Visual Abstract

TO THE EDITOR:

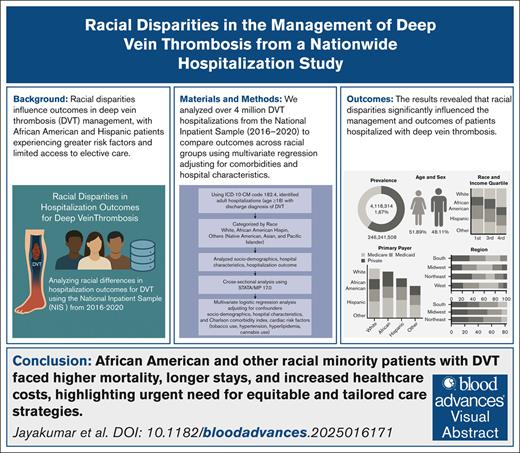

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) refers to the formation of a blood clot in the deep venous system, primarily in the lower extremities.1 It is a leading cause of hospitalization in the United States, with an annual incidence of ∼200 000 cases, of which 50 000 develop pulmonary embolism.2 DVT ranks as the third most common cardiovascular-related cause of death after myocardial infarction and stroke, and often develops after prolonged immobilization.3 Given its increasing incidence and association with various comorbidities, research is focusing on disparities in its management.4

Studies indicate that African American individuals have a higher prevalence of DVT and pulmonary embolism, whereas Asians have a lower risk.5 Genetic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors influence these disparities, with comorbid conditions such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes increasing risk.6 Systemic racism contributes to racial disparities in health care by creating barriers to access, such as lack of insurance, geographic constraints, and limited facilities. These biases in medical treatment influence social determinants of health, like income, education, and housing, leading to delayed diagnoses and suboptimal care.4,6-8

Although previous research has examined DVT incidence and risk factors among racial groups, the impact of race on hospitalization outcomes remains underexplored. This study analyzes racial differences in hospitalization outcomes for DVT using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2016 to 2020, the largest publicly available inpatient health care database in the United States.

Using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification code I82.4, we identified adult hospitalizations (age ≥18 years) with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of DVT. Patients were categorized by race as White, African American, Hispanic, and Others (Native American, Asian, and Pacific Islander). Whites served as the reference group. We analyzed socio-demographics, hospital characteristics, and hospitalization outcomes. A cross-sectional analysis was conducted using STATA/MP 17.0, employing χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables, all identified by International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification codes, with a significance level set at P <.05. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the effect of race on outcomes, adjusting for confounders including socio-demographics, hospital characteristics, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index, and cardiac risk factors (tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cannabis use, and obesity).

Out of 246 241 508 hospitalizations, 4 118 314 had a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of DVT, resulting in a prevalence of 1.67%, compared with previous studies reporting a prevalence of 1.09%.9 The average age was 63.88 years, and 48.11% of the patients were females. Most hospitalizations were among patients who were White, followed by African American, Hispanic, and other racial groups. Over 20% of patients who were African American, Hispanic, and other racial groups were under 65 years, compared with only 15.91% of patients who were White (P < .001). Males represented the majority of DVT cases, except for in patients who were African American (P < .001). African American patients were primarily in the lowest income quartile, associated with worse outcomes, whereas patients who were White were in the second quartile, and other races were in the highest quartile, highlighting the correlation between income disparities and outcomes (P < .001). In the United States, Medicare is a federal program that provides health coverage for people aged ≥65 years, whereas Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that offers health coverage to low-income individuals and families. Most patients across all races were covered by Medicare, with the majority of patients who were African American (25.02%) or Hispanic (20.50%) having Medicaid, and patients who were White (24.59%) or from other racial groups (26.35%) were primarily covered by private insurance (P < .001).

Geographically, most patients who were White or African American were in the South, followed by the Midwest, Northeast, and West, whereas patients who were Hispanic were primarily in the South and West, and other races in the West, aligning with the expected geographic racial distribution in the United States (P = .001). Most patients were treated at urban teaching hospitals with large bed sizes (P = .001) (Table 1).

Patient and hospital-level characteristics of hospitalized adult patients with DVT stratified by race in the NIS (2016-2020)

| Variables . | White (67%), % . | African American (19.31%), % . | Hispanic (8.66%), % . | Others (5.31%), % . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| <65 years | 15.91 | 25.86 | 28.64 | 23.67 | <.001 |

| >65 years | 84.09 | 74.14 | 71.36 | 76.33 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 52.81 | 48.89 | 50.88 | 51.45 | <.001 |

| Female | 47.19 | 51.11 | 49.12 | 48.55 | |

| Median household income national quartiles | |||||

| Quartile 1 (0-25th percentile) | 23.23 | 51.62 | 38.18 | 24.75 | <.001 |

| Quartile 2 (26th-50th percentile) | 26.95 | 20.87 | 25.43 | 20.69 | |

| Quartile 3 (51st-75th percentile) | 26.18 | 16.61 | 22.31 | 23.54 | |

| Quartile 4 (76th-100th percentile) | 23.65 | 10.90 | 14.08 | 31.02 | |

| Insurance type | |||||

| Medicare | 60.63 | 54.09 | 45.94 | 47.85 | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 9.68 | 20.50 | 25.02 | 18.62 | |

| Private | 24.59 | 18.58 | 20.00 | 26.35 | |

| Other | 5.09 | 6.83 | 9.04 | 7.18 | |

| Hospital region | |||||

| Northeast | 19.82 | 17.91 | 16.13 | 24.88 | <.001 |

| Midwest | 25.13 | 21.16 | 7.26 | 11.51 | |

| South | 36.50 | 51.15 | 38.94 | 30.34 | |

| West | 18.55 | 9.78 | 37.67 | 33.27 | |

| Hospital location | |||||

| Rural | 6.79 | 3.04 | 1.46 | 3.00 | <.001 |

| Urban nonteaching | 20.97 | 14.34 | 20.39 | 16.85 | |

| Urban teaching | 72.24 | 82.62 | 78.14 | 80.15 | |

| Hospital bed size | |||||

| Small | 17.59 | 15.86 | 14.82 | 14.50 | <.001 |

| Medium | 26.93 | 26.84 | 27.93 | 25.23 | |

| Large | 55.48 | 57.30 | 57.25 | 60.27 | |

| Variables . | White (67%), % . | African American (19.31%), % . | Hispanic (8.66%), % . | Others (5.31%), % . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| <65 years | 15.91 | 25.86 | 28.64 | 23.67 | <.001 |

| >65 years | 84.09 | 74.14 | 71.36 | 76.33 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 52.81 | 48.89 | 50.88 | 51.45 | <.001 |

| Female | 47.19 | 51.11 | 49.12 | 48.55 | |

| Median household income national quartiles | |||||

| Quartile 1 (0-25th percentile) | 23.23 | 51.62 | 38.18 | 24.75 | <.001 |

| Quartile 2 (26th-50th percentile) | 26.95 | 20.87 | 25.43 | 20.69 | |

| Quartile 3 (51st-75th percentile) | 26.18 | 16.61 | 22.31 | 23.54 | |

| Quartile 4 (76th-100th percentile) | 23.65 | 10.90 | 14.08 | 31.02 | |

| Insurance type | |||||

| Medicare | 60.63 | 54.09 | 45.94 | 47.85 | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 9.68 | 20.50 | 25.02 | 18.62 | |

| Private | 24.59 | 18.58 | 20.00 | 26.35 | |

| Other | 5.09 | 6.83 | 9.04 | 7.18 | |

| Hospital region | |||||

| Northeast | 19.82 | 17.91 | 16.13 | 24.88 | <.001 |

| Midwest | 25.13 | 21.16 | 7.26 | 11.51 | |

| South | 36.50 | 51.15 | 38.94 | 30.34 | |

| West | 18.55 | 9.78 | 37.67 | 33.27 | |

| Hospital location | |||||

| Rural | 6.79 | 3.04 | 1.46 | 3.00 | <.001 |

| Urban nonteaching | 20.97 | 14.34 | 20.39 | 16.85 | |

| Urban teaching | 72.24 | 82.62 | 78.14 | 80.15 | |

| Hospital bed size | |||||

| Small | 17.59 | 15.86 | 14.82 | 14.50 | <.001 |

| Medium | 26.93 | 26.84 | 27.93 | 25.23 | |

| Large | 55.48 | 57.30 | 57.25 | 60.27 | |

Most patients who were Hispanic (51.05%) were discharged home, whereas more patients who were White (51.69%), African American (49.48%), or from other racial groups (47.83%) were discharged to facilities or received home health care (P < .001). Most hospitalizations were nonelective (P < .001), with stays of <1 week, except for other races, who had longer stays (P = .001). Multivariate analysis showed that patients who were African American or Hispanic had lower odds of elective admissions, whereas other races had higher odds. Patients who were African American had higher odds of mortality, whereas patients who were Hispanic had lower odds. African Americans and other racial groups were more likely to require discharge to nursing homes or home health care, and had longer hospital stays with higher charges compared with patients who were White (Table 2).

Racial differences in admission and disposition outcomes, and health care utilization among patients with DVT in the NIS (2016-2020)

| χ2 analysis showing racial differences in admission and disposition outcomes, and health care utilization . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race category . | White (67%), % . | African American (19.31%), % . | Hispanic (8.66%), % . | Others (5.01%), % . | P value . |

| Patient disposition | |||||

| Routine | 43.24 | 45.18 | 51.05 | 44.63 | <.001 |

| Transfer to facility or home health care | 51.69 | 49.48 | 43.94 | 47.83 | |

| Died | 5.07 | 5.34 | 5.01 | 7.53 | |

| Admission type | |||||

| Nonelective | 89.18 | 92.48 | 90.80 | 88.72 | <.001 |

| Elective | 10.82 | 7.52 | 9.20 | 11.28 | |

| Length of stay | |||||

| <7 days | 56.66 | 50.07 | 52.10 | 49.33 | <.001 |

| >7 days | 43.34 | 49.93 | 47.90 | 50.67 | |

| Multivariate regression analysis of racial differences in admission and disposition outcomes, and health care utilization | |||||

| Variables (%) | Elective vs nonelective admission AOR∗ (95% CI),P value | Facility or home health vs routine AOR∗ (95% CI),P value | Died vs discharge from hospital AOR∗ (95% CI),P value | Length of stay >7 days AOR∗ [95% CI],P value | Total charges β† (95% CI),P value |

| White (67%) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| African American (19.31%) | 0.66 (0.63-0.68), .001 | 1.14 (1.05-1.23), .001 | 1.13 (1.06-1.15), .001 | 1.22 (1.19-1.24), .001 | 8 495 (6 002-10 988), .001 |

| Hispanic (8.66%) | 0.86 (0.82-0.91), .001 | 0.91 (0.81-1.02), .125 | 0.87 (0.81-0.93), .001 | 1.16 (1.13-1.19), .001 | 33 422 (29 104-37 741), .001 |

| Other (5.01%) | 1.06 (1.01-1.14), .05 | 1.48 (1.30-1.69), .001 | 1.03 (0.93-1.14), .474 | 1.16 (1.13-1.19), .001 | 39 418 (33 339-45 497), .001 |

| χ2 analysis showing racial differences in admission and disposition outcomes, and health care utilization . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race category . | White (67%), % . | African American (19.31%), % . | Hispanic (8.66%), % . | Others (5.01%), % . | P value . |

| Patient disposition | |||||

| Routine | 43.24 | 45.18 | 51.05 | 44.63 | <.001 |

| Transfer to facility or home health care | 51.69 | 49.48 | 43.94 | 47.83 | |

| Died | 5.07 | 5.34 | 5.01 | 7.53 | |

| Admission type | |||||

| Nonelective | 89.18 | 92.48 | 90.80 | 88.72 | <.001 |

| Elective | 10.82 | 7.52 | 9.20 | 11.28 | |

| Length of stay | |||||

| <7 days | 56.66 | 50.07 | 52.10 | 49.33 | <.001 |

| >7 days | 43.34 | 49.93 | 47.90 | 50.67 | |

| Multivariate regression analysis of racial differences in admission and disposition outcomes, and health care utilization | |||||

| Variables (%) | Elective vs nonelective admission AOR∗ (95% CI),P value | Facility or home health vs routine AOR∗ (95% CI),P value | Died vs discharge from hospital AOR∗ (95% CI),P value | Length of stay >7 days AOR∗ [95% CI],P value | Total charges β† (95% CI),P value |

| White (67%) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| African American (19.31%) | 0.66 (0.63-0.68), .001 | 1.14 (1.05-1.23), .001 | 1.13 (1.06-1.15), .001 | 1.22 (1.19-1.24), .001 | 8 495 (6 002-10 988), .001 |

| Hispanic (8.66%) | 0.86 (0.82-0.91), .001 | 0.91 (0.81-1.02), .125 | 0.87 (0.81-0.93), .001 | 1.16 (1.13-1.19), .001 | 33 422 (29 104-37 741), .001 |

| Other (5.01%) | 1.06 (1.01-1.14), .05 | 1.48 (1.30-1.69), .001 | 1.03 (0.93-1.14), .474 | 1.16 (1.13-1.19), .001 | 39 418 (33 339-45 497), .001 |

Boldface denotes significance.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio.

AOR (for confounders: sociodemographics, hospital characteristics, the Charlson Comorbidity Index, and other cardiac risk factors, including tobacco abuse, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cannabis use, and obesity).

A beta coefficient in regression analysis represents the change in the dependent variable for each 1-unit increase in an independent variable, holding all other variables constant.

DVT remains a major public health concern, with increased efforts to raise awareness and improve prevention strategies.10 Our findings highlight racial disparities in several aspects of DVT care, emphasizing the need to address health care inequities.

Patients who were African American or Hispanic with DVT were less likely to have elective admissions compared with patients who were White, whereas those from other races had higher odds of elective admission. This aligns with studies showing a decline in nonelective admissions among patients who were White and an increase among patients who were African American, suggesting disparities in care initiation.11 Hence, patients who were African American or Hispanic potentially received care in more urgent settings, where treatment may be less planned and outcomes less predictable. Elective admissions, which allow for more proactive and planned management, are often associated with better outcomes and less complications.12,13 The higher nonelective admission rates among minorities may reflect delayed recognition of symptoms or delays in seeking care due to barriers such as limited access to health care or lack of insurance.

Minority groups, particularly patients who were African American or from other racial groups, experienced longer hospital stays and higher total charges, possibly due to complex clinical presentations, coexisting conditions, or treatment delays leading to more severe disease manifestations of DVT.14 These disparities may also reflect differences in hospital types, as patients from minority groups are more often treated in underresourced hospitals, contributing to longer hospitalizations.15

Our study also found significant racial differences in mortality rates, with patients who were African American or from other racial groups experiencing higher mortality compared with patients who were Whites. These disparities may be due to differences in disease severity, access to timely treatment, or quality of care. Additionally, patients who were African American or from other racial groups were more likely to be discharged to nursing homes or home health care, indicating more complex medical needs or limited access to at-home care. In contrast, Hispanic patients were more frequently discharged home, possibly reflecting stronger family support or better access to health care.

The geographical distribution of Hispanic patients in the South and West may contribute to these trends, as these regions have diverse health care infrastructures that impact patient outcomes. Moreover, Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries often have fewer options for nursing home care, leading to higher rejection rates compared with privately insured patients.16,17 These findings emphasize the importance of ensuring equitable care after leaving hospital to meet patients’ clinical needs. Recognizing the differences in health outcomes across racial populations is critical for developing more targeted diagnostic and treatment strategies that promote fair and effective care. A standardized approach to management does not account for the unique challenges faced by racial minorities, emphasizing the need for culturally tailored, inclusive health care strategies.

This study has limitations, including the lack of detailed clinical data (eg, medications, laboratory results) in the NIS database, potential coding inaccuracies, and the inability to establish causal relationships. Unmeasured or residual confounders may remain. The findings may be limited to the United States health care system, and caution is needed when extrapolating results to other settings. Additionally, the study is limited to inpatient settings, excluding outpatient management disparities. The retrospective design and the source of administrative data may introduce selection bias, misclassification, and patient duplication. However, the large sample size strengthens reliability and generalizability.

Racial disparities in DVT outcomes persist, with minority populations experiencing higher mortality, longer hospitalizations, and increased health care utilization. Addressing these disparities requires targeted interventions to improve health care access, manage comorbidities, and reduce socioeconomic barriers. Future research should investigate the mechanisms driving these disparities and evaluate strategies to ensure equitable care delivery.

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards and approved by the institutional review board at the Brooklyn Hospital Center on 2 October 2024 (approval number: 2245168-1). Patient consent was not required for this study as it involved the use of deidentified, publicly available data.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the institutional review board and Graduate Medical Education at the Brooklyn Hospital Center for their time and valuable contributions to this study. They also extend special thanks to their Program Director, Viswanath Vasudevan, for the support and resources, without which this research would not have been possible. The authors declare that no funding was received for this research.

Contribution: All authors contributed substantially to the development of this manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Arya Mariam Roy, Division of Medical Oncology, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, 300 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210; email: aryamariam.roy@osumc.edu.

References

Author notes

Data for this study are derived from public domain resources. The findings of these studies are corroborated by data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), which researchers can access through a standard application process and a signed data use agreement. The authors note that they did not receive any special access to the HCUP data used in this study (covering the years 2016-2020). They paid the necessary fee to obtain the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) data, as specified in the HCUP Central Distributor’s fee schedule, which manages purchase requests and data use agreements (DUAs) for all users (https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/centdist.jsp). Researchers wishing to access HCUP databases must complete the online HCUP DUA (https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/dua.jsp) and agree to its terms. Additional details on how to apply for HCUP database purchases are available at (https://www.distributor.hcup-us.ahrq.gov), and the link for the NIS data set can be found at www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.