Visual Abstract

TO THE EDITOR:

Age is a major prognostic factor for survival in lymphoid cancer (LC).1 The International Prognostic Index (IPI) scores and revised international staging system (R-ISS) in LC have become widely accepted as the gold standard for prognostication in newly diagnosed patients and for the selection of patients to enter clinical trials.2-5 These models most often use 3 to 8 binary variables that are assigned according to weighted scores that are derived from their statistical impact on overall survival (OS) and/or progression-free survival in multivariable Cox regression models in medium to large training cohorts.6-12 Typically, continuous numerical variables are dichotomized by an arbitrary cutoff or are derived from receiver operating characteristic curve analyses (eg, age <65 vs ≥65 years; or lactate dehydrogenase levels below vs above upper limit of normal), rather than using the full prognostic potential contained within the entire range of the continuous numerical variable as with MIPI (mantle cell lymphoma [MCL] IPI).10,13 Other prognostic indices, such as that developed for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, group patients into 4 age groups (<40 vs 40-60 vs 60-75 vs >75 years) and have demonstrated better discriminatory ability of the index in younger patients with DLBCL, whereas the age-adjusted IPI deliberately leaves out the age score.14,15 In contrast, the R-ISS for multiple myeloma (MM) does not consider age at all, although it is primarily intended to identify patients who are in need of intensive therapy rather than for prognostication.12 Furthermore, it is important to recognize that many biologic variables, such as cell of origin in DLBCL, are associated with age.16

Although age cutoffs may be appropriate for selecting patients for potentially toxic treatments and extrapolating clinical trial data, it is also worth noting that only about half the patients with MM or DLBCL from real-world cohorts fulfill the eligibility criteria for clinical trials.17,18 Thus, evidence for the efficacy and safety of new treatments is rarely available for older patients and those with comorbidities. Furthermore, age cutoffs are effective in multivariable analyses to discriminate between 2 subgroups and to calibrate prognostic models (ie, best separation of clinical outcome in fairly equally sized subgroups), thus potentially favoring more simplistic variables. However, such distinction does not necessarily improve prognostication for the full age spectrum of a disease population and often oversimplifies the interpretation of a prognosis, especially for outliers and patients close to the cutoff point.14 When using IPIs, a very young patient is likely to receive an unintended discouraging prognosis and vice versa. With limited data available to deliver accurate prognoses for these patients, what do we say to our very young patients with newly diagnosed LC? To overcome this challenge, we investigated the performance of several IPIs in different age decades in this study.

We used the Danish Lymphoid Cancer Research data resource to retrieve information on the age and subtype-specific IPI variables from Danish Quality registers for patients diagnosed with 1 of 8 LCs, namely classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), DLBCL, follicular lymphoma (FL), marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), MCL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL), and MM.19-22 We included patients with lymphoma and MM from 2005 through 2023 and patients with CLL from 2008 through 2023. The date of the last follow-up was 25 October 2024. Patients registered with multiple LCs were assigned to their primary LC. We subsequently calculated subtype-specific IPIs (ie, International Prognostic Score [IPS] for cHL, Revised IPI for DLBCL, FLIPI2 for FL, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma IPI [MALT-IPI] for MZL, MIPI for MCL, CLL-IPI for CLL, IPS system for Waldenström macroglobulinemia [IPSSWM] for LPL, and R-ISS for MM).6-12 IPS was applied regardless of stage. Patients with missing laboratory values were supplemented with biochemical and genetic data closest to and within 30 days of their LC diagnosis (eg, lactate dehydrogenase and immunoglobulin heavy variable [IGHV] gene status).23 We followed patients from the time of diagnosis to death, emigration, or the end of follow-up. The univariable analyses of OS were stratified based on age groups <40 vs 40 to 49 vs 50 to 59 vs 60 to 69 vs 70 to 79 vs ≥80 years and based on subtype-specific IPI risk group. Furthermore, subgroup analyses were performed in each LC subtype (n = 8) for each age group (n = 6). This study was approved by the Danish Health Data Authority and National Ethics Committee (approvals P-2020-561 and 1804410, respectively). According to Danish legislation, register studies do not require written informed consent.

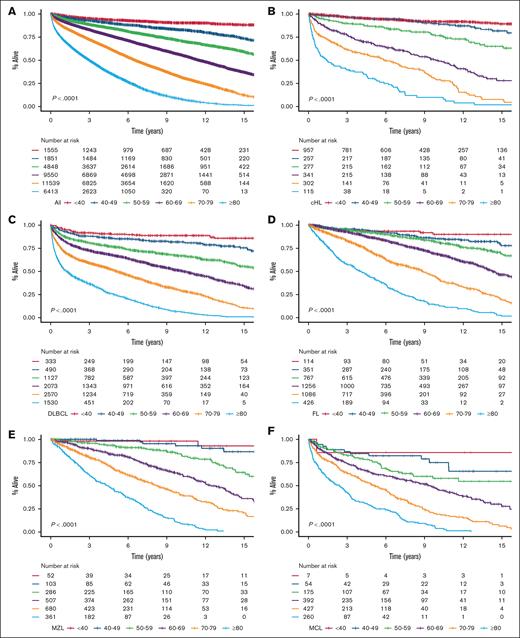

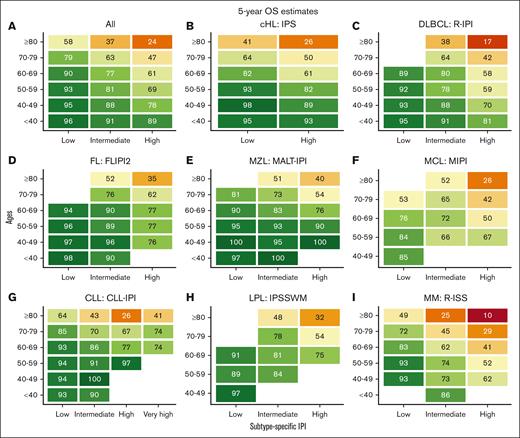

We identified 35 756 Danish patients with newly diagnosed LC (cohort 1), and subtype-specific IPIs could be calculated for 27 532 patients (cohort 2; supplemental Figure 1). The median age for cohort 1 was 70.1 years (interquartile range, 61.0-77.5), and the age distributions for each LC group are provided in supplemental Table 1 and are detailed in supplemental Figure 2. Nearly all high-risk IPI variables were associated with older age, except for lactate dehydrogenase, which likely represents a higher upper limit of normal with older age (supplemental Table 2). When age was used to stratify the entire cohort and each LC cohort separately, there was a correlation between age and OS with older age being associated with shorter OS; however, in the very small group of patients with CLL, those less than 40 years (n = 38) fared worse than expected (Figure 1). Although subtype-specific IPIs contained clear prognostic value (supplemental Figure 3), age intervals as a single prognostic factor stratified patients into a wider survival range (Figure 1 [cohort 1]; supplemental Figure 4 [cohort 2]). In the subgroup analyses of each age group (n = 6) for each LC (n = 8), the subtype-specific IPIs were able to stratify patients, although with lower discrimination capabilities (supplemental Figures 5-12). In these subgroup analyses, subtype-specific IPIs among the more aggressive LCs with more deaths (eg, cHL, DLBCL, and MM) also seemed to separate risk groups better than those for indolent LCs (eg, CLL, FL, and MZL). The subgroup analyses of IPS in advanced stage cHL (ie, stage IIB or higher), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network–IPI in DLBCL, and PRIMA prognostic index in FL are provided in supplemental Figure 13.6,14,24 We subsequently calculated the 5-year OS estimates for each LC group when stratified by age intervals and according to subtype-specific IPI risk for subgroups with more than 10 patients at risk to demonstrate gradual lower 5-year OS rates with both older age and higher risk (Figure 2). Taken together, age alone contains more prognostic value than any IPI but with greater impact on OS for patients with high-risk IPI and vice versa. Thus, these results call for improved prognostication of younger patients.

OS stratified by age intervals. OS in newly diagnosed patients for the entire cohort (A), cHL (B), DLBCL (C), FL (D), MZL (E), MCL (F), CLL (G), LPL (H), and MM (I).

OS stratified by age intervals. OS in newly diagnosed patients for the entire cohort (A), cHL (B), DLBCL (C), FL (D), MZL (E), MCL (F), CLL (G), LPL (H), and MM (I).

Five-year OS estimates stratified by ages and subtype-specific IPI. Five-year OS estimates for newly diagnosed patients for the entire cohort (A), cHL (B), DLBCL (C), FL (D), MZL (E), MCL (F), CLL (G), LPL (H), and MM (I) according to ages and subtype-specific IPI. FLIPI2, follicular lymphoma IPI 2; R-IPI, revised IPI.

Five-year OS estimates stratified by ages and subtype-specific IPI. Five-year OS estimates for newly diagnosed patients for the entire cohort (A), cHL (B), DLBCL (C), FL (D), MZL (E), MCL (F), CLL (G), LPL (H), and MM (I) according to ages and subtype-specific IPI. FLIPI2, follicular lymphoma IPI 2; R-IPI, revised IPI.

Although researchers seem to disagree on a definition of aging, many describe it “simply as an increased chance of dying” and, conversely, perceive death as a function of time.25 In this large population-based, nationwide cohort, the chronological age at the time of diagnosis contained more prognostic information on OS when divided into age brackets than when binary age groups were used that are based on simple cutoffs, and even when compared with subtype-specific IPIs. We therefore believe it would be appropriate to first assess a patient’s age before deciding whether a set of clinical and laboratory biomarkers, such as subtype-specific IPI, may guide the prognosis for survival further. For indolent lymphomas, in particular, the currently recommended IPIs seem to have a lot of room for improvement. Further studies that assess the cause of death for different age groups, along with temporal changes in mortality that are aligned with the implementation of new treatment options, are warranted. This strategy could have a marked impact on the prognosis, especially for the half of patients outside the age interquartile range.

Contribution: C.B. conceived the study, performed the analyses, and wrote the draft manuscript; C.U.N. and C.B. gathered the data; C.B., E.C.R., J.J., S.T., P.d.N.B., and C.U.N. interpreted the data; and all authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.B. reports receiving travel grants from AbbVie outside this study. E.C.R. reports receiving consultancy fees; and travel grants from AbbVie, Janssen, and AstraZeneca outside of this study. J.J. reports receiving travel grants from Roche and AstraZeneca outside this study. S.T. reports receiving honoraria for scientific talks from AbbVie and Thermo Fisher Scientific outside this study. P.d.N.B. reports receiving honoraria from Roche, SERB Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, and Gilead outside this study. C.U.N. reports receiving research funding and/or consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Janssen, AbbVie, BeOne Medicines, Genmab, CSL Behring, Octapharma, Takeda, Eli Lily, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Correspondence: Christian Brieghel, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Blegdamsvej 9, Building 2094, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; email: christian.brieghel@regionh.dk.

References

Author notes

Data may be shared on the Danish Lymphoid Cancer Research data resource based on a data processing agreement. Data may not be shared publicly. The code base is available on GitHub at https://github.com/RH-CLL-LAB/ages.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.