Abstract

Significant progress has been made in the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), with the introduction of several new drugs with different mechanisms of action. The treatment of newly diagnosed MM has evolved dramatically with the development of highly effective combinations that include 1 or more of the new drugs. Despite the continuing improvement in the overall survival of patients with MM, nearly a quarter of the patients have significantly inferior survival, often driven by a combination of factors, including tumor genetics and host frailty. The focus of initial therapy remains rapid control of the disease with reversal of the symptoms and complications related to the disease with minimal toxicity and a reduction in early mortality. The selection of the specific regimen, to some extent, depends on the ability of the patient to tolerate the treatment and the underlying disease risk. It is typically guided by results of randomized clinical trials demonstrating improvements in progression-free and/or overall survival. While increasing risk calls for escalating the intensity of therapy by using quadruplet combinations that can provide the deepest possible response and the use of autologous stem cell transplant, increasing frailty calls for a reduction in the intensity and selective use of triplet or doublet regimens. The choice of subsequent consolidation treatments and maintenance approaches, including duration of treatment, also depends on these factors, particularly the underlying disease risk. The treatment approaches for newly diagnosed myeloma continue to evolve, with ongoing trials exploring bispecific antibodies as part of initial therapy and CAR T cells for consolidation.

Learning Objectives

Review disease characteristics that determine outcomes and contribute to the treatment decision-making process in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.

Describe the efficacy and toxicity observed with various doublet, triplet, and quadruplet induction regimens.

Evaluate scenarios based on the initial response to treatment.

CLINICAL CASE

A 64-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with a 2-week history of back pain that started while he was playing golf. He has been relatively healthy, works full-time as an executive, and regularly exercises by walking at least 30 minutes daily. He has tried local measures, including local heat, lidocaine cream, and oral naproxen, with no relief. The plain film shows a compression fracture of the T8 vertebral body that was not evident on prior chest X-rays available in his medical records. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated compression of the T8 vertebral body with diffuse marrow enhancement involving multiple vertebral bodies, concerning for a pathological process such as myeloma. Additional workup showed a hemoglobin of 11.2 gm/dL (13.4 g/dL a year earlier), normal white blood count and platelets, and normal metabolic parameters, including normal calcium and serum creatinine. Serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation showed a monoclonal protein peak of 1.4 gm/dL of immunoglobulin G kappa, serum free light chain assay showed kappa at 121 mg/dL and lambda at 0.3 mg/dL with a ratio of 401, and 24-hour urine protein electrophoresis demonstrated 340 mg of M spike—kappa light chain and immunoglobulin G kappa fragments. A whole-body, low-dose computed tomographic scan showed multiple small lytic lesions scattered throughout the skeleton, with no additional fractures. A bone marrow biopsy was performed, which showed diffuse marrow infiltration with kappa light chain restricted plasma cells constituting 40% of the cellularity. Fluorescence in situ hybridization studies on the plasma cells showed monosomy 13, 1q gain, and t(4;14).

Diagnosis and risk-stratification

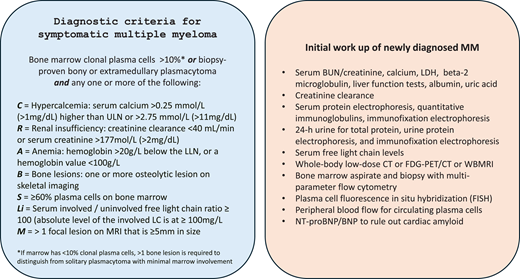

Multiple myeloma is always preceded by a premalignant phase—monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS)—characterized by the presence of a monoclonal protein as well as the presence of clonal plasma cells in the marrow, typically, but with no identifiable impact on the host and usually meriting no initiation of specific treatment.1,2 Additionally, many patients may have a discernable phase in between MGUS and active myeloma, termed smoldering multiple myeloma, in which concepts around early intervention continue to evolve, but considerable debate exists in terms of the timing and nature of treatment.3 Given this, an accurate diagnosis of active myeloma and distinction from MGUS and smoldering multiple myeloma remain a critical first step. The diagnostic criteria were most recently revised to include biomarkers that predicted the imminent development of end-organ damage as triggers for the initiation of treatment, a paradigm shift from the prior approach to this disease.2 The current diagnostic criteria and the essential elements of the initial workup are shown in Figure 1.

Diagnostic criteria for symptomatic myeloma and suggested initial workup. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; FDG-PET/CT, 18F-fludeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography/computed tomography; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; LC, light chain; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LLN, lower limit of normal; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ULN, upper limit of normal; WBMRI, whole-body magnetic resonance imaging.

Diagnostic criteria for symptomatic myeloma and suggested initial workup. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; FDG-PET/CT, 18F-fludeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography/computed tomography; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; LC, light chain; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LLN, lower limit of normal; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ULN, upper limit of normal; WBMRI, whole-body magnetic resonance imaging.

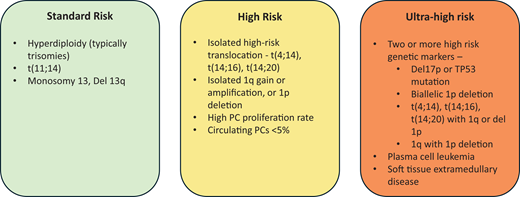

In addition to establishing the diagnosis, the initial workup should also focus on characterizing the disease to understand the patient's prognosis better and individualize the initial treatment.4 MM is a heterogeneous disease with varying outcomes that are driven by a variety of factors including tumor characteristics, host factors, and interaction between the tumor clone and the host (Figure 2).5 This is clear from the current outcomes, in which the median survival of the disease has improved from 3 years to over 10 years, but with nearly a quarter of patients still living less than 3 to 4 years from diagnosis.6,7 Among the many baseline features, genetic abnormalities in the tumor cell, age, and functional status play an outsized role in determining outcomes and, in turn, have become the major determinants of therapy selection for patients with newly diagnosed MM.

General approach to risk assessment in patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic MM. PC, plasma cell.

General approach to risk assessment in patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic MM. PC, plasma cell.

The genetic abnormalities in MM are well described and can be broadly categorized into structural and numerical abnormalities that can be identified through fluorescence in situ hybridization–based testing, which is currently the most commonly used and is readily available in the clinic, and mutations in individual genes that can be identified by genetic sequencing of the purified tumor cells, which is not commonly done in the current practice setting.3,5 The primary chromosomal abnormalities, those that have been identified in the earliest stages of MGUS, in turn, can be grouped into trisomies that typically include several odd-numbered chromosomes and translocations involving the Ig heavy chain locus on chromosome 14 with a common set of partner chromosomes (4, 6, 11, 16, and 20). Trisomies can be identified in approximately 40% of patients and translocations in approximately 45%, and in about 15% of patients, tumor cells with both abnormalities can be found.8 Other abnormalities, often termed secondary because they are identified later during the tumor cell evolution and are often subclonal, include deletions, gains, and amplifications as well as monosomies, and the common ones include chromosome 1q gain or amplification, 1p deletion, 13q deletion or monosomy 13, and 17p deletion or monosomy 17. Some of these are associated with a poor outcome, while others may ameliorate the negative impact of high-risk abnormalities (Figure 2). These abnormalities have been incorporated into the disease-staging systems currently in use.9,10 While these abnormalities individually do not dictate the choice of a specific drug, the presence of high-risk characteristics influence the overall treatment strategy. However, this will likely change as we get more targeted agents.

The next major determinant of treatment selection is age and functional status or frailty.11,12 Age remains an easily assessable metric but a poor indicator of the ability of an individual to withstand the intensity of a given myeloma therapy. Given the median age at diagnosis of the late sixties, many patients present with significant comorbidities as well as several social determinants of health that can influence their disease presentation as well as the ability to tolerate the treatments. Several different frailty scores are in use currently, and any of them can be used to identify frail patients. These characteristics and patient preferences determine the intensity of the initial regimen and the ability to subsequently utilize some effective therapies like autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT).

Initial treatment selection and disease control

The goal of initial treatment in MM is to achieve rapid control of the disease, which can, in turn, lead to a reversal of many of the symptoms and complications related to the disease at presentation and reduce the risk of early mortality associated with uncontrolled disease while minimizing treatment-related toxicity. This serves as the foundation for further consolidation therapy and long-term maintenance approaches designed to maximize the outcomes from the initial treatment strategy. Over the past 2 decades, the initial treatment approach has evolved but has primarily depended on effective agents such as proteasome inhibitors (PIs; bortezomib, carfilzomib, ixazomib), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs; thalidomide, lenalidomide), and, more recently, anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs; daratumumab, isatuximab) used in various combinations.4,13 During this period the treatments have slowly evolved from the use of a doublet that included either a PI or an IMiD along with dexamethasone to triplets that combined both a PI and an IMiD and, more recently, triplets that include an anti-CD38 MoAb with lenalidomide and quadruplets that add an anti-CD38 MoAb to the combination of PI and IMiD. Other regimens have utilized these effective agents in combination with traditional drugs, including alkylating agents. The use of multidrug combinations has resulted in deeper and more rapid responses to the initial therapy. The results from these different doublet, triplet, and quadruplet regimens are shown in Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Doublet regimens in randomized trials of newly diagnosed multiple myelomaa

| Trial . | Regimen . | Duration of treatment . | N . | ORR . | > = VGPR . | > = CR . | Median PFS (months) . | Median OS (months) . | Median follow up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT0005756426 NDMM | Td | Continued until progression/ toxicity | 235 | 63% | 15.8% | 7.7% - | 14.9 | NR (75.7% at 18 mo) | 18 |

| Placebo-dex | Continued until progression/ toxicity | 235 | 46% | 43.8% | 2.6% - | 6.5 | NR (71.1% at 18 mo) | ||

| IFM 2005-01 NCT0020068127 NDMM, age < = 65 years | VAD + ASCT + DCEP vs no consolidation | 4 cycles + ASCT +2 cycles consolidation vs no consolidation | 242 | 77.1% after ASCT | 37.2% after ASCT | 8.7% after ASCT - | 29.7 | NR (77.4% at 3 y) | 32.2 |

| Bd + ASCT + DCEP vs no consolidation | 240 | 80.3% after ASCT | 54.3% after ASCT | 16.1% after ASCT - | 36 | NR (81.4% at 3 y) | |||

| NCT0055192828 NDMM, age < = 65 years | Rd + MPR + R/no maintenance | Induction × 4 cycles + MPR × 6 cycles + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 132 | 90.9% | 62.9% | 18.2% - | 22.4 | NR, 65.3% at 4 y | 51.2 |

| Rd + ASCT + R/no maintenance | Induction × 4 cycles + ASCT + maintenance till progression/ tolerated | 141 | 92.9% | 58.9% | 23.4% - | 43 | NR, 81.6% at 4 y | ||

| RV-MM-EMN-441 NCT0109183129 NDMM, age < = 65 years | Rd + CRd + R/PR maintenance | Induction × 4 cycles + CRd × 6 cycles + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 129 | 89% | 50% | 12% - | 28.6 | NR, 73% at 4 y | 52 |

| Rd + ASCT + R/PR maintenance | Induction × 4 cycles + ASCT + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 127 | 91% | 54% | 13% - | 43.3 | NR, 86% at 4 y | ||

| NCT0109319630 NDMM | Rd + R vs PR maintenance | 9 cycles + maintenance till progression/ tolerated | 217 | 74% | 34% | 3% | 21 | NR, 58% at 4 y | 39 |

| MPR/CPR + R vs PR maintenance | 437 | MPR = 71%, CPR = 68% | MPR = 26%, CPR = 20.5% | MPR = 3%, CPR = 0.5% | 22 | NR, 67% at 4 y | |||

| FIRST NCT0068993620 NDMM | Rd until progression | Until progression/ tolerated | 535 | 81% | 48% | 22% | 26 | 59.1 | 67 |

| Rd × 18 cycles | 18 cycles | 541 | 79% | 47% | 20% | 21 | 62.3 | ||

| MPT | 12 cycles | 547 | 67% | 30% | 12% | 21.9 | 49.1 |

| Trial . | Regimen . | Duration of treatment . | N . | ORR . | > = VGPR . | > = CR . | Median PFS (months) . | Median OS (months) . | Median follow up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT0005756426 NDMM | Td | Continued until progression/ toxicity | 235 | 63% | 15.8% | 7.7% - | 14.9 | NR (75.7% at 18 mo) | 18 |

| Placebo-dex | Continued until progression/ toxicity | 235 | 46% | 43.8% | 2.6% - | 6.5 | NR (71.1% at 18 mo) | ||

| IFM 2005-01 NCT0020068127 NDMM, age < = 65 years | VAD + ASCT + DCEP vs no consolidation | 4 cycles + ASCT +2 cycles consolidation vs no consolidation | 242 | 77.1% after ASCT | 37.2% after ASCT | 8.7% after ASCT - | 29.7 | NR (77.4% at 3 y) | 32.2 |

| Bd + ASCT + DCEP vs no consolidation | 240 | 80.3% after ASCT | 54.3% after ASCT | 16.1% after ASCT - | 36 | NR (81.4% at 3 y) | |||

| NCT0055192828 NDMM, age < = 65 years | Rd + MPR + R/no maintenance | Induction × 4 cycles + MPR × 6 cycles + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 132 | 90.9% | 62.9% | 18.2% - | 22.4 | NR, 65.3% at 4 y | 51.2 |

| Rd + ASCT + R/no maintenance | Induction × 4 cycles + ASCT + maintenance till progression/ tolerated | 141 | 92.9% | 58.9% | 23.4% - | 43 | NR, 81.6% at 4 y | ||

| RV-MM-EMN-441 NCT0109183129 NDMM, age < = 65 years | Rd + CRd + R/PR maintenance | Induction × 4 cycles + CRd × 6 cycles + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 129 | 89% | 50% | 12% - | 28.6 | NR, 73% at 4 y | 52 |

| Rd + ASCT + R/PR maintenance | Induction × 4 cycles + ASCT + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 127 | 91% | 54% | 13% - | 43.3 | NR, 86% at 4 y | ||

| NCT0109319630 NDMM | Rd + R vs PR maintenance | 9 cycles + maintenance till progression/ tolerated | 217 | 74% | 34% | 3% | 21 | NR, 58% at 4 y | 39 |

| MPR/CPR + R vs PR maintenance | 437 | MPR = 71%, CPR = 68% | MPR = 26%, CPR = 20.5% | MPR = 3%, CPR = 0.5% | 22 | NR, 67% at 4 y | |||

| FIRST NCT0068993620 NDMM | Rd until progression | Until progression/ tolerated | 535 | 81% | 48% | 22% | 26 | 59.1 | 67 |

| Rd × 18 cycles | 18 cycles | 541 | 79% | 47% | 20% | 21 | 62.3 | ||

| MPT | 12 cycles | 547 | 67% | 30% | 12% | 21.9 | 49.1 |

Only regimens with any 1 of the PIs, IMiDs, or anti-CD38 MoAbs are included.

CPR, cyclophosphamide, prednisone, lenalidomide; CR, complete response; CVD, cardiovascular disease; dex, dexamethasone; EFS, event-free survival; MPR, melphalan, prednisone, lenalidomide; MPT, melphalan; NDMM, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; NR, not reached; ORR, overall response rate; PR, prednisone and lenalidomide; > = PR, partial response or better; R, lenalidomide; Rd, lenalidomide and dexamethasone; s/c, subcutaneous; V, bortezomib; VAD, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone; Vd, bortezomib and dexamethasone; VGPR, very good partial response.

Triplet regimens in randomized trials of newly diagnosed multiple myelomaa

| Trial . | Regimen . | Duration of treatment . | N . | ORR . | > = VGPR . | > = CR . | Median PFS (months) . | Median OS (months) . | Median follow-up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFM 2009 NCT0119106014 NDMM, age <65 y | VRd + ASCT + R maintenance | 3 cycles +2 cycles post ASCT + R maintenance × 1 y | 350 | 98% | 88% | 59% | 47.3 | NR, 60.2% at 8 y | 93 |

| VRd + R maintenance | 8 cycles + R maintenance × 1 y | 350 | 97% | 77% | 48% | 35.0 | NR, 62.2% at 8 years | ||

| DETERMINATION15 NCT01208662 NDMM, age <65 y | VRd + ASCT + R maintenance | 3 cycles +2 cycles post ASCT + R maintenance until progression | 365 | 98% | 83% | 47% | 67.5 | NR, 80.7% at 5 y | 76 |

| VRd + R maintenance | 8 cycles + R maintenance until progression | 357 | 95% | 80% | 42% | 46.2 | NR, 79.2% at 5 y | ||

| GIMEMA-MMY-3006 NCT0113448431 NDMM, age <65 y | VTd + double ASCT + VTd consolidation + dex maintenance | 3 cycles +2 cycles consolidation post double ASCT + dexamethasone maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 236 | 96% | 89% | 58% | 60 | NR | 124.1 |

| Td + double ASCT + Td consolidation + dex maintenance | 238 | 89% | 74% | 41% | 41 | 110 | |||

| GEM05menos65 NCT0046174732 NDMM, age <65 y | VTd + IFNα2b/T/ VT maintenance | 24-week induction + ASCT + maintenance × 3 years | 130 | 85% after induction | 60% after induction | 35% after induction | 56.1 | 60% at 8 y | 70.6 |

| Td + IFNα2b/T/ VT maintenance | 127 | 62% after induction | 29% after induction | 14% after induction | 29.2 | ||||

| VBMCP/VBAD/ bortezomib + IFNα2b/T/VT maintenance | 129 | 75% after induction | 36% after induction | 21% after induction | 39.9 | ||||

| NCT0091089733 NDMM, age <65 y | VTd + ASCT | 4 cycles + ASCT | 100 | 89% after ASCT | 74% after ASCT | 29% after ASCT | 26 | 32 | |

| Vd + ASCT | 99 | 86% after ASCT | 58% after ASCT | 31% after ASCT | 30 | - | |||

| IFM2013-04 NCT0156453734 NDMM, age <65 y | VCd | 4 cycles | 169 | 83.4% after induction | 56.2% after induction | 8.9% after induction | - | - | - |

| VTd | 4 cycles | 169 | 92.3% after induction | 66.3% after induction | 13% after induction | - | |||

| S0777 NCT0064422817 NDMM | VRd + Rd maintenance | 8 cycles + Rd maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 225 | 90.2% | 74.9% | 24.2% | 41 | NR | 84 |

| Rd + Rd maintenance | 6 cycles + Rd maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 235 | 78.8% | 53.2% | 12.1% | 29 | 69 | ||

| UPFRONT NCT0050741635 NDMM | Vd + V maintenance | 8 cycles induction +35 weeks maintenance | 168 | 73% | 37% | 3% | 14.7 | 49.8 | 42.7 |

| VTd + V maintenance | 167 | 80% | 51% | 4% | 15.4 | 51.5 | |||

| VMP + V maintenance | 167 | 70% | 41% | 4% | 17.3 | 53.1 | |||

| ENDURANCE NCT0186355025 NDMM | VRd + R maintenance | 12 cycles + maintenance × 2 years vs until progression/ tolerated | 542 | 84% after induction | 65% after induction | 15% after induction | 34.4 mo | NR, 84% at 3 y | 26 |

| KRd + R maintenance | 9 cycles + maintenance × 2 years vs until progression/ tolerated | 545 | 87% after induction | 74% after induction | 18% after induction | 34.6 mo | NR, 86% at 3 y | ||

| TOURMALINE-MM2 NCT0185052436 NDMM | IRd | 18 cycles + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 351 | 82.1% | 63% | 25.6% | 35.3 | NR | ~58 |

| Placebo-Rd | |||||||||

| 354 | 79.7% | 47.7% | 14.1% | 21.8 | NR | ||||

| MAIA NCT0225217237 NDMM | DRd | Treatment continued until progression/ tolerated | 368 | 92.9% | 81% | 51% | NR | NR | 56.2 |

| Rd | |||||||||

| 369 | 81.6% | 57% | 30% | 34.4 | NR |

| Trial . | Regimen . | Duration of treatment . | N . | ORR . | > = VGPR . | > = CR . | Median PFS (months) . | Median OS (months) . | Median follow-up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFM 2009 NCT0119106014 NDMM, age <65 y | VRd + ASCT + R maintenance | 3 cycles +2 cycles post ASCT + R maintenance × 1 y | 350 | 98% | 88% | 59% | 47.3 | NR, 60.2% at 8 y | 93 |

| VRd + R maintenance | 8 cycles + R maintenance × 1 y | 350 | 97% | 77% | 48% | 35.0 | NR, 62.2% at 8 years | ||

| DETERMINATION15 NCT01208662 NDMM, age <65 y | VRd + ASCT + R maintenance | 3 cycles +2 cycles post ASCT + R maintenance until progression | 365 | 98% | 83% | 47% | 67.5 | NR, 80.7% at 5 y | 76 |

| VRd + R maintenance | 8 cycles + R maintenance until progression | 357 | 95% | 80% | 42% | 46.2 | NR, 79.2% at 5 y | ||

| GIMEMA-MMY-3006 NCT0113448431 NDMM, age <65 y | VTd + double ASCT + VTd consolidation + dex maintenance | 3 cycles +2 cycles consolidation post double ASCT + dexamethasone maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 236 | 96% | 89% | 58% | 60 | NR | 124.1 |

| Td + double ASCT + Td consolidation + dex maintenance | 238 | 89% | 74% | 41% | 41 | 110 | |||

| GEM05menos65 NCT0046174732 NDMM, age <65 y | VTd + IFNα2b/T/ VT maintenance | 24-week induction + ASCT + maintenance × 3 years | 130 | 85% after induction | 60% after induction | 35% after induction | 56.1 | 60% at 8 y | 70.6 |

| Td + IFNα2b/T/ VT maintenance | 127 | 62% after induction | 29% after induction | 14% after induction | 29.2 | ||||

| VBMCP/VBAD/ bortezomib + IFNα2b/T/VT maintenance | 129 | 75% after induction | 36% after induction | 21% after induction | 39.9 | ||||

| NCT0091089733 NDMM, age <65 y | VTd + ASCT | 4 cycles + ASCT | 100 | 89% after ASCT | 74% after ASCT | 29% after ASCT | 26 | 32 | |

| Vd + ASCT | 99 | 86% after ASCT | 58% after ASCT | 31% after ASCT | 30 | - | |||

| IFM2013-04 NCT0156453734 NDMM, age <65 y | VCd | 4 cycles | 169 | 83.4% after induction | 56.2% after induction | 8.9% after induction | - | - | - |

| VTd | 4 cycles | 169 | 92.3% after induction | 66.3% after induction | 13% after induction | - | |||

| S0777 NCT0064422817 NDMM | VRd + Rd maintenance | 8 cycles + Rd maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 225 | 90.2% | 74.9% | 24.2% | 41 | NR | 84 |

| Rd + Rd maintenance | 6 cycles + Rd maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 235 | 78.8% | 53.2% | 12.1% | 29 | 69 | ||

| UPFRONT NCT0050741635 NDMM | Vd + V maintenance | 8 cycles induction +35 weeks maintenance | 168 | 73% | 37% | 3% | 14.7 | 49.8 | 42.7 |

| VTd + V maintenance | 167 | 80% | 51% | 4% | 15.4 | 51.5 | |||

| VMP + V maintenance | 167 | 70% | 41% | 4% | 17.3 | 53.1 | |||

| ENDURANCE NCT0186355025 NDMM | VRd + R maintenance | 12 cycles + maintenance × 2 years vs until progression/ tolerated | 542 | 84% after induction | 65% after induction | 15% after induction | 34.4 mo | NR, 84% at 3 y | 26 |

| KRd + R maintenance | 9 cycles + maintenance × 2 years vs until progression/ tolerated | 545 | 87% after induction | 74% after induction | 18% after induction | 34.6 mo | NR, 86% at 3 y | ||

| TOURMALINE-MM2 NCT0185052436 NDMM | IRd | 18 cycles + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 351 | 82.1% | 63% | 25.6% | 35.3 | NR | ~58 |

| Placebo-Rd | |||||||||

| 354 | 79.7% | 47.7% | 14.1% | 21.8 | NR | ||||

| MAIA NCT0225217237 NDMM | DRd | Treatment continued until progression/ tolerated | 368 | 92.9% | 81% | 51% | NR | NR | 56.2 |

| Rd | |||||||||

| 369 | 81.6% | 57% | 30% | 34.4 | NR |

Only regimens with any 2 of the PIs, IMiDs, or anti-CD38 MoAbs are included.

CPR, cyclophosphamide, prednisone, lenalidomide; CR, complete response; CVD, cardiovascular disease; Dara, daratumumab; dex, dexamethasone; DRd, daratumumab, lenalidomide, dexamethasone; EFS, event-free survival; I, ixazomib; IRd, ixazomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone; K, carfilzomib; KRd, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone; M, melphalan; MP, melphalan and prednisone; MPR, melphalan, prednisone, lenalidomide; MPT, melphalan, prednisone, thalidomide; NDMM, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; NR, not reached; ORR, overall response rate; PR, prednisone and lenalidomide; > = PR, partial response or better; R, lenalidomide; Rd, lenalidomide and dexamethasone; s/c, subcutaneous; V, bortezomib; VAD, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone; Vd, bortezomib and dexamethasone; VGPR, very good partial response; VMP, bortezomib, melphalan, prednisone; VMPT, bortezomib, melphalan, prednisone, thalidomide; VRd, bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone; VT, bortezomib and thalidomide; VTd, bortezomib, thalidomide, dexamethasone.

Quadruplet regimens in randomized trials of newly diagnosed multiple myelomaa

| Trial . | Regimen . | Duration of treatment . | N . | ORR . | > = VGPR . | > = CR . | Median PFS (months) . | Median OS (months) . | Median follow up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASSIOPEIA NCT0254138318 NDMM, age <65 y | VTd + ASCT + VTd consolidation + Dara vs no maintenance | 4 cycles induction + ASCT +2 cycles consolidation + maintenance × 2 years | 542 | 89.9% (100 days post ASCT) | 78% (100 days post ASCT) | 26% (100 days post ASCT) | NR (85% at 18 months) | NR | 18.8 |

| Dara-VTd + ASCT + Dara-VTd consolidation + Dara vs no maintenance | 543 | 92.6% (100 days post ASCT) | 83% (100 days post ASCT) | 39% (100 days post ASCT) | NR (93% at 18 months) | NR | |||

| Myeloma XI+ ISRCTN4940785238 NDMM | KRdc + ASCT + R/no maintenance | Minimum 4 cycles induction + ASCT + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 526 | 97.7% | 91.9% | 31% | NR | - | 34.5 |

| Rdc/Tdc + ASCT + R/no maintenance | 530 | 95.3% | 79.3% | 24% | 36.2 | - | |||

| GMMG-HD7 NCT0361773139 NDMM, age <70 y | VRd + ASCT | 3 cycles + ASCT | 329 | 83.6% after induction | 60.5% after induction | 21.6% after induction | - | - | - |

| Isa-VRd + ASCT | 331 | 90% after induction | 77.3% after induction | 24.2% after induction | - | - | |||

| PERSEUS19 NCT03710603 NDMM, age <70 y | VRd + ASCT + VRd consolidation + R maintenance | 4 cycles induction + ASCT +2 cycles consolidation + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 354 | 93.8% | 89.3% | 70.1% | NR, 67.7% at 4 years | NR | 47.5 |

| Dara-VRd + ASCT +Dara-VRd consolidation+ Dara R maintenance | 4 cycles induction + ASCT +2 cycles consolidation + maintenance until progression/ tolerated (Dara stopped if MRD− at 2 years) | 355 | 96.6% | 95.2% | 87.9% | NR, 84.3% at 4 y | NR | ||

| IMROZ21 NCT03319667 NDMM ≤80 y | VRd with R maintenance | 4 (6-week) cycles of VRd followed by 4-week cycles of Rd until disease progression | 181 | 92.3 | 82.9% | 64.1% | 45.2% at 5 y | NR | |

| Isatuximab VRd with Isa-R maintenance | 4 (6-week) cycles of Isa-VRd followed by 4-week cycles of Isa-Rd until disease progression | 264 | 91.3 | 89.1% | 74.7% | 63.2% at 5 y | NR | ||

| BENEFIT22 NCT04751877 NDMM ≤80 y | Isatuximab-Rd with Isa-R maintenance | Isa-Rd (cycle 1-12), Isa-R (cycle 13-18), Isa (cycle 19 to progression) | 135 | 78% (18 mo) | 70% (18 mo) | 31% (18 mo) | 80% at 2 y | NR | |

| Isatuximab VRd with Isa-R maintenance | Isa-Rd Bortezomib (cycle 1-12), Isa-R-bortezomib (cycle 13-18), Isa (cycle 19 to progression) | 135 | 85% (18 mo) | 82% (18 mo) | 58% (18 mo) | 91.5% at 2 y | NR |

| Trial . | Regimen . | Duration of treatment . | N . | ORR . | > = VGPR . | > = CR . | Median PFS (months) . | Median OS (months) . | Median follow up (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASSIOPEIA NCT0254138318 NDMM, age <65 y | VTd + ASCT + VTd consolidation + Dara vs no maintenance | 4 cycles induction + ASCT +2 cycles consolidation + maintenance × 2 years | 542 | 89.9% (100 days post ASCT) | 78% (100 days post ASCT) | 26% (100 days post ASCT) | NR (85% at 18 months) | NR | 18.8 |

| Dara-VTd + ASCT + Dara-VTd consolidation + Dara vs no maintenance | 543 | 92.6% (100 days post ASCT) | 83% (100 days post ASCT) | 39% (100 days post ASCT) | NR (93% at 18 months) | NR | |||

| Myeloma XI+ ISRCTN4940785238 NDMM | KRdc + ASCT + R/no maintenance | Minimum 4 cycles induction + ASCT + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 526 | 97.7% | 91.9% | 31% | NR | - | 34.5 |

| Rdc/Tdc + ASCT + R/no maintenance | 530 | 95.3% | 79.3% | 24% | 36.2 | - | |||

| GMMG-HD7 NCT0361773139 NDMM, age <70 y | VRd + ASCT | 3 cycles + ASCT | 329 | 83.6% after induction | 60.5% after induction | 21.6% after induction | - | - | - |

| Isa-VRd + ASCT | 331 | 90% after induction | 77.3% after induction | 24.2% after induction | - | - | |||

| PERSEUS19 NCT03710603 NDMM, age <70 y | VRd + ASCT + VRd consolidation + R maintenance | 4 cycles induction + ASCT +2 cycles consolidation + maintenance until progression/ tolerated | 354 | 93.8% | 89.3% | 70.1% | NR, 67.7% at 4 years | NR | 47.5 |

| Dara-VRd + ASCT +Dara-VRd consolidation+ Dara R maintenance | 4 cycles induction + ASCT +2 cycles consolidation + maintenance until progression/ tolerated (Dara stopped if MRD− at 2 years) | 355 | 96.6% | 95.2% | 87.9% | NR, 84.3% at 4 y | NR | ||

| IMROZ21 NCT03319667 NDMM ≤80 y | VRd with R maintenance | 4 (6-week) cycles of VRd followed by 4-week cycles of Rd until disease progression | 181 | 92.3 | 82.9% | 64.1% | 45.2% at 5 y | NR | |

| Isatuximab VRd with Isa-R maintenance | 4 (6-week) cycles of Isa-VRd followed by 4-week cycles of Isa-Rd until disease progression | 264 | 91.3 | 89.1% | 74.7% | 63.2% at 5 y | NR | ||

| BENEFIT22 NCT04751877 NDMM ≤80 y | Isatuximab-Rd with Isa-R maintenance | Isa-Rd (cycle 1-12), Isa-R (cycle 13-18), Isa (cycle 19 to progression) | 135 | 78% (18 mo) | 70% (18 mo) | 31% (18 mo) | 80% at 2 y | NR | |

| Isatuximab VRd with Isa-R maintenance | Isa-Rd Bortezomib (cycle 1-12), Isa-R-bortezomib (cycle 13-18), Isa (cycle 19 to progression) | 135 | 85% (18 mo) | 82% (18 mo) | 58% (18 mo) | 91.5% at 2 y | NR |

Only regimens with any 3 of the PIs, IMiDs, or anti-CD38 MoAbs are included.

CR, complete response; Dara, daratumumab; Dara-VTd, daratumumab, bortezomib, thalidomide, dexamethasone; dex, dexamethasone; Isa, isatuximab; Isa-VRd, isatuximab, bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone; NDMM, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; NR, not reached; ORR, overall response rate; R, lenalidomide; s/c, subcutaneous; V, bortezomib; VGPR, very good partial response; VRd, bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone.

The traditional approach had been to classify patients as transplant eligible or ineligible, often based on age and the presence of comorbidities, before deciding on the initial treatment regimen. This was primarily driven by the potential impact of initial therapy on the ability to collect stem cells, a valid concern when alkylating agents were a part of the initial treatments. As a result of this approach, the development of initial therapy has evolved on 2 parallel tracks, 1 for those considered eligible for ASCT, in which case patients received 4 to 6 cycles of induction therapy followed by ASCT used as consolidation. For those patients who were not considered eligible for ASCT, the treatment regimens over successive phase 3 trials initially explored the addition of novel therapies to melphalan-based regimens to demonstrate benefit. With subsequent trials demonstrating the ability to eliminate melphalan as part of the initial therapy, there has been increasing convergence in the type of initial treatment irrespective of the transplant eligibility. This, along with randomized trials demonstrating equivalent benefits in terms of overall survival (OS) for early or delayed ASCT, has allowed us to use similar therapies for initial control of the disease before making a decision on transplant eligibility.14,15 This has allowed providers to make a more accurate assessment of the ability of the patient to undergo ASCT and for patients to make an informed decision about the timing of ASCT, if they choose to pursue it.

For those patients who can potentially undergo an ASCT, the approach has been to increase the intensity of initial treatment to achieve rapid and deep control of the disease before proceeding to transplant. For these patients, the treatment regimens have evolved from a doublet to a triplet and eventually to a quadruplet. Initial studies demonstrated the superiority of the lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) combination as an effective initial therapy.16 Subsequently, bortezomib was added to Rd, and the triplet regimen was shown to improve progression-free survival (PFS) and OS when used as an initial therapy.17 The randomized trials that explored the use of ASCT as consolidation increasingly used the VRd combination as the induction therapy before transplant. More recently, several phase 2 and 3 trials demonstrated improved PFS outcomes associated with adding daratumumab.18,19 In contrast, in patients not considered fit for ASCT, Rd was compared with melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide and was shown to have improved PFS.20 Phase 3 trials initially explored triplets in this patient population, given the concern with tolerability of more intense therapies in older patients. The addition of daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone led to improved PFS and OS with these 3-drug regimens, making this the current standard treatment approach for these patients.18,19 More recently, 2 large phase 3 trials demonstrated the feasibility of using quadruplet regimens in an older population until the age of 80 years; both the IMROZ and BENEFIT trials demonstrated improved response rates and deeper response with the use of quadruplets compared with triplets, with the IMROZ trial demonstrating an improved OS as well.21,22

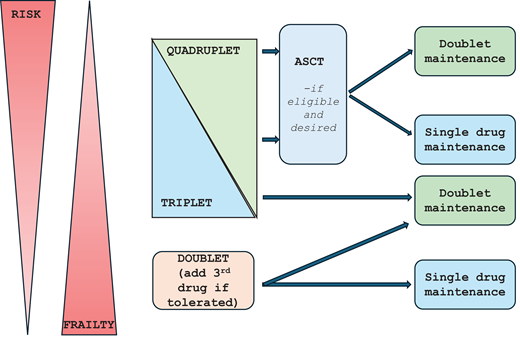

The choice between doublets, triplets, or quadruplets is increasingly made based on the patient's ability to tolerate the treatment while also considering the underlying genomic risk (Figure 3), fully acknowledging that these 2 parameters exist in a continuum.23,24 As a result, an accurate assessment of the patient's functional status at the time of diagnosis is key to making this decision. It is also important to keep in mind that in patients who are thought to be unable to tolerate intense therapy, control of the disease with a less intense regimen can often improve the functional status to a point where another drug can be added to the combination. Given the results from the phase 3 trials, most patients should receive at least a triplet consisting of 2 of these 3 classes of drugs plus dexamethasone, modified to the patient's tolerance. In patients in their late 80s and older, as well as those who are quite frail, a doublet can certainly be considered with the intent to add the third drug if their functional status improves with treatment. For most patients, the current standard approach is to use a quadruplet regimen containing an anti-CD38 MoAb, a PI, an IMiD, and dexamethasone for the initial treatment of MM. A triplet consisting of an anti-CD38 MoAbs and lenalidomide can be considered if the 4-drug combination cannot be tolerated or transplant is not considered an option for whatever reason. Recent phase 3 trials have demonstrated an equivalent benefit using isatuximab, another anti-CD 38 MoAb similar to daratumumab. Two randomized trials evaluated carfilzomib instead of bortezomib and did not demonstrate an improved survival outcome despite deeper responses, likely due to the increased toxicity associated with carfilzomib.25 However, phase 2 trials have utilized carfilzomib in combination with an anti-CD 38 MoAb, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone and have demonstrated deep responses and certainly remain an option if bortezomib cannot be used.

Approach to initial treatment selection in patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic MM accounting for frailty and risk.

Approach to initial treatment selection in patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic MM accounting for frailty and risk.

What if scenarios—alternate approaches

Several presenting characteristics might dictate an alternate approach or regimen for the initial treatment of MM. Renal insufficiency can be present in up to a third of the patients with newly diagnosed MM, with approximately 5% of patients requiring renal replacement therapy at least through the initial weeks after diagnosis. While lenalidomide can be used on patients with renal dysfunction, it can be difficult given their fluctuating renal function as well as the time it often takes to get this started in the inpatient setting. Given the importance of rapid disease control in patients with renal insufficiency, regimens such as daratumumab combined with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone have been used with good outcomes. The additive value of cyclophosphamide has not been specifically explored in this quadruplet regimen, though 1 phase 3 trial did not demonstrate the benefit of adding cyclophosphamide to bortezomib and dexamethasone. In these patients, cyclophosphamide should be replaced with lenalidomide after the initial cycle and once the renal function improves, as this regimen has been associated with better outcomes.

Another clinical scenario that can bring challenges includes patients who present with bulky extramedullary disease or plasma cell leukemia. Plasma cell leukemia, now defined as greater than or equal to 5% circulating plasma cells, can be associated with cytopenias that are often challenging when using current treatment regimens. For some of these patients, there may be a role for combinations of traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs for rapid disease control; regimens such as VDTPACE (bortezomib, dexamethasone, thalidomide, cisplatin, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide) have been used in this setting. After the initial disease debulking, these patients can switch to a more contemporary quadruplet regimen, as described above. While cytotoxic therapy agents such as anthracyclines can significantly impact the tumor, leading to rapid response induction, it is unclear whether this approach significantly impacts the long run. Other approaches have been explored in clinical trials like the OPTIMUM trial from the United Kingdom, where a 5-drug combination of cyclophosphamide added to DRVd has been used for high-risk patients.

Another setting where the quadruplet with lenalidomide can pose challenges is in those patients with concomitant light chain amyloidosis. Particularly with cardiac involvement, the use of lenalidomide has been associated with increased complications. In this setting, a combination of daratumumab and bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone can be used for initial disease control.

Maximizing the benefit—consolidation and maintenance

Once the disease is under good control, whether with the quadruplet, triplet, or doublet, maintenance therapy with or without additional consolidation represents the current approach. The ideal duration of therapy has not been well defined from randomized clinical trials, but ongoing trials explore either stopping treatment after a defined duration or using a response depth adapted duration of therapy to allow a sustained disease response. For those patients fit enough to undergo ASCT and who desire this procedure, 4 to 6 cycles of induction therapy can be followed by a single ASCT. Post transplant, patients are frequently placed on maintenance therapy, typically with the single agent lenalidomide, which is often continued until disease progression or until the patient is unable to tolerate the medication. Many of the recent phase 3 trials have explored adding daratumumab to lenalidomide, but the additional benefit remains undefined, and ongoing trials directly comparing DR with R will provide the definitive answer. In patients with high-risk disease, following ASCT a 2-drug maintenance regimen is typically used, most commonly the combination of bortezomib along with lenalidomide. For those patients who are not undergoing an ASCT, the triplet regimen is often continued for 9 to 12 months, at which time the dexamethasone is discontinued, and the dose and schedule of the remaining drugs are modified to allow for prolonged therapy.

Future directions

The initial treatment approach to myeloma continues to evolve rapidly with the advent of novel therapies, including immunotherapies such as bispecific antibodies. Ongoing clinical trials all explore achieving the deepest possible response with manageable toxicity to allow for prolonged disease control and, possibly, a defined duration of therapy in the future. This is being explored with novel immunotherapy, such as adding bispecific antibodies to the initial therapy, either as a replacement for 1 of the current drugs in the quadruplet or in addition to a doublet. Other therapies, such as CAR T and bispecific antibodies, are also being explored as potential consolidation, either as a replacement for or in addition to a stem cell transplant, depending upon the ability of the patient to undergo specific therapy as well as the underlying risks.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Shaji K. Kumar: consultancy: AbbVie, Amgen, ArcellX, Beigene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Carsgen, Epizyme, Glycostem, GSK, Janssen, K36, Menarini, Moderna, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche- Genentech, Sanofi, Takeda, Telogenomics, Trillium, Window Therapeutics, Antengene, Calyx, CVS Caremark, BD Biosciences; clinical trial support to institution: AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Carsgen, GSK, Gracell Bio, Janssen, Oricell, Roche-Genentech, Sanofi, Takeda, Telogenomics.

Off-label drug use

Shaji K. Kumar: Nothing to disclose.