Abstract

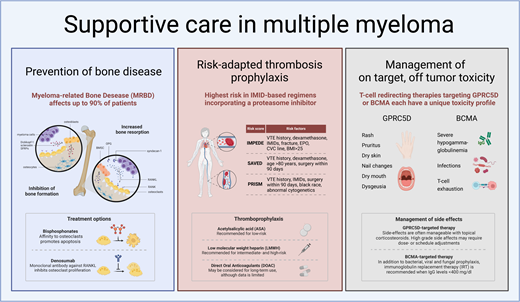

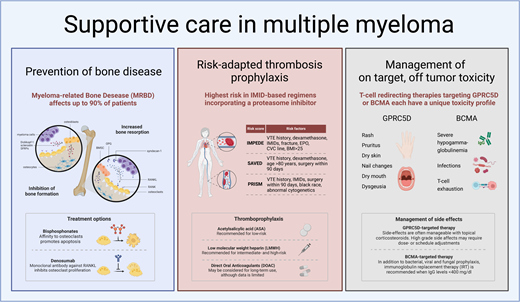

The overall survival in patients with multiple myeloma has increased over recent decades. This trend is anticipated to further advance with the emergence of T-cell–redirecting therapies, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapy and T-cell–engaging bispecific antibodies. Despite these therapeutic improvements, treatment-related adverse events impede quality of life. This underscores the imperative of optimizing supportive care strategies to maximize treatment outcomes. Such optimization is crucial not only for patient well-being but also for treatment adherence, which may translate into long-term disease control. We here describe a) how to prevent bone disease, b) a risk-adapted thrombosis prophylaxis approach, c) the management of on-target, off-tumor toxicity of G-protein–coupled receptor class C group 5 member D-targeting T-cell–redirecting therapies, and d) infectious prophylaxis, with a focus on infections during T-cell–redirecting therapies

Learning Objectives

Reduce the risk of skeletal-related events

Identify patients at high risk of thrombosis and apply risk-adapted thrombosis prophylaxis

Optimize T-cell–redirecting therapy

Prevent infections

CLINICAL CASE

In September 2021, a 57-year-old woman with triple-class refractory multiple myeloma (MM) was referred to our hospital to discuss treatment options. She was diagnosed with immunoglobulin G kappa (IgG-κ) MM in 2015 (International Staging System 2, standard-risk cytogenetics) while presenting with anemia and multiple osteolytic bone lesions. She was initially treated in the Carthadex trial, consisting of induction therapy with carfilzomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone (KTd), followed by an autologous stem cell transplant (auSCT) and consolidation therapy with KTd.1 During the first cycle of KTd, she developed deep venous thrombosis despite prophylaxis with aspirin, for which a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) was started and discontinued at the time of the auSCT. Thirty months after auSCT, she experienced disease progression, and from 2018 until 2021, she was subsequently treated with ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone, daratumumab-bortezomib-dexamethasone, and pomalidomide-cyclophosphamide-prednisone.

After extensive discussion, she was enrolled in a phase 1/2 study, and treatment with daratumumab plus talquetamab was started (talquetamab 400 µg/kg/wk, daratumumab according to the standard administration scheme). During the first cycle of talquetamab, she developed an itchy skin rash covering less than 30% of her body (grade 2), which disappeared following the application of topical corticosteroids. Subsequently, an unpleasant taste (dysgeusia grade 2) and xerostomia (grade 1) occurred, leading to a loss of appetite and less food intake. In the second cycle, the skin of her hands started to peel off, and she developed brittle nails. Although these adverse events were classified as limited severity according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events classification, they impaired her quality of life (QoL). Therefore, it was decided to decrease the dose frequency (after cycle 9, biweekly; after cycle 14, monthly; and, finally, from cycle 39 onward, every 2 months), after which the side effects disappeared, and she experienced a very good QoL. She achieved complete remission after 4 months of treatment, which still persists.

Introduction

The introduction of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs; thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide), proteasome inhibitors (PIs; bortezomib, ixazomib, and carfilzomib), and monoclonal antibodies (daratumumab and isatuximab targeting CD38 and elotuzumab targeting SLAMF7) has significantly enhanced overall survival (OS) in patients with MM over recent decades. This trend is anticipated to further advance with the emergence of T-cell–redirecting therapies, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy and T-cell–engaging bispecific antibodies (BsAbs). However, despite these therapeutic advancements, achieving a concomitant improvement in QoL has not been universally realized, with many clinical trials merely indicating the absence of QoL deterioration, especially in the relapsed/refractory setting. Encouragingly, recent reports have documented substantial QoL enhancements following anti–B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) CAR T-cell therapy compared to standard-of-care therapies.2 Given that disease control typically correlates with reduced symptomatology, treatment-related adverse effects likely impede QoL, as exemplified in the presented clinical case. This underscores the imperative of optimizing supportive care strategies to maximize treatment outcomes. Such optimization is crucial not only for patient well-being but also for treatment adherence to sustain long-term disease control.

Prevention of bone disease

Myeloma-related bone disease (MRBD) affects up to 80% of newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) patients and up to 90% of patients during the course of the disease. Patients are at high risk of developing skeletal related events (SRE), such as pathological fractures or spinal cord or nerve root compression, frequently necessitating radiotherapy or even surgical intervention.3 Bone disease negatively affects QoL and functional capacity.

Under physiological conditions there is a homeostasis between bone resorption and formation in which osteocytes play a leading role. Osteocytes account for most of the cells found in mature mineralized bone and coordinate bone maintenance through interactions between osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Bone microdamage results in the apoptosis of osteocytes, which leads to the release of paracrine factors that increase local angiogenesis and recruitment of osteoclast and osteoblast precursors. Osteoclasts adhere to the bone surface, dissolve the bone mineral, and degrade the collagen-rich bone matrix. Following resorption, osteoblasts secrete type 1 collagen-rich osteoid matrix and regulate osteoid mineralization. The two key signaling pathways in bone remodeling are the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) interacting with RANK and the RANKL decoy receptor osteoprotegerin (OPG) and the Wnt signaling pathway. RANKL/RANK interaction leads to osteoclast differentiation and activation. Wnt signaling induces osteoblast proliferation and differentiation, leading to bone formation. In addition, it activates OPG production by osteoblasts, which antagonizes the interaction between RANKL and RANK on osteoclasts, thereby inhibiting osteoclast maturation and activation. In quiescent bone, osteocyte expression of the Wnt inhibitors sclerostin and DKK1/2 prevents bone formation, whereas during the bone remodeling cycle osteocyte expression of the Wnt-inhibitors declines, permitting bone formation by osteoblasts after bone resorption. In MRBD this homeostasis is disturbed by the interaction of malignant plasma cells with all bone cells. An important cause of an increase in bone destruction is the fact that syndecan-1 mediated myeloma cell binding to OPG leads to the inactivation of OPG, which is the RANKL soluble decoy receptor. This results in an increased RANKL/OPG ratio, leading to the activation of osteoclasts. In addition, MM-induced osteocyte cell death and the adhesion of MM cells to bone marrow stromal cells activates RANKL production by osteocytes, bone marrow stromal cells, and to a lesser extent MM cells, directly binding to RANK on osteoclast precursors, promoting osteoclastogenesis. Importantly, in addition to an increase in bone destruction, bone formation is also inhibited as both malignant plasma cells and osteocytes produce the Wnt antagonist sclerostin, Dickkopf-1, and soluble frizzled-related proteins. This causes a decrease in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation.4

Current strategies for MRBD prevention and treatment primarily focus on inhibiting osteoclast activity using bisphosphonates, as specific methods for activating osteoblasts remain unavailable. However, PIs, by inhibiting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, may exert direct anabolic effects on bone by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and enhancing the differentiation of osteoblasts from mesenchymal cells.5,6 Bisphosphonates, which are pyrophosphate analogues, bind to hydroxyapatite crystals during bone remodeling. This binding leads to the endocytosis of bisphosphonates by osteoclasts, resulting in their apoptosis. Additionally, denosumab, a monoclonal IgG2 antibody against RANKL, is introduced. Denosumab mimics OPG by inhibiting the interaction between RANKL and RANK, thereby preventing osteoclast activation and maturation.3

There have been 20 randomized trials comparing bisphosphonates with either placebo or no treatment. Only 4 trials have directly compared different bisphosphonates, and 1 trial has compared zoledronate with denosumab, as summarized in Table 1. These trials were reviewed in a Cochrane meta-analysis.3,7 Based on these trials and expert opinions, the Bone Disease Working Group of the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) has recently published guidelines for the optimal treatment of bone disease (Table 2).3 The IMWG recommends bisphosphonate treatment for all patients with MM, regardless of the presence of bone disease, due to a lower incidence of pathological fractures, skeletal-related events (SREs), and pain compared to placebo or no treatment. Zoledronate is preferred, having demonstrated superiority over oral clodronate in OS in a direct comparison. Additionally, a meta-network analysis indicated superior OS with zoledronate compared to etidronate and placebo. Furthermore, zoledronate was found to more effectively reverse hypercalcemia compared to pamidronate in a pooled analysis of 2 randomized trials.3 Denosumab is an alternative for zoledronate and proven to be noninferior to zoledronate with respect to SREs.8 Importantly, the incidence of renal toxicity is lower with denosumab, and denosumab can also be administered in case of renal failure, whereas a creatinine clearance of equal to or greater than 35 and 30 mL/min is required for zoledronate and pamidronate therapy, respectively.

There is no robust evidence guiding the optimal dose frequency and duration of bisphosphonate therapy. In the MRC Myeloma IX trial, zoledronate was administered monthly. A randomized clinical trial comparing zoledronate administration every 4 weeks vs every 12 weeks, which included 1822 patients (278 of whom had MM), demonstrated noninferiority of the 12-week interval with respect to SREs, including in the MM subgroup. This suggests that administering zoledronate every 3 months is safe.9 A follow-up analysis of the MRC Myeloma IX trial showed an OS benefit in patients who received bisphosphonates for 2 years or more, supporting a treatment duration of at least 2 years.10

Clinical trials for MRBD have only investigated the continuous monthly administration of denosumab. In osteoporosis treatment, the discontinuation of denosumab has been associated with rebound osteoclastogenesis, a rapid decrease in bone mineral density, and an increased risk of vertebral fractures. This rebound effect can be mitigated by a single dose of zoledronate administered 6 months after discontinuing denosumab. The IMWG advises this approach, although specific data in MM patients are lacking.3,11

Although osteoblast formation is decreased, bone formation is possible in MM patients.12,13 Therefore, calcium and vitamin D supplementation should be administered to all patients receiving bisphosphonates, as vitamin D is essential for calcium uptake and bone formation, and vitamin D deficiency is common in MM patients.3

Thromboprophylaxis in MM

MM is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), which is further heightened during anti-MM therapy, particularly with IMiDs.14 Consequently, the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) guidelines recommended employing risk-adapted thromboprophylaxis for all patients undergoing therapy, advocating aspirin for those at low risk and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for those at high risk.15,16 However, despite the adoption of these preventive measures, the incidence of VTE remains elevated, possibly due to the oversight of patient- and disease-related factors in routine practice, leading to underestimated thrombosis risk. Furthermore, the guidelines were formulated in an era of mainly single or double therapies, whereas the treatment landscape has since evolved, with triple and quadruple therapy and prolonged IMiD use applied in the majority of patients. This is evidenced by recent findings from the Griffin trial reporting VTE rates of 10% with daratumumab-bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexametasone and 15% with bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexametasone, despite aspirin prophylaxis.17 In the IFM/DFCI 2009 trial in which prophylaxis with LMWH was used, 4.8% of patients developed VTE during the first 6 months of treatment, using bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone as induction therapy.18 Additionally, a study conducted in a single-center population comprising nearly 700 NDMM patients revealed a persistently high VTE risk despite prophylaxis, with aspirin being the predominant prophylactic agent. During the first year after diagnosis 12.4% experienced VTE, of which 75% occurred in the first 6 months of treatment. Treatment with carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone posed the highest risk (21.1%), followed by quadruple induction therapy (11.1%).19 Accordingly, a systematic review encompassing almost 10 000 patients highlighted a substantial risk of thrombosis despite thromboprophylaxis, confirming the highest risk with lenalidomide-based regimens incorporating a PI (1.3; 95% CI 0.7-2.3] events per 100 patient-cycles).20

These observations prompt several questions. First, can we refine risk stratification by optimizing the incorporation of treatment-related risk factors and by further refining the assessment of patient-related risks? Second, is there merit in considering the adoption of DOACs? DOACs offer efficacy along with the convenience of oral administration, potentially presenting a viable option for thromboprophylaxis in MM patients.

Three-risk assessment tools have been developed derived from retrospective analyses of extensive data sets comprising NDMM patients: the SAVED, IMPEDE-VTE, and PRISM scores (Table 3).21-23 Each score has its limitations. First, the SAVED score only included individuals aged over 65 years. Second, both the SAVED and IMPEDE-VTE scores were formulated based on data sets including approximately 25% of patients receiving more than 160 mg of dexamethasone per month, a dose no longer employed in clinical practice due to its adverse impact on survival.24 Third, the PRISM score incorporates abnormal metaphase cytogenetic analysis, which is currently being replaced by novel molecular assays. Notably, none of the cohorts included patients treated with carfilzomib or daratumumab. Nevertheless, despite these considerations and the fact that validation in large data sets is needed (particularly in the context of triplet and quadruplet regimens for induction therapy and long-term maintenance treatment), these tools can aid in assessing VTE risk and inform decisions regarding anticoagulation strategies for individual patients in clinical practice.

Based on the increased incidence of thrombosis in intermediate- and high-risk patients as indicated by the 3 novel risk-stratification tools, thromboprophylaxis with LMWH instead of aspirin is recommended. Despite solid evidence, it is advised to continue treatment for at least 6 months after diagnosis/start of treatment, during which the incidence of VTE is highest.

DOACs can also be considered, especially for long-term use, although data are still limited. The safety of apixaban has been demonstrated in a small phase 4 trial and a prospective phase 2 trial.25,26 In a retrospective series of 305 patients, rivaroxaban appeared to reduce the risk of thrombosis in patients treated with carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone compared to those treated with aspirin (4.8% vs 16.1%, respectively). The incidence observed with rivaroxaban was comparable to patients treated with bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone, who received aspirin as thromboprophylaxis. This indicates the higher incidence of VTE with carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone, which can be reduced by rivaroxaban, but not with aspirin.27 Further randomized controlled trials are needed to investigate the efficacy of DOACs in this context.

Management of on-target, off-tumor toxicity of GPRC5D-targeting T-cell–redirecting therapies

Skin- and oral adverse events with GPRC5D-targeting T-cell–redirecting therapy

G protein–coupled receptor class C group 5 member D (GPRC5D) is encoded by the GPRC5D gene on chromosome 12p and is a transmembrane receptor predominantly expressed on MM cells compared to normal plasma cells and other immune cell subsets. GPRC5D is also expressed in keratinized tissues, such as hair follicles and nails, as well as in the filiform papillae of the tongue. This expression profile can result in on-target, off-tumor effects, manifesting as dry skin, exfoliation, erythema, rash, brittle nails, onycholysis, dysgeusia, dry mouth, and dysphagia.28,29

Current data suggest that GPRC5D-targeting CAR T-cell therapies exhibit fewer on-target, off-tumor side effects compared to GPRC5D-targeting BsAbs such as talquetamab and forimtamig, though the follow-up periods of phase 1/2 CAR T-cell studies remain limited (Tables 4 and 5). This lower incidence may be attributable to single vs continuous administration and differences in the specific epitope targeted.30-34

With the GPRC5D-targeting BsAbs, skin-related side effects such as rash and desquamation typically occur early (3-4 weeks after treatment initiation). These manifestations are mainly grade 1 or 2 toxicities, occurring in up to approximately 80% of patients, with a rash of grade 3 or higher occurring in up to approximately 15%.29-31,35 In contrast, GPRC5D-targeting CAR T-cell therapies have reported grade 1 to 2 skin toxicities in only approximately 20% of patients, primarily presenting as rash (Tables 4 and 5).

The management of skin-related side effects includes the use of topical corticosteroids, moisturizing creams, and oral antihistamines for pruritus. Early intervention with a short course of oral corticosteroids may prevent rash exacerbation. Most patients can continue BsAb therapy without dose or schedule adjustments, although therapy should be withheld in cases of toxicity of grade 3 or higher (extensive surface involvement, dryness, peeling, blistering with pruritus/pain affecting daily activities). This only occurred in 1% of talquetamab-treated patients. Talquetamab could be resumed at a lower dose or reduced-dose intensity upon resolution of the adverse event.30

Nail-related side effects, including discoloration, dystrophy, hypertrophy, ridging, onycholysis, and onychomadesis, were generally grade 1 or 2 and occurred after approximately 2 months. Incidence rates varied, likely due to differences in follow-up and therefore drug exposure across CAR-T and BsAb studies (Tables 4 and 5). For instance, the MonumenTAL-1 study showed an increase in nail-related changes from 27% to 43% in the 800 µg/kg biweekly cohort with longer follow-up.29,30 Moreover, there is a lack of standardized definitions and grouping of nail-related side effects explaining differences in incidences. This highlights the urgent need for standardization and proper reporting.29-34

Nail-related side effects often resolve without intervention. Several measures have been reported based on the personal experience of treating physicians and patients' experiences, such as the application of emollients, nail hardeners, vitamin E oil, and protective nail coverings.

Oral- and gastrointestinal-related side effects, such as dysgeusia, dry mouth, dysphagia, decreased appetite in general, and weight loss occurred early, with a median onset after 2 to 4 weeks following treatment, and were mostly grade 1 to 2 (Tables 4 and 5). It is important to realize that the maximum toxicity grade of dysgeusia is grade 2 in the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5 scaling, being defined as altered taste with change in diet (eg, oral supplements, noxious or unpleasant taste, loss of taste). The impact of dysgeusia on global QoL and oral QoL was investigated in a small number of patients approximately 2 months after starting talquetamab. Notably, there was a pronounced and significant decrease in the total taste score, as measured with Burghart taste strips, with all patients experiencing hypogeusia. This translated into a significant decrease in global QoL and oral QoL, the latter being caused by “dry mouth, different taste of food and drinks, problems eating solid food and sensitive mouth.” Importantly, saliva production was not reduced, indicating that stimulating salivary flow is not a viable solution for these complaints.36

In summary, on-target, off-tumor skin-related and oral side effects are common but manageable, not requiring discontinuation of therapy. This is corroborated by the low discontinuation rates (∼5%) in phase 1/2 studies with talquetamab and forimtamig.30,31 However, it is important to note that phase 1/2 study participants are highly motivated, potentially leading to higher tolerance of side effects. Persistent low-grade toxicity can negatively impact QoL, underscoring the need for better supportive care.37,38 As supportive care measures are limited, especially for oral- and nail-related side effects, there is an urgent need for exploring different dosing schedules. An approach to minimize toxicity while preserving efficacy includes the strategy of decreasing either the dose of talquetamab or the frequency of administration. Although only prospectively investigated in 19 patients in a nonrandomized way and still with short follow-up, a trend in improvement of skin toxicity, nail toxicity, and oral toxicity was observed as compared to patients in whom the dose was not reduced. However, reduced oral did not (yet) translate in a concomitant decrease in weight loss.39 The TALISMAN study will investigate prophylactic interventions to prevent and/or limit severity of talquetamab-related oral toxicities.

Infectious prophylaxis, with a focus on infections during T-cell–directing therapies

General aspects

Infections are common in patients with MM, with a 7-fold increase in bacterial infections and a 10-fold increase in viral infections reported in a large observational study of almost 10 000 patients with MM, compared to almost 35 000 age-matched and sex-matched controls. Infections result in pronounced morbidity and mortality.40 The high incidence of infections is explained by the negative impact of MM on the immune system itself, combined with the immunosuppressive effects of anti-MM treatment. For an extensive review on the background and the need for prophylaxis during treatment with non–T-cell–directing therapies, we refer to the IMWG guidelines and the vaccination guidelines of the European Myeloma Network.41,42

The benefit of prophylactic immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IGRT) in MM patients is largely unknown as evidence comes from only 1 randomized clinical trial, showing protection against severe and recurrent infections.43 A systematic review suggests a reduction in bacterial infections; however, there is no demonstrated survival advantage.44 The added value may be more pronounced in this era of novel agents. CD38 antibodies as monotherapy result in a rapid decrease in polyclonal IgA levels, although polyclonal IgG levels remain stable. But it is known that potent triplet or quadruplet regimens, including those incorporating CD38 antibodies, are associated with the development of hypogammaglobulinemia (HGG), most likely because of the synergistic elimination of both malignant and normal plasma cells.45,46 On the other hand, the randomized controlled trial, investigating the value of IGRT, was performed before the more frequent use and more effective antibacterial prophylaxis and vaccination strategies, which may decrease the benefit of IGRT. Therefore, a more restrictive use of IGRT has been advised by the IMWG, limiting replacement therapy to patients with serum IgG concentrations of less than 400 mg/dL who have severe and recurrent infections by encapsulated bacteria despite appropriate antimicrobial prophylaxis and vaccination.42

However, for patients undergoing T-cell–redirecting therapies, particularly those targeting BCMA, and specifically among those receiving BsAbs, additional measures are necessary to mitigate the risk of infections, including the use of IGRT as primary prophylaxis (see Table 6 and next section).

Specific infectious prophylactic measures during therapy with T-cell–redirecting therapies

BCMA, also known as tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 17, is encoded by the TNFRSF17 gene on chromosome 16p. This type III transmembrane protein belongs to the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily.47 BCMA is highly expressed on malignant plasma cells, as well as on a subset of mature normal B cells and normal plasma cells. Consequently, severe HGG is observed following treatment with BsAbs targeting BCMA. This effect is more pronounced than with GPRC5D-targeting BsAbs, which spare normal B cells.28,48-50 The differential impact on normal immune cells explains the higher rate of infections in patients treated with BCMA-targeting BsAbs, compared to those receiving non–BCMA-targeting T-cell–redirecting therapies, which has been documented both in clinical trials and real-world data (Table 6). Additionally, T-cell exhaustion during BsAb therapy, which occurs independently of the tumor target, contributes to the increased incidence of infections, including opportunistic infections such as Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP) and clinically significant cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation, compared to non–T-cell–redirecting therapies. However, it is important to note that direct head-to-head comparisons are lacking.30,31,51-58

Early studies involving BsAbs have consistently shown a high incidence of infections (Table 7A). The MajesTEC-1 study, the largest series investigating the BCMA-targeting BsAb teclistamab with the longest follow-up, showed an overall infection rate of 80% and a 55.2% rate of grade 3 to 5 infections. Notably, 12.7% of patients died due to infection, mainly due to COVID-19. Viral infections occurred in 12.1% of patients, both primary respiratory viruses as well as the reactivation of herpesviruses, CMV, and Epstein-Barr virus. COVID-19 occurred in 29.1% of patients. There was a 5.5% incidence of fungal infections, mainly candida, and an additional 4.2% of PJP (Table 7B).30,54

The largest real-world series with 229 patients, of whom 67% received teclistamab, 20% elranatamab, and 13% talquetamab, reported infections of grade 3 or higher at a rate of 53%, predominantly respiratory tract infections (50%) and bacteremia (15%). Patients were followed for infections from the end of the first priming dose until 3 months after interruption of the treatment. Admission to the hospital was required in 56% of infectious events. In 13% admission to intensive care was required, and 9% died of infections. Importantly, infectious events led to the discontinuation of therapy in 13% of patients and a delay or dose adjustment in 31% of patients. The all-grade infection rate was higher in BCMA-targeting BsAb (73%) as compared to talquetamab (51%).56 A recent worldwide real-world World Health Organization pharmacovigilance database confirmed the higher incidence of infections with the BCMA-targeting BsAb teclistamab, as compared to all other anti-MM treatments (reporting odds ratio [ROR], 1.9 [1.6–2.3]), non–BCMA-targeting BsAbs (ROR, 2.1 [1.1–4.1]), and anti-BCMA CAR-T cells (ROR, 2.8 [2.1–3.7], whereas there was no difference with elranatamab (ROR, 1.1 [0.6–1.8]).57

With CAR T-cell therapy the incidence of overall infections ranged from 42% to 69% in 4 major clinical trials, with grade 3 to 4 infections occurring in 6% to 28% of patients (Table 8A). In the randomized KarMMa-3 and Cartitude-4 studies, which compared BCMA CAR T-cell therapy with standard-of-care regimens, the overall incidence of infections was approximately 60% and severe infections, approximately 25%, comparable to what was observed in the standard-of-care arms.60,61 Similar data were observed in real-world retrospective studies (Table 8B). The majority of infections occurred more than 30 days after the administration of CAR-T cells. Bacterial (mainly respiratory) and viral infections were evenly distributed between days 31 and 100, and viral infections predominated after day 100.59 Recently, the Immune Effector Cell-Associated HematoToxicity (ICAHT) grading system was developed, defining early (day 0-30) and late (day 30+) cytopenia and a grade based on the depth of neutropenia.62 Severe ICAHT was associated with a higher rate of severe infections, increased nonrelapse mortality, and inferior survival outcomes.63 The risk for developing severe ICAHT can be determined by the CAR-HEMATOTOX score before the initiation of lymphodepletion and incorporates the complete blood count and the inflammatory markers C-reactive protein granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and ferritin.64 Because of its predictive value, algorithms for the use of prophylactic granulocyte colony-stimulating factor have been developed, based on the ICATH and CAR-HEMATOTOX scores.62

Due to the significant infectious risk associated with T-cell– redirecting therapies, additional screening and preventive measures, alongside antibiotic and antiviral prophylaxis, are recommended (Table 6). However, it should be noted that the efficacy of several recommendations remains uncertain. This uncertainty primarily pertains to the impact of HGG and the potential benefits of IGRT in mitigating infection risk. Data on IGRT in BCMA-targeting BsAb-treated patients is primarily retrospective. In a small series of 39 patients, 100% experienced profound HGG, with a median onset time of 2.6 months. The infection rate was 3.3 per patient-year, with grade 3 to 5 infections occurring at a rate of 0.7 per patient-year. The estimated median time to first any-grade infection was 3.8 months, while the estimated median time to first grade 3 to 5 infection was 18.7 months. The infection risk remained elevated over time. Nearly all patients received IGRT at some point during the study, being “on IGRT” for 56% of the study duration. IGRT reduced the infection rate by 90%.65 Accordingly, a series of 52 patients demonstrated the protective effect of IGRT. Among these patients, 20 received primary prophylaxis, while 32 received secondary prophylaxis (initiated after a first infection). The incidence rate of infections was significantly lower in patients receiving primary prophylaxis compared to those not on IGRT (0.12 vs 13.6 per patient-year). Additionally, patients who received IGRT as secondary prophylaxis also exhibited a lower incidence rate of infections (0.083 per patient-year), compared to no IGRT.50 In conclusion, retrospective data, which may be subject to bias, show that IGRT strongly reduces infectious complications. Therefore, the guidelines of the IMWG advise to use IGRT as primary prophylaxis starting as soon as IgG levels are less than 400 mg/dL.29 Ideally, randomized studies will investigate the added value of primary vs secondary prophylaxis. Moreover, reducing dose frequency or adopting a fixed-duration therapy of BsAbs may be beneficial, as preliminary data suggest that switching from weekly to biweekly dosing of BCMA-targeted BsAb therapy reduces infections.54

Conclusions

MM-related symptoms and treatment-induced toxicities require supportive care in addition to anti-MM treatment, in order to optimize the well-being of patients. MRBD is one of the most devastating symptoms for patients. Future work should focus on elucidating the pathophysiology of myeloma-induced inhibition on osteoblastogenesis in order to introduce bone-formation strategies to further improve bone health. Thrombosis incidence is still high. Hopefully, DOACs will show improved efficacy alongside better tolerability than aspirin and LWMH in future trials. The highly effective T-cell–redirecting therapies, associated with unique side effects, such as oral and skin abnormalities and infections, especially with long-term use, require specific supportive care measures to guarantee safe use and improve QoL.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Sonja Zweegman: research funding: Celgene, Takeda, Janssen Pharmaceuticals; advisory board: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, Celgene, Takeda, Amgen, Oncopeptides.

Niels W.C.J. van de Donk: research funding: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Celgene, Novartis, Cellectis, Bristol Myers Squibb; advisory board: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Takeda, Roche, Novartis, Bayer, Pfizer, Abbvie, Adaptive, Servier.

Off-label drug use

Sonja Zweegman: There is nothing to disclose.

Niels W. C. J. van de Donk: There is nothing to disclose.