Key Points

SCI is progressive during clinical remission of iTTP.

Progressive SCI is associated with stroke and persistent cognitive impairment.

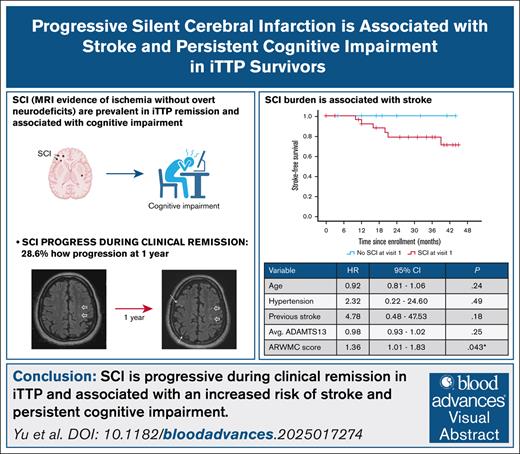

Visual Abstract

Survivors of immune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (iTTP) face an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease, including silent cerebral infarction (SCI), cognitive impairment, and stroke. The prospective Neurologic Sequelae of iTTP study evaluated the natural history of SCI (by brain magnetic resonance imaging) during clinical remission and its association with stroke risk and cognitive impairment, measured by the National Institutes of Health Toolbox cognition battery. SCI burden was quantified using the modified age-related white matter changes (ARWMC) score. Among 42 patients who completed the baseline study visit, 28 completed a second assessment at a median interval of 12.5 months. New or progressive SCI were observed in 8 of 28 patients (28.6%), with the median ARWMC score increasing from 4 to 5 (P = .002). SCI progression was associated with a higher baseline ARWMC score (median, 7 vs 1; P = .011) but not with age, hypertension, diabetes, or average remission ADAMTS13 activity. Over a median follow-up of 32 months, 6 of 42 participants (14.3%) developed stroke, with significantly higher stroke risk among those with a higher baseline ARWMC score (hazard ratio, 1.36; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.83; P = .043). Cognitive function significantly improved in patients without SCI progression but not in those with progressive SCI. In summary, SCI is progressive during clinical remission in iTTP and associated with an increased risk of stroke and persistent cognitive impairment. SCI burden and progression may serve as shorter-term end points for clinical trials aimed at mitigating stroke risk and improving cognitive outcomes after iTTP.

Introduction

Immune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (iTTP) is a rare, life-threatening thrombotic microangiopathy caused by severe ADAMTS13 deficiency, leading to systemic microvascular thrombosis due to accumulation of ultralarge von Willebrand factor (VWF) multimers.1 Rapid diagnosis and effective treatment have reduced mortality of acute episodes from >90% to <5%.2-4 In addition to the risk of iTTP relapse, survivors of iTTP face significant long-term health challenges, including higher rates of chronic morbidities such as autoimmune diseases,5 hypertension,6 cardiovascular disease,6-9 and shortened survival, which is largely attributable to the high rates of cardiovascular disease. Neurologic complications are a particular concern with a nearly fivefold increased risk of stroke compared with the general population, which is also associated with reduced ADAMTS13 during remission,10,11 and most survivors of iTTP exhibit cognitive impairment, limiting daily functioning and impairing quality of life.12-15

In addition to the increased risk of stroke, up to half of survivors of iTTP evaluated during clinical remission demonstrate silent cerebral infarction (SCI), defined as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-detected brain ischemia without overt focal neurologic deficits. SCI occurs at a rate of 5% to 10% in the general population and increase with age.16,17 Originally considered imaging artefacts, SCIs are now recognized on a spectrum of cerebrovascular injury that includes stroke, and SCI is associated with cognitive impairment and risk of stroke in both the general population and conditions such as sickle cell disease.12,18 Our previous work has shown that >50% of survivors of iTTP experience SCI during remission, which is strongly associated with major and minor cognitive impairment.12 However, the epidemiology and natural history of SCI in iTTP remain poorly understood. Specifically, it is unknown whether SCI are merely the sequelae of ischemia during acute iTTP, or they progress during clinical remission of iTTP. Whether SCI (and SCI progression) is a predictor of overt stroke in iTTP is also unknown. This study leverages the prospective Neurologic Sequelae of iTTP cohort to test the hypothesis that SCI is progressive during clinical remission of iTTP, identify risk factors of SCI progression, and evaluate the association of SCI with incident stroke in survivors of iTTP, with the goal of identifying the optimal timing and therapeutic targets to improve neurologic outcomes in iTTP.

Methods

Study design and participants

The Neurologic Sequelae of iTTP study12 prospectively enrolled adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with a confirmed diagnosis of iTTP from the hematology clinics at Johns Hopkins University between September 2020 and December 2024. The diagnosis of iTTP was made based on ADAMTS13 activity of <10% with an anti-ADAMTS13 antibody or inhibitor during an acute episode characterized by thrombocytopenia (platelet count of <150 × 109/L) and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (hemoglobin of <10 g/dL with schistocytes on the blood smear). Patients were eligible for enrollment if they were in clinical remission, defined as a platelet count of >150 × 109/L and lactate dehydrogenase of <1.5 times the upper limit of normal for at least 30 days after cessation of plasma exchange or anti-VWF therapy.9 Patients with neurodegenerative conditions or conditions that confound neurologic evaluation were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Johns Hopkins University. Clinical and demographic data were obtained from electronic medical records and confirmed through patient interviews. Participants underwent annual study visits during their clinical remission periods, including but not limited to (1) screening for acute stroke with National Institutions of Health (NIH) stroke scale, (2) brain MRI to evaluate for SCI, and (3) the NIH ToolBox cognition battery. Assessments at the first study visit were used to determine baseline rates of SCI and cognitive impairment, as reported previously.12 The goal of the subsequent annual assessments is to evaluate the progression of SCI and functional deficits. Participants were followed up until death or last clinical contact.

Study procedures

Brain MRI and image analysis

Brain MRI was performed using a Siemens 3T Prisma Fit scanner, as previously described.12 In summary, the imaging protocol included sagittal 3-dimensional T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo, 3-dimensional fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, axial diffusion-weighted imaging, susceptibility-weighted imaging, and T2-weighted sequences. MRIs were reviewed by a team of board-certified neuroradiologists who were blinded to clinical, laboratory, and cognitive assessments. SCI was defined as an ischemic (infarct-like) lesion manifesting as a focus of T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensity and with no corresponding neurologic deficit (by clinical neurologic examination and the NIH stroke scale). Additionally, SCI burden was quantified using the modified age-related white matter changes (ARWMC) scale.19,20 Lesions were scored for predefined brain regions (frontal, parieto-occipital, temporal, infratentorial/cerebellum, and basal ganglia) on both hemispheres. Each region receives a score between 0 and 3, and total scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater lesion burden. Patients without SCI have an ARWMC score of 0.

Cognitive assessment

Cognitive function was evaluated using the NIH Toolbox cognition battery, as previously described.12 To summarize, this battery is a validated tool that assesses multiple cognitive domains including executive function, processing speed, episodic memory, working memory, and language.21 Results were reported as age-, sex-, and education-adjusted T-scores (normative mean of 50 with standard deviation [SD] of 10). Definitions of mild and major cognitive impairment followed Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)-5 criteria, with mild impairment defined as T-scores of 1 or 2 SDs below the mean, and major impairment as scores of >2 SDs below the mean on at least 1 test, respectively.22 The NIH Toolbox cognition battery shows strong test-retest reliability, especially in its composite scores, making it appropriate for longitudinal research. However, some individual tests may be subject to practice effects, with certain measures showing small yet statistically significant improvements over time.21,23

BDI-II

The Beck depression inventory II (BDI-II) is an extensively validated, self-administered depression screening tool.24 It includes 21 items, each scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms.

Clinical data management

We extracted clinical data from the medical record including details of iTTP diagnosis and treatment and the presence of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity (body mass index of >30 kg/m2), hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, smoking status, chronic kidney disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other autoimmune conditions. Additional data included a history of stroke and laboratory parameters, such as ADAMTS13 activity levels measured every 3 months during clinical remission. Any acute stroke occurring after enrollment was recorded as an outcome. Incident stroke was defined as a documented new neurologic deficit(s) with a corresponding ischemic lesion(s) on MRI of the brain. The determination of stroke was restricted to patients who presented with focal neurologic symptoms lasting >24 hours (and excluding those with transient focal symptoms), consistent with the World Health Organization definition of stroke. The requirement of a brain MRI showing a new acute ischemic lesion (increased diffusion-weighted imaging signal or increased signal on T2-weighted image) compared with baseline MRI was added to exclude old stroke or ischemic lesions.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), and categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages. We compared the characteristics of participants who completed visit 2 versus those who have not completed visit 2 to evaluate for selection bias. The proportion of participants with new or progressive SCI lesions (increase in ARWMC score by ≥1) was calculated, and the change in ARWMC scores between baseline and follow-up MRI was compared using the paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. We first performed univariate analysis comparing participants with and without new or progressive SCI lesions using the χ2 test for categorical covariates and the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Next, multivariable logistic regression models were developed to identify risk factors for SCI progression at 1 year including age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, previous stroke, SCI at baseline (visit 1), and average remission ADAMTS13 levels as covariates. The rate of incident stroke was calculated, and we performed univariate analysis to evaluate differences by incident stroke status using the χ2 test for categorical covariates and the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Next, Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate risk factors for incident stroke with separate models including baseline SCI at visit 1 and changes in SCI (both as a dichotomous variable [yes/no] and as the continuous variable of change in ARWMC scores). Other covariates for these models were selected on biological plausibility and known or suspected associations with SCI and stroke, and time of enrollment (visit 1) was considered time 0. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed, and Martingale and deviance residuals were used to assess model assumptions and the effect of outlier cases. Finally, separate Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to compare stroke-free survival in participants with and without baseline SCI at visit 1 and SCI progression at visit 2. Changes in cognition test scores between visits were compared using paired t tests. Subgroup analyses were conducted for participants with and without progressive SCI based on the hypothesis that SCI progression would be associated with persistence or progression of cognitive deficits. P < .05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 17.0.

Results

Patient characteristics

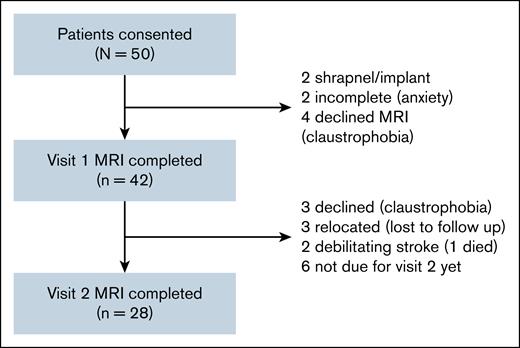

Of 50 patients screened for the study, 42 patients completed the first visit including MRI, and 28 completed the second visit between September 2020 and December 2024. Of the remaining 14 patients, 3 patients declined subsequent MRI due to claustrophobia, 3 were lost to follow-up due to relocation, 2 had debilitating strokes (1 of which was fatal), and 6 patients were not yet due for their second visit at the data cutoff time (Figure 1). The median age was 47.5 years at visit 1 and 48 years at visit 2, with most participants being female (78.6%) and identifying as Black (71.4%). The median time since iTTP diagnosis was 41 (IQR, 7.5-89.5) months, with a median of 2 iTTP (IQR, 1-4) episodes. Comorbid conditions included hypertension in 35.7% patients, diabetes in 16.7%, and a history of stroke during an acute iTTP episode in 23.8%. At baseline evaluation, the median time between MRI assessments was 12.5 months, and the average ADAMTS13 activity (average of 4 values evaluated quarterly) during remission between visits 1 and 2 was 73.4% (IQR, 58.2-95.7). Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable . | Completed V1 (n = 42)∗ . | Completed V2 (n = 28)∗ . | Did not complete V2 (n = 14) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 47.5 (34.25-54.25) | 48 (35-53) | 44 (29-57) |

| Female sex | 78.6% | 75% | 85.7% |

| Black race | 71.4% | 78.6% | 57.1% |

| Time from iTTP diagnosis, median (IQR), mo | 41 (7.5-89.5) | 50 (6-109) | 39 (13-76) |

| Hypertension | 35.7% | 39.3% | 28.6% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16.7% | 21.4% | 7.1% |

| Stroke during iTTP | 23.8% | 28.6% | 14.3% |

| Any SCI at V1 | 69% (29/42) | 68% (19/28) | 71.4% (10/14) |

| ARWMC score (for SCI) at V1, median (IQR) | 4 (0-7) | 3 (0-7) | 4 (0-7) |

| Time between MRI1 and MRI2, median (range), mo | — | 12.5 (12-14) | — |

| Average ADAMTS13 activity between V1 and V2, median (IQR) | — | 73.4 (58.2-95.7) | — |

| Variable . | Completed V1 (n = 42)∗ . | Completed V2 (n = 28)∗ . | Did not complete V2 (n = 14) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 47.5 (34.25-54.25) | 48 (35-53) | 44 (29-57) |

| Female sex | 78.6% | 75% | 85.7% |

| Black race | 71.4% | 78.6% | 57.1% |

| Time from iTTP diagnosis, median (IQR), mo | 41 (7.5-89.5) | 50 (6-109) | 39 (13-76) |

| Hypertension | 35.7% | 39.3% | 28.6% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16.7% | 21.4% | 7.1% |

| Stroke during iTTP | 23.8% | 28.6% | 14.3% |

| Any SCI at V1 | 69% (29/42) | 68% (19/28) | 71.4% (10/14) |

| ARWMC score (for SCI) at V1, median (IQR) | 4 (0-7) | 3 (0-7) | 4 (0-7) |

| Time between MRI1 and MRI2, median (range), mo | — | 12.5 (12-14) | — |

| Average ADAMTS13 activity between V1 and V2, median (IQR) | — | 73.4 (58.2-95.7) | — |

MRI1, MRI at V1; MRI2, MRI at V2; V1, visit 1; V2, visit 2.

The group that completed V2 is a subset of the group that completed V1.

Progression of SCI during clinical remission

Any SCI was present in 29 of 42 (69%) enrolled patients and 19 of 28 (68%) who completed visit 2. Among these, new SCI or an increase in SCI burden as measured by ARWMC score was observed in 8 of 28 (28.6%) participants during clinical remission, all of whom had some SCI lesions at visit 1, indicating an increase in the SCI burden in those with known SCI rather than increased prevalence.

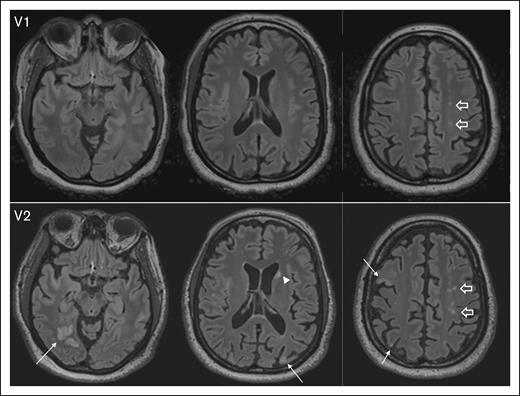

The median ARWMC score significantly increased from 3 (IQR, 0-7) at baseline (visit 1) to 4 (IQR, 1-7) at visit 2 (P = .002), suggesting ongoing cerebrovascular injury despite the absence of acute iTTP episodes. Representative MRI images illustrate the development of new lesions and the enlargement of existing SCI from visit 1 to visit 2 (Figure 2).

Representative images depicting progression of SCI burden between V1 and visit 2 V2, with brain MRI completed 12 months apart. At V1, axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images show several punctate foci of hyperintensity in the centrum semiovale (block arrows). At V2, there is interval development of multifocal chronic cortical infarcts; for example, in the right occipital, right and left parietal lobes, and right middle frontal gyrus (arrows), as well as an ischemic focus in the left caudate head (arrowhead). In addition, multifocal FLAIR hyperintense white matter lesions in the centrum semiovale bilaterally have increased in number and conspicuity (block arrows). V1, visit 1; V2, visit 2.

Representative images depicting progression of SCI burden between V1 and visit 2 V2, with brain MRI completed 12 months apart. At V1, axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images show several punctate foci of hyperintensity in the centrum semiovale (block arrows). At V2, there is interval development of multifocal chronic cortical infarcts; for example, in the right occipital, right and left parietal lobes, and right middle frontal gyrus (arrows), as well as an ischemic focus in the left caudate head (arrowhead). In addition, multifocal FLAIR hyperintense white matter lesions in the centrum semiovale bilaterally have increased in number and conspicuity (block arrows). V1, visit 1; V2, visit 2.

The baseline ARWMC score at visit 1 was significantly higher in patients with SCI progression (median 7 vs 1, P = .011) on univariate testing (Table 2). However, other demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, sex, race, comorbidities, and average ADAMTS13 activity between assessments did not significantly differ between those with and without SCI progression (Table 2). To evaluate risk factors associated with SCI progression, we performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis. Baseline ARWMC score at visit 1 (odds ratio [OR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89-1.67) was not significantly associated with SCI progression after adjusting for age (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.90-1.09), hypertension (OR, 8.80; 95% CI, 0.62-124.13), previous stroke during iTTP (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.11-9.84), and average ADAMTS13 activity between visit 1 and 2 assessments (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.98-1.17).

Characteristics of participants with and without new or progressive SCI, single variable

| Variable . | No new SCI (n = 20) . | New SCI (n = 8) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 45 (30-54.5) | 49 (48-51) | .165 |

| Female sex | 75% | 75% | 1.000 |

| Black race | 75% | 87.5% | .202 |

| Time from iTTP diagnosis, median (IQR), mo | 68 (6.5-109) | 14 (2-168) | .438 |

| Hypertension | 30% | 62.5% | .112 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15% | 37.5% | .190 |

| Stroke during iTTP | 20% | 50% | .112 |

| ARWMC score at V1, median (IQR) | 1 (0-6) | 7 (4.25-9) | .011∗ |

| Average ADAMTS13 activity between V1 and V2, median (IQR) | 72 (50.5-94.0) | 95.5 (70.7-100.0) | .116 |

| Variable . | No new SCI (n = 20) . | New SCI (n = 8) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 45 (30-54.5) | 49 (48-51) | .165 |

| Female sex | 75% | 75% | 1.000 |

| Black race | 75% | 87.5% | .202 |

| Time from iTTP diagnosis, median (IQR), mo | 68 (6.5-109) | 14 (2-168) | .438 |

| Hypertension | 30% | 62.5% | .112 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15% | 37.5% | .190 |

| Stroke during iTTP | 20% | 50% | .112 |

| ARWMC score at V1, median (IQR) | 1 (0-6) | 7 (4.25-9) | .011∗ |

| Average ADAMTS13 activity between V1 and V2, median (IQR) | 72 (50.5-94.0) | 95.5 (70.7-100.0) | .116 |

V1, visit 1; V2, visit 2.

∗indicates differences that are significant with P < 0.05

SCI is associated with increased stroke risk

Over a median follow-up of 32 months (IQR, 16-43) since baseline evaluation, 6 of 42 (14.3%) participants experienced a stroke. Of these, 3 completed visit 2 MRI. Of the other 3, 1 was unable to complete it due to a debilitating stroke, 1 was lost to follow-up after the stroke, and 1 declined repeat MRI due to claustrophobia.

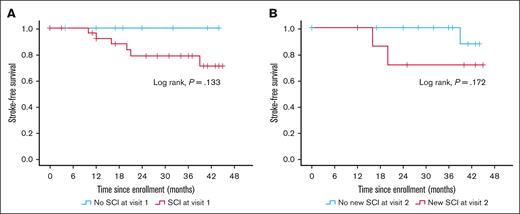

We assessed the association of incident stroke both with SCI at baseline (visit 1) and progression of SCI over 1 year (between visits 1 and 2). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that stroke-free survival did not significantly differ between patients with and without SCI at baseline or based on SCI progression status, likely due to small numbers (Figure 3). However, when SCI burden was analyzed quantitatively using ARWMC scores in the Cox regression model, a higher ARWMC score at baseline was significantly associated with stroke risk (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.01-1.83; P = .043) adjusted for age (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.81-1.06; P = .244], hypertension (HR, 2.32; 95% CI, 0.22-24.60; P = .486), previous stroke (HR, 4.78; 95% CI, 0.48-47.53; P = .182), and average ADAMTS13 activity (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93-1.02; P = .249; Table 3, model 1).

Association between SCI and risk of stroke. Kaplan-Meier curve showing incident stroke-free survival in patients with and without SCI at baseline (A), and patients with and without SCI progression between visits 1 and 2, ∼12 months apart (B).

Association between SCI and risk of stroke. Kaplan-Meier curve showing incident stroke-free survival in patients with and without SCI at baseline (A), and patients with and without SCI progression between visits 1 and 2, ∼12 months apart (B).

Cox regression models evaluating association of SCI burden (measured as ARWMC score) and change in SCI burden with incident stroke

| Variable . | Model 1 including ARWMC at baseline (n = 42) . | Model 2 including change in ARWMC (n = 28) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age | 0.92 | 0.81-1.06 | .24 | 0.974 | 0.76-1.25 | .835 |

| Hypertension | 2.32 | 0.22-24.60 | .49 | 2.06 | 0.05-88.50 | .707 |

| Previous stroke | 4.78 | 0.48-47.53 | .18 | 3.03 | 0.20-46.40 | .427 |

| Average ADAMTS13 | 0.98 | 0.93-1.02 | .25 | 0.98 | 0.90-1.06 | .606 |

| ARWMC score at baseline | 1.36 | 1.01-1.83 | .043 | 1.18 | 0.72-1.93 | .505 |

| Change in ARWMC score | — | — | — | 1.21 | 0.84-1.75 | .315 |

| Variable . | Model 1 including ARWMC at baseline (n = 42) . | Model 2 including change in ARWMC (n = 28) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | HR . | 95% CI . | P value . | |

| Age | 0.92 | 0.81-1.06 | .24 | 0.974 | 0.76-1.25 | .835 |

| Hypertension | 2.32 | 0.22-24.60 | .49 | 2.06 | 0.05-88.50 | .707 |

| Previous stroke | 4.78 | 0.48-47.53 | .18 | 3.03 | 0.20-46.40 | .427 |

| Average ADAMTS13 | 0.98 | 0.93-1.02 | .25 | 0.98 | 0.90-1.06 | .606 |

| ARWMC score at baseline | 1.36 | 1.01-1.83 | .043 | 1.18 | 0.72-1.93 | .505 |

| Change in ARWMC score | — | — | — | 1.21 | 0.84-1.75 | .315 |

Although increase in ARWMC score over 1 year was associated with a higher stroke risk in a Cox regression model when adjusted for age only (HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.02-1.84; P = .036), this association was no longer significant after adjusting for additional vascular and hematologic risk factors (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.89-1.78; P = .198), including hypertension, average ADAMTS13 activity, ARWMC score at visit 1, and previous stroke (Table 3, model 2).

Changes in cognitive function and depression outcomes

Scores on individual cognitive function tests and composite scores on the NIH ToolBox cognition battery did not significantly change at 1-year reevaluation for the entire cohort. When we separately examined patients with or without SCI progression, we found that patients who did not have an increase in SCI burden had numerical improvements in nearly all tests/domains and composite scores, and these differences were statistically significant for the fluid cognition composite and the total cognition composite as well as 2 individual tests (flanker inhibitory control, and attention and dimensional change card sort test). In contrast, there were no statistically significant improvements in cognition scores among patients who demonstrated an increase in SCI burden between the 2 assessments a year apart (Table 4).

NIH ToolBox cognition battery scores for patients with and without SCI progression

| Test . | No SCI progression (n = 20) . | SCI progression (n = 8) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-score at visit 1, median (IQR) . | T-score at visit 2, median (IQR) . | P value . | T-score at visit 1, median (IQR) . | T-score at visit 2, median (IQR) . | P value . | |

| Picture vocabulary | 51 (45, 59) | 52.5 (43.5, 60.75) | .548 | 57 (51.5, 63) | 55.5 (45.75, 58.75) | .624 |

| Oral reading recognition | 55 (50, 59) | 51 (47, 62.25) | .835 | 56 (42.5,68.7) | 53.3 (48.25, 64.75) | .723 |

| List sorting working memory | 48 (45, 53) | 52 (45.5, 59.25) | .116 | 53.5 (51.25, 58) | 51 (38.5, 62) | .233 |

| Picture sequence memory | 52 (42, 59) | 50.5 (43, 59.25) | .938 | 56.5 (51, 60.75) | 54.5 (47.75, 59.5) | .279 |

| Flanker inhibitory control and attention | 43 (36, 46) | 46.5 (39, 59.25) | .010 | 46.5 (38.25, 57.75) | 43 (34.75, 58.75) | .865 |

| Dimensional change cart sort test | 44 (34, 60) | 52 (45.75, 66.25) | .016 | 55.5 (48.25, 68.25) | 56.5 (51.5, 63.5) | .833 |

| Pattern recognition | 60 (43, 68) | 56 (38.75, 71.5) | .637 | 56.5 (42.75, 72.75) | 67 (40, 79) | .672 |

| Fluid cognition composite | 51 (37, 60) | 52.5 (38.25, 70.75) | .048 | 60.5 (47.5, 65.5) | 55.5 (41.25, 71.75) | .438 |

| Crystalized cognition composite | 52.5 (43.5, 60.75) | 53 (44.5, 63) | .575 | 60 (47, 65.5) | 55.5 (48, 62.75) | .686 |

| Total cognition composite | 55 (40, 60) | 57 (39.5, 64.75) | .023 | 55 (53, 70.25) | 56 (45, 74) | .397 |

| Test . | No SCI progression (n = 20) . | SCI progression (n = 8) . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-score at visit 1, median (IQR) . | T-score at visit 2, median (IQR) . | P value . | T-score at visit 1, median (IQR) . | T-score at visit 2, median (IQR) . | P value . | |

| Picture vocabulary | 51 (45, 59) | 52.5 (43.5, 60.75) | .548 | 57 (51.5, 63) | 55.5 (45.75, 58.75) | .624 |

| Oral reading recognition | 55 (50, 59) | 51 (47, 62.25) | .835 | 56 (42.5,68.7) | 53.3 (48.25, 64.75) | .723 |

| List sorting working memory | 48 (45, 53) | 52 (45.5, 59.25) | .116 | 53.5 (51.25, 58) | 51 (38.5, 62) | .233 |

| Picture sequence memory | 52 (42, 59) | 50.5 (43, 59.25) | .938 | 56.5 (51, 60.75) | 54.5 (47.75, 59.5) | .279 |

| Flanker inhibitory control and attention | 43 (36, 46) | 46.5 (39, 59.25) | .010 | 46.5 (38.25, 57.75) | 43 (34.75, 58.75) | .865 |

| Dimensional change cart sort test | 44 (34, 60) | 52 (45.75, 66.25) | .016 | 55.5 (48.25, 68.25) | 56.5 (51.5, 63.5) | .833 |

| Pattern recognition | 60 (43, 68) | 56 (38.75, 71.5) | .637 | 56.5 (42.75, 72.75) | 67 (40, 79) | .672 |

| Fluid cognition composite | 51 (37, 60) | 52.5 (38.25, 70.75) | .048 | 60.5 (47.5, 65.5) | 55.5 (41.25, 71.75) | .438 |

| Crystalized cognition composite | 52.5 (43.5, 60.75) | 53 (44.5, 63) | .575 | 60 (47, 65.5) | 55.5 (48, 62.75) | .686 |

| Total cognition composite | 55 (40, 60) | 57 (39.5, 64.75) | .023 | 55 (53, 70.25) | 56 (45, 74) | .397 |

Median scores for depressive symptoms on the BDI-II changed from 29 (IQR, 27-39.75) at visit 1, to 30 (IQR, 26.5-36.0) at visit 2 (P = .403 by paired-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test) for the overall cohort. BDI-II scores at visits 1 and 2 were not significantly different in patients who demonstrated SCI progression (29 [IQR, 29-46] vs 32 [IQR, 21-44], P = .345) or those without SCI progression (29 [IQR, 27-39.75] vs 30 [IQR, 26.5-36], P = .694).

Discussion

iTTP is increasingly recognized as a chronic stroke syndrome characterized by persistent neurovascular morbidity, including a high burden of stroke, SCI, and cognitive impairment.6,11,25 This is the first study to demonstrate that SCI is progressive during clinical remission of iTTP in the absence of intercurrent episodes in a rigorously conducted prospective study. We also found that cognitive function in several domains improved over a year in patients who did not have SCI progression, whereas patients with progressive SCI burden had no improvement in cognitive function over the same period. These findings suggest that intervening on modifiable risk factors for cerebrovascular disease during clinical remission may mitigate long-term neurologic deterioration and potentially facilitate recovery of cognitive function in this high-risk population.

SCI burden (measured by the ARWMC) was associated with increased risk of stroke during clinical remission even after adjusting for other risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and previous stroke. Although new or progressive SCI over 1 year was associated with shorter stroke-free survival, this association was not seen after adjusting for other risk factors, which may be due to the limited sample size in this analysis (only 3 stroke events in 28 patients). As this cohort continues to accrue follow-up data, we will reexamine the risk factors for stroke with additional patient-years of observation. Interestingly, average remission ADAMTS13 activity was not associated with either SCI progression or stroke risk. This contrasts with previous studies in which we found that reduced ADAMTS13 activity during remission (average ADAMTS13 activity below the lower limit of normal) was associated with stroke in survivors of iTTP.9-11 The most likely explanation for this discrepancy is that the previous retrospective study reported on an iTTP cohort with most of the patient-years of follow-up in the era before routine use of rituximab to treat ADAMTS13 deficiency in clinical remission. Since 2017, we have increasingly used preemptive rituximab to maintain higher remission ADAMTS13 activity (at least >20%) to prevent clinical relapse.4,26 Driven by recent observations that lower ADAMTS13 activity is associated with stroke and other vascular events in both iTTP and other populations,9-11 our practice has shifted toward maintaining even higher ADAMTS13 activity (>50%) when feasible (with regard to insurance coverage for rituximab). This makes it difficult to examine the impact of lower ADAMTS13 levels on SCI progression in the current cohort and this will need to be studied in cohorts at other centers. However, the presence of SCI progression despite adequate ADAMTS13 levels in the period between assessments suggests that factors beyond ADAMTS13 deficiency also contribute to cerebrovascular disease in iTTP. Additional research is needed to identify targetable mechanisms to mitigate cerebrovascular disease in this high-risk population.

Several studies have longitudinally assessed cognitive function in survivors of iTTP, yet growing evidence suggests that cognitive impairment is a significant long-term consequence of the disease.14,25,27-29 Previous research has demonstrated that survivors of iTTP exhibit persistent deficits in executive function, memory, and processing speed, which, in some cases, worsen over time.12,14,25 Our study builds upon these findings and provides mechanistic insight by demonstrating that cognitive impairment is associated with SCI12 and that the trajectory of cognitive function in survivors of iTTP is closely linked to SCI progression. We observed that patients without SCI progression showed stability or measurable improvements in cognitive performance over 1 year, whereas those with progressive SCI exhibited persistent cognitive deficits with no evidence of improvement. Our cohort included a small number (n = 8) of individuals with progressive SCI, and we were likely underpowered to detect small differences; validation in larger cohorts is needed. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that ongoing cerebrovascular injury may contribute to persistent (or worsening) cognitive dysfunction in survivors of iTTP, and SCI progression may be an early marker of long-term cognitive decline, reinforcing the need for close monitoring and early intervention.

We have previously shown that SCI is highly prevalent in survivors of iTTP, occurring much earlier in life and at rates much higher than expected in the general population, a finding that is reiterated in this report. Several mechanisms may contribute to progressive SCI and cerebrovascular disease in survivors of iTTP. Traditional vascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia that are common in iTTP cohorts likely exacerbate small-vessel damage, leading to progressive SCI and stroke risk.6-8,30 This analysis did not show an association between ADAMTS13 levels in the year between the first and second MRI, likely because there were few patients with persistent moderate or severe ADAMTS13 deficiency in this cohort. However, our previous studies have established that average ADAMTS13 below the lower limit of normal is associated with stroke, and this premise is further supported by the high rate of stroke in congenital TTP cohorts, and the association of ADAMTS13 and cerebrovascular disease in the general population. Thus, targeting normal (or close to normal) ADAMTS13 activity is reasonable. Health disparities also play a role, because iTTP disproportionately affects Black patients, a population with a higher burden of cardiovascular disease and systemic health care inequities.31,32 Chronic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, even in clinical remission, may drive ongoing vascular injury by promoting microvascular damage33-35 and impairing blood-brain barrier integrity.36,37 Future research should evaluate whether a combination of traditional vascular risk management, anti-inflammatory strategies, and endothelial-protective therapies can mitigate long-term neurologic outcomes in survivors of iTTP.

The limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size and single-year MRI follow-up, which may have curbed our ability to detect all relevant risk factors for SCI progression and stroke. Our iTTP cohort with a preponderance of (self-identified) Black individuals with high prevalence rates of traditional vascular risk factors, which may affect risk of SCI and stroke, may not be representative of iTTP cohorts everywhere. Additional longitudinal follow-up is ongoing, and a larger multicenter study has been initiated to confirm the generalizability of our findings and identify additional predictors of neurovascular disease in survivors of iTTP. Much larger studies are also needed to establish the natural history of cognitive impairment in iTTP, and the relationship with SCI progression and burden. The advancement in treatments with VWF-targeted therapies such as caplacizumab,38 which is increasingly used during acute iTTP episodes, also introduced variability in the management of iTTP during the extended study period. We cannot yet determine whether baseline SCI burden is influenced by caplacizumab. Future studies will investigate whether these therapies modify long-term vascular risks in survivors of iTTP.

In conclusion, SCI in patients with iTTP is neither silent nor innocuous. We have demonstrated that SCI progresses during iTTP remission, even in the absence of acute iTTP episodes. Progressive SCI is associated with increased stroke risk and persistent cognitive impairment, underscoring the long-term neurologic burden faced by survivors of iTTP. Importantly, our findings suggest that SCI burden and SCI progression may serve as objective and clinically relevant shorter-term end points for clinical trials aimed at reducing stroke risk and mitigating cognitive decline in this population. Given the complex interplay of vascular, inflammatory, and hematologic factors in iTTP, future research will focus on identifying modifiable risk factors and evaluating targeted interventions to preserve neurologic function and improve outcomes in survivors of iTTP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant R00HL172303 and an American Society of Hematology scholar award (S.C.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.C. designed the research, and performed and interpreted the analyses; J. Yu conducted part of the study assessments and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; J.M. and J.B. collected and analyzed parts of the data and critically reviewed the manuscript; G.F.G., S.M., A.M.P., M.B.S., P.K., J. Yui, R.P.N., and R.A.B. assisted with patient recruitment and critically reviewed the manuscript; D.D.L. led the neuroradiology team, designed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences, established MRI protocols, interpreted all study MRIs including imaging analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.C. served on advisory boards for Takeda, Sanofi, Alexion, Novartis, Star Pharmaceuticals, and Sobi; provided consulting services to Rallybio and Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceuticals; served on study steering committees for Sanofi, Takeda, and Sobi; and received authorship royalties from UpToDate. A.M.P. served on an advisory board for BioMarin; and received authorship royalties from UpToDate. G.F.G. served on advisory boards for Alexion and Apellis Pharmaceuticals; and received authorship honorarium from the Merck Manual. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Shruti Chaturvedi, Hematology and Oncology, Johns Hopkins University, 720 Rutland Ave, Ross Research Building, Room 1025, Baltimore, MD 21205; email: schatur3@jhmi.edu.

References

Author notes

Data and research materials made available for public access will be shared through the Johns Hopkins Research Data Repository (https://archive.data.jhu.edu/).

Original deidentified data are available on request from the corresponding author, Shruti Chaturvedi (schatur3@jhmi.edu); all requests for data will be reviewed for feasibility and priority.