From April 2003 to December 2006, 195 patients with de novo symptomatic myeloma and younger than 60 years of age were randomly assigned to receive either tandem transplantation up front (arm A, n = 97) or one autologous stem-cell transplantation followed by a maintenance therapy with thalidomide (day + 90, 100 mg per day during 6 months) (arm B, n = 98). Patients included in arm B received a second transplant at disease progression. In both arms, autologous stem-cell transplantation was preceded by first-line therapy with thalidomide-dexamethasone and subsequent collection of peripheral blood stem cells with high-dose cyclophosphamide (4 g/m2) and granulocyte colony stimulating factor. Data were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis. With a median follow-up of 33 months (range, 6–46 months), the 3-year overall survival was 65% in arm A and 85% in arm B (P = .04). The 3-year progression-free survival was 57% in arm A and 85% in arm B (P = .02). Up-front single autologous transplantation followed by 6 months of maintenance therapy with thalidomide (with second transplant in reserve for relapse or progression) is an effective therapeutic strategy to treat multiple myeloma patients and appears superior to tandem transplant in this setting. This study was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as (NCT 00207805).

Introduction

Two prospective randomized studies have shown that recipients of high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) have superior survival when compared with patients treated with conventional therapy.1,2 In both studies, patients were younger than 65 years, and as a result, single ASCT is now considered a standard option in younger patients.1,–3

The Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) was the first to demonstrate that 2 sequential ASCTs improved 7-year event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) rates in comparison with a single ASCT.4 Recently, the Bologna 96 clinical study has shown that in comparison with a single ASCT as up-front therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM), double ASCT effected superior complete response (CR) rate and EFS but failed to significantly prolong OS. Benefits offered by double ASCT were particularly evident among patients who did not achieve at least a very good partial response (VGPR) after one autotransplantation.5

Second ASCT given after relapse following a single ASCT has been used as a salvage therapy in many centers.6,,,,–11 Recently, a retrospective study has compared tandem ASCT up front with a strategy including planned second ASCT at relapse or progression.12 In this retrospective study, Morris et al12 showed that a second ASCT performed before relapse and within 6 to 12 months of the first ASCT improved survival.

While there have been no randomized trials to evaluate the benefit of second ASCT following relapse, it has been suggested that ASCT (after first relapse) may achieve the same outcome as transplantation following initial therapy.13,–15 Indeed, Fermand et al13 showed that early transplantation improved EFS but did not affect OS when compared with delayed transplantation.

Although MM remains incurable with conventional treatments, management of the disease recently has been transformed with the introduction of 3 novel agents: bortezomib,16 thalidomide,17 and lenalidomide.18 These agents represent a new generation of treatments for MM that affect both specific intracellular signaling pathways and the tumor microenvironment.19 Thalidomide is an agent with immunomodulatory and antiangiogenic properties. Thalidomide plus dexamethasone20,–22 is currently approved as frontline treatment of MM. Furthermore, several studies have shown that thalidomide is an effective maintenance therapy after ASCT in patients with MM.23,–25

We therefore performed a multicenter, randomized trial designed to compare tandem ASCT up front with one ASCT followed by maintenance therapy with thalidomide and a second ASCT after relapse or progression.

Methods

Requirements for patient enrollment

Eligibility criteria included age younger than 60 years, a Durie-Salmon stage II or III myeloma, and previously untreated patients. Patients were excluded if they had one of the following criteria: prior malignancy, pregnant or nursing women, refusal of contraception, patients with ECOG performance score of 4, positive HIV test, psychiatric disease, severe abnormalities of cardiac (systolic ejection fraction < 50%), pulmonary (vital capacity or carbon monoxide diffusion < 50% of normal), liver (serum bilirubin > 35 μM or ALAT, ASAT > 4 times normal), and renal functions (serum creatinine level of more than 300 μM). The study protocol was approved by the national medical ethical committee, and a written informed consent was obtained from the patients, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as number NCT 00207805.

Study protocol

Initial enrollment.

Between April 2003 and December 2006, patients were registered by the coordinating center (Centre National de Greffe de Moelle Osseuse, Tunis), and a centralized analysis of β-2 microglobulin (Institut Pasteur, Tunis) and conventional cytogenetics were performed (Sousse, and Institut Pasteur, Tunis).

Induction therapy.

During the first-line therapy, thalidomide was administered at a dose of 200 mg per day for 75 consecutive days, and dexamethasone was administered at a dose of 20 mg/m2 body surface area on days 1 to 4, 9 to 12, and 17 to 20 on the first and the third month of therapy and at 20 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4, the second month. During the first-line therapy, patients received therapeutic doses of prophylactic anticoagulation with acenocoumarol (international normalized ratio of the prothrombin time: 2–3).

Stem cell collection.

After first-line therapy, patients who proceeded to peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) collection received high-dose cyclophosphamide (4 g/m2) and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF, 5 μg/kg/day). A minimum of 6 million CD34 cells per kilogram was collected.

Randomization.

After PBSC, patients were randomly assigned to receive one of the following treatment arms: arm A, 2 successive ASCTs. The conditioning regimen of the first ASCT consisted of melphalan at a dose of 200 mg/m2. The second ASCT was administered within 6 months of the first ASCT, with the same conditioning regimen. In case of disease progression or relapse after second ASCT, patients included in arm A received thalidomide as salvage therapy (200 mg/day); arm B, one ASCT with a conditioning regimen with melphalan 200 mg/m2 followed by maintenance therapy with thalidomide at a dose of 100 mg per day, starting 3 months after the ASCT. The duration of maintenance thalidomide was 6 months. Patients included in arm B received a second ASCT in case of disease progression or relapse.

Assessments

The response criteria of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation proposed in 1998 were used in this study,26 with the addition of a VGPR.27 A CR was defined as the lack of detectable paraprotein by serum and urine immunofixation and 5% or fewer plasma cells with normal morphological features in a bone marrow aspirate. A VGPR was defined as a 90% decrease in the serum paraprotein level; a partial response (PR) as a 50% decrease in the paraprotein level or a 90% decrease in the level of Bence Jones protein (including patients with Bence Jones protein alone) or both; a minimal response (MR) was defined as a 25% decrease in the serum paraprotein level; stable disease as no change in the paraprotein level; a progression as a 25% increase in the serum paraprotein level; and a relapse as the reappearance of the paraprotein and/or the recurrence of bone marrow infiltration in a patient with a prior CR. A skeletal survey was performed according to the guideline of the United Kingdom myeloma forum.28

Statistical analysis

The proportion of patients with a given characteristic were compared by chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Differences in the means of continuous measurements were tested by Student t test and checked with the use of the Mann-Whitney U test. The duration of progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated for patients randomly assigned from the date of random assignment to the time of progression, relapse, or death. The primary end point of this study was OS from randomization. Secondary end point was PFS. The expected OS in arm A is approximately 60% at 5 years. To have an 80% chance of detecting a 20% difference in OS (ie, an OS of 80% in arm B) at 5 years with an alpha value of 5% using a 2-sided test required 184 patients to be randomized. All comparisons were performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the use of the log-rank test, using June 1, 2007, as the reference date. Prognostic factors for survival were determined by means of the Cox proportional-hazards model for covariate analysis. The study was completed after 195 patients had been randomly assigned.

Results

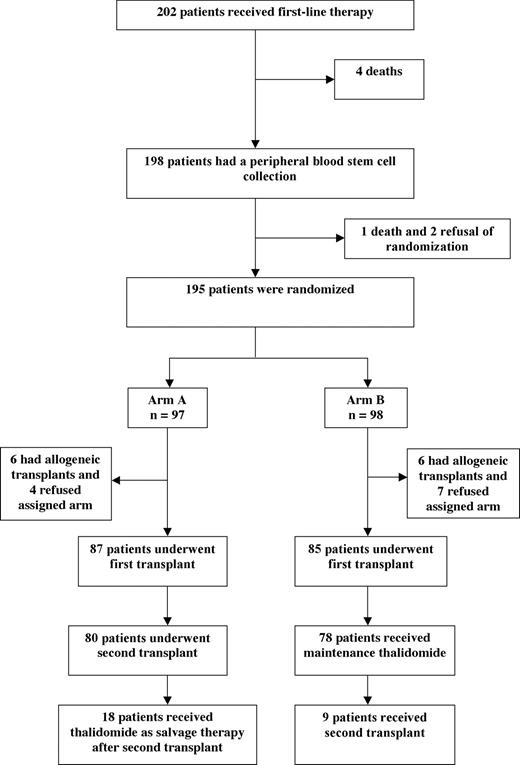

Patient flow (Figure 1)

During this 49-month study, 202 patients were enrolled and received first-line therapy with thalidomide and dexamethasone. We observed 4 deaths due to infections during first-line therapy.

The first 13 patients who received dexamethasone-thalidomide were not given prophylaxis of deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Among these first 13 patients, 2 (15%) had symptomatic DVT. Because of the high rate of DVT observed in this first group, therapeutic doses of prophylactic anticoagulation with acenocoumarol were given for the remaining 189 patients. No further DVTs were observed subsequent to the addition of anticoagulant.

A peripheral blood stem-cell collection was performed in 198 patients. A median number of 8 million CD34 cells per kilogram was collected (range, 6.5–36).

Three patients were excluded, because of one death and 2 refusals of randomization. Ultimately, 195 patients were randomized: 97 patients were allocated to arm A, and 98 patients were allocated to arm B. The median time from enrollment to randomization was 3 months (range, 2–4 months).

Completion of assigned therapy

In arm A, 90% of patients underwent the first transplantation, and 82% underwent the second transplantation. The median time from the first to the second transplantation was 5 months (range, 3–6 months). In arm B, 87% of patients underwent the first transplantation and 80% of patients received maintenance thalidomide.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the 195 patients randomly assigned is shown in Table 1. No significant differences were found between the 2 treatment groups.

Response rate

The response rate at each step of the study is shown in Table 2. At 3 months after the first ASCT, on an intention-to-treat basis the overall rates of CR and VGPR in arms A and B were 40% and 41%, respectively (P = .8).

After second ASCT and 6 months of maintenance thalidomide, the overall rates of CR and VGPR in arms A and B were 54% and 68%, respectively (P = .04).

Progression-free survival and overall survival

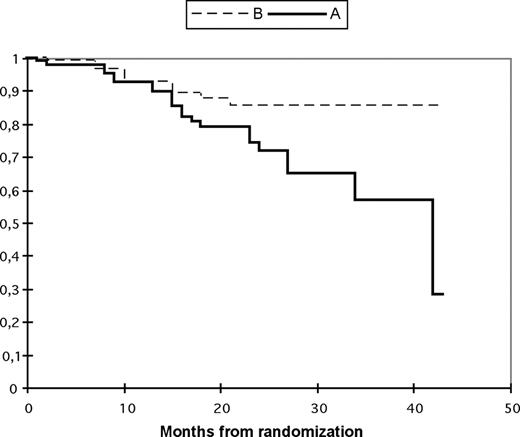

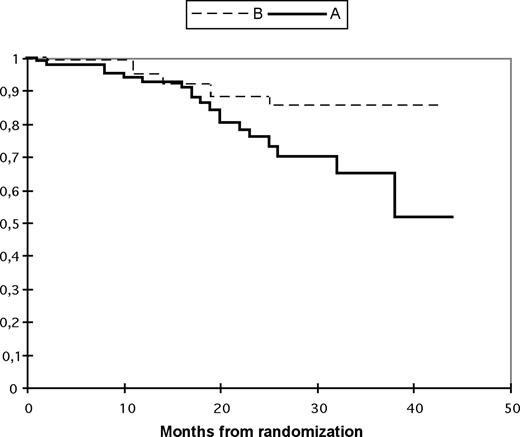

With a median follow-up of 33 months (range, 6–46 months), the 3-year probability of OS was 65% in arm A and 85% in arm B (P = .04). The 3-year PFS was 57% in arm A and 85% in arm B (P = .02; Figures 2,3).

Progression-free survival according to treatment arm. The probabilities of progression-free survival (95% CI) are shown below each time point. Tandem transplantation up front (arm A: —); single autologous followed by maintenance thalidomide and second autologous in case of relapse/progression (arm B:  ). The probability of progression-free survival (95% CI) after randomization at 3 years in arm A is 57% (37–76) and in arm B is 85% (77–94).

). The probability of progression-free survival (95% CI) after randomization at 3 years in arm A is 57% (37–76) and in arm B is 85% (77–94).

Progression-free survival according to treatment arm. The probabilities of progression-free survival (95% CI) are shown below each time point. Tandem transplantation up front (arm A: —); single autologous followed by maintenance thalidomide and second autologous in case of relapse/progression (arm B:  ). The probability of progression-free survival (95% CI) after randomization at 3 years in arm A is 57% (37–76) and in arm B is 85% (77–94).

). The probability of progression-free survival (95% CI) after randomization at 3 years in arm A is 57% (37–76) and in arm B is 85% (77–94).

Overall survival according to treatment arm. The probabilities of overall survival (95% CI) are shown below each time point. Tandem transplantation up front (arm A: —); single autologous followed by maintenance thalidomide and second autologous in case of relapse/progression (arm B:  ). The probability of overall survival (95% CI) after randomization at 3 years in arm A is 65% (49–80) and in arm B is 85% (76–95).

). The probability of overall survival (95% CI) after randomization at 3 years in arm A is 65% (49–80) and in arm B is 85% (76–95).

Overall survival according to treatment arm. The probabilities of overall survival (95% CI) are shown below each time point. Tandem transplantation up front (arm A: —); single autologous followed by maintenance thalidomide and second autologous in case of relapse/progression (arm B:  ). The probability of overall survival (95% CI) after randomization at 3 years in arm A is 65% (49–80) and in arm B is 85% (76–95).

). The probability of overall survival (95% CI) after randomization at 3 years in arm A is 65% (49–80) and in arm B is 85% (76–95).

Prognostic factors for progression-free survival

In a multivariate analysis of all 195 patients randomly assigned, PFS was significantly related to deletion of chromosome 13 (P < .05), β-2 microglobulin (> 3 mg/L; P < .01), and treatment assignment (arm A or arm B; P < .04).

In arm B, the effect of thalidomide on PFS differed according to the response achieved at 3 months after the first transplantation. Patients who had at least a VGPR did not benefit from thalidomide (P = .5). Patients who did not have at least a VGPR had a significant benefit from thalidomide (P < .003).

Treatment-related toxicity

Treatment-related toxicity in each treatment group is shown in Table 3. Of the 19 deaths observed in arm A, 4 were attributed to the toxic effects of ASCT and 15 to disease progression. Of the 9 deaths observed in arm B, 2 were attributed to the toxic effects of ASCT and 7 to disease progression.

In arm B, 78 patients (80%) received maintenance treatment with thalidomide for a median of 6 months (range, 2–6 months) at a fixed dose of 100 mg/day. The adverse events (as defined by the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2) during maintenance treatment with thalidomide are shown in Table 4. Drug-related adverse events led to discontinuation of thalidomide in 7 patients (7 of 78, 9%). Peripheral neuropathy was the main reason for discontinuation.

In arm A, 18 patients received thalidomide as salvage therapy after second ASCT for a median of 4 months (range, 1–6 months), at a fixed dose of 200 mg per day. The adverse events (as defined by the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2) during salvage therapy with thalidomide are shown in Table 4. Drug-related adverse events led to discontinuation of thalidomide in 4 patients (4 of 18, 23%), with peripheral neuropathy as the main reason for discontinuation. Currently, 3 patients (3 of 18, 17%) continue on thalidomide and remain alive and progression free. The remaining 15 patients died due to disease progression.

Discussion

To our knowledge, no randomized studies have examined if it is necessary to perform 2 ASCTs within a limited period or if advantage can be obtained by performing a second ASCT only after the patient has relapsed. In a retrospective study, Morris et al12 showed that a second ASCT performed before relapse and within 6 to 12 months of the first ASCT improved survival.

We compared tandem ASCT with single ASCT followed by maintenance treatment with thalidomide and a second ASCT if needed due to progression or relapse in adults with MM. This study was predicated on previous work published by Fermand et al,13 who showed that early transplantation improved EFS but did not affect OS when compared with delayed transplantation.

We found a higher quality of response with the delayed ASCT strategy versus the standard up-front tandem strategy, as well as a better PFS and OS. The best quality of response observed in arm B with maintenance thalidomide could explain the better PFS in this group. The benefit of maintenance thalidomide was observed only in patients who had not achieved a VGPR following high-dose therapy, suggesting that thalidomide induced a direct cytoreductive effect and additional response, rather than maintaining responses already achieved by ASCT. One hypothesis derived from this observation would be that stopping maintenance thalidomide as soon as a VGPR has been reached could be a more effective strategy to reduce side effects and decrease thalidomide resistance and/or intolerance at time of relapse. These findings warrant further study.

In our study, patients received thalidomide and dexamethasone as induction therapy.29 In the future, it will be important to define whether prior exposure and response to thalidomide induction therapy will have an impact on its use as maintenance treatment.30

This study provides a precedent for use of novel therapies such as thalidomide to help prepare patients for ASCT and as maintenance to sustain a posttransplantation response. However, one caveat in this study is that patients in the tandem ASCT group did not receive thalidomide maintenance therapy. The recently published IFM study by Attal et al has shown that maintenance thalidomide provides a clinical benefit following double ASCT.23

At least the first two-thirds of the curves in Figures 2,3 (progression-free survival vs overall survival) are almost superimposable. Indeed, in most cases we have observed very aggressive relapses, often accompanied with rapid death despite salvage attempts. One explanation could be that many of our patients postpone consulting long after the first clinical symptoms of relapse, and show an advanced state at admission. Another explanation could be the limited options of salvage therapy in our country (eg, Velcade is not available in Tunisia).

In our trial, maintenance therapy with thalidomide was not found to increase the risk of thromboembolic complications. We thus confirm that this risk is mainly observed if thalidomide is given during induction therapy when the tumor burden is high.31,32 It is also in the context of the addition of dexamethasone that the risk of thromboembolic disease increases.33

Recently, Mileshkin et al34 have shown that thalidomide should be limited to fewer than 6 months to minimize the risk of neurotoxicity. In our trial, the incidence of severe neuropathy (grade 3–4) was acceptable (4%). Nine percent of patients had to discontinue thalidomide because of drug-related adverse events, and peripheral neuropathy was the main reason for discontinuation. In our study, the dose of maintenance thalidomide was 100 mg/day for a median duration of 6 months.

In contrast, Attal et al23 reported that 39% of patients had to discontinue thalidomide because of drug-related adverse events. In their study, median duration of maintenance thalidomide was 15 months, with a mean dose of 200 mg/day.

Stewart et al35 reported that the adverse effects of thalidomide, when used as maintenance therapy after transplantation, were dose related. Others studies in the posttransplantation setting have also suggested cumulative effects.36

Because responses may occur with doses of 50 to 100 mg/day,37 maintenance therapy with lower doses should be studied. Our results suggest that the use of low-dose thalidomide (100 mg/day) for maintenance after ASCT is an active treatment approach with acceptable toxicity and improved survival.

In conclusion, up-front single ASCT followed by 6 months of maintenance therapy with thalidomide (with second ASCT in reserve for relapse or progression) is an effective therapeutic strategy to treat MM patients and appears superior to tandem transplantation in this setting.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Jean-Luc Harousseau for his critical reading of the manuscript. We are indebted to the patients who participated in the trial, to the attending physicians who referred their patients to our center, and to Mr Naceur Gharbi for his support.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Research (03/UR/08-03) and the Association Tunisienne des Greffés de la Moelle Osseuse (ATGMO).

Authorship

Contributions: A.A., L.T., T.B.O., S.L., A.L., N.B.R., H.E.O., M.E., H.B., R.J., L.A., H.K., A.B.H., F.M., A.S., M.H., K.B., A.A., H.L., K.D., and A.B.A. participated in designing and performing the research; A.A. analyzed the data and wrote the paper, and all authors checked the final version of the manuscript.

A complete list of the members of the Tumisian Multiple Myeloma Study Group is provided in Document S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Abderrahman Abdelkefi, Centre National de Greffe de Moelle Osseuse, Rue Jebel Lakhdar, 1006 Bab Saadoun, Tunis, Tunisia; e-mail: aabdelkefi@yahoo.fr.