TO THE EDITOR:

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a rare, indolent B-cell malignancy comprising <2% of all leukemias.1 Standard first-line therapy with purine nucleoside analogs, with or without rituximab, achieves durable remissions but carries significant and prolonged immunosuppressive risks.2 Infections remain a leading cause of death in HCL.3 For the ∼10% of patients presenting without symptoms, guidelines recommend active surveillance (AS), deferring treatment until cytopenias or clinical symptoms.2,4 AS in HCL consists of regular monitoring of blood counts and clinical assessments, delaying therapy to avoid unnecessary toxicity. Although data from other indolent lymphoid malignancies support this approach, HCL is biologically distinct, and no population-level survival data exist to guide clinical decision-making. We therefore performed a national, retrospective analysis to evaluate the safety of AS in HCL and to identify clinical factors that could guide its use.

We queried the National Cancer Database (NCDB) for patients diagnosed with HCL between 2010 and 2018 using histology code 9440. The NCDB is a clinical oncology database that contains hospital registry data collected from >1500 Commission on Cancer–accredited facilities in the United States and that captures ∼70% of all new invasive cancer diagnoses annually.5,6 Patients with known treatment status and survival data were included. Patients were categorized by NCDB-defined first therapy status. Up-front treatment included any systemic therapy initiated as part of the initial treatment plan. AS referred to cases for which the physician documented an intent to monitor without initiating treatment. No treatment was defined as cases in which treatment was declined by the patient or guardian, the patient died before treatment initiation, the physician recommended not to undergo treatment, or palliative care alone was advised. The demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors, including Charlson-Deyo comorbidity scores, were compared by treatment status using the χ2 test. Overall survival (OS) was estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves, in conjunction with log-rank tests. A multivariable Cox regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with OS. Age, gender, and insurance type differed between groups, and propensity score matching was done using a logistic regression model with a 1:5 ratio.

Among 5350 patients diagnosed with HCL in the NCDB between 2010 and 2018, the median follow-up was 59.1 months (range, 0.1-135.3). Of those, 41.6% of patients were diagnosed in the years 2010 to 2013, and 58.4% were diagnosed in the years 2014 to 2018. The median OS was not reached, and the 5-year OS rate was 85% (95% confidence interval, 0.84-0.86) for the entire cohort. Patients aged 60 years or older had significantly worse OS than those under 60 years (5-year OS, 95% vs 73%; P < .001). The OS outcomes did not differ significantly between male and female patients (5-year OS, 82% vs 85%; P = .094). Patients with government insurance had significantly worse OS than those with private insurance (5-year OS, 71% vs 94%; P < .001).

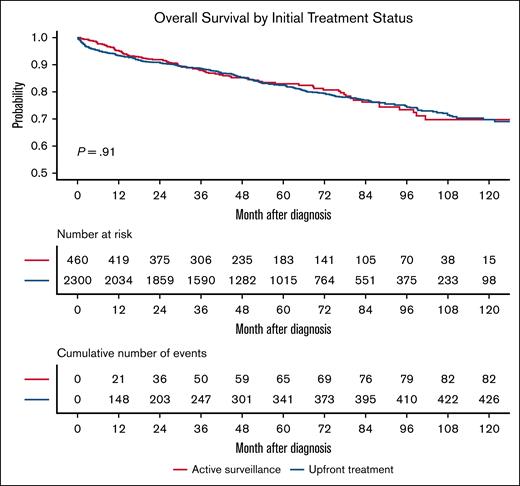

In terms of treatment, 535 patients (10%) underwent AS, 4230 (79.1%) received up-front treatment, and 585 (10.9%) were categorized as receiving no treatment. Patients managed with AS were significantly older with those over 60 years comprising 69.9% of the AS group and only 41.9% of the treated group (P < .001); they were also more frequently insured by Medicare (56.3% vs 33.7%; P < .001). AS patients also had higher comorbidity burdens with 16.4% having Charlson-Deyo scores of ≥2 vs only 10.8% in the treated cohort (P < .001). In the unmatched cohort, AS was associated with an inferior OS (5-year OS, 82% vs 87%; P < .001). After propensity score matching on age, gender, distance to facility, race, insurance type, income, education residential setting, and Charlson-Deyo score, 460 AS patients were matched to 2300 treated patients. The postmatching baseline characteristics were well balanced between the groups (all P > .1; Table 1). In the matched cohort, the OS was comparable between the groups (5-year OS, 80% in AS vs 83% in treated; P = .91; Figure 1).

Baseline characteristics of patients with HCL by treatment group before and after propensity score matching

| Demographic Characteristic . | All patients . | Propensity-matched patients . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS (n = 535) . | No treatment (N = 585) . | Up-front treatment (N = 4230) . | P value . | AS (n = 460) . | Up-front treatment (n = 2300) . | P value . | |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||||

| <60 | 161 (30.1) | 196 (33.5) | 2459 (58.1) | <.001 | 136 (29.6) | 770 (33.5) | .11 |

| ≥60 | 374 (69.9) | 389 (66.5) | 1771 (41.9) | 324 (70.4) | 1530 (66.5) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Female | 123 (23.0) | 145 (24.8) | 791 (18.7) | .02 | 102 (22.2) | 523 (22.7) | .86 |

| Male | 412 (77.0) | 440 (75.2) | 3439 (81.3) | 358 (77.8) | 1777 (77.3) | ||

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 500 (93.5) | 529 (90.4) | 3909 (92.4) | .14 | 434 (94.3) | 2152 (93.6) | .93 |

| African American | 12 (2.2) | 30 (5.1) | 145 (3.4) | 9 (2.0) | 59 (2.6) | ||

| Other/Unknown | 23 (4.3) | 26 (4.4) | 156 (3.7) | 17 (3.7) | 89 (3.9) | ||

| Charlson-Deyo score, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 454 (84.9) | 478 (81.7) | 3623 (85.7) | .18 | 389 (84.6) | 1947 (84.7) | .94 |

| ≥1 | 81 (15.1) | 107 (18.3) | 607 (14.3) | 71 (15.4) | 353 (15.3) | ||

| Insurance status, n (%) | |||||||

| Private | 240 (44.9) | 225 (38.5) | 2473 (58.4) | <.001 | 205 (44.6) | 1127 (49.0) | .32 |

| Government | 280 (52.3) | 320 (54.7) | 1488 (35.2) | 240 (52.2) | 1089 (47.3) | ||

| Not insured | 5 (0.9) | 26 (4.4) | 173 (4.1) | 5 (1.1) | 30 (1.3) | ||

| Unknown | 10 (1.9) | 14 (2.4) | 96 (2.3) | 10 (2.2) | 54 (2.3) | ||

| Demographic Characteristic . | All patients . | Propensity-matched patients . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS (n = 535) . | No treatment (N = 585) . | Up-front treatment (N = 4230) . | P value . | AS (n = 460) . | Up-front treatment (n = 2300) . | P value . | |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||||

| <60 | 161 (30.1) | 196 (33.5) | 2459 (58.1) | <.001 | 136 (29.6) | 770 (33.5) | .11 |

| ≥60 | 374 (69.9) | 389 (66.5) | 1771 (41.9) | 324 (70.4) | 1530 (66.5) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Female | 123 (23.0) | 145 (24.8) | 791 (18.7) | .02 | 102 (22.2) | 523 (22.7) | .86 |

| Male | 412 (77.0) | 440 (75.2) | 3439 (81.3) | 358 (77.8) | 1777 (77.3) | ||

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 500 (93.5) | 529 (90.4) | 3909 (92.4) | .14 | 434 (94.3) | 2152 (93.6) | .93 |

| African American | 12 (2.2) | 30 (5.1) | 145 (3.4) | 9 (2.0) | 59 (2.6) | ||

| Other/Unknown | 23 (4.3) | 26 (4.4) | 156 (3.7) | 17 (3.7) | 89 (3.9) | ||

| Charlson-Deyo score, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 454 (84.9) | 478 (81.7) | 3623 (85.7) | .18 | 389 (84.6) | 1947 (84.7) | .94 |

| ≥1 | 81 (15.1) | 107 (18.3) | 607 (14.3) | 71 (15.4) | 353 (15.3) | ||

| Insurance status, n (%) | |||||||

| Private | 240 (44.9) | 225 (38.5) | 2473 (58.4) | <.001 | 205 (44.6) | 1127 (49.0) | .32 |

| Government | 280 (52.3) | 320 (54.7) | 1488 (35.2) | 240 (52.2) | 1089 (47.3) | ||

| Not insured | 5 (0.9) | 26 (4.4) | 173 (4.1) | 5 (1.1) | 30 (1.3) | ||

| Unknown | 10 (1.9) | 14 (2.4) | 96 (2.3) | 10 (2.2) | 54 (2.3) | ||

Overall Survival in propensity score–matched patients with HCL by initial treatment strategy. Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing patients managed with AS (n = 460) and those treated at diagnosis (n = 2300) after 1:5 propensity score matching. No significant difference in OS was observed between groups (P = .91).

Overall Survival in propensity score–matched patients with HCL by initial treatment strategy. Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing patients managed with AS (n = 460) and those treated at diagnosis (n = 2300) after 1:5 propensity score matching. No significant difference in OS was observed between groups (P = .91).

This analysis represents the largest population-based study to date that evaluated AS in HCL. The unadjusted survival was worse among patients managed with AS, largely because of older age, higher comorbidity scores, and socioeconomic differences in this group. The demographic profile of patients selected for AS provides insight into real-world clinical practice with clinicians seeming to reserve AS for older patients and those with greater comorbidities in recognition that these populations may face higher risks for treatment-related toxicity. Although the unadjusted survival difference reflected these baseline differences, our propensity-adjusted analysis demonstrated that patients who underwent AS have survival outcomes that are comparable with those who were treated at diagnosis. These patterns may indicate that clinicians are applying AS in situations in which immediate treatment may not confer added survival benefit to avoid unnecessary toxicity in patients with competing health risks.

The previous recommendations for AS in HCL have been based largely on expert opinion and small, single-institution experiences without large-scale validation.2,4 Our findings support the safety of AS in asymptomatic patients with HCL and mirror patterns observed in other indolent lymphoid malignancies. It is important to note that the treatment landscape for HCL has improved over the study period. The use of rituximab in combination with purine analogs has become standard, and the introduction of targeted agents, such as BRAF/BTK inhibitors, offers new, more tolerable options for relapsed or refractory disease.4,7 Despite these advances, our study provides evidence that AS remains a viable and important management strategy for carefully selected asymptomatic patients, thereby enabling them to defer therapy and avoid even the relatively modest toxicities of modern treatments until clinically necessary. Although these findings are reassuring, it is important to acknowledge the well-recognized limitations of the NCDB, including the absence of disease-specific outcomes; the lack of detailed treatment regimens, including the inclusion of only the first treatment; the absence of data on progression or response; and limited handing of missing data or unmeasured confounders. Longitudinal data sets that include treatment beyond the first therapy would be better suited to assess the time to treatment and the sequence of decisions in patients. Future prospective studies and efforts to incorporate patients with HCL in clinical trials and disease-specific registries would further refine the role of AS in this population. In conclusion, AS is safe in appropriately selected patients with HCL and does not compromise the survival outcomes.

Contribution: V.M.R. and B.T.H. conceived of and designed the study; X.J., W.W., and V.M.R. performed the data analyses; V.M.R. and B.T.H. drafted the manuscript; and all authors interpreted the data, critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content, and approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Brian T. Hill, Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Ave, CA6, Cleveland, OH 44195; email: hillb2@ccf.org.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the author, Brian Hill (hillb2@ccf.org).