The characteristic chromosomal translocation of follicular lymphoma, the t(14;18)(q32;q21), has also been detected at high prevalence and frequency in circulating B cells in healthy individuals.1-3 Since both the t(14;18) and the t(11;14)(q13;q32) translocations are thought to be generated by a common mechanism at at least one site, the VDJ recombinase,4 we determined the prevalence of t(11;14)–as well as t(14;18)–positive cells in the peripheral blood of 100 healthy individuals by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

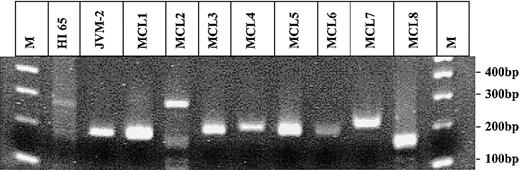

The PCR for the detection of the BCL-2/IgH rearrangement has previously been described.5 The t(11;14) translocation was analyzed using the same JH-consensus primer in combination with a BCL-1 primer 5′-GATAAAGGCGAGGAGCAT-3′ and a BCL-1 probe 5′-TAACCGAATATGCAGTGCAGCAATT-3′. At least 5 replicates of 1 μg DNA isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) were tested for the presence of each translocation. The total number of cells tested was determined by quantitative PCR using k-ras as reference gene. In spiking experiments, a single t(11;14)–positive JVM-2 cell diluted in 250 000 t(11;14)–negative cells could be consistently detected. Circulating t(11;14)–positive cells were detected in only one of the 100 healthy individuals at a frequency of 0.6 t(11;14) copies/105 PBMNCs (Table 1). The translocation fragments amplified from the t(11;14)–positive healthy individual HI65, from the JVM-2 cell line, and from all t(11;14)–PCR–positive patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) ever tested in our laboratory were sequenced. All nucleotide sequences showed a unique and distinct combination of BCL-1 breakpoint, N-nucleotides, and JH breakpoint (Table 2). The sequence analysis failed in one patient (MCL8). However, the length of the t(11;14) fragment, of about 180 bp, amplified from this patient compared with the one of the healthy individual HI65, of 281 bp (Figure 1), makes a false-positive result due to contamination very unlikely. PBMNC samples of the t(11;14)–positive healthy individual (HI65) obtained 2 years before and 3 years after the t(11;14)–positive sample were negative by t(11;14)–PCR.

Agarose-gel electrophoresis of all t(11;14) PCR fragments amplified in this study and ever in our laboratory. Gel electrophoresis of all t(11;14) fragments amplified by PCR. Lanes 1 and 12: 100 bp molecular weight marker (M); lane 2: HI 65; lane 3: JVM-2; lanes 4-11: MCL1-8.

Agarose-gel electrophoresis of all t(11;14) PCR fragments amplified in this study and ever in our laboratory. Gel electrophoresis of all t(11;14) fragments amplified by PCR. Lanes 1 and 12: 100 bp molecular weight marker (M); lane 2: HI 65; lane 3: JVM-2; lanes 4-11: MCL1-8.

In contrast to the very low prevalence of t(11;14)–positive cells, 39 (45%) of 86 individuals were t(14;18)–positive, comparable to earlier results.1-3

Since the DNA breaks at the IgH locus are mediated in both translocations by the VDJ recombinase, the markedly different prevalence of circulating t(11;14)– and t(14;18)–positive cells in healthy individuals could be explained by different frequencies of DNA breaks occurring within the BCL-1 and the BCL-2 gene. In addition, the clonal expansion of the translocation-carrying cells, which is necessary for detection in the peripheral blood by PCR, may be influenced by variable degrees of proliferative potential of the affected cells and the different susceptibility to immunologic control mechanisms. Moreover, the acquisition of the t(14;18) translocation may be regarded as the first step in the development of follicular lymphoma,6 whereas in mantle cell lymphoma there is some evidence that the t(11;14) translocation might be preceded by alterations affecting the genomic stability, such as mutations or deletions of the ATM gene.7,8 If an impaired genomic stability is a prerequisite for the formation of the t(11;14) translocation, the prevalence of t(11;14)–positive cells in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals would be expected to be very low.