Key Points

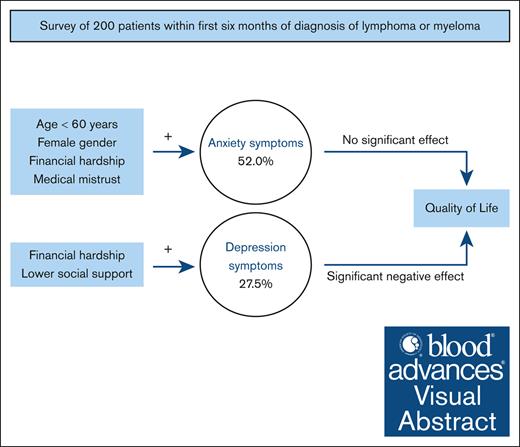

Over half of patients newly diagnosed with lymphoma or myeloma had clinically significant anxiety and/or depression symptoms.

Depression was associated with lower QOL, underscoring the need for psychological interventions for patients with lymphoma or myeloma.

Visual Abstract

Although lymphoma and myeloma confer physical and psychological burden, data are limited regarding anxiety and depression symptoms in affected patients. We conducted a survey between July 2021 and September 2022 to characterize anxiety and depression in a cohort of adult patients, within 6 months of a lymphoma or myeloma diagnosis. Clinically significant anxiety and depression symptoms were defined as scores of ≥8 on the corresponding subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. We assessed sociodemographic factors associated with anxiety/depression symptoms and examined the relationship between anxiety/depression symptoms and quality of life (QOL) in multivariable analyses. Our cohort included 200 patients (response rate, 74.9%), of whom 45.5% were female, and 55.5% were aged ≥60 years. Over half of the cohort (56.2%) had clinically significant anxiety and/or depression symptoms, with 52.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 44.9-59.1) meeting the cutoff for anxiety and 27.5% (95% CI, 21.6-34.3) for depression. Lower financial satisfaction (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 2.43; 95% CI, 1.25-4.78) and greater levels of medical mistrust (AOR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.10-4.02) were associated with higher odds of anxiety. Lower financial satisfaction (AOR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.07-4.30) and lower levels of social support (AOR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.42-6.00) were associated with higher odds of depression. Depression was associated with lower QOL (adjusted mean difference, −22.0; 95% CI, −28.1 to −15.9). More than half of patients newly diagnosed with lymphoma or myeloma experience clinically significant anxiety or depression symptoms, with associated detriment to their QOL. These findings underscore the need for systematic mental health screening and psychological interventions for this population.

Introduction

Lymphoma and myeloma are the 2 most common hematologic malignancies, with >125 000 new diagnoses in the United States in 2023.1 In addition to the physical symptoms that patients experience at diagnosis, they are vulnerable to substantial psychological burden. A new cancer diagnosis often incites a pervasive sense of uncertainty and emphasizes the threat of untimely death, which can result in anxiety and depression.2 Mental health disorders in patients with cancer have substantial negative and long-lasting impact, including poor quality of life (QOL),3 difficulty processing and recalling information,4 treatment delays,5 treatment nonadherence,6 and even increased mortality.7-9

Despite the potential psychological impact of lymphoma and myeloma, research on the psychological burden of cancer has largely focused on patients with solid malignancies. Patients with lymphoma or myeloma have disease presentations and management that are distinct from solid malignancies and may be particularly susceptible to developing anxiety or depression. For example, patients with aggressive lymphomas may present with high symptom burden requiring rapid institution of multiagent chemotherapy, which may heighten fear even when cure is possible. In contrast, patients with myeloma and indolent lymphomas are faced with information that their diagnosis is incurable, which may trigger symptoms of anxiety and depression. Moreover, while dealing with an incurable disease, some patients with indolent lymphoma are managed by watchful waiting without treatment, which is counterintuitive for many patients, and this approach can engender elevated levels of anxiety. Although recent publications have shed light on an increased prevalence of mental health disorders in patients with lymphoma and myeloma, most have relied on proxies such as psychotropic prescriptions or claims data rather than patient-reported data,10-15 or have largely focused on later stages of the disease trajectory rather than the early diagnosis period.16-19

Characterizing the psychological burden of patients with lymphoma or myeloma early on in their disease course is critical to develop and deploy effective psychosocial interventions that can be implemented in a timely manner for this population. Early interception of anxiety and depression symptoms in the lymphoma or myeloma disease trajectory may serve to mitigate downstream effects before they compound. We thus aimed to characterize the prevalence of self-reported anxiety and depression in a cohort of adults newly diagnosed with lymphoma or myeloma. We also sought to identify factors associated with increased risk of these disorders and the potential impact on QOL. We hypothesized that the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms would be high, and they would be associated with factors such as age, gender, financial hardship, medical mistrust, and social support.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a cross-sectional survey study at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA) of patients newly diagnosed with lymphoma or myeloma to characterize anxiety and depression, factors predictive of these symptoms, and the association of anxiety and depression with QOL. Patients who were aged ≥18 years and were within the first 6 months of their initial diagnosis of lymphoma or myeloma were eligible to participate. Between July 2021 and September 2022, eligible patients were identified from weekly clinic schedules and permission to approach was requested from each patient’s primary oncologist. After permission was obtained, potentially eligible patients were recruited remotely via telephone calls or in-person during scheduled clinic appointments. Individuals who agreed to participate in the study provided verbal informed consent. Consented participants had the option to either complete a web-based or paper version of the survey. After 1 week and 2 weeks of nonresponse to the initial survey, consented participants were sent reminder emails. If the survey was still not completed after 3 weeks of consent, nonrespondents received a telephone call reminder, after which no further contact was made. The Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center institutional review board approved the study methods.

Measurement selection

Our multidisciplinary research team consisting of hematologic oncologists, a nurse-scientist, clinical psychologists, and clinical psychology doctoral students compiled a survey consisting of previously published and validated instruments20-24 as well as new questions developed by our research team. We conducted pilot testing and individual cognitive debriefing interviews with 6 patients (3 with lymphoma and 3 with myeloma; 4 females and 2 males) within the first 6 months of their diagnosis to assess clarity of questions, potential burden of the compiled survey, and perceptions about length. The 6 participants completed the survey in an average of 12:24 minutes. Overall, participants reported that the survey was not burdensome, the length was appropriate, and the questions were clear. Some participants did note that some of the questions about finances may be perceived as intrusive but felt that it was still appropriate to include those questions because patients could skip questions as needed. We finalized the compiled survey based on these interviews.

The final compiled survey included items assessing anxiety and depression symptoms, social support, mental health stigma, perceptions of interventions to promote emotional coping, perceptions of health care and timing of diagnosis, medical mistrust, and QOL. We also collected self-reported demographic and financial information. Details regarding the measures included in the compiled survey are provided hereafter.

Key study measures

Demographic and clinical factors

Patients provided demographic information including age, gender, marital status, education, race, ethnicity, religious/spiritual practice, and monthly household income. In addition to their monthly household income, we also assessed financial hardship with 2 questions that have been validated previously25 and applied to patients with hematologic malignancies.26 The first was “How do your family finances usually work out at the end of the month?” with response options of “some money left over,” “just enough money,” and “not enough money.” The second question was “In general, how satisfied are you with your family’s present financial situation?” with response options on a 5-point Likert scale from “not at all” to “completely satisfied.” We collected clinical information from the electronic medical record including diagnosis type, date of diagnosis, and whether cancer-directed treatment had been initiated.

Anxiety and depression

We used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)20 to ascertain anxiety and depression symptoms. This validated self-administered questionnaire consists of 2 7-item subscales assessing anxiety and depression symptoms during the past week. Each subscale has a score range of 0 (no symptoms) to 21 (maximum symptoms). Although the HADS is a reliable measure of clinically significant anxiety and depression symptoms, it is not synonymous with a formal diagnosis of anxiety or depression because it does not include a clinical interview as required by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition. We used a score of ≥8 on the subscales of the HADS to indicate clinically significant anxiety or depression symptoms. This cutoff score was chosen based on existing data demonstrating an optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity when this cutoff score was compared with clinical interviews27 and prior use of this cutoff score in studies of patients with hematologic malignancies.28-30

Social support

We determined social support using the validated 8-item modified medical outcomes study–social support survey.23 The questions assess how often, on a 5-point Likert scale (“none of the time” to “all of the time”), patients have access to support that is emotional/informational, tangible, or affectionate, or a positive social interaction. Scores are assessed on a 0-to-100 scale, with higher scores indicating greater social support.

Medical mistrust

We measured medical mistrust by asking for respondents’ level of agreement with 5 questions on a validated “patient trust in the medical profession” scale,22 with response options from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Examples of statements on this scale include: “Sometimes doctors care more about what is convenient for them than about their patients’ medical needs,” and “You completely trust your doctor’s decisions about which medical treatments are best.” Scores are assessed on a 5-to-25 range scale, with lower scores indicating greater levels of medical mistrust.

QOL

We ascertained QOL using the global health status/QOL scale from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire.24 The global health status/QOL scale consists of 2 questions, in which participants are asked to rate their overall health and their overall QOL during the past week on a 7-point Likert scale of “very poor” to “excellent.” After linear transformation, the scale ranges in score from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better QOL.

Sample size determination

We based our sample size on the proportion of patients with lymphoma or myeloma meeting criteria for clinically significant anxiety (ie, HADS-A score of ≥8). We estimated that if ∼30% of respondents reported anxiety, with 200 completed surveys, we would be able to report this with a margin of error of ±6.35% (at a 0.95 confidence interval [CI]). We thus aimed to recruit participants until we reached this target sample size.

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were descriptively summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean (standard deviation) and median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. For measures of social support and medical mistrust, participants were grouped by whether scores were greater than vs less than or equal to the median values for the cohort. We determined the prevalence of clinically significant anxiety and depression symptoms along with 95% CIs. In univariable analysis, we determined sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with our key outcomes of (1) anxiety and (2) depression using χ2 tests. Variables that were statistically significant (P < .05) were then included in multivariable logistic regression models to determine variables independently associated with anxiety and depression. Multivariable logistic regression models were fit separately for anxiety and depression.

Next, we evaluated the potential relationship between clinically significant anxiety and depression symptoms with QOL. In univariable analysis, between-group differences in mean QOL were calculated with 95% CIs. A multivariable linear regression model for QOL was fit, in which the independent variables of interest were anxiety and depression, controlling for variables that were statistically significant (P < .05) in univariable analysis. Statistical significance was defined by 2-sided P <.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of 267 eligible patients approached, 200 completed the survey for an overall response rate of 74.9%. The median age of respondents was 61 years (interquartile range, 49-68), and 54.0% identified as men, 45.5% as women, and 0.5% as nonbinary. Most had lymphoma (80.5%). Eighty-five percent was White, 3.5% Black or African American, and 4.5% Asian, and, with respect to ethnicity, 5.5% was Hispanic or Latino. Of the total cohort, 37.9% had started chemotherapy before consenting to participate in this survey. The median time from diagnosis to survey consent was 42 days (interquartile range, 31-61.5). Known characteristics of nonrespondents did not differ significantly from those of respondents (age, P = .46; sex, P = .83; and blood cancer diagnosis, P = .44). Other characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1.

Patient, sociodemographic, and clinical characteristics of the full cohort

| . | n, nonmissing . | N = 200 . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 200 | |

| Mean (SD) | 58.0 (15.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 61.0 (49.0-68.0) | |

| Age group, y | 200 | |

| ≥60 | 111 (55.5%) | |

| <60 | 89 (44.5%) | |

| Gender identity | 200 | |

| Female | 91 (45.5%) | |

| Male | 108 (54.0%) | |

| Nonbinary | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Diagnosis | 200 | |

| Lymphoma | 161 (80.5%) | |

| Myeloma | 39 (19.5%) | |

| Marital status | 200 | |

| Divorced | 19 (9.5%) | |

| Living with unmarried partner | 11 (5.5%) | |

| Married | 137 (68.5%) | |

| Never married | 25 (12.5%) | |

| Separated | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Widowed | 7 (3.5%) | |

| Not listed | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Highest level of education achieved | 200 | |

| Eight grade or less | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Some high school, but did not graduate | 7 (3.5%) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 19 (9.5%) | |

| Some college or associate degree | 46 (23.0%) | |

| Bachelor degree | 54 (27.0%) | |

| Graduate degree | 73 (36.5%) | |

| Religion/spiritual practice | 200 | |

| Buddhist | 2 (1.0%) | |

| Christian | 130 (65.0%) | |

| Hindu | 4 (2.0%) | |

| Jewish | 15 (7.5%) | |

| Muslim | 0 (0.0%) | |

| None | 39 (19.5%) | |

| Not listed | 10 (5.0%) | |

| Has ever provided care for someone living with cancer | 200 | |

| Yes | 61 (30.5%) | |

| No | 139 (69.5%) | |

| Race | 200 | |

| Asian | 9 (4.5%) | |

| Black or African American | 7 (3.5%) | |

| Middle Eastern/North African | 3 (1.5%) | |

| Multiracial | 3 (1.5%) | |

| Native American, American Indian, or Alaskan Native | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0%) | |

| White | 170 (85.0%) | |

| Not listed | 7 (3.5%) | |

| Ethnicity | 199 | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 11 (5.5%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 188 (94.5%) | |

| Monthly household income, $ | 186 | |

| <1000 | 6 (3.2%) | |

| 1000-2999 | 27 (14.5%) | |

| 3000-4999 | 36 (19.4%) | |

| 5000-6999 | 29 (15.6%) | |

| ≥7000 | 88 (47.3%) | |

| Family finances at end of month | 190 | |

| Not enough money | 14 (7.4%) | |

| Just enough money | 50 (26.3%) | |

| Some money left over | 126 (66.3%) | |

| Satisfaction with family finances | 195 | |

| Not satisfied at all | 14 (7.2%) | |

| Slightly satisfied | 25 (12.8%) | |

| Moderately satisfied | 54 (27.7%) | |

| Very satisfied | 56 (28.7%) | |

| Completely satisfied | 46 (23.6%) | |

| Social support score (0-100)∗ | 200 | |

| Mean (SD) | 82.7 (19.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 89.1 (75.0-100.0) | |

| Social support score | 199 | |

| Greater than median (higher levels of support) | 100 (50.3%) | |

| Less than or equal to median (lower levels of support) | 99 (49.7%) | |

| Has a primary caregiver | 199 | |

| Yes | 180 (90.5%) | |

| No | 19 (9.5%) | |

| Chemotherapy started before study consent | 198 | |

| Yes | 75 (37.9%) | |

| No | 123 (62.1%) | |

| Days from start of chemotherapy to consent | 74 | |

| Mean (SD) | 21.5 (19.6) | |

| Median (IQR) | 13.5 (7.3-33.0) | |

| Days from diagnosis to consent | 199 | |

| Mean (SD) | 47.8 (24.7) | |

| Median (IQR) | 42.0 (31.0-61.5) | |

| Medical mistrust score† | 199 | |

| Greater than median (lower levels of mistrust) | 87 (43.7%) | |

| Less than or equal to median (higher levels of mistrust) | 112 (56.3%) |

| . | n, nonmissing . | N = 200 . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 200 | |

| Mean (SD) | 58.0 (15.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 61.0 (49.0-68.0) | |

| Age group, y | 200 | |

| ≥60 | 111 (55.5%) | |

| <60 | 89 (44.5%) | |

| Gender identity | 200 | |

| Female | 91 (45.5%) | |

| Male | 108 (54.0%) | |

| Nonbinary | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Diagnosis | 200 | |

| Lymphoma | 161 (80.5%) | |

| Myeloma | 39 (19.5%) | |

| Marital status | 200 | |

| Divorced | 19 (9.5%) | |

| Living with unmarried partner | 11 (5.5%) | |

| Married | 137 (68.5%) | |

| Never married | 25 (12.5%) | |

| Separated | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Widowed | 7 (3.5%) | |

| Not listed | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Highest level of education achieved | 200 | |

| Eight grade or less | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Some high school, but did not graduate | 7 (3.5%) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 19 (9.5%) | |

| Some college or associate degree | 46 (23.0%) | |

| Bachelor degree | 54 (27.0%) | |

| Graduate degree | 73 (36.5%) | |

| Religion/spiritual practice | 200 | |

| Buddhist | 2 (1.0%) | |

| Christian | 130 (65.0%) | |

| Hindu | 4 (2.0%) | |

| Jewish | 15 (7.5%) | |

| Muslim | 0 (0.0%) | |

| None | 39 (19.5%) | |

| Not listed | 10 (5.0%) | |

| Has ever provided care for someone living with cancer | 200 | |

| Yes | 61 (30.5%) | |

| No | 139 (69.5%) | |

| Race | 200 | |

| Asian | 9 (4.5%) | |

| Black or African American | 7 (3.5%) | |

| Middle Eastern/North African | 3 (1.5%) | |

| Multiracial | 3 (1.5%) | |

| Native American, American Indian, or Alaskan Native | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0%) | |

| White | 170 (85.0%) | |

| Not listed | 7 (3.5%) | |

| Ethnicity | 199 | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 11 (5.5%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 188 (94.5%) | |

| Monthly household income, $ | 186 | |

| <1000 | 6 (3.2%) | |

| 1000-2999 | 27 (14.5%) | |

| 3000-4999 | 36 (19.4%) | |

| 5000-6999 | 29 (15.6%) | |

| ≥7000 | 88 (47.3%) | |

| Family finances at end of month | 190 | |

| Not enough money | 14 (7.4%) | |

| Just enough money | 50 (26.3%) | |

| Some money left over | 126 (66.3%) | |

| Satisfaction with family finances | 195 | |

| Not satisfied at all | 14 (7.2%) | |

| Slightly satisfied | 25 (12.8%) | |

| Moderately satisfied | 54 (27.7%) | |

| Very satisfied | 56 (28.7%) | |

| Completely satisfied | 46 (23.6%) | |

| Social support score (0-100)∗ | 200 | |

| Mean (SD) | 82.7 (19.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 89.1 (75.0-100.0) | |

| Social support score | 199 | |

| Greater than median (higher levels of support) | 100 (50.3%) | |

| Less than or equal to median (lower levels of support) | 99 (49.7%) | |

| Has a primary caregiver | 199 | |

| Yes | 180 (90.5%) | |

| No | 19 (9.5%) | |

| Chemotherapy started before study consent | 198 | |

| Yes | 75 (37.9%) | |

| No | 123 (62.1%) | |

| Days from start of chemotherapy to consent | 74 | |

| Mean (SD) | 21.5 (19.6) | |

| Median (IQR) | 13.5 (7.3-33.0) | |

| Days from diagnosis to consent | 199 | |

| Mean (SD) | 47.8 (24.7) | |

| Median (IQR) | 42.0 (31.0-61.5) | |

| Medical mistrust score† | 199 | |

| Greater than median (lower levels of mistrust) | 87 (43.7%) | |

| Less than or equal to median (higher levels of mistrust) | 112 (56.3%) |

GED, general educational development; IQR, interquartile range.

Higher scores correspond to higher levels of social support.

Higher scores correspond to lower levels of medical mistrust.

Anxiety and depression and associated covariates

A total of 113 participants (56.5%) met the cutoff for clinically significant anxiety and/or depression, of whom 58 patients had anxiety alone, 9 patients had depression alone, and 46 patients met criteria for both. Overall, clinically significant anxiety was present in 104 patients (52.0%; 95% CI, 44.9-59.1) and 55 patients (27.5%; 95% CI, 21.6-34.3) had clinically significant depression. In univariable analysis examining factors associated with clinically significant anxiety, respondents aged <60 years were more likely to report anxiety symptoms (Table 2). Other factors associated with higher likelihood of clinically significant anxiety were female gender, single marital status, having a social support score below the median, lower financial satisfaction (ie, being only “moderately, slightly, or not satisfied” with finances), having “not enough money” or “just enough money” at the end of the month, and having a medical mistrust score below the median (ie, greater levels of medical mistrust). Receipt of chemotherapy before survey completion, race, and ethnicity were not significantly associated with anxiety symptoms. In adjusted multivariable analyses, factors that remained independently associated with higher odds of clinically significant anxiety included being aged <60 years (odds ratio [OR], 2.36; 95% CI, 1.23-4.59), female gender (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.09-4.14), lower financial satisfaction (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.25-4.78), and higher levels of medical mistrust (OR 2.09; 95% CI, 1.10-4.02).

Unadjusted and adjusted analyses of factors associated with clinically significant anxiety

| Characteristic∗ . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted, n = 192 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms present (HADS-A ≥ 8) n = 104 . | Anxiety symptoms absent (HADS-A < 8) n = 96 . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age group, y | <.001 | .010 | ||||

| ≥60 | 45 (40.5%) | 66 (59.5%) | — | — | ||

| <60 | 59 (66.3%) | 30 (33.7%) | 2.36 | 1.23-4.59 | ||

| Gender identity | .014 | .026 | ||||

| Not female | 48 (44.0%) | 61 (56.0%) | — | — | ||

| Female | 56 (61.5%) | 35 (38.5%) | 2.11 | 1.09-4.14 | ||

| Marital status | .001 | .14 | ||||

| Married/living with partner | 67 (45.3%) | 81 (54.7%) | — | — | ||

| Other | 37 (71.2%) | 15 (28.8%) | 1.78 | 0.83-3.95 | ||

| Highest level of education achieved | .55 | |||||

| Bachelor degree or higher | 64 (50.4%) | 63 (49.6%) | ||||

| Less than bachelor degree | 40 (54.8%) | 33 (45.2%) | ||||

| Religion/spiritual practice | .18 | |||||

| Has a religion/spiritual practice | 80 (49.7%) | 81 (50.3%) | ||||

| No religion/spiritual practice | 24 (61.5%) | 15 (38.5%) | ||||

| Race | .87 | |||||

| White | 88 (51.8%) | 82 (48.2%) | ||||

| Non-White | 16 (53.3%) | 14 (46.7%) | ||||

| Ethnicity | .44 | |||||

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 97 (51.6%) | 91 (48.4%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 7 (63.6%) | 4 (36.4%) | ||||

| Monthly household income, $ | .15 | |||||

| ≥7000 | 42 (47.7%) | 46 (52.3%) | ||||

| <7000 | 57 (58.2%) | 41 (41.8%) | ||||

| Family finances at end of month† | .014 | |||||

| Some money left over | 59 (46.8%) | 67 (53.2%) | ||||

| Just enough/not enough money left over | 42 (65.6%) | 22 (34.4%) | ||||

| Satisfaction with family finances | <.001 | .009 | ||||

| Completely/very satisfied | 39 (38.2%) | 63 (61.8%) | — | — | ||

| Moderately/slightly/not satisfied | 63 (67.7%) | 30 (32.3%) | 2.43 | 1.25-4.78 | ||

| Social support score | <.001 | .13 | ||||

| Greater than median (higher levels of support) | 40 (40.0%) | 60 (60.0%) | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (lower levels of support) | 64 (64.6%) | 35 (35.4%) | 1.69 | 0.86-3.30 | ||

| Chemotherapy started before study consent | .85 | |||||

| Yes | 38 (50.7%) | 37 (49.3%) | ||||

| No | 64 (52.0%) | 59 (48.0%) | ||||

| Medical mistrust score | .001 | .025 | ||||

| Greater than median (lower levels of mistrust) | 34 (39.1%) | 53 (60.9%) | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (higher levels of mistrust) | 70 (62.5%) | 42 (37.5%) | 2.09 | 1.10-4.02 | ||

| Characteristic∗ . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted, n = 192 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms present (HADS-A ≥ 8) n = 104 . | Anxiety symptoms absent (HADS-A < 8) n = 96 . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age group, y | <.001 | .010 | ||||

| ≥60 | 45 (40.5%) | 66 (59.5%) | — | — | ||

| <60 | 59 (66.3%) | 30 (33.7%) | 2.36 | 1.23-4.59 | ||

| Gender identity | .014 | .026 | ||||

| Not female | 48 (44.0%) | 61 (56.0%) | — | — | ||

| Female | 56 (61.5%) | 35 (38.5%) | 2.11 | 1.09-4.14 | ||

| Marital status | .001 | .14 | ||||

| Married/living with partner | 67 (45.3%) | 81 (54.7%) | — | — | ||

| Other | 37 (71.2%) | 15 (28.8%) | 1.78 | 0.83-3.95 | ||

| Highest level of education achieved | .55 | |||||

| Bachelor degree or higher | 64 (50.4%) | 63 (49.6%) | ||||

| Less than bachelor degree | 40 (54.8%) | 33 (45.2%) | ||||

| Religion/spiritual practice | .18 | |||||

| Has a religion/spiritual practice | 80 (49.7%) | 81 (50.3%) | ||||

| No religion/spiritual practice | 24 (61.5%) | 15 (38.5%) | ||||

| Race | .87 | |||||

| White | 88 (51.8%) | 82 (48.2%) | ||||

| Non-White | 16 (53.3%) | 14 (46.7%) | ||||

| Ethnicity | .44 | |||||

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 97 (51.6%) | 91 (48.4%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 7 (63.6%) | 4 (36.4%) | ||||

| Monthly household income, $ | .15 | |||||

| ≥7000 | 42 (47.7%) | 46 (52.3%) | ||||

| <7000 | 57 (58.2%) | 41 (41.8%) | ||||

| Family finances at end of month† | .014 | |||||

| Some money left over | 59 (46.8%) | 67 (53.2%) | ||||

| Just enough/not enough money left over | 42 (65.6%) | 22 (34.4%) | ||||

| Satisfaction with family finances | <.001 | .009 | ||||

| Completely/very satisfied | 39 (38.2%) | 63 (61.8%) | — | — | ||

| Moderately/slightly/not satisfied | 63 (67.7%) | 30 (32.3%) | 2.43 | 1.25-4.78 | ||

| Social support score | <.001 | .13 | ||||

| Greater than median (higher levels of support) | 40 (40.0%) | 60 (60.0%) | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (lower levels of support) | 64 (64.6%) | 35 (35.4%) | 1.69 | 0.86-3.30 | ||

| Chemotherapy started before study consent | .85 | |||||

| Yes | 38 (50.7%) | 37 (49.3%) | ||||

| No | 64 (52.0%) | 59 (48.0%) | ||||

| Medical mistrust score | .001 | .025 | ||||

| Greater than median (lower levels of mistrust) | 34 (39.1%) | 53 (60.9%) | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (higher levels of mistrust) | 70 (62.5%) | 42 (37.5%) | 2.09 | 1.10-4.02 | ||

ORs from multivariable logistic regression; ORs of >1 corresponding to increased odds of having clinically significant anxiety present.

Percentages are row percentages. Frequency counts do not sum to column totals because of missing data as follows: ethnicity (anxiety absent, n = 1); monthly household income (anxiety present, n = 5; anxiety absent, n = 9); family finances at end of month (anxiety present, n = 3; anxiety absent, n = 7); satisfaction with family finances (anxiety present, n = 2; anxiety absent, n = 3); social support score (anxiety absent, n = 1); chemotherapy status at study consent (anxiety present, n = 2); and medical mistrust score (anxiety absent, n = 1).

Only 7 of 64 participants with “just enough” or “not enough money left over” at the end of the month were completely/very satisfied with their family finances. Because of this overlap, “satisfaction with family finances” was included in the multivariable model, whereas “family finances at end of the month” was not included in the model.

In univariable analysis of factors associated with clinically significant depression, having a social support score below the median, lower financial satisfaction (ie, being only “moderately, slightly, or not satisfied” with finances), and having greater medical mistrust were significantly associated with a higher risk of depression (Table 3). Receipt of chemotherapy before survey completion, race, and ethnicity before survey completion were not significantly associated with depression symptoms. In multivariable analysis, social support score below the median (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.43-6.00) and lower financial satisfaction (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.07-4.30) conferred significantly higher odds of depression.

Unadjusted and adjusted analyses of factors associated with clinically significant depression

| Characteristic∗ . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted, n = 192 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression symptoms present (HADS-D ≥ 8) n = 55 . | Depression symptoms absent (HADS-D < 8) n = 145 . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age group, y | .88 | |||||

| ≥60 | 31 (27.9%) | 80 (72.1%) | ||||

| <60 | 24 (27.0%) | 65 (73.0%) | ||||

| Gender identity | >.99 | |||||

| Not female | 30 (27.5%) | 79 (72.5%) | ||||

| Female | 25 (27.5%) | 66 (72.5%) | ||||

| Marital status | .54 | |||||

| Married/living with partner | 39 (26.4%) | 109 (73.6%) | ||||

| Other | 16 (30.8%) | 36 (69.2%) | ||||

| Highest level of education achieved | .72 | |||||

| Bachelor degree or higher | 36 (28.3%) | 91 (71.7%) | ||||

| Less than Bachelor degree | 19 (26.0%) | 54 (74.0%) | ||||

| Religion/spiritual practice | .49 | |||||

| Has a religion/spiritual practice | 46 (28.6%) | 115 (71.4%) | ||||

| No religion/spiritual practice | 9 (23.1%) | 30 (76.9%) | ||||

| Race | .22 | |||||

| White | 44 (25.9%) | 126 (74.1%) | ||||

| Non-White | 11 (36.7%) | 19 (63.3%) | ||||

| Ethnicity | .30 | |||||

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 54 (28.7%) | 134 (71.3%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 1 (9.1%) | 10 (90.9%) | ||||

| Monthly household income, $ | .77 | |||||

| ≥7000 | 25 (28.4%) | 63 (71.6%) | ||||

| <7000 | 26 (26.5%) | 72 (73.5%) | ||||

| Family finances at end of month† | .61 | |||||

| Some money left over | 33 (26.2%) | 93 (73.8%) | ||||

| Just enough/not enough money left over | 19 (29.7%) | 45 (70.3%) | ||||

| Satisfaction with family finances | .002 | .032 | ||||

| Completely/very satisfied | 18 (17.6%) | 84 (82.4%) | — | — | ||

| Moderately/slightly/not satisfied | 35 (37.6%) | 58 (62.4%) | 2.12 | 1.07-4.30 | ||

| Social support score | <.001 | .003 | ||||

| Greater than median (higher levels of support) | 15 (15.0%) | 85 (85.0%) | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (lower levels of support) | 40 (40.4%) | 59 (59.6%) | 2.88 | 1.43-6.00 | ||

| Chemotherapy started before study consent | .98 | |||||

| Yes | 20 (26.7%) | 55 (73.3%) | ||||

| No | 33 (26.8%) | 90 (73.2%) | ||||

| Medical mistrust score | .024 | .20 | ||||

| Greater than median (lower levels of mistrust) | 17 (19.5%) | 70 (80.5%) | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (higher levels of mistrust) | 38 (33.9%) | 74 (66.1%) | 1.58 | 0.79-3.25 | ||

| Characteristic∗ . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted, n = 192 . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression symptoms present (HADS-D ≥ 8) n = 55 . | Depression symptoms absent (HADS-D < 8) n = 145 . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age group, y | .88 | |||||

| ≥60 | 31 (27.9%) | 80 (72.1%) | ||||

| <60 | 24 (27.0%) | 65 (73.0%) | ||||

| Gender identity | >.99 | |||||

| Not female | 30 (27.5%) | 79 (72.5%) | ||||

| Female | 25 (27.5%) | 66 (72.5%) | ||||

| Marital status | .54 | |||||

| Married/living with partner | 39 (26.4%) | 109 (73.6%) | ||||

| Other | 16 (30.8%) | 36 (69.2%) | ||||

| Highest level of education achieved | .72 | |||||

| Bachelor degree or higher | 36 (28.3%) | 91 (71.7%) | ||||

| Less than Bachelor degree | 19 (26.0%) | 54 (74.0%) | ||||

| Religion/spiritual practice | .49 | |||||

| Has a religion/spiritual practice | 46 (28.6%) | 115 (71.4%) | ||||

| No religion/spiritual practice | 9 (23.1%) | 30 (76.9%) | ||||

| Race | .22 | |||||

| White | 44 (25.9%) | 126 (74.1%) | ||||

| Non-White | 11 (36.7%) | 19 (63.3%) | ||||

| Ethnicity | .30 | |||||

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 54 (28.7%) | 134 (71.3%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 1 (9.1%) | 10 (90.9%) | ||||

| Monthly household income, $ | .77 | |||||

| ≥7000 | 25 (28.4%) | 63 (71.6%) | ||||

| <7000 | 26 (26.5%) | 72 (73.5%) | ||||

| Family finances at end of month† | .61 | |||||

| Some money left over | 33 (26.2%) | 93 (73.8%) | ||||

| Just enough/not enough money left over | 19 (29.7%) | 45 (70.3%) | ||||

| Satisfaction with family finances | .002 | .032 | ||||

| Completely/very satisfied | 18 (17.6%) | 84 (82.4%) | — | — | ||

| Moderately/slightly/not satisfied | 35 (37.6%) | 58 (62.4%) | 2.12 | 1.07-4.30 | ||

| Social support score | <.001 | .003 | ||||

| Greater than median (higher levels of support) | 15 (15.0%) | 85 (85.0%) | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (lower levels of support) | 40 (40.4%) | 59 (59.6%) | 2.88 | 1.43-6.00 | ||

| Chemotherapy started before study consent | .98 | |||||

| Yes | 20 (26.7%) | 55 (73.3%) | ||||

| No | 33 (26.8%) | 90 (73.2%) | ||||

| Medical mistrust score | .024 | .20 | ||||

| Greater than median (lower levels of mistrust) | 17 (19.5%) | 70 (80.5%) | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (higher levels of mistrust) | 38 (33.9%) | 74 (66.1%) | 1.58 | 0.79-3.25 | ||

ORs from multivariable logistic regression; ORs of >1 corresponding to increased odds of having clinically significant depression present.

Percentages are row percentages. Frequency counts do not sum to column totals due to missing data as follows: ethnicity (depression absent, n = 1); monthly household income (depression present, n = 4; depression absent, n = 10); family finances at end of month (depression present, n = 3; depression absent, n = 7); satisfaction with family finances (depression present, n = 2; depression absent, n = 3); social support score (depression absent, n = 1); chemotherapy status at study consent (depression present, n = 2); and medical mistrust score (depression absent, n = 1).

Only 7 of 64 participants with “just enough” or “not enough money left over” at the end of the month were completely/very satisfied with their family finances. Because of this overlap, “satisfaction with family finances” was included in the multivariable model, whereas “family finances at end of the month” was not included in the model.

Association of anxiety and depression with QOL

In unadjusted analysis, study participants experiencing clinically significant anxiety reported lower QOL scores than those without anxiety (mean, 62.4 [standard deviation (SD), 20.4] vs 74.7 [SD, 19.7]; P <.001). Similarly, individuals experiencing clinically significant depression had lower QOL scores than those not meeting the criteria for depression (50.6 [SD, 16.7] vs 75.1 [SD, 18.3]; P < .001). In a multivariable linear regression model that included clinically significant anxiety and depression, depression remained significantly associated with lower QOL, with a mean difference of 22 points lower for patients with vs without depression (95% CI, 28-16 points lower; Table 4).

Unadjusted and adjusted analyses of factors associated with QOL

| . | QOL . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted, n = 191 . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | Mean (SD) . | Mean difference . | 95% CI . | P value . | Mean difference . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Clinically significant anxiety | <.001 | .71 | ||||||

| Anxiety symptoms absent (HADS-A, <8) | 96 | 74.7 (19.7) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Anxiety symptoms present (HADS-A, ≥8) | 104 | 62.4 (20.4) | −12.3 | −17.9 to −6.7 | −1.1 | −6.6 to 4.5 | ||

| Clinically significant depression | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||

| Depression symptoms absent (HADS-D, <8) | 145 | 75.1 (18.3) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Depression symptoms present (HADS-D, ≥8) | 55 | 50.6 (16.7) | −24.5 | −30.0 to −18.9 | −22.0 | −28.1 to −15.9 | ||

| Age group, y | .32 | |||||||

| ≥60 | 111 | 67 (20.7) | — | — | ||||

| <60 | 89 | 69.9 (21.3) | 3.0 | −2.9 to 8.8 | ||||

| Gender identity | .54 | |||||||

| Not female | 109 | 69.1 (19.4) | — | — | ||||

| Female | 91 | 67.3 (22.7) | −1.8 | −7.7 to 4.0 | ||||

| Marital status | .52 | |||||||

| Married/living with partner | 148 | 68.9 (20.9) | — | — | ||||

| Other | 52 | 66.7 (21.3) | −2.2 | −8.9 to 4.5 | ||||

| Highest level of education achieved | .83 | |||||||

| Bachelor degree or higher | 127 | 68.1 (19.5) | — | — | ||||

| Less than Bachelor degree | 73 | 68.7 (23.3) | 0.7 | −5.4 to 6.7 | ||||

| Religion/spiritual practice | .040 | .006 | ||||||

| Has a religion/spiritual practice | 161 | 69.8 (21) | — | — | — | — | ||

| No religion/spiritual practice | 39 | 62.2 (19.8) | −7.6 | −14.9 to −0.3 | −8.5 | −14.7 to −2.4 | ||

| Race | .070 | |||||||

| White | 170 | 69.4 (20.7) | — | — | ||||

| Non-White | 30 | 61.9 (21.7) | −7.5 | −15.6 to 0.6 | ||||

| Ethnicity | .91 | |||||||

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 188 | 68.2 (21) | — | — | ||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 11 | 67.4 (19.9) | −0.8 | −13.5 to 12.0 | ||||

| Monthly household income, $ | .090 | |||||||

| ≥7000 | 88 | 70.5 (20) | — | — | ||||

| <7000 | 98 | 65.4 (21.4) | −5.2 | −11.2 to 0.8 | ||||

| Family finances at end of month∗ | .003 | |||||||

| Some money left over | 126 | 71.6 (19.9) | — | — | ||||

| Just enough/not enough money left over | 64 | 62.3 (21.5) | −9.3 | −15.4 to −3.1 | ||||

| Satisfaction with family finances | <.001 | .004 | ||||||

| Completely/very satisfied | 102 | 74.5 (18.7) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Moderately/slightly/not satisfied | 93 | 61.4 (21.2) | −13.1 | −18.7 to −7.5 | −7.7 | −12.9 to −2.4 | ||

| Social support score | .002 | .97 | ||||||

| Greater than median (higher levels of support) | 100 | 72.6 (20.2) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (lower levels of support) | 99 | 63.7 (20.7) | −8.8 | −14.5 to −3.1 | 0.1 | −5.1 to 5.3 | ||

| Chemotherapy started before study consent | .28 | |||||||

| Yes | 75 | 66.6 (19.1) | — | — | ||||

| No | 123 | 69.9 (21.8) | 3.3 | −2.7 to 9.3 | ||||

| Medical mistrust score | .045 | .44 | ||||||

| Greater than median (lower levels of mistrust) | 87 | 71.6 (20.8) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (higher levels of mistrust) | 112 | 65.6 (20.8) | −6.0 | −11.8 to −0.1 | −2.0 | −7.2 to 3.1 | ||

| . | QOL . | Unadjusted . | Adjusted, n = 191 . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n . | Mean (SD) . | Mean difference . | 95% CI . | P value . | Mean difference . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Clinically significant anxiety | <.001 | .71 | ||||||

| Anxiety symptoms absent (HADS-A, <8) | 96 | 74.7 (19.7) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Anxiety symptoms present (HADS-A, ≥8) | 104 | 62.4 (20.4) | −12.3 | −17.9 to −6.7 | −1.1 | −6.6 to 4.5 | ||

| Clinically significant depression | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||

| Depression symptoms absent (HADS-D, <8) | 145 | 75.1 (18.3) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Depression symptoms present (HADS-D, ≥8) | 55 | 50.6 (16.7) | −24.5 | −30.0 to −18.9 | −22.0 | −28.1 to −15.9 | ||

| Age group, y | .32 | |||||||

| ≥60 | 111 | 67 (20.7) | — | — | ||||

| <60 | 89 | 69.9 (21.3) | 3.0 | −2.9 to 8.8 | ||||

| Gender identity | .54 | |||||||

| Not female | 109 | 69.1 (19.4) | — | — | ||||

| Female | 91 | 67.3 (22.7) | −1.8 | −7.7 to 4.0 | ||||

| Marital status | .52 | |||||||

| Married/living with partner | 148 | 68.9 (20.9) | — | — | ||||

| Other | 52 | 66.7 (21.3) | −2.2 | −8.9 to 4.5 | ||||

| Highest level of education achieved | .83 | |||||||

| Bachelor degree or higher | 127 | 68.1 (19.5) | — | — | ||||

| Less than Bachelor degree | 73 | 68.7 (23.3) | 0.7 | −5.4 to 6.7 | ||||

| Religion/spiritual practice | .040 | .006 | ||||||

| Has a religion/spiritual practice | 161 | 69.8 (21) | — | — | — | — | ||

| No religion/spiritual practice | 39 | 62.2 (19.8) | −7.6 | −14.9 to −0.3 | −8.5 | −14.7 to −2.4 | ||

| Race | .070 | |||||||

| White | 170 | 69.4 (20.7) | — | — | ||||

| Non-White | 30 | 61.9 (21.7) | −7.5 | −15.6 to 0.6 | ||||

| Ethnicity | .91 | |||||||

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 188 | 68.2 (21) | — | — | ||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 11 | 67.4 (19.9) | −0.8 | −13.5 to 12.0 | ||||

| Monthly household income, $ | .090 | |||||||

| ≥7000 | 88 | 70.5 (20) | — | — | ||||

| <7000 | 98 | 65.4 (21.4) | −5.2 | −11.2 to 0.8 | ||||

| Family finances at end of month∗ | .003 | |||||||

| Some money left over | 126 | 71.6 (19.9) | — | — | ||||

| Just enough/not enough money left over | 64 | 62.3 (21.5) | −9.3 | −15.4 to −3.1 | ||||

| Satisfaction with family finances | <.001 | .004 | ||||||

| Completely/very satisfied | 102 | 74.5 (18.7) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Moderately/slightly/not satisfied | 93 | 61.4 (21.2) | −13.1 | −18.7 to −7.5 | −7.7 | −12.9 to −2.4 | ||

| Social support score | .002 | .97 | ||||||

| Greater than median (higher levels of support) | 100 | 72.6 (20.2) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (lower levels of support) | 99 | 63.7 (20.7) | −8.8 | −14.5 to −3.1 | 0.1 | −5.1 to 5.3 | ||

| Chemotherapy started before study consent | .28 | |||||||

| Yes | 75 | 66.6 (19.1) | — | — | ||||

| No | 123 | 69.9 (21.8) | 3.3 | −2.7 to 9.3 | ||||

| Medical mistrust score | .045 | .44 | ||||||

| Greater than median (lower levels of mistrust) | 87 | 71.6 (20.8) | — | — | — | — | ||

| Less than or equal to median (higher levels of mistrust) | 112 | 65.6 (20.8) | −6.0 | −11.8 to −0.1 | −2.0 | −7.2 to 3.1 | ||

Mean differences (ie, β coefficients) from univariable and multivariable linear regression; mean differences of >0 correspond to better QOL.

Only 7 of 64 participants with “just enough” or “not enough money left over” at the end of the month were completely/very satisfied with their family finances. Because of this overlap, “satisfaction with family finances” was included in the multivariable model, whereas “family finances at end of the month” was not included in the model.

Discussion

In this large cohort of adults newly diagnosed with lymphoma or myeloma, more than half experienced clinically significant anxiety or depression, signifying a substantial psychological burden in this population. Given that individuals who reported financial hardship, lower social support, and higher levels of medical mistrust were more likely to experience anxiety or depression, it is essential that interventions targeting psychological symptoms address these potentially modifiable factors. Finally, the strong association between depression symptoms and lower QOL suggests that interventions that effectively address depression could substantially improve the lived experience of patients with lymphoma or myeloma.

The prevalence of anxiety symptoms in this cohort (52%) is higher than prior studies of patients with lymphoma and myeloma, whereas the prevalence of depression symptoms is similar.18,30-32 For example, a study of patients with multiple myeloma receiving first-line therapy reported an anxiety rate of ∼20%.30 Similarly, in a study based in the Netherlands of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, who were on average 4.7 years and 3.5 years from diagnosis, 24% and 17%, respectively, reported anxiety symptoms.18 The higher prevalence of anxiety in our study than the aforementioned study in the Netherlands may be reflective of the fact that we focused on newly diagnosed patients, with a median of 42 days from diagnosis to study enrollment. The time around a lymphoma or myeloma diagnosis is likely more anxiety-provoking as patients deal with the shock of their life-altering diagnosis without the benefit of several years to adjust like patients who are further into survivorship. Moreover, patients who are much later in their disease trajectory may experience lower levels of uncertainty and anxiety if they have completed treatment and are in remission compared with those who are newly diagnosed. The ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic during the time when this study was conducted may have also partly contributed to higher levels of anxiety reported by patients.33 Nonetheless, the substantial burden of anxiety and depression symptoms within the first 6 months of diagnosis is concerning, especially given data suggesting that for some patients, these symptoms can persist over time, regardless of the patient’s phase in their disease trajectory.18,30 Our findings highlight the urgent need for systematic mental health screening for patients newly diagnosed with lymphoma or myeloma and timely referral to appropriate psychological interventions. 34

The fact that lower social support conferred almost 3-times higher odds of experiencing depressive symptoms than those with perceived higher social support suggests that social support has a crucial role in buffering mental well-being. Adequate social support, with its multidimensional construct of emotional/informational, affectionate, and tangible help (eg, help with chores, meals, and travel to appointments) can bolster patients’ ability to cope adaptively with cancer.35 Indeed, a study of patients diagnosed with cancer demonstrated that patients expressed strong desire for several elements of social support, including companionship, empathy, home care support, and help with appointments.36 Given the strong relationship between social support and depression in this population, future research should focus on interventions that expand social support for patients in which it is lacking.

In addition to the importance of patients’ relationship with their social support system, the relationship that patients have with the health care system is essential for mental well-being. Our finding that patients with lymphoma and myeloma with higher levels of medical mistrust were more likely to experience anxiety symptoms is consistent with studies of patients with solid malignancies.37,38 The need to rely on the health care system in the setting of a life-threatening diagnosis of lymphoma or myeloma may be especially anxiety-provoking for patients with high levels of medical mistrust. Moreover, existing literature suggests that individuals from minoritized populations are more likely to have high levels of medical mistrust, which may compound health inequities.39 Accordingly, it is important that health care systems and hematologic oncologists pay increased attention to building trust with patients right from the initial oncology encounter. Practices such as empathetic clinician–patient communication and patient-centered care may help to build trust, and potentially reduce anxiety.

Financial hardship, as measured based on low satisfaction with finances, was the sole factor associated with significantly higher odds of both anxiety and depression. Cancer care is substantially more expensive compared with care for other chronic conditions and results in considerable financial toxicity for affected patients.40,41 Thus, the prospect of additional financial burden for patients who are already experiencing financial hardship at the outset of their lymphoma or myeloma diagnosis may further contribute to the development of anxiety and depression symptoms. Potential steps that have been proposed to mitigate cancer-related financial toxicity include screening for financial hardship, patient assistance programs, and financial navigation.42 Our findings suggest that effectively ameliorating financial toxicity may have a cascading effect on reducing the risk of anxiety and depression in patients with lymphoma or myeloma.

Consistent with studies of psychological symptoms in patients with solid malignancies,3 self-reported depression was associated with both a significant and clinically meaningful decrement in QOL among patients newly diagnosed with lymphoma or myeloma. This strong association indicates that psychological interventions would likely be of benefit, not only in alleviating anxiety and depression, but in improving patients’ overall QOL. Although most research on psychological interventions has focused on patients later in the disease trajectory (after treatment, near the end of life), several randomized controlled trials have found that these interventions significantly reduce anxiety and depression and improve QOL.43 These studies predominantly focused on women with breast cancer, and lacked gender or racial diversity; we thus need research to develop and test interventions for diverse populations of patients with blood cancers. Promising strategies for interventions draw from cognitive behavioral therapy, psychoeducation, relaxation, mindfulness, and values-based living,44 all of which can help patients to recognize their psychological symptoms, develop skills to effectively meet their goals despite these symptoms, and maintain a sense of purpose throughout their disease trajectory.

Our study has limitations. First, the setting of our study was in a single tertiary care center, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, although we obtained a high response rate and respondents did not differ significantly from nonrespondents in terms of age, sex, and diagnosis, it is possible that our analysis suffered from nonresponse and participation bias. Third, our survey may have been subject to social desirability bias, which may lead to an underestimation of the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms. Fourth, it is possible that clinicians caring for the patients who participated in this survey made referrals for psychological services, which may have attenuated symptoms and led to an underestimate of the proportion of patients with clinically significant symptoms in our study. Fifth, the limited diversity with respect to race and ethnicity in our sample hampered our ability to detect significant relationships between these factors and mental health. Future research that is sufficiently powered to examine the potential relationship between race/ethnicity and psychosocial burden among patients with lymphoma or myeloma is needed. Finally, given the cross-sectional design of this study, we lack information regarding whether symptoms of anxiety and depression predated diagnosis of cancer and we can only note an association between depression and QOL, but cannot claim causality.

Psychological symptoms for patients with hematologic malignancies have been historically underrecognized and thus, undertreated. Our analysis demonstrates that the psychological toll of lymphoma or myeloma is high, with most patients experiencing anxiety or depression symptoms early in their disease trajectory. In addition to the distressing nature of these symptoms, depression symptoms substantially worsen overall QOL. Taken together, these data underscore the urgent need to systematically screen patients newly diagnosed with lymphoma or myeloma for anxiety and depression symptoms, and to refer affected patients for appropriate psychological interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (U54 DF/HCC-UMB-CA156732; CA156734 [O.O.O. and L.R.]). O.O.O. was also supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (K08-CA218295).

Authorship

Contribution: O.O.O., T.F.G., T.A., A. Ying, A. Yang, and L.R. conceptualized and designed the study; A.M.C. performed data analysis; O.O.O. and L.R. drafted the work/manuscript; and all authors interpreted the data, critically revised the manuscript, and gave final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.Y. consults for One Huddle. O.O.O. has consulted for AstraZeneca. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Oreofe O. Odejide, Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; email: oreofe_odejide@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Oreofe O. Odejide (oreofe_odejide@dfci.harvard.edu).