 magnifications. Analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, infected HMECs vs uninfected HMEC; #P < .05, infected HMEC-AS vs infected HMECs). (F) HMECs or HMEC-AS were infected with HHV-8. At the indicated productively infected times, culture supernatant was analyzed for the release of the MCP-1 by standard quantitative ELISA assays. Levels of chemokines are total pg/mL. Columns represent the same variables as listed for panel E. Bars represent the mean plus or minus SD of triplicate samples. Control is represented by supernatant of uninfected HMECs.

HHV-8 infection induced MCP-1 expression in HMECs

We have recently shown that in vitro infection of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) with HHV-8 induces a marked release of the chemotactic chemokine MCP-1, and that the induction of MCP-1 is a central event in HHV-8–induced angiogenesis of HUVECs.28 Therefore, we evaluated whether HHV-8 infection induced MCP-1 production also in HMECs. Supernatants were collected from HHV-8–infected cells at 3, 7, and 14 days after infection and analyzed for the presence of MCP-1 by specific ELISA test. The results show that HMECs express low basal levels of MCP-1 (< 10 pg/mL) and that HHV-8 infection results in a strong MCP-1 induction (> 400 pg/mL, 3 days after infection), still detectable 7 days after infection (Figure 3F). Because silencing of PAX2 resulted in the inhibition of the in vitro tubule-like structures induced by HHV-8 in HMECs, we evaluated whether PAX-2 expression was correlated to MCP-1 induction. Therefore, we analyzed supernatants from HHV-8–infected HMEC-AS for the presence of MCP-1. The results show that HMEC-AS had more than 40% reduced capacity of releasing MCP-1 on HHV-8 infection, compared with control cells (250 pg/mL at 3 days after infection), which was present at all the analyzed time points (Figure 3F). Addition of anti-MCP-1 antibodies resulted in a strong inhibition of tube formation (Figure 3C).

HHV-8–infected HMECs, but not HMEC-AS, showed enhanced leukocyte adhesion and ICAM-1 expression

Infection of HMECs but not HMEC-AS induced a significant increase in surface expression of ICAM-1 3 days after HHV-8 challenge both in dermal (Figure 4A) and r-HMECs (not shown). A significant increase of leukocyte adhesion was observed in HMECs and r-HMECs 3 days after HHV-8 infection in respect to uninfected control HMECs, r-HMECs, or HHV-8–infected HMEC-AS (Figure 4B). Anti–ICAM-1–blocking antibody abolished the enhanced adhesion induced by HHV-8 infection, suggesting that the expression of ICAM-1 adhesion molecule was the main effector of adhesion. The concomitant absence of enhanced adhesion and ICAM-1 expression in HMEC-AS infected with HHV-8 suggest the dependency on PAX2 expression.

HHV-8 infection induced the expression of ICAM-1 in HMECs but not in HMEC-AS and enhanced leukocytes adhesion that correlated with the expression of PAX2 by HMECs. (A) The expression of ICAM-1 by HMECs and HMEC-AS 3 days after infection with HHV-8 was evaluated by fluorescent-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis and compared with control uninfected HMECs. Cells were detached with nonenzymatic solution and incubated with specific primary antibody for 30 minutes and finally with PE goat anti–mouse IgG for 20 minutes. FACS histograms are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. (B) The adhesion of leukocytes to endothelium was evaluated. Labeled lymphocytes were added to a monolayer of uninfected HMECs and r-HMECs or HMECs, r-HMEC-AS, and HMEC-AS infected with HHV-8 after 3 days and were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere in static condition. After washing, adherent cells were counted in each well. In some experiments, endothelial monolayers were incubated with an anti-ICAM-1 blocking antibody to verify whether enhanced leukocytes adhesion depended on HHV-8–induced expression of ICAM-1. Data are means plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .005, infected HMECs vs uninfected HMEC; #P < .05, infected r-HMECs vs uninfected r-HMECs).

HHV-8 infection induced the expression of ICAM-1 in HMECs but not in HMEC-AS and enhanced leukocytes adhesion that correlated with the expression of PAX2 by HMECs. (A) The expression of ICAM-1 by HMECs and HMEC-AS 3 days after infection with HHV-8 was evaluated by fluorescent-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis and compared with control uninfected HMECs. Cells were detached with nonenzymatic solution and incubated with specific primary antibody for 30 minutes and finally with PE goat anti–mouse IgG for 20 minutes. FACS histograms are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. (B) The adhesion of leukocytes to endothelium was evaluated. Labeled lymphocytes were added to a monolayer of uninfected HMECs and r-HMECs or HMECs, r-HMEC-AS, and HMEC-AS infected with HHV-8 after 3 days and were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C, 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere in static condition. After washing, adherent cells were counted in each well. In some experiments, endothelial monolayers were incubated with an anti-ICAM-1 blocking antibody to verify whether enhanced leukocytes adhesion depended on HHV-8–induced expression of ICAM-1. Data are means plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .005, infected HMECs vs uninfected HMEC; #P < .05, infected r-HMECs vs uninfected r-HMECs).

HHV-8-infected HMECs, but not HMEC-AS, showed enhanced motility and Matrigel invasion

The motility of HHV-8-infected HMECs and HMEC-AS was studied by time lapse recording migration assay (Figure 5A). Control HMECs remained steady for the entire period of observation, never exceeding 10 μm/hour. The infection significantly enhanced migration of HMECs, which reached a speed of approximately 30 μm/hour and remained sustained for the whole period of observation. To test the role of PAX2 expression in the enhanced migration triggered by HHV-8 infection, the motility of HHV-8–infected HMECs and HMEC-AS was compared. The inhibition of PAX2 expression in HMEC-AS was associated with a significant reduction of motility.

HHV-8 induced in vitro endothelial cells motility and invasion correlated with the expression of PAX2. (A) The motility of uninfected HMECs (o), HHV-8–infected HMECs (■) and HHV-8-infected HMEC-AS (▲) was monitored by time-lapse analysis and measured in μm/h as described in “Cell motility.” Results are mean plus or minus SD of 3 individual experiments. ANOVA with Dunnett multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, infected HMECs, infected HMEC-AS, and uninfected HMECs). (B) The invasion of Matrigel-coated filters by uninfected HMECs or HMECs and HMEC-AS infected with HHV-8 was evaluated. Cells were seeded onto Matrigel precoated upper well (100 μg/well) and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2, in a humidified atmosphere. The lower wells were loaded with medium plus 10% FCS. Cells that migrated to the underside of the filters were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa solution, and counted in 5 microscopic fields in each well. Data are mean plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. ANOVA with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, infected HMECs vs uninfected HMEC; #P < .05, infected HMEC-AS vs infected HMECs). (C) Representative zymographic analysis of uninfected HMECs (lane 2), HMECs (lane 3), and HMEC-AS (lane 4) 3 days after infection with HHV-8; HMECs (lane 5) and HMEC-AS (lane 6) 7 days after infection with HHV-8; HMECs (lane 7) and HMEC-AS (lane 8) 14 days after infection with HHV-8. Lane 1 shows the control RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS (lane 1). Three experiments were performed with similar results.

HHV-8 induced in vitro endothelial cells motility and invasion correlated with the expression of PAX2. (A) The motility of uninfected HMECs (o), HHV-8–infected HMECs (■) and HHV-8-infected HMEC-AS (▲) was monitored by time-lapse analysis and measured in μm/h as described in “Cell motility.” Results are mean plus or minus SD of 3 individual experiments. ANOVA with Dunnett multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, infected HMECs, infected HMEC-AS, and uninfected HMECs). (B) The invasion of Matrigel-coated filters by uninfected HMECs or HMECs and HMEC-AS infected with HHV-8 was evaluated. Cells were seeded onto Matrigel precoated upper well (100 μg/well) and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2, in a humidified atmosphere. The lower wells were loaded with medium plus 10% FCS. Cells that migrated to the underside of the filters were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa solution, and counted in 5 microscopic fields in each well. Data are mean plus or minus SD of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. ANOVA with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, infected HMECs vs uninfected HMEC; #P < .05, infected HMEC-AS vs infected HMECs). (C) Representative zymographic analysis of uninfected HMECs (lane 2), HMECs (lane 3), and HMEC-AS (lane 4) 3 days after infection with HHV-8; HMECs (lane 5) and HMEC-AS (lane 6) 7 days after infection with HHV-8; HMECs (lane 7) and HMEC-AS (lane 8) 14 days after infection with HHV-8. Lane 1 shows the control RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS (lane 1). Three experiments were performed with similar results.

During angiogenesis, endothelial cells acquired the ability to invade basal membrane.29 Recently, we demonstrated that transfection of normal HMECs with PAX2 sense vector conferred enhanced invasion properties similar to that of tumor-derived endothelial cells.23

To test whether the enhanced invasiveness of HMECs infected with HHV-8 was dependent on the expression of PAX2, we compared the ability to invade Matrigel in vitro of HHV-8–infected HMECs and HMEC-AS (Figure 5B). The HHV-8 infection significantly enhanced invasion ability in HMECs with respect to uninfected control HMECs. In contrast, the infection of HMEC-AS did not significantly enhance Matrigel invasion.

To evaluate whether enhanced Matrigel invasion correlated with secretion of MMPs, we tested the gelatinolytic ability of HHV-8–infected HMECs and HMEC-AS (Figure 5C). The supernatants of HMECs and HMEC-AS were collected after 3, 7, and 14 days of infection. Results showed pro–MMP-9 secretion in all of supernatants tested. However, we detected a band of 83 kDa, corresponding to the active form of MMP-9, at 3 and 7 days of infection in HMECs, but not in HMEC-AS or uninfected control HMECs. Together, these data demonstrated an increase of the gelatinolytic activity accompanied with an enhanced in vitro invasion ability of HHV-8–infected HMECs. The absence of enhanced invasion and expression of the active form of MMP-9 in HHV-8–infected HMEC-AS suggests a critical role of PAX2 expression.

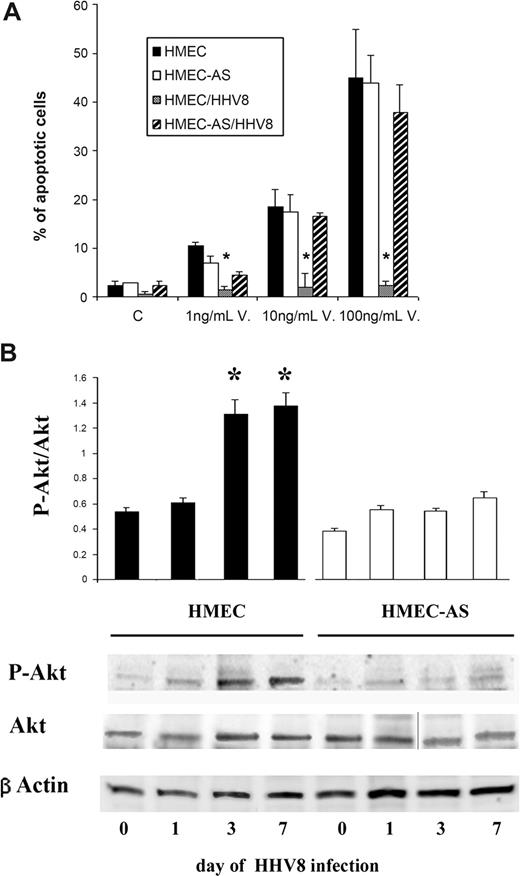

HHV-8–infected HMECs, but not HMEC-AS, showed resistance to apoptosis and enhanced activation of Akt pathway

As shown in Figure 6A, apoptosis induced by vincristine was inhibited by HHV-8 infection in HMECs but not in HMEC-AS, suggesting that PAX2 expression is instrumental in apoptosis resistance triggered by the HHV-8 infection.

PAX2 expression after HHV-8 infection was associated with apoptosis resistance and activation of Akt-dependent pathway. (A) Apoptosis was evaluated by the terminal dUTP nick-end labeling assay as a percentage of apoptotic cells after 24 hours of incubation. Control cells were incubated in the presence of 20% of serum. Apoptosis was induced by treatment with increasing doses of vincristine. Data are mean plus or minus SD of 3 individual experiments. Analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, HMEC HHV-8 infected vs uninfected HMECs). (B) Phosphorylation of Akt was evaluated 1, 3, and 7 days after infection with HHV-8 of HMECs and HMEC-AS. (A) Densitometric analysis of P-Akt/Akt ratio and representative Western blots performed on 3 individual experiments; data are mean plus or minus SD of 3 individual experiments. Analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, HMECs after 3 and 7 days of infection vs HMECs before infection, day 0; #P < .05, infected HMEC-AS vs infected HMECs). (B) Representative Western blot analysis of P-Akt and Akt and β-actin of cell lysates from HMECs and HMEC-AS before and after infection with HHV-8. A vertical line has been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane. Three experiments were performed with similar results.

PAX2 expression after HHV-8 infection was associated with apoptosis resistance and activation of Akt-dependent pathway. (A) Apoptosis was evaluated by the terminal dUTP nick-end labeling assay as a percentage of apoptotic cells after 24 hours of incubation. Control cells were incubated in the presence of 20% of serum. Apoptosis was induced by treatment with increasing doses of vincristine. Data are mean plus or minus SD of 3 individual experiments. Analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, HMEC HHV-8 infected vs uninfected HMECs). (B) Phosphorylation of Akt was evaluated 1, 3, and 7 days after infection with HHV-8 of HMECs and HMEC-AS. (A) Densitometric analysis of P-Akt/Akt ratio and representative Western blots performed on 3 individual experiments; data are mean plus or minus SD of 3 individual experiments. Analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test was performed (*P < .05, HMECs after 3 and 7 days of infection vs HMECs before infection, day 0; #P < .05, infected HMEC-AS vs infected HMECs). (B) Representative Western blot analysis of P-Akt and Akt and β-actin of cell lysates from HMECs and HMEC-AS before and after infection with HHV-8. A vertical line has been inserted to indicate a repositioned gel lane. Three experiments were performed with similar results.

Furthermore, HHV-8 infection of HMECs induced a significant enhancement of Akt phosphorylation as detected 3 and 7 days after infection. In contrast, infection of HMEC-AS failed to increase the P-Akt/Akt ratio (Figure 6B). These results suggest that the enhanced activation of Akt survival pathway by HHV-8 infection occurred only in cells able to express PAX2.

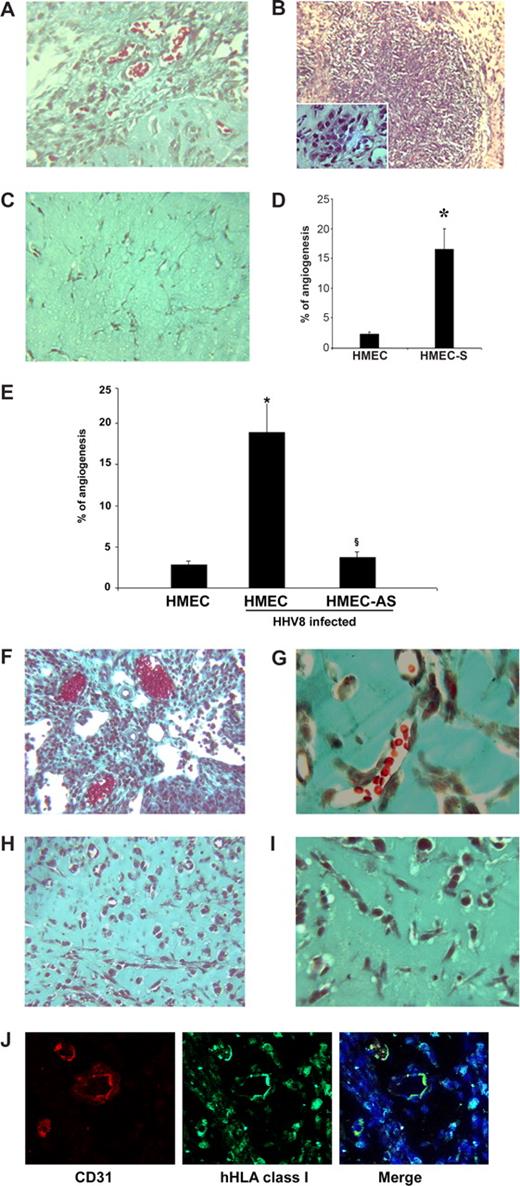

Expression of PAX2 by HMECs induced increased in vivo angiogenesis and KS-like lesions in SCID mice

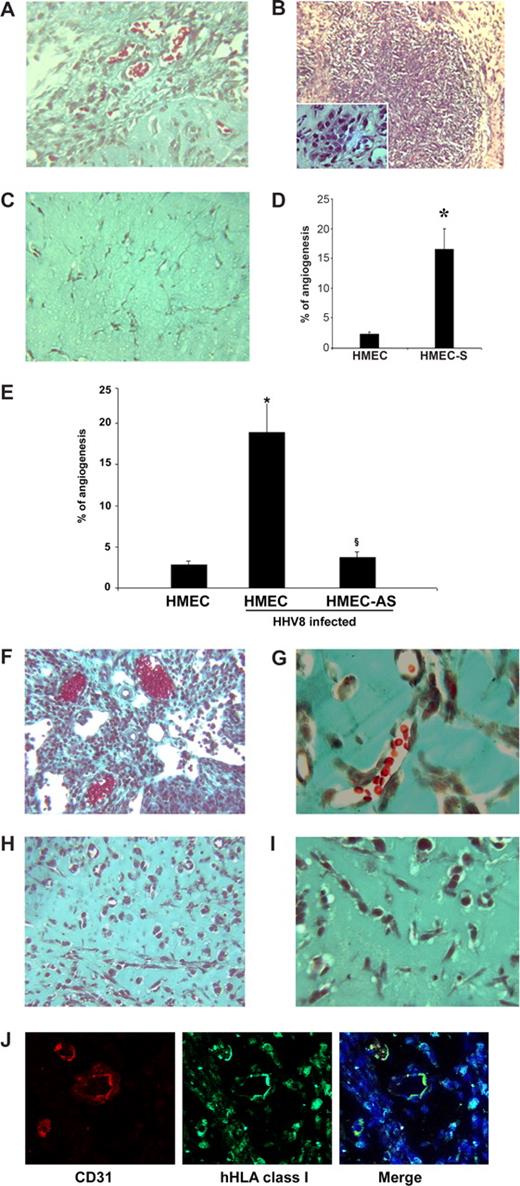

To investigate whether the expression of PAX2 by HMECs induced in vivo angiogenesis and KS-like lesions, we evaluated the effect of subcutaneous injection in SCID mice of HMECs transfected with sense PAX2 vector (HMEC-S) within diluted Matrigel. After 6 days, we observed areas of extensive vascularization and focal formation of structures similar to that of KS lesions. The cells within the lesions acquired characteristic spindle shape morphology (Figure 7A-D). In control HMECs transfected with the empty vector, the vessel formation was minimal and the proliferative lesions were absent (Figure 7C,D). Moreover, to evaluate whether HHV-8 infection induced similar results, we injected HHV-8–infected HMECs and HMEC-AS subcutaneously within diluted Matrigel in SCID mice. Results showed that acquirement of PAX2 expression after HHV-8 infection conferred enhanced angiogenic properties to HMECs that spontaneously organized in microvessels containing blood cells and formed proliferative vascularized lesions (Figure 7E-G). This angiogenic ability was not acquired by HMEC-AS in which PAX2 expression was inhibited (Figure 7E,H,I). The human origin of vessels formed within Matrigel was verified by immunofluorescence for HLA class I and for human CD31 (Figure 7J).

Kaposi-like lesions in SCID mice injected with PAX2-expressing HMECs and in vivo angiogenesis induced by uninfected or HHV-8–infected HMECs and HMEC-AS. (A-D) HMECs (106) transfected with sense cDNA coding for PAX2 and control HMECs transfected with the empty vector were injected in diluted Matrigel subcutaneously in SCID mice. Mice were killed after 6 days, and Matrigel plugs were submitted to histologic analysis. (A-C) Representative micrographs of Matrigel-containing HMEC-S (A,B) and control HMECs (C). HMEC-S showed formation of vessels containing blood erythrocytes (A; Masson trichrome staining) and proliferative lesions (B; hematoxylin/eosin staining). Inset shows the presence of spindle-shaped cells. Angiogenesis and proliferative lesions were absent in control HMECs (C; Masson trichrome staining). (D) Morphometric analysis of new formed vessels within Matrigel. Data are mean plus or minus SD of 5 individual experiments. Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was performed (*P < .05, HMEC-S vs control HMECs). (E-J) Cells were implanted subcutaneously in SCID mice within growth factor-reduced Matrigel, and the formation of organized vascular structures was evaluated after 6 days. (E) Morphometric analysis of vessels formed in section of Matrigel plugs stained by Masson's trichrome staining. Only the vascular structures containing red blood cells were counted as vessels. Data are mean plus or minus SD of 5 individual experiments. Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was performed (*P < .05, HHV-8–infected HMECs vs uninfected HMEC; §P < .05, infected HMEC-AS vs infected HMECs). (F-I) Representative micrographs showing the proliferative lesions and the formation of canalized vessels in mice implanted with HMECs infected with HHV-8 (F,G) and absence of proliferative lesions and of patent vessels in mice implanted with HMEC-AS infected with HHV-8 (H,I). (J) Representative micrographs showing the human nature of vessels formed by HHV-8-infected HMECs. The sections of Matrigel plugs were staining with antihuman CD31 and hHLA class I as described in “In vivo angiogenesis assay.” Pictures were obtained using a Zeiss LSM5 Pascal confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a Helium/Neon 543 mm laser, an Argon 450-530 mm laser and an EC planar NEORFluar 63×/1.3 oil DIC objective lens. Acquisition software was Zeiss LSMS version 3.2. Original magnifications were ×150 (A-C,F,H,J), ×250 (G,I).

Kaposi-like lesions in SCID mice injected with PAX2-expressing HMECs and in vivo angiogenesis induced by uninfected or HHV-8–infected HMECs and HMEC-AS. (A-D) HMECs (106) transfected with sense cDNA coding for PAX2 and control HMECs transfected with the empty vector were injected in diluted Matrigel subcutaneously in SCID mice. Mice were killed after 6 days, and Matrigel plugs were submitted to histologic analysis. (A-C) Representative micrographs of Matrigel-containing HMEC-S (A,B) and control HMECs (C). HMEC-S showed formation of vessels containing blood erythrocytes (A; Masson trichrome staining) and proliferative lesions (B; hematoxylin/eosin staining). Inset shows the presence of spindle-shaped cells. Angiogenesis and proliferative lesions were absent in control HMECs (C; Masson trichrome staining). (D) Morphometric analysis of new formed vessels within Matrigel. Data are mean plus or minus SD of 5 individual experiments. Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was performed (*P < .05, HMEC-S vs control HMECs). (E-J) Cells were implanted subcutaneously in SCID mice within growth factor-reduced Matrigel, and the formation of organized vascular structures was evaluated after 6 days. (E) Morphometric analysis of vessels formed in section of Matrigel plugs stained by Masson's trichrome staining. Only the vascular structures containing red blood cells were counted as vessels. Data are mean plus or minus SD of 5 individual experiments. Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was performed (*P < .05, HHV-8–infected HMECs vs uninfected HMEC; §P < .05, infected HMEC-AS vs infected HMECs). (F-I) Representative micrographs showing the proliferative lesions and the formation of canalized vessels in mice implanted with HMECs infected with HHV-8 (F,G) and absence of proliferative lesions and of patent vessels in mice implanted with HMEC-AS infected with HHV-8 (H,I). (J) Representative micrographs showing the human nature of vessels formed by HHV-8-infected HMECs. The sections of Matrigel plugs were staining with antihuman CD31 and hHLA class I as described in “In vivo angiogenesis assay.” Pictures were obtained using a Zeiss LSM5 Pascal confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a Helium/Neon 543 mm laser, an Argon 450-530 mm laser and an EC planar NEORFluar 63×/1.3 oil DIC objective lens. Acquisition software was Zeiss LSMS version 3.2. Original magnifications were ×150 (A-C,F,H,J), ×250 (G,I).

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrated that infection of HMECs with HHV-8–induced PAX2 expression and that this expression conferred to HMECs proangiogenic and proinvasive properties similar to that of KS cells.

Several data suggest that HHV-8 is an etiologic agent responsible for the development of KS.29,–31 Indeed, by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical analysis, the presence of HHV-8 has been detected in spindle-shaped cells of KS.5,32,33 In addition, the endothelial cells infected with HHV-8 underwent morphologic changes similar to that of KS spindle-shaped cells.28,34

In the present study, we observed that HMECs are susceptible to HHV-8 infection and show the same course as HUVECs.28 The infection of endothelial cells with HHV-8 induced the expression of PAX2. PAX2, which is not present in normal endothelial cells, was found to be expressed in tumor endothelial cells, such as those derived from renal carcinomas, and its expression correlated with the pro-invasive characteristic of these cells.23

To evaluate whether the expression of PAX2 induced by HHV-8 infection of endothelial cells was responsible for the KS-like transformation of endothelial cells observed after infection, HMECs were transfected with antisense DNA of PAX2, which inhibited the PAX2 protein translation. Blockade of PAX2 expression resulted in the failure to acquire a KS-like phenotype by HHV-8–infected endothelial cells. To investigate the potential mechanism by which PAX2 may regulate the invasive phenotype, we studied the effect of HHV-8 infection on ICAM-1 adhesion molecule. We found that ICAM-1 was significantly up-regulated in HHV-8-infected HMECs in comparison with HHV-8–infected HMEC-AS and control uninfected HMECs and that ICAM-1 blockade inhibited the HHV-8 enhanced adhesion. Moreover, HHV-8–induced PAX2 expression was associated with an increased motility and Matrigel invasion of endothelial cells. These results correlated with zymographic analysis in which we observed the production of the active MMP-9 (83 kDa) by HMECs after HHV-8 infection. HHV-8–dependent PAX2 expression was also associated with enhanced survival and activation of the Akt activation. Akt phosphorylation was found to correlate with the apoptosis resistance of HHV-8–infected cells This correlation was absent in cells where the expression of PAX2 was impaired, suggesting that PAX2 expression modulates the Akt survival pathway, which is known to be deeply involved in angiogenesis and tumor progression.23,35,36

Recently, we demonstrated that PAX2 expression by KS cells correlated with enhanced resistance against apoptotic signals and with a proinvasive phenotype.9 Furthermore, transfection of HMECs with sense DNA of PAX2 (HMEC-S) induced morphologic changes characteristic of spindle-shape cells observed in KS. In the present study, we demonstrated that HMECs transfected to express PAX2 formed vascularized tumors similar to KS when subcutaneously injected in SCID mice. Moreover, HHV-8–infected HMECs, but not HHV-8–infected HMEC-AS, when injected subcutaneously in SCID mice, formed an angiogenic network and KS-like lesions. These data suggest that the activation of PAX2 gene may influence the angiogenic behavior of endothelial cells contributing to the acquisition of a transformed phenotype.

Recently, we provided evidence that HHV-8 acute infection of HUVEC triggers NF-κB activation and drives a strong selective induction of MCP-1 synthesis.28 MCP-1 production was accompanied by virus-induced capillary-like structure formation in Matrigel. This phenomenon was abolished by anti MCP-1 neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, suggesting that this chemokine has an important role in HHV-8–mediated angiogenesis. The same situation occurs in HHV-8–infected HMECs, with induction of MCP-1 production, tube formation in Matrigel, and inhibition of tube formation by anti–MCP-1 neutralizing antibodies, confirming the important role played by MCP-1 in HHV-8–induced angiogenesis. Furthermore, silencing of PAX2 results in a significant decrease of MCP-1 expression. Therefore, HHV-8 might stimulate MCP-1 synthesis by activation of PAX2, and PAX2-induced proangiogenetic phenotype might be mediated, at least in part, by MCP-1.

It has been suggested that KS spindle cells may originate from vascular precursor endothelial cells infected with HHV-8. Infection induces the acquisition of spindle cell morphology, increases life span and proliferation,7,8 and triggers the expression of proinflammatory chemokines.37 In this context, the results of the present study indicate that PAX2 oncogene might be an important determinant of the angiogenic phenotype acquired by HHV-8–infected endothelial cells. Indeed, the expression of PAX2, induced by HHV-8 infection, might account for events involved in growth and invasion of this angiogenic tumor, such as enhanced expression of adhesion molecules, increased chemokine secretion, resistance to apoptosis, enhanced migration, and invasion.

In conclusion, our results suggest a crucial role of PAX2 expression, induced by HHV-8 infection, in the transformation of endothelial cells in KS-like cells and in the acquisition of a proangiogenic and proinvasive phenotype.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Linda M. Sartor for revision of the English manuscript.

This work was supported by Istituto Superiore Sanità, Progetto AIDS (Progetti 40G13, 50G12), the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, the Italian Ministry of University and Research PRIN and ex60%, Regione Piemonte integrated project A47, Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata 02), and Progetto S. Paolo (G.C.).

Authorship

Contribution: D.D.L. and G.C. designed the research; V.F., S.B., M.C.D., B.B., and E.C. performed the research; and V.F., B.B., D.D.L., E.C., and G.C. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dario Di Luca, Department of Experimental and Diagnostic Medicine, University of Ferrara, Via Borsari 46, 44100 Ferrara, Italy; e-mail: ddl@unife.it.