Key Points

With the rise of ECMO use in adults with SCD, understanding important clinical outcomes and their association with mortality are essential.

Male sex, increased age, eCPR support, elevated lactate, and pre-ECLS arrest were strongest indicators of mortality on VA ECMO.

Visual Abstract

The utility of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support for adult patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) remains poorly understood. We aimed to characterize a cohort of adult individuals with SCD in the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry who underwent venoarterial (VA) or venovenous (VV) ECMO treatment, assess clinical outcomes, and determine predictors of mortality. This multicenter, retrospective study evaluated in-hospital mortality and clinical outcomes such as bleeding and thrombotic events (BTEs) of adult patients in the ELSO registry with SCD–associated International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revision, Clinical Modification codes. Post hoc multivariable logistic regression model was developed assessing predictors of mortality. Of 206 included patients, 126 and 80 received cannulation for VA ECMO or VV ECMO, respectively. Eighty-three patients (40.3%) were discharged alive; in-hospital survival was 25.5% and 61.1% for VA and VV ECMO, respectively (P < .001). BTEs were common during VA (45.6%) and VV (33.8%) ECMO support. There was significant increase in BTE incidence for nonsurvivors compared with survivors with VA ECMO (55.4% vs 26.5%; P < .001) and VV ECMO (58.1% vs 18.4%; P = .01). Male sex, increased age, pre–extracorporeal life support (ECLS) cardiac arrest, cannulation for extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR), and elevated lactate were predictive of in-hospital mortality in the VA ECMO cohort. In conclusion, in adult patients with SCD, in-hospital survival was significantly lower with VA ECMO than VV ECMO. Male sex, increased age, eCPR support, elevated lactate, and pre-ECLS arrest were strongest indicators of VA ECMO mortality. Bleeding and thrombotic complications have an association with inpatient mortality for those treated with ECMO.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an autosomally inherited hemoglobinopathy that results in polymerization of mutant hemoglobin when intravascular oxygen tension is low, leading to altered red cell rheology, hemolysis, and microcirculatory vaso-occlusion.1,2 For patients with SCD, cardiopulmonary complications such as pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular failure, and acute chest syndrome (ACS) occur at higher frequency and are major risk factors for death.3-6 With improvements in technology and the growth of capable centers, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is being progressively used in the management of cardiopulmonary failure when conventional treatment is insufficient. As use expands, there is a critical need to further understand the role of ECMO in unique populations such as those with SCD for whom support may increasingly be considered.7 Given the pathophysiology of SCD, hematologic aberrancies and disease-specific sequelae have the potential to add significant complexity to ECMO-related decision-making and management. Unfortunately, data on ECMO use for respiratory and cardiac insufficiency in adult patients with SCD undergoing either venovenous (VV) or venoarterial (VA) ECMO support are very limited, leaving little guidance on the optimal approach in these individuals.6,8-12 We hypothesized that adult patients with SCD may have high mortality on ECMO and those who do not survive VA or VV ECMO are more likely to experience bleeding and thrombotic events (BTEs) than those who survive. To better understand the use of ECMO in adult patients of any age with SCD, we queried the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry to characterize SCD cohorts that were treated with VV or VA ECMO, investigate ECMO-related outcomes, and identify clinical factors that may be predictive of survival in this population.

Methods

Data source

The ELSO registry, a voluntary international registry of extracorporeal life support (ECLS) including >400 centers, was queried from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2024 using International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9/-10-CM) SCD–associated codes. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval as a retrospective analysis of deidentified registry data.

Population and data extraction

Included patients were adults (aged ≥18 years), who received ECLS via any configuration, and had SCD-associated ICD-9/-10-CMs codes of D57.XX and 282.XX. The full list of included ICD-9/-10-CMs is detailed within the supplemental Appendix. Sickle cell trait (SCT) ICD-9/-10-CM codes were excluded from primary analysis. Patient who received hybrid strategy ECMO (eg, VV-arterial [VVA] ECMO) were grouped with the VA ECMO cohort. Patients with multiple ECLS runs were included. However, only data from first run were used for analysis. Data extracted included baseline characteristics, diagnoses, laboratory values, vital signs, hemodynamic parameters, mechanical ventilation and respiratory data, ECMO circuit characteristics, cannula configuration, and clinical outcomes. Laboratory values, vital signs, hemodynamic parameters, and respiratory data were obtained before cannulation and 24 hours after cannulation.

Objectives, outcomes, and definitions

The primary objective was to evaluate in-hospital mortality and clinical outcomes of adult patients with SCD supported with ECMO, including BTEs. BTEs were stratified by ECMO modality (VA vs VV ECMO) and mortality status (survivors vs nonsurvivors). Bleeding outcomes included medical and surgical bleeding. Medical bleeding was defined as presence of pulmonary hemorrhage, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, intraparenchymal/extraparenchymal central nervous system hemorrhage, or intraventricular hemorrhage. Surgical bleeding was defined as cardiac tamponade or presence of surgical site, peripheral cannulation site, or mediastinal cannulation site bleeding. Thrombotic complications included moderate hemolysis, severe hemolysis, central nervous system infarction, circuit change, circuit thrombosis, and pump failure. Supplemental Table 1 describes ELSO registry clinical outcomes definitions. The secondary objective was to assess the association of key baseline characteristics with in-hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using R statistical software (version 4.3.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The STORBE (strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) checklist for cohort studies was used. Patients were stratified by both ECMO configuration (VA vs VV ECMO) and in-hospital mortality (survivors vs nonsurvivors). Sample size was determined pragmatically via number of patients with SCD-associated ICD-9-10-CM codes within the ELSO registry.

Categorical variables are reported as number and percentage; Pearson χ2 test or the Fisher exact test was used for comparison. Parametric continuous data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and difference in means was compared using an independent samples t test. Nonparametric continuous data are reported as median (25th-75th percentile) and was analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Two-sided P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. To visualize increasing use of ECMO over time, the ggplot2 package was used to develop line graphs.

An exploratory post hoc analysis was designed to assist with patient prognostication. Two multivariable logistic regression models (VA and VV ECMO model) assessing the association of precannulation factors with in-hospital mortality were developed using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) logistic regression via the glmnet package. To account for missing data, nonparametric missing value imputation using the random forest method was used with the missForest package. Methods are detailed further in the supplemental Appendix.

Results

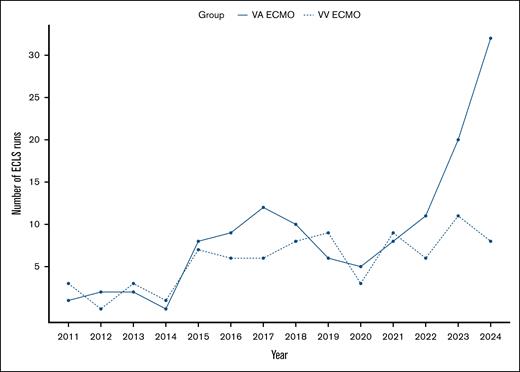

In the ELSO registry, 254 patients were identified. Of these, 206 patients had ICD-9/-10-CM codes for SCD or disorder. Forty-eight patients had a diagnosis of SCT (D57.3 or 282.5) and were excluded from primary analysis. Of 206 included patients, 126 received cannulation for VA ECMO (4 received VVA ECMO therapy) and 80 were treated with VV ECMO. Four patients received cannulation on 2 separate times and 2 patients received cannulation on 3 separate times. Figure 1 depicts increasing use of VA ECMO in patients with SCD.

The use of VA ECMO in adult patients with SCD has risen over the past decade, whereas VV ECMO use remains relatively unchanged.

The use of VA ECMO in adult patients with SCD has risen over the past decade, whereas VV ECMO use remains relatively unchanged.

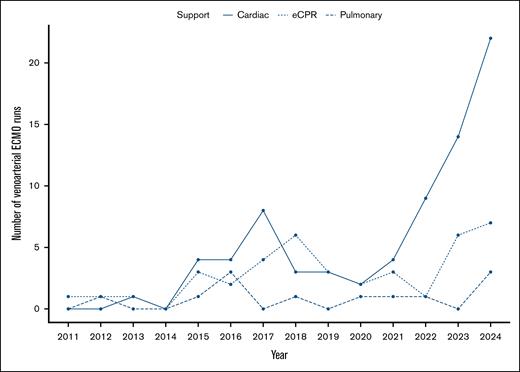

Within the last 5 years, VA ECMO use for cardiac support in patients with SCD has increased, whereas pulmonary and extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR) support remained relatively unchanged (Figure 2).

VA ECMO use for cardiac support has risen sharply over the past 5 years in adult patients with SCD.

VA ECMO use for cardiac support has risen sharply over the past 5 years in adult patients with SCD.

Table 1 displays baseline characteristics of patients on VA ECMO.

VA ECMO baseline characteristics

| . | Total (n = 126) . | Survivors (n = 34) . | Nonsurvivors (n = 92) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (25th-75th percentile), y | 33 (25-44) | 27 (21-37) | 34 (26-47) | .01 |

| Sex, n (%) | .21 | |||

| Male | 69 (54.8) | 15 (44.1) | 54 (58.7) | |

| Female | 57 (45.2) | 19 (55.9) | 38 (41.3) | |

| Weight, median (25th-75th percentile), kg | 75 (62-90) | 74 (58.7-86.8) | 77.1 (64.1-90.4) | .23 |

| Height, mean ± SD, cm | 169.6 ± 11.6 | 169.1 ± 9.3 | 169.8 ± 12.5 | .78 |

| BMI, median (25th-75th percentile), kg/m2 | 26 (22.3-30.5) | 24.2 (21-30.6) | 26 (22.7-30.3) | .78 |

| Race, n (%) | .08 | |||

| Black | 100 (79.4) | 29 (85.3) | 71 (77.2) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (5.6) | 1 (2.9) | 6 (6.5) | |

| Middle Eastern/Northern African | 2 (1.6) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Native American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| White | 7 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (7.6) | |

| Multiple | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 3 (2.4) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Unknown | 6 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 6 (6.5) | |

| Support type, n (%) | .02 | |||

| Cardiac | 74 (58.7) | 23 (67.6) | 51 (55.4) | |

| eCPR | 40 (31.7) | 5 (14.7) | 35 (38) | |

| Pulmonary | 12 (9.5) | 6 (17.6) | 6 (6.5) | |

| Pre-ECLS arrest, n (%) | 69 (54.8) | 12 (35.3) | 57 (62) | .009 |

| Ventilator status, n (%) | .43 | |||

| Conventional | 67 (53.2) | 22 (64.7) | 45 (48.5) | |

| No ventilator | 17 (13.5) | 3 (8.8) | 14 (15.2) | |

| HFO | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Other | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Ventilatory settings | ||||

| Respiratory rate (breaths per min), mean ± SD | 23 ± 7 | 24 ± 7 | 23 ± 7 | .54 |

| FiO2, median (25th-75th percentile), % | 100 (89-100) | 100 (86-100) | 100 (100-100) | .43 |

| PIP, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 30 (25-38) | 30 (21-35) | 31 (28-38) | .20 |

| PEEP, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 8 (5-12) | 6 (5-8) | 10 (5-13) | .06 |

| Mean airway pressure, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 17 (11-24) | 12 (10-15) | 19 (13-25) | .03 |

| Required hand-bagging, n (%) | 19 (15.1) | 3 (8.8) | 16 (17.4) | .12 |

| Laboratory values and vital signs | ||||

| pH, median (25th-75th percentile) | 7.18 (7.04-7.30) | 7.26 (7.12-7.33) | 7.14 (7.02-7.29) | .09 |

| pCO2, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 50 ± 23 | 47 ± 20 | 51 ± 24 | .45 |

| pO2, median (25th-75th percentile), mm Hg | 101 (64-182) | 149 (89-293) | 90 (63-164) | .06 |

| Serum bicarbonate, mean ± SD, mmol/L | 17 ± 6 | 19 ± 7 | 17 ± 6 | .14 |

| SaO2, median (25th-75th percentile), % | 95 (84-99) | 98 (95-100) | 93 (84-98) | .02 |

| Lactate, median (25th-75th percentile), mmol/L | 11.2 (5.7-15.4) | 6.8 (3.4-9.3) | 13.2 (6.4-16) | .02 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 95 ± 35 | 109 ± 37 | 89 ± 33 | .01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 58 ± 23 | 66 ± 25 | 55 ± 21 | .03 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 70 ± 25 | 80 ± 26 | 65 ± 23 | .02 |

| Pulse pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 35 ± 23 | 42 ± 29 | 32 ± 20 | .17 |

| . | Total (n = 126) . | Survivors (n = 34) . | Nonsurvivors (n = 92) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (25th-75th percentile), y | 33 (25-44) | 27 (21-37) | 34 (26-47) | .01 |

| Sex, n (%) | .21 | |||

| Male | 69 (54.8) | 15 (44.1) | 54 (58.7) | |

| Female | 57 (45.2) | 19 (55.9) | 38 (41.3) | |

| Weight, median (25th-75th percentile), kg | 75 (62-90) | 74 (58.7-86.8) | 77.1 (64.1-90.4) | .23 |

| Height, mean ± SD, cm | 169.6 ± 11.6 | 169.1 ± 9.3 | 169.8 ± 12.5 | .78 |

| BMI, median (25th-75th percentile), kg/m2 | 26 (22.3-30.5) | 24.2 (21-30.6) | 26 (22.7-30.3) | .78 |

| Race, n (%) | .08 | |||

| Black | 100 (79.4) | 29 (85.3) | 71 (77.2) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (5.6) | 1 (2.9) | 6 (6.5) | |

| Middle Eastern/Northern African | 2 (1.6) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Native American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| White | 7 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 7 (7.6) | |

| Multiple | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 3 (2.4) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Unknown | 6 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 6 (6.5) | |

| Support type, n (%) | .02 | |||

| Cardiac | 74 (58.7) | 23 (67.6) | 51 (55.4) | |

| eCPR | 40 (31.7) | 5 (14.7) | 35 (38) | |

| Pulmonary | 12 (9.5) | 6 (17.6) | 6 (6.5) | |

| Pre-ECLS arrest, n (%) | 69 (54.8) | 12 (35.3) | 57 (62) | .009 |

| Ventilator status, n (%) | .43 | |||

| Conventional | 67 (53.2) | 22 (64.7) | 45 (48.5) | |

| No ventilator | 17 (13.5) | 3 (8.8) | 14 (15.2) | |

| HFO | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Other | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Ventilatory settings | ||||

| Respiratory rate (breaths per min), mean ± SD | 23 ± 7 | 24 ± 7 | 23 ± 7 | .54 |

| FiO2, median (25th-75th percentile), % | 100 (89-100) | 100 (86-100) | 100 (100-100) | .43 |

| PIP, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 30 (25-38) | 30 (21-35) | 31 (28-38) | .20 |

| PEEP, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 8 (5-12) | 6 (5-8) | 10 (5-13) | .06 |

| Mean airway pressure, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 17 (11-24) | 12 (10-15) | 19 (13-25) | .03 |

| Required hand-bagging, n (%) | 19 (15.1) | 3 (8.8) | 16 (17.4) | .12 |

| Laboratory values and vital signs | ||||

| pH, median (25th-75th percentile) | 7.18 (7.04-7.30) | 7.26 (7.12-7.33) | 7.14 (7.02-7.29) | .09 |

| pCO2, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 50 ± 23 | 47 ± 20 | 51 ± 24 | .45 |

| pO2, median (25th-75th percentile), mm Hg | 101 (64-182) | 149 (89-293) | 90 (63-164) | .06 |

| Serum bicarbonate, mean ± SD, mmol/L | 17 ± 6 | 19 ± 7 | 17 ± 6 | .14 |

| SaO2, median (25th-75th percentile), % | 95 (84-99) | 98 (95-100) | 93 (84-98) | .02 |

| Lactate, median (25th-75th percentile), mmol/L | 11.2 (5.7-15.4) | 6.8 (3.4-9.3) | 13.2 (6.4-16) | .02 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 95 ± 35 | 109 ± 37 | 89 ± 33 | .01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 58 ± 23 | 66 ± 25 | 55 ± 21 | .03 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 70 ± 25 | 80 ± 26 | 65 ± 23 | .02 |

| Pulse pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 35 ± 23 | 42 ± 29 | 32 ± 20 | .17 |

Includes patients with hybrid cannulation strategies (eg, VVA ECMO).

BMI, body mass index; HFO, high-frequency oscillatory ventilation; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; pCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PIP, peak inspiratory pressure; pO2, partial pressure of oxygen; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; SD, standard deviation.

Patients were young (median age, 33 years) and received VA ECMO mostly for cardiac support (58.7%). Forty patients (31.7%) on VA ECMO received eCPR. VA ECMO recipient nonsurvivors were older; experienced more pre-ECLS cardiac arrest; had higher serum lactate; and had lower systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and mean arterial pressure before cannulation than survivors. Supplemental Table 2 details relevant laboratory values and vital signs after 24 hours on VA ECMO.

Table 2 portrays baseline characteristics of patients on VV ECMO.

VV ECMO baseline characteristics

| . | Total (n = 80) . | Survivors (n = 49) . | Nonsurvivors (n = 31) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (25th-75th percentile), y | 26 (22-31) | 25 (22-31) | 27 (22-35) | .29 |

| Sex, n (%) | .52 | |||

| Male | 41 (51.3) | 25 (51) | 16 (51.6) | |

| Female | 37 (46.3) | 22 (44.9) | 15 (48.4) | |

| Unknown | 2 (2.5) | 2 (4.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Weight, median (25th-75th percentile), kg | 74.1 (63.6-91) | 73 (62.8-90.4) | 80 (65.8-93.2) | .36 |

| Height, mean ± SD, cm | 168.1 ± 11.2 | 167.8 ± 10.9 | 168.5 ± 11.8 | .81 |

| BMI, median (25th-75th percentile), kg/m2 | 26.4 (23.1-31) | 26.6 (22.8-30.5) | 28.2 (23.2-32) | .90 |

| Race, n (%) | .25 | |||

| Black | 66 (82.5) | 39 (79.6) | 27 (87.1) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Middle Eastern/Northern African | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Native American | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| White | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Multiple | 6 (7.5) | 6 (12.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 2 (2.5) | 1 (2) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Unknown | 3 (3.8) | 2 (4.1) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Support type, n (%) | — | |||

| Cardiac | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| eCPR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pulmonary | 80 (100) | 49 (100) | 31 (100) | |

| Pre-ECLS arrest, n (%) | 8 (10) | 4 (8.2) | 4 (12.9) | .76 |

| Ventilator status, n (%) | .17 | |||

| Conventional | 64 (80) | 39 (79.6) | 25 (80.6) | |

| No ventilator | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| HFO | 3 (3.8) | 3 (6.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Ventilator settings | ||||

| Respiratory rate (breaths per min), mean ± SD | 25 ± 8 | 24 ± 8 | 26 ± 7 | .33 |

| FiO2, median (25th-75th percentile), % | 100 (100-100) | 100 (100-100) | 100 (91-100) | .19 |

| PIP, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 36 (32-43) | 37 (31-46) | 35 (34-37) | .18 |

| PEEP, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 14 (10-17) | 14 (10-18) | 12 (10-14) | .25 |

| Mean airway pressure, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 23 (19-26) | 24 (20-28) | 20 (19-23) | .02 |

| Required hand-bagging, n (%) | 9 (11.3) | 5 (10.2) | 4 (12.9) | .36 |

| Laboratory values and vital signs | ||||

| pH, median (25th-75th percentile) | 7.28 (7.19-7.36) | 7.30 (7.20-7.37) | 7.25 (7.20-7.34) | .59 |

| pCO2, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 57 ± 19 | 56 ± 20 | 57 ± 18 | .85 |

| pO2, median (25th-75th percentile), mm Hg | 65 (55-79) | 66 (56-76) | 64 (55-82) | .96 |

| Serum bicarbonate, mean ± SD, mmol/L | 26 ± 7 | 26 ± 6 | 26 ±8 | .94 |

| SaO2, median (25th-75th percentile), % | 89 (81-94) | 89 (80-93) | 91 (82-95) | .88 |

| Lactate, median (25th-75th percentile), mmol/L | 2.4 (1.1-3.9) | 2.4 (1.1-3.9) | 2.5 (1.3-3.6) | .87 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 116 ± 24 | 115 ± 25 | 116 ± 23 | .95 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 63 ± 17 | 63 ± 19 | 64 ± 14 | .88 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 78 ± 19 | 78 ± 21 | 78 ± 18 | .88 |

| Pulse pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 51 ± 18 | 51 ± 18 | 52 ± 18 | .87 |

| . | Total (n = 80) . | Survivors (n = 49) . | Nonsurvivors (n = 31) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (25th-75th percentile), y | 26 (22-31) | 25 (22-31) | 27 (22-35) | .29 |

| Sex, n (%) | .52 | |||

| Male | 41 (51.3) | 25 (51) | 16 (51.6) | |

| Female | 37 (46.3) | 22 (44.9) | 15 (48.4) | |

| Unknown | 2 (2.5) | 2 (4.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Weight, median (25th-75th percentile), kg | 74.1 (63.6-91) | 73 (62.8-90.4) | 80 (65.8-93.2) | .36 |

| Height, mean ± SD, cm | 168.1 ± 11.2 | 167.8 ± 10.9 | 168.5 ± 11.8 | .81 |

| BMI, median (25th-75th percentile), kg/m2 | 26.4 (23.1-31) | 26.6 (22.8-30.5) | 28.2 (23.2-32) | .90 |

| Race, n (%) | .25 | |||

| Black | 66 (82.5) | 39 (79.6) | 27 (87.1) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Middle Eastern/Northern African | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Native American | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| White | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Multiple | 6 (7.5) | 6 (12.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 2 (2.5) | 1 (2) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Unknown | 3 (3.8) | 2 (4.1) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Support type, n (%) | — | |||

| Cardiac | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| eCPR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pulmonary | 80 (100) | 49 (100) | 31 (100) | |

| Pre-ECLS arrest, n (%) | 8 (10) | 4 (8.2) | 4 (12.9) | .76 |

| Ventilator status, n (%) | .17 | |||

| Conventional | 64 (80) | 39 (79.6) | 25 (80.6) | |

| No ventilator | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| HFO | 3 (3.8) | 3 (6.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Ventilator settings | ||||

| Respiratory rate (breaths per min), mean ± SD | 25 ± 8 | 24 ± 8 | 26 ± 7 | .33 |

| FiO2, median (25th-75th percentile), % | 100 (100-100) | 100 (100-100) | 100 (91-100) | .19 |

| PIP, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 36 (32-43) | 37 (31-46) | 35 (34-37) | .18 |

| PEEP, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 14 (10-17) | 14 (10-18) | 12 (10-14) | .25 |

| Mean airway pressure, median (25th-75th percentile), cm H2O | 23 (19-26) | 24 (20-28) | 20 (19-23) | .02 |

| Required hand-bagging, n (%) | 9 (11.3) | 5 (10.2) | 4 (12.9) | .36 |

| Laboratory values and vital signs | ||||

| pH, median (25th-75th percentile) | 7.28 (7.19-7.36) | 7.30 (7.20-7.37) | 7.25 (7.20-7.34) | .59 |

| pCO2, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 57 ± 19 | 56 ± 20 | 57 ± 18 | .85 |

| pO2, median (25th-75th percentile), mm Hg | 65 (55-79) | 66 (56-76) | 64 (55-82) | .96 |

| Serum bicarbonate, mean ± SD, mmol/L | 26 ± 7 | 26 ± 6 | 26 ±8 | .94 |

| SaO2, median (25th-75th percentile), % | 89 (81-94) | 89 (80-93) | 91 (82-95) | .88 |

| Lactate, median (25th-75th percentile), mmol/L | 2.4 (1.1-3.9) | 2.4 (1.1-3.9) | 2.5 (1.3-3.6) | .87 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 116 ± 24 | 115 ± 25 | 116 ± 23 | .95 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 63 ± 17 | 63 ± 19 | 64 ± 14 | .88 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 78 ± 19 | 78 ± 21 | 78 ± 18 | .88 |

| Pulse pressure, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 51 ± 18 | 51 ± 18 | 52 ± 18 | .87 |

Patients on VV ECMO patients were young (median age, 26 years) and had few differences in baseline characteristics among survivors and nonsurvivors. Supplemental Table 3 details relevant laboratory values and vital signs after 24 hours of VV ECMO support.

BTEs were common and higher in nonsurvivors with both VA (47.6%) and VV (33.8%) ECMO. Table 3 summarizes BTEs.

VA and VV ECMO bleeding and thrombotic outcomes

| . | Total (n = 126) . | Survivors (n = 34) . | Nonsurvivors (n = 92) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA ECMO | ||||

| BTEs | 60 (47.6) | 9 (26.5) | 51 (55.4) | .01 |

| Hemorrhagic complication | 46 (36.5) | 6 (17.6) | 40 (43.5) | .007 |

| Medical hemorrhage | 21 (16.7) | 1 (2.9) | 20 (21.7) | .01 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 4 (3.2) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (3.3) | 1 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 8 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 8 (8.7) | .11 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 10 (7.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (10.9) | .06 |

| Surgical hemorrhage | 29 (23) | 5 (14.7) | 24 (26.1) | .26 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 3 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.3) | .56 |

| Peripheral cannulation site bleeding | 18 (14.3) | 3 (8.8) | 15 (16.3) | .39 |

| Mediastinal cannulation site bleeding | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 |

| Surgical site bleeding | 9 (7.1) | 2 (5.9) | 5 (7.6) | 1 |

| Thrombotic complication | 24 (19) | 4 (11.8) | 20 (20.7) | .31 |

| ECMO circuit thrombosis | 9 (7.1) | 1 (2.9) | 8 (8.7) | .44 |

| ECMO oxygenator failure | 5 (4) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (4.3) | 1 |

| Moderate hemolysis | 4 (3.2) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (3.3) | 1 |

| Severe hemolysis | 6 (4.8) | 2 (5.9) | 4 (4.3) | .66 |

| CNS infarct | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.3) | .57 |

| VV ECMO | n = 80 | n = 49 | n = 31 | |

| BTEs | 27 (33.8) | 9 (18.4) | 18 (58.1) | <.001 |

| Hemorrhagic complication | 17 (21.3) | 5 (10.2) | 12 (38.7) | .004 |

| Medical hemorrhage | 9 (11.3) | 1 (2) | 8 (25.8) | .002 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 3 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.7) | .05 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.9) | .02 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 3 (3.8) | 1 (2) | 2 (6.5) | .56 |

| Surgical hemorrhage | 8 (10) | 4 (8.2) | 4 (12.9) | .70 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | -- |

| Peripheral cannulation site bleeding | 5 (6.3) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (6.5) | 1 |

| Mediastinal cannulation site bleeding | 2 (2.5) | 1 (2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 |

| Surgical site bleeding | 2 (2.5) | 2 (4.1) | 0 (0) | .52 |

| Thrombotic complication | 16 (20) | 6 (12.2) | 10 (32.3) | .04 |

| ECMO circuit thrombosis | 6 (7.5) | 2 (4.1) | 4 (12.9) | .20 |

| ECMO oxygenator failure | 5 (6.9) | 1 (2.3) | 4 (12.9) | .20 |

| Moderate hemolysis | 2 (2.5) | 1 (2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 |

| Severe hemolysis | 6 (7.5) | 2 (4.1) | 4 (12.9) | .20 |

| CNS infarct | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | .15 |

| . | Total (n = 126) . | Survivors (n = 34) . | Nonsurvivors (n = 92) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA ECMO | ||||

| BTEs | 60 (47.6) | 9 (26.5) | 51 (55.4) | .01 |

| Hemorrhagic complication | 46 (36.5) | 6 (17.6) | 40 (43.5) | .007 |

| Medical hemorrhage | 21 (16.7) | 1 (2.9) | 20 (21.7) | .01 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 4 (3.2) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (3.3) | 1 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 8 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 8 (8.7) | .11 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 10 (7.9) | 0 (0) | 10 (10.9) | .06 |

| Surgical hemorrhage | 29 (23) | 5 (14.7) | 24 (26.1) | .26 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 3 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.3) | .56 |

| Peripheral cannulation site bleeding | 18 (14.3) | 3 (8.8) | 15 (16.3) | .39 |

| Mediastinal cannulation site bleeding | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 |

| Surgical site bleeding | 9 (7.1) | 2 (5.9) | 5 (7.6) | 1 |

| Thrombotic complication | 24 (19) | 4 (11.8) | 20 (20.7) | .31 |

| ECMO circuit thrombosis | 9 (7.1) | 1 (2.9) | 8 (8.7) | .44 |

| ECMO oxygenator failure | 5 (4) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (4.3) | 1 |

| Moderate hemolysis | 4 (3.2) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (3.3) | 1 |

| Severe hemolysis | 6 (4.8) | 2 (5.9) | 4 (4.3) | .66 |

| CNS infarct | 4 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.3) | .57 |

| VV ECMO | n = 80 | n = 49 | n = 31 | |

| BTEs | 27 (33.8) | 9 (18.4) | 18 (58.1) | <.001 |

| Hemorrhagic complication | 17 (21.3) | 5 (10.2) | 12 (38.7) | .004 |

| Medical hemorrhage | 9 (11.3) | 1 (2) | 8 (25.8) | .002 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 3 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.7) | .05 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 4 (12.9) | .02 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 3 (3.8) | 1 (2) | 2 (6.5) | .56 |

| Surgical hemorrhage | 8 (10) | 4 (8.2) | 4 (12.9) | .70 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | -- |

| Peripheral cannulation site bleeding | 5 (6.3) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (6.5) | 1 |

| Mediastinal cannulation site bleeding | 2 (2.5) | 1 (2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 |

| Surgical site bleeding | 2 (2.5) | 2 (4.1) | 0 (0) | .52 |

| Thrombotic complication | 16 (20) | 6 (12.2) | 10 (32.3) | .04 |

| ECMO circuit thrombosis | 6 (7.5) | 2 (4.1) | 4 (12.9) | .20 |

| ECMO oxygenator failure | 5 (6.9) | 1 (2.3) | 4 (12.9) | .20 |

| Moderate hemolysis | 2 (2.5) | 1 (2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 |

| Severe hemolysis | 6 (7.5) | 2 (4.1) | 4 (12.9) | .20 |

| CNS infarct | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | .15 |

Data are presented as n (%).

CNS, central nervous system.

Surgical hemorrhage (23%) was more common than medical hemorrhage (16.7%) among VA ECMO patients. Although there was no significant difference in surgical hemorrhage or thrombotic complications, there was more medical hemorrhage in VA ECMO recipient nonsurvivors vs survivors (21.7% vs 2.9%; P = .01). For patients receiving VV ECMO, the incidence of medical hemorrhage (11.5%) and surgical hemorrhage (10%) was similar. In addition, medical hemorrhage (25.8% vs 2%; P = .002) and thrombosis (32.3% vs 12.2%; P = .04) were significantly more common in nonsurvivors compared with survivors. There was no difference in ECMO duration among VA ECMO patients who experienced BTEs and those who did not (99 hours [25th-75th percentile, 36-139] vs 64 hours [25th-75th percentile,16-150]; P = .20), whereas VV ECMO duration was significantly greater in patients who experienced BTEs (346 hours [25th-75th percentile, 210-558] BTE vs 142 hours [25th-75th percentile, 104-195] no BTE; P < .001). Supplemental Tables 4 and 5 further detail important clinical outcomes of VA and VV ECMO support.

A total of 83 patients (40.3%) in the full cohort were discharged alive; VA ECMO in-hospital survival was 27% and VV ECMO in-hospital survival was 61.3% (P < .001). Although indication for ECMO was often difficult to discern, primary diagnosis for all patients and associated in-hospital mortality are detailed in Supplemental Table 6.

Table 4 displays full results of LASSO logistic regression analysis assessing the association of precannulation factors with in-hospital mortality in patients with SCD receiving VA ECMO.

LASSO regression variable selection and coefficients for model assessing pre-ECLS predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with SCD on VA ECMO

| Variable . | LASSO β coefficient . |

|---|---|

| Sex, male | 0.220 |

| Age, per 1-year increase | 0.045 |

| Support type, reference cardiac | |

| eCPR | 0.427 |

| Pulmonary | −0.126 |

| pO2, per 1–mm Hg increase | −0.003 |

| Serum bicarbonate, per 1-mmol/L increase | −0.026 |

| Mean arterial pressure, per 1–mm Hg increase | −0.009 |

| Pulse pressure, per 1–mm Hg increase | −0.004 |

| Pre-ECLS cardiac arrest | 0.449 |

| Lactate, per 1-mmol/L increase | 0.086 |

| Variable . | LASSO β coefficient . |

|---|---|

| Sex, male | 0.220 |

| Age, per 1-year increase | 0.045 |

| Support type, reference cardiac | |

| eCPR | 0.427 |

| Pulmonary | −0.126 |

| pO2, per 1–mm Hg increase | −0.003 |

| Serum bicarbonate, per 1-mmol/L increase | −0.026 |

| Mean arterial pressure, per 1–mm Hg increase | −0.009 |

| Pulse pressure, per 1–mm Hg increase | −0.004 |

| Pre-ECLS cardiac arrest | 0.449 |

| Lactate, per 1-mmol/L increase | 0.086 |

Minimum mean squared error was achieved when penalty, λ, was set to 0.0270187. Male sex, increased age, eCPR support, pre-ECLS cardiac arrest, and elevated lactate were associated with increased odds of in-hospital mortality in the final model; whereas pulmonary support, increased partial pressure of oxygen, increased serum bicarbonate, higher mean arterial pressure, and increased pulse pressure were inversely associated with in-hospital mortality. Pre-ECLS cardiac arrest had the largest β coefficient (0.449). Because of the low event rate and small VV ECMO cohort size, LASSO regression was unable to identify any significant associations between precannulation covariates and in-hospital mortality (data not shown).

Discussion

Given the paucity of literature describing ECLS in adults with SCD, this multicenter investigation provides valuable insight into the role of this life-saving therapy with rising use in a unique population. A critical unanswered question for individuals with complex hematologic disorders such as SCD is whether the therapeutic benefit of high blood flow extracorporeal modalities such as ECMO might be limited by the underlying disease pathophysiology. To explore this unknown, we evaluated important clinical outcomes for all adults with SCD treated with VV or VA ECMO in the ELSO registry. We hypothesized that adult patients with SCD may have high mortality on ECMO and those who do not survive are more likely to experience BTEs.

Our study found that individuals with SCD who were placed on VV ECMO had a similar in-hospital survival rate of 61.3% compared with 58% for total adult VV ECMO patients in the ELSO registry.13 This finding supports this modality’s use in those with SCD. However, it is noted that with a median age of 26 years, the SCD cohort was likely much younger than the comprehensive adult ELSO VV ECMO cohort. Given that age and other key clinical variables influence mortality, survival rates may differ significantly when comparing patients with SCD with more closely matched cohorts without SCD. For those treated with VA ECMO, we found that survival was only 27% for individuals with SCD, substantially lower than the 44% survival rate for total adult patients receiving VA ECMO in the ELSO registry.13 The high mortality is particularly striking given the relatively young median age of 33 years for the SCD cohort placed on VA ECMO. Although the reasons for this survival discrepancy are unclear, it is probable that SCD-related disease features and severity are important factors. Unfortunately, there is no validated metric of illness severity or baseline comorbidity index readily available in the ELSO registry, which, similar to age, should correlate with ECLS outcomes. There are also likely important differences between causes of clinical decline between the young SCD cohort, prone to distinct SCD-related cardiopulmonary complications, and the broad adult ELSO registry cohort.14 Although our study does not fully capture the clinical etiologies leading to indication for ECMO, which is a key limitation, a comprehensive understanding is crucial for more robust comparative analyses.

The existing literature on ECMO in adults with SCD is largely limited to case reports, small case series, and 1 additional ELSO registry analysis.8-12 The aforementioned ELSO study focused on only young adults (aged <40 years) treated with ECMO from 1998 to 2022 and included a much smaller sample size (n = 110) than the analysis presented in this report including all adults (n = 206). The larger sample size in our cohort was driven by inclusion of patients aged ≥40 years, as well as inclusion of 71 additional adults with SCD who received cannulation for ECMO in 2023 and 2024. Notably, VA ECMO survival was lower in our study than the previous ELSO registry study (27% vs 36%).12 We suspect this difference in survival was because, in part, of inclusion of an older cohort in our analysis, with VA ECMO survival in patients aged ≥40 years having been significantly lower than for those aged <40 years (14.6% vs 32.9%; P = .03).12 In addition, there is a notable multicenter study from France that investigated adults (aged >18 years) hospitalized for ACS who were treated with VA or VV ECMO.6 ACS is a life-threatening illness unique to SCD caused by vaso-occlusion in pulmonary vasculature with subsequent impairment in blood flow and gas exchange.15 The French study, including 12 patients on VA ECMO and 10 on VV ECMO, reported low overall survival rates of 16.7% and 40%, respectively. Although both this investigation and our analysis report high VA ECMO mortality and include adult SCD cohorts of similar average age, the reason for the discrepancy in survival between the 2 studies remains unclear. Notably, differences in study design and registry data limitations prevent more direct, rigorous comparisons.6 Our analysis encompasses a broad international cohort with various causes of cardiac and/or respiratory failure, whereas the French study focused on a smaller, relatively homogenous group of patients from a limited number of centers who were hospitalized with ACS.6 Undoubtedly, the driving etiology of clinical instability such as ACS that leads to the need for ECLS is a critical variable in the determination of patient outcomes.

Cardiopulmonary complications are common in SCD and significantly increase mortality risk.14,16,17 Among adults with SCD, ACS and complications of pulmonary hypertension are the leading causes of death.6,14,15,18-20 Although ACS can cause severe lung injury that necessitates VV ECMO for pulmonary support, acute elevations in pulmonary afterload that may occur in this setting can lead to right ventricular dysfunction, cor pulmonale, and cardiogenic shock requiring consideration of VA ECMO for cardiac support.6,10 In addition to ACS, pathologies that can cause cardiopulmonary decompensation are pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary embolism, both of which are frequent complications of SCD that may prompt need for mechanical support with VA ECMO.3,14,17 Hybrid strategies such as VVA ECMO have been used in adults with SCD as reported in this study (n = 4). Although not captured in the ELSO registry until recently, use of veno-pulmonary artery ECMO might also be considered in patients with SCD, particularly in the setting of concomitant right ventricular and pulmonary failure.10 Selection of the most appropriate ECMO strategy is crucial for achieving optimal outcomes and should be driven by a thorough understanding of both the mechanisms of clinical decompensation and the unique pathophysiological aspects of SCD.

BTEs are the most common ECMO-related complications and are linked to in-hospital mortality.21-23 The interaction of blood and large synthetic surfaces can lead to coagulopathy through activation of inflammation, platelet dysfunction, fibrinolysis, and coagulation pathway dysregulation, particularly with high blood flow extracorporeal therapies.24 Although SCD, itself, is associated with hypercoagulability and increased thrombotic risk, patients with SCD are also more prone to bleeding.25,26 In addition, shear forces associated with ECMO may exacerbate hemolysis, a fundamental feature of SCD.27 Thus, it is possible that hematologic aspects of SCD may worsen hemocompatibility on ECMO and increase incidence of BTE. We hypothesized that adults with SCD who do not survive ECMO are more likely to experience BTEs than survivors. In our study, moderate to severe hemolysis rates in patients with SCD were surprisingly modest with only 8% and 10% experiencing this complication on VA and VV ECMO, respectively, whereas rates of hemolysis in general adult ELSO registry cohorts of 6.8% on VA ECMO and 5.3% on VV ECMO have been reported.21,22 BTE occurred in 47.6% of patients with SCD on VA ECMO. Most total BTEs were secondary to surgical hemorrhage, including 14.3% cannulation-related and 7.1% surgical site bleeding. This is remarkably similar to an ELSO registry analysis looking at BTEs in general adult patients undergoing VA ECMO therapy from 2010 to 2017, which found a BTE incidence of 44.1%. Most of these events were also secondary to surgical hemorrhage including 23.5% cannulation-related and 20.8% surgical site bleeding.21 There was a significant difference in mortality for individuals with SCD on VA ECMO who experienced BTE (P = .01). This was also true in the VA ECMO ELSO registry analysis, which reported a cumulative association with BTEs and mortality in a general adult cohort.21 For adult patients with SCD who underwent VV ECMO, BTE incidence was 33.8%, which was again, similar to reported incidence of 40.2% in a separate ELSO registry study of general adult patients requiring VV ECMO from 2010 to 2017.22 Thrombotic complications occurred in 20% and 25.3% of individuals experiencing these on VV ECMO in the SCD and general adult ECMO cohorts, respectively. In patients with SCD, bleeding events occurred in 21.3%, and medical hemorrhage (11.3%) was slightly more common than surgical hemorrhage (10%). Both hemorrhagic and thrombotic complications were associated with mortality on VV ECMO. Similarly, BTE in the general adult VV ECMO ELSO cohort had a strong, cumulative association with in-hospital mortality.22

The comparable incidence and outcomes of BTEs in patients with SCD and general adult cohorts reported in ELSO data set analyses are encouraging. However, important limitations exist. Although the diagnosis codes for SCT (D57.3 or 282.5) were excluded, we included 26 patients in the final analysis with an ICD-9/-10-CM code of D57 (sickle cell disorders). This diagnosis code with imperfect specificity may have resulted in the inclusion of a small number of patients with SCT and not true disease. In addition, it was not possible to match and directly compare SCD and general adult ECMO cohorts, which is a significant limitation in this study. Transfusion practices, anticoagulation approaches, coagulation measurements, hematologic laboratory values, and SCD-focused interventions such as exchange transfusion are not captured in the ELSO registry, nor are several BTE outcomes that are relevant to SCD pathophysiology such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and arterial thrombosis. Identification of these variables would require proper assignment of an ICD-9/-10-CM code and separate reporting. Thus, it is possible that important thrombotic consequences of SCD during ECLS were not fully appreciated in these analyses.

As the use of ECLS, especially VA ECMO, continues to rise in patients with SCD, our study offers promising insights into its feasibility while highlighting areas of focus for further research to improve our understanding of extracorporeal therapy in this population. One notable observation that warrants investigation is the low VA ECMO survival rate, despite young median age, for those with SCD (27%) compared with the general adult ELSO registry cohort (44%) and those with SCT (42.3%; data not shown). Upon in-depth review of available hemodynamic variables in ELSO, only 12 patients (11 VA ECMO and 1 VV ECMO) had obtainable pulmonary artery catheter data before ECMO initiation. Ten of 12 patients had elevated mean pulmonary artery pressures >20 mm Hg; none of them survived (data not shown). Thus, high VA ECMO mortality in adult SCD cohorts may be, at least in part, secondary to increased risk of death conferred by presence of SCD-related comorbidities, such as pulmonary hypertension.28,29 It also is possible that patients with other common SCD-related conditions such as ACS who required VA ECMO did not have extracorporeal support initiated until they were in an advanced state of decline with development of cardiovascular compromise in addition to pulmonary failure. Within the VA ECMO SCD cohort, 28 of 126 patients (22.2%) had a definitive diagnosis of ACS. In comparison, 35 of 80 patients (43.8%) of the SCD VV ECMO cohort had an ACS diagnosis and they had a higher survival vs those with ACS on VA ECMO (60% vs 37.5%; P = .10). Thus, indication bias may have had a significant role in the elevated VA ECMO mortality. Going forward, in-depth assessment of etiologies of cardiopulmonary decline, clinical course details, comorbidities, and administered interventions will be critical to uncovering reasons for these key findings. Although not comprehensively captured in the ELSO registry, important characteristics linked to increased mortality in SCD such as genotype, reduced fetal hemoglobin, chronic renal insufficiency, and pulmonary hypertension will be needed to help stratify baseline risk.30

Identification of clinical predictors of survival in patients with SCD before VA ECMO initiation can assist with complex clinical decision-making. Thus, a LASSO regression was performed using available data. This analysis revealed that male sex, increased age, eCPR support, elevated lactate, and pre-ECLS cardiac arrest were strongest indicators of mortality. Pre-ECLS arrest had the greatest prognostic value in this model. This analysis has several limitations. First, there were missing values in the ELSO data set. Some data had to be imputed using a random forest approach, which may have introduced bias. Second, LASSO logistic regression analysis was primarily hypothesis-generating and lacked covariates that may better predict in-hospital mortality in this population (eg, precannulation markers of end-organ function, etiology of cardiopulmonary failure, comorbidities, therapeutic interventions, etc). Although this analytic approach provides several advantages over backward stepwise logistic regression and is an effective tool for minimizing multicollinearity and overfitting, our model was not externally validated. Stronger predictive models in complete data sets are needed to fully evaluate the associations of pre-ECMO characteristics and mortality in patients with SCD. In addition, the future evaluation of other hemoglobinopathies such as thalassemia, or other diseases with asplenia, could offer critical insights that may assist in optimizing management and deepen our understanding of the outcomes of those with SCD and other blood disorders with use of ECMO.

Conclusions

In this multicenter study of adult patients with SCD requiring ECMO, we report trends of use, patient characteristics, and clinical outcomes for those treated with both VA and VV modalities in the ELSO registry. The SCD cohort was young and had notably high mortality with VA ECMO therapy, whereas those on VV ECMO had comparatively better survival. We found that male sex, increased age, eCPR support, elevated lactate, and pre-ECLS arrest were strongest indicators of mortality in individuals on VA ECMO. BTEs were associated with in-hospital mortality with both VA and VV ECMO treatment. The sequelae of SCD pathophysiology that drive the need for ECMO or that interact with mediators of an independent cardiopulmonary disease course during both consideration and management of ECLS require further study. Knowledge of baseline characteristics, chronic conditions, acute complications, and clinical course details including diagnoses and interventions leading up to, and during, ECMO therapy in patients with SCD are critical to a deeper understanding of the effectiveness of extracorporeal modalities in this population.

Acknowledgments

M.T.G. receives research support from the National Institutes of Health (grants R01HL098032, R01HL125886, and UH3HL143192), the US Department of Defense, and Globin Solutions, Inc; and had previously received research support for Bayer Corp.

Authorship

Contribution: A.G., M.T.G., M.P., J.R., R.P.R., and A.S. designed the research, performed data analysis and/or interpretation, and wrote the manuscript; A.G. and R.P.R. acquired the data; L.B., A.S.L., T.M.S., K.W., and B.S.T. performed data interpretation, contributed to the study design modification, and contributed to the manuscript writing, editing, and revision.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

M.T.G. reports consultancy with Synhale Therapeutics; is a coinventor of patents and patent applications directed to the use of recombinant neuroglobin and heme-based molecules as antidotes for CO poisoning, licensed by Globin Solutions, Inc, and is a shareholder, advisor, and director in Globin Solutions; is coinventor on patents directed to the use of nitrite salts in cardiovascular diseases, which were previously licensed to United Therapeutics, and now licensed to Globin Solutions and Hope Pharmaceuticals; is an inventor on an unlicensed patent application directed at the use of nitrite for halogen gas poisoning and smoke inhalation; receives royalties from MedMaster, Inc and McGraw-Hill.

Correspondence: Mark T. Gladwin, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 22 South Greene St, Baltimore, MD 21201; email: mgladwin@som.umaryland.edu.

References

Author notes

A.G. and M.P. contributed equally to this study.

Deidentified individual participant data are available indefinitely at 10.6084/m9.figshare.29184119. The analytic code for least absolute shrinkage and selection operator logistic regression and random forest imputation is also available at https://github.com/mplazak9/ELSO_Sickle_Cell.git.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.