Key Points

We developed of a high-throughput screening assay to identify small-molecule inhibitors of fibrin-mediated clot retraction.

Screening 9710 compounds from DRLs led to the identification of 162 inhibitors with a variety of targets.

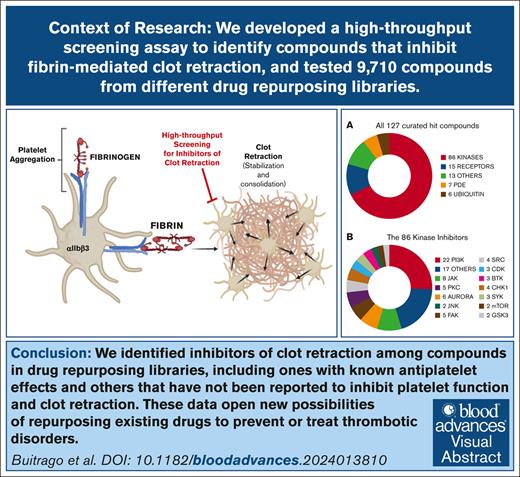

Visual Abstract

Platelet clot retraction, the ultimate phase of platelet thrombus formation, is critical for clot stabilization. It requires functional αIIbβ3 receptors, fibrin, and the integrated actions of the actin-myosin contractile and cytoskeletal systems. Disturbances in clot retraction have been associated with both bleeding and thrombosis. We recently demonstrated that platelets treated with the αIIbβ3 antagonist peptide Arg-Gly-Asp-Trp, which eliminates fibrinogen-mediated platelet aggregation, are still able to retract clots. We have exploited this observation to develop an unbiased, functional high-throughput assay to identify small-molecule inhibitors of fibrin-mediated clot retraction adapted for a 384-well plate format. We tested 9710 compounds from drug-repurposing libraries (DRLs). These libraries contain compounds that are either US Food and Drug Administration approved or have undergone preclinical/clinical development. We identified 27 compounds from the Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds library as inhibitors of clot retraction, of which 14 are known inhibitors of platelet function. From the DRLs, we identified 135 compounds (1.6% hit rate). After extensive curation, these compounds were categorized based on the activity of their reported target. Multiple kinase and phosphodiesterase inhibitors with known antiplatelet effects were identified, along with multiple deubiquitination and receptor inhibitors, as well as compounds that have not previously been reported to have antiplatelet activity. Studies of 1 of the deubiquitination inhibitors (degrasyn) suggest that its effects are downstream of thrombin-induced platelet-fibrinogen interactions and thus may permit the separation of platelet thrombin-induced aggregation-mediated events from clot retraction. Additional studies of the identified compounds may lead to novel mechanisms of inhibiting thrombosis.

Introduction

Clot retraction (CR) is the ultimate phase of thrombus formation, coming after platelet deposition, platelet aggregation, thrombin generation, and fibrin formation. It results in a clot that is more stable and more resistant to thrombolysis. As a result, it contributes to the irreversibility of the process, which may be very valuable in achieving hemostasis or very dangerous in consolidating thrombi that compromise vascular patency and lead to myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral vascular disease, or microangiopathy.1 CR requires fibrin, functional platelet integrin αIIbβ3 receptors (because patients with Glanzmann thrombasthenia, who lack these receptors on a genetic basis, have diminished or absent CR),2-4 and the integrated actions of the platelet actin-myosin contractile and cytoskeletal systems. Evidence for CR occurring in vivo comes from vascular injury models in animals5 and from finding polyhedral erythrocytes, which are formed under the pressure of fibrin retraction,6,7 in thrombi from patients with myocardial infarction,8,9 stroke,10 and venous thromboembolism.11 CR decreases the fluid content of the clot by >90% in vitro, increases its stiffness and stability, and reduces its ability to be lysed by the fibrinolytic system.12-14 However, partial fibrinolysis actually facilitates CR because of its impact on the viscoelastic properties of the clot,5 and CR differentially modulates fibrinolysis, enhancing the rate of internal fibrinolysis, while more dramatically slowing the rate of external fibrinolysis.15 Thus, CR is presumed to play an important role in securing hemostasis. Paradoxically, decreased CR may contribute to thrombosis by producing clots that are more obstructive, as in stroke.16 In addition, decreased CR has been linked to venous thromboembolic disease.15,17

The CR process is still poorly understood, especially with regard biochemical events that may be specific to the process. Platelet outside-in signaling pathways have been extensively studied,18 but which, if any, signal transduction pathways differentiate platelet aggregation from CR remains unknown. The interaction of fibrinogen with platelets differs between platelet aggregation and CR,19,20 and thus these processes may use different signaling machinery.21

We recently studied the interaction of platelets with fibrin in the absence of the confounding effects of fibrinogen-mediated platelet aggregation by adding the peptide Arg-Gly-Asp-Trp (RGDW), which inhibits the initial platelet aggregation response mediated by fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 but leaves intact a delayed wave (DW) of platelet pseudoaggregation as αIIbβ3 receptors interact with the fibrin.20 Both the DW and CR can be inhibited by the αIIbβ3 antagonists eptifibatide and monoclonal antibody 7E3 but only at much higher concentrations than needed to inhibit platelet aggregation. Similarly, although RGDW, monoclonal antibody 10E5, and abciximab are all potent inhibitors of platelet aggregation, they do not inhibit the DW or CR,20 suggesting that fibrin differs from fibrinogen in its avidity and/or mechanism of binding.

Small-molecule inhibitors of CR may help dissect different aspects of fibrin-mediated CR and if they inhibit CR and thrombus consolidation without inhibiting fibrinogen-mediated platelet aggregation, they may have better safety profiles as therapeutics. We therefore developed a robust high-throughput screening (HTS) assay and performed an unbiased phenotypic screen, that is, a screen that did not prioritize compounds based on a hypothesis regarding their mechanism of action or pathway involved, to identify compounds that inhibit CR, focusing on those that might selectively inhibit CR while leaving intact fibrinogen-mediated platelet aggregation. We realized, however, that our screen would likely also identify compounds that affect pathways used by both platelet aggregation and CR and, thus, we did not expect that our screen would be absolutely specific for inhibitors of CR, independent of platelet aggregation. We tested 9710 compounds in drug-repurposing libraries (DRLs) in the Rockefeller University collection.22 All of these compounds have obtained US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, undergone clinical development, or undergone preclinical characterization. The libraries contain drugs that are known to have antiplatelet effects, which served as valuable positive controls. Here, we describe the assay, and the compounds identified in the screen.

Methods

Miniaturized CR assay for HTS

Washed platelets were prepared from platelet concentrates, treated with RGDW (150 μM), and supplemented with 100 μg/mL of fibrinogen as detailed in supplemental Materials. The final concentration of all test compounds was 10 μM, which was dictated by the stock concentrations of the compounds in the libraries, the limit on the volume of test compounds that could be committed to our screen, and the requisite volumes of the other components of the assay. We also judged 10 μM to be a reasonable cutoff for the minimum potency of a compound to justify further exploration.

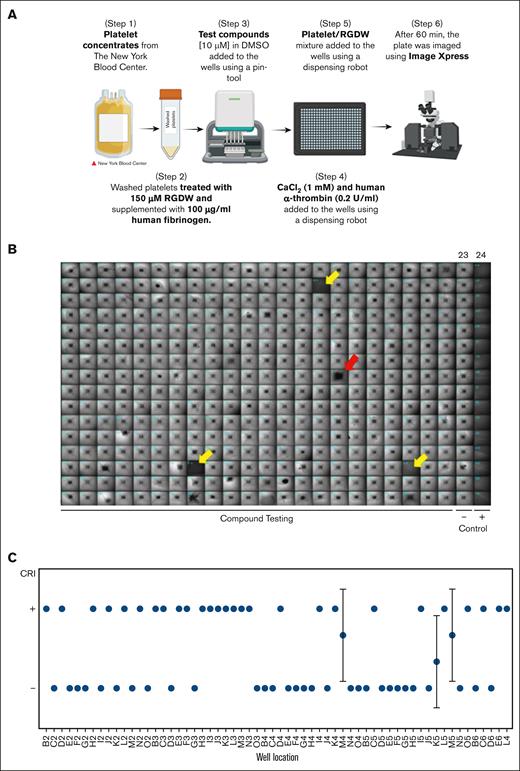

We miniaturized the CR assay so that it could be performed in 384-well microtiter plates with a final volume of 50 μL using the following steps (Figure 1A): (1) 10 μL of HEPES modified Tyrode buffer was added to black-walled, clear-bottomed, untreated polystyrene, nonsterile 384-well microtiter plate wells (Corning) by a Multidrop Combi-dispense robot (Thermo Fisher); (2) 200 nL of the test compound (final concentration, 10 μM) in dimethyl sulfoxide was dispensed with a Janus-384-MDT NanoHead (PerkinElmer), yielding a final dimethyl sulfoxide concentration of 0.4%, which preliminary studies demonstrated did not interfere with the CR assay; (3) 4 μL of a solution of CaCl2 (1 mM final concentration) and human α-thrombin (0.2 U/mL final concentration) were added to the wells by the robot, followed by a centrifugation step of 1 minute at 180g to collect all the liquid at the bottom of the wells; (4) 36 μL of the platelet/RGDW mixture was added to the wells by the robot, yielding a final platelet count of 2.5 × 105/μL; (5) plates were incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes; and (6) plates were imaged using the Image-Xpress high-content imaging system (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Negative controls consisted of wells in column 23 containing platelets without any compound. Positive controls were wells in column 24 containing platelets not stimulated by the CaCl2/α-thrombin solution.

The HTS assay. (A) Stepwise diagram of the miniaturized CR assay for HTS. (B) Prototypical 384-well plate resulting from the miniaturized CR assay. Retracted clots in the negative control column (23), which were treated with thrombin (0.2 U/mL) but no test compounds, appear as small, dense squares, whereas the wells in the positive control column (24), which did not receive thrombin, appear uniformly dark. The vast majority of the compounds tested in the plate do not inhibit CR, but there are 3 wells that show full inhibition of CR and were considered a hit (yellow arrows) and 1 that shows incomplete inhibition (red arrow), that is, not considered a hit. (C) Results of testing 60 compounds on 3 different dates using 3 different platelet preparations. The results were averaged and displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). CRI, CR inhibition; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. Figure panel A created with BioRender.com.

The HTS assay. (A) Stepwise diagram of the miniaturized CR assay for HTS. (B) Prototypical 384-well plate resulting from the miniaturized CR assay. Retracted clots in the negative control column (23), which were treated with thrombin (0.2 U/mL) but no test compounds, appear as small, dense squares, whereas the wells in the positive control column (24), which did not receive thrombin, appear uniformly dark. The vast majority of the compounds tested in the plate do not inhibit CR, but there are 3 wells that show full inhibition of CR and were considered a hit (yellow arrows) and 1 that shows incomplete inhibition (red arrow), that is, not considered a hit. (C) Results of testing 60 compounds on 3 different dates using 3 different platelet preparations. The results were averaged and displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). CRI, CR inhibition; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. Figure panel A created with BioRender.com.

Image analysis

The 384-well plates were analyzed with a 4× bright-field objective lens on the ImageXpress XLS wide-field Micro reader (Molecular Devices) with MetaXpress software version 4.1 (Molecular Devices). An image application from MetaXpress software 6.67 was used to analyze the images by identifying objects (retracted clots) in the field (supplemental Figure 1). The wells exhibiting CR inhibition were easily distinguished from those without CR by simple visual inspection. Thus, we complemented the automated image analysis by visual inspection of each plate, with results annotated in a binary format. See supplemental Materials for a detailed description.

Libraries

A total of 9710 compounds were screened from libraries obtained from several vendors as indicated in supplemental Materials.

Results

Development and validation of the high-throughput screen to identify inhibitors of CR

Figure 1B shows a typical test plate in which CR in the wells in the negative control, lane 23, are easily identified by the small, dark square in the center of the well, with a surrounding lighter halo. In contrast, the absence of CR in the wells in the positive control, lane 24, is easily discernable by their uniformly dark appearance. We therefore fit the automated readout to a binary result: wells containing compounds that scored a value of 1 were judged to show CR inhibition and so were designated as positive (+) for CR inhibition (defined as 100% opacity of the well area) and those with a score of 0 were designated as negative (−) for CR inhibition (any degree of retraction). For example, the 3 wells identified by the yellow arrows (Figure 1B) would be graded 1 (no CR) and the sample in well 16H (red arrow) would be rated as a negative result.

We tested 1280 compounds from the Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds (LOPAC) DRL as a pilot and 8430 compounds from other DRLs. DRLs contain compounds that are either FDA approved or have undergone preclinical/clinical development. The LOPAC DRL contains pharmacologically active compounds that cover major target classes such as G protein receptors, kinases, gene regulators, and neurotransmitters. The vendors who supplied the DRLs are detailed in supplemental Materials.

The pilot study resulted in the identification 27 hit compounds (2.1%) that are listed in Table 1. It was reassuring that 14 of 24 compounds that were “hits” have been reported to inhibit platelet function (marked with an asterisk in the table). The pilot study results showed that the assay is amenable to HTS and sensitive to known inhibitors of platelet function.

Hit compounds identified in primary screen in LOPAC

| . | Identifier . | Name . | Reported main target . | SMILES . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOPAC library | RU-0084045 | Bay 11-7085∗ | IκBα phosphorylation | S(C1=CC=C(C(C)(C)C)C=C1)(/C=C/C#N)(=O)=O | 23 |

| RU-0084482 | 273921-90-7 | Nitric oxide donor | [C@H](C(SN=O)(C)C)(C(=O)O)NC(=O)C | ||

| RU-0084568 | Bay 11-7082∗ | NF-κB | C1(C)=CC=C(S(=O)(/C=C/C#N)=O)C=C1 | 24 | |

| RU-0084103 | Cilostamide∗ | PDE | N1C(=O)C=CC2=CC(OCCCC(N(C3CCCCC3)C)=O)=CC=C12 | 25,26 | |

| RU-0000724 | Cilostazole∗ | PDE | N1(C2CCCCC2)N=NN=C1CCCCOC1=CC2=C(NC(=O)CC2)C=C1 | 27,28 | |

| RU-0084329 | Cortisol succinate | C[C@]12C[C@H](O)[C@H]3[C@@H](CCC4=CC(=O)CC[C@]34C)[C@@H]1CC[C@]2(O)C(=O)COC(=O)CCC(=O)O | |||

| RU-0084205 | DCEBIO | Potassium channels | C1(=O)N(CC)C2=CC(Cl)=C(Cl)C=C2N1 | ||

| RU-0084187 | Enoximone | PDE | C1(C(C2=CC=C(SC)C=C2)=O)=C(C)NC(=O)N1 | ||

| RU-0084245 | Forskolin∗ | Adenylyl cyclase | C12(O)C(C)(C(OC(=O)C)C(O)C3C1(C)C(O)CCC3(C)C)OC(C=C)(C)CC2=O | 29-31 | |

| RU-0001059 | IBMX∗ | PDE | CC(C)CN1C2=C(N=CN2)C(=O)N(C)C1=O | 32,33 | |

| RU-0084345 | Imazodan | PDE | N1=C(C2=CC=C(N3C=NC=C3)C=C2)CCC(=O)N1 | ||

| RU-0084713 | Lificiguat (YC-1)∗ | Soluble guanylyl cyclase | N1=C(C2=CC=C(CO)O2)C2=CC=CC=C2N1CC1=CC=CC=C1 | 34 | |

| RU-0084077 | Lopac0_000237 | C[N+](C)(C)COP(O)(=O)OP(O)(=O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](N2C=CC(N)=NC2=O)[C@H](O)[C@@H]1O | |||

| RU-0084402 | Lopac-M-2922 | N12C(=NN=C1C)C=C(C1=CC=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C1)C=N2 | |||

| RU-0083889 | Milrinone∗ | PDE | C1(C#N)=CC(C2=CC=NC=C2)=C(C)NC1=O | 35,36 | |

| RU-0000199 | Nifedipine∗ | Calcium channel blocker | C1(C2=CC=CC=C2[N+](=O)[O-])C(C(OC)=O)=C(C)NC(C)=C1C(OC)=O | 37 | |

| RU-0084335 | NSC95397 | Cdc25 | C1(SCCO)=C(SCCO)C(=O)C2=CC=CC=C2C1=O | ||

| RU-0084741 | Olprinone∗ | PDE | CC1=C(C2=CN3C=CN=C3C=C2)C=C(C#N)C(=O)N1 | 38 | |

| RU-0000311 | Papaverine∗ | PDE | COC1=CC=C(CC2=C3C=C(OC)C(OC)=CC3=CC=N2)C=C1OC | 39 | |

| RU-0084547 | Quazinone (Ro 13-6438) | PDE | C12=NC(=O)[C@@H](C)N1CC1=C(N2)C=CC=C1Cl | ||

| RU-0084589 | SB-236057∗ | 5-HT4 receptor | CCCCN1CCC(COC(=O)C2=CC(Cl)=C(N)C3=C2OCCO3)CC1 | 40 | |

| RU-0092507 | SCHEMBL971886 | O=N[Fe](C#N)(C#N)(C#N)(C#N)C#N | |||

| RU-0084528 | SU9516 | CDK2 | C1(=C∖C2=CN=CN2)∖C(=O)NC2=CC=C(OC)C=C12 | ||

| RU-0084737 | Thapsigardin∗ | SERCA | [C@@]12(O)[C@H](C3=C(C)[C@H](OC(/C(=C∖C)C)=O)[C@@H](OC(=O)CCCCCCC)[C@]3([H])[C@](OC(=O)C)(C)C[C@@H]1OC(=O)CCC)OC(=O)[C@]2(O)C | 41 | |

| RU-0084665 | Trequinsin∗ | PDE | COC1=CC2=C(C=C1OC)C1=C/C(=N∖C3=C(C)C=C(C)C=C3C)N(C)C(=O)N1CC2 | 42 | |

| RU-0084105 | ZPCK | Protease inhibitor | C(N[C@H](C(=O)CCl)CC1=CC=CC=C1)(=O)OCC1=CC=CC=C1 |

| . | Identifier . | Name . | Reported main target . | SMILES . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOPAC library | RU-0084045 | Bay 11-7085∗ | IκBα phosphorylation | S(C1=CC=C(C(C)(C)C)C=C1)(/C=C/C#N)(=O)=O | 23 |

| RU-0084482 | 273921-90-7 | Nitric oxide donor | [C@H](C(SN=O)(C)C)(C(=O)O)NC(=O)C | ||

| RU-0084568 | Bay 11-7082∗ | NF-κB | C1(C)=CC=C(S(=O)(/C=C/C#N)=O)C=C1 | 24 | |

| RU-0084103 | Cilostamide∗ | PDE | N1C(=O)C=CC2=CC(OCCCC(N(C3CCCCC3)C)=O)=CC=C12 | 25,26 | |

| RU-0000724 | Cilostazole∗ | PDE | N1(C2CCCCC2)N=NN=C1CCCCOC1=CC2=C(NC(=O)CC2)C=C1 | 27,28 | |

| RU-0084329 | Cortisol succinate | C[C@]12C[C@H](O)[C@H]3[C@@H](CCC4=CC(=O)CC[C@]34C)[C@@H]1CC[C@]2(O)C(=O)COC(=O)CCC(=O)O | |||

| RU-0084205 | DCEBIO | Potassium channels | C1(=O)N(CC)C2=CC(Cl)=C(Cl)C=C2N1 | ||

| RU-0084187 | Enoximone | PDE | C1(C(C2=CC=C(SC)C=C2)=O)=C(C)NC(=O)N1 | ||

| RU-0084245 | Forskolin∗ | Adenylyl cyclase | C12(O)C(C)(C(OC(=O)C)C(O)C3C1(C)C(O)CCC3(C)C)OC(C=C)(C)CC2=O | 29-31 | |

| RU-0001059 | IBMX∗ | PDE | CC(C)CN1C2=C(N=CN2)C(=O)N(C)C1=O | 32,33 | |

| RU-0084345 | Imazodan | PDE | N1=C(C2=CC=C(N3C=NC=C3)C=C2)CCC(=O)N1 | ||

| RU-0084713 | Lificiguat (YC-1)∗ | Soluble guanylyl cyclase | N1=C(C2=CC=C(CO)O2)C2=CC=CC=C2N1CC1=CC=CC=C1 | 34 | |

| RU-0084077 | Lopac0_000237 | C[N+](C)(C)COP(O)(=O)OP(O)(=O)OC[C@H]1O[C@@H](N2C=CC(N)=NC2=O)[C@H](O)[C@@H]1O | |||

| RU-0084402 | Lopac-M-2922 | N12C(=NN=C1C)C=C(C1=CC=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C1)C=N2 | |||

| RU-0083889 | Milrinone∗ | PDE | C1(C#N)=CC(C2=CC=NC=C2)=C(C)NC1=O | 35,36 | |

| RU-0000199 | Nifedipine∗ | Calcium channel blocker | C1(C2=CC=CC=C2[N+](=O)[O-])C(C(OC)=O)=C(C)NC(C)=C1C(OC)=O | 37 | |

| RU-0084335 | NSC95397 | Cdc25 | C1(SCCO)=C(SCCO)C(=O)C2=CC=CC=C2C1=O | ||

| RU-0084741 | Olprinone∗ | PDE | CC1=C(C2=CN3C=CN=C3C=C2)C=C(C#N)C(=O)N1 | 38 | |

| RU-0000311 | Papaverine∗ | PDE | COC1=CC=C(CC2=C3C=C(OC)C(OC)=CC3=CC=N2)C=C1OC | 39 | |

| RU-0084547 | Quazinone (Ro 13-6438) | PDE | C12=NC(=O)[C@@H](C)N1CC1=C(N2)C=CC=C1Cl | ||

| RU-0084589 | SB-236057∗ | 5-HT4 receptor | CCCCN1CCC(COC(=O)C2=CC(Cl)=C(N)C3=C2OCCO3)CC1 | 40 | |

| RU-0092507 | SCHEMBL971886 | O=N[Fe](C#N)(C#N)(C#N)(C#N)C#N | |||

| RU-0084528 | SU9516 | CDK2 | C1(=C∖C2=CN=CN2)∖C(=O)NC2=CC=C(OC)C=C12 | ||

| RU-0084737 | Thapsigardin∗ | SERCA | [C@@]12(O)[C@H](C3=C(C)[C@H](OC(/C(=C∖C)C)=O)[C@@H](OC(=O)CCCCCCC)[C@]3([H])[C@](OC(=O)C)(C)C[C@@H]1OC(=O)CCC)OC(=O)[C@]2(O)C | 41 | |

| RU-0084665 | Trequinsin∗ | PDE | COC1=CC2=C(C=C1OC)C1=C/C(=N∖C3=C(C)C=C(C)C=C3C)N(C)C(=O)N1CC2 | 42 | |

| RU-0084105 | ZPCK | Protease inhibitor | C(N[C@H](C(=O)CCl)CC1=CC=CC=C1)(=O)OCC1=CC=CC=C1 |

CDK2, cyclin-dependent kinase 2; 5-HT4, serotonin type 4 receptor; IBMX, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine; SERCA, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca²⁺-ATPase; ZPCK, Z-Phe-chloromethylketone.

Compound reported to inhibit platelet function.

To assess assay reproducibility, we retested 60 molecules from the LOPAC library, of which ∼50% were hits on initial testing, on 3 separate days using 3 different platelet concentrates; 56 of 59 compounds gave the same results on all 3 assays, whereas 3 compounds exhibited discrepancies across testing days (Figure 1C). As a result, we implemented a confirmation step involving 3 repeat assays on 3 different days, and only compounds that inhibited CR in all 3 assays were considered true hits.

Results with compounds from DRLs

The 8430 compounds sourced from different DRLs exhibited a hit rate of 1.6%. We curated the hit compounds using PubChem (National Center for Biotechnology Information) and the compounds’ SMILES (simplified molecular input line entry system) identifier, focusing on the bioactivity data and chemical properties of each compound.

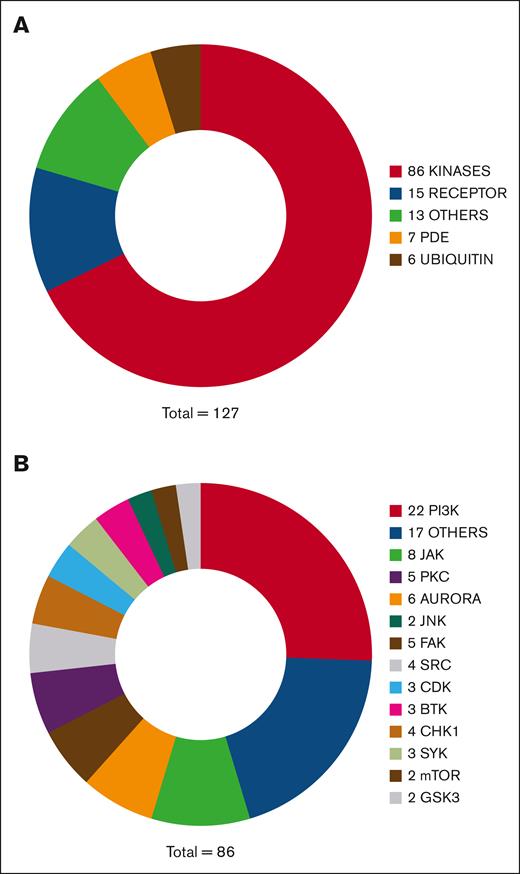

Figure 2A summarizes the broad functional categories identified for the DRL hit compounds and Tables 1 and 2 contain a comprehensive list of the 127 of 135 hit compounds listed in PubChem, with their reported main target and SMILES identifiers. Remarkably, 86 of these compounds are reported as kinase inhibitors. Figure 2B categorizes them according to their reported main target but kinase inhibitors commonly target multiple enzymes. A total of 15 hit compounds are reported to target a cell receptor, including αIIbβ3 itself (tirofiban). Tirofiban is a very high affinity antagonist of αIIbβ3 and thus is able to overcome the higher avidity of fibrin for αIIbβ3 compared with fluid-phase fibrinogen20 and inhibit CR. Other targeted receptors include the fibroblast growth factor receptor, the epidermal growth factor receptor, the FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3, the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2 serotonin receptor,40 and the δ-opioid receptor.43 Seven hit compounds are phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors; 6 hit compounds target molecules involved in the ubiquitination pathway, inhibiting E2 ligases or deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). Overall, 13 compounds were categorized as “other” because their reported target did not fall into 1 of the broad categories included in Figure 2A. They affect proteins involved in a variety of processes, including coagulation factor Xa, transcription factors (STAT3 and NF-κβ), apoptosis, cell proliferation and differentiation (ErbB3-binding protein 1), proteases, and of Cdc25 and phosphatase and tensin homolog phosphatases. Of note, the antiplatelet agents ticagrelor, clopidogrel, and ticlopidine, and aspirin and voraxapar were included in the DRL but none was identified as a hit compound.

Functional categories of hit compounds from DRLs based on reported their main target. (A) Pie chart of the classes of hit compounds based on the category of their main molecular target reported in PubChem. (B) Subdivision of the “kinase” category based on the reported main target of the hit compound.

Functional categories of hit compounds from DRLs based on reported their main target. (A) Pie chart of the classes of hit compounds based on the category of their main molecular target reported in PubChem. (B) Subdivision of the “kinase” category based on the reported main target of the hit compound.

Hit compounds identified in primary screen in DRLs

| Category . | Identifier . | Name . | Reported main target . | SMILES . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinases | RU-0422783 | Repotrectinib | ALK/ROS1/NTRK/Src/FAK | C[C@H]1CNC(=O)C2=C3N=C(N[C@H](C)C4=C(O1)C=CC(F)=C4)C=CN3N=C2 |

| RU-0423016 | Belizatinib (TSR-011) | ALK/TRK | CC(C)NC(=O)[C@H]1CC[C@@H](N2C3=CC(CN4CCC(C(C)(C)O)CC4)=CC=C3N/C2=N∖C(=O)C2=CC=C(F)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0422947 | Selonsertib | ASK1 | CC(C)N1C=NN=C1C1=CC=CC(NC(=O)C2=CC(N3C=NC(C4CC4)=C3)=C(C)C=C2F)=N1 | |

| RU-0279700 | TAK-901 | Aurora | C1N(C)CCC(NC(C2=C(C)C3=C(C(C4=CC(S(CC)(=O)=O)=CC=C4)=C2)C2=C(N3)N=CC(C)=C2)=O)C1 | |

| RU-0279648 | PF 03814735 | Aurora | C12=C(C=C(NC3=NC(NC4CCC4)=C(C(F)(F)F)C=N3)C=C1)[C@H]1CC[C@@H]2N1C(CNC(C)=O)=O | |

| RU-0279397 | CYC116 | Aurora | C1(NC2=CC=C(N3CCOCC3)C=C2)=NC=CC(C2=C(C)N=C(N)S2)=N1 | |

| RU-0279317 | Danusertib | Aurora | C1([C@H](C(N2CC3=C(C2)C(NC(=O)C2=CC=C(N4CCN(C)CC4)C=C2)=NN3)=O)OC)=CC=CC=C1 | |

| RU-0279484 | Hesperadin | Aurora | C1(NS(CC)(=O)=O)=CC=C2C(=C1)/C(=C(∖C1=CC=CC=C1)NC1=CC=C(CN3CCCCC3)C=C1)C(=O)N2 | |

| RU-0279329 | Alisertib | Aurora | C1=CC=C(F)C(C2=NCC3=C(C4=C2C=C(Cl)C=C4)N=C(NC2=CC(OC)=C(C(O)=O)C=C2)N=C3)=C1OC | |

| RU-0423010 | Acalabrutinib | BTK | CC#CC(=O)N1CCC[C@H]1C1=NC(C2=CC=C(C(=O)NC3=NC=CC=C3)C=C2)=C2N1C=CN=C2N | |

| RU-0423027 | RN486 | BTK | CN1CCN(C2=CN=C(NC3=CC(C4=CC=CC(N5C=CC6=CC(C7CC7)=CC(F)=C6C5=O)=C4CO)=CN(C)C3=O)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0422826 | ONO-4059 | BTK | NC1=C2N(C3=CC=C(OC4=CC=CC=C4)C=C3)C(=O)N(C3CCCN(C(=O)C=C)C3)C2=NC=N1 | |

| RU-0186817 | Amino purvalanol A | CDK | ClC1=CC(N)=CC(NC2=C3C(=NC(N[C@H](C(C)C)CO)=N2)N(C(C)C)C=N3)=C1 | |

| RU-0422987 | K03861 (AUZ454) | CDK | CN1CCN(CC2=CC=C(NC(=O)NC3=CC=C(OC4=NC(N)=NC=C4)C=C3)C=C2C(F)(F)F)CC1 | |

| RU-0186777 | (R)-DRF053 | CDK/CK1 | CC(C)N1C2=NC(N[C@H](CC)CO)=NC(NC3=CC(C4=NC=CC=C4)=CC=C3)=C2N=C1 | |

| RU-0279510 | AZD7762 | Chk1 | C1(F)=CC=CC(C2=CC(NC(N)=O)=C(C(N[C@@H]3CNCCC3)=O)S2)=C1 | |

| RU-0279783 | PF-477736 | Chk1 | C1=C(NC([C@@H](C2CCCCC2)N)=O)C=C2C3=C1C(=O)NN=CC3=C(C1=CN(C)N=C1)N2 | |

| RU-0186991 | PD 407824 | Chk1/Wee1 | O=C1NC(=O)C2=C3C(=CC(C4=CC=CC=C4)=C12)NC1=C3C=C(O)C=C1 | |

| RU-0423068 | PD0166285 | Chk1/Wee1 | CCN(CC)CCOC1=CC=C(NC2=NC3=C(C=N2)C=C(C2=C(Cl)C=CC=C2Cl)C(=O)N3C)C=C1 | |

| RU-0422703 | CC-115 | DNA-PK/TOR | CCN1C(=O)CNC2=NC=C(C3=C(C)N=C(C4=NNC=N4)C=C3)N=C12 | |

| RU-0279738 | TAE226 | FAK | C1(N2CCOCC2)=CC(OC)=C(NC2=NC(NC3=C(C(NC)=O)C=CC=C3)=C(Cl)C=N2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279636 | PF-562271 | FAK | C1=NC(N(C)S(=O)(C)=O)=C(CNC2=C(C(F)(F)F)C=NC(NC3=CC=C4C(=C3)CC(=O)N4)=N2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279535 | PF 573228 | FAK | N1C(=O)CCC2=C1C=CC(NC1=NC=C(C(F)(F)F)C(NCC3=CC=CC(S(=O)(=O)C)=C3)=N1)=C2 | |

| RU-0423060 | Defactinib | FAK/Pyk2 | CNC(=O)C1=CC=C(NC2=NC(NCC3=C(N(C)S(C)(=O)=O)N=CC=N3)=C(C(F)(F)F)C=N2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279636 | PF-562271 | FAK/Pyk2 | C1=NC(N(C)S(=O)(C)=O)=C(CNC2=C(C(F)(F)F)C=NC(NC3=CC=C4C(=C3)CC(=O)N4)=N2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279495 | TWS119 | GSK3 | C1=CC=C(OC2=NC=NC3=C2C=C(C2=CC=CC(N)=C2)N3)C=C1O | |

| RU-0422706 | TDZD-8 | GSK3 | CN1SC(=O)N(CC2=CC=CC=C2)C1=O | |

| RU-0423099 | DHE | IKKβ | [H][C@@]12CCC(=C)[C@]1([H])[C@H]1OC(=O)C(=C)[C@@H]1CCC2=C | |

| RU-0187005 | IKK-16 | IκB kinase | O=C(C1=CC=C(NC2=NC=CC(C3=CC4=C(C=CC=C4)S3)=N2)C=C1)N1CCC(N2CCCC2)CC1 | |

| RU-0279613 | AZ 960 | JAK | C1=C(C#N)C(N[C@H](C2=CC=C(F)C=C2)C)=NC(NC2=NNC(C)=C2)=C1F | |

| RU-0279340 | AT9283 | JAK/Aurora | O=C(NC1=CNN=C1C1=NC2=C(C=CC(CN3CCOCC3)=C2)N1)NC1CC1 | |

| RU-0422917 | BMS-911543 | JAK/B-Raf | CCN1C(C(=O)N(C2CC2)C2CC2)=CC2=C1N=C(NC1=NN(C)C(C)=C1)C1=C2N(C)C=N1 | |

| RU-0279550 | Momelotinib | JAK1/2 | C1=C(N2CCOCC2)C=CC(NC2=NC=CC(C3=CC=C(C(NCC#N)=O)C=C3)=N2)=C1 | |

| RU-0422858 | Cerdulatinib | JAK1/JAK2/JAK3/TYK2 and Syk | Cl.CCS(=O)(=O)N1CCN(C2=CC=C(NC3=NC(NC4CC4)=C(C(N)=O)C=N3)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0422774 | AZD 1480 | JAK2 | C[C@H](NC1=NC=C(Cl)C(NC2=NNC(C)=C2)=N1)C1=NC=C(F)C=N1 | |

| RU-0279667 | TG101209 | JAK2 | C1=C(S(NC(C)(C)C)(=O)=O)C=C(NC2=NC(NC3=CC=C(N4CCN(C)CC4)C=C3)=NC=C2C)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279611 | Gandotinib | JAK2 (V617F) | C1=C(CN2CCOCC2)C2=NC(C)=C(CC3=CC=C(Cl)C=C3F)N2N=C1NC1=CC(C)=NN1 | |

| RU-0186944 | BI 78D3 | JNK | O=C1NN=C(SC2=NC=C([N+]([O-])=O)S2)N1C1=CC=C2C(=C1)OCCO2 | |

| RU-0186854 | Halicin | JNK | NC1=NN=C(SC2=NC=C([N+]([O-])=O)S2)S1 | |

| RU-0422788 | GNE-7915 | LRRK2 | CCNC1=NC(NC2=CC(F)=C(C(=O)N3CCOCC3)C=C2OC)=NC=C1C(F)(F)F | |

| RU-0422765 | XMU MP 1 | MST 1/2 | CN1C2=C(SC=C2)C(=O)N(C)C2=CN=C(NC3=CC=C(S(N)(=O)=O)C=C3)N=C12 | |

| RU-0279719 | Torin 2 | mTOR | N1(C2=CC=CC(C(F)(F)F)=C2)C(=O)C=CC2=C1C1=CC(C3=CC=C(N)N=C3)=CC=C1N=C2 | |

| RU-0279624 | Torkinib | mTOR | N1=CN=C2C(=C1N)C(C1=CC3=C(N1)C=CC(O)=C3)=NN2C(C)C | |

| RU-0423121 | CCT196969 | pan-RAF/SRC/ LCK/p38 | CC(C)(C)C1=NN(C2=CC=CC=C2)C(NC(=O)NC2=CC=C(OC3=C4N=CC(=O)NC4=NC=C3)C=C2F)=C1 | |

| RU-0279460 | BX912 | PDK1 | N1(C(=O)NC2=CC=CC(NC3=NC=C(Br)C(NCCC4=CN=CN4)=N3)=C2)CCCC1 | |

| RU-0422754 | GNE-317 | PI3K | COC1(C2=C(C)C3=C(S2)C(N2CCOCC2)=NC(C2=CN=C(N)N=C2)=N3)COC1 | |

| RU-0422683 | PF-4989216 | PI3K | FC1=C(C2=C(C3=NC=NN3)SC(N3CCOCC3)=C2C#N)C=CC(C#N)=C1 | |

| RU-0422686 | AZD-8186 | PI3K | C[C@@H](NC1=CC(F)=CC(F)=C1)C1=CC(C(=O)N(C)C)=CC2=C1OC(N1CCOCC1)=CC2=O | |

| RU-0422905 | AZD8835 | PI3K | CCN1N=C(C2CCN(C(=O)CCO)CC2)N=C1C1=CN=C(N)C(C2=NN=C(C(C)(C)C)O2)=N1 | |

| RU-0422937 | AMG 319 | PI3K | C[C@H](NC1=C2N=CNC2=NC=N1)C1=C(C2=CC=CC=N2)N=C2C=C(F)C=CC2=C1 | |

| RU-0422939 | Taselisib | PI3K | CC(C)N1N=C(C)N=C1C1=CN2CCOC3=CC(C4=CN(C(C)(C)C(N)=O)N=C4)=CC=C3C2=N1 | |

| RU-0423198 | Pilaralisib | PI3K | COC1=CC(NC2=NC3=CC=CC=C3N=C2NS(=O)(=O)C2=CC=CC(NC(=O)C(C)(C)N)=C2)=C(Cl)C=C1 | |

| RU-0422980 | HS-173 | PI3K | CCOC(=O)C1=CN=C2C=CC(C3=CN=CC(NS(=O)(=O)C4=CC=CC=C4)=C3)=CN12 | |

| RU-0279862 | Duvelisib | PI3K | C1=CC=C2C(=C1Cl)C(=O)N(C1=CC=CC=C1)C([C@H](C)NC1=NC=NC3=C1N=CN3)=C2 | |

| RU-0279633 | PP121 | PI3K | C1(C2=NN(C3CCCC3)C3=C2C(N)=NC=N3)=CN=C2C(=C1)C=CN2 | |

| RU-0279699 | Apitolisib | PI3K | C1(C2=NC(N3CCOCC3)=C3C(=N2)C(C)=C(CN2CCN(C([C@@H](O)C)=O)CC2)S3)=CN=C(N)N=C1 | |

| RU-0279314 | Pictilisib | PI3K | C1(C2=NC(N3CCOCC3)=C3C(=N2)C=C(CN2CCN(S(=O)(=O)C)CC2)S3)=CC=CC2=C1C=NN2 | |

| RU-0279604 | Idelalisib | PI3K | C1=CC=C2C(=C1F)C(=O)N(C1=CC=CC=C1)C([C@@H](NC1=C3C(=NC=N1)NC=N3)CC)=N2 | |

| RU-0279614 | PIK-294 | PI3K | N1=CN=C2C(=C1N)C(C1=CC(O)=CC=C1)=NN2CC1=NC2=C(C(=O)N1C1=C(C)C=CC=C1)C(C)=CC=C2 | |

| RU-0422645 | SF2523r | PI3K/mTOR | O=C1C=C(N2CCOCC2)OC2=C1SC=C2C1=CC=C2OCCOC2=C1 | |

| RU-0279707 | Omipalisib | PI3K/mTOR | C1(S(=O)(=O)NC2=CC(C3=CC=C4N=CC=C(C5=CC=NN=C5)C4=C3)=CN=C2OC)=CC=C(F)C=C1F | |

| RU-0422677 | VS-5584 (SB2343) | PI3K/mTOR | CC(C)N1C(C)=NC2=C1N=C(N1CCOCC1)N=C2C1=CN=C(N)N=C1 | |

| RU-0422721 | Samotolisib | PI3K/mTOR | CO[C@@H](C)CN1C(=O)N(C)C2=C1C1=CC(C3=CC(C(C)(C)O)=CN=C3)=CC=C1N=C2 | |

| RU-0279660 | PF-04691502 | PI3K/mTOR | N1=C(N)N=C2C(=C1C)C=C(C1=CC=C(OC)N=C1)C(=O)N2[C@H]1CC[C@H](OCCO)CC1 | |

| RU-0422702 | GDC-0326 | PI3Kα | CC(C)N1N=CN=C1C1=CN2CCOC3=CC(O[C@@H](C)C(N)=O)=CC=C3C2=N1 | |

| RU-0422620 | AS-252424 | PI3Kγ | OC1=C(C2=CC=C(/C=C3∖SC(=O)NC3=O)O2)C=CC(F)=C1 | |

| RU-0423072 | GSK2292767 | PI3Kδ | COC1=C(NS(C)(=O)=O)C=C(C2=CC3=C(C=NN3)C(C3=NC=C(CN4C[C@H](C)O[C@H](C)C4)O3)=C2)C=N1 | |

| RU-0422921 | Go6976 (PD406976) | PKC | CN1C2=C(C=CC=C2)C2=C1C1=C(C3=C2C(=O)NC3)C2=C(C=CC=C2)N1CCC#N | |

| RU-0186834 | GF 109203X | PKC | CN(C)CCCN1C=C(C2=C(C3=CNC4=C3C=CC=C4)C(=O)NC2=O)C2=C1C=CC=C2 | |

| RU-0279747 | Sotrastaurin | PKC | N1C(=O)C(C2=CNC3=C2C=CC=C3)=C(C2=C3C=CC=CC3=NC(N3CCN(C)CC3)=N2)C1=O | |

| RU-0279733 | Go 6983 | PKC | C1(OC)=CC=C2C(=C1)C(C1=C(C3=CNC4=C3C=CC=C4)C(=O)NC1=O)=CN2CCCN(C)C | |

| RU-0423146 | Midostaurin | PKC, VEGFR2, c-kit, PDGFR, FLT3 | [H][C@]12C[C@@H](N(C)C(=O)C3=CC=CC=C3)[C@@H](OC)[C@](C)(O1)N1C3=C(C=CC=C3)C3=C4CNC(=O)C4=C4C5=C(C=CC=C5)N2C4=C13 | |

| RU-0422845 | Necrostatin-5 | RIP-3 | CC(C)S(=O)(=O)C1=CC=C2N=CC=C(NC3=CC4=C(SC=N4)C=C3)C2=C1 | |

| RU-0279739 | BI-D1870 | RSK1/2/3/4 | C1(O)=C(F)C=C(NC2=NC3=C(C=N2)N(C)C(=O)C(C)N3CCC(C)C)C=C1F | |

| RU-0186931 | PP2 | Src | CC(C)(C)N1N=C(C2=CC=C(Cl)C=C2)C2=C1N=CN=C2N | |

| RU-0186768 | PP1 | Src | CC1=CC=C(C2=NN(C(C)(C)C)C3=NC=NC(N)=C23)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279332 | Bosutinib | Src/Abl | N1=CC(C#N)=C(NC2=CC(OC)=C(Cl)C=C2Cl)C2=CC(OC)=C(OCCCN3CCN(C)CC3)C=C12 | |

| RU-0161884 | Dasatinib | Src/Abl | CC1=NC(NC2=NC=C(C(=O)NC3=C(C)C=CC=C3Cl)S2)=CC(N2CCN(CCO)CC2)=N1 | |

| RU-0422778 | RO9021 | Syk | CC1=CC=C(NC2=C(C(N)=O)N=NC(N[C@@H]3CCCC[C@@H]3N)=C2)N=C1C | |

| RU-0279519 | R406 | Syk | C1(OC)=C(OC)C=C(NC2=NC(NC3=NC4=C(C=C3)OC(C)(C)C(=O)N4)=C(F)C=N2)C=C1OC | |

| RU-0422901 | BAY 61-3606 | Syk | Cl.Cl.COC1=CC=C(C2=CC3=NC=CN3C(NC3=NC=CC=C3C(N)=O)=N2)C=C1OC | |

| RU-0423025 | MRT67307 | TBK1, MARK1-4, IKKε, NUAK1 | O=C(C1CCC1)NCCCNC1=NC(NC2=CC(CN3CCOCC3)=CC=C2)=NC=C1C1CC1 | |

| RU-0422916 | NCB-0846 | TNIK | O[C@H]1CC[C@@H](OC2=CC=CC3=C2N=C(NC2=CC=C4N=CNC4=C2)N=C3)CC1 | |

| RU-0422814 | XMD16-5 | TNK2 | CN1C2=C(C=CC=C2)C(=O)NC2=C1N=C(NC1=CC=C(N3CCC(O)CC3)C=C1)N=C2 | |

| RU-0422810 | OTS514 | TOPK | Cl.C[C@@H](CN)C1=CC=C(C2=C3C4=C(SC=C4)C(=O)NC3=C(C)C=C2O)C=C1 | |

| RU-0280020 | AZ-23 | TRK | C1(N[C@@H](C)C2=NC=C(F)C=C2)=NC=C(Cl)C(NC2=NNC(OC(C)C)=C2)=N1 | |

| Receptors | RU-0186853 | BNTX | δ₁-opioid | O=C1/C(=C/C2=CC=CC=C2)C[C@@]2(O)C3CC4=C5C(=C(O)C=C4)O[C@@H]1[C@]52CCN3CC1CC1 |

| RU-0423089 | Tirofiban | (GP) IIb/IIIA | O.Cl.CCCCS(=O)(=O)N[C@@H](CC1=CC=C(OCCCCC2CCNCC2)C=C1)C(O)=O | |

| RU-0279754 | NVP-BVU972 | c-Met | C1=CC2=NC=C(CC3=CC=C4C(=C3)C=CC=N4)N2N=C1C1=CN(C)N=C1 | |

| RU-0423074 | AMG 337 | c-Met | COCCOC1=CC2=C(C=CN([C@H](C)C3=NN=C4N3C=C(C3=CN(C)N=C3)C=C4F)C2=O)N=C1 | |

| RU-0423065 | Poziotinib | EGFR | COC1=CC2=C(C=C1OC1CCN(C(=O)C=C)CC1)C(NC1=CC=C(Cl)C(Cl)=C1F)=NC=N2 | |

| RU-0423002 | Naquotinib | EGFR | [H][C@@]1(OC2=NC(NC3=CC=C(N4CCC(N5CCN(C)CC5)CC4)C=C3)=C(C(N)=O)N=C2CC)CCN(C(=O)C=C)C1 | |

| RU-0422995 | LY2874455 | FGFR | C[C@@H](OC1=CC=C2NN=C(/C=C/C3=CN(CCO)N=C3)C2=C1)C1=C(Cl)C=NC=C1Cl | |

| RU-0186883 | PD 161570 | FGFR | ClC1=CC=CC(Cl)=C1C1=CC2=CN=C(NCCCCN(CC)CC)N=C2N=C1NC(NC(C)(C)C)=O | |

| RU-0423024 | Gilteritinib | FLT3 and AXL | CCC1=NC(C(N)=O)=C(NC2=CC=C(N3CCC(N4CCN(C)CC4)CC3)C(OC)=C2)N=C1NC1CCOCC1 | |

| RU-0001947 | 4431-00-9 | IGFR | C1(C(=O)O)=C/C(=C(∖C2=CC=C(O)C(C(=O)O)=C2)C2=CC(C(=O)O)=C(O)C=C2)C=CC1=O | |

| RU-0001676 | 2-APB | IP3 | NCCOB(C1=CC=CC=C1)C1=CC=CC=C1 | |

| RU-0423017 | BMS 536924 | IR and IGF1R | CC1=C2N=C(C3=C(NC[C@@H](O)C4=CC=CC(Cl)=C4)C=CNC3=O)NC2=CC(N2CCOCC2)=C1 | |

| RU-0423226 | MGCD-265 | Met, FLT-1, FLT-4, FK-1, RON | CN1C=NC(C2=CC3=NC=CC(OC4=CC=C(NC(=S)NC(=O)CC5=CC=CC=C5)C=C4F)=C3S2)=C1 | |

| RU-0279409 | Tivozanib | VEGFR | C1(OC2=CC=NC3=C2C=C(OC)C(OC)=C3)=CC=C(NC(=O)NC2=NOC(C)=C2)C(Cl)=C1 | |

| RU-0422989 | IMR-1 | Notch | CCOC(=O)COC1=CC=C(/C=C2∖SC(=S)NC2=O)C=C1OC | |

| Others | RU-0422866 | PD 151746 | Calpain | OC(=O)/C(S)=C/C1=CNC2=CC=C(F)C=C12 |

| RU-0000876 | Menadione | Cdc25 | C12=C(C(=O)C=C(C)C1=O)C=CC=C2 | |

| RU-0423108 | WS3 | EBP1 | CN1CCN(CC2=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C(NC(=O)NC3=CC=C(OC4=CC(NC(=O)C5CC5)=NC=N4)C=C3)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0423081 | WS26 | EBP1 | CN1CCN(CC2=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C(NC(=O)CC3=CC=C(OC4=CC(NC(=O)C5CC5)=NC=N4)C=C3)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0422897 | SBI-0640756 | eIF4G1 | FC1=CC(/C=C/C(=O)C2=C(C3=CC=CC=C3)C3=C(NC2=O)C=CC(Cl)=C3)=CN=C1 | |

| RU-0279914 | Edoxaban | Factor Xa | C(C(NC1=CC=C(Cl)C=N1)=O)(N[C@@H]1[C@H](NC(C2=NC3=C(S2)CN(C)CC3)=O)C[C@@H](C(N(C)C)=O)CC1)=O | |

| RU-0279505 | Apixaban | Factor Xa | N1=C(C(N)=O)C2=C(N1C1=CC=C(OC)C=C1)C(=O)N(C1=CC=C(N3C(=O)CCCC3)C=C1)CC2 | |

| RU-0423020 | 4μ8C | IRE1α | CC1=CC(=O)OC2=C(C=O)C(O)=CC=C12 | |

| RU-0177693 | (R)-Shikonin | PTEN | C12=C(O)C=CC(O)=C1C(=O)C=C([C@@H](CC=C(C)C)O)C2=O | |

| RU-0279768 | WP1066 | STAT3 | C(/C(=C/C1=NC(Br)=CC=C1)C#N)(=O)N[C@@H](C)C1=CC=CC=C1 | |

| RU-0279937 | Stattic | STAT3 | C1([N+](=O)[O-])=CC=C2C(=C1)S(=O)(=O)C=C2 | |

| RU-0422633 | MCB-613 | Steroid receptor coactivator | CCC1C/C(=C∖C2=CC=CN=C2)C(=O)/C(=C/C2=CN=CC=C2)C1 | |

| RU-0162051 | Levosimendan | Troponin C | C[C@@H]1CC(=O)NN=C1C1=CC=C(NN=C(C#N)C#N)C=C1 | |

| Phosphodiesterases | RU-0162129 | Anagrelide | PDE | ClC1=CC=C2N=C3NC(=O)CN3CC2=C1Cl |

| RU-0279503 | Pimobendan | PDE | C1=C2C(=CC=C1C1=NNC(=O)CC1C)NC(C1=CC=C(OC)C=C1)=N2 | |

| RU-0000311 | Papaverine | PDE | COC1=CC=C(CC2=C3C=C(OC)C(OC)=CC3=CC=N2)C=C1OC | |

| RU-0000724 | Cilostazol | PDE | N1(C2CCCCC2)N=NN=C1CCCCOC1=CC2=C(NC(=O)CC2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0083889 | Milrinone | PDE | C1(C#N)=CC(C2=CC=NC=C2)=C(C)NC1=O | |

| RU-0083815 | Zardaverine | PDE | N1=C(C2=CC=C(OC(F)F)C(OC)=C2)C=CC(=O)N1 | |

| RU-0001059 | IBMX | PDE | CC(C)CN1C2=C(N=CN2)C(=O)N(C)C1=O | |

| Ubiquitin pathway | RU-0423041 | b-AP15 | DUB (Ub-AMC) | [O-][N+](=O)C1=CC=C(/C=C2∖CN(C(=O)C=C)C/C(=C∖C3=CC=C([N+]([O-])=O)C=C3)C2=O)C=C1 |

| RU-0279930 | PR 619 | DUB | C1(SC#N)=C(N)N=C(N)C(SC#N)=C1 | |

| RU-0279626 | Degrasyn (WP1130) | DUB | C1(Br)=CC=CC(/C=C(/C(N[C@H](C2=CC=CC=C2)CCC)=O)C#N)=N1 | |

| RU-0423097 | VLX1570 | DUB (USP14) | [O-][N+](=O)C1=CC(/C=C2∖CN(C(=O)C=C)CC/C(=C∖C3=CC([N+]([O-])=O)=C(F)C=C3)C2=O) = CC=C1F | |

| RU-0279909 | NSC 697923 | E2 ubiquitin ligase (UBE2N) | C1=C(S(C2=CC=C([N+](=O)[O-])O2)(=O)=O)C=CC(C)=C1 | |

| RU-0280039 | SMER 3 | E3 ubiquitin ligase | C12 = NON=C1N=C1C(=N2)C(=O)C2=C1C=CC=C2 |

| Category . | Identifier . | Name . | Reported main target . | SMILES . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinases | RU-0422783 | Repotrectinib | ALK/ROS1/NTRK/Src/FAK | C[C@H]1CNC(=O)C2=C3N=C(N[C@H](C)C4=C(O1)C=CC(F)=C4)C=CN3N=C2 |

| RU-0423016 | Belizatinib (TSR-011) | ALK/TRK | CC(C)NC(=O)[C@H]1CC[C@@H](N2C3=CC(CN4CCC(C(C)(C)O)CC4)=CC=C3N/C2=N∖C(=O)C2=CC=C(F)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0422947 | Selonsertib | ASK1 | CC(C)N1C=NN=C1C1=CC=CC(NC(=O)C2=CC(N3C=NC(C4CC4)=C3)=C(C)C=C2F)=N1 | |

| RU-0279700 | TAK-901 | Aurora | C1N(C)CCC(NC(C2=C(C)C3=C(C(C4=CC(S(CC)(=O)=O)=CC=C4)=C2)C2=C(N3)N=CC(C)=C2)=O)C1 | |

| RU-0279648 | PF 03814735 | Aurora | C12=C(C=C(NC3=NC(NC4CCC4)=C(C(F)(F)F)C=N3)C=C1)[C@H]1CC[C@@H]2N1C(CNC(C)=O)=O | |

| RU-0279397 | CYC116 | Aurora | C1(NC2=CC=C(N3CCOCC3)C=C2)=NC=CC(C2=C(C)N=C(N)S2)=N1 | |

| RU-0279317 | Danusertib | Aurora | C1([C@H](C(N2CC3=C(C2)C(NC(=O)C2=CC=C(N4CCN(C)CC4)C=C2)=NN3)=O)OC)=CC=CC=C1 | |

| RU-0279484 | Hesperadin | Aurora | C1(NS(CC)(=O)=O)=CC=C2C(=C1)/C(=C(∖C1=CC=CC=C1)NC1=CC=C(CN3CCCCC3)C=C1)C(=O)N2 | |

| RU-0279329 | Alisertib | Aurora | C1=CC=C(F)C(C2=NCC3=C(C4=C2C=C(Cl)C=C4)N=C(NC2=CC(OC)=C(C(O)=O)C=C2)N=C3)=C1OC | |

| RU-0423010 | Acalabrutinib | BTK | CC#CC(=O)N1CCC[C@H]1C1=NC(C2=CC=C(C(=O)NC3=NC=CC=C3)C=C2)=C2N1C=CN=C2N | |

| RU-0423027 | RN486 | BTK | CN1CCN(C2=CN=C(NC3=CC(C4=CC=CC(N5C=CC6=CC(C7CC7)=CC(F)=C6C5=O)=C4CO)=CN(C)C3=O)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0422826 | ONO-4059 | BTK | NC1=C2N(C3=CC=C(OC4=CC=CC=C4)C=C3)C(=O)N(C3CCCN(C(=O)C=C)C3)C2=NC=N1 | |

| RU-0186817 | Amino purvalanol A | CDK | ClC1=CC(N)=CC(NC2=C3C(=NC(N[C@H](C(C)C)CO)=N2)N(C(C)C)C=N3)=C1 | |

| RU-0422987 | K03861 (AUZ454) | CDK | CN1CCN(CC2=CC=C(NC(=O)NC3=CC=C(OC4=NC(N)=NC=C4)C=C3)C=C2C(F)(F)F)CC1 | |

| RU-0186777 | (R)-DRF053 | CDK/CK1 | CC(C)N1C2=NC(N[C@H](CC)CO)=NC(NC3=CC(C4=NC=CC=C4)=CC=C3)=C2N=C1 | |

| RU-0279510 | AZD7762 | Chk1 | C1(F)=CC=CC(C2=CC(NC(N)=O)=C(C(N[C@@H]3CNCCC3)=O)S2)=C1 | |

| RU-0279783 | PF-477736 | Chk1 | C1=C(NC([C@@H](C2CCCCC2)N)=O)C=C2C3=C1C(=O)NN=CC3=C(C1=CN(C)N=C1)N2 | |

| RU-0186991 | PD 407824 | Chk1/Wee1 | O=C1NC(=O)C2=C3C(=CC(C4=CC=CC=C4)=C12)NC1=C3C=C(O)C=C1 | |

| RU-0423068 | PD0166285 | Chk1/Wee1 | CCN(CC)CCOC1=CC=C(NC2=NC3=C(C=N2)C=C(C2=C(Cl)C=CC=C2Cl)C(=O)N3C)C=C1 | |

| RU-0422703 | CC-115 | DNA-PK/TOR | CCN1C(=O)CNC2=NC=C(C3=C(C)N=C(C4=NNC=N4)C=C3)N=C12 | |

| RU-0279738 | TAE226 | FAK | C1(N2CCOCC2)=CC(OC)=C(NC2=NC(NC3=C(C(NC)=O)C=CC=C3)=C(Cl)C=N2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279636 | PF-562271 | FAK | C1=NC(N(C)S(=O)(C)=O)=C(CNC2=C(C(F)(F)F)C=NC(NC3=CC=C4C(=C3)CC(=O)N4)=N2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279535 | PF 573228 | FAK | N1C(=O)CCC2=C1C=CC(NC1=NC=C(C(F)(F)F)C(NCC3=CC=CC(S(=O)(=O)C)=C3)=N1)=C2 | |

| RU-0423060 | Defactinib | FAK/Pyk2 | CNC(=O)C1=CC=C(NC2=NC(NCC3=C(N(C)S(C)(=O)=O)N=CC=N3)=C(C(F)(F)F)C=N2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279636 | PF-562271 | FAK/Pyk2 | C1=NC(N(C)S(=O)(C)=O)=C(CNC2=C(C(F)(F)F)C=NC(NC3=CC=C4C(=C3)CC(=O)N4)=N2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279495 | TWS119 | GSK3 | C1=CC=C(OC2=NC=NC3=C2C=C(C2=CC=CC(N)=C2)N3)C=C1O | |

| RU-0422706 | TDZD-8 | GSK3 | CN1SC(=O)N(CC2=CC=CC=C2)C1=O | |

| RU-0423099 | DHE | IKKβ | [H][C@@]12CCC(=C)[C@]1([H])[C@H]1OC(=O)C(=C)[C@@H]1CCC2=C | |

| RU-0187005 | IKK-16 | IκB kinase | O=C(C1=CC=C(NC2=NC=CC(C3=CC4=C(C=CC=C4)S3)=N2)C=C1)N1CCC(N2CCCC2)CC1 | |

| RU-0279613 | AZ 960 | JAK | C1=C(C#N)C(N[C@H](C2=CC=C(F)C=C2)C)=NC(NC2=NNC(C)=C2)=C1F | |

| RU-0279340 | AT9283 | JAK/Aurora | O=C(NC1=CNN=C1C1=NC2=C(C=CC(CN3CCOCC3)=C2)N1)NC1CC1 | |

| RU-0422917 | BMS-911543 | JAK/B-Raf | CCN1C(C(=O)N(C2CC2)C2CC2)=CC2=C1N=C(NC1=NN(C)C(C)=C1)C1=C2N(C)C=N1 | |

| RU-0279550 | Momelotinib | JAK1/2 | C1=C(N2CCOCC2)C=CC(NC2=NC=CC(C3=CC=C(C(NCC#N)=O)C=C3)=N2)=C1 | |

| RU-0422858 | Cerdulatinib | JAK1/JAK2/JAK3/TYK2 and Syk | Cl.CCS(=O)(=O)N1CCN(C2=CC=C(NC3=NC(NC4CC4)=C(C(N)=O)C=N3)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0422774 | AZD 1480 | JAK2 | C[C@H](NC1=NC=C(Cl)C(NC2=NNC(C)=C2)=N1)C1=NC=C(F)C=N1 | |

| RU-0279667 | TG101209 | JAK2 | C1=C(S(NC(C)(C)C)(=O)=O)C=C(NC2=NC(NC3=CC=C(N4CCN(C)CC4)C=C3)=NC=C2C)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279611 | Gandotinib | JAK2 (V617F) | C1=C(CN2CCOCC2)C2=NC(C)=C(CC3=CC=C(Cl)C=C3F)N2N=C1NC1=CC(C)=NN1 | |

| RU-0186944 | BI 78D3 | JNK | O=C1NN=C(SC2=NC=C([N+]([O-])=O)S2)N1C1=CC=C2C(=C1)OCCO2 | |

| RU-0186854 | Halicin | JNK | NC1=NN=C(SC2=NC=C([N+]([O-])=O)S2)S1 | |

| RU-0422788 | GNE-7915 | LRRK2 | CCNC1=NC(NC2=CC(F)=C(C(=O)N3CCOCC3)C=C2OC)=NC=C1C(F)(F)F | |

| RU-0422765 | XMU MP 1 | MST 1/2 | CN1C2=C(SC=C2)C(=O)N(C)C2=CN=C(NC3=CC=C(S(N)(=O)=O)C=C3)N=C12 | |

| RU-0279719 | Torin 2 | mTOR | N1(C2=CC=CC(C(F)(F)F)=C2)C(=O)C=CC2=C1C1=CC(C3=CC=C(N)N=C3)=CC=C1N=C2 | |

| RU-0279624 | Torkinib | mTOR | N1=CN=C2C(=C1N)C(C1=CC3=C(N1)C=CC(O)=C3)=NN2C(C)C | |

| RU-0423121 | CCT196969 | pan-RAF/SRC/ LCK/p38 | CC(C)(C)C1=NN(C2=CC=CC=C2)C(NC(=O)NC2=CC=C(OC3=C4N=CC(=O)NC4=NC=C3)C=C2F)=C1 | |

| RU-0279460 | BX912 | PDK1 | N1(C(=O)NC2=CC=CC(NC3=NC=C(Br)C(NCCC4=CN=CN4)=N3)=C2)CCCC1 | |

| RU-0422754 | GNE-317 | PI3K | COC1(C2=C(C)C3=C(S2)C(N2CCOCC2)=NC(C2=CN=C(N)N=C2)=N3)COC1 | |

| RU-0422683 | PF-4989216 | PI3K | FC1=C(C2=C(C3=NC=NN3)SC(N3CCOCC3)=C2C#N)C=CC(C#N)=C1 | |

| RU-0422686 | AZD-8186 | PI3K | C[C@@H](NC1=CC(F)=CC(F)=C1)C1=CC(C(=O)N(C)C)=CC2=C1OC(N1CCOCC1)=CC2=O | |

| RU-0422905 | AZD8835 | PI3K | CCN1N=C(C2CCN(C(=O)CCO)CC2)N=C1C1=CN=C(N)C(C2=NN=C(C(C)(C)C)O2)=N1 | |

| RU-0422937 | AMG 319 | PI3K | C[C@H](NC1=C2N=CNC2=NC=N1)C1=C(C2=CC=CC=N2)N=C2C=C(F)C=CC2=C1 | |

| RU-0422939 | Taselisib | PI3K | CC(C)N1N=C(C)N=C1C1=CN2CCOC3=CC(C4=CN(C(C)(C)C(N)=O)N=C4)=CC=C3C2=N1 | |

| RU-0423198 | Pilaralisib | PI3K | COC1=CC(NC2=NC3=CC=CC=C3N=C2NS(=O)(=O)C2=CC=CC(NC(=O)C(C)(C)N)=C2)=C(Cl)C=C1 | |

| RU-0422980 | HS-173 | PI3K | CCOC(=O)C1=CN=C2C=CC(C3=CN=CC(NS(=O)(=O)C4=CC=CC=C4)=C3)=CN12 | |

| RU-0279862 | Duvelisib | PI3K | C1=CC=C2C(=C1Cl)C(=O)N(C1=CC=CC=C1)C([C@H](C)NC1=NC=NC3=C1N=CN3)=C2 | |

| RU-0279633 | PP121 | PI3K | C1(C2=NN(C3CCCC3)C3=C2C(N)=NC=N3)=CN=C2C(=C1)C=CN2 | |

| RU-0279699 | Apitolisib | PI3K | C1(C2=NC(N3CCOCC3)=C3C(=N2)C(C)=C(CN2CCN(C([C@@H](O)C)=O)CC2)S3)=CN=C(N)N=C1 | |

| RU-0279314 | Pictilisib | PI3K | C1(C2=NC(N3CCOCC3)=C3C(=N2)C=C(CN2CCN(S(=O)(=O)C)CC2)S3)=CC=CC2=C1C=NN2 | |

| RU-0279604 | Idelalisib | PI3K | C1=CC=C2C(=C1F)C(=O)N(C1=CC=CC=C1)C([C@@H](NC1=C3C(=NC=N1)NC=N3)CC)=N2 | |

| RU-0279614 | PIK-294 | PI3K | N1=CN=C2C(=C1N)C(C1=CC(O)=CC=C1)=NN2CC1=NC2=C(C(=O)N1C1=C(C)C=CC=C1)C(C)=CC=C2 | |

| RU-0422645 | SF2523r | PI3K/mTOR | O=C1C=C(N2CCOCC2)OC2=C1SC=C2C1=CC=C2OCCOC2=C1 | |

| RU-0279707 | Omipalisib | PI3K/mTOR | C1(S(=O)(=O)NC2=CC(C3=CC=C4N=CC=C(C5=CC=NN=C5)C4=C3)=CN=C2OC)=CC=C(F)C=C1F | |

| RU-0422677 | VS-5584 (SB2343) | PI3K/mTOR | CC(C)N1C(C)=NC2=C1N=C(N1CCOCC1)N=C2C1=CN=C(N)N=C1 | |

| RU-0422721 | Samotolisib | PI3K/mTOR | CO[C@@H](C)CN1C(=O)N(C)C2=C1C1=CC(C3=CC(C(C)(C)O)=CN=C3)=CC=C1N=C2 | |

| RU-0279660 | PF-04691502 | PI3K/mTOR | N1=C(N)N=C2C(=C1C)C=C(C1=CC=C(OC)N=C1)C(=O)N2[C@H]1CC[C@H](OCCO)CC1 | |

| RU-0422702 | GDC-0326 | PI3Kα | CC(C)N1N=CN=C1C1=CN2CCOC3=CC(O[C@@H](C)C(N)=O)=CC=C3C2=N1 | |

| RU-0422620 | AS-252424 | PI3Kγ | OC1=C(C2=CC=C(/C=C3∖SC(=O)NC3=O)O2)C=CC(F)=C1 | |

| RU-0423072 | GSK2292767 | PI3Kδ | COC1=C(NS(C)(=O)=O)C=C(C2=CC3=C(C=NN3)C(C3=NC=C(CN4C[C@H](C)O[C@H](C)C4)O3)=C2)C=N1 | |

| RU-0422921 | Go6976 (PD406976) | PKC | CN1C2=C(C=CC=C2)C2=C1C1=C(C3=C2C(=O)NC3)C2=C(C=CC=C2)N1CCC#N | |

| RU-0186834 | GF 109203X | PKC | CN(C)CCCN1C=C(C2=C(C3=CNC4=C3C=CC=C4)C(=O)NC2=O)C2=C1C=CC=C2 | |

| RU-0279747 | Sotrastaurin | PKC | N1C(=O)C(C2=CNC3=C2C=CC=C3)=C(C2=C3C=CC=CC3=NC(N3CCN(C)CC3)=N2)C1=O | |

| RU-0279733 | Go 6983 | PKC | C1(OC)=CC=C2C(=C1)C(C1=C(C3=CNC4=C3C=CC=C4)C(=O)NC1=O)=CN2CCCN(C)C | |

| RU-0423146 | Midostaurin | PKC, VEGFR2, c-kit, PDGFR, FLT3 | [H][C@]12C[C@@H](N(C)C(=O)C3=CC=CC=C3)[C@@H](OC)[C@](C)(O1)N1C3=C(C=CC=C3)C3=C4CNC(=O)C4=C4C5=C(C=CC=C5)N2C4=C13 | |

| RU-0422845 | Necrostatin-5 | RIP-3 | CC(C)S(=O)(=O)C1=CC=C2N=CC=C(NC3=CC4=C(SC=N4)C=C3)C2=C1 | |

| RU-0279739 | BI-D1870 | RSK1/2/3/4 | C1(O)=C(F)C=C(NC2=NC3=C(C=N2)N(C)C(=O)C(C)N3CCC(C)C)C=C1F | |

| RU-0186931 | PP2 | Src | CC(C)(C)N1N=C(C2=CC=C(Cl)C=C2)C2=C1N=CN=C2N | |

| RU-0186768 | PP1 | Src | CC1=CC=C(C2=NN(C(C)(C)C)C3=NC=NC(N)=C23)C=C1 | |

| RU-0279332 | Bosutinib | Src/Abl | N1=CC(C#N)=C(NC2=CC(OC)=C(Cl)C=C2Cl)C2=CC(OC)=C(OCCCN3CCN(C)CC3)C=C12 | |

| RU-0161884 | Dasatinib | Src/Abl | CC1=NC(NC2=NC=C(C(=O)NC3=C(C)C=CC=C3Cl)S2)=CC(N2CCN(CCO)CC2)=N1 | |

| RU-0422778 | RO9021 | Syk | CC1=CC=C(NC2=C(C(N)=O)N=NC(N[C@@H]3CCCC[C@@H]3N)=C2)N=C1C | |

| RU-0279519 | R406 | Syk | C1(OC)=C(OC)C=C(NC2=NC(NC3=NC4=C(C=C3)OC(C)(C)C(=O)N4)=C(F)C=N2)C=C1OC | |

| RU-0422901 | BAY 61-3606 | Syk | Cl.Cl.COC1=CC=C(C2=CC3=NC=CN3C(NC3=NC=CC=C3C(N)=O)=N2)C=C1OC | |

| RU-0423025 | MRT67307 | TBK1, MARK1-4, IKKε, NUAK1 | O=C(C1CCC1)NCCCNC1=NC(NC2=CC(CN3CCOCC3)=CC=C2)=NC=C1C1CC1 | |

| RU-0422916 | NCB-0846 | TNIK | O[C@H]1CC[C@@H](OC2=CC=CC3=C2N=C(NC2=CC=C4N=CNC4=C2)N=C3)CC1 | |

| RU-0422814 | XMD16-5 | TNK2 | CN1C2=C(C=CC=C2)C(=O)NC2=C1N=C(NC1=CC=C(N3CCC(O)CC3)C=C1)N=C2 | |

| RU-0422810 | OTS514 | TOPK | Cl.C[C@@H](CN)C1=CC=C(C2=C3C4=C(SC=C4)C(=O)NC3=C(C)C=C2O)C=C1 | |

| RU-0280020 | AZ-23 | TRK | C1(N[C@@H](C)C2=NC=C(F)C=C2)=NC=C(Cl)C(NC2=NNC(OC(C)C)=C2)=N1 | |

| Receptors | RU-0186853 | BNTX | δ₁-opioid | O=C1/C(=C/C2=CC=CC=C2)C[C@@]2(O)C3CC4=C5C(=C(O)C=C4)O[C@@H]1[C@]52CCN3CC1CC1 |

| RU-0423089 | Tirofiban | (GP) IIb/IIIA | O.Cl.CCCCS(=O)(=O)N[C@@H](CC1=CC=C(OCCCCC2CCNCC2)C=C1)C(O)=O | |

| RU-0279754 | NVP-BVU972 | c-Met | C1=CC2=NC=C(CC3=CC=C4C(=C3)C=CC=N4)N2N=C1C1=CN(C)N=C1 | |

| RU-0423074 | AMG 337 | c-Met | COCCOC1=CC2=C(C=CN([C@H](C)C3=NN=C4N3C=C(C3=CN(C)N=C3)C=C4F)C2=O)N=C1 | |

| RU-0423065 | Poziotinib | EGFR | COC1=CC2=C(C=C1OC1CCN(C(=O)C=C)CC1)C(NC1=CC=C(Cl)C(Cl)=C1F)=NC=N2 | |

| RU-0423002 | Naquotinib | EGFR | [H][C@@]1(OC2=NC(NC3=CC=C(N4CCC(N5CCN(C)CC5)CC4)C=C3)=C(C(N)=O)N=C2CC)CCN(C(=O)C=C)C1 | |

| RU-0422995 | LY2874455 | FGFR | C[C@@H](OC1=CC=C2NN=C(/C=C/C3=CN(CCO)N=C3)C2=C1)C1=C(Cl)C=NC=C1Cl | |

| RU-0186883 | PD 161570 | FGFR | ClC1=CC=CC(Cl)=C1C1=CC2=CN=C(NCCCCN(CC)CC)N=C2N=C1NC(NC(C)(C)C)=O | |

| RU-0423024 | Gilteritinib | FLT3 and AXL | CCC1=NC(C(N)=O)=C(NC2=CC=C(N3CCC(N4CCN(C)CC4)CC3)C(OC)=C2)N=C1NC1CCOCC1 | |

| RU-0001947 | 4431-00-9 | IGFR | C1(C(=O)O)=C/C(=C(∖C2=CC=C(O)C(C(=O)O)=C2)C2=CC(C(=O)O)=C(O)C=C2)C=CC1=O | |

| RU-0001676 | 2-APB | IP3 | NCCOB(C1=CC=CC=C1)C1=CC=CC=C1 | |

| RU-0423017 | BMS 536924 | IR and IGF1R | CC1=C2N=C(C3=C(NC[C@@H](O)C4=CC=CC(Cl)=C4)C=CNC3=O)NC2=CC(N2CCOCC2)=C1 | |

| RU-0423226 | MGCD-265 | Met, FLT-1, FLT-4, FK-1, RON | CN1C=NC(C2=CC3=NC=CC(OC4=CC=C(NC(=S)NC(=O)CC5=CC=CC=C5)C=C4F)=C3S2)=C1 | |

| RU-0279409 | Tivozanib | VEGFR | C1(OC2=CC=NC3=C2C=C(OC)C(OC)=C3)=CC=C(NC(=O)NC2=NOC(C)=C2)C(Cl)=C1 | |

| RU-0422989 | IMR-1 | Notch | CCOC(=O)COC1=CC=C(/C=C2∖SC(=S)NC2=O)C=C1OC | |

| Others | RU-0422866 | PD 151746 | Calpain | OC(=O)/C(S)=C/C1=CNC2=CC=C(F)C=C12 |

| RU-0000876 | Menadione | Cdc25 | C12=C(C(=O)C=C(C)C1=O)C=CC=C2 | |

| RU-0423108 | WS3 | EBP1 | CN1CCN(CC2=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C(NC(=O)NC3=CC=C(OC4=CC(NC(=O)C5CC5)=NC=N4)C=C3)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0423081 | WS26 | EBP1 | CN1CCN(CC2=C(C(F)(F)F)C=C(NC(=O)CC3=CC=C(OC4=CC(NC(=O)C5CC5)=NC=N4)C=C3)C=C2)CC1 | |

| RU-0422897 | SBI-0640756 | eIF4G1 | FC1=CC(/C=C/C(=O)C2=C(C3=CC=CC=C3)C3=C(NC2=O)C=CC(Cl)=C3)=CN=C1 | |

| RU-0279914 | Edoxaban | Factor Xa | C(C(NC1=CC=C(Cl)C=N1)=O)(N[C@@H]1[C@H](NC(C2=NC3=C(S2)CN(C)CC3)=O)C[C@@H](C(N(C)C)=O)CC1)=O | |

| RU-0279505 | Apixaban | Factor Xa | N1=C(C(N)=O)C2=C(N1C1=CC=C(OC)C=C1)C(=O)N(C1=CC=C(N3C(=O)CCCC3)C=C1)CC2 | |

| RU-0423020 | 4μ8C | IRE1α | CC1=CC(=O)OC2=C(C=O)C(O)=CC=C12 | |

| RU-0177693 | (R)-Shikonin | PTEN | C12=C(O)C=CC(O)=C1C(=O)C=C([C@@H](CC=C(C)C)O)C2=O | |

| RU-0279768 | WP1066 | STAT3 | C(/C(=C/C1=NC(Br)=CC=C1)C#N)(=O)N[C@@H](C)C1=CC=CC=C1 | |

| RU-0279937 | Stattic | STAT3 | C1([N+](=O)[O-])=CC=C2C(=C1)S(=O)(=O)C=C2 | |

| RU-0422633 | MCB-613 | Steroid receptor coactivator | CCC1C/C(=C∖C2=CC=CN=C2)C(=O)/C(=C/C2=CN=CC=C2)C1 | |

| RU-0162051 | Levosimendan | Troponin C | C[C@@H]1CC(=O)NN=C1C1=CC=C(NN=C(C#N)C#N)C=C1 | |

| Phosphodiesterases | RU-0162129 | Anagrelide | PDE | ClC1=CC=C2N=C3NC(=O)CN3CC2=C1Cl |

| RU-0279503 | Pimobendan | PDE | C1=C2C(=CC=C1C1=NNC(=O)CC1C)NC(C1=CC=C(OC)C=C1)=N2 | |

| RU-0000311 | Papaverine | PDE | COC1=CC=C(CC2=C3C=C(OC)C(OC)=CC3=CC=N2)C=C1OC | |

| RU-0000724 | Cilostazol | PDE | N1(C2CCCCC2)N=NN=C1CCCCOC1=CC2=C(NC(=O)CC2)C=C1 | |

| RU-0083889 | Milrinone | PDE | C1(C#N)=CC(C2=CC=NC=C2)=C(C)NC1=O | |

| RU-0083815 | Zardaverine | PDE | N1=C(C2=CC=C(OC(F)F)C(OC)=C2)C=CC(=O)N1 | |

| RU-0001059 | IBMX | PDE | CC(C)CN1C2=C(N=CN2)C(=O)N(C)C1=O | |

| Ubiquitin pathway | RU-0423041 | b-AP15 | DUB (Ub-AMC) | [O-][N+](=O)C1=CC=C(/C=C2∖CN(C(=O)C=C)C/C(=C∖C3=CC=C([N+]([O-])=O)C=C3)C2=O)C=C1 |

| RU-0279930 | PR 619 | DUB | C1(SC#N)=C(N)N=C(N)C(SC#N)=C1 | |

| RU-0279626 | Degrasyn (WP1130) | DUB | C1(Br)=CC=CC(/C=C(/C(N[C@H](C2=CC=CC=C2)CCC)=O)C#N)=N1 | |

| RU-0423097 | VLX1570 | DUB (USP14) | [O-][N+](=O)C1=CC(/C=C2∖CN(C(=O)C=C)CC/C(=C∖C3=CC([N+]([O-])=O)=C(F)C=C3)C2=O) = CC=C1F | |

| RU-0279909 | NSC 697923 | E2 ubiquitin ligase (UBE2N) | C1=C(S(C2=CC=C([N+](=O)[O-])O2)(=O)=O)C=CC(C)=C1 | |

| RU-0280039 | SMER 3 | E3 ubiquitin ligase | C12 = NON=C1N=C1C(=N2)C(=O)C2=C1C=CC=C2 |

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; AXL, AXL receptor tyrosine kinase; B-Raf, B-rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; BTK, Bruton's tyrosine kinase; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; c-kit, proto-oncogene c-kit; c-Met, mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor; Chk1, checkpoint kinase 1; CK1, casein kinase 1; DNA-PK, DNA-dependent protein kinase; δ1-opioid, delta-1 opioid receptor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; FK-1, Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1; FLT-1, Fms-like tyrosine kinase 1; FLT-4, Fms-like tyrosine kinase 4; FLT3, Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; IGF1R, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; IGFR, insulin-like growth factor receptor; IKKβ, IκB kinase beta; IKK, inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; IR, insulin receptor; IRE1α, inositol-requiring enzyme 1 alpha; JAK, Janus kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LCK, lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase; LRRK2, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2; MARK1-4, MAP/microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 1-4; Met, mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor; MST1/2, mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 and 2; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; Notch, notch receptor; NTRK, neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase; NUAK1, NUAK family kinase 1; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PDK1, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1; PKC, protein kinase C; p38, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase; Pky2, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; RIP-3, receptor-interacting protein kinase 3; RON, recepteur d'origine nantais; ROS1, c-ROS oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase; RSK1/2/3/4, ribosomal S6 kinase 1/2/3/4; Src, proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src; Syk, spleen tyrosine kinase; TBK1, TANK-binding kinase 1; TNIK, TRC8-associated nuclear factor-κB interacting kinase; TNK2, tyrosine kinase non-receptor 2; TOPK, tumor ovarian cancer kinase; TOR, target of rapamycin; TRK, tropomyosin receptor kinase; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

Compound selection criteria and DR studies

We selected compounds for further evaluation based on whether they were likely to be informative regarding fibrin-platelet interaction or novel signaling pathways involved in CR. As a result, we mostly focused on compounds whose targets were not previously reported as modulators of platelet function. Before proceeding, however, we used the data obtained using a cell viability test to ensure that the inhibition of CR was not because of cell toxicity. We eliminated 7 of 37 compounds we initially selected for further testing based on toxicity testing, leaving 30 compounds for further analysis.

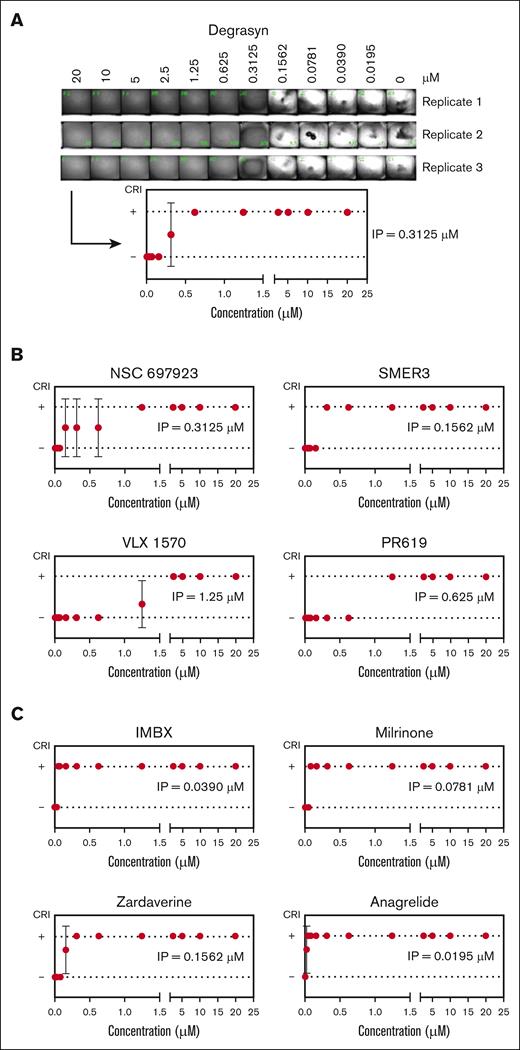

The dose-response (DR) assays followed the same steps as in the primary screen but with serial dilutions covering the ∼1000-fold range from 0.0195 to 20 μM. Based on the results after image processing, a concentration curve was constructed using the binary parameters used in the primary screen. Figure 3 shows the results using some of the ubiquitin and PDE inhibitors identified in the HTS. Degrasyn, a deubiquitinase inhibitor,44 exhibited inhibition from 20 to 0.625 μM (Figure 3A). At a concentration of 0.3125 μM, replicates 2 and 3 showed some evidence of retraction and thus were assigned a value of 0, whereas replicate 1, showed 100% inhibition and thus was assigned a 1. We defined the inflection point (IP), meant to be a surrogate for the concentration needed to achieve 50% inhibition, as the concentration in-between the 2 tested concentrations flanking the transition. The IP for degrasyn is thus 0.3125 μM. Some compounds converted from positive to negative in all replicates at a single dilution (eg, SMER3; Figure 3B), whereas other compounds showed inconsistent results over a range of concentrations (eg, NSC697923; Figure 3B), and in those cases the IP was defined as either the median or mean between the values, depending on whether the number of inconsistent results was an odd or even number. Figure 3C shows the DR curves of some PDE inhibitors identified in the LOPAC and DRL screen, along with their IP values. Table 3 contains the list of compounds tested in the DR assay and their respective IP concentrations.

DR studies lead to the identification of the IP for each selected compound. (A) Serial dilutions of the hit compound degrasyn, at the indicated final concentrations, were added to a 384-well plate. After conducting the miniaturized CR assay in triplicate, image analysis was performed (top) and binary results used to build a DR curve (bottom). (B) DR curves of other hit compounds identified in the primary screen as inhibitors of the ubiquitin pathway, along with their IPs. (C) DR curves of some of the hit compounds identified in the primary screen as inhibitors of the PDE, along with their IPs. Data reported as mean ± SD.

DR studies lead to the identification of the IP for each selected compound. (A) Serial dilutions of the hit compound degrasyn, at the indicated final concentrations, were added to a 384-well plate. After conducting the miniaturized CR assay in triplicate, image analysis was performed (top) and binary results used to build a DR curve (bottom). (B) DR curves of other hit compounds identified in the primary screen as inhibitors of the ubiquitin pathway, along with their IPs. (C) DR curves of some of the hit compounds identified in the primary screen as inhibitors of the PDE, along with their IPs. Data reported as mean ± SD.

Hit compounds selected for DR assays and their corresponding IP

| Category . | Name . | Reported main target . | IP . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinases | Danusertib | Aurora | 0.3125 μM |

| TWS119 | GSK3 | 0.0390 μM | |

| SF2523r | PI3K/mTOR | 0.625 μM | |

| NCB-0846 | TNIK | 0.625 μM | |

| XMD16-5 | TNK2 | 2.5 μM | |

| Receptors | BNTX | δ₁-opioid | 2.5 μM |

| NVP-BVU972 | c-Met | 1.875 | |

| AMG 337 | c-Met | 5 μM | |

| Poziotinib | EGFR | 2.5 μM | |

| Naquotinib | EGFR | 5 μM | |

| LY2874455 | FGFR | 0.625 μM | |

| PD 161570 | FGFR | 0.3125 μM | |

| Gilteritinib | FLT3 and AXL | 1.25 μM | |

| BMS 536924 | IR and IGF1R | 0.1562 μM | |

| MGCD-265 | Met, FLT-1, FLT-4, FK-1, RON | 2.5 μM | |

| Tivozanib | VEGFR | 1.25 μM | |

| IMR-1 | Notch | 2.5 μM | |

| Others | WS3 | EBP1 | 2.5 μM |

| WS26 | EBP1 | 2.5 μM | |

| SBI-0640756 | eIF4G1 | 1.25 μM | |

| Edoxaban | Factor Xa | 1.25 μM | |

| Apixaban | Factor Xa | 0.625 μM | |

| 4μ8C | IRE1α | 2.5 μM | |

| MCB-613 | Steroid receptor coactivator | 2.5 μM | |

| Phosphodiesterases | Milrinone | PDE | 0.0781 μM |

| Anagrelide | PDE | 0.0195 μM | |

| Zardaverine | PDE | 0.1562 μM | |

| IBMX | PDE | 0.039 μM | |

| Ubiquitin pathway | PR 619 | DUB | 1.25 μM |

| Degrasyn (WP1130) | DUB | 0.1562 μM | |

| VLX1570 | DUB (USP14) | 1.25 μM | |

| NSC 697923 | E2 ubiquitin ligase (UBE2N) | 0.625 μM | |

| SMER 3 | E3 ubiquitin ligase | 0.1562 μM |

| Category . | Name . | Reported main target . | IP . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinases | Danusertib | Aurora | 0.3125 μM |

| TWS119 | GSK3 | 0.0390 μM | |

| SF2523r | PI3K/mTOR | 0.625 μM | |

| NCB-0846 | TNIK | 0.625 μM | |

| XMD16-5 | TNK2 | 2.5 μM | |

| Receptors | BNTX | δ₁-opioid | 2.5 μM |

| NVP-BVU972 | c-Met | 1.875 | |

| AMG 337 | c-Met | 5 μM | |

| Poziotinib | EGFR | 2.5 μM | |

| Naquotinib | EGFR | 5 μM | |

| LY2874455 | FGFR | 0.625 μM | |

| PD 161570 | FGFR | 0.3125 μM | |

| Gilteritinib | FLT3 and AXL | 1.25 μM | |

| BMS 536924 | IR and IGF1R | 0.1562 μM | |

| MGCD-265 | Met, FLT-1, FLT-4, FK-1, RON | 2.5 μM | |

| Tivozanib | VEGFR | 1.25 μM | |

| IMR-1 | Notch | 2.5 μM | |

| Others | WS3 | EBP1 | 2.5 μM |

| WS26 | EBP1 | 2.5 μM | |

| SBI-0640756 | eIF4G1 | 1.25 μM | |

| Edoxaban | Factor Xa | 1.25 μM | |

| Apixaban | Factor Xa | 0.625 μM | |

| 4μ8C | IRE1α | 2.5 μM | |

| MCB-613 | Steroid receptor coactivator | 2.5 μM | |

| Phosphodiesterases | Milrinone | PDE | 0.0781 μM |

| Anagrelide | PDE | 0.0195 μM | |

| Zardaverine | PDE | 0.1562 μM | |

| IBMX | PDE | 0.039 μM | |

| Ubiquitin pathway | PR 619 | DUB | 1.25 μM |

| Degrasyn (WP1130) | DUB | 0.1562 μM | |

| VLX1570 | DUB (USP14) | 1.25 μM | |

| NSC 697923 | E2 ubiquitin ligase (UBE2N) | 0.625 μM | |

| SMER 3 | E3 ubiquitin ligase | 0.1562 μM |

EBP1, ErbB3-binding protein 1; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3.

Effect of fibrinogen inhibition with RGDW

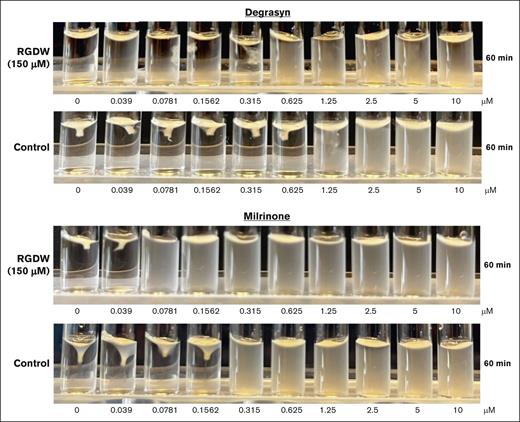

Our assay is performed in the presence of the RGDW peptide, which inhibits fibrinogen binding, platelet aggregation, and fibrinogen-mediated outside-in signaling, in order to bias the assay to identify compounds that selectively inhibit fibrin-mediated CR. To assess the impact of the peptide on the results, we performed a conventional CR assay using washed platelets from healthy donors in the presence or absence of the peptide. Figure 4 shows the effect of the RGDW in DR studies with 2 hit compounds, degrasyn44 and milrinone.35 In the peptide’s presence, both compounds inhibited CR at concentrations similar to those identified in the screening assay (degrasyn, 0.315 and 0.315 μM, respectively; milrinone, 0.039 and 0.781, μM, respectively). Omitting the peptide affected both compounds, with their IP values shifting upward approximately threefold (degrasyn + RGDW = 0.315 μM vs degrasyn without RGDW = 1.25 μM; and milrinone + RGDW = 0.039 μM vs milrinone without RGDW = 0.156 μM).

Effect of inhibition of fibrinogen binding with RGDW on potency of hit compounds. Washed platelets from healthy volunteers (3 × 108/mL) were treated or not, with RGDW (150 μM) for 20 minutes at room temperature and then transferred to an aggregometer cuvette containing the indicated dose of degrasyn (top) or milrinone (bottom), and a mixture of human α-thrombin (0.2 U/mL final concentration) and CaCl2 (1 mM final concentration) to initiate CR. Images were taken 60 minutes after of initiation of CR.

Effect of inhibition of fibrinogen binding with RGDW on potency of hit compounds. Washed platelets from healthy volunteers (3 × 108/mL) were treated or not, with RGDW (150 μM) for 20 minutes at room temperature and then transferred to an aggregometer cuvette containing the indicated dose of degrasyn (top) or milrinone (bottom), and a mixture of human α-thrombin (0.2 U/mL final concentration) and CaCl2 (1 mM final concentration) to initiate CR. Images were taken 60 minutes after of initiation of CR.

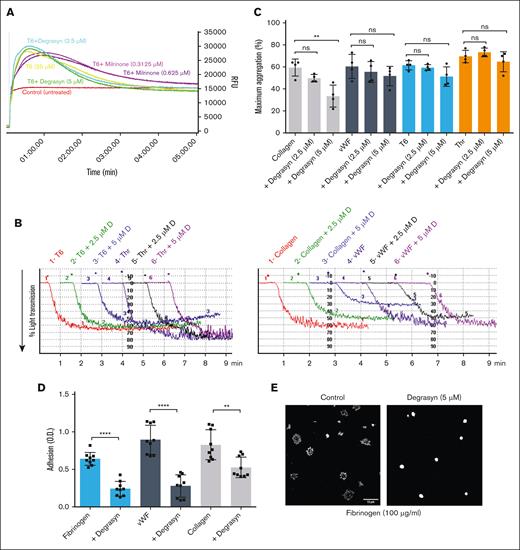

Degrasyn is identified as a novel compound with major effects on CR, platelet adhesion, and platelet aggregation initiated through C-type lectin-like type II (CLEC-2) and Fcγ receptor IIa but not protease activated receptor 1 (PAR-1), glycoprotein Ib, or glycoprotein VI (GPVI).

Because degrasyn has not been reported to affect platelet function, we selected it for additional secondary testing. We tested its effects at 2.5 and 5 μM because these concentrations are at least twice the IP of degrasyn and effectively inhibit CR in the absence of the RGDW peptide. At these concentrations degrasyn had no impact on PAR-1 activating peptide SFLLRN (T6)–induced Ca2+ mobilization (Figure 5A), and only minor effects on maximum platelet aggregation induced by von Willebrand factor (VWF), T6, and thrombin. Collagen-induced aggregation, in contrast, showed partial but significant (P = .006) inhibition by degrasyn at 5 μM (Figure 5B-C). In view of the partial impact of degrasyn on collagen-mediated aggregation, we tested the effect of degrasyn on platelet aggregation initiated through GPVI using convulxin and through the other immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-mediated receptors, CLEC-2 using fucoidin, and FcγRIIa using a monoclonal antibody to FcγRIIa crosslinked by another antibody. As shown in supplemental Figure 2, degrasyn at 2.5 and 5 μM did not significantly affect GPVI-mediated platelet aggregation but significantly inhibited aggregation initiated through both CLEC-2 and FcγRIIa. We then analyzed the effect of degrasyn on platelet adhesion to fibrinogen, VWF, and collagen, and found that 5 μM degrasyn significantly inhibited adhesion to the 3 substrates tested (P ≤ .0001 for fibrinogen and VWF; P = .0018 for collagen; Figure 5D). Microscopic examination of the morphology of adherent platelets showed that 5 μM degrasyn severely affected platelet spreading over fibrinogen (Figure 5E). In contrast to the spreading observed in untreated controls, degrasyn-treated platelets had a round appearance with no filopodia or lamellipodia formation. Lastly, we performed CR in platelet rich plasma to assess the impact of degrasyn in more physiological conditions. As seen on supplemental Figure 3, degrasyn partially inhibited CR at concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 10 μM and significantly inhibited CR at 20 μM. Collectively, our results suggest that inhibition of DUBs by degrasyn significantly affects CR; platelet adhesion and spreading; and collagen-, CLEC-2–, and FcγRIIa-induced platelet aggregation, whereas not having a significant impact on thrombin-, GPVI-, T6-, and VWF-induced platelet aggregation.

The DUB inhibitor degrasyn does not significantly affect Ca2+ mobilization, or thrombin-, T6 -, or VWF-induced platelet aggregation, but significantly affects collagen-induced platelet aggregation and platelet adhesion to fibrinogen, VWF, and collagen. (A) Washed platelets loaded with Calbryte 520 AM dye were untreated or treated with the indicated dose of degrasyn or milrinone for 20 minutes. Then, samples were treated with 25 μM of the PAR-1 receptor–activating peptide (SFLLRN; T6), and Ca2+ mobilization visualized for 5 minutes in a Hamamatsu FDSS/μCell fluorescence plate reader. (B) Washed platelets (3 × 108/mL) were treated with 2.5 μM or 5 μM degrasyn for 20 minutes at room temperature and then activated with either 10 μM of PAR-1 activating peptide (T6), 0.2 U/mL thrombin (Thr), 10 μg/mL collagen, or 3.76 μg/mL VWF + 1.8 mg/mL ristocetin in an aggregometer cuvette. Changes in light transmission were measured at 37°C with stirring. Representative aggregation tracing. (C) Quantitation and statistical analysis of 4 independent aggregation experiments. The data are reported as the mean ± SD of the maximal aggregation (MA). Student t test results: ∗∗P = .0062. (D) Washed platelets were either treated or untreated with 5 μM degrasyn for 20 minutes and then added to wells precoated with fibrinogen (10 μg/mL), VWF (5 μg/mL), or collagen (10 μg/mL). After 1 hour, the wells were washed, and platelet adhesion was assessed by measuring residual alkaline phosphatase activity. Results of 3 independent experiments, reported as mean ± SD adhesion units (optical density). Student t test results: ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗P = .0018. (E) Washed platelets (1 × 106/mL) were either untreated or treated with 5 μM degrasyn for 20 minutes and then allowed to adhere to cover slips coated with 100 μg/mL fibrinogen for 45 minutes, fixed, and labeled with antiubiquitin antibody P4D1 in combination with Alexa-594 secondary antibody. Images were acquired using an Abberior Facility Line confocal microscope using a 100× original magnification 1.45NA oil lens. Images were processed using FIJI/ImageJ for contrast and scale bar (10 μm). ns, not significant; RFU, relative fluorescence unit.

The DUB inhibitor degrasyn does not significantly affect Ca2+ mobilization, or thrombin-, T6 -, or VWF-induced platelet aggregation, but significantly affects collagen-induced platelet aggregation and platelet adhesion to fibrinogen, VWF, and collagen. (A) Washed platelets loaded with Calbryte 520 AM dye were untreated or treated with the indicated dose of degrasyn or milrinone for 20 minutes. Then, samples were treated with 25 μM of the PAR-1 receptor–activating peptide (SFLLRN; T6), and Ca2+ mobilization visualized for 5 minutes in a Hamamatsu FDSS/μCell fluorescence plate reader. (B) Washed platelets (3 × 108/mL) were treated with 2.5 μM or 5 μM degrasyn for 20 minutes at room temperature and then activated with either 10 μM of PAR-1 activating peptide (T6), 0.2 U/mL thrombin (Thr), 10 μg/mL collagen, or 3.76 μg/mL VWF + 1.8 mg/mL ristocetin in an aggregometer cuvette. Changes in light transmission were measured at 37°C with stirring. Representative aggregation tracing. (C) Quantitation and statistical analysis of 4 independent aggregation experiments. The data are reported as the mean ± SD of the maximal aggregation (MA). Student t test results: ∗∗P = .0062. (D) Washed platelets were either treated or untreated with 5 μM degrasyn for 20 minutes and then added to wells precoated with fibrinogen (10 μg/mL), VWF (5 μg/mL), or collagen (10 μg/mL). After 1 hour, the wells were washed, and platelet adhesion was assessed by measuring residual alkaline phosphatase activity. Results of 3 independent experiments, reported as mean ± SD adhesion units (optical density). Student t test results: ∗∗∗∗P < .0001; ∗∗P = .0018. (E) Washed platelets (1 × 106/mL) were either untreated or treated with 5 μM degrasyn for 20 minutes and then allowed to adhere to cover slips coated with 100 μg/mL fibrinogen for 45 minutes, fixed, and labeled with antiubiquitin antibody P4D1 in combination with Alexa-594 secondary antibody. Images were acquired using an Abberior Facility Line confocal microscope using a 100× original magnification 1.45NA oil lens. Images were processed using FIJI/ImageJ for contrast and scale bar (10 μm). ns, not significant; RFU, relative fluorescence unit.

Discussion

We chose 2 curated DRLs22 for our screen of CR inhibitors because there is information available on their safety and impact on therapeutic targets. Thus, they may be able to be repurposed for new indications rapidly, at low cost, and with higher approval rates.45-47 DRLs also can help define the biology of physiological and pathological processes by their diversity and defined targets. To focus our screen on compounds that interfere with CR downstream of platelet-fibrinogen interactions, we included the RGDW peptide, which is an inhibitor of fibrinogen-mediated platelet aggregation,20 but we recognized that this would not ensure that we would only identify inhibitors of CR that do not inhibit platelet aggregation because the assay relies on the activation of platelets by thrombin, thrombin-mediated signaling, thrombin-mediated fibrin formation, fibrin-platelet interaction, and intraplatelet signaling leading to actin-myosin–mediated force generation and CR. Thus, compounds affecting any 1 of these steps can inhibit CR, some of which will also inhibit platelet aggregation. Because our screen is based on thrombin activation, however, we hoped to diminish the likelihood of identifying compounds that selectively affect activators that operate through different pathways. We chose a concentration of 10 μM for each compound, which is likely to be above the concentration achievable in vivo, because we are primarily interested in defining the biology of the system. We did, however, identify compounds that are active at nanomolar concentrations, which are potentially achievable in vivo; these offer the best opportunity for repurposing.

DRLs often include many kinase inhibitors because of the large size of the kinome,48 their participation in numerous biological processes, their success as therapeutics, and their frequent broad off-target effects that may be beneficial in other diseases. It is thus not surprising that the majority of our hit compounds (86/127) are kinase inhibitors. In platelets, kinases play a crucial role in platelet function by regulating various signaling pathways49-54 and most of the kinases targeted by the hit compounds (eg, PI3K,55,56 Src,53 Syk,51,57 and PCK)58-60 have been well documented to affect platelet function, including inhibitory effects on both inside-out and outside-in signaling.18 Our HTS assay also identified compounds targeting kinases whose expression has not yet been identified in platelets, such as Aurora kinases,54 opening avenues for further analysis to assess whether these kinases play an unidentified role in platelet physiology, or whether the compounds have off-target effects on other molecules required for platelet function.

Seven PDE inhibitors, which increase the intraplatelet concentrations of the platelet inhibitors guanosine 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), were identified as hits in our screen (anagrelide, pimobendane, papaverine, cilostazol, milrinone, zardaverine, and IBMX). PDEs are expressed in variety of cells, which has led to the development of many FDA-approved PDE inhibitor drugs for several indications (prostatic hyperplasia, pulmonary arterial hypertension, psoriasis, heart failure, chronic obstructive lung disease, thromboembolic prophylaxis, peripheral vascular disease, neonatal apnea, and erectile dysfunction).61 Platelets contain 3 of the 11 members of the PDE family (PDE-2 [which hydrolyzes cAMP and cGMP equally], PDE-3 [which is relatively selective for cAMP], and PDE-5 [which is highly selective for cGMP]) and PDE inhibitors were shown to have antiplatelet effects >50 years ago.62-65 Dipyridamole, which inhibits both PDE-3 and PDE-5, is the only PDE inhibitor approved for its antiplatelet effect in decreasing thromboemboli in patients with mechanical valves when used in conjunction with anticoagulation.64 Dipyridamole is also used off-label in the prophylaxis of stroke in combination with aspirin. Cilostazol inhibits PDE-3 and also inhibits adenosine uptake.64 It inhibits a broad array of platelet function assays in vitro, and in vivo it enhances the antiplatelet effects of the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel.64 It demonstrates an antithrombotic effect in animal models but does not prolong the bleeding time. It improves the symptoms of patients with peripheral artery disease and claudication. Milrinone is a PDE-3 inhibitor approved for use in heart failure, but it inhibits platelet function at concentrations achieved in vivo.66,67 Anagrelide is a potent PDE-3 inhibitor that inhibits platelet function in vitro.64 Initial human studies found that it reduced platelet counts by an unknown mechanism, and this led to its approval for treating essential thrombocythemia.68 Zardaverine inhibits PDE-3 and PDE-4, and enhances the antiplatelet effects of adenylate cyclase activators in platelet aggregation.69 Pimobendan is a PDE-3 and partial PDE-5 inhibitor that inhibits platelet aggregation and enhances the antiplatelet effect of dipyridamole.70 The PDE-5 inhibitors approved for treating erectile dysfunction have also demonstrated variable antiplatelet effects.64,71 Gui et al characterized the platelets of mice with targeted deletion of PDE-5 and found elevated cGMP levels, increased tail bleeding times, and partially decreased FeCl3-induced thrombus formation and several assays of platelet function, including CR.72

Our finding of several deubiquitinase inhibitors among the hits is consistent with other reports of a role for ubiquitination in platelet function.73,74 Gupta et al reported that platelets contain both cytosolic and proteasome-associated deubiquitinase enzymes and that inhibiting these enzymes with 1 of several different inhibitors of variable specificity (PYR41, PR619, and b-AP15) resulted in increased protein ubiquitination and decreases in FeCl3-induced thrombus formation, platelet adhesion to collagen, platelet aggregation, and P-selectin expression.73 They concluded that quiescent platelets rapidly and continuously cycle ubiquitination of multiple proteins. They also studied the effect of inhibiting the proteasome with MG132 and/or bortezomib and found that they decreased FeCl3-induced thrombus formation; platelet aggregation induced by ristocetin and low-dose but not high-dose thrombin or T6; thrombin-induced adhesion and spreading on glass; microparticle formation in response to thrombin, adenosine 5’-diphosphate, and lipopolysaccharide; and CR.75 They also increased ubiquitination of the cytoskeletal proteins filamin A and talin-1. Bortezomib has also been shown to induce apoptosis and a procoagulant state in gel-filtered platelets.76 Bortezomib was included in our DRL but did not inhibit CR in our primary screen at 10 μM. Similarly, 3 other proteasome inhibitors (ixazomib, oprozomib, and delanzomib) were negative in our primary screen. Gupta et al used 30 μM MG132 and 40 μM bortezomib in their studies and so the difference in our results may be related to the dose used.

The ubiquitin E3 ligase c-Cbl has been well studied in platelets77 and has been established as a negative regulator of GPVI activation78 and an important scaffold in outside-in signaling.79 Mice deficient in c-Cbl do not show ubiquitination of Syk74 and have severe defects in platelet spreading and CR.79 Among the ubiquitinase-targeting compounds identified in our HTS, only PR619 has been previously tested in platelets.73,74,78 We focused our platelet function studies on the deubiquitinase drug degrasyn, a selective inhibitor of USP5, UCH-L1, USP9x, USP14, and UCH37,80-82 because we could not find any reports of its effects on platelet function. We found that it inhibits platelet CR and spreading, functions that are highly dependent on platelet outside-in signaling and cytoskeleton rearrangements. In contrast, degrasyn did not inhibit T6-induced Ca2+ mobilization, platelet aggregation in response to T6, thrombin, convulxin and VWF, responses that require inside-out signaling, αIIbβ3 activation, and ligand binding. High-dose collagen-induced aggregation was modestly but significantly affected by 5 μM degrasyn, but convulxin-induced aggregation, mediated by GPVI, showed little, if any, inhibition. In contrast, aggregation mediated by the 2 other ITAM receptors, CLEC-2 and FcγRIIa, was profoundly affected, suggesting that the latter 2 ITAM signaling pathways are dependent on proteasome/DUB-mediated signaling. This observation accords with studies by Unsworth et al who demonstrated that the activation of GPVI results in increased ubiquitination of proteins, including Syk, Lyn, and the Fc receptor γ-chain.74 Using trypsin cleavage to identify a characteristic tag of 2 glycine residues ligated to lysines modified by ubiquitination, they identified 1116 diGly-tagged peptides from 476 proteins in resting platelets, with many different sites of ubiquitination identified in cytoskeletal proteins (filamin and talin) and myosin.74 Thus, our studies of degrasyn add to our knowledge of the role of DUBs in platelet function at the interface of platelet aggregation and CR. Whether this reflects changes in protein degradation or the impact of ubiquitination on protein modifications and signaling remains to be determined. Degrasyn’s inhibition of platelet aggregation initiated through engagement of CLEC-2 and FcγRIIa indicates that it affects some signaling pathways leading to platelet aggregation, and thus it does not uniquely inhibit CR. However, because it has minimal effects on T6- and thrombin-induced platelet aggregation, its inhibition of CR appears to primarily be because of modulation of platelet function downstream of thrombin-induced platelet-fibrinogen interactions. This may involve signaling pathways that are also crucial for platelet aggregation mediated through engagement of CLEC-2 and FcγRIIa. Boylan et al demonstrated that FcγRIIa plays an important role in outside signaling initiated by platelet adhesion to fibrinogen and CR,83 and so the effect of degrasyn may be mediated, at least in part, by its effects on signaling through FcγRIIa. If other DUBs share degrasyn’s properties, this category of compounds may offer new avenues for targeted antiplatelet therapy.

It was notable that 2 factor Xa inhibitors, edoxaban and apixaban, were hits, with IPs of 1.25 and 0.625 μM, respectively. Edoxaban has been reported to decrease platelet aggregation in response to both thrombin and thrombin receptor cctivator peptide 2 hours after administration compared with baseline levels just before dosing in patients being treated for atrial fibrillation.84,85 Similar results were found with T6-induced platelet aggregation 2 hours after receiving apixaban or dabigatran.86 The mechanism(s) by which the factor Xa inhibitors reduce platelet aggregation is not established. Tsujimoto et al reported that although edoxaban and rivaroxaban did not inhibit collagen-induced platelet aggregation, they diminished the release of phosphorylated heat shock protein by decreasing HSP phosphorylation by P44/p42 MAPK.87 For comparison, the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran had no effect on platelet activation or aggregation with several different agonists, including T6.88