Abstract

High-dose melphalan supported by autologous transplantation has been the standard of care for eligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma for nearly 30 years. Several randomized clinical trials have reaffirmed the strong position of transplant in the era of triplets combining proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, and dexamethasone. Although quadruplets are becoming the standard in transplantation programs, no data are currently available on the need for a transplant with new regimens incorporating anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies. Outcomes remain heterogeneous, with different response depths and durations depending on the cytogenetics at diagnosis. The improvement of disease prognostication using sensitive and specific tools allows for adapting the strategy to initial and dynamic risks. This review examines which patients need a transplant, when transplantation is preferable, and why.

Learning Objectives

Explain how the evolution of transplant-based strategies over time affects patient outcomes

Identify patterns of the disease and/or patient characteristics that could make it possible to avoid frontline transplant

CLINICAL CASE

A 52-year-old man was diagnosed with immunoglobulin G lambda myeloma in March 2024 after a right iliac plasmacytoma was biopsied. The sternal bone marrow aspirate showed the presence of 14% clonal plasma cells. The monoclonal spike IgG lambda was dosed at 23 g/L and the free light chain lambda at 126 mg/L. The kappa/lambda free light chain ratio was 96. The international scoring system was favorable, and the lactate dehydrogenase level was normal. Fluorescent in situ hybridization of sorted plasma cells did not reveal any translocation (t[4;14] or t[14;16]) or deletion (del[17p]), conferring a high cytogenetic risk. Baseline positron emission tomography computed tomography showed many osteolytic lesions of the ribs, with a large lesion centered on the sixth left rib involving the soft tissues (paramedullary disease), a pathological fracture of the T9 vertebra, several lytic lesions of the T1 and T6 vertebrae, and a bulky hypermetabolic right iliac lesion. The patient started a quadruple induction combining daratumumab, bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) accounts for 1% to 1.8% of all cancers and 10% to 15% of all hematologic malignancies. MM was responsible for 22% of deaths related to hematological cancers in the United States in 2022.1 Although MM remains an incurable disease for most patients, overall survival (OS) has significantly improved over the past decades with the emergence of new classes of drugs, including immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), proteasome inhibitors (PIs), and anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies. The 5-year survival rate increased from 25% in 1975-1977 to approximately 60% in 2012-2018.2 For transplant-eligible (TE) patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM), the standard of care includes an induction regimen before a high-dose (HD) melphalan course with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT); consolidation therapy after ASCT remains an option before systematic lenalidomide-based maintenance.3

Evolution of transplant-based strategies

Transplant improves outcomes

After the first case reports and the proof-of-concept of dose response,4,5 the use of HD melphalan with ASCT as a standard in TE patients was initially established based on many phase 2 and phase 3 randomized trials vs conventional chemotherapy conducted during the 1990s.6-14 In this era prior to novel agents, transplant resulted in improved event-free survival (EFS), progression-free survival (PFS), and/or OS. The 2 negative trials compared transplant to standard-regimen VBMCP, which includes not only melphalan but cyclophosphamide (Table 1).15,16 From 2010 onward, high response rates achieved with the combination of IMiDs, PIs, and dexamethasone have led to a reassessment of the role of HD therapy in this new drug era. No fewer than 4 randomized clinical trials have confirmed that HD melphalan before transplant remains the cornerstone for TE NDMM.17-20 In the IFM 2009 trial, the median PFS was significantly longer in the transplant arm at 47 months compared to 35 months in the VRD-alone arm (P = .0001). An extended follow-up (FU) at 89.8 months did not reveal any differences in PFS2 (progression on next line of treatment-free survival) or OS.17,18 Interestingly, more than 60% of patients in both groups were still alive at 8 years of FU because of the efficacy of salvage treatments; 76.7% of patients treated up front with VRD alone who started a second line were able to receive ASCT at relapse. Similarly, in the DETERMINATION trial the median PFS was significantly longer in the ASCT group (67 months vs 46 months; P < .001). No difference in OS (5-year-OS rate, 79.2% vs 80.7%) was seen between VRD alone and VRD plus ASCT after a median FU of more than 6 years,19 despite only 28% of patients initially treated in the VRD arm receiving subsequent ASCT. Another large trial including more than 1500 patients compared VMP to ASCT (single or double): the EMN02/HO95 study reported, after a median FU of 75 months, a PFS benefit (56.7 vs 41.9 months; P < .0001), as well as PFS2, time to next treatment, and OS improvements (7-year OS, 69% vs 63%; P < .0342).20 The efficacy potential of carfilzomib also led to the hypothesis that transplant was no longer necessary: the phase 2 FORTE trial randomly assigned patients to 2 transplant strategies (with induction and consolidation based on carfilzomib, lenalidomide or cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone [KCD or KRD]) and a continuous treatment with KRD for 1 year. Although the response and minimal residual disease (MRD)-negativity rates were similar after consolidation in the KRD-alone and KRD plus ASCT arms, the sustained MRD-negativity rate and the median PFS were superior in the transplant arm (median PFS not reached vs 55.3 months; P = .0084).21 Notably, no study has randomly compared ASCT and a quadruple regimen containing an anti-CD38 antibody, which is the current standard. Only the IFM 2020-02 MIDAS study is currently asking this question in a subgroup of patients with a good prognosis, ie, patients who achieve an MRD-negativity rate inferior to 10−5 after 6 cycles of isatuximab, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in induction.22 Future directions aim to replace transplant with anti-BCMA immunotherapies and not just challenge it with quadruplets alone.23

Relevant randomized clinical trials comparing transplant with standard treatment in NDMM patients aged up to 70 years

| Study . | Starting year . | Number of randomized patients . | Induction . | Transplant regimen . | Standard regimen . | Survival benefit of transplant . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFM9010 | 1990 | 200 | VMCP/VBAP | Mel 140/TBI-8 | VMCP/VBAP | EFS + OS |

| MAG9011 | 1990 | 185 | VAMP | Cc/Cy/VP/Mel 140/TBI-12 | VMCP | EFS |

| MAG9114 | 1991 | 190 | VAMP | Bu/Mel 140 or Mel 200 | VMCP | EFS |

| MRC712 | 1993 | 401 | VAMPC | Mel 200 or Mel 140/TBI | ABCM | PFS + OS |

| S932116 | 1993 | 516 | VAD | Mel 140/TBI-12 | VBMCP | None |

| PETHEMA15 | 1994 | 164 | VBMCP/VBAD | Mel 200 or Mel 140/TBI-12 | VBMCP/VBAD | None |

| M97G13 | 1997 | 194 | VAD | Mel 100 × 2 | MP | EFS + OS |

| IFM200917,18 | 2010 | 700 | VRD ( × 3) | Mel 200 | VRD ( × 5) | PFS |

| DETERMINATION19 | 2010 | 722 | VRD ( × 3) | Mel 200 | VRD ( × 5) | PFS + EFS |

| EMN02/HO9520 | 2011 | 1197 | VCD ( × 3 or 4) | Mel 200 ( × 1 or × 2) | VMP | PFS + PFS2 + OS |

| FORTE21 | 2015 | 474 | KRD or KCD ( × 4) | Mel 200 | KRD ( × 8) | PFS |

| EMN CARTITUDE623 | 2024 | 750 planned | DVRD ( × 4) | Mel 200 | cilta-cel | ? |

| Study . | Starting year . | Number of randomized patients . | Induction . | Transplant regimen . | Standard regimen . | Survival benefit of transplant . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFM9010 | 1990 | 200 | VMCP/VBAP | Mel 140/TBI-8 | VMCP/VBAP | EFS + OS |

| MAG9011 | 1990 | 185 | VAMP | Cc/Cy/VP/Mel 140/TBI-12 | VMCP | EFS |

| MAG9114 | 1991 | 190 | VAMP | Bu/Mel 140 or Mel 200 | VMCP | EFS |

| MRC712 | 1993 | 401 | VAMPC | Mel 200 or Mel 140/TBI | ABCM | PFS + OS |

| S932116 | 1993 | 516 | VAD | Mel 140/TBI-12 | VBMCP | None |

| PETHEMA15 | 1994 | 164 | VBMCP/VBAD | Mel 200 or Mel 140/TBI-12 | VBMCP/VBAD | None |

| M97G13 | 1997 | 194 | VAD | Mel 100 × 2 | MP | EFS + OS |

| IFM200917,18 | 2010 | 700 | VRD ( × 3) | Mel 200 | VRD ( × 5) | PFS |

| DETERMINATION19 | 2010 | 722 | VRD ( × 3) | Mel 200 | VRD ( × 5) | PFS + EFS |

| EMN02/HO9520 | 2011 | 1197 | VCD ( × 3 or 4) | Mel 200 ( × 1 or × 2) | VMP | PFS + PFS2 + OS |

| FORTE21 | 2015 | 474 | KRD or KCD ( × 4) | Mel 200 | KRD ( × 8) | PFS |

| EMN CARTITUDE623 | 2024 | 750 planned | DVRD ( × 4) | Mel 200 | cilta-cel | ? |

ABCM, doxorubicin-carmustine-cyclophosphamide-melphalan; CC, lomustine; cilta-cel, ciltacabtagene-autoleucel; Cy, cyclophosphamide; DVRD, daratumumab-bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone; VAD, vincristine-doxorubicin-dexamethasone; VAMP, vincristine-doxorubicin- methylprednisolone; VAMPC, vincristine-doxorubicin-methylprednisolone-cyclophosphamide; VBAD, vincristine-carmustine-doxorubicin- dexamethasone; VBAP, vincristine-carmustine-doxorubicin-prednisone; VCD, bortezomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone; VMCP, vincristine- melphalan-cyclophosphamide-prednisone; VMP, bortezomib-melphalan-dexamethasone; VP, etoposide; VRD, bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone.

Nothing is better than melphalan 200 mg/m2 as a conditioning regimen

Given the initial data on the use of melphalan at 200 mg/m2 (Mel 200) without total body irradiation (TBI),8 the IFM95-02 trial randomly compared Mel 200 and Mel 140 plus 8 grays TBI (TBI-8) in TE NDMM. The results have established Mel 200 as the standard based on noninferior EFS and OS, along with lower toxicity (faster hematological recovery, shorter hospital stays, and less severe mucositis).24 More intensive regimens could theoretically allow for deeper responses and better survival.25 For this purpose, various combinations have been studied (Table 2). The use of a higher dose of melphalan is limited by excessive toxicity, and protective treatments like amifostine have not proven conclusive.26 Combining melphalan with other drugs is constrained by adverse effects, which could lead to unacceptable treatment-related-mortality.27 Among the combinations studied, melphalan with busulfan seems promising but requires pharmacokinetic monitoring to adjust the dose due to the risk of veno-occlusive disease.28 To avoid increased toxicity or to target the bone marrow microenvironment, conditioning regimens containing noncytotoxic treatments are an attractive approach. However, the IFM 2014-02 trial did not achieve its primary end point.29 Other studies incorporating new therapies, such as carfilzomib or selinexor, are underway, but so far no combination appears to be superior to Mel 200. Another approach could be to intensify conditioning only for patients with high-risk cytogenetics.30

Main randomized clinical trials assessing intensified regimens before transplant

| Trial . | Regimens . | Efficacy . | Safety . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFM phase 2 study25 | Mel 220 + anti-IL-6 vs Mel 220 | CR: 37.5% vs 11% | One toxic death Grade 4 mucositis: 62.5% |

| NCT0021743826 | Mel 280 + amifostine vs Mel 200 + amifostine | ORR: 74% vs 57% (P = .04) mPFS: 3.5 y vs 2.7 y mOS: 6.2 y vs 5.3 y | Grade 2/3 mucositis: 33% vs 12% (P = .004) |

| German study27 | Mel 100 × 2 + Ida 20 × 3 + Cy 60 × 2 vs Mel 100 × 2 | ORR: 85% vs 83% (P = .01) mEFS: 20 m vs 16 m (P = .08) mOS: 46 m vs 66 m (P = .02) | TRM: 20% vs 0% Grade 3/4 mucositis: 80% vs 27% (P < .01) |

| NCT0141317828 | Mel 70 × 2 + Bu × 4 vs Mel 200 | mPFS: 64.7 m vs 43.5 m (P = .022) 3-y 8 OS: 91% vs 89% | Mucositis: 96% vs 49% (P < .0001) Febrile neutropenia: 71% vs 30% (P < .001) |

| IFM2014-0229 | Mel 200 + ortezomib × 4 vs Mel 200 | CR: 23.4% vs 20.5% | Peripheral neuropathy: 4% vs 1.2% |

| Trial . | Regimens . | Efficacy . | Safety . |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFM phase 2 study25 | Mel 220 + anti-IL-6 vs Mel 220 | CR: 37.5% vs 11% | One toxic death Grade 4 mucositis: 62.5% |

| NCT0021743826 | Mel 280 + amifostine vs Mel 200 + amifostine | ORR: 74% vs 57% (P = .04) mPFS: 3.5 y vs 2.7 y mOS: 6.2 y vs 5.3 y | Grade 2/3 mucositis: 33% vs 12% (P = .004) |

| German study27 | Mel 100 × 2 + Ida 20 × 3 + Cy 60 × 2 vs Mel 100 × 2 | ORR: 85% vs 83% (P = .01) mEFS: 20 m vs 16 m (P = .08) mOS: 46 m vs 66 m (P = .02) | TRM: 20% vs 0% Grade 3/4 mucositis: 80% vs 27% (P < .01) |

| NCT0141317828 | Mel 70 × 2 + Bu × 4 vs Mel 200 | mPFS: 64.7 m vs 43.5 m (P = .022) 3-y 8 OS: 91% vs 89% | Mucositis: 96% vs 49% (P < .0001) Febrile neutropenia: 71% vs 30% (P < .001) |

| IFM2014-0229 | Mel 200 + ortezomib × 4 vs Mel 200 | CR: 23.4% vs 20.5% | Peripheral neuropathy: 4% vs 1.2% |

Bu, busulfan; Cy 60, cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg; Ida 20, idarubicine 20 mg/m2; mEFS, median EFS; mOS, median OS; mPFS, median PFS; Mel 280, melphalan 280 mg/m2; ORR, overall response rate; TRM, treatment-related mortality.

Single or tandem transplant?

To deepen responses and improve survival, many groups have evaluated tandem transplant (Table 3). The first demonstration of superiority of tandem over single transplant in the IFM 94 study was based on longer PFS and OS, particularly in patients who had not achieved at least a very good partial response after the first ASCT.31 The Italian Bologna 96 trial concluded that tandem transplant improved PFS but showed no advantage in OS.32 The results of these trials are difficult to apply today, as the regimens used are no longer standard. Tandem transplants conditioned with Mel 200 were evaluated in the GMMG HD2 trial, which failed to demonstrate superiority, possibly due to a high dropout rate.33 More recently, 2 randomized phase 3 trials have reported conflicting results. In the EMN02/HO95 study, tandem transplants significantly improved 5-year PFS (53.5% vs 44.9%; P = .036) and 5-year OS (80.3% vs 72.6%; P = .022).20 In contrast, the STAMINA trial showed no advantage for tandem transplants in either PFS or OS, even in patients with high-risk MM. Some biases, such as the high dropout rate before the second transplant and a prolonged duration of induction, should qualify the conclusions.34 Importantly, neither study was specifically designed or powered to address single vs tandem transplants in high-risk patients. As a result, double intensification still appears to be of interest, at least for the time being, and remains commonly used for patients with high-risk MM based on results from nonrandomized studies. Both the GMMG-CONCEPT and IFM2018-04 phase 2 trials demonstrated promising outcomes in these difficult-to-treat patients, utilizing quadruplet regimens for induction followed by tandem transplant, with a 3-year PFS rate of 68.9% and a 30-months PFS rate of 80%, respectively.35,36

Main randomized clinical trials comparing single and tandem transplant

| Trial . | Number of patients . | Regimens . | Efficacy . | Benefit . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFM 9431 | 399 | Mel 140/TBI vs Mel 140/TBI, then Mel 140 | mEFS: 25 vs 30 mo (P = .03) mPFS: 29 vs 36 mo (P < .01) mOS: 48 vs 58 mo (P = .01) | EFS + PFS + OS |

| Bologna 9632 | 321 | Mel 200 vs Mel 200, then Mel 120 + Bu 4 | mEFS: 23 vs 35 mo (P = .001) mPFS: 24 vs 42 mo (P < .001) mOS: 65 vs 71 mo (P = .09) | EFS + PFS + OS |

| GMMG HD233 | 358 | Mel 200 vs Mel 200, then Mel 200 | mEFS: 25 vs 28.7 mo mOS: 73 vs 75.3 mo | Not significant |

| EMN02/HO9520 | 1197 | Mel 200 vs Mel 200, then Mel 200 | 5y-PFS: 44.9% vs 53.5% (P = .036) 5y-OS: 72.6% vs 80.3% (P = .022) | PFS + OS |

| STAMINA34 | 758 | Mel 200 vs Mel 200, then VRD vs Mel 200, then Mel 200 | 38 mo-PFS: 58.5% vs 57.8% vs 53.9% 38 mo-OS: 81.8% vs 85.4% vs 83.7% | Not significant |

| Trial . | Number of patients . | Regimens . | Efficacy . | Benefit . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFM 9431 | 399 | Mel 140/TBI vs Mel 140/TBI, then Mel 140 | mEFS: 25 vs 30 mo (P = .03) mPFS: 29 vs 36 mo (P < .01) mOS: 48 vs 58 mo (P = .01) | EFS + PFS + OS |

| Bologna 9632 | 321 | Mel 200 vs Mel 200, then Mel 120 + Bu 4 | mEFS: 23 vs 35 mo (P = .001) mPFS: 24 vs 42 mo (P < .001) mOS: 65 vs 71 mo (P = .09) | EFS + PFS + OS |

| GMMG HD233 | 358 | Mel 200 vs Mel 200, then Mel 200 | mEFS: 25 vs 28.7 mo mOS: 73 vs 75.3 mo | Not significant |

| EMN02/HO9520 | 1197 | Mel 200 vs Mel 200, then Mel 200 | 5y-PFS: 44.9% vs 53.5% (P = .036) 5y-OS: 72.6% vs 80.3% (P = .022) | PFS + OS |

| STAMINA34 | 758 | Mel 200 vs Mel 200, then VRD vs Mel 200, then Mel 200 | 38 mo-PFS: 58.5% vs 57.8% vs 53.9% 38 mo-OS: 81.8% vs 85.4% vs 83.7% | Not significant |

Bu 4, busulfan 4 mg/kg; Mel 140, melphalan 140 mg/m2.

Who needs a transplant today?

After triplets, quadruplet regimens combining an anti-CD38 antibody, bortezomib, an IMiD, and dexamethasone have revolutionized frontline treatment and significantly improved prognosis (Table 4). The phase 3 CASSIOPEA trial led to the approval of the daratumumab-bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone (DaraVTD) combination for induction and consolidation, demonstrating benefits in terms of stringent complete response (CR) and PFS. With longer FU, the study shows that the addition of daratumumab also prolonged OS (6-year-OS at 86.7% vs 77.7%; hazard ratio, 0.55; P < .0001.37 The GRIFFIN and PERSEUS trials demonstrated the superiority of DaraVRD over VRD in the same setting.38,39 The 4-year PFS rate was 84% vs 68% in PERSEUS (hazard ratio, 0.42; P < .0001). Isatuximab has also been evaluated in combination with VRD (IsaVRD): the preliminary results of IsaVRD in the GMMG HD7 study are promising.40 The integration of second-generation PIs in quadruplets is also being examined. Ixazomib, assessed in patients with standard cytogenetic risk, appears to be of limited benefit.41 On the other hand, carfilzomib used in quadruplet (or even quintuplet) regimens is associated with high levels of undetectable MRD, particularly in myeloma with high-risk cytogenetics.35,36,42,43 HD melphalan and transplant have been shown to improve response rates and MRD negativity rates before maintenance therapy in comparison with the postinduction time points,38,42 supporting the use of transplants even when employing these highly effective combinations. Robust comparative data on the potential de-escalation of therapy for patients who achieved MRD negativity after DaraKRD or IsaKRD induction are still awaited.23,44

MRD-negativity rates after induction and after consolidation with quadruplets in TE NDMM patients

| . | Type of quadruplet . | Number of patients/ specific population . | Induction details . | Postinduction MRD-negativity rate . | Number of ASCTs . | Consolidation details . | Postconsolidation/premaintenance MRD-negativity rate . | Outcomes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASSIOPEIA37 | DaraVTD | 543 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 35% (10–5) | 1 | 2 (4-week) cycles | 64% (10–5) | mPFS 83.7 m |

| GRIFFIN38 | DaraVRD | 104 | 4 (3-week) cycles | 22% (10–5) 1% (10–6) | 1 | 2 (3-week) cycles | 50% (10–5) 11% (10–6) | 4-y PFS 70% |

| PERSEUS39 | DaraVRD | 355 | 4 (4-week) cycles | NA | 1 | 2 (4-week) cycles | 57% (10–5) 34% (10–6) | 4-y PFS 84% |

| GMMG-HD740 | IsaVRD | 331 | 3 (6-week) cycles | 50% (10–5) | 1 | No consolidation | 72% (10–5) | NA |

| IFM2018-0141 | DaraIxaRD | 45 (SR) | 6 (3-week) cycles | 28% (10–5) 6% (10–6) | 1 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 51% (10–5) 40% (10–6) | 2-y PFS 93% |

| IFM2018-0436 | DaraKRD | 50 (HR) | 6 (4-week) cycles | 53% (10–5)a 43% (10–6)a | 2 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 97% (10–5)a 94% (10–6)a | 2.5-y PFS 80% |

| GMMG-CONCEPT35 | IsaKRD | 99 (HR) | 6 (4-week) cycles | NA | 2 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 68% (10–5) | 3-y PFS 69% |

| EMN24 IsKia42 | IsaKRD | 151 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 45% (10–5) 27% (10–6) | 1 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 77% (10–5) 67% (10–6) | NA |

| MASTER44 | DaraKRD | 123 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 37% (10–5) 23% (10–6) | 1 | MRD adapted | NA | NA |

| IFM2020-0222 | IsaKRD | 791 | 6 (4-week) cycles | 63% (10–5) 47% (10–6) | 0, 1, or 2 | MRD adapted | NA | NA |

| . | Type of quadruplet . | Number of patients/ specific population . | Induction details . | Postinduction MRD-negativity rate . | Number of ASCTs . | Consolidation details . | Postconsolidation/premaintenance MRD-negativity rate . | Outcomes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASSIOPEIA37 | DaraVTD | 543 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 35% (10–5) | 1 | 2 (4-week) cycles | 64% (10–5) | mPFS 83.7 m |

| GRIFFIN38 | DaraVRD | 104 | 4 (3-week) cycles | 22% (10–5) 1% (10–6) | 1 | 2 (3-week) cycles | 50% (10–5) 11% (10–6) | 4-y PFS 70% |

| PERSEUS39 | DaraVRD | 355 | 4 (4-week) cycles | NA | 1 | 2 (4-week) cycles | 57% (10–5) 34% (10–6) | 4-y PFS 84% |

| GMMG-HD740 | IsaVRD | 331 | 3 (6-week) cycles | 50% (10–5) | 1 | No consolidation | 72% (10–5) | NA |

| IFM2018-0141 | DaraIxaRD | 45 (SR) | 6 (3-week) cycles | 28% (10–5) 6% (10–6) | 1 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 51% (10–5) 40% (10–6) | 2-y PFS 93% |

| IFM2018-0436 | DaraKRD | 50 (HR) | 6 (4-week) cycles | 53% (10–5)a 43% (10–6)a | 2 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 97% (10–5)a 94% (10–6)a | 2.5-y PFS 80% |

| GMMG-CONCEPT35 | IsaKRD | 99 (HR) | 6 (4-week) cycles | NA | 2 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 68% (10–5) | 3-y PFS 69% |

| EMN24 IsKia42 | IsaKRD | 151 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 45% (10–5) 27% (10–6) | 1 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 77% (10–5) 67% (10–6) | NA |

| MASTER44 | DaraKRD | 123 | 4 (4-week) cycles | 37% (10–5) 23% (10–6) | 1 | MRD adapted | NA | NA |

| IFM2020-0222 | IsaKRD | 791 | 6 (4-week) cycles | 63% (10–5) 47% (10–6) | 0, 1, or 2 | MRD adapted | NA | NA |

Exceptions to MRD reported in intention-to-treat population (per protocol).

HR, (cytogenetics) high-risk; NA, not available; SR, (cytogenetics) standard risk.

Most recent treatment guidelines still recommend considering ASCT for all eligible NDMM patients,3,45-47 even with no difference in OS and promising data with quadruplet regimens. With increasingly effective treatments and concerns about the mutagenic effect of melphalan, some advocate delaying ASCT until the first relapse “in standard-risk patients responding well to therapy, provided stem cells are harvested early in the disease course.”47 Conclusions based on results from an overall population in a clinical trial may differ from individual benefits, especially since myeloma's biology is very heterogeneous, making personalization challenging. As the definition of prognostic risk is multiparametric and outcomes are difficult to predict with certainty at diagnosis, should the decision to transplant be as dynamic as the risk?

Eligibility and prognostic factors for transplant

At the time of diagnosis, the criteria for determining whether MM patients are eligible for a transplant include adequate organ function and overall fitness. Patients younger than age 65 years are typically considered good candidates. There is no randomized comparison of transplant vs no transplant for patients over the age of 65 years, but between 65 and 70 years, clinicians can decide on transplant eligibility based on a patient's fitness rather than a strict age cut-off.

Prognosis at diagnosis is based on the following:

Clinical and biological presentation features: these include extramedullary disease,48 the presence of more than 5% of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood,49 and high tumor burden.

Cytogenetics abnormalities: these abnormalities in sorted plasma cells reflect the intrinsic aggressiveness of the disease. While there are many definitions of high risk, an international effort has recently led to a consensus that is currently being published (Avet-Loiseau H, Davies FE, Samur M, et al).

Beyond age and eligibility criteria, transplant cannot be avoided for patients with high-risk characteristics at diagnosis. Patients with no high-risk characteristics are likely to have a good outcome. However, the most precise definition of cytogenetic risk involves the assessment of several abnormalities, including TP53 mutations, and the next-generation sequencing technique is not always routinely available. Given the risk of clonal evolution or poor response to treatment, it is preferable not to take a risk of losing the chance for better outcomes. Therefore, I propose up-front transplant as the first option.

Should the decision be reassessed during treatment?

Since the depth of response predicts long-term outcomes, it is advisable to explain to patients at the time of diagnosis that the initial treatment plan based on initial risk assessment may evolve over time, particularly based on post-induction results.

However, we still lack data on the relevance of adjusting treatment intensity based on induction results. One observation from the MASTER trial is that treatment for patients with high-risk myeloma should not be discontinued, even if both post-induction and post-transplant MRD assessments are negative.44 The MIDAS trial will likely provide insights into this question, as it randomizes patients who achieve MRD negativity after induction to either continue the same treatment or undergo a transplant.22 The concept of dynamic risk linked to the depth of response could also prompt discussions about a second “conditional” transplant, especially for patients who do not achieved MRD negativity after induction of after the first transplant.

When should a transplant be performed?

The lack of evidence supporting an OS benefit for transplant and the potential for long-term toxicities may argue for postponing ASCT until the first relapse. The earliest comparison of early vs delayed transplant dates back to 1998, which found no difference in OS.11 However, patients who underwent early transplant did experience a significantly longer period free from chemotherapy, suggesting a clinical benefit. It should be noted that directly comparing up-front vs deferred transplant is challenging due to potential confounders, such as inherent immortal time bias.

One risk of delaying ASCT is that patients may become ineligible for transplant upon relapse due to factors such as age, worsening general health, the emergence of comorbidities, or a more aggressive relapse. A retrospective analysis indicated that 35% of patients scheduled for delayed transplant did not receive it upon relapse, primarily due to their ineligibility for intensive treatment.50

On the other hand, concerns about an increased incidence of secondary primary malignancies with HD melphalan used in transplant have not been conclusively demonstrated in transplant vs nontransplant comparisons. The incidence of secondary primary malignancies in the IFM 2009 and DETERMINATION trials was similar between the 2 arms in an extended FU of 8 years.18,19

Therefore, up-front transplant remains the standard practice, while delaying it should be considered as an exception and discussed on a case-by-case basis.

Why should myeloma patients be transplanted?

Associating a transplant to a quadruplet combining an anti-CD38, a PI, an IMiD, and dexamethasone is a means of using an alkylating agent as well to combine therapeutic mechanisms of action and limit resistance of tumor plasma cells. It is above all the best way to achieve (sustained) MRD negativity,18 which is the most predictive tool for long-term outcomes.

Although data on the long-term FU of most efficient strategies are pending,22,35,36,42 quadruplets plus transplant are the most likely to achieve long-term disease control and hence a potential functional cure.

Future directions may include chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies, either as alternatives or additions to transplant.23

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient obtained a very good partial response after 1 cycle of DaraVRD and a stringent CR after 6 cycles of induction that was prolonged before transplant due to the patient's professional constraints. The patient received HD melphalan plus ASCT and was started on lenalidomide maintenance. As part of a biological study, MRD was assessed at the end of induction, which was found negative at 10−5. The cytogenetic analysis was also completed by NGS, finally revealing a high risk according to the international consensus definition. With hindsight, this confirms that frontline transplant should not have been avoided.

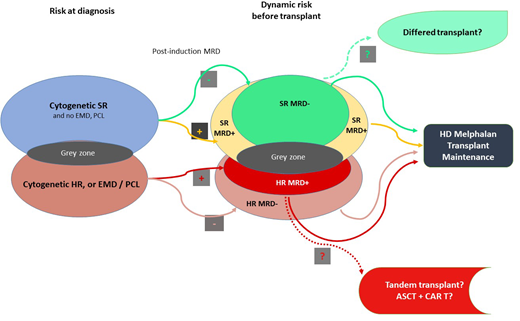

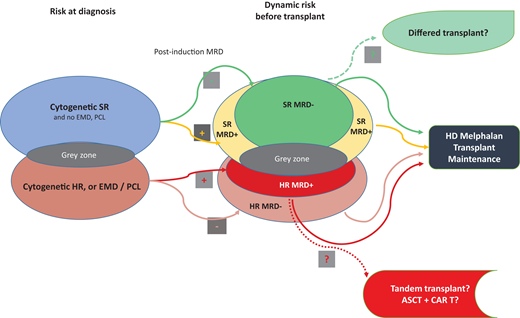

Multiparametric and dynamic criteria for considering the best treatment choice for TE patients with NDMM are shown in Figure 1.

Multiparametric and dynamic criteria to consider the best choice of treatment for TE patients with NDMM. ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantaon; CAR T, chimeric antigen receptor; EMD, extramedullary disease; HD, high dose; HR, high risk; MRD, minimal residual disease; PCL, plasma cell leukemia; SR, standard risk.

Multiparametric and dynamic criteria to consider the best choice of treatment for TE patients with NDMM. ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantaon; CAR T, chimeric antigen receptor; EMD, extramedullary disease; HD, high dose; HR, high risk; MRD, minimal residual disease; PCL, plasma cell leukemia; SR, standard risk.

Conclusion

All eligible NDMM patients should undergo ASCT until new data are available. Delaying ASCT should be considered on a case-by-case basis, ensuring that decisions are guided by individual patient characteristics and treatment responses. Future studies should focus on comparing new immunotherapies directly to transplant, but strategies using a transplant followed by new immunotherapies like chimeric antigen receptor T cells may be even better for curing as many patients as possible. Additionally, there is a critical need to define for each cytogenetics subgroup the predictive factors that can guide adapted treatment strategies. Specifically, the importance of achieving MRD negativity early after induction and its persistence vs transient MRD negativity needs clarification across different cytogenetic subgroups. Further research is required to enhance our understanding and develop tools capable of detecting MRD at sensitivities as high as 10−7 to 10−8, thereby optimizing treatment decisions and outcomes for patients with myeloma.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Aurore Perrot: honoraria: AbbVie, Amgen, Adaptive, Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Janssen, Menarini-Stemline, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda; advisory board: AbbVie, Amgen, Adaptive, Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Janssen, Menarini-Stemline, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda.

Off-label drug use

Aurore Perrot: nothing to disclose.