Key Points

Only ≤21% of patients achieved sustained response at week 52 with dapsone, with frequent early withdrawals because of adverse events.

Dapsone risk-benefit ratio as a second line for adult primary ITP should be carefully weighed when approved drugs are readily available.

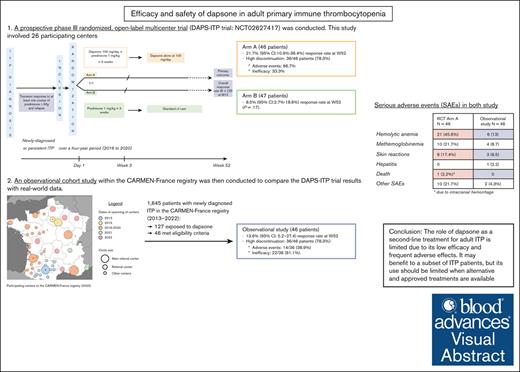

Visual Abstract

To assess efficacy and safety of dapsone in adult immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) and a real-world cohort study were performed. Participants were adults with primary ITP, transient response to corticosteroids with/without intravenous immunoglobulin, and a platelet count of ≤30 × 109/L (or ≤50 × 109/L with bleeding). Patients in the RCT were randomized in arm A (prednisone × 3 weeks + dapsone for 12 months) or arm B (prednisone alone). The observational study involved dapsone initiation at 100 mg/d with standard follow-up. The primary end point was the response rate (platelet count of >30 × 109/L and ≥2× baseline level) at 52 weeks, with the response rate at 24 weeks and adverse events as secondary end points. The RCT enrolled 93 patients (54.8% female), with median age of 48.5 years (46 years in arm A; and 47 years in arm B). In the intention-to-treat analysis, 78.3% of patients in arm A discontinued dapsone after a median of 4.6 weeks because of adverse events (66.7%) or lack of efficacy (33.3%). The response rate at week 52 was 21.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 10.9-36.4) in arm A vs 8.5% (95% CI, 2.7-18.6) in arm B (P = .17). The observational study, which was conducted after the end of the RCT, included 46 patients (52.2% female), median age of 50.7 years. Adverse events occurred in 30.4%, leading to discontinuation of dapsone in 23.9%, and 13.6% (95% CI 5.2-27.4) met the primary efficacy end point. Results from both studies showed an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio for the use of dapsone in adult primary ITP and suggest that, whenever available, second-line options should be used. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT02627417 and #NCT02877706.

Introduction

Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is a rare autoimmune disease leading to an accelerated platelet destruction and impaired platelet production, with an increased risk of bleeding when the platelet count is ≤30 × 109/L. First-line treatment of adult ITP relies on a short course of corticosteroids with/without IV immunoglobulin (IVIg) for severe bleeding manifestations. Most adults with newly diagnosed ITP initially respond to first-line treatment, but approximately two-thirds relapse within days or weeks of stopping corticosteroids.1 Thrombopoietin receptor agonists have become the preferred second-line option in many countries for adult patients with corticosteroid-dependent or persistent ITP.2 However, in countries in which thrombopoietin receptor agonists are unavailable or unaffordable, and in some European countries such as France and Italy, dapsone remains an off-label treatment option in this setting, and it appears as such in some ITP guidelines.3 Dapsone is an old and inexpensive drug characterized by antimicrobial/antiprotozoal properties with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects.4 In adult ITP, dapsone has shown a 40% to 60% efficacy rate in few uncontrolled retrospective studies,5-11 but its efficacy might be hampered by the occurrence of serious adverse events (SAEs) such as hemolytic anemia, methemoglobinemia, or severe cutaneous reactions,10 which may lead to treatment discontinuation in ∼15% of the patients.9,10 To date, there is, to our knowledge, no data based on a prospective randomized trial available supporting with a high level of evidence the efficacy and safety of dapsone in adult patients with ITP.

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy and safety of dapsone given as a second-line treatment for adult ITP. To achieve this objective, a randomized controlled study was conducted first, followed by an observational study within the CARMEN-France registry to provide real-world evidence.

Methods

Study design

A prospective phase 3, open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled trial (RCT; DAPS-ITP trial; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02627417) was conducted. This study involved 26 participating centers, mainly from university hospitals throughout France over a 4-year period (2016-2020; supplemental Table 1). An observational cohort study within the CARMEN-France registry was then conducted to compare the DAPS-ITP trial results with real-world data. This study was set up after the end of the RCT. The CARMEN-France registry is a prospective, multicenter, nationwide (54 participating centers in 2023) registry of adult patients with a new diagnosis of ITP in France, initiated in 2013.12

Eligibility criteria

DAPS-ITP

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the trial if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: (1) age of ≥18 years; (2) diagnosis of primary ITP; (3) previous transient response to corticosteroids with/without IVIg, defined by a platelet count of >30 × 109/L with at least a doubling of the baseline count; and (4) platelet count of ≤30 × 109/L at inclusion, or ≤50 × 109/L with bleeding symptoms. Patients with an age of ≥60 years had to have a normal bone marrow aspirate.

The main exclusion criteria were secondary ITP with severe bleeding manifestations and/or no previous response to corticosteroids with/without IVIg and a history of methemoglobinemia. Previous treatment for ITP other than corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulins (including rituximab and splenectomy) were also exclusion criteria for the study.

Details of the exclusion criteria are provided in the supplemental Appendix (supplemental Methods 1).

Observational study

Patients were selected if they were enrolled in the CARMEN-France ITP registry 12 between 1 June 2013 and 31 December 2022, with an exposure to dapsone and if they met the same inclusion criteria as for the DAPS-ITP trial. The patients included in both the CARMEN registry and the DAPS-ITP trial were excluded from the observational study.

Experimental plan

DAPS-ITP

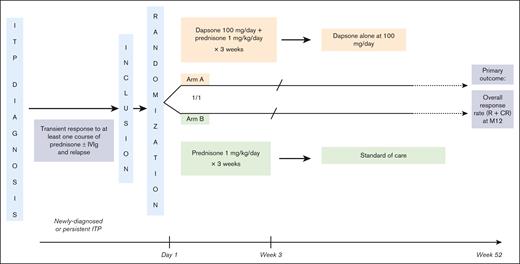

Eligible patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either the experimental arm (arm A: dapsone + prednisone) or the control arm (arm B: prednisone alone; Figure 1). Stopping rules and definitions of some specific dapsone-related SAEs are provided in supplemental Methods 2. Dapsone, which contains 200 mg of iron oxalate per tablet, generally causes dark discoloration of the stools, making blinding impossible. In addition, dapsone can cause some hemolysis, which precludes the feasibility and relevance of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. To limit the risk of classification bias, the outcome measure was objective (overall response), assessed by an independent, blinded expert.

Experimental plan of DAPS-ITP RCT. Eligible patients randomized to arm A received dapsone at 100 mg per day in combination with prednisone at a daily dose of 1 mg/kg for 2 weeks, then tapered, and stopped over 1 week for a total of 3 consecutive weeks. After prednisone withdrawal, patients in this arm continued to receive dapsone at the same dose for a total of 12 months unless they did not respond to treatment or in case of a dapsone-related AE graded ≥3. In that case, patients were classified as nonresponders and the subsequent treatment was chosen by the investigator at his/her discretion based on standard of care. Patients randomized to arm B received prednisone alone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for 2 weeks, then tapered, and stopped over a week for a total duration of 3 consecutive weeks. After this 3-week period, patients in arm B remained untreated and were monitored. In case of relapse, patients were classified as nonresponders and the subsequent treatment was chosen at the investigator’s discretion based on standard care. M12, Month 12; R, response; CR, complete response.

Experimental plan of DAPS-ITP RCT. Eligible patients randomized to arm A received dapsone at 100 mg per day in combination with prednisone at a daily dose of 1 mg/kg for 2 weeks, then tapered, and stopped over 1 week for a total of 3 consecutive weeks. After prednisone withdrawal, patients in this arm continued to receive dapsone at the same dose for a total of 12 months unless they did not respond to treatment or in case of a dapsone-related AE graded ≥3. In that case, patients were classified as nonresponders and the subsequent treatment was chosen by the investigator at his/her discretion based on standard of care. Patients randomized to arm B received prednisone alone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day for 2 weeks, then tapered, and stopped over a week for a total duration of 3 consecutive weeks. After this 3-week period, patients in arm B remained untreated and were monitored. In case of relapse, patients were classified as nonresponders and the subsequent treatment was chosen at the investigator’s discretion based on standard care. M12, Month 12; R, response; CR, complete response.

Observational study

Patients were followed-up from the date of dapsone initiation, and those who were lost of follow-up before week 52 were considered nonresponders.

Study outcomes

DAPS-ITP

The primary end point was the overall response rate (ORR) on dapsone (arm A) or off treatment (arm B) at week 52. ORR was defined by the achievement of response (defined by a platelet count of >30 × 109/L with at least a doubling of the baseline count) with/without complete response (CR), defined by a platelet count increase >100 × 109/L. Patients from both groups were considered as nonresponders if they received a rescue therapy (ie, corticosteroids with/without IVIg) for ITP beyond week 6 after inclusion and/or any other ITP treatment during the study period. The secondary end points were the ORR at week 24 and the rate of AE related to dapsone graded according to the common toxicity criteria for AEs. The details are provided in supplemental Methods 2.

Observational study

The primary outcome was the achievement of ORR at week 52 ± 4 weeks after dapsone initiation. Secondary outcomes were ORR at week 24 ± 4 weeks and the occurrence of adverse drug reactions with dapsone reported by the investigators of the registry between dapsone initiation and week 52.

Statistical analyses

All tests were 2-tailed and P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Main analysis was performed in the intention-to-treat population; a per-protocol analysis was also performed for the RCT. Additional information can be found in the online supplemental Appendix (supplemental Methods 3).

Ethics

DAPS-ITP

All patients gave informed signed consent. The study was approved by the institutional review board, namely the Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France III (approval number Am7051-1- 3308).

Observational study

Patients did not oppose to data collection nor to the conduction of such studies such as this one.12 The Toulouse University Hospital ethics committee gave approval to the registry in 2012 (approval number 27-0512). According to French law, authorization was obtained by the Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l'Information en matière de Recherche dans le domaine de la Santé (approval number 12.067) and by the Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés (approval number DE-2012-438).

Both studies were in accordance with the recommendations of the revised Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

DAPS-ITP

Population

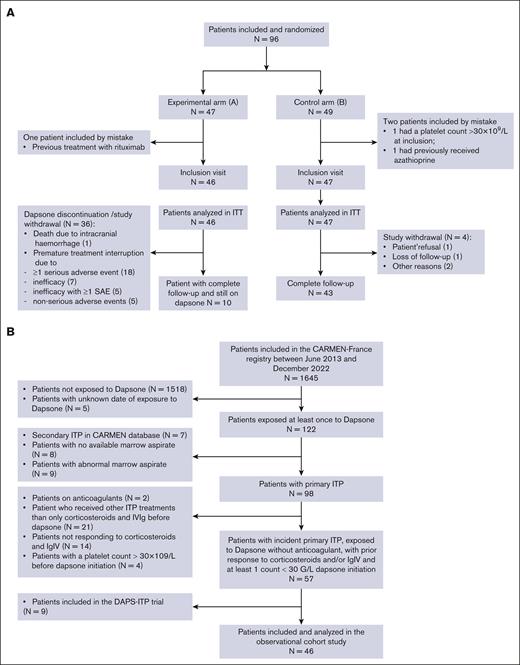

A total of 96 patients (47 in arm A and 49 in arm B) were initially randomized, among whom 3 (1 in arm A and 2 in arm B) were eventually excluded because they did not fulfill all the eligibility criteria (Figure 2A). In total, 93 patients (51 women [54.8%]), with a median age at ITP diagnosis of 48.5 (range, 30.0-64.5) years were enrolled. The median duration of ITP at inclusion was 0.3 years (range, 0.2-0.9). At the time of diagnosis, 46 patients (49.5%) presented with bleeding manifestations, and the median platelet count was 12.3 × 109/L (range, 7.0-31.5). Most patients (96.8%) were previously treated with prednisone at a daily dose of 1 mg/kg, with an ORR and a CR rate of 93.0% and 63.0%, respectively. Patients previously treated with dexamethasone (n = 16, 17.2%) had an ORR and a CR rate of 94.5% and 56.0%, respectively, whereas patients previously treated with IV methylprednisolone (n = 14, 15.1%) had an ORR and a CR rate of 100% and 43.0%, respectively. In addition, patients previously treated with IVIg (n = 35, 37.6%) at 1 to 2 g/kg had an ORR of 97.0% and a CR rate of 48.0% (Table 1; supplemental Table 2).

Flow charts. (A) Flowchart of the DAPS-ITP trial. (B) Flowchart of the observational cohort study. IgIV, Intravenous Immunoglobulin; ITT, intention to treat; SAE, serious adverse event.

Flow charts. (A) Flowchart of the DAPS-ITP trial. (B) Flowchart of the observational cohort study. IgIV, Intravenous Immunoglobulin; ITT, intention to treat; SAE, serious adverse event.

Patient main baseline characteristics

| Characteristics . | RCT arm A (dapsone), n = 46 . | RCT arm B (control) group), n = 47 . | Observational study cohort (dapsone), n = 46 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at ITP diagnosis, median (range), y | 48 (30-65) | 49 (30-62) | 51 (29-72) |

| Women, n (%) | 26 (57) | 25 (53) | 24 (52) |

| Platelet count at diagnosis, median, ×109/L (range) | 13 (7-32) | 11.5 (7-32) | 10.0 (5.0-23.0) |

| ITP duration, median (range), y | 0.27 (0.16-0.92) | 0.23 (0.15-0.92) | 0.22 (0.041-6.06)∗ |

| Bleeding symptoms at diagnosis, n (%) | 22 (49) | 24 (51) | 36 (78) |

| Previous treatment with corticosteroids, n (%) | 44 (96) | 47 (100) | 46 (100) |

| Previous treatment with IVIg, n (%) | 17 (37) | 18 (38) | 18 (39) |

| Characteristics . | RCT arm A (dapsone), n = 46 . | RCT arm B (control) group), n = 47 . | Observational study cohort (dapsone), n = 46 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at ITP diagnosis, median (range), y | 48 (30-65) | 49 (30-62) | 51 (29-72) |

| Women, n (%) | 26 (57) | 25 (53) | 24 (52) |

| Platelet count at diagnosis, median, ×109/L (range) | 13 (7-32) | 11.5 (7-32) | 10.0 (5.0-23.0) |

| ITP duration, median (range), y | 0.27 (0.16-0.92) | 0.23 (0.15-0.92) | 0.22 (0.041-6.06)∗ |

| Bleeding symptoms at diagnosis, n (%) | 22 (49) | 24 (51) | 36 (78) |

| Previous treatment with corticosteroids, n (%) | 44 (96) | 47 (100) | 46 (100) |

| Previous treatment with IVIg, n (%) | 17 (37) | 18 (38) | 18 (39) |

1 missing data.

Efficacy

Of 46 patients, 36 (78.3%) discontinued dapsone after a median time after treatment initiation of 4.6 weeks (range, 3.4-8.6). Lack of efficacy or AEs (described hereafter) were the reasons for discontinuation.

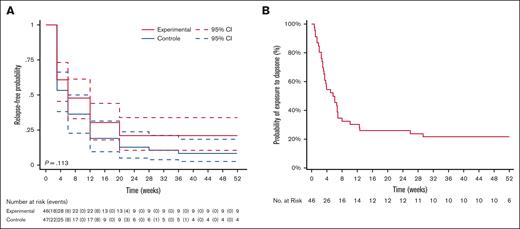

By intent-to-treat analysis, at week 52, the ORR in arm A was 21.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 10.9-36.4) compared with 8.5% (95% CI, 2.4-20.4) in arm B (P = .17; Figure 3A). At week 24, the ORR in arm A was 21.1% (95% CI, 10.6-33.9) compared with 12.8% (95% CI, 5.2-23.9) in arm B (P = .29).

Probability of dapsone discontinuation over time. (A) Probability of treatment discontinuation (experimental arm) or ITP relapse (control arm) over time in the DAPS-ITP trial (log-rank test). (B) Probability of dapsone discontinuation in the observational cohort study.

Probability of dapsone discontinuation over time. (A) Probability of treatment discontinuation (experimental arm) or ITP relapse (control arm) over time in the DAPS-ITP trial (log-rank test). (B) Probability of dapsone discontinuation in the observational cohort study.

By per-protocol analysis, at week 52, the ORR in arm A was 25.0% (95% CI, 11.1-41.8) compared with 8.5% (95% CI, 2.7-18.6) in arm B (P = .40). At week 24, the ORR in arm A was 25.0% (95% CI, 11.1-41.78) compared with 12.77% (95% CI, 5.2-23.9) in arm B (P = .57). At week 12, the response rate in the per-protocol population (n = 74) was 29.63% (95% CI, 14.06-47.03) in the experimental group (n = 27) compared with 36.17% (95% CI, 22.82-49.66) in the control group (N = 47; P = .88; supplemental Figure 1).

Safety

A total of 36 patients in arm A discontinued dapsone prematurely for the following reasons (Table 2): 19 patients (20.4%) discontinued treatment because of 1 or multiple SAEs; a total of 35 SAEs were reported in this group, the most common being hemolytic anemia, methemoglobinemia, and dapsone-induced rash. One death due to intracranial hemorrhage occurred in arm A. The patient initially achieved a response on prednisone + dapsone and then had a sudden drop of the platelet count after prednisone discontinuation leading to a fatal intracranial hemorrhage on day 26 after inclusion. No deaths were reported in arm B. Seven patients discontinued because of inefficacy alone, with no related SAEs. Five patients discontinued because of inefficacy associated with at least 1 SAE, for a total of 8 SAEs in this subgroup. Five patients discontinued because of nonserious AEs.

SAEs

| Type of SAE . | RCT arm A (dapsone), n = 30 patients (with 50 events/46 patients) . | Observational study cohort, n = 14 patients (with 16 events/46 patients) . |

|---|---|---|

| Hemolytic anemia∗ | 21 (45.6)/4 (8.7)/55 d | 6 (13) |

| Methemoglobinemia∗ | 10 (21.7)/5 (10.9)/21 d | 4 (8.7) |

| Drug-related skin reactions∗ | 8 (17.4)/3 (6.5)/24 d | 3 (6.5) |

| Hepatitis, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.2) |

| Death, n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 0 |

| Other SAEs, n (%)/n requiring treatment cessation (%) | 10 (21.7)/6 (13.0)† | 2 (4.3) |

| Type of SAE . | RCT arm A (dapsone), n = 30 patients (with 50 events/46 patients) . | Observational study cohort, n = 14 patients (with 16 events/46 patients) . |

|---|---|---|

| Hemolytic anemia∗ | 21 (45.6)/4 (8.7)/55 d | 6 (13) |

| Methemoglobinemia∗ | 10 (21.7)/5 (10.9)/21 d | 4 (8.7) |

| Drug-related skin reactions∗ | 8 (17.4)/3 (6.5)/24 d | 3 (6.5) |

| Hepatitis, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.2) |

| Death, n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 0 |

| Other SAEs, n (%)/n requiring treatment cessation (%) | 10 (21.7)/6 (13.0)† | 2 (4.3) |

Number (%)/number of patients requiring treatment cessation (%)/median time to onset (days)

Including 1 case of agranulocytosis and 1 cerebral vein thrombosis.

Additionally, 6 other patients experienced at least 1 SAE (a total of 7 events) after week 6 that did not necessitate discontinuation. These events included 5 cases of hemolytic anemia and 2 cases of rash unrelated to dapsone.

Observational study

Population

Of 1645 patients with a newly diagnosed ITP enrolled in the CARMEN-France registry between June 2013 and December 2022, 127 were exposed to dapsone, and 46 patients fulfilled eligibility criteria (Figure 2B). The median age at diagnosis was 50.7 (range, 29-72) years, and 52.2% were women. At diagnosis, 78.3% had bleeding symptoms and the median platelet count was 10 × 109/L (range, 5.0-23.0). The median time from disease onset to dapsone initiation was 2.6 (range, 0.5-72.7) months. All 46 patients had received corticosteroids and 39.1% had received IVIg before dapsone. In addition, 71.7% of patients were receiving concomitant treatment with corticosteroids and/or IVIg at the time of dapsone initiation (Table 1).

Efficacy

A total of 36 of 46 patients (78.3%) prematurely discontinued dapsone, 22 of 36 (61.1%) because of treatment inefficacy and need for an alternative treatment, whereas 14 of 36 patients (38.9%) stopped treatment because of safety concerns (description hereafter). The median time elapsed between dapsone initiation and treatment discontinuation was 3.57 weeks (range, 0.71-29.2). Of 46 patients, 10 were still receiving dapsone at week 52 ± 4 weeks (Figure 3B). Of these, 2 had missing platelet counts during the evaluation period for the primary end point. Consequently, these patients were excluded from the analysis. Two patients were receiving concomitant therapies and had not achieved a response at week 52 ± 4 weeks. The remaining 6 patients achieved a response at week 52 ± 4 weeks on dapsone alone. Therefore, 6 of 44 patients, that is, 13.6% (95% CI, 5.2-27.4) met the criteria for the primary outcome.

Regarding the secondary efficacy outcome, 12 of 46 patients were still receiving dapsone at week 24 ± 4 weeks. Of these, 5 had missing platelet counts during the evaluation period of the secondary outcome. Consequently, these patients were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 7 patients achieved a response by week 24 ± 4 weeks, including 6 on dapsone alone and 1 on dapsone + concomitant therapy. Therefore, 6 of 41 patients, that is, 14.6% (95% CI, 5.6-29.2) met the criteria for the secondary outcome.

Safety

Sixteen AEs were reported in 14 patients (30.4%; Table 2), 2 of which were serious (1 case of hepatitis and 1 case of cutaneous adverse drug reaction). Of note, 13 other events were considered clinically significant, including 6 cases of hemolytic anemia, 4 cases of methemoglobinemia, and 3 cases of dapsone-induced skin rash. The AEs led to treatment discontinuation in all but 3 patients (2 with mild hemolytic anemia and 1 with fatigue). Importantly, all patients ultimately had a favorable clinical outcome.

Discussion

The DAPS-ITP trial showed a 52-week ORR of only 21.7% in the experimental arm. Moreover, 78.3% discontinued dapsone mainly because of SAEs (66.7%) and mostly within the first 6 weeks after treatment initiation. To ensure that this unexpectedly high and early discontinuation rate had not been favored by the design and the stringent safety rules of the trial, an observational cohort study was subsequently conducted. Based on these real-word data, the rate of adverse drug reactions was indeed lower (30.4%) than in DAPS-ITP, but the efficacy rate of dapsone at week 52 was also found to be unexpectedly low (13.6%) and treatment failure was the main reason for discontinuation.

The finding of almost half as many AEs in the observational study as in the RCT could be explained by the fact that both investigators and patients of the DAPS-ITP trial were warned of all potential side effects of the drug and patients were more closely monitored (especially, for example, for methemoglobinemia level) than usually done in real-world practice. The incidence of SAEs leading to dapsone discontinuation reported in the largest retrospective series from the literature is indeed <15%, with ∼7.3% of severe skin reactions including the dapsone-induced drug hypersensitivity syndrome with some genetic predisposition in some populations.9,13 No cases of dapsone-induced drug hypersensitivity syndrome occurred in the DAPS-ITP trial, but after a careful review of the data by an expert dermatologist, besides 3 definite cases (6%) of grade 3 dapsone–induced skin rash, 5 nonsevere and/or dapsone-unrelated skin rash also leading to treatment discontinuation were recorded. Despite being a frequent side-effect, reversible upon treatment discontinuation, dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia seldom lead to clinical manifestations such as cyanosis and dyspnea.14 In the DAPS-ITP trial, an increased level of methemoglobinemia lead to the discontinuation of dapsone in 5 asymptomatic patients. Furthermore, the occurrence of a mild hemolytic anemia, which has been associated with a greater efficacy in ITP in some studies,11 has contributed to premature treatment discontinuation in several patients in the DAPS-ITP trial.

Regarding efficacy, a Brazilian retrospective study on 122 patients with ITP (including 21 patients with secondary ITP and 4 children) treated with dapsone reported, in 2021, an ORR of 66%, including a CR rate of 24%. The median time to response was 31 days (Q1-Q3, 21-48 days), but after a median follow-up of 3.4 years, 89% of the patients discontinued dapsone.12 Among 81 patients who achieved an initial response, 43 (53%) maintained a treatment-free response, whereas 28 (34.5%) experienced a relapse. These results are clearly not in keeping with our findings and these discrepancies cannot be explained by the baseline characteristics or patient background, because similar response rates have also been previously reported in retrospective studies from France and Italy.5-8 One explanation could be that the efficacy of dapsone was overestimated in previous retrospective studies. In our observational cohort, lack of efficacy was the main reported reason for early discontinuation of dapsone (61% of cases). However, taking into account that the median time of exposure to dapsone before discontinuation was only of 3.57 weeks, we can hypothesize, based on the data from the literature,12 that a prolonged exposure to dapsone, under cover of a transient rescue therapy if needed, could have led to a higher ORR. Moreover, the trend toward efficacy in the DAPS-ITP trial could have probably been significant if more patients were included. In addition, our data cannot be extrapolated to secondary ITP, in which dapsone may be useful, because patients with secondary ITP were excluded.

One of the reasons for promoting the use dapsone in ITP is its very low cost, which makes it easily available worldwide.7 However, the low efficacy rate and the safety issues observed in our studies may raise indirect costs, associated with medical interventions for the management of ITP relapses, side effects, and lost workdays. Unfortunately, in our study, we were not able to identify some predicting factors of response at baseline that could be helpful for selecting patients with ITP who are more prone to benefit from the use of dapsone.

The main strength of our study is that it is, to the best of our knowledge, the first multicenter randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy and safety of dapsone as a second-line treatment for adult primary ITP. Furthermore, the results from this RCT were strengthened by real-word evidence from a multicenter prospective registry with comprehensive data collection, that has already demonstrated its robustness in several epidemiological and pharmaco-epidemiological studies.15,16 The concordance of efficacy results between our RCT and our observational study underscores the usefulness and relevance of registry-based studies, particularly when RCTs are difficult to conduct or when further confirmation is needed.

The open-label design of DAPS-ITP trial could be viewed as a limitation, but a double-blind, placebo-controlled design was actually hardly feasible for at least 2 reasons. First, the experimental treatment (ie, disulone, the only manufactured form of dapsone available in France) contains 200 mg of iron oxalate per tablet and usually causes dark coloration of the stools. In addition, because dapsone causes some degree of hemolysis, it would have been difficult to keep the study blind at least for the investigators. Conversely, the strict rules for reporting every AE may have contributed to an unexpectedly high rate of premature treatment discontinuation in the dapsone arm including patients who may have achieved a later response. In the observational study, the limitations were that the time of exposure to dapsone before assessing the response was too low in most patients, and that the CARMEN registry included nonstandardized timing for platelet count, resulting in some missing data for the assessment of the primary outcome. Moreover, some platelet count fluctuations may be observed on dapsone as with other ITP treatments and assessment of response was based on a single platelet count at week 52.

Conclusion

These results show that the place of dapsone as a second-line treatment for primary adult ITP is more limited than previously assessed in retrospective studies. Dapsone remains an affordable option, which might be useful for a subset of patients with ITP (potentially with nonsevere persistent ITP); in countries in which other treatments for ITP are approved and readily available, its use should be restricted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, investigators, and research assistants of the DAPS-ITP trial and CARMEN-France registry.

The DAPS-ITP trial has been promoted and founded by the Direction de la Recherche Clinique, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris.

Authorship

Contribution: M. Michel and G.M. conceived and designed the study; M. Michel, G.M., M.R., F.C.-P., and M.L. analyzed the data; M. Michel, G.M., and M.L. wrote the manuscript; M. Michel and G.M. are the guarantors of the study, had full access to all the data, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; all authors collected data, and critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.M. reports honoraria and research funding from Amgen; reports honoraria from Argenx; reports honoraria and research funding from Grifols, Novartis, and Sanofi; and reports honoraria from Sobi, Alpine, and Union Chimique Belge. S.A. reports honoraria from Amgen, Argenx, Grifols, Novartis, and Sanofi; and received research funding from Novartis. L.T. reports honoraria from Alexion and Sobi; and consulted for Eusapharma. J.F.V. consulted for Eusapharma. L.G. consulted for Eusapharma and Amgen. S.C. reports honoraria from Novartis. M. Mahevas reports honoraria from Novartis and Amgen; and received research funding from Sanofi. B.G. reports honoraria from Novartis, Amgen, Sobi, and Grifols. M. Michel received honoraria for consultancy with, and speakers’ fees from, Alexion, Grifols, Novartis, Sanofi, and Sobi. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marc Michel, Department of Internal Medicine and Clinical Immunology, Henri Mondor University Hospital, 1 Rue Gustave Eiffel, 94000 Créteil, France; email: marc.michel2@aphp.fr.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Marc Michel (marc.michel2@aphp.fr or moulis.g@chu-toulouse.fr).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.