Visual Abstract

TO THE EDITOR:

The complement system is an integral part of the innate immune system and plays a pivotal role in immune surveillance and homeostasis by clearing apoptotic cells and targeting microbial pathogens.1-3 Considering the prominent role of the complement system in various diseases, drugs targeting different complement proteins have been investigated and approved in recent years.4-8 However, based on their mechanism of action, complement inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of bacterial infections.9,10

All patients treated with complement inhibitors are required to be vaccinated against Neisseria meningitidis (Nm),5-8 whereas vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae (Sp) and Haemophilus influenzae (Hi) type B is required for those treated with pegcetacoplan, iptacopan, and danicopan.7,8,11 Nevertheless, meningococcal infections have been reported in patients despite vaccination.12,13 Furthermore, ex vivo data suggest that patients taking C5 inhibitors are not sufficiently protected against meningococcal serogroup B infections, despite vaccination.14,15

To optimize treatment of patients with complement inhibitors in the future and to evaluate the potential risk for bacterial infections, we investigated the effect of AMY-101 (anti-C3), eculizumab (anti-C5), ravulizumab (anti-C5), iptacopan (antifactor B), and danicopan (antifactor D) in different concentrations on the degree of complement inhibition, complement deposition, and bacterial killing in vitro.

First, we determined the alternative pathway (AP) activity and classical pathway (CP) activity for all complement inhibitors using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent–based assay. AP inhibitors iptacopan and danicopan selectively inhibited the AP in a dose-dependent manner with 50% inhibition (IC50) of 0.8 μg/mL and 0.08 μg/mL, respectively. No effect was found on CP activity (supplemental Figure 1), which was in line with previous studies.16,17

Eculizumab, ravulizumab, and AMY-101 inhibited both the AP and CP in a dose-dependent manner. IC50 values were 44.1 μg/mL (AP) and 24.8 μg/mL (CP) for eculizumab, 41.5 μg/mL (AP) and 32.7 μg/mL (CP) for ravulizumab, and 7.3 μg/mL (AP) and 21.4 μg/mL (CP) for AMY-101 (supplemental Figure 1). These results were generally consistent with previous studies, although some differences in IC50 values were observed, which could be explained by differences in the assays used.18-25 Important to note is that there remains some CP activity (∼15%) using AMY-101, whereas AP activity is completely blocked (supplemental Figure 1).

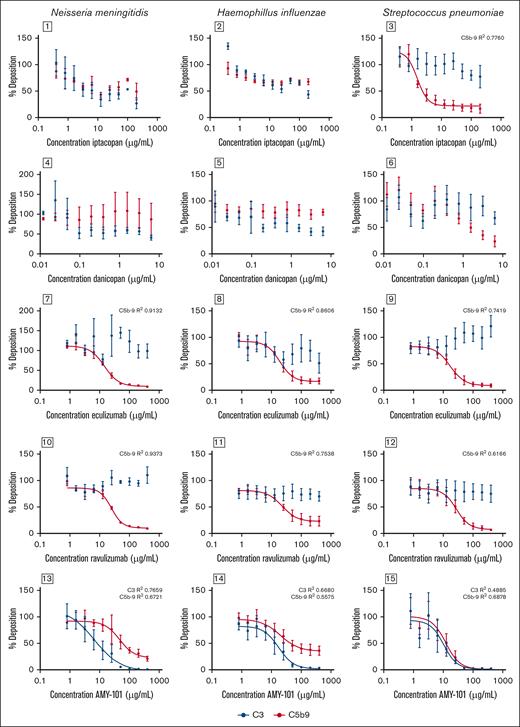

Next, we determined complement C3 and C5b-9 deposition on the bacterial surface of Nm, Hi, and Sp. Iptacopan inhibited the binding of C5b-9 on the surface of Sp in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 1.6 μg/mL, whereas the effects on the surface of Nm and Hi were more limited (Figure 1). For danicopan, no significant effect was measured on binding of complement C3 and C5b-9 to the bacterial surface of Nm and Hi and a small but nonsignificant effect was observed for Sp (Figure 2). Eculizumab and ravulizumab inhibited the binding of C5b-9 to the surface of Nm, Hi, and Sp in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 for eculizumab of 14.3 μg/mL, 18.9 μg/mL, and 17.0 μg/mL and an IC50 for ravulizumab of 24.7 μg/mL, 22.6 μg/mL, and 27.4 μg/mL, respectively (Figure 2). Maximal inhibition for eculizumab and ravulizumab was observed at concentrations >100 μg/mL, which corresponds with effective concentrations in vivo.5,26,27

Effect of iptacopan (antifactor B), danicopan (antifactor D), eculizumab (anti-C5), ravulizumab (anti-C5), and AMY-101 (anti-C3) on C3 and C5b-9 deposition on the surface of Np, Hi, and Sp. A twofold dilution series of complement inhibitors was made with pooled plasma. Bacteria (Nm, Hi, and Sp) were incubated in 10% plasma for 30 minutes at 37°C, and binding of C3 and C5b-9 was determined by flow cytometry. Binding of C3 is represented in black and binding of C5b-9 is represented in red (mean ± standard error of the mean; Nm: n = 3 for all inhibitors, except for iptacopan C5b-9 (n = 2); Hi: n = 3 for iptacopan, danicopan, and eculizumab, and n = 4 for AMY-101 and ravulizumab; and Sp: n = 4 for AMY-101, n = 5 for iptacopan and danicopan, n = 7 for eculizumab and n = 6 for ravulizumab). The results were normalized to pooled plasma without inhibitors. IC50 values were determined using variable-slope, 4-parameter nonlinear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism.

Effect of iptacopan (antifactor B), danicopan (antifactor D), eculizumab (anti-C5), ravulizumab (anti-C5), and AMY-101 (anti-C3) on C3 and C5b-9 deposition on the surface of Np, Hi, and Sp. A twofold dilution series of complement inhibitors was made with pooled plasma. Bacteria (Nm, Hi, and Sp) were incubated in 10% plasma for 30 minutes at 37°C, and binding of C3 and C5b-9 was determined by flow cytometry. Binding of C3 is represented in black and binding of C5b-9 is represented in red (mean ± standard error of the mean; Nm: n = 3 for all inhibitors, except for iptacopan C5b-9 (n = 2); Hi: n = 3 for iptacopan, danicopan, and eculizumab, and n = 4 for AMY-101 and ravulizumab; and Sp: n = 4 for AMY-101, n = 5 for iptacopan and danicopan, n = 7 for eculizumab and n = 6 for ravulizumab). The results were normalized to pooled plasma without inhibitors. IC50 values were determined using variable-slope, 4-parameter nonlinear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism.

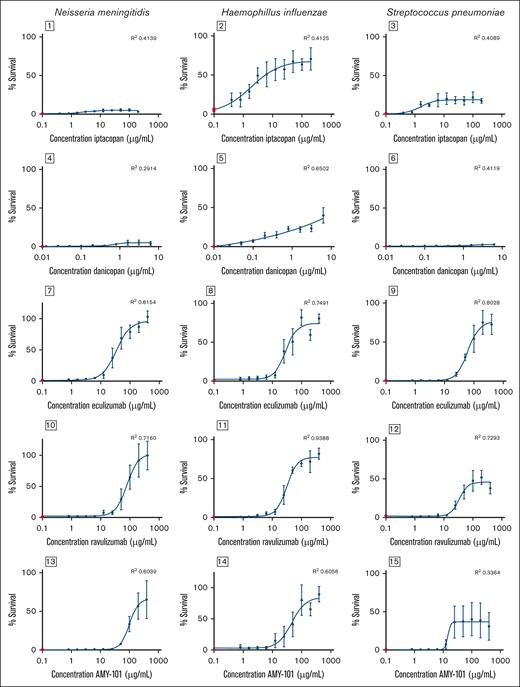

Effect of iptacopan (antifactor B), danicopan (antifactor D), eculizumab (anti-C5), ravulizumab (anti-C5), and AMY-101 (anti-C3) on complement-mediated killing (Nm and Hi) or whole blood killing (Sp). A twofold dilution series of complement inhibitors was made with pooled plasma. Gram-negative bacteria (Nm and Hi) were incubated in 10% plasma or heat-inactivated plasma for 30 minutes at 37°C, and survival was calculated by determining colony-forming units. For S pneumoniae, bacteria were added to washed blood cells and mixed with undiluted plasma or with undiluted heat-inactivated plasma and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C while shaking, and survival was calculated by determining colony-forming units. The percentage survival was normalized to heat-inactivated pooled plasma without inhibitors. Survival in pooled human plasma (mean ± standard error of the mean) is illustrated in red in each graph. The concentration effect curve on bacterial survival is presented in black (mean ± standard error of the mean is shown; Nm: n = 5 for AMY-101 and eculizumab, n = 4 for iptacopan, danicopan, and ravulizumab; Hi: n = 3 for ravulizumab, n = 5 for AMY-101, danicopan, and eculizumab, n = 6 for iptacopan; Sp: n = 4 for all inhibitors). IC50 values were determined using variable-slope, 4-parameter nonlinear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism.

Effect of iptacopan (antifactor B), danicopan (antifactor D), eculizumab (anti-C5), ravulizumab (anti-C5), and AMY-101 (anti-C3) on complement-mediated killing (Nm and Hi) or whole blood killing (Sp). A twofold dilution series of complement inhibitors was made with pooled plasma. Gram-negative bacteria (Nm and Hi) were incubated in 10% plasma or heat-inactivated plasma for 30 minutes at 37°C, and survival was calculated by determining colony-forming units. For S pneumoniae, bacteria were added to washed blood cells and mixed with undiluted plasma or with undiluted heat-inactivated plasma and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C while shaking, and survival was calculated by determining colony-forming units. The percentage survival was normalized to heat-inactivated pooled plasma without inhibitors. Survival in pooled human plasma (mean ± standard error of the mean) is illustrated in red in each graph. The concentration effect curve on bacterial survival is presented in black (mean ± standard error of the mean is shown; Nm: n = 5 for AMY-101 and eculizumab, n = 4 for iptacopan, danicopan, and ravulizumab; Hi: n = 3 for ravulizumab, n = 5 for AMY-101, danicopan, and eculizumab, n = 6 for iptacopan; Sp: n = 4 for all inhibitors). IC50 values were determined using variable-slope, 4-parameter nonlinear regression analysis in GraphPad Prism.

AMY-101 inhibited the binding of C3 and C5b-9 to the surface of Nm, Hi, and Sp in a dose-depended manner with an IC50 of 6.8 μg/mL, 17.4 μg/mL, and 10.4 μg/mL, respectively, but the deposition of C5b-9 was not completely blocked on the surface of Nm and Hi (Figure 1).

Finally, we determined the effect of complement inhibition on killing of Nm, Hi, and Sp. The effect of iptacopan on bacterial killing was limited for Nm (maximal survival <5%), moderate for Sp (maximal survival ∼20%), and more pronounced for Hi (maximal survival ∼70%) (Figure 2). The effect of danicopan on bacterial killing was also limited for Nm and Sp (maximal survival percentage <5%) and moderate for Hi (maximal survival ∼40%). Plasma containing eculizumab, ravulizumab, or AMY-101 had a dose-dependent inhibition of killing of Nm (IC50 34.2, 79.2, and 100.9 μg/mL, respectively), Hi (IC50 28.5, 31.4, and 46.6 μg/mL, respectively), and Sp (IC50 62.4, 34.2, and 14.7 μg/mL, respectively). Increased survival of Nm with eculizumab and ravulizumab was more pronounced, close to 100%, compared with AMY-101, at ∼70% (Figure 2).

In this study, we confirmed that AP inhibitors have a more limited effect on complement deposition and killing of both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria compared with C3 and C5 inhibitors. Previous studies demonstrated a significant inhibitory effect of AP inhibitors on serum bactericidal activity of prevaccination serum, but vaccination largely mitigated this effect for all pathogens.28-30 In our study, we used pooled human plasma from donors and did not measure pathogen-specific antibody levels in the blood samples; however, several donors had been vaccinated against selected pathogens. On the basis of the in vitro results of our study and previous studies, the infection risk of AP inhibitors might thus be lower than for C5 and C3 inhibitors, especially when patients are adequately vaccinated against selected pathogens. Case series of patients with a factor B- or D-deficiency reveal increased susceptibility for infections with Nm and Sp,31-34 but these data cannot be extrapolated to AP inhibitors. The results of long-term safety studies are necessary to determine the exact risk of AP inhibitors in clinical practice.

For C5 inhibitors, previous studies revealed that killing of Nm serogroup B in whole blood was impaired in the presence of a C5 inhibitor, both prevaccination and postvaccination with 4CMenB.14,15,19,28 These results are consistent with clinical practice, as eculizumab therapy is associated with a >1000-fold increased incidence of meningococcal disease despite vaccination.35 For Hi, comparable results with our study were reported in literature.30 In clinical practice, increased susceptibility to Hi has not been observed in patients with C5 deficiency30 and patients treated with C5 inhibitors,36 indicating that killing of Hi does not completely rely on the formation of the membrane attack complex. For Sp, it was found that C5 inhibition only marginally impaired bacterial killing of Sp,29 which could be explained by differences in anti-C5 antibody (tesidolumab), a slightly lower concentration of anti-C5 antibody (50 μg/mL) and potentially differences in anti-Sp antibody levels between studies. In clinical practice, infections with Sp are not more often found in patients treated with C5 inhibitors compared with the general population.36

For C3 inhibitor AMY-101, our results are largely in line with previous studies investigating the effect of C3 inhibition on bacterial killing of Nm, Hi, and Sp.28-30 Of note, AMY-101 is a monovalent compstatin analog, whereas pegcetacoplan is bivalent, resulting in differences in binding to surface-bound C3b.37 For C3 inhibitors, the general concern was that susceptibility to infections would increase due to the central role of C3 in complement activation, amplification, and effector function.38 C3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan has a better-than-expected safety profile with an infection risk comparable with C5 inhibitors, but further research regarding the infection risk is still ongoing.38 There are several possible explanations for the better-than-expected safety profile. First, even a small amount of C3 in the circulation (<10%) can reduce infection risk.39 Second, C5b-9 deposition on the bacterial surface of Nm and Hi was not completely inhibited, enabling killing of gram-negative pathogens by the membrane attack complex. Third, C3 also plays a major role in early stages of development of the immune system, which is affected in patients with a C3 deficiency but not in patients using C3 inhibitors.40 The results from the long-term efficacy and safety studies of pegcetacoplan and novel C3 inhibitors are necessary to determine the exact risk of these drugs in clinical practice.41

Our study has several limitations. Owing to the current study design, we were unable to use plasma of patients treated with complement inhibitors, which might better reflect the actual clinical setting. In addition, lectin pathway inhibitors, such as narsoplimab, are being investigated for several diseases42; however, we did not assess their effects on complement activation, complement deposition, and bacterial killing in this study.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that AP inhibitors have a limited effect on complement deposition and the killing of both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria compared with C3 and C5 inhibitors.

Contribution: Z.d.B. and J.D.L. performed the experiments; M.t.A., Z.d.B., and J.D.L. analyzed the results and made the figures; M.t.A., S.M.C.L., N.C.A.J.v.d.K., R.t.H., M.I.d.J., and J.D.L. designed the research; M.t.A. and J.D.L. wrote the manuscript; each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision; and all authors approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.C.A.J.v.d.K. is a member of the European Reference Network for Rare Kidney Diseases (project number 739532); received consultancy fees from Roche Pharmaceuticals, Alexion, and Novartis; and is a subinvestigator in APL2-C3G trial, Apellis. R.t.H. has received research funding from Amgen. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeroen D. Langereis, Section of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Laboratory of Medical Immunology, Radboud University Medical Center, P.O. Box 9101, 6500 HB Nijmegen, The Netherlands; email: jeroen.langereis@radboudumc.nl.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Jeroen D. Langereis (jeroen.langereis@radboudumc.nl).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.