Abstract

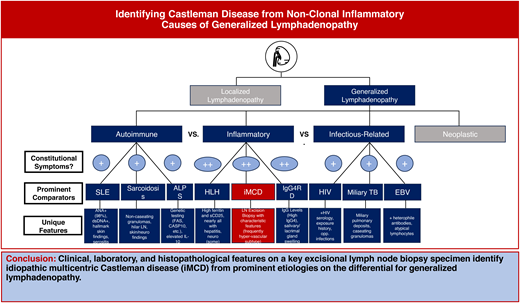

Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD) is a rare, life-threatening subtype of Castleman disease (CD), which describes a group of rare, polyclonal lymphoproliferative disorders that demonstrate characteristic histopathology and variable symptomatology. iMCD involves a cytokine storm that occurs due to an unknown cause. Rapid diagnosis is required to initiate appropriate, potentially life-saving therapy, but diagnosis is challenging and impeded by clinical overlap with a wide spectrum of inflammatory, neoplastic, and infectious causes of generalized lymphadenopathy. Diagnosis, which requires both consistent histopathologic and clinical criteria, can be further delayed in the absence of close collaboration between clinicians and pathologists. A multimodal assessment is necessary to effectively discriminate iMCD from overlapping diseases. In this review, we discuss a pragmatic approach to generalized lymphadenopathy and clinical, laboratory, and histopathological features that can aid with identifying iMCD. We discuss diagnostic barriers that impede appropriate recognition of disease features, diagnostic criteria, and evidence-based treatment recommendations that should be initiated immediately following diagnosis.

Learning Objectives

Identify patterns in clinicopathologic presentation that differentiate Castleman disease from other non-clonal lymphadenopathies

Understand the limitations of varying lymph node biopsy techniques and apply a risk-benefit assessment influenced by the differential

Introduction

Generalized lymphadenopathy, which can often co-occur with constitutional symptoms, is a significant diagnostic challenge due to the breadth of clinically overlapping neoplastic, inflammatory, autoimmune, and infectious disorders. Beyond “must-not-miss” neoplastic pathologies, other prominent diseases on this broad differential are characterized by high morbidity and mortality, requiring timely therapeutic intervention. Specifically, Castleman disease (CD)—a group of rare, lymphoproliferative diseases united by characteristic histopathology—constitutes an often-overlooked inflammatory cause of lymphadenopathy, where a protracted diagnostic odyssey is common, and patient outcomes can significantly depend on prompt initiation of appropriate therapy.1-3 One of its most aggressive subtypes—idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD)—is clinically characterized by generalized lymphadenopathy, systemic inflammation, and life-threatening multisystem organ dysfunction due to a cytokine storm often involving interleukin-6 (IL-6).2,3

While rapid diagnosis can reduce the significant risk of morbidity and mortality associated with some subtypes of iMCD, accurate diagnosis is challenging given a broad differential and the need for a comprehensive workup, including an excisional lymph node biopsy. Even when a sufficient biopsy is performed, there can be significant discrepancies between pathologists in diagnosing iMCD due to the absence of objective biomarkers.3 Additionally, due to nonspecific clinical features and requisite histopathological criteria, close collaboration between clinicians and pathologists is necessary to discriminate iMCD from other close mimics. This review focuses on the identification of MCD subtypes, from a broader differential of generalized lymphadenopathy, by reconciling clinical, laboratory, and histopathological patterns. We also briefly discuss initiation of evidence-based treatment of iMCD following diagnosis.

CLINICAL CASE

A 36-year-old woman presented to the emergency department 2 weeks after developing nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, progressive fatigue, and severe weight loss. Imaging was notable for hepatomegaly and findings suggestive of acute cholecystitis, for which the patient received a cholecystectomy prior to discharge. The patient immediately re-presented with severe abdominal pain, with additional diagnostic workup revealing an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP; 239.4 mg/L), anemia (Hgb: 10.0 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (101 k/uL), hypoalbuminemia (2.1 g/dL), ascites, pleural effusions, and bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. During a prolonged, monthlong admission, the patient developed diffuse lymphadenopathy, fevers, new-onset splenomegaly, and acute renal failure.

Initial evaluation of generalized lymphadenopathy with constitutional symptoms

The first step of focusing a differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy is to determine if the distribution of enlarged lymph nodes (LNs) is localized or generalized. For the patient presenting with generalized lymphadenopathy, the differential primarily spans a host of neoplastic, infectious, autoimmune, and inflammatory diseases (Table 1). Notably, of the diseases that can present with generalized lymphadenopathy, many are often accompanied by constitutional symptoms, such as low-grade fever, night sweats, and anorexia/weight loss at initial presentation.1,4-6 Though these signs and symptoms are not specific, degree and timing can aid with differentiating between broader disease categories. For example, high-grade fever (>38 °C) would be more commonly associated with infectious pathologies, and acute/hyper-acute onset may be more consistent with an infectious or iatrogenic cause.4 While these features can be suggestive, key questions on history directed at co-occurring pathognomonic clinical symptoms are also helpful. For example, co-occurring rash and joint pain would make rheumatologic and immune-mediated conditions more likely, whereas suspicious wounds, nodules, or exposures (eg, animal contact, undercooked food, environmental exposures) may increase the likelihood of infectious causes. Therefore, in addition to comprehensive assessment of clinical signs and symptoms, generalized lymphadenopathy requires a comprehensive exposure history and drug history. On physical examination, the most significant features to evaluate include lymph node size, consistency, fixation, and tenderness, with red flags for malignancy including diameter >1 cm (2 cm for inguinal nodes), hard consistency, fixation to underlying tissue, absence of tenderness, and supraclavicular LN involvement.4,7 However, some of these concerning physical exam findings can additionally be observed in nonmalignant inflammatory conditions, such as CD and IgG4-related disease (IgG-4RD).8,9

Pragmatic differential diagnosis of generalized lymphadenopathy

| Generalized lymphadenopathy . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory . | Autoimmune . | Infectious . | Neoplastic/clonal . | Miscellaneous/other . |

| iMCD-TAFRO/iMCD-NOS/iMCD-IPL | SLE | Bacterial | BCL | IgG4-RD |

| HLH | ALPS | M. tuberculosis and other Mycobacterium species | TCLs, including AITL | Serum sickness |

| MIS-C/A | RA (majority localized) | Secondary syphilis (early primary is often localized) | Hodgkin lymphoma | Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome |

| Kawasaki disease (children) | SS (majority localized) | Atypical infections† | POEMS and POEMS-MCD | Amyloidosis |

| Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease | sJIA, AOSD | Bacterial sepsis | Metastatic carcinomas | Sarcoidosis |

| Kimura disease | Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) | Lymphogranuloma venereum (Chlamydia trachomatis) | Leukemias (ALL/AML/CML/CLL) | Lipid storage diseases |

| VEXAS syndrome | Chancroid (often localized) | Rosai-Dorfman disease | Chronic granulomatous diseases | |

| Inflammatory pseudotumor | Typhoid fever | Erdheim-Chester disease | Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia | |

| Viral | LCH | Other granulomatous diseases (silicosis, berylliosis) | ||

| HIV | Kaposi's sarcoma | |||

| Acute hepatitis (HBV, HCV) | ||||

| CMV, EBV | ||||

| HHV8 and HHV8-MCD | ||||

| HHV6 | ||||

| HSV | ||||

| Adenovirus | ||||

| Dengue fever | ||||

| Measles, mumps (often localized), and rubella viruses | ||||

| Other | ||||

| Toxoplasma gondii (toxoplasmosis), Leishmania (leishmaniasis) | ||||

| Histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis | ||||

| Generalized lymphadenopathy . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory . | Autoimmune . | Infectious . | Neoplastic/clonal . | Miscellaneous/other . |

| iMCD-TAFRO/iMCD-NOS/iMCD-IPL | SLE | Bacterial | BCL | IgG4-RD |

| HLH | ALPS | M. tuberculosis and other Mycobacterium species | TCLs, including AITL | Serum sickness |

| MIS-C/A | RA (majority localized) | Secondary syphilis (early primary is often localized) | Hodgkin lymphoma | Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome |

| Kawasaki disease (children) | SS (majority localized) | Atypical infections† | POEMS and POEMS-MCD | Amyloidosis |

| Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease | sJIA, AOSD | Bacterial sepsis | Metastatic carcinomas | Sarcoidosis |

| Kimura disease | Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) | Lymphogranuloma venereum (Chlamydia trachomatis) | Leukemias (ALL/AML/CML/CLL) | Lipid storage diseases |

| VEXAS syndrome | Chancroid (often localized) | Rosai-Dorfman disease | Chronic granulomatous diseases | |

| Inflammatory pseudotumor | Typhoid fever | Erdheim-Chester disease | Angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia | |

| Viral | LCH | Other granulomatous diseases (silicosis, berylliosis) | ||

| HIV | Kaposi's sarcoma | |||

| Acute hepatitis (HBV, HCV) | ||||

| CMV, EBV | ||||

| HHV8 and HHV8-MCD | ||||

| HHV6 | ||||

| HSV | ||||

| Adenovirus | ||||

| Dengue fever | ||||

| Measles, mumps (often localized), and rubella viruses | ||||

| Other | ||||

| Toxoplasma gondii (toxoplasmosis), Leishmania (leishmaniasis) | ||||

| Histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis | ||||

Atypical infections: Rickettsia, Leptospira, Bartonella, Brucella (brucellosis), Francisella tularensis (tularemia, often localized), diphtheria (often localized), Yersinia pestis (often localized, buboes), and Ehrlichia.

AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; ALL, acute lymphoid leukemia; ALPS, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AOSD, adult-onset Still's disease; BCL, B-cell lymphoma; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HBV, hepatitis B; HCV, hepatitis C; HHV8, human herpesvirus 8; HHV8-MCD, human herpesvirus 8-associated multicentric Castleman disease; HHV6, human herpesvirus 6; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; HSV, herpes simplex virus; IgG4-RD, immunoglobulin G4-related disease; iMCD-TAFRO/NOS/IPL, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease-TAFRO (thrombocytopenia, anasarca, fever, reticulin fibrosis/renal insufficiency, organomegaly)/NOS (not otherwise specified)/IPL (idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy); LCH, Langerhans cell histiocytosis; MIS-C/A, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; sJIA, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SS, Sjögren's syndrome; TCL, T-cell lymphoma.

Following history and physical examination, we recommend several baseline diagnostic assessments—including a complete blood count (CBC), serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), chest X-ray, HIV testing, and, potentially, LN biopsy, if clinical suspicion for malignancy is high (Table 2)—due to the variable presentation of diagnoses such as blood-based neoplasms, active tuberculosis, and acute HIV infection. Tools such as bedside Doppler ultrasonography of superficial lymphadenopathy can help with evaluating for malignancy by aiding with the identification of red-flag features, such as nodal hypo-echogenicity, presence of avascular areas, displacement of vessels, and peripheral vascularity.4 Meanwhile, nodal matting, soft-tissue edema, and prominent hilar vascularity may be more suggestive of a reactive inflammatory process.4 In addition to the aforementioned steps, other baseline tests should be conducted, including evaluating markers of end-organ damage (eg, creatinine, urinalysis, liver function tests [LFTs]). Further, while CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)—direct and indirect markers of inflammatory processes—are often elevated across several inflammatory conditions and are therefore nonspecific, they can be useful baseline tests, and marked elevations (as in this patient) can make certain pathologies such as iMCD more likely.10-12 A number of additional tests can be performed to evaluate for common etiologies, such as rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) serology, based on clinical suspicion (Table 2); however, ultimately, an excisional diagnostic lymph node biopsy is the gold standard for symptomatic, otherwise unexplained, generalized lymphadenopathy. In addition to baseline diagnostic tests, specialized additional laboratory tests—as a part of infectious, rheumatologic, and inflammatory workups—are a critical part of diagnosis but should be targeted based on symptomatology and clinical suspicion (Table 2).

Initial diagnostic steps for differentiating non-neoplastic causes of generalized lymphadenopathy

| Diagnostic example workup for differential of generalized lymphadenopathy . | ||

|---|---|---|

| All | • CBC • Chest radiograph • HIV-1/2 testing (antigen/antibody combination immunoassay) • SPEP • CRP/ESR | • Assessments of end-organ function (eg, creatinine, urinalysis, LFTs, coagulation studies, albumin) • Variable: US of LN, CT with IV contrast, 18F-FDG PET, LN biopsy (excisional biopsy is the gold standard for CD) |

| Infectious disease differential example workup (if indicated) | • Syphilis: RPR testing (nontreponemal) followed by confirmation with a treponemal test (eg, FTA-ABS) • HBV/HCV: HBV DNA PCR (or HBsAg with anti-HBc IgM antibody confirmation), HCV RNA PCR • EBV: heterophile antibody test (or VCA IgM/IgG [ELISA]) • Other pathogen-specific serology and PCR testing (depending on clinical indication): PCR: CMV (plasma, DNA), HHV8 (plasma, DNA), adenovirus (swab, DNA), HSV (swab/CSF/etc, DNA), HHV6 (plasma/tissue, DNA) ELISA (IgM/IgG): toxoplasmosis (or DNA PCR of tissue/plasma in immunocompromised) • Urine/serum antigen test (Histoplasma, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus) | • Atypical pathogen testing (if clinically indicated): leishmaniasis (DNA PCR), measles (RNA PCR), mumps (RNA PCR), rubella (RNA PCR), dengue (RNA PCR or NS1 antigen testing), Lyme disease (ELISA + Western blot for confirmation), leptospirosis (DNA PCR), brucellosis (DNA PCR), bartonellosis (DNA PCR), tularemia (DNA PCR), diphtheria (toxin PCR), plague (DNA PCR), ehrlichiosis (DNA PCR) • Sputum samples (if clinically indicated) • Blood cultures (with stain request including pathogens of interest) • LN histopathology specific tests (eg, LANA1 for HHV8) |

| Autoimmune differential example workup (if indicated) | • ANA (only if clinically indicated, due to false positives) • Disease-specific antibody testing (eg, anti-dsDNA, anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SS-B, rheumatoid factor, anti-CCP, anti-MPO, anti-PR3 if clinically indicated) • Serum complement levels (eg, C3, C4) • Serum immunoglobulin levels (eg, IgG1-4) • Genetic testing (eg, FAS/FASL/CASP10/NRAS/CASP8 mutations if ALPS is suspected) | • Flow cytometry for immune cell populations (eg, CD4/CD8 T cells in ALPS, if suspected) • Organ-specific imaging evaluation to assess organ involvement (disease specific) • Biopsy of other involved tissue (eg, skin) |

| Inflammatory disease differential example workup (if indicated) | • HLH: ferritin, triglycerides, sCD25, fibrinogen (additional specialized tests and tests to identify the trigger) • Disease-specific inflammatory biomarkers (eg, sIL-2RA, IL-18, CXCL9 for HLH) • Bone marrow examination (disease-specific studies; eg, evidence of hemophagocytosis for HLH) | • LN pathology–specific tests (S100, CD68, CD163, etc) • Serum eosinophils and IgE • Other genetic testing (eg, UBA1 gene sequencing for VEXAS) |

| Diagnostic example workup for differential of generalized lymphadenopathy . | ||

|---|---|---|

| All | • CBC • Chest radiograph • HIV-1/2 testing (antigen/antibody combination immunoassay) • SPEP • CRP/ESR | • Assessments of end-organ function (eg, creatinine, urinalysis, LFTs, coagulation studies, albumin) • Variable: US of LN, CT with IV contrast, 18F-FDG PET, LN biopsy (excisional biopsy is the gold standard for CD) |

| Infectious disease differential example workup (if indicated) | • Syphilis: RPR testing (nontreponemal) followed by confirmation with a treponemal test (eg, FTA-ABS) • HBV/HCV: HBV DNA PCR (or HBsAg with anti-HBc IgM antibody confirmation), HCV RNA PCR • EBV: heterophile antibody test (or VCA IgM/IgG [ELISA]) • Other pathogen-specific serology and PCR testing (depending on clinical indication): PCR: CMV (plasma, DNA), HHV8 (plasma, DNA), adenovirus (swab, DNA), HSV (swab/CSF/etc, DNA), HHV6 (plasma/tissue, DNA) ELISA (IgM/IgG): toxoplasmosis (or DNA PCR of tissue/plasma in immunocompromised) • Urine/serum antigen test (Histoplasma, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus) | • Atypical pathogen testing (if clinically indicated): leishmaniasis (DNA PCR), measles (RNA PCR), mumps (RNA PCR), rubella (RNA PCR), dengue (RNA PCR or NS1 antigen testing), Lyme disease (ELISA + Western blot for confirmation), leptospirosis (DNA PCR), brucellosis (DNA PCR), bartonellosis (DNA PCR), tularemia (DNA PCR), diphtheria (toxin PCR), plague (DNA PCR), ehrlichiosis (DNA PCR) • Sputum samples (if clinically indicated) • Blood cultures (with stain request including pathogens of interest) • LN histopathology specific tests (eg, LANA1 for HHV8) |

| Autoimmune differential example workup (if indicated) | • ANA (only if clinically indicated, due to false positives) • Disease-specific antibody testing (eg, anti-dsDNA, anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SS-B, rheumatoid factor, anti-CCP, anti-MPO, anti-PR3 if clinically indicated) • Serum complement levels (eg, C3, C4) • Serum immunoglobulin levels (eg, IgG1-4) • Genetic testing (eg, FAS/FASL/CASP10/NRAS/CASP8 mutations if ALPS is suspected) | • Flow cytometry for immune cell populations (eg, CD4/CD8 T cells in ALPS, if suspected) • Organ-specific imaging evaluation to assess organ involvement (disease specific) • Biopsy of other involved tissue (eg, skin) |

| Inflammatory disease differential example workup (if indicated) | • HLH: ferritin, triglycerides, sCD25, fibrinogen (additional specialized tests and tests to identify the trigger) • Disease-specific inflammatory biomarkers (eg, sIL-2RA, IL-18, CXCL9 for HLH) • Bone marrow examination (disease-specific studies; eg, evidence of hemophagocytosis for HLH) | • LN pathology–specific tests (S100, CD68, CD163, etc) • Serum eosinophils and IgE • Other genetic testing (eg, UBA1 gene sequencing for VEXAS) |

ALPS, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FASL, FAS ligand; HBV, hepatitis B; HCV, hepatitis C; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; MPO, myeloperoxidase; US, ultrasound; VCA, viral capsid antigen.

In addition to ultrasonography, other imaging modalities can direct diagnostic evaluation and, in the case of computed tomography (CT) scans with IV contrast, are frequently means by which lymphadenopathy is initially detected. During diagnostic evaluation, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) scans can often aid in discriminating malignant lymph nodes based on standardized uptake value, facilitate selection of the most active lymph node for biopsy, and identify bone involvement in histiocytic disorders with overlapping presentation (eg, with symmetric long bone involvement suggestive of Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester disease, while subclinical Rosai-Dorfman bone disease is more readily detected on PET scan).4,13–15 However, the distinction between reactive lymph nodes and inflammatory conditions—including IgG4-RD and other rheumatologic conditions characterized by generalized lymphadenopathy—cannot effectively be made using this methodology.4,16

Recognizing 5 subtypes of MCD

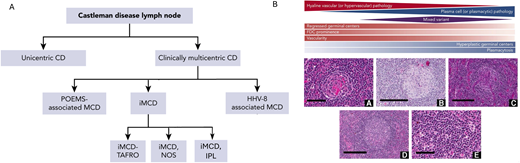

CD is clinically classified as multicentric (MCD) or unicentric (UCD) according to distribution of lymph node enlargement, involving either multiple lymph node regions or a single region, respectively.1 MCD is further defined based on pathogenic mechanisms and treatment approaches, including human herpesvirus 8-associated MCD (HHV8-MCD), POEMS (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal plasma cell disorder, skin changes)-associated MCD (POEMS-MCD), and HHV8-negative/idiopathic MCD or iMCD, where the etiology is unknown.1,2,17

iMCD is further characterized based on clinical findings into 3 subgroups: iMCD-TAFRO (thrombocytopenia, ascites, fever, reticulin fibrosis, renal dysfunction, organomegaly), iMCD-IPL (idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy),18 and iMCD-NOS (not otherwise specified).3 iMCD-TAFRO is the most aggressive form of iMCD and exhibits differences in clinicopathologic features and laboratory abnormalities as well as differences in recommended second-line therapies based on severity.19 In contrast to iMCD-TAFRO patients, iMCD-IPL patients present with thrombocytosis, hypergammaglobulinemia, and a less severe clinical presentation. iMCD-NOS patients do not meet criteria for either iMCD-TAFRO or iMCD-IPL, but the disease tends to behave less aggressively, similar to iMCD-IPL. A wide range of histopathology exists across UCD and all 5 subtypes of MCD: (1) the hyaline vascular subtype (a term used to describe hyaline vascular/hypervascular-like features in UCD)1 or hypervascular subtype (a term used to describe hyaline vascular/hypervascular-like features in MCD), (2) plasmacytic subtype, and (3) a mixed pattern of both. Of note, while there are defined histopathological subtypes, CD pathology exists along a spectrum that can be difficult to distinguish and has unclear clinical implications. The hyaline vascular/hypervascular subtype is characterized by regressed germinal centers, hypervascularity, and prominent follicular dendritic cells (FDCs); whereas the plasmacytic subtype generally exhibits hyperplastic germinal centers as well as significant plasmacytosis. A framework of the 5 subtypes of MCD—POEMS, HHV8-MCD, iMCD-TAFRO, iMCD-NOS, and iMCD-IPL—and the pathological spectrum is included in Figure 1.

Clinical and histopathological spectrum of Castleman disease.1,3 A. Castleman disease (CD) is clinically divided based on LN distribution (multicentric vs unicentric) and etiology (HHV8-associated, POEMS-associated, and idiopathic). Idiopathic MCD (iMCD) is further subdivided based on clinical subtype (TAFRO, NOS, and IPL, which is a recently implicated subtype of NOS). B. CD subtypes are generally distributed across 3 histopathological subtypes: (1) hyaline/hypervascular, (2) plasmacytic, and (3) mixed.

Clinical and histopathological spectrum of Castleman disease.1,3 A. Castleman disease (CD) is clinically divided based on LN distribution (multicentric vs unicentric) and etiology (HHV8-associated, POEMS-associated, and idiopathic). Idiopathic MCD (iMCD) is further subdivided based on clinical subtype (TAFRO, NOS, and IPL, which is a recently implicated subtype of NOS). B. CD subtypes are generally distributed across 3 histopathological subtypes: (1) hyaline/hypervascular, (2) plasmacytic, and (3) mixed.

Recognizing a combination of clinical, histopathological, and laboratory features—through cross talk between clinicians and pathologists—is paramount to making a CD diagnosis due to the nonspecific nature of these features and the broad spectrum of diseases that can mimic each subtype. All 5 MCD subtypes have unique clinical, laboratory, and histopathological features that lend to being considered on distinctive differentials. For example, iMCD-IPL appears much more similarly to IgG4-RD and can even present with elevated IgG4 that can meet criteria for IgG4-RD (>100 IgG4-positive cells/high-powered field, IgG4:IgG ratio >40%).20-21 However, while IgG4-RD must be considered highly on the differential for iMCD-IPL and iMCD-NOS, iMCD-TAFRO patients present much more acutely, similar to patients with sepsis or acute HIV infection. Given that the histopathological changes in MCD are nonspecific and there is significant interpathologist variability in diagnosing MCD, it is important for clinicians and pathologists to collaborate closely and to engage additional clinicians and pathologists while evaluating a potential diagnosis. Clinical,22 laboratory, and histopathological features characteristic of each of the 5 subtypes of MCD, as well as key disease mimics, are summarized in Table 3.

Clinical, laboratory, and histopathological features of subtypes of MCD

| . | MCD subtypes . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | POEMS-MCD . | HHV8-MCD . | iMCD . | ||

| iMCD-TAFRO . | iMCD-IPL . | iMCD-NOS . | |||

| Laboratory assessment | |||||

| CRP | +/++ | ++/+++ | +++ | ++ | +/++ |

| CBC‡ | Mild to moderate anemia, thrombocytosis | Moderate to severe anemia, thrombocytopenia | Moderate to severe anemia, severe thrombocytopenia | Mild to moderate anemia, severe thrombocytosis | Mild to moderate anemia, normal/mild thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis |

| SPEP | Monoclonal paraprotein (small M-spike) | PHGG | Normal or mild PHGG | Severe PHGG | PHGG |

| IgG4 | Normal | Normal | Normal | Frequent in a subset of patients (but serum IgG4:IgG typically lower than IgG4-RD) | Normal |

| LFTs | Mild elevations can be observed | Mild elevations can be observed | Elevated ALP without hyperbilirubinemia and transaminase elevation | Mild elevations can be observed | Mild elevations can be observed |

| Other unique laboratory features | Endocrinopathy (variable: hypogonadism, adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism) | HHV8 infection, often in the setting of HIV infection | Renal insufficiency; elevated IL-6, VEGF (variable) | Renal insufficiency; elevated IL-6, VEGF (variable) | Renal insufficiency; elevated IL-6, VEGF (variable) |

| Clinical presentation | |||||

| Constitutional signs* | +/++ | ++/+++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Primary LN pattern; % with LAD | Generalized; 100% | Generalized; 100% | Generalized; 100% | Generalized; 100% | Generalized; 100% |

| Other key symptoms/ organ involvement | Often associated with osteosclerotic myeloma; defining features: polyneuropathy (required), organomegaly (hepatosplenomegaly), endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy (required), and skin changes; anasarca | Multiple (pulmonary symptoms, hepatosplenomegaly); anasarca | Multiple (hepatosplenomegaly, renal dysfunction, bone marrow reticulin fibrosis); anasarca; adrenal hemorrhages; eruptive cherry hemangiomas | Multiple (pulmonary symptoms, renal dysfunction) | Multiple (pulmonary, renal); additional autoimmune phenomena (autoimmune hemolytic anemia, paraneoplastic pemphigus, immune thrombocytopenia, etc) |

| Exposure history risk | N/A | Increased HIV exposure history | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Key disease mimics | Multiple myeloma, plasmacytoma, lymphoma | HLH, primary effusion lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma | HLH, sepsis, SLE | IgG4-RD | ALPS, Rosai-Dorfman |

| Histopathological features | |||||

| Lymph node histopathology | Plasmacytic with increased monoclonal plasma cells | HHV8 positive plasmablastic proliferation | Hypervascular or mixed subtype with germinal center regression, vascularity, and FDC prominence | Plasmacytic or mixed subtype with germinal center hyperplasia, vascularity, and increased plasma cells; frequently meets criteria for IgG4-RD lymphadenopathy | 3 potential histopathological subtypes (hypervascular, mixed, plasmacytic) |

| Bone marrow biopsy | Clonal plasma cells, megakaryocyte hyperplasia and atypia | HHV8 latent nuclear antigen (LNA) positive plasmablasts | Megakaryocyte hyperplasia, reticulin fibrosis | Hypercellularity, megakaryocytic atypia, and plasmacytosis (nonspecific) | Hypercellularity, megakaryocytic atypia, and plasmacytosis (nonspecific) |

| . | MCD subtypes . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | POEMS-MCD . | HHV8-MCD . | iMCD . | ||

| iMCD-TAFRO . | iMCD-IPL . | iMCD-NOS . | |||

| Laboratory assessment | |||||

| CRP | +/++ | ++/+++ | +++ | ++ | +/++ |

| CBC‡ | Mild to moderate anemia, thrombocytosis | Moderate to severe anemia, thrombocytopenia | Moderate to severe anemia, severe thrombocytopenia | Mild to moderate anemia, severe thrombocytosis | Mild to moderate anemia, normal/mild thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis |

| SPEP | Monoclonal paraprotein (small M-spike) | PHGG | Normal or mild PHGG | Severe PHGG | PHGG |

| IgG4 | Normal | Normal | Normal | Frequent in a subset of patients (but serum IgG4:IgG typically lower than IgG4-RD) | Normal |

| LFTs | Mild elevations can be observed | Mild elevations can be observed | Elevated ALP without hyperbilirubinemia and transaminase elevation | Mild elevations can be observed | Mild elevations can be observed |

| Other unique laboratory features | Endocrinopathy (variable: hypogonadism, adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism) | HHV8 infection, often in the setting of HIV infection | Renal insufficiency; elevated IL-6, VEGF (variable) | Renal insufficiency; elevated IL-6, VEGF (variable) | Renal insufficiency; elevated IL-6, VEGF (variable) |

| Clinical presentation | |||||

| Constitutional signs* | +/++ | ++/+++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Primary LN pattern; % with LAD | Generalized; 100% | Generalized; 100% | Generalized; 100% | Generalized; 100% | Generalized; 100% |

| Other key symptoms/ organ involvement | Often associated with osteosclerotic myeloma; defining features: polyneuropathy (required), organomegaly (hepatosplenomegaly), endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy (required), and skin changes; anasarca | Multiple (pulmonary symptoms, hepatosplenomegaly); anasarca | Multiple (hepatosplenomegaly, renal dysfunction, bone marrow reticulin fibrosis); anasarca; adrenal hemorrhages; eruptive cherry hemangiomas | Multiple (pulmonary symptoms, renal dysfunction) | Multiple (pulmonary, renal); additional autoimmune phenomena (autoimmune hemolytic anemia, paraneoplastic pemphigus, immune thrombocytopenia, etc) |

| Exposure history risk | N/A | Increased HIV exposure history | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Key disease mimics | Multiple myeloma, plasmacytoma, lymphoma | HLH, primary effusion lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma | HLH, sepsis, SLE | IgG4-RD | ALPS, Rosai-Dorfman |

| Histopathological features | |||||

| Lymph node histopathology | Plasmacytic with increased monoclonal plasma cells | HHV8 positive plasmablastic proliferation | Hypervascular or mixed subtype with germinal center regression, vascularity, and FDC prominence | Plasmacytic or mixed subtype with germinal center hyperplasia, vascularity, and increased plasma cells; frequently meets criteria for IgG4-RD lymphadenopathy | 3 potential histopathological subtypes (hypervascular, mixed, plasmacytic) |

| Bone marrow biopsy | Clonal plasma cells, megakaryocyte hyperplasia and atypia | HHV8 latent nuclear antigen (LNA) positive plasmablasts | Megakaryocyte hyperplasia, reticulin fibrosis | Hypercellularity, megakaryocytic atypia, and plasmacytosis (nonspecific) | Hypercellularity, megakaryocytic atypia, and plasmacytosis (nonspecific) |

Anemia: mild (10-12 g/dL); moderate (8-10 g/dL); severe (<8 g/dL). Ranges provided for each disease are estimated but do not preclude patient subsets outside this range.

Fever, sweats, weight loss, malaise.

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALPS, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; LAD, lymphadenopathy; LNA, latent nuclear antigen; N/A, not applicable; PHGG, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

In the context of her exposure history and co-occurring fever, fatigue, hepatosplenomegaly, and anemia, the patient was suspected to have babesiosis; however, blood smear and serology testing was negative. A diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) was suspected, but antinuclear antibody test (ANA) also returned negative. Over the course of 4 months and several hospital admissions, our patient received broad rheumatologic and infectious workups, all of which were diagnostically inconclusive. Eventually, a core needle biopsy was performed on an enlarged right cervical LN out of concern for malignancy, revealing findings consistent with reactive changes and no evidence of involvement by a lymphoma or plasma cell neoplasm.

Diagnosing iMCD

For all patients with CD, a lymph node (LN) biopsy is required to make the diagnosis. While CD subtypes have a broad spectrum of histopathological changes and the clinical significance of distinguishing them is unclear, iMCD-TAFRO—the CD subtype with the poorest prognostic outcomes—tends to exhibit the most homogeneous and specific histopathological features. As such, obtaining appropriate LN tissue is critical. A few LN biopsy methods are commonly employed to evaluate cytology and architecture, including (1) fine-needle aspiration (FNA), (2) core LN biopsy, and (3) excisional LN biopsy. FNA of an abnormal LN, often in accessible areas such as the cervical region, is the least invasive of the 3 evaluation techniques and provides variable information regarding LN cytology; however, its diagnostic applicability is limited in diseases such as CD, which rely on a constellation of changes and overarching LN architecture. It also has limited utility for lymphoma.4,23 A core LN biopsy can be employed for a broader set of diagnostic indications than FNA but sheds light on only a small portion of the LN, often resulting in sampling error (as observed in this patient).4,24 Compared with core LN biopsy, excisional LN biopsy of an entire LN enables histopathologic evaluation of a large amount of tissue regarding both cellularity and architecture.4 Particularly if lymphoma, CD, or other lymphoproliferative disorders are suspected, excisional LN biopsy is the gold standard, with core LN biopsy secondarily recommended only if anatomic accessibility precludes this option.

Histopathologic features consistent with iMCD that are observed from an excisional LN biopsy, along with clinically multicentric lymphadenopathy, constitute the 2 major criteria to make an iMCD diagnosis according to international consensus diagnostic criteria. In addition to both major criteria, a minimum of 2 of 11 minor criteria with at least 1 laboratory abnormality are required.3 Furthermore, the absence of HHV8 infection must be confirmed—via LANA1 testing of LN or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of serum—as well as the exclusion of other infectious, autoimmune, and neoplastic disorders on the differential for iMCD. The iMCD major and minor criteria, as well as diseases necessary for exclusion, are summarized in Table 4. The clinical features and natural history of CD are being studied through the ACCELERATE natural history registry,25 a global patient registry led by the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN) that patients can enroll themselves in directly www.cdcn.org/accelerate.

Diagnostic criteria for iMCD3

| I. Major criteria (need both): |

| 1. Histopathologic lymph node features consistent with the iMCD spectrum (Figure 1) Features along the iMCD spectrum include (need grade 2 to 3 for either regressive GCs or plasmacytosis at minimum): |

| Regressed/atrophic/atretic germinal centers, often with expanded mantle zones composed of concentric rings of lymphocytes in an “onion-skinning” appearance |

| FDC prominence |

| Vascularity, often with prominent endothelium in the interfollicular space and vessels penetrating into the GCs with a “lollipop” appearance |

| Sheetlike, polytypic plasmacytosis in the interfollicular space |

| Hyperplastic GCs |

| 2. Enlarged lymph nodes (≥1 cm in short-axis diameter) in ≥2 lymph node stations |

| II. Minor criteria (need at least 2 of 11 criteria with at least 1 laboratory criterion) |

| Laboratory* |

| 1. Elevated CRP (>10 mg/L) or ESR (>15 mm/h)† |

| 2. Anemia (hemoglobin <12.5 g/dL for males, <11.5 g/dL for females) |

| 3. Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150 k/µL) or thrombocytosis (platelet count >400 k/µL) |

| 4. Hypoalbuminemia (albumin <3.5 g/dL) |

| 5. Renal dysfunction (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) or proteinuria (total protein 150 mg/24 h or 10 mg/100 ml) |

| 6. Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (total γ globulin or immunoglobulin G > 1700 mg/dL) |

| Clinical |

| 1. Constitutional symptoms: night sweats, fever (>38 °C), weight loss, or fatigue (≥2 CTCAE lymphoma score for B symptoms) |

| 2. Large spleen and/or liver |

| 3. Fluid accumulation: edema, anasarca, ascites, or pleural effusion |

| 4. Eruptive cherry hemangiomatosis or violaceous papules |

| 5. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis |

| Exclusion criteria (must rule out each of these diseases that can mimic iMCD) |

| Infection-related disorders: |

| 1. HHV8 (infection can be documented by blood PCR; diagnosis of HHV8-associated MCD requires positive LANA-1 staining by IHC, which excludes iMCD) |

| 2. Clinical EBV-lymphoproliferative disorders, such as infectious mononucleosis or chronic active EBV (detectable EBV viral load not necessarily exclusionary) |

| 3. Inflammation and adenopathy caused by other uncontrolled infections (eg, acute or uncontrolled CMV, toxoplasmosis, HIV, active tuberculosis) |

| Autoimmune/autoinflammatory diseases (requires full clinical criteria; detection of autoimmune antibodies alone is not exclusionary): |

| 1. Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| 2. Rheumatoid arthritis |

| 3. Adult-onset Still disease |

| 4. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis |

| 5. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome |

| Malignant/lymphoproliferative disorders (these disorders must be diagnosed before or at the same time as iMCD to be exclusionary): |

| 1. Lymphoma (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin) |

| 2. Multiple myeloma |

| 3. Primary lymph node plasmacytoma |

| 4. FDC sarcoma |

| 5. POEMS syndrome‡ |

| Select additional features supportive of, but not required for diagnosis: |

| Elevated IL-6, sIL-2R, VEGF, IgA, IgE, LDH, and/or B2M |

| Reticulin fibrosis of bone marrow (particularly in patients with TAFRO syndrome) |

| I. Major criteria (need both): |

| 1. Histopathologic lymph node features consistent with the iMCD spectrum (Figure 1) Features along the iMCD spectrum include (need grade 2 to 3 for either regressive GCs or plasmacytosis at minimum): |

| Regressed/atrophic/atretic germinal centers, often with expanded mantle zones composed of concentric rings of lymphocytes in an “onion-skinning” appearance |

| FDC prominence |

| Vascularity, often with prominent endothelium in the interfollicular space and vessels penetrating into the GCs with a “lollipop” appearance |

| Sheetlike, polytypic plasmacytosis in the interfollicular space |

| Hyperplastic GCs |

| 2. Enlarged lymph nodes (≥1 cm in short-axis diameter) in ≥2 lymph node stations |

| II. Minor criteria (need at least 2 of 11 criteria with at least 1 laboratory criterion) |

| Laboratory* |

| 1. Elevated CRP (>10 mg/L) or ESR (>15 mm/h)† |

| 2. Anemia (hemoglobin <12.5 g/dL for males, <11.5 g/dL for females) |

| 3. Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150 k/µL) or thrombocytosis (platelet count >400 k/µL) |

| 4. Hypoalbuminemia (albumin <3.5 g/dL) |

| 5. Renal dysfunction (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) or proteinuria (total protein 150 mg/24 h or 10 mg/100 ml) |

| 6. Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (total γ globulin or immunoglobulin G > 1700 mg/dL) |

| Clinical |

| 1. Constitutional symptoms: night sweats, fever (>38 °C), weight loss, or fatigue (≥2 CTCAE lymphoma score for B symptoms) |

| 2. Large spleen and/or liver |

| 3. Fluid accumulation: edema, anasarca, ascites, or pleural effusion |

| 4. Eruptive cherry hemangiomatosis or violaceous papules |

| 5. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis |

| Exclusion criteria (must rule out each of these diseases that can mimic iMCD) |

| Infection-related disorders: |

| 1. HHV8 (infection can be documented by blood PCR; diagnosis of HHV8-associated MCD requires positive LANA-1 staining by IHC, which excludes iMCD) |

| 2. Clinical EBV-lymphoproliferative disorders, such as infectious mononucleosis or chronic active EBV (detectable EBV viral load not necessarily exclusionary) |

| 3. Inflammation and adenopathy caused by other uncontrolled infections (eg, acute or uncontrolled CMV, toxoplasmosis, HIV, active tuberculosis) |

| Autoimmune/autoinflammatory diseases (requires full clinical criteria; detection of autoimmune antibodies alone is not exclusionary): |

| 1. Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| 2. Rheumatoid arthritis |

| 3. Adult-onset Still disease |

| 4. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis |

| 5. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome |

| Malignant/lymphoproliferative disorders (these disorders must be diagnosed before or at the same time as iMCD to be exclusionary): |

| 1. Lymphoma (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin) |

| 2. Multiple myeloma |

| 3. Primary lymph node plasmacytoma |

| 4. FDC sarcoma |

| 5. POEMS syndrome‡ |

| Select additional features supportive of, but not required for diagnosis: |

| Elevated IL-6, sIL-2R, VEGF, IgA, IgE, LDH, and/or B2M |

| Reticulin fibrosis of bone marrow (particularly in patients with TAFRO syndrome) |

We have provided laboratory cutoff thresholds as guidance, but we recognize that some laboratories have slightly different ranges. We suggest that you use the upper and lower ranges from your particular laboratory to determine if a patient meets a particular laboratory Minor Criterion.

Evaluation of CRP is mandatory and tracking CRP levels is highly recommended, but ESR will be accepted if CRP is not available.

Diagnosis of disorders that have been associated with iMCD: paraneoplastic pemphigus, bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, autoimmune cytopenias, polyneuropathy (without diagnosing POEMS‡), glomerular nephropathy, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.

B2M, beta-2 microglobulin; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GC, germinal center; h, hour; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgE, immunoglobulin E; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

While it is important to select an appropriate biopsy method to make a CD diagnosis, there are a number of barriers to diagnosis that are histopathologically related (eg, selection of sensitive biopsy technique, inter-pathologist discrepancy in recognizing histopathology, absence of objective histopathological biomarkers) and clinically related (eg, nonspecific clinical findings, absence of a noninvasive clinical test). Therefore, ultimately, to diagnose MCD, it is essential for clinicians and pathologists to work together to holistically review all these findings in order to discriminate MCD from closely overlapping entities. While clinical, laboratory, and histopathological patterns of each MCD subtype are delineated in Table 3, Table 5 provides an analogous comparison between iMCD-TAFRO and commonly overlapping nonclonal causes of generalized lymphadenopathy on its differential.26–30

Non-neoplastic causes of generalized lymphadenopathy on the differential for iMCD-TAFRO

| . | Non-neoplastic causes of generalized lymphadenopathy . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Autoimmune-related diseases on the differential . | Infectious diseases on the differential . | Inflammatory diseases on the differential . | ||||||

| . | SLE . | Sarcoidosis . | ALPS . | HIV infection . | Miliary TB . | Viral sepsis . | iMCD-TAFRO . | HLH . | MIS-C/A . |

| Laboratory assessments | |||||||||

| CRP | +/++ | +/++ | +/++ | +/++ | ++/+++ | ++/+++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Hemoglobin‡ | Mild to moderate anemia | Mild to moderate anemia | Mild to severe anemia | Mild to moderate anemia | Moderate to severe anemia (varies) | Moderate to severe anemia (varies) | Moderate to severe anemia | Typically severe anemia | Mild to moderate anemia |

| Platelets | Thrombocytopenia | Aberrations uncommon (rare thrombocytopenia) | Thrombocytopenia | Thrombocytopenia | Thrombocytopenia in some | Thrombocytopenia often (mild to severe) | Severe thrombocytopenia | Severe thrombocytopenia | More commonly mild to moderate thrombocytopenia |

| WBC | Leukopenia | Leukopenia (BM involvement) | Neutropenia | Lymphopenia predominantly, neutropenia | Leukocytosis or leukocytopenia | Leukocytosis or leukopenia (can be severe), lymphopenia | Not a primary abnormality (leukocytosis in some) | Neutropenia | Leukocytosis and neutrophilia, lymphopenia common |

| LFTs | Uncommon elevated LFTs (most commonly non-immune related) | Mild elevation of LFTs (if liver involvement) | Elevated liver enzymes and ALP | Can have elevated liver enzymes (not typical presenting sign) | Elevated liver enzymes, hypoalbuminemia (if liver involvement) | Elevated liver enzymes, hypoalbuminemia | Elevated ALP without hyperbilirubinemia and transaminase elevation | Elevated transaminases and bilirubin; hypoalbuminemia and prolonged PT/INR and PTT | Elevated transaminases common |

| Immunoglobulins | Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia | Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia | Hypergammaglobulinemia | Hypogammaglobulinemia (late-stage) | Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia | Commonly hypogammaglobulinemia (but hypergammaglobulinemia in chronic/recurrent cases) | Normal, or mild hypergammaglobulinemia | Varies | Hypergammaglobulinemia common |

| Other unique laboratory features | ANA+ (98%), dsDNA+, renal insufficiency (lupus nephritis), hypocomplementemia | Hypercalcemia, elevated serum ACE (nonspecific) | Revealing genetic testing (FAS, FASL, CASP10, etc), elevated IL-10 and FASL, elevated double-negative T cells | HIV-1/2 positive on antigen/ antibody combination immunoassay | Hyponatremia (SIADH), hypercalcemia (granulomas) | Positive microbiological findings (eg, blood culture, CSF PCR); elevated IL-6 | Renal insufficiency; elevated IL-6, VEGF (variable) | Elevated ferritin, soluble CD25, triglycerides, and sIL-2R; low fibrinogen | Elevated ferritin, procalcitonin, IL-6; evidence of recent SARS-CoV2 infection |

| Clinical presentation | |||||||||

| Constitutional signs | +/++ | +/++ | +/++ | +/++ | ++/+++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Organ involvement | Multiple (skin, renal, MSK/joints, cardiac) | Multiple (pulmonary, skin, eyes, cardiac) | Multiple (hepatosplenomegaly, autoimmune hematological and endocrine involvement) | Multiple (lymphoid tissue, CNS, GI, skin) | Multiple (pulmonary, hepatomegaly, spleen, bone marrow, CNS) | Multiple (renal dysfunction, cardiac dysfunction, respiratory failure, liver dysfunction) | Multiple (hepatosplenomegaly, renal, bone marrow) | Multiple (hepatosplenomegaly, bone marrow hemophagocytosis, inflammatory CNS findings) | Multiple (cardiac dysfunction, mucocutaneous, and GI involvement most common) |

| Exposure history risk | N/A | N/A | N/A | High-risk sexual activity, IV drug use | Health care/ correctional facilities, high TB burden areas, young age | Viral pathogen-specific exposures | N/A (HHV8-MCD associated with HHV8 risk factors) | N/A (infection-related exposure history for infection-related HLH) | Exposure to SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals |

| Additional unique features | Hallmark rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis, serositis | Ocular involvement (uveitis), erythema nodosum, hilar lymphadenopathy | Autoimmune endocrinopathies, autoimmune hematologic abnormalities (AIHA, ITP, etc), less commonly autoimmune | Oral candidiasis and recurrent opportunistic infections, retroviral seroconversion syndrome | Miliary pulmonary infiltrates, meningitis in some | Pathogen-specific viral exanthems, respiratory symptoms, and neurological symptoms | Anasarca and fluid accumulation (nonspecific), reticulin fibrosis in bone marrow, adrenal hemorrhage | Nearly all with hepatitis, 1/3 with generalized neurological findings, lymphadenopathy not as prominent | Temporal association with COVID infection; fever and GI symptoms most common |

| Lymph node pattern | |||||||||

| % Presenting with lymphadenopathy | 33%-69% | >90% (hilar) 20%-45% (hilar) | Part of diagnostic criteria | Common (up to 70%-90%) | Common (~50%-80%) | Occurs, but not usually primary feature (varies by pathogen) | Part of diagnostic criteria | ~30%-60% | Common (~50%-60%) |

| Primary presenting LN pattern | Generalized (majority) | Generalized (majority) | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized |

| Preferred LN stations | Cervical | Hilar | Fluctuates (cervical, axillary, inguinal; others also observed) | Cervical, axillary | Mediastinal, hilar, abdominal | Varies by pathogen (cervical common) | Varies | Varies (cervical, axillary, mediastinal, hilar, abdominal) | Cervical, axillary, inguinal |

| LN histology | Nonspecific findings (follicular hyperplasia, increased vascularity, scattered plasma cells); most specific finding: coagulative necrosis with hematoxylin bodies | Non-necrotizing noncaseating granulomas | Most commonly lymphoid hyperplasia, paracortical expansion | Morphological pattern depends on stage (eg, follicular hyperplasia, follicular involution, and diffuse pattern) | Necrotizing, caseating granulomas | Reactive changes (follicular and paracortical hyperplasia); EBV (atypical lymphocytes and B-cell proliferation) and CMV (owl-eye cells) have specific findings | Hypervascular or mixed subtype with germinal center regression, vascularity, and FDC prominence | Sinus histiocytosis and hemophagocytosis, histiocytic infiltration, paracortical expansion | Reactive hyperplasia |

| . | Non-neoplastic causes of generalized lymphadenopathy . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Autoimmune-related diseases on the differential . | Infectious diseases on the differential . | Inflammatory diseases on the differential . | ||||||

| . | SLE . | Sarcoidosis . | ALPS . | HIV infection . | Miliary TB . | Viral sepsis . | iMCD-TAFRO . | HLH . | MIS-C/A . |

| Laboratory assessments | |||||||||

| CRP | +/++ | +/++ | +/++ | +/++ | ++/+++ | ++/+++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Hemoglobin‡ | Mild to moderate anemia | Mild to moderate anemia | Mild to severe anemia | Mild to moderate anemia | Moderate to severe anemia (varies) | Moderate to severe anemia (varies) | Moderate to severe anemia | Typically severe anemia | Mild to moderate anemia |

| Platelets | Thrombocytopenia | Aberrations uncommon (rare thrombocytopenia) | Thrombocytopenia | Thrombocytopenia | Thrombocytopenia in some | Thrombocytopenia often (mild to severe) | Severe thrombocytopenia | Severe thrombocytopenia | More commonly mild to moderate thrombocytopenia |

| WBC | Leukopenia | Leukopenia (BM involvement) | Neutropenia | Lymphopenia predominantly, neutropenia | Leukocytosis or leukocytopenia | Leukocytosis or leukopenia (can be severe), lymphopenia | Not a primary abnormality (leukocytosis in some) | Neutropenia | Leukocytosis and neutrophilia, lymphopenia common |

| LFTs | Uncommon elevated LFTs (most commonly non-immune related) | Mild elevation of LFTs (if liver involvement) | Elevated liver enzymes and ALP | Can have elevated liver enzymes (not typical presenting sign) | Elevated liver enzymes, hypoalbuminemia (if liver involvement) | Elevated liver enzymes, hypoalbuminemia | Elevated ALP without hyperbilirubinemia and transaminase elevation | Elevated transaminases and bilirubin; hypoalbuminemia and prolonged PT/INR and PTT | Elevated transaminases common |

| Immunoglobulins | Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia | Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia | Hypergammaglobulinemia | Hypogammaglobulinemia (late-stage) | Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia | Commonly hypogammaglobulinemia (but hypergammaglobulinemia in chronic/recurrent cases) | Normal, or mild hypergammaglobulinemia | Varies | Hypergammaglobulinemia common |

| Other unique laboratory features | ANA+ (98%), dsDNA+, renal insufficiency (lupus nephritis), hypocomplementemia | Hypercalcemia, elevated serum ACE (nonspecific) | Revealing genetic testing (FAS, FASL, CASP10, etc), elevated IL-10 and FASL, elevated double-negative T cells | HIV-1/2 positive on antigen/ antibody combination immunoassay | Hyponatremia (SIADH), hypercalcemia (granulomas) | Positive microbiological findings (eg, blood culture, CSF PCR); elevated IL-6 | Renal insufficiency; elevated IL-6, VEGF (variable) | Elevated ferritin, soluble CD25, triglycerides, and sIL-2R; low fibrinogen | Elevated ferritin, procalcitonin, IL-6; evidence of recent SARS-CoV2 infection |

| Clinical presentation | |||||||||

| Constitutional signs | +/++ | +/++ | +/++ | +/++ | ++/+++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Organ involvement | Multiple (skin, renal, MSK/joints, cardiac) | Multiple (pulmonary, skin, eyes, cardiac) | Multiple (hepatosplenomegaly, autoimmune hematological and endocrine involvement) | Multiple (lymphoid tissue, CNS, GI, skin) | Multiple (pulmonary, hepatomegaly, spleen, bone marrow, CNS) | Multiple (renal dysfunction, cardiac dysfunction, respiratory failure, liver dysfunction) | Multiple (hepatosplenomegaly, renal, bone marrow) | Multiple (hepatosplenomegaly, bone marrow hemophagocytosis, inflammatory CNS findings) | Multiple (cardiac dysfunction, mucocutaneous, and GI involvement most common) |

| Exposure history risk | N/A | N/A | N/A | High-risk sexual activity, IV drug use | Health care/ correctional facilities, high TB burden areas, young age | Viral pathogen-specific exposures | N/A (HHV8-MCD associated with HHV8 risk factors) | N/A (infection-related exposure history for infection-related HLH) | Exposure to SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals |

| Additional unique features | Hallmark rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis, serositis | Ocular involvement (uveitis), erythema nodosum, hilar lymphadenopathy | Autoimmune endocrinopathies, autoimmune hematologic abnormalities (AIHA, ITP, etc), less commonly autoimmune | Oral candidiasis and recurrent opportunistic infections, retroviral seroconversion syndrome | Miliary pulmonary infiltrates, meningitis in some | Pathogen-specific viral exanthems, respiratory symptoms, and neurological symptoms | Anasarca and fluid accumulation (nonspecific), reticulin fibrosis in bone marrow, adrenal hemorrhage | Nearly all with hepatitis, 1/3 with generalized neurological findings, lymphadenopathy not as prominent | Temporal association with COVID infection; fever and GI symptoms most common |

| Lymph node pattern | |||||||||

| % Presenting with lymphadenopathy | 33%-69% | >90% (hilar) 20%-45% (hilar) | Part of diagnostic criteria | Common (up to 70%-90%) | Common (~50%-80%) | Occurs, but not usually primary feature (varies by pathogen) | Part of diagnostic criteria | ~30%-60% | Common (~50%-60%) |

| Primary presenting LN pattern | Generalized (majority) | Generalized (majority) | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized | Generalized |

| Preferred LN stations | Cervical | Hilar | Fluctuates (cervical, axillary, inguinal; others also observed) | Cervical, axillary | Mediastinal, hilar, abdominal | Varies by pathogen (cervical common) | Varies | Varies (cervical, axillary, mediastinal, hilar, abdominal) | Cervical, axillary, inguinal |

| LN histology | Nonspecific findings (follicular hyperplasia, increased vascularity, scattered plasma cells); most specific finding: coagulative necrosis with hematoxylin bodies | Non-necrotizing noncaseating granulomas | Most commonly lymphoid hyperplasia, paracortical expansion | Morphological pattern depends on stage (eg, follicular hyperplasia, follicular involution, and diffuse pattern) | Necrotizing, caseating granulomas | Reactive changes (follicular and paracortical hyperplasia); EBV (atypical lymphocytes and B-cell proliferation) and CMV (owl-eye cells) have specific findings | Hypervascular or mixed subtype with germinal center regression, vascularity, and FDC prominence | Sinus histiocytosis and hemophagocytosis, histiocytic infiltration, paracortical expansion | Reactive hyperplasia |

Anemia: mild (10-12 g/dL); moderate (8-10 g/dL); severe (<8 g/dL). Ranges provided for each disease are estimated but do not preclude patient subsets outside this range.

AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALPS, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; BM, bone marrow; CMV, cytomegalovirus; FASL, FAS ligand; GI, gastrointestinal; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; MIS-C/A, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adults; MSK, musculoskeletal; N/A, not applicable; PHGG, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia; PT/INR, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; SARS‑CoV‑2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion; TB, tuberculosis; WBC, white blood cell.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

After a core LN biopsy provided insufficient tissue to make a diagnosis, a complete excisional biopsy of an FDG-avid, enlarged right axillary LN revealed features consistent with CD. The patient was found to have LN pathology consistent with the hyaline vascular/hypervascular histopathological subtype of CD, and HHV8 testing by LANA1 of LN was negative. The patient also met the consensus criteria for TAFRO syndrome. The final diagnosis was iMCD-TAFRO. Following diagnosis, the patient received IL-6 blockade therapy with siltuximab. She had a complete clinical response and has been in remission for more than a year.

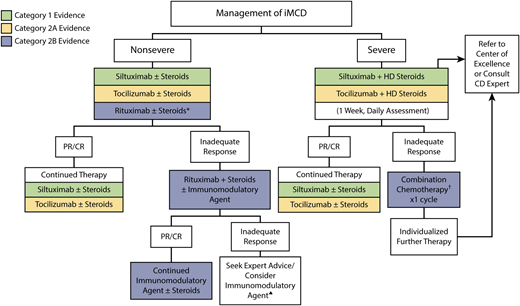

Evidence-based consensus iMCD treatment recommendations

As the hypercytokinemia involved in iMCD is often driven by IL-6, IL-6 blockade has been incorporated in international treatment guidelines.3 Siltuximab, a monoclonal antibody against soluble IL-6, is the only FDA-approved therapy for iMCD and is recommended first-line in cases where siltuximab is unavailable, tocilizumab—a monoclonal antibody against soluble and membrane-bound IL-6 receptor—may be recommended for off-label use.2 Retrospective and post hoc analyses have supported the efficacy of siltuximab as first-line treatment for severe and nonsevere iMCD, including evidence of superior progression-free survival compared with both placebo as well as rituximab-containing and chemotherapy-based treatment regimens.33–34 Most recently, Pierson et al (2023)32 conducted a retrospective cohort evaluation of the ACCELERATE natural history registry that provided evidence in support of first-line therapy recommendations included in international treatment guidelines. This study additionally provides evidence in support of cytotoxic chemotherapy in patients with severe refractory disease and limit corticosteroid monotherapy.

However, first-line IL-6-blocking therapy is an effective therapeutic option for approximately 30% to 50% of patients,32–35 and a large portion of iMCD patients do not respond to therapy. A treatment algorithm summarizing the most updated international guidelines for iMCD is included in Figure 2.

Evidence-based treatment guidelines for iMCD.31 IL-6 blockade, including siltuximab and secondarily tocilizumab, in combination with high-dose steroids is recommended as first-line therapy in international treatment guidelines for severe iMCD. Cytotoxic chemotherapy is recommended as second-line therapy in severe patients, while rituximab in combination with steroid therapy is recommended second-line in nonsevere patients. Retrospective validation supports these guidelines and is supportive against steroid monotherapy.32

Evidence-based treatment guidelines for iMCD.31 IL-6 blockade, including siltuximab and secondarily tocilizumab, in combination with high-dose steroids is recommended as first-line therapy in international treatment guidelines for severe iMCD. Cytotoxic chemotherapy is recommended as second-line therapy in severe patients, while rituximab in combination with steroid therapy is recommended second-line in nonsevere patients. Retrospective validation supports these guidelines and is supportive against steroid monotherapy.32

Emerging therapies

Recent investigations have implicated other therapeutic targets, such as mTOR and JAK1/2, as well as their respective immunomodulators, such as sirolimus and ruxolitinib, to have clinical benefit. Additionally, myeloma-directed therapies, such as thalidomide36 and bortezomib,37 have demonstrated promise, especially for subtypes such as iMCD-IPL. Further research is being conducted regarding novel intracellular pathways and mechanisms that can be targeted for potential emerging therapies.38,39

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of iMCD is paramount for initiating appropriate therapy, which can significantly improve morbidity and patient outcomes otherwise exacerbated by treatment delay. Current iMCD diagnostic criteria require both (1) a LN biopsy to confirm non-specific histopathology and (2) observation of similarly non-specific clinical/laboratory features. Thus, clinicians and pathologists must work together to recognize these cases from a host of overlapping conditions. In the case of our patient, appropriate therapeutic management was delayed by more than 4 months until an open excisional LN biopsy was performed. Ultimately, a multimodal assessment of clinical, laboratory-based, and histopathological features between clinicians and pathologists was critical for recognizing MCD. While a broad differential for generalized lymphadenopathy can often leave off MCD subtypes in favor of more common etiologies, it is always important to consider iMCD on the differential for generalized lymphadenopathy with constitutional symptoms. Even if iMCD is a rare cause of generalized lymphadenopathy and systemic inflammation, it is a complicated, life-threatening, and highly actionable cause.

This case also highlights that further research is required to explore methods for shortening time to diagnosis for iMCD, which can mimic neoplastic diagnoses such as lymphoma as well as a host of other inflammatory and infectious diseases.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Sally Nijim has no competing financial interests to declare.

David C. Fajgenbaum has received consulting fees and research funding from EUSA Pharma and study drug (with no funding) from Pfizer for a clinical trial of sirolimus.

Off-label drug use

Sally Nijim: Nothing to disclose.

David C. Fajgenbaum: The article discusses off-label drug use of sirolimus, ruxolitinib, thalidomide, bortezomib, rituximab, corticosteroids, tocilizumab, and cytotoxic chemotherapy for iMCD.