Key Points

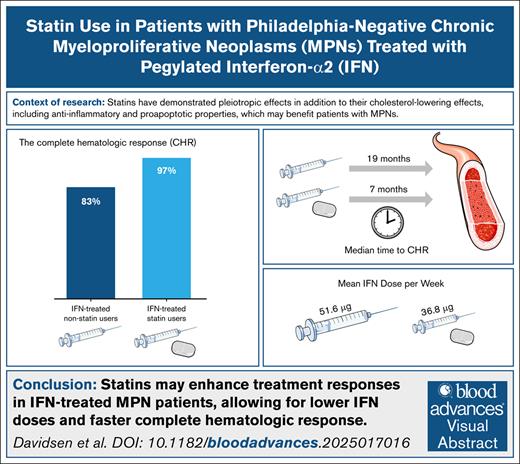

Statins enhance treatment responses in IFN-treated patients with MPN, allowing for lower IFN doses and faster CHR.

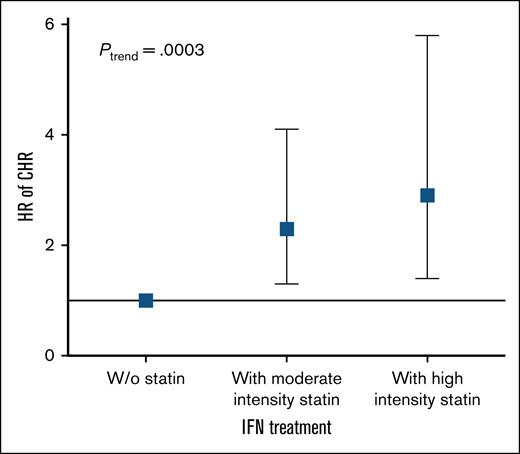

A dose-response relationship was observed, with increasing statin intensity associated with a faster CHR.

Visual Abstract

Chronic inflammation may be a key driving force in the development and progression of Philadelphia chromosome–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). Statins, commonly used to lower cholesterol, also possess antiproliferative, proapoptotic, and anti-inflammatory properties that may be beneficial in the treatment of patients with MPN. This retrospective cohort study investigated whether statin use, in addition to standard cytoreductive therapy, shortens the time required to achieve hematological and molecular responses, while allowing for lower cytoreductive drug dosages. A total of 129 patients were included, with 53 receiving statins from diagnosis. The study found that statin users achieved complete hematological response (CHR) significantly faster than nonusers (median time: 8 vs 18 months; hazard ratio [HR], 2.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4-3.1; P = .0003). Among patients treated with pegylated interferon-alfa2 (IFN-α2), the CHR rate was 97% in statin users vs 83% in nonusers (HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.5-3.9; P = .0004), and a higher proportion of statin users sustained CHR throughout follow-up. Additionally, IFN-treated statin users received a significantly lower mean dose of IFN-α2. A dose-response relationship was observed, with higher statin intensity associated with an increase of CHR. Furthermore, statin use was significantly associated with achieving a partial molecular response among IFN-α2-treated patients (HR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.1-6.0; P = .029). No significant association was observed in hydroxyurea (HU)-treated patients. These findings suggest that statins may enhance the efficacy of IFN-α2 in patients with MPN, while their benefit in HU-treated patients remains unclear. Prospective studies are warranted to further explore the therapeutic potential of statins in MPNs.

Introduction

Statins are potent inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the mevalonate pathway responsible for cholesterol biosynthesis. They are widely used for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease1; however, there is growing interest in repurposing statins as a safe and inexpensive therapeutic option for other conditions, particularly cancer.2 In addition to their cholesterol-lowering effects, statins have demonstrated antiproliferative, proapoptotic, antiangiogenic, and anti-inflammatory properties in a wide range of study designs, supporting their potential for therapeutic repurposing beyond cholesterol-lowering.3-7 These pleiotropic effects have also attracted interest in the context of hematological malignancies, including Philadelphia chromosome–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

MPNs, comprising essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), and myelofibrosis (MF), are chronic myeloid cancers that arise due to an acquired hematopoietic stem cell lesion, leading to excessive production of one or more mature blood cells in the myeloid lineage (erythrocytes, thrombocytes, and leukocytes).8-10 The driver mutations occur in the JAK2, CALR, or MPL genes, all of which activate the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in a direct or indirect manner.11,12 One of the most significant complications of ET and PV is an increased risk of thrombosis.13

In MPNs, statins have been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit JAK2V617F dependent cell growth in MPN cell lines. Additionally, the MPN associated JAK2V617F kinase, which is localized in lipid rafts, is inhibited by statins.14 Statin use has further been associated with a reduced frequency of MPNs in the general population,15 as well as with prolonged survival, a reduced incidence of thrombosis after an MPN diagnosis,16 and a decreased need for phlebotomies.17 However, no studies have investigated the impact of statins on hematological and molecular responses in patients with MPNs.

Chronic inflammation may be a key driving force in the development and progression of MPNs, particularly with regard to clonal expansion and the occurrence of complications, such as thrombosis and secondary malignancies.18-23 Several studies have implicated inflammatory cytokines in facilitating clonal expansion and disease progression,24-26 and tobacco smoking, an inflammatory stimulus, is associated with an increased risk of developing MPNs.27 Given the established link between inflammation and disease progression, targeting inflammatory pathways presents a promising therapeutic approach for patients with MPN. This is further substantiated by recent studies that have shown that ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor that potently inhibits the chronic inflammatory state crucial for clonal expansion and evolution, accelerates the achievement of minimal residual disease in an increasing number of patients with MPN when used in combination with pegylated interferon-alfa2 (IFN-α2).28 This combination therapy has been recognized as one of the most encouraging treatment modalities in MPNs to date, with the potential to significantly modify the disease course and perhaps even achieve long-term disease control or remission in a subset of patients.29-34

Given the anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic properties of statins, we hypothesized that statin use might enhance treatment response in patients receiving cytoreductive therapy.35,36 This study aimed to investigate whether statin use, in addition to standard cytoreductive treatment, shortens the time required to obtain hematological and molecular responses while allowing for a lower dosage of cytoreductive drugs.

Methods

Study design

The study was a single-institution, retrospective cohort study. We investigated a cohort of 129 patients diagnosed with MPN at the Department of Hematology at Zealand University Hospital in Denmark from 2011 to 2022, including a JAK2 subgroup consisting of all IFN-α2-treated patients with the JAK2 mutation and more than one JAK2 measurement (n = 59). The JAK2 subgroup was used to assess the effect of statin use on the JAK2 mutation variant allele frequency (VAF) and the molecular response. All patients were diagnosed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2008 or 2016 MPN classification.37,38 Data were collected from electronic medical records, and the baseline was defined as the time of diagnosis. Blood sample values and changes in cytoreductive treatment were collected at the time of diagnosis and afterward at ∼3-month intervals, depending on the frequency of outpatient clinic checkups. Cytoreductive therapy included IFN-α2 and hydroxyurea (HU).

We divided the patients into 2 groups: non–statin users and statin users. To be included in the statin treatment group, patients had to be treated with a statin from the time of diagnosis and continue throughout the follow-up period. Conversely, patients in the non–statin group must not have been treated with a statin at the time of diagnosis or initiated treatment during follow-up. We subdivided the patients into 4 groups according to statin use and cytoreductive treatment: statin users treated with IFN-α2, non–statin users treated with IFN-α2, statin users treated with HU, and non–statin users treated with HU for further analysis.

Hematological and molecular responses were assessed from blood cell counts according to the International Working Group-Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Research and Treatment and European LeukemiaNet criteria from 2013.39 A complete hematological response (CHR) was defined as follows:

For ET: platelet count (PLT) <400 × 109/L and white blood cell count <10 × 109/L

For PV: hematocrit <0.45 without phlebotomy, PLT <400 × 109/L, and white blood cell <10 × 109/L

For MF: hemoglobin ≥6.2 mmol/L and <upper normal limit (UNL), neutrophil count ≥1 × 109/L and <UNL, and PLT ≥100 × 109/L and <UNL.

These criteria had to be maintained for 12 weeks to qualify as a response.

In the primary analysis, the continuation of CHR was defined from the date of initial response to the first subsequent clinic visit at which blood values no longer fulfilled CHR criteria. This approach captured any deviation from CHR as an event, regardless of duration or subsequent recovery. To assess the clinical relevance of this measure, we conducted a supplementary analysis of durable CHR, where the event was defined as loss of CHR across at least 2 consecutive clinic visits spanning ≥6 months. This definition was applied to minimize the influence of transient fluctuations or dose-related changes and to reflect clinically meaningful loss of response more accurately.

A partial molecular response (PMR) was defined as a relative reduction of ≥50% from the JAK2 VAF at the time of diagnosis for patients with an initial JAK2 VAF of ≥20% (n = 43). A complete molecular response was defined as a reduction below 1% of a preexisting JAK2 mutation.

Smoking habits were categorized as current, former, and never smokers. Alcohol consumption was categorized according to the Danish Health Authority recommendations40 as or 10 units of alcohol per week, where 1 unit contains 12 g of alcohol. Hypertension was defined by usage of antihypertensive drugs. Thromboembolic events occurring prior to diagnosis were recorded. The type of statin treatment administered to patients was divided into 2 categories: moderate intensity and high intensity, following the guidelines outlined by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association for the management of blood cholesterol.41 Moderate intensity statin treatment typically reduces low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) by 30% to 49%, and includes atorvastatin (10-20 mg), simvastatin (20-40 mg), or rosuvastatin (5-10 mg). High-intensity statin treatment generally results in a reduction of ≥50% and includes atorvastatin 40-80 mg.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 4.3.2). Patient characteristics were analyzed using a chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data and a Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous data. CHR and PMR was investigated using time-to-event analysis with the Kaplan-Meier curves with accompanying event probabilities and log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (95% CI) for CHR, PMR, and statin treatment intensity were calculated using the Cox proportional hazard regression model. A multivariable analysis was performed, adjusted for age, sex, and smoking. Differences in treatment were compared using a chi-squared test for categorical data and a t-test for continuous data. Statistical significance was considered as P values of <0.05.

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Results

Complete cohort: the effect of statin use on hematological response and cytoreductive treatment

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The cohort included 129 patients: 76 non–statin users and 53 statin users. There were significant differences in smoking status, comorbidities, and total cholesterol and LDL-C. There were no significant differences in baseline blood counts or JAK2 VAF (%) among the 2 groups.

Baseline characteristics of all patients

| Characteristics . | Without statin (N = 76) . | With statin (N = 53) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 60.4 (51.8-68.7) | 66.9 (57.7-71.9) | .05 |

| Sex, male | 36 (47.4) | 28 (52.8) | .594 |

| MPN subtype | |||

| ET | 23 (30.3) | 20 (37.7) | .687 |

| PV | 43 (56.6) | 25 (47.2) | |

| Prefibrotic myelofibrosis | 5 (6.6) | 5 (9.4) | |

| Primary myelofibrosis | 5 (6.6) | 3 (5.7) | |

| Driver mutation | |||

| JAK2V617F | 57 (75.0) | 44 (83.0) | .765 |

| CALR | 13 (17.2) | 5 (9.4) | |

| MPL | 3 (3.9) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Triple negative | 3 (3.9) | 3 (5.7) | |

| Follow-up time, y | 4.6 (2.2-6.5) | 4.9 (2.3-6.8) | .610 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 49 (64.5) | 24 (45.3) | .041 |

| Former | 15 (19.7) | 21 (39.6) | |

| Current | 12 (15.8) | 8 (15.1) | |

| Alcohol, units per week | |||

| ≤10 | 34 (44.7) | 23 (43.4) | .795 |

| >10 | 11 (14.5) | 9 (17.0) | |

| Missing | 31 (40.8) | 21 (39.6) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.8 (22.6-27.4) | 25.3 (22.3-28.0) | .843 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension∗ | 25 (32.9) | 38 (71.7) | <.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 3 (4) | 10 (18.9) | .007 |

| Thromboembolic event† | 19 (25) | 27 (50.9) | .003 |

| Statin treatment | |||

| Moderate intensity‡ | 33 (62.3) | <.001 | |

| High intensity§ | 20 (37.7) | ||

| Cytoreductive treatment | |||

| HU | 23 (30.3) | 23 (43.4) | .139 |

| Pegylated IFN-α2 | 53 (69.7) | 30 (56.6) | |

| Laboratory test | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 16.0 (14.2-18.5) | 15.3 (13.7-17.2) | .229 |

| Erythrocytes, ×1012/L | 5.6 (4.8-6.8) | 5.2 (4.6-6.0) | .074 |

| WBC, ×109/L | 9.8 (7.5-10.5) | 10.1 (8.2-12.8) | .521 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 680 (451-888) | 596 (516-753) | .405 |

| JAK2V617F, % | 34.0 (11.8-46.8) | 34.1 (18.0-49.5) | .719 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.9 (4.4-5.7) | 4.0 (3.4-4.5) | <.001 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.9 (2.4-3.3) | 1.8 (1.6-2.3) | <.001 |

| Characteristics . | Without statin (N = 76) . | With statin (N = 53) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 60.4 (51.8-68.7) | 66.9 (57.7-71.9) | .05 |

| Sex, male | 36 (47.4) | 28 (52.8) | .594 |

| MPN subtype | |||

| ET | 23 (30.3) | 20 (37.7) | .687 |

| PV | 43 (56.6) | 25 (47.2) | |

| Prefibrotic myelofibrosis | 5 (6.6) | 5 (9.4) | |

| Primary myelofibrosis | 5 (6.6) | 3 (5.7) | |

| Driver mutation | |||

| JAK2V617F | 57 (75.0) | 44 (83.0) | .765 |

| CALR | 13 (17.2) | 5 (9.4) | |

| MPL | 3 (3.9) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Triple negative | 3 (3.9) | 3 (5.7) | |

| Follow-up time, y | 4.6 (2.2-6.5) | 4.9 (2.3-6.8) | .610 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 49 (64.5) | 24 (45.3) | .041 |

| Former | 15 (19.7) | 21 (39.6) | |

| Current | 12 (15.8) | 8 (15.1) | |

| Alcohol, units per week | |||

| ≤10 | 34 (44.7) | 23 (43.4) | .795 |

| >10 | 11 (14.5) | 9 (17.0) | |

| Missing | 31 (40.8) | 21 (39.6) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.8 (22.6-27.4) | 25.3 (22.3-28.0) | .843 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension∗ | 25 (32.9) | 38 (71.7) | <.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 3 (4) | 10 (18.9) | .007 |

| Thromboembolic event† | 19 (25) | 27 (50.9) | .003 |

| Statin treatment | |||

| Moderate intensity‡ | 33 (62.3) | <.001 | |

| High intensity§ | 20 (37.7) | ||

| Cytoreductive treatment | |||

| HU | 23 (30.3) | 23 (43.4) | .139 |

| Pegylated IFN-α2 | 53 (69.7) | 30 (56.6) | |

| Laboratory test | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 16.0 (14.2-18.5) | 15.3 (13.7-17.2) | .229 |

| Erythrocytes, ×1012/L | 5.6 (4.8-6.8) | 5.2 (4.6-6.0) | .074 |

| WBC, ×109/L | 9.8 (7.5-10.5) | 10.1 (8.2-12.8) | .521 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 680 (451-888) | 596 (516-753) | .405 |

| JAK2V617F, % | 34.0 (11.8-46.8) | 34.1 (18.0-49.5) | .719 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.9 (4.4-5.7) | 4.0 (3.4-4.5) | <.001 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.9 (2.4-3.3) | 1.8 (1.6-2.3) | <.001 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (IQR).

BMI, body mass index; WBC, white blood cell.

Defined by usage of antihypertensive drugs.

Thromboembolic events prior to diagnosis recorded; Cerebral infarct, acute myocardial infarct (STEMI and NSTEMI), deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, transient ischemic attack and amaurosis fugax.

Includes atorvastatin 10-20 mg, simvastatin 20-40 mg, and rosuvastatin 5-10 mg.

Includes atorvastatin 40-80 mg.

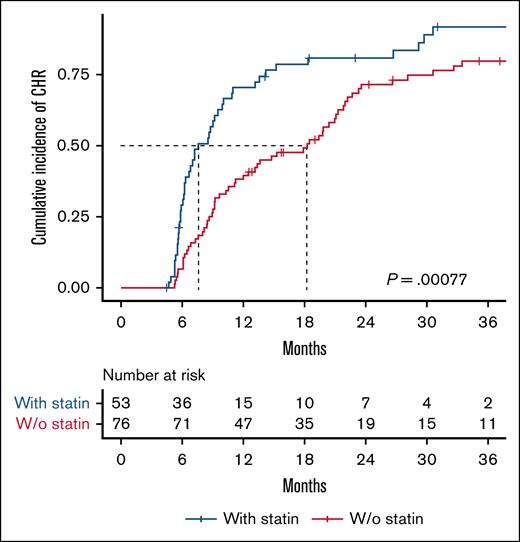

We assessed the difference in the cumulative incidence of CHR between non–statin users and statin users (Figure 1). Among 129 patients with a median follow-up time of 4.7 years (range, 1.7-12.1), 104 (81%) achieved a CHR. The CHR was 78% in non–statin users and 85% in statin users, with a median time to CHR of 18 months and 8 months, respectively (P = .00077). Statin use was significantly associated with achieving a CHR with a HR (95% CI) of 2.1 (1.4-3.1), P = .0003 (Figure 3).

Statin use is associated with faster achievement of CHR in patients with MPN. Kaplan-Meier plot showing time to CHR stratified by statin use. The median time to CHR was 8 months for statin users and 18 months for non–statin users. The log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative incidence of CHR. W/o, without.

Statin use is associated with faster achievement of CHR in patients with MPN. Kaplan-Meier plot showing time to CHR stratified by statin use. The median time to CHR was 8 months for statin users and 18 months for non–statin users. The log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative incidence of CHR. W/o, without.

Baseline characteristics according to cytoreductive treatment are shown in Table 2. The cohort was categorized as follows: 53 IFN-α2-treated non–statin users, 30 IFN-α2-treated statin users, 23 HU-treated non–statin users, and 23 HU-treated statin users. Patients treated with HU were older and included a higher proportion of women compared to those treated with IFN-α2. More patients treated with a statin had hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and thromboembolic events prior to MPN diagnosis, as well as a lower total cholesterol and LDL-C, compared with patients not treated with a statin. There were no significant differences in baseline blood counts or JAK2 VAF (%) among the 4 groups.

Baseline characteristics according to cytoreductive treatment

| Characteristics . | IFN-α2 (N = 53) . | IFN-α2 + Statin (N = 30) . | HU (N = 23) . | HU + Statin (N = 23) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 57.3 (51.2-64.6) | 60.3 (54.9-69.2) | 70.3 (65.9-78.6) | 74.1 (69.6-77.3) | <.001 |

| Sex, male | 31 (58.5) | 20 (66.7) | 5 (21.7) | 8 (34.8) | .002 |

| MPN subtype | |||||

| ET | 15 (28.3) | 12 (40) | 8 (34.8) | 8 (34.8) | .617 |

| PV | 30 (56.6) | 13 (43.3) | 13 (56.5) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Prefibrotic myelofibrosis | 3 (5.7) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (8.7) | 3 (13) | |

| Primary myelofibrosis | 5 (9.4) | 3 (10) | 0 | 0 | |

| Driver mutation | |||||

| JAK2V617F | 39 (73.6) | 24 (80) | 18 (78.3) | 20 (87) | .603 |

| CALR | 11 (20.8) | 4 (13.3) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.4) | |

| MPL | 2 (3.8) | 0 | 1 (4.4) | 1 (4.4) | |

| Triple negative | 1 (1.9) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.4) | |

| Follow-up time, years | 4.8 (2.3-6.5) | 5.6 (2.8-7.1) | 4.5 (1.6-6.5) | 3.9 (1.7-5.6) | .514 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 37 (69.8) | 16 (53.3) | 12 (52.2) | 8 (34.8) | .054 |

| Former | 10 (18.9) | 9 (30) | 5 (21.7) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Current | 6 (11.3) | 5 (16.7) | 6 (26.1) | 3 (13) | |

| Alcohol, units per week | |||||

| ≤10 | 23 (43.4) | 11 (36.7) | 11 (47.8) | 12 (52.2) | .650 |

| >10 | 9 (17) | 6 (20) | 2 (8.7) | 3 (13) | |

| Missing | 21 (39.6) | 13 (56.5) | 10 (43.5) | 8 (34.8) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.2 (22.6-27.7) | 25.9 (23.7-28.8) | 23.8 (22.5-27.4) | 23.9 (22.1-27) | .354 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension∗ | 13 (24.5) | 20 (66.7) | 12 (52.2) | 18 (78.3) | <.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 3 (5.7) | 8 (26.7) | 0 | 2 (8.7) | .006 |

| Thromboembolic event† | 15 (28.3) | 13 (43.3) | 4 (17.4) | 14 (60.9) | .008 |

| Statin treatment | .285 | ||||

| Moderate intensity‡ | 18 (60) | 15 (65.2) | |||

| High intensity§ | 12 (40) | 8 (34.8) | |||

| Laboratory test | |||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 16.6 (13.9-18.2) | 15.5 (13.5-18.4) | 15.5 (14.2-19.2) | 15.3 (14-16.8) | .628 |

| Erythrocytes, ×1012/L | 5.6 (4.7-6.6) | 5.1 (4.7-6.1) | 5.6 (5.0-7.2) | 5.3 (4.6-6.0) | .284 |

| WBC, ×109/L | 9.3 (7.1-11.8) | 10.3 (8.3-13.0) | 10.1 (8.5-14.3) | 9.7 (8.3-11.6) | .605 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 634 (478-862) | 594 (523-750) | 715 (429-916) | 603 (506-736) | .768 |

| JAK2V617F, % | 35.2 (13.3-48) | 36.6 (20.5-50) | 31.8 (13-44.3) | 31.2 (16.8-40) | .922 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.6 (4.2-5.3) | 3.8 (3.2-4.3) | 5.4 (4.7-5.9) | 4.1 (3.5-4.6) | <.001 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.7 (2.1-3.3) | 1.7 (1.5-2.3) | 3.0 (2.8-3.3) | 1.9 (1.7-2.1) | <.001 |

| Characteristics . | IFN-α2 (N = 53) . | IFN-α2 + Statin (N = 30) . | HU (N = 23) . | HU + Statin (N = 23) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 57.3 (51.2-64.6) | 60.3 (54.9-69.2) | 70.3 (65.9-78.6) | 74.1 (69.6-77.3) | <.001 |

| Sex, male | 31 (58.5) | 20 (66.7) | 5 (21.7) | 8 (34.8) | .002 |

| MPN subtype | |||||

| ET | 15 (28.3) | 12 (40) | 8 (34.8) | 8 (34.8) | .617 |

| PV | 30 (56.6) | 13 (43.3) | 13 (56.5) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Prefibrotic myelofibrosis | 3 (5.7) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (8.7) | 3 (13) | |

| Primary myelofibrosis | 5 (9.4) | 3 (10) | 0 | 0 | |

| Driver mutation | |||||

| JAK2V617F | 39 (73.6) | 24 (80) | 18 (78.3) | 20 (87) | .603 |

| CALR | 11 (20.8) | 4 (13.3) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.4) | |

| MPL | 2 (3.8) | 0 | 1 (4.4) | 1 (4.4) | |

| Triple negative | 1 (1.9) | 2 (6.7) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.4) | |

| Follow-up time, years | 4.8 (2.3-6.5) | 5.6 (2.8-7.1) | 4.5 (1.6-6.5) | 3.9 (1.7-5.6) | .514 |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 37 (69.8) | 16 (53.3) | 12 (52.2) | 8 (34.8) | .054 |

| Former | 10 (18.9) | 9 (30) | 5 (21.7) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Current | 6 (11.3) | 5 (16.7) | 6 (26.1) | 3 (13) | |

| Alcohol, units per week | |||||

| ≤10 | 23 (43.4) | 11 (36.7) | 11 (47.8) | 12 (52.2) | .650 |

| >10 | 9 (17) | 6 (20) | 2 (8.7) | 3 (13) | |

| Missing | 21 (39.6) | 13 (56.5) | 10 (43.5) | 8 (34.8) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.2 (22.6-27.7) | 25.9 (23.7-28.8) | 23.8 (22.5-27.4) | 23.9 (22.1-27) | .354 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension∗ | 13 (24.5) | 20 (66.7) | 12 (52.2) | 18 (78.3) | <.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 3 (5.7) | 8 (26.7) | 0 | 2 (8.7) | .006 |

| Thromboembolic event† | 15 (28.3) | 13 (43.3) | 4 (17.4) | 14 (60.9) | .008 |

| Statin treatment | .285 | ||||

| Moderate intensity‡ | 18 (60) | 15 (65.2) | |||

| High intensity§ | 12 (40) | 8 (34.8) | |||

| Laboratory test | |||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 16.6 (13.9-18.2) | 15.5 (13.5-18.4) | 15.5 (14.2-19.2) | 15.3 (14-16.8) | .628 |

| Erythrocytes, ×1012/L | 5.6 (4.7-6.6) | 5.1 (4.7-6.1) | 5.6 (5.0-7.2) | 5.3 (4.6-6.0) | .284 |

| WBC, ×109/L | 9.3 (7.1-11.8) | 10.3 (8.3-13.0) | 10.1 (8.5-14.3) | 9.7 (8.3-11.6) | .605 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 634 (478-862) | 594 (523-750) | 715 (429-916) | 603 (506-736) | .768 |

| JAK2V617F, % | 35.2 (13.3-48) | 36.6 (20.5-50) | 31.8 (13-44.3) | 31.2 (16.8-40) | .922 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.6 (4.2-5.3) | 3.8 (3.2-4.3) | 5.4 (4.7-5.9) | 4.1 (3.5-4.6) | <.001 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.7 (2.1-3.3) | 1.7 (1.5-2.3) | 3.0 (2.8-3.3) | 1.9 (1.7-2.1) | <.001 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (IQR).

BMI, body mass index; WBC, white blood cell.

Defined by usage of antihypertensive drugs.

Thromboembolic events prior to diagnosis recorded; Cerebral infarct, acute myocardial infarct (STEMI and NSTEMI), deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, transient ischemic attack and amaurosis fugax.

Includes atorvastatin 10-20 mg, simvastatin 20-40 mg and rosuvastatin 5-10 mg.

Includes atorvastatin 40-80 mg.

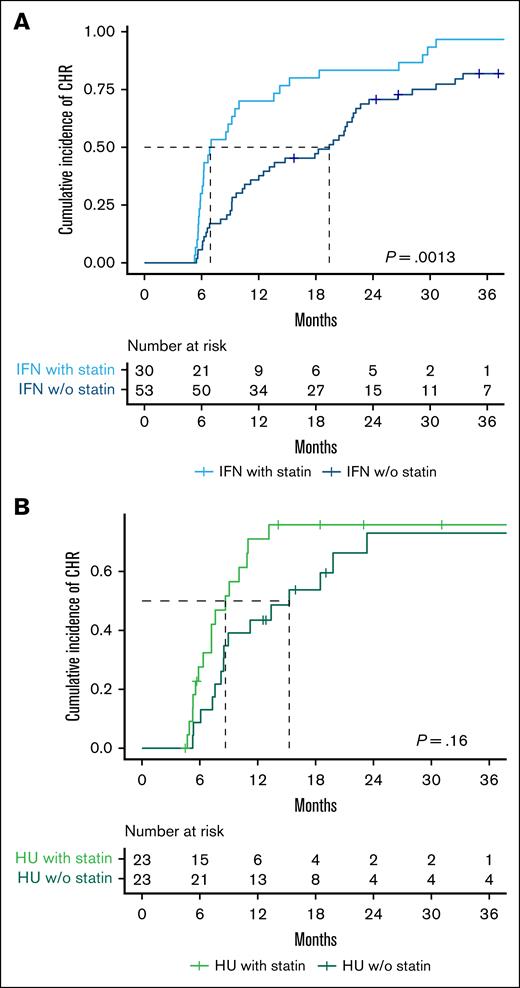

We further assessed the difference in cumulative CHR incidence based on cytoreductive treatment and statin use. The CHR was 83% in IFN-α2-treated non–statin users and 97% in IFN-α2-treated statin users, with a median time to CHR of 19 months and 7 months, respectively (P = .0013; Figure 2A). Statin use was significantly associated with achieving a CHR with a HR (95% CI) of 2.5 (1.5-3.9), P = .0004 (Figure 3). The CHR was 65% in HU-treated non–statin users and 70% in HU-treated statin users, with a median time to CHR of 15 months and 9 months, respectively (P = .16; Figure 2B). Contrarily, statin use was not associated with achieving a CHR among the HU-treated patients with a HR (95% CI) of 1.7 (0.9-3.6), P = .2 (Figure 3).

Statin use is associated with faster achievement of CHR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients but shows no clear benefit in HU-treated patients. Kaplan-Meier plot showing time to CHR stratified by cytoreductive treatment and statin use. (A) Patients treated with IFN-α2 (n = 83). The median time to CHR was 19 months for non–statin users and 7 months for statin users. (B) Patients treated with HU (n = 46). The median time to CHR was 15 months for non–statin users and 9 months for statin users. The log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative incidence of CHR. w/o, without.

Statin use is associated with faster achievement of CHR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients but shows no clear benefit in HU-treated patients. Kaplan-Meier plot showing time to CHR stratified by cytoreductive treatment and statin use. (A) Patients treated with IFN-α2 (n = 83). The median time to CHR was 19 months for non–statin users and 7 months for statin users. (B) Patients treated with HU (n = 46). The median time to CHR was 15 months for non–statin users and 9 months for statin users. The log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative incidence of CHR. w/o, without.

Statin use is significantly associated with CHR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients with MPN. Forest plot showing the HRs for CHR according to statin use. The multivariable-adjusted Cox regression was adjusted for age, sex, and smoking. w/o, without.

Statin use is significantly associated with CHR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients with MPN. Forest plot showing the HRs for CHR according to statin use. The multivariable-adjusted Cox regression was adjusted for age, sex, and smoking. w/o, without.

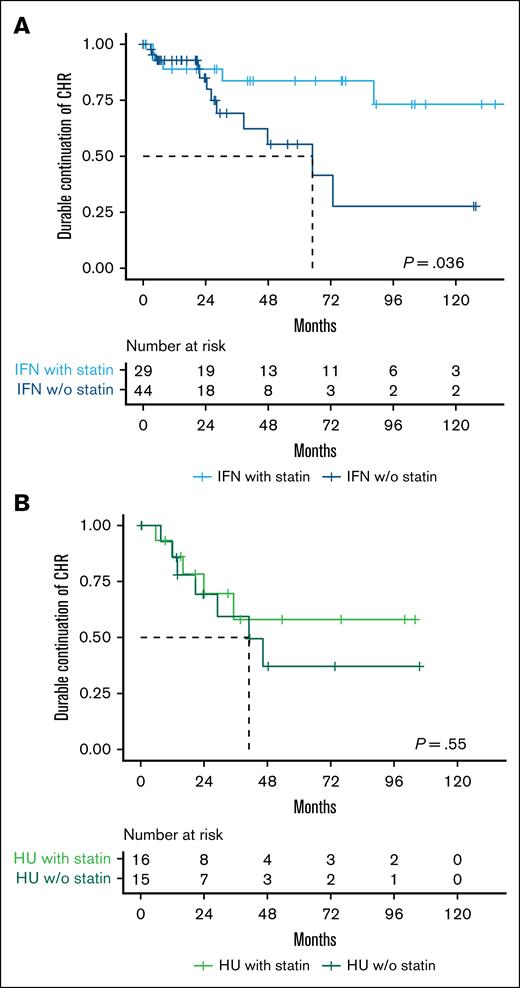

After achieving a CHR, 50% of IFN-α2-treated non–statin users and 66% of IFN-α2-treated statin users maintained CHR throughout the follow-up period (P = .04), whereas only 27% of HU-treated non–statin users and 44% of HU-treated statin users maintained CHR throughout the follow-up period (P = .8; supplemental Figure 1). When applying the definition of durable CHR, 73% of IFN-α2-treated non–statin users and 83% of IFN-α2-treated statin users maintained CHR throughout the follow-up period (P = .036) (Figure 4A), while 56% of HU-treated non–statin users and 69% of HU-treated statin users maintained CHR throughout the follow-up period (P = .55; Figure 4B).

Statin use is associated with a higher rate of sustained durable CHR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients with MPN. Kaplan-Meier plots showing time from initial CHR to loss of durable CHR (defined as loss of CHR across at least two consecutive clinic visits spanning ≥6 months), stratified by cytoreductive treatment and statin use. (A) Patients treated with IFN-α2 who achieved a CHR (n = 73). (B) Patients treated with HU who achieved a CHR (n = 31). w/o, without.

Statin use is associated with a higher rate of sustained durable CHR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients with MPN. Kaplan-Meier plots showing time from initial CHR to loss of durable CHR (defined as loss of CHR across at least two consecutive clinic visits spanning ≥6 months), stratified by cytoreductive treatment and statin use. (A) Patients treated with IFN-α2 who achieved a CHR (n = 73). (B) Patients treated with HU who achieved a CHR (n = 31). w/o, without.

The association between statin treatment intensity and CHR was evaluated. When considering statin treatment intensity independently, a dose-response relationship was evident for each increase in statin intensity among IFN-α2-treated statin users. For moderate intensity statin the HR (95% CI) was 2.3 (1.3-4.1), P = .005, and for high intensity statin the HR (95% CI) was 2.9 (1.4-5.8), P = .005 (Figure 5). A significant trend was observed, with increasing statin intensity with a HR (95% CI) of 1.4 (1.2-1.8), P = .0003. However, the same trend was not observed among HU-treated statin users with a HR (95% CI) of 1.3 (0.9-1.7), P = .1 (supplemental Figure 2).

Increasing statin intensity is associated with higher HRs for CHR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients with MPN. Forest plot showing HR for CHR according to statin treatment intensity among patients treated with IFN-α2. A dose-response relationship was observed, with moderate intensity statin use associated with an HR (95% CI) of 2.3 (1.3-4.1), P = .005 and high intensity statin use associated with an HR (95% CI) of 2.9 (1.4-5.8), P = .005. The multivariable-adjusted Cox regression was adjusted for age, sex, and smoking. W/o, without.

Increasing statin intensity is associated with higher HRs for CHR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients with MPN. Forest plot showing HR for CHR according to statin treatment intensity among patients treated with IFN-α2. A dose-response relationship was observed, with moderate intensity statin use associated with an HR (95% CI) of 2.3 (1.3-4.1), P = .005 and high intensity statin use associated with an HR (95% CI) of 2.9 (1.4-5.8), P = .005. The multivariable-adjusted Cox regression was adjusted for age, sex, and smoking. W/o, without.

To explore whether the association between statin use and CHR varied by disease subtype or mutation status, we conducted exploratory subgroup analyses within ET, PV, and JAK2 mutated patients treated with IFN-α2. Among patients with ET (n = 27), all patients, regardless of statin use, achieved a CHR, and no statistically significant difference in time to CHR was observed. In contrast, among patients with PV (n = 43), statin use was associated with both a higher probability of achieving CHR (frequency: 100% vs 77%) and a shorter time to response (median: 10 vs 23 months, P = .0036; supplemental Figure 3), with a HR (95% CI) of 4.6 (2.0-10.6), P = .0003. Similarly, in JAK2 mutated IFN-α2-treated patients (n = 63), statin use was associated with both a higher probability of achieving CHR (frequency: 100% vs 79%) and a shorter time to response (median: 7 vs 21 months, P = .00023; supplemental Figure 4), with a HR (95% CI) of 3.5 (1.9-6.4), P = .00005.

Differences in cytoreductive treatment according to statin use were compared. Among IFN-α2-treated patients, 45% of non–statin users received pretreatment with HU for <3 months, compared to 30% of statin users (P = .257). The mean HU dose per week was similar between groups, with non–statin users receiving 5600 mg and statin users receiving 5800 mg (P = .775). Both groups started IFN-α2 treatment at comparable doses, with non–statin users receiving a mean of 48.2 μg/wk and statin users receiving 48.8 μg/wk (P = .836). However, during follow-up, statin users received a significantly lower mean dose of 36.8 μg/wk compared to 51.6 μg/wk in non–statin users (P = .001). Sixteen of the 30 IFN-α2-treated statin users underwent dose reductions of IFN-α2. All 16 had sustained long-term CHR prior to dose reduction, including those whose dose reductions were influenced by manageable side effects, such as leukopenia (3 patients), fatigue (3 patients), stomatitis (1 patient), and shortness of breath (1 patient). The remaining dose reductions were due solely to sustained long-term CHR. Importantly, none of these dose adjustments were attributed to adverse events potentially related to statin use, such as musculoskeletal complaints or elevated liver enzymes (eg, ALAT). For HU-treated patients, no statistically significant differences in treatment parameters were observed between non–statin users and statin users. The mean starting dose of HU per week was 4680 mg in non–statin users and 4560 mg in statin users (P = .98). Similarly, the mean dose of HU per week during follow-up was 4300 mg in non–statin users and 4240 mg in statin users (P = .89).

JAK2-subgroup: the effect of statin on the molecular response

In supplemental Figure 5, the absolute JAK2 reduction is shown for all patients in the JAK2-subgroup, stratified by statin use. We assessed the difference in cumulative PMR incidence based on IFN-α2 treatment and statin use. Among non–statin users, 77% achieved a PMR, while 76% of statin users achieved a PMR. In both groups, 1 patient also achieved a complete molecular response. The median time to a PMR was 30 months for IFN-α2-treated non–statin users and 16 months for IFN-α2-treated statin users (P = .048; Figure 6). Statin use was significantly associated with achieving a PMR in the JAK2-subgroup by a HR (95% CI) of 2.6 (1.1-6.0), P = .029.

Statin use is associated with faster achievement of PMR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients. Kaplan-Meier plot showing time to PMR stratified by statin use. The median time to PMR was 30 months for non–statin users and 16 months for statin users. The log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative incidence of PMR. w/o, without.

Statin use is associated with faster achievement of PMR in pegylated IFN-α2–treated patients. Kaplan-Meier plot showing time to PMR stratified by statin use. The median time to PMR was 30 months for non–statin users and 16 months for statin users. The log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative incidence of PMR. w/o, without.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of statin use in combination with standard cytoreductive treatment on the hematological and molecular responses in patients with MPNs.

Statin users achieved CHR faster and more frequently compared to patients treated with IFN alone. Additionally, a larger proportion of statin users maintained CHR throughout the follow-up period. Furthermore, statin users were treated with lower doses of IFN-α2. The fact that statin users needed lower doses of cytoreductive treatment to obtain and maintain a hematological response suggests that statin treatment may enhance the effect of IFN-α2. The dose-response relationship observed in the trend analysis further supports this hypothesis. The significant trend indicated that increasing statin intensity was associated with improved outcomes in terms of CHR, reinforcing the potentially enhancing effect of a statin in patients being treated with IFN-α2. This was further substantiated by the analysis of the molecular response, where statin use was significantly associated with obtaining a PMR. The clinical benefit of molecular remission has not been fully clarified. However, a higher JAK2 allelic burden has been reported to be associated with an increased risk of thrombotic events and progression to MF.42,43 The latest data from the CONTINUATION-PV and MAJIC-PV studies indicate that patients who achieve a molecular response have better event-free survival compared to those who do not.44,45

A plausible biological explanation for statins enhancing the effect of IFN-α2 might be their anti-inflammatory properties.5-7 Studies in patients with hepatitis have shown that the effects of IFN are negatively affected by inflammation,46 and since patients with MPN have a systemic inflammatory load, this may interfere with IFN signaling. Therefore, by dampening the chronic inflammation in patients with MPN, statins might improve IFN signaling, enhancing the efficacy of IFN-α2. The fact that chronic inflammation may affect the treatment response in patients with MPN has been demonstrated in other studies as well. The COMBI I and II studies have shown that combination therapy with ruxolitinib, a highly potent anti-inflammatory drug, increases the efficacy and tolerability of IFN-α2 in patients with MPN.28,31-34 Furthermore, another study has shown that smoking, a potent inflammatory stimulus, may impair the IFN response in patients with MPN.47 In this context, our exploratory subgroup analyses provide preliminary support for this biological explanation. Among PV and JAK2 mutated patients, subgroups typically associated with a higher inflammatory burden, statin use was associated with a significantly higher probability of achieving CHR and a notably shorter time to response. By contrast, no difference was observed in ET patients, where all achieved CHR regardless of statin use, possibly reflecting a milder disease phenotype with lower inflammatory activity. Although these subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution due to limited sample size, the differential response by subtype raise a hypothesis-generating signal that the anti-inflammatory synergy between statins and IFN is more relevant in settings of higher baseline inflammation.

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective design and small cohort size. The assessments of JAK2 VAF were performed irregularly; patients with ≥2 measurements had between 2 and 26 measurements during the follow-up period. Furthermore, the time between measurements varied considerably, which limits the evaluation of the molecular response. Only 13 of the patients treated with HU had ≥2 JAK2 VAF measurements, so although it would be relevant to investigate whether the same response could be found among these patients, PMR was not analyzed due to insufficient data. Moreover, because LDL-C measurements are not routinely included in MPN follow-up, we were unable to assess whether the observed statin effect was mediated by LDL-C reduction or anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

Additionally, statin users differed from nonusers (Table 1) in several characteristics, including a higher proportion of former smokers, a higher prevalence of comorbidities (hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and thromboembolic events), and lower total cholesterol and LDL-C. The differences observed in the study might be affected by healthy user bias, where statin users may have better health-related behaviors, such as a greater willingness to improve health habits or better compliance to treatment. This could be reflected in the fact that a higher proportion of statin users were former smokers.

Our initial time-to-event analysis likely overestimated loss of CHR by counting any single blood cell deviation as an event, which may not reflect clinically meaningful loss of response. To address this, we performed a supplementary analysis defining durable CHR, providing a more reliable estimate of sustained hematological control and reducing the influence of transient fluctuations or dose adjustments. However, the retrospective design and variability in clinic visit intervals limit the precision of these assessments compared to controlled clinical trials. Furthermore, the durable CHR analysis included fewer events, increasing statistical uncertainty and potentially reducing power. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that statins could be beneficial in the treatment of patients with MPN, an observation that requires validation in prospective studies.

Our study has several important implications. The potential ability of statins to enhance the efficacy of IFN may provide considerable benefit to patients with MPN, especially as our data suggest that concomitant treatment with statins and IFN-α2 is associated with higher response rates and may allow for lower IFN-α2 dosing. If confirmed in prospective studies, this could lead to a more cost-effective and better-tolerated treatment approach, potentially reducing cumulative drug exposure and overall treatment burden. Furthermore, combining statins with IFN-α2 early in the disease course may delay the need for more intensive therapies and support long-term disease control. This approach aligns with the emerging treatment paradigm in MPNs, which increasingly focuses on achieving disease modification and potentially altering the natural course of the disease.48-50

In conclusion, statin use may increase the rate of hematological and molecular response in patients with MPN treated with IFN-α2. However, the impact of statins in HU-treated patients remains inconclusive. These findings highlight the need for further studies to clarify the potential role of statins in the treatment of patients with MPN.

Acknowledgments

C.E. was partly funded by the Laboratory Endowment Fund at Boston Children's Hospital. This work was funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation Clinical Accelerator program.

Authorship

Contribution: I.D.D., M.K.L., A.L.S., C.E., and H.C.H. conceived the study; I.D.D. collected data, wrote the article, made the tables and figures, and performed all the statistical analysis under supervision of M.K.L. and C.E.; and all authors contributed substantially to revision and interpretation and approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.C.H. reports research funding from Novartis and AOP Orphan. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Isabella Diana Davidsen, Department of Hematology, Zealand University Hospital, Vestermarksvej 9-11, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark; email: isaha@regionsjaelland.dk.

References

Author notes

Partly presented as a poster abstract at the 66th annual meeting and exposition of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 7 to 10 December 2024.

The data set cannot be shared publicly because of the European General Data Protection Regulation. If investigators would like to collaborate, please contact the corresponding author, Isabella Diana Davidsen (isaha@regionsjaelland.dk).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.