In this issue of Blood Advances, Soumerai et al1 present consensus guidelines for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma. This article, to our knowledge, represents the first report from the expert panel convened by the Lymphoma Research Foundation (LRF).

Although the phrase “paradigm shift” is often used in oncology, its use is truly justified when describing the transformation of the CLL treatment landscape after the introduction of targeted agents. In the past decade, we have witnessed the evolution of a new era in CLL treatment, marked by single-arm studies followed by randomized trials that consistently demonstrated the superior efficacy of targeted drugs, either as monotherapy or in combination, compared with the conventional chemoimmunotherapy once considered the standard of care.2 As a result, the CLL field has gained regulatory approval for numerous novel targeted treatments, each revealed to be “better” than chemotherapy.

The CLL community deserves to be recognized for the design and execution of numerous head-to-head trials comparing novel regimens. However, we must wait for the results of these studies in the coming years. In the meantime, we have a range of effective treatments with varying schedules (indefinite vs time limited) and safety profiles. In conversation with patients, in-depth discussions are essential to highlight the differences, pros, and cons of each approach. These shared decisions are made by considering disease-related factors (molecular and cytogenetic markers), treatment-related factors (duration, adverse event profiles), and patient-related factors (age, comorbidities, social support, and patient preferences). Consensus guidelines are valuable in highlighting the discussion points to facilitate these nuanced conversations by incorporating updated data from long-term follow-up of the trials and the cumulative safety information.3

The expert panel should be commended for providing specific and practical recommendations, some of which may not be apparent in other practice guidelines. As is inherent to any consensus guidelines, the panel was understandably cautious to remain inclusive, unbiased, and evidence based. At the same time, they have done an exceptional work in sharing their expert opinions in areas where published data are either lacking or unclear.

The CLL community eagerly anticipates the results of several potentially practice-changing or practice-informing trials. For asymptomatic patients, the SWOG S1925 (NCT04269902) study will determine whether early intervention with time-limited venetoclax and obinutuzumab improves survival in patients with high-risk CLL. The CLL17 study (NCT04608318), conducted by the German CLL Study Group, is expected to have a significant impact, comparing outcomes among patients treated with ibrutinib (indefinite), venetoclax and obinutuzumab (time limited), and ibrutinib and venetoclax (time limited). The MAJIC trial (NCT05057494) evaluates an all-oral, time-limited therapy using a second-generation Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, acalabrutinib, in combination with venetoclax vs the current standard of care, venetoclax and obinutuzumab. Similarly, the CELESTIAL TNCLL study (NCT06073821) evaluates another novel, all-oral combination of zanubrutinib and sonrotoclax vs venetoclax and obinutuzumab in a time-limited fashion. The important question of covalent vs noncovalent BTK inhibitors will be partially addressed by the BRUIN-CLL-314 (NCT05254743) study comparing pirtobrutinib with ibrutinib and the BELLWAVE-011 (NCT06136559) trial testing nemtabrutinib against the BTK inhibitor of choice. In previously treated patients, the BRUIN-CLL-322 (NCT04965493) trial will explore the potential added benefit of pirtobrutinib in combination with venetoclax and rituximab and the BELLWAVE-010 (NCT05947851) tests the venetoclax and nemtabrutinib combination vs venetoclax and rituximab. In addition, several studies are investigating drugs with novel mechanisms of action in the relapsed setting. Examples include BTK degraders, T-cell engagers, novel cellular immunotherapies, and new targeted agents. Beyond the mentioned examples, a growing number of studies, both industry-sponsored and investigator-initiated, explore different combination and sequencing strategies for treatment of CLL and may make it to the next versions of the guidelines. Future iterations of these guidelines may illuminate and guide the use of measurable residual disease testing in clinical practice. Furthermore, the integration of information about resistance mutations that may arise in patients treated with BTK inhibitors or B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitors is likely to shape future management strategies and could potentially make it to future practice guidelines.

Although these guidelines serve as an important resource for clinical practice, they are developed under the assumption of full access to all available and approved drugs and diagnostics. Unfortunately, availability, accessibility, and affordability are only true in a small number of countries, as access to nonchemotherapy CLL therapies remains very limited globally. Even when available, patients in many areas of the world may only have access to a limited selection of options, and the high cost of these drugs remains prohibitive.4 Systematic research is needed to better understand the details of practice in the global context, where deviation from approved treatment schedules and dosing may occur due to cost and access issues. Unfortunately, the global low-resource setting is not always a priority for industry partners. Most guidelines identify and optimize treatment strategies based on the reality of the resource-affluent countries, which means that the practice guidelines at the global level will most likely not be based on prospective trials.

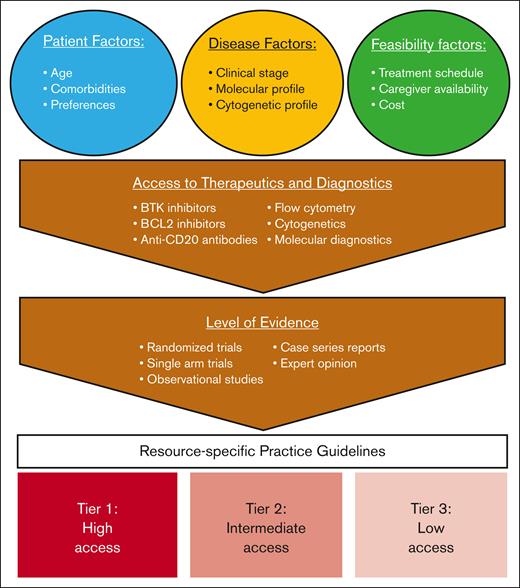

Altogether, there is an unmet need for developing CLL practice guidelines tailored to the available local resources and designed to accommodate different tiers of access. Such guidelines must consider both diagnostic limitations and availability of therapeutic agents. For example, recommendations for a setting where only ibrutinib is accessible must differ from those for a setting with broader access to diagnostics and CLL therapeutics (see figure).5,6

Development of resource-specific guidelines for CLL. BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2.

Development of resource-specific guidelines for CLL. BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2.

There are several platforms that can support the CLL expert community for such an effort. This presents a great opportunity for collaboration between leading research and professional foundations such as the American Society of Hematology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, or LRF to work with the International Workshop for CLL through its global partnership subcommittee. This helps the formation of a diverse and inclusive expert panel with representatives from areas with different levels of access.

In conclusion, we congratulate our colleagues on the panel for producing this thoughtful, detailed, and balanced guide for treating CLL. Pain is global, but access to pain relief is highly localized and inequitable. We sincerely hope that these recommendations are updated, balancing access and excess, regularly given the rapidly evolving landscape of CLL treatment. As we collectively strive for universal access to novel diagnostic and therapeutic resources globally, we call on the CLL expert community and professional organizations to take action in developing practice guidelines that are customized and resource specific. This effort is essential to ensure that all patients living with a diagnosis of CLL receive the best possible care to overcome geographic health disparities.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.S. has received consulting fees from, and served on advisory boards, steering committees, or data safety monitoring committees of AbbVie, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Genmab, Janssen, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Kite Pharma, Eli Lilly, Fate Therapeutics, Nurix, and Merck; and has received research funding from Mustang Bio, Genentech, AbbVie, BeiGene, AstraZeneca, Genmab, MorphoSys/Incyte, Vincerx, and BMS (spouse). B.F. has received research funding from Angiocrine, AbbVie, BMS/Juno, BeiGene, Genmab, Genentech, and Loxo Oncology; and has served on advisory boards of, received consulting fees from, or received honoraria from AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, Adaptive Biotechnologies, AstraZeneca, BMS, BeiGene, Eli/Lilly, Genentech, Genmab, and Pharmacyclics. N.J. has received research funding from Pharmacyclics, AbbVie, Genentech, AstraZeneca, BMS, Pfizer, ADC Therapeutics, Cellectis, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Precision Biosciences, Fate Therapeutics, Kite/Gilead, MingSight, Takeda, Medisix, Loxo Oncology, NovalGen, Dialectic Therapeutics, Newave, Novartis, Carna Biosciences, Sana Biotechnology, and KisoJi Biotechnology; and has served on advisory boards of, or received honoraria from Pharmacyclics, Janssen, AbbVie, Genentech, AstraZeneca, BMS, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Kite/Gilead, Precision Biosciences, BeiGene, Cellectis, MEI Pharma, Ipsen, CareDx, MingSight, Autolus, and NovalGen.