APPs and physicians both perceive APPs as an integral part of the hematology workforce.

APPs and physicians are both interested in best practice guidelines for collaborative care and more APP educational resources in hematology.

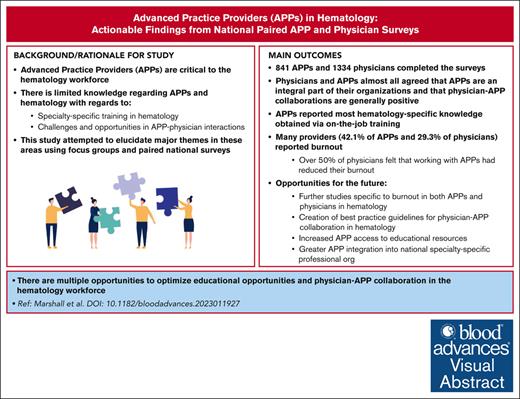

Visual Abstract

Advanced practice providers (APPs) are critical to the hematology workforce. However, there is limited knowledge about APPs in hematology regarding specialty-specific training, scope of practice, challenges and opportunities in APP-physician interactions, and involvement with the American Society of Hematology (ASH). We conducted APP and physician focus groups to elucidate major themes in these areas and used results to inform development of 2 national surveys, 1 for APPs and 1 for physicians who work with APPs. The APP survey was distributed to members of the Advanced Practitioner Society of Hematology and Oncology, and the physician survey was distributed to physician members of ASH. A total of 841 APPs and 1334 physicians completed the surveys. APPs reported most hematology-specific knowledge was obtained via on-the-job training and felt additional APP-focused training would be helpful (as did physicians). Nearly all APPs and physicians agreed that APPs were an integral part of their organizations and that physician-APP collaborations were generally positive. A total of 42.1% of APPs and 29.3% of physicians reported burnout, and >50% of physicians felt that working with APPs had reduced their burnout. Both physicians and APPs reported interest in additional resources including “best practice” guidelines for APP-physician collaboration, APP access to hematology educational resources (both existing and newly developed resources for physicians and trainees), and greater APP integration into national specialty-specific professional organizations including APP-focused sessions at conferences. Professional organizations such as ASH are well positioned to address these areas.

Introduction

The US hematology-oncology workforce is rapidly evolving. Population growth and aging, coupled with a fixed number of training slots in fellowship programs as well as aging and retirement of the existing hematology-oncology workforce, are projected to lead to a significant shortage of practicing hematology-oncology physicians in the near future.1-3 There is particular concern for growing workforce shortages in the field of classical hematology due to low recruitment and retention in this subspecialty.4,5

Optimizing the integration of advanced practice providers (APPs), both nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs), into hematology and oncology clinical care teams is 1 potential way to address the physician workforce shortage. The APP workforce has grown rapidly in the United States over the past 2 decades, and research has shown that APPs conduct up to 25% of all health care visits in some populations.6,7 APPs practice in a wide variety of specialties, and most of their specialty-specific clinical training is on-the-job rather than as part of a formalized educational program. Postgraduate APP fellowships in hematology and hematology-oncology offer APPs the opportunity to receive subspecialty training and prepare for practice specifically in the field of hematology, but to date, relatively few APPs have completed such training.8,9

Physician-APP collaboration may offer several benefits including both the capacity to provide care for a larger number of patients in a broad variety of practice settings as well as potential benefits related to workforce wellness. Inpatient APP-based hematology-oncology services have been described as highly functioning and contributing to reduced workflow fragmentation, with APPs performing multiple clinical care tasks including primary patient care, documentation, and computerized medication order entry.10,11 One recent study demonstrated that higher rates of physician-APP collaboration was associated with reduced physician burnout levels in the community setting.12

Despite the growing number of APPs practicing in both hematology and oncology and prior literature describing the role of APPs in the oncology workforce,13,14 there is little in the published literature regarding either APP or physician perceptions of the APP role and ways to optimize physician-APP collaborations in hematology. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) was interested in exploring these themes further. ASH assembled an APP Engagement Task Force (AATF) comprising 7 ASH physician members and 1 APP collaborator, with the goal of assessing the current status of APP and physician satisfaction with APP practice in hematology as well as the ways that ASH could support improvements in collaborative practice in the future.

Methods

Focus group development and conduction

Members of the AATF worked with researchers from the Mullan Institute to create parallel focus group guides for APPs and physicians about their practice experiences, APP-physician interaction in their organizations, and training/resource needs. The Mullan Institute is a nationally recognized research team focused on how the health workforce contributes to advancing health equity. Its researchers have collaborated with ASH on several prior hematology workforce studies.11,15 In May and June 2022, the Mullan Institute research team conducted a series of 7 focus groups with APPs (49 participants total) and 2 focus groups with physicians (7 participants total). Participants were recruited via email using a contact list generated by the AATF, and focus groups took place virtually via Mullan Institute Zoom accounts. Each focus group met once and was conducted by 2 members of the Mullan Institute research team. No member of the AATF was present during the focus groups.

Survey question development

The members of the AATF and Mullan Institute research team used the results from the focus groups to inform the development of 2 formal surveys, 1 for APPs in hematology and 1 for hematology physicians. The survey of APPs in hematology and oncology contained a total of 46 questions in several areas including demographics, practice experience, APP-physician interaction, job satisfaction, organizational support, burnout, past interactions with ASH, and potential ways that ASH could engage further with APPs. The hematology and oncology physician survey on APP engagement included 36 questions on physician demographics, experiences working with APPs, perceptions of APP-physician interaction and organizational support for APPs, job satisfaction, burnout, and potential ways that ASH could engage further with APPs. The surveys used original items for most domains, but the organizational support questions were derived from previously validated items in the NP primary care organizational climate questionnaire.16 We used a single-item burnout question from the physician work-life survey that has also been previously validated and used in analyses of the hematology-oncology physician workforce.17 The full survey instruments are available in supplemental Documents 1 and 2.

Survey data collection

The survey of APPs in hematology and oncology was distributed to APPs via email through a membership list (n = 3636) provided by the Advanced Practitioner Society for Hematology and Oncology from November to December 2022. The hematology and oncology physician survey on APP engagement was distributed to all ASH member physicians in the United States (n = 7149) via email from October to December 2022. The distribution list for the physician survey included trainees but excluded PhD-only members. For both surveys, the research team sent email reminders to nonrespondents every 2 weeks until the survey closure date. Respondents who completed the full survey received a $10 gift card. Responses were collected virtually using Qualtrics survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT).

Data analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and percentage or frequency distribution for categorical variables) for all variables in the APP and physician surveys. Because responding to each survey question was voluntary, the denominators for these calculations varied depending on the number of respondents who answered each question. We included all usable responses for each question in our analysis.

Results

Demographics and practice settings

The survey of APPs in hematology and oncology received 841 responses (23.1% response rate), and the hematology and oncology physician survey on APP engagement received 1334 responses (response rate, 18.7%).

Respondent demographics and practice setting data for both surveys are presented in Table 1. APP respondents were more likely to be female (93.7% vs 47.3%) and White (77.8% vs 56.2%) than physician respondents. Physician respondents had a slightly higher median age (42 years; range, 24-73 years) than APP respondents (40 years; range, 25-81). Just over half of APPs (52.0%) reported practicing at an academic institution, compared with 77.3% of physician respondents. Most APPs (58.3%) and physicians (54.5%) reported practicing in hematology-oncology for at least 6 years. Among APP survey respondents, 69.5% indicated that they were NPs, 26.4% said they were PAs, and 4.2% said they were other types of APPs.

Survey respondent demographics and practice settings (APPs and physicians)

| Characteristic . | APPs . | Physicians . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | (n = 683) | (n = 979) |

| Median: 40 | Median: 42 | |

| Range: 25-81 | Range: 29-76 | |

| Sex | (n = 741) | (n = 1146) |

| Female | 694 (93.7%) | 542 (47.3%) |

| Male | 42 (5.7%) | 564 (49.2%) |

| Other (prefer to self-describe or prefer not to answer) | 5 (0.7%) | 40 (3.5%) |

| Race (select all that apply) | (n = 742) | (n = 1141) |

| White | 577 (77.8%) | 641 (56.2%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 92 (12.4%) | 295 (25.9%) |

| Black or African American | 37 (5.0%) | 41 (3.6%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 8 (1.1%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| Other | 7 (0.9%) | 27 (2.4%) |

| Ethnicity | (n = 742) | (n = 1141) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 43 (5.8%) | 59 (5.2%) |

| Practice setting | (n = 742) | (n = 1147) |

| Academic institution | 386 (52.0%) | 887 (77.3%) |

| Community practice | 338 (45.6%) | 210 (18.3%) |

| Other | 18 (2.4%) | 50 (4.4%) |

| Years in practice | (n = 744) | (n = 1143) |

| <1 y | 73 (9.8%) | 106 (9.3%) |

| 1-3 y | 130 (17.5%) | 291 (25.5%) |

| 4-5 y | 107 (14.4%) | 123 (10.8%) |

| 6-10 y | 177 (23.8%) | 144 (12.6%) |

| 11-15 y | 97 (13.0%) | 134 (11.7%) |

| >15 y | 160 (21.5%) | 345 (30.2%) |

| Type of APP | (n = 810) | - |

| Nurse practitioner | 582 (71.9%) | - |

| PA | 221 (27.3%) | - |

| Other | 7 (0.9%) |

| Characteristic . | APPs . | Physicians . |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | (n = 683) | (n = 979) |

| Median: 40 | Median: 42 | |

| Range: 25-81 | Range: 29-76 | |

| Sex | (n = 741) | (n = 1146) |

| Female | 694 (93.7%) | 542 (47.3%) |

| Male | 42 (5.7%) | 564 (49.2%) |

| Other (prefer to self-describe or prefer not to answer) | 5 (0.7%) | 40 (3.5%) |

| Race (select all that apply) | (n = 742) | (n = 1141) |

| White | 577 (77.8%) | 641 (56.2%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 92 (12.4%) | 295 (25.9%) |

| Black or African American | 37 (5.0%) | 41 (3.6%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 8 (1.1%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| Other | 7 (0.9%) | 27 (2.4%) |

| Ethnicity | (n = 742) | (n = 1141) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 43 (5.8%) | 59 (5.2%) |

| Practice setting | (n = 742) | (n = 1147) |

| Academic institution | 386 (52.0%) | 887 (77.3%) |

| Community practice | 338 (45.6%) | 210 (18.3%) |

| Other | 18 (2.4%) | 50 (4.4%) |

| Years in practice | (n = 744) | (n = 1143) |

| <1 y | 73 (9.8%) | 106 (9.3%) |

| 1-3 y | 130 (17.5%) | 291 (25.5%) |

| 4-5 y | 107 (14.4%) | 123 (10.8%) |

| 6-10 y | 177 (23.8%) | 144 (12.6%) |

| 11-15 y | 97 (13.0%) | 134 (11.7%) |

| >15 y | 160 (21.5%) | 345 (30.2%) |

| Type of APP | (n = 810) | - |

| Nurse practitioner | 582 (71.9%) | - |

| PA | 221 (27.3%) | - |

| Other | 7 (0.9%) |

APP clinical training

Data regarding APPs’ clinical training are listed in Table 2. APPs reported that they received specialty-specific training relevant to their practice in hematology primarily from on-the-job training (86.5%), independent study (47.4%), and their NP or PA education (42.1%). Only a small number reported receiving specialty-specific education through a fellowship before starting their job (5.0%) or as part of their job (2.6%). Most (76.8%) reported that they needed <6 months training/supervised practice before seeing patients without supervision. Among all the methods queried, APPs were most likely to report using online resources designed for APPs (86.6%), in-person teaching sessions designed for APPs, and in-person or virtual professional meetings (74.3%) to build their hematology specialty-specific expertise. They reported that additional training in several areas would be helpful to them in their current jobs including cytopenias (77.5%), thrombosis/hemostasis (65.3%), lymphoma (65.0%), myeloma and other plasma cell disorders (62.5%), and leukemia (62.1%). When asked which areas they would find useful for building their overall hematology expertise, APPs were most interested in additional training in hemoglobinopathies (51.4%) and stem cell/bone marrow transplantation and cellular therapies (47.0%).

APP education via training and professional development (APP and physician perceptions)

| Educational experience . | APPs . | Physicians∗ . |

|---|---|---|

| Specialty-specific education (select all that apply) | (n = 763) | |

| Onboarding or on-the-job training | 660 (86.5%) | |

| Independent study | 365 (47.8%) | |

| During NP or PA education | 321 (42.1%) | |

| Fellowship before starting job | 38 (5.0%) | |

| Fellowship as part of job | 20 (2.6%) | |

| Other | 72 (9.4%) | |

| Length of training needed | (n = 763) | |

| <6 mo | 586 (76.8%) | |

| 6-12 mo | 129 (16.9%) | |

| 13-24 mo | 24 (3.2%) | |

| >24 mo | 2 (0.3%) | |

| Not sure or still in training | 22 (2.9%) | |

| Professional development resources desired (current job) | ||

| Cytopenias | 77.5% (574/741) | |

| Thrombosis/hemostasis | 65.3% (482/738) | |

| Lymphoma | 65.0% (483/743) | |

| Myeloma and other plasma cell disorders | 62.5% (462/739) | |

| Leukemia | 62.1% (458/738) | |

| Hemoglobinopathies | 41.8% (314/751) | |

| Professional development resources desired (overall expertise) | ||

| Hemoglobinopathies | 51.4% (386/751) | |

| Stem cell/bone marrow transplantation & cellular therapies | 47.0% (347/738) | |

| Thrombosis/hemostasis | 41.3% (305/738) | |

| Lymphoma | 40.1% (298/743) | |

| Myeloma & other plasma cell disorders | 40.1% (296/739) | |

| Leukemia | 39.0% (288/738) | |

| Cytopenias | 36.7% (272/741) | |

| Training tools used by APPs | (n = 763) | (n = 1081) |

| Online resources designed for APPs | 661 (86.6%) | 535 (49.5%) |

| In-person teaching sessions designed for APPs | 583 (76.4%) | 546 (50.5%) |

| In-person or virtual professional meetings | 567 (74.3%) | 649 (60.0%) |

| Online resources designed for physicians | 442 (57.9%) | 364 (33.7%) |

| In-person teaching sessions designed for physicians | 425 (55.7%) | 561 (51.9%) |

| Other | 36 (4.7%) | 42 (3.9%) |

| Don’t know | - | 221 (20.4%) |

| Physician resources desired (% very helpful) | ||

| Working with APPs in outpatient care | 49.6% (521/1057) | |

| Working with APPs in inpatient care | 55.7% (589/1050) | |

| Working with APPs on research projects | 32.8% (343/1047) |

| Educational experience . | APPs . | Physicians∗ . |

|---|---|---|

| Specialty-specific education (select all that apply) | (n = 763) | |

| Onboarding or on-the-job training | 660 (86.5%) | |

| Independent study | 365 (47.8%) | |

| During NP or PA education | 321 (42.1%) | |

| Fellowship before starting job | 38 (5.0%) | |

| Fellowship as part of job | 20 (2.6%) | |

| Other | 72 (9.4%) | |

| Length of training needed | (n = 763) | |

| <6 mo | 586 (76.8%) | |

| 6-12 mo | 129 (16.9%) | |

| 13-24 mo | 24 (3.2%) | |

| >24 mo | 2 (0.3%) | |

| Not sure or still in training | 22 (2.9%) | |

| Professional development resources desired (current job) | ||

| Cytopenias | 77.5% (574/741) | |

| Thrombosis/hemostasis | 65.3% (482/738) | |

| Lymphoma | 65.0% (483/743) | |

| Myeloma and other plasma cell disorders | 62.5% (462/739) | |

| Leukemia | 62.1% (458/738) | |

| Hemoglobinopathies | 41.8% (314/751) | |

| Professional development resources desired (overall expertise) | ||

| Hemoglobinopathies | 51.4% (386/751) | |

| Stem cell/bone marrow transplantation & cellular therapies | 47.0% (347/738) | |

| Thrombosis/hemostasis | 41.3% (305/738) | |

| Lymphoma | 40.1% (298/743) | |

| Myeloma & other plasma cell disorders | 40.1% (296/739) | |

| Leukemia | 39.0% (288/738) | |

| Cytopenias | 36.7% (272/741) | |

| Training tools used by APPs | (n = 763) | (n = 1081) |

| Online resources designed for APPs | 661 (86.6%) | 535 (49.5%) |

| In-person teaching sessions designed for APPs | 583 (76.4%) | 546 (50.5%) |

| In-person or virtual professional meetings | 567 (74.3%) | 649 (60.0%) |

| Online resources designed for physicians | 442 (57.9%) | 364 (33.7%) |

| In-person teaching sessions designed for physicians | 425 (55.7%) | 561 (51.9%) |

| Other | 36 (4.7%) | 42 (3.9%) |

| Don’t know | - | 221 (20.4%) |

| Physician resources desired (% very helpful) | ||

| Working with APPs in outpatient care | 49.6% (521/1057) | |

| Working with APPs in inpatient care | 55.7% (589/1050) | |

| Working with APPs on research projects | 32.8% (343/1047) |

Reporting about APP colleagues.

Physicians reported that APPs with whom they work build hematology-oncology specific knowledge via in-person or virtual professional meetings (60.0%), in-person teaching sessions designed for physicians (51.9%), and in-person teaching sessions (50.5%) and online resources (49.5%) designed for APPs. They felt that additional training for APPs would be helpful to their practices particularly in the areas of cytopenias (67.4% very helpful), leukemia (61.8%), lymphoma (61.6%), thrombosis/hemostasis (59.4%), and stem cell/bone marrow transplant and cellular therapies (56.4%). Physicians felt it would be somewhat or very helpful to have additional training/guidelines for physicians on working with APPs in outpatient care (88.4%), inpatient care (84.5%), and research projects (72.8%).

APP and physician practice patterns

Data regarding APP and physician practice patterns are listed in Table 3. APPs reported spending an average of 77.8% of their time in patient care, split between inpatient (27%) and outpatient (73%) on average. APPs reported providing care in solid tumor oncology (49.0% of time on average), malignant hematology (22.5%), classical hematology (13.1%), and bone marrow/stem cell transplant (8.5%). The most common practice activities reported by APPs included managing their own patient panel (75.5% sometimes or always), conducting/assisting with new patient consults (65.8%), and managing palliative care (64.4%). Of note, we were not able to collect data regarding APPs’ specific scopes of practice and the degree of independence with which they practiced given that such requirements vary widely between different states and different institutions. Just under half of APPs (49.7%) reported being involved in research, most often clinical research (94.4% of those with any research involvement). Most APPs (84.2%) involved in research reported that their research activities were part of their regular job responsibilities.

APP and physician practice patterns

| Characteristic . | APPs . | Physicians . |

|---|---|---|

| Allocation of work hours, mean % | (n = 792) | (n = 1271) |

| Patient care | 77.8% | 55.0% |

| Administration | 11.7% | 9.5% |

| Teaching or training | 6.5% | 8.6% |

| Research | 3.3% | 25.7% |

| Other | 0.7% | 1.2% |

| Allocation of patient care time—clinical areas, mean % | (n = 761) | (n = 1146) |

| Solid tumor oncology | 49.0% | 19.4% |

| Malignant hematology | 22.5% | 32.3% |

| Classical hematology | 13.1% | 30.4% |

| Bone marrow/stem cell transplant | 8.5% | 13.8% |

| Other | 6.9% | 4.1% |

| Allocation of patient care time—settings, mean % | (n=758) | (n=1075) |

| Outpatient | 72.8% | 66.1% |

| Inpatient | 27.0% | 32.9% |

| Other | 0.3% | 1.1% |

| Physician collaboration with APPs | ||

| Work with APPs | - | 90.0% (1114/1238) |

| (If no) want to work with APPs | - | 73.7% (87/118) |

| APP patient care tasks (% sometimes or often)∗ | ||

| Manage own patient panel | 75.5% (566/750) | 57.8% (629/1088) |

| Conduct/assist with new patient consults | 65.7% (494/752) | 54.4% (592/1089) |

| Manage palliative care | 64.4% (483/750) | 57.9% (630/1089) |

| Order routine chemotherapy | 52.1% (390/749) | 48.9% (539/1089) |

| Conduct hospital rounds | 37.7% (282/749) | 67.6% (735/1087) |

| Perform invasive procedures | 32.2% (242/751) | 71.7% (782/1090) |

| Take night or weekend call | 18.4% (138/751) | 31.1% (339/1089) |

| APP research involvement | ||

| Overall (among APPs involved in research) | 49.7% (360/725) | - |

| Clinical research | 94.4% (339/359) | - |

| Health services and outcomes research | 13.1% (47/359) | - |

| Basic science research | 6.7% (24/359) | - |

| Translational research | 6.7% (24/359) | - |

| Public health research | 2.8% (10/359) | - |

| Characteristic . | APPs . | Physicians . |

|---|---|---|

| Allocation of work hours, mean % | (n = 792) | (n = 1271) |

| Patient care | 77.8% | 55.0% |

| Administration | 11.7% | 9.5% |

| Teaching or training | 6.5% | 8.6% |

| Research | 3.3% | 25.7% |

| Other | 0.7% | 1.2% |

| Allocation of patient care time—clinical areas, mean % | (n = 761) | (n = 1146) |

| Solid tumor oncology | 49.0% | 19.4% |

| Malignant hematology | 22.5% | 32.3% |

| Classical hematology | 13.1% | 30.4% |

| Bone marrow/stem cell transplant | 8.5% | 13.8% |

| Other | 6.9% | 4.1% |

| Allocation of patient care time—settings, mean % | (n=758) | (n=1075) |

| Outpatient | 72.8% | 66.1% |

| Inpatient | 27.0% | 32.9% |

| Other | 0.3% | 1.1% |

| Physician collaboration with APPs | ||

| Work with APPs | - | 90.0% (1114/1238) |

| (If no) want to work with APPs | - | 73.7% (87/118) |

| APP patient care tasks (% sometimes or often)∗ | ||

| Manage own patient panel | 75.5% (566/750) | 57.8% (629/1088) |

| Conduct/assist with new patient consults | 65.7% (494/752) | 54.4% (592/1089) |

| Manage palliative care | 64.4% (483/750) | 57.9% (630/1089) |

| Order routine chemotherapy | 52.1% (390/749) | 48.9% (539/1089) |

| Conduct hospital rounds | 37.7% (282/749) | 67.6% (735/1087) |

| Perform invasive procedures | 32.2% (242/751) | 71.7% (782/1090) |

| Take night or weekend call | 18.4% (138/751) | 31.1% (339/1089) |

| APP research involvement | ||

| Overall (among APPs involved in research) | 49.7% (360/725) | - |

| Clinical research | 94.4% (339/359) | - |

| Health services and outcomes research | 13.1% (47/359) | - |

| Basic science research | 6.7% (24/359) | - |

| Translational research | 6.7% (24/359) | - |

| Public health research | 2.8% (10/359) | - |

Data in the “Physicians” column refers to physicians reporting on tasks carried out by APPs.

Physicians reported spending an average of 55.0% of their time in patient care, 25.7% in research, 9.5% in administration, and 8.6% in teaching/training. Physicians reported providing care in solid tumor oncology (19.4% of time on average), malignant hematology (32.3%), classical hematology (30.4%), and bone marrow/stem cell transplant (13.8%). Ninety percent of physicians reported working with APPs in their practice. Physicians who worked with APPs reported that APPs engaged in a variety of clinical activities including procedures (71.8% sometimes or often), conducting hospital rounds (67.6%), managing palliative care (57.9%), and managing their own patient panel (57.8%). Among physicians who reported not working with APPs, 73.7% said they would want to if given the opportunity.

Organizational support, burnout, and practice satisfaction

APP-reported data regarding organizational support, career advancement, burnout, and practice satisfaction are listed in Table 4. Nearly all APPs (96.4%) agreed or strongly agreed that APPs were an integral part of their organizations, and most (85.1%) agreed/strongly agreed that the APP role was well understood by physicians in their organizations. They also reported positive impressions of their interactions with physicians: 96.7% agreed/strongly agreed that physicians trusted their patient care decisions, 93.0% agreed/strongly agreed that they did not need to discuss every patient care detail with a physician, and 88.3% agreed/strongly agreed that they felt valued by their physician colleagues. Although most APPs (93.1%) reported that they freely applied their knowledge and skills to provide patient care, fewer (80.3%) reported that their institutions created an environment in which they could practice at the top of their license. With regard to career development opportunities, APPs reported that they would like further opportunities to pursue leadership roles in administration (56.1%) and leadership roles in education (37.1%).

APP and physician organizational support, career advancement, satisfaction, and burnout

| Characteristic . | APPs . | Physicians . |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational support for APPs (% agree or strongly agree) | ||

| In my organization, the APP role is well understood by physicians | 85.1% (640/752) | 84.6% (885/1047) |

| APPs are an integral part of my organization | 96.4% (725/752) | 94.0% (983/1046) |

| In my organization, APPs freely apply all their knowledge and skills to provide patient care | 93.1% (698/750) | 87.4% (912/1043) |

| My organization creates an environment where APPs can practice at the top of their license | 80.4% (604/752) | 86.3% (898/1041) |

| Trust between APPs and physicians (% agree or strongly agree) | ||

| Physicians in my practice trust my patient care decisions | 96.7% (359/750) | - |

| I trust the patient care decisions of APPs in my practice | - | 87.6% (914/1043) |

| I do not have to discuss every patient care detail with a physician | 92.8% (699/752) | - |

| I do not have to discuss every patient care detail with APPs in my practice | - | 79.7% (831/1043) |

| APPs’ perceptions of collaboration with physicians (% agree or strongly agree) | ||

| I feel valued by my physician colleagues | 88.3% (661/749) | - |

| My organization does not restrict my abilities to practice within my scope of practice | 81.3% (610/751) | - |

| Physicians’ perceptions of collaboration with APPs (% agree or strongly agree) | ||

| Working with APPs improves patient care quality | - | 85.0% (886/1042) |

| Working with APPs improves practice efficiency | - | 92.7% (965/1041) |

| Working with APPs improves my practice satisfaction | - | 86.5% (899/1039) |

| Career advancement opportunities for APPs (select all that apply) | (n = 749) | (n = 1078) |

| Administrative leadership roles (supervisor, etc.) | 420 (56.1%) | 594 (55.1%) |

| Clinical career advancement (promotion to higher level clinical role, etc.) | 311 (41.5%) | 512 (47.5%) |

| Education leadership roles (APP fellowship director, etc.) | 278 (37.1%) | 280 (26.0%) |

| Academic career advancement (assistant professor upward, etc.) | 155 (20.7%) | 163 (15.1%) |

| Other | 15 (2.0%) | 17 (1.6%) |

| None of the above | 209 (27.9%) | 77 (7.1%) |

| Don’t know | 264 (24.5%) | |

| Job and career satisfaction (% satisfied or very satisfied) | ||

| Volume of your patient load/panel size | 76.8% (575/749) | 65.8% (759/1154) |

| Ability to practice to the highest scope of your training | 76.4% (572/749) | - |

| Career development opportunities as an APP in your organization | 50.1% (375/749) | - |

| Relationship with physicians in your organization | 80.7% (603/747) | - |

| Relationship with APPs in your organization | - | 84.3% (878/1041) |

| Quality of care you are able to provide | - | 84.5% (974/1152) |

| Overall satisfaction with your career | 79.8% (597/748) | 82.6% (955/1156) |

| Burnout | (n = 749) | (n = 1155) |

| I enjoy my work. I have no symptoms of burnout. | 74 (9.9%) | 180 (15.6%) |

| Occasionally I am under stress, and I don’t always have as much energy as I once did, but I don’t feel burned out. | 360 (48.1%) | 637 (55.2%) |

| I am definitely burning out and have 1 or more symptoms of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion. | 219 (29.2%) | 240 (20.8%) |

| The symptoms of burnout that I’m experiencing won’t go away. I think about frustration at work a lot. | 63 (8.4%) | 75 (6.5%) |

| I feel completely burned out and often wonder if I can go on. I am at the point where I may need some changes or may need to seek some sort of help. | 33 (4.4%) | 23 (2.0%) |

| Physician ratings of impact of working with APPs on burnout | (n = 1040) | |

| Significant reduced burnout | 199 (19.1%) | |

| Somewhat reduced burnout | 433 (41.6%) | |

| No impact on burnout | 301 (28.9%) | |

| Somewhat increased burnout | 87 (8.4%) | |

| Significantly increased burnout | 20 (1.9%) |

| Characteristic . | APPs . | Physicians . |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational support for APPs (% agree or strongly agree) | ||

| In my organization, the APP role is well understood by physicians | 85.1% (640/752) | 84.6% (885/1047) |

| APPs are an integral part of my organization | 96.4% (725/752) | 94.0% (983/1046) |

| In my organization, APPs freely apply all their knowledge and skills to provide patient care | 93.1% (698/750) | 87.4% (912/1043) |

| My organization creates an environment where APPs can practice at the top of their license | 80.4% (604/752) | 86.3% (898/1041) |

| Trust between APPs and physicians (% agree or strongly agree) | ||

| Physicians in my practice trust my patient care decisions | 96.7% (359/750) | - |

| I trust the patient care decisions of APPs in my practice | - | 87.6% (914/1043) |

| I do not have to discuss every patient care detail with a physician | 92.8% (699/752) | - |

| I do not have to discuss every patient care detail with APPs in my practice | - | 79.7% (831/1043) |

| APPs’ perceptions of collaboration with physicians (% agree or strongly agree) | ||

| I feel valued by my physician colleagues | 88.3% (661/749) | - |

| My organization does not restrict my abilities to practice within my scope of practice | 81.3% (610/751) | - |

| Physicians’ perceptions of collaboration with APPs (% agree or strongly agree) | ||

| Working with APPs improves patient care quality | - | 85.0% (886/1042) |

| Working with APPs improves practice efficiency | - | 92.7% (965/1041) |

| Working with APPs improves my practice satisfaction | - | 86.5% (899/1039) |

| Career advancement opportunities for APPs (select all that apply) | (n = 749) | (n = 1078) |

| Administrative leadership roles (supervisor, etc.) | 420 (56.1%) | 594 (55.1%) |

| Clinical career advancement (promotion to higher level clinical role, etc.) | 311 (41.5%) | 512 (47.5%) |

| Education leadership roles (APP fellowship director, etc.) | 278 (37.1%) | 280 (26.0%) |

| Academic career advancement (assistant professor upward, etc.) | 155 (20.7%) | 163 (15.1%) |

| Other | 15 (2.0%) | 17 (1.6%) |

| None of the above | 209 (27.9%) | 77 (7.1%) |

| Don’t know | 264 (24.5%) | |

| Job and career satisfaction (% satisfied or very satisfied) | ||

| Volume of your patient load/panel size | 76.8% (575/749) | 65.8% (759/1154) |

| Ability to practice to the highest scope of your training | 76.4% (572/749) | - |

| Career development opportunities as an APP in your organization | 50.1% (375/749) | - |

| Relationship with physicians in your organization | 80.7% (603/747) | - |

| Relationship with APPs in your organization | - | 84.3% (878/1041) |

| Quality of care you are able to provide | - | 84.5% (974/1152) |

| Overall satisfaction with your career | 79.8% (597/748) | 82.6% (955/1156) |

| Burnout | (n = 749) | (n = 1155) |

| I enjoy my work. I have no symptoms of burnout. | 74 (9.9%) | 180 (15.6%) |

| Occasionally I am under stress, and I don’t always have as much energy as I once did, but I don’t feel burned out. | 360 (48.1%) | 637 (55.2%) |

| I am definitely burning out and have 1 or more symptoms of burnout, such as physical and emotional exhaustion. | 219 (29.2%) | 240 (20.8%) |

| The symptoms of burnout that I’m experiencing won’t go away. I think about frustration at work a lot. | 63 (8.4%) | 75 (6.5%) |

| I feel completely burned out and often wonder if I can go on. I am at the point where I may need some changes or may need to seek some sort of help. | 33 (4.4%) | 23 (2.0%) |

| Physician ratings of impact of working with APPs on burnout | (n = 1040) | |

| Significant reduced burnout | 199 (19.1%) | |

| Somewhat reduced burnout | 433 (41.6%) | |

| No impact on burnout | 301 (28.9%) | |

| Somewhat increased burnout | 87 (8.4%) | |

| Significantly increased burnout | 20 (1.9%) |

On the 5-point burnout metric, 42.1% of APPs reported experiencing any burnout (scores of 3 or more), and 12.8% reported high levels of burnout (scores of 4 or 5). Despite this, APPs were generally satisfied with their relationships with physicians in their organizations (80.7% very satisfied or satisfied), patient volume (76.8% very satisfied or satisfied), and ability to practice to the highest scope of training (76.4%). They were also highly satisfied with their overall careers (79.8% very satisfied or satisfied) but less satisfied with career development opportunities in their organizations (50.1% very satisfied or satisfied). Most APPs (73.6%) reported that they thought they would still be practicing in hematology-oncology 5 years in the future. Among those who anticipated not being in practice in hematology-oncology, the most frequently cited factors that could motivate them to stay were more flexible schedules and improved work/life balance (74.6%) and better salaries (67.4%).

Physician-reported data regarding organizational support for APPs and physician burnout and practice satisfaction are listed in Table 4. Similar to APPs, nearly all physicians (94.0%) agreed or strongly agreed that APPs were an integral part of their organizations, and most (84.5%) agreed/strongly agreed that the APP role was well understood by physicians in their organizations. They were slightly less likely than APPs to agree or strongly agree that they trusted APPs’ patient care decisions (87.6%) and did not need to discuss every patient care detail (79.7%). They were also less likely than APPs to agree or strongly agree that APPs freely applied their knowledge and skills to provide patient care (87.4%) but more likely than APPs to agree or strongly agree (86.3%) that their organizations created an environment in which APPs could practice at the top of their license. Most physicians agreed or strongly agreed that working with APPs improved practice efficiency (92.7%), practice satisfaction (86.5%), and patient care quality (85.0%).

Physicians were less likely than APPs to report experiencing any burnout (29.3%) and high burnout (8.5%). For those who reported working with APPs, many felt that working with APPs had significantly (19.1%) or somewhat (41.6%) reduced their levels of burnout, whereas only a few reported that it had somewhat (8.4%) or significantly (1.9%) increased burnout. Physicians were generally satisfied with relationships with APPs in their organizations (84.3% very satisfied or satisfied), the quality of care they could provide (84.6%), and their overall careers (82.6%). They were slightly less likely than APPs to report being satisfied with their patient volume (65.8% very satisfied or satisfied).

ASH activities and support

Data from APPs and physicians regarding interactions between APPs and ASH are shown in Table 5. Among APPs who indicated actively participating in any ASH activities, the most frequently reported activity by far was using ASH educational resources (62.4%). Smaller numbers indicated that they attended a small ASH meeting (24.4%), attended an ASH annual meeting (20.9%), used ASH as an opportunity to network with colleagues (15.6%), or presented a poster or oral abstract at the annual meeting (2.8%). For those who reported wanting to attend an ASH annual meeting but not being able to, the primary barriers to attendance included clinical coverage issues (47.7%), financial barriers (45.0%), and childcare or other caretaking responsibilities (31.1%). Only a few respondents (5.1%) indicated that ASH verification of professional status regulations were a barrier to their attendance at the annual meeting. APPs reported interest in several resources that ASH could potentially provide to them, including guidelines for APPs and physicians on best practices for collaboration (75.6%), access to new ASH educational resources developed for APPs (68.5%), special sessions at ASH meetings for APPs in clinical practice (65.7%), access to existing ASH educational resources for trainees and practicing physicians (59.1%), an ASH membership option for APPs (57.0%), and ASH-sponsored networking opportunities for APPs (54.0%). Fewer APPs reported a wish to participate on ASH committees (24.6%) or register for the ASH annual meeting without verification of professional status (21.7%), which is currently a requirement for registration.

APP interactions and opportunities within ASH (APP and physician perceptions)

| Activity/offering . | APPs∗ . | Physicians . |

|---|---|---|

| ASH-related activity participation by APPs (select all that apply) | (n = 431) | (n = 953) |

| Used ASH educational resources | 269 (62.4%) | 215 (22.6%) |

| Attended a small ASH meeting | 105 (24.4%) | 126 (13.2%) |

| Attended an ASH annual meeting | 90 (20.9%) | 269 (28.2%) |

| Used ASH as an opportunity to network with colleagues | 67 (15.6%) | 132 (13.9%) |

| Presented a poster or oral abstract at ASH annual meeting | 12 (2.8%) | 122 (12.8%) |

| Other | 63 (14.6%) | 35 (3.7%) |

| Don’t know | - | 510 (53.5%) |

| ASH offerings desired for APPs (select all that apply) | (n = 702) | (n = 1137) |

| Guidelines for APPs & MDs on best practices for APP/MD collaboration in hematology/oncology | 531 (75.6%) | 704 (61.9%) |

| Access to new ASH educational resources developed specifically with APPs in mind | 481 (68.5%) | 781 (68.7%) |

| Special sessions at ASH meetings for APPs in clinical practice | 461 (65.7%) | 709 (62.4%) |

| Access to existing ASH educational resources developed for residents/fellows/practicing physicians | 415 (59.1%) | 751 (66.1%) |

| ASH membership option (does not require doctoral degree) | 400 (57.0%) | 701 (61.7%) |

| Networking opportunities for APPs sponsored by ASH | 379 (54.0%) | 618 (54.4%) |

| Opportunity to participate on ASH committees | 173 (24.6%) | 436 (38.4%) |

| Opportunity to register for ASH annual meeting without verification of professional status | 152 (21.7%) | 568 (50.0%) |

| Other | 15 (2.1%) | 16 (1.4%) |

| Activity/offering . | APPs∗ . | Physicians . |

|---|---|---|

| ASH-related activity participation by APPs (select all that apply) | (n = 431) | (n = 953) |

| Used ASH educational resources | 269 (62.4%) | 215 (22.6%) |

| Attended a small ASH meeting | 105 (24.4%) | 126 (13.2%) |

| Attended an ASH annual meeting | 90 (20.9%) | 269 (28.2%) |

| Used ASH as an opportunity to network with colleagues | 67 (15.6%) | 132 (13.9%) |

| Presented a poster or oral abstract at ASH annual meeting | 12 (2.8%) | 122 (12.8%) |

| Other | 63 (14.6%) | 35 (3.7%) |

| Don’t know | - | 510 (53.5%) |

| ASH offerings desired for APPs (select all that apply) | (n = 702) | (n = 1137) |

| Guidelines for APPs & MDs on best practices for APP/MD collaboration in hematology/oncology | 531 (75.6%) | 704 (61.9%) |

| Access to new ASH educational resources developed specifically with APPs in mind | 481 (68.5%) | 781 (68.7%) |

| Special sessions at ASH meetings for APPs in clinical practice | 461 (65.7%) | 709 (62.4%) |

| Access to existing ASH educational resources developed for residents/fellows/practicing physicians | 415 (59.1%) | 751 (66.1%) |

| ASH membership option (does not require doctoral degree) | 400 (57.0%) | 701 (61.7%) |

| Networking opportunities for APPs sponsored by ASH | 379 (54.0%) | 618 (54.4%) |

| Opportunity to participate on ASH committees | 173 (24.6%) | 436 (38.4%) |

| Opportunity to register for ASH annual meeting without verification of professional status | 152 (21.7%) | 568 (50.0%) |

| Other | 15 (2.1%) | 16 (1.4%) |

Includes only APPs who indicated any ASH participation.

Among physicians who reported on the ASH activity participation of the APPs they work with, more than half (53.5%) said they did not know whether their APP colleagues had participated in ASH activities. The most frequently identified ASH activities identified by physicians (able to answer the question about participation by APPs with whom they worked) were attending an annual meeting (28.2%), using ASH educational resources (22.6%), using ASH as a networking opportunity (13.9%), and attending a small ASH meeting (13.2%). When asked about opportunities and resources ASH could potentially provide for APPs, physicians reported interest in access to new ASH educational resources developed for APPs (68.7%), access to existing ASH educational resources for trainees and practicing physicians (66.1%), special sessions at ASH meetings for APPs in clinical practice (62.4%), guidelines for APPs and physicians on best practices for collaboration (61.9%), and an ASH membership option that does not require verification of professional status (61.7%).

Discussion

In this focus group–informed national survey of both APPs practicing in hematology and oncology and hematology-oncology physicians, we found that both types of providers generally reported positive interactions working with members of the other provider group. We identified opportunities for clinical education/training as well as physician-APP collaboration that could be enacted both at the institutional level as well as at the national society level. Additionally, both APPs and physicians reported relatively high rates of burnout, but most physicians thought that collaborating with APPs was helpful in mitigating physician burnout.

With regard to APP-physician interactions, we found that APPs and physicians both perceived APPs as integral to their organizations. Although APPs were slightly less likely than physicians to feel that they freely applied their knowledge/skills and practiced at the top of the scope of their license, both groups agreed with these statements ∼80% of the time, indicating an overall positive dynamic of interprovider trust and satisfaction with organizational support but with room for improvement. Prior research in radiation oncology has also demonstrated both APP and physician interest in increased clinical roles with increased autonomy for APPs.18 Institutions, and individual departments within institutions, could work with both APPs and physicians to develop pathways to allow for APPs to practice at the top of their licenses to optimize utilization in clinical practice. This may offer an opportunity to increase patient access and improve patient satisfaction via APP-led clinical activities such as triage and follow-up telephone calls.19,20 Additionally, past research has shown high provider satisfaction and improved access to care with electronic consultation models in hematology, particularly classical hematology.21-24 APP-led electronic consult services for frequent and relatively simple conditions such as management of iron deficiency anemia and perioperative anticoagulation management may offer improved patient/provider access to subspecialty care in hematology and also allow for hematology physicians to focus on more complex cases that require a higher level of care.

One area that stood out in terms of low APP satisfaction was career development. Although most APPs reported high satisfaction with their overall careers and a desire to continue practicing in the field of hematology and oncology over time, only 50% were satisfied with career development opportunities within their organizations. This is an important finding for individual health systems as well as national organizations looking to improve retention within a given specialty. We see opportunities for APP education, both in the clinical sphere as well as in the areas of leadership and mentorship, as a tool to improve career development. Clinical education in hematology most often takes place as on-the-job training, and APPs were interested in additional training in several subspecialty areas of hematology. Creation of APP-specific training materials (or modification of existing physician resources to be more APP specific) may be a good initial step in preparing APPs to practice in these roles. Few APPs currently report participating in hematology-specific fellowships before employment in the hematology workforce, and such fellowships could be expanded as a tool to generate a “pipeline” of trained APPs. This strategy may help both to optimize practice at the top of license and also reduce organizational costs and onboarding times.25,26 Fellowships also offer an opportunity for APP leadership training, which may improve APP career development opportunities and improve satisfaction in this sphere.27 The recent ability of subspecialty APP fellowships to seek accreditation may improve recognition and recruitment to these additional educational programs.28 Development of “career ladders” and pathways to specialty-specific APP leadership positions in hematology and oncology may also offer the career development opportunities that APPs are looking for and help improve workforce retention.

We also found that >40% of APPs and ∼30% of physicians reported burnout. Prior data in the APP population in hematology and oncology has demonstrated burnout rates ranging from ∼30% in nurse practitioners to as high as 49% in PAs.29,30 Although the methods for assessing burnout and the populations evaluated differs between studies, our observed rate of 40% seems in keeping with prior data. Additionally, the 2 prior studies each had between 200 to 300 respondents, and our sample size of >800 adds to the literature in this area. The physician burnout rate we observed is somewhat lower than that seen in the most recent prior studies conducted among the hematology physician and oncology physician workforces (37% and 45%, respectively) as well as in the general physician population in the United States (38%). This could be due to several factors including different burnout assessment methodology, percentage of physicians in academic practice (>70% in our study compared with <40% in the prior studies in hematology and oncology), and a variety of other factors not explicitly explored within the context of the study.11,31,32 Interestingly, ∼60% of physicians in our study generally felt that working with APPs had reduced their burnout levels. Combined with initial data that physicians in community practice reported lower levels of burnout when using APPs to a higher degree,11 these data suggest potential reasons to expand APP utilization in a variety of clinical settings. Optimization of physician-APP interactions may be not only a way to improve clinical practice, but also a potential way to improve physician well-being. Future studies focused on the impact of positive physician-APP interactions on burnout among APPs could help identify specific collaborative approaches that reduce burnout, ideally for both physicians and APPs.

Regarding interactions with ASH specifically, over half of APPs reported making use of existing ASH educational resources but less than 1 quarter reported attending the ASH annual meeting, citing barriers such as need to remain behind to cover clinical as well as financial and childcare issues. Very few APPs reported using ASH to network or to present research. Interestingly, although physicians often work closely with APPs, over half did not know about whether their APP colleagues participated in ASH activities at all, pointing to both an existing lack of communication and also an opportunity for improved group discussion within institutions and organizations about how to best use professional resources to maximize professional development for all. APPs and physicians were both interested in increased opportunities for APP interaction with ASH (both expanded access to existing resources for physicians as well as creation of new APP-specific resources) and APP membership opportunities. Finally, over half of both groups felt that guidelines for physician-APP collaboration would be useful, clearly pointing to an opportunity for ASH to develop such guidelines in the future. Team-based care is essential to the practice of hematology, and guidelines on team-based care in oncology provide a framework for developing similar resources for APPs and physicians specializing in hematology.33 The AATF feels that ASH would benefit from developing a series of best practice guidelines for APP-physician collaboration in hematology as well as guidelines and resources for onboarding and training of APPs new to the field of hematology.

A major strength of this study was the inclusion of input from both APPs and physicians and our ability to directly compare responses between both groups due to the similarity of the survey instruments. Although 1 limitation was the relatively low response rate (23% APP and 19% physician), we feel that with >800 APP responses (to our knowledge making this the largest hematology-focused study of APPs to date) and >1000 physician responses there is feasible generalizability to the APP and physician hematology workforce as a whole. The recent ASH-led survey regarding burnout in hematologists and the impact of APP support had a response rate of 25%, relatively similar to the response rate in this study.11 We also note that scope of practice and degree of independent practice may vary among respondents based on the state and institution of practice. Future studies could specifically explore the relationships between the degree of independent practice and APP/physician burnout and satisfaction with collaborative practice. In addition, we note that there were disparities in the percentage of APP vs physician respondents practicing in academic institutions (52% APPs vs 77% of physician respondents), which may somewhat limit the ability to compare responses across practice settings without additional subgroup analysis. Another observation we note is the variety of responses regarding physician-APP pairings, with 44.3% of respondents reporting working with 1 to 2 APPs, 31.5% with 3 to 5, and 21.8% with >5. Neither this study nor others in the literature have examined the differences in practice efficiency and satisfaction based on the number of APPs who work with an individual physician or the ideal “team” setup with regard to APP-physician pairings. Lastly, we note that survey respondents were all members of professional specialty groups (physicians were ASH members, and APPs were Advanced Practitioner Society for Hematology and Oncology members), so, the responses may differ between specialty group members and physicians or APPs who are not members of these professional societies with regard to workplace setting, educational experiences, physician-APP collaboration patterns, and other aspects of the physician-APP relationship. Future studies could focus on the hematology workforce at large with expansion beyond the framework of individual professional societies.

APPs are an essential part of the growing and evolving hematology workforce in the United States. Our survey provides support for further collaboration with APPs in hematology because the role of APPs will only expand and solidify in the future due to increased clinical needs and patient volumes. We have identified opportunities for both individual institutions as well as national societies to expand educational opportunities and career development opportunities for APPs in hematology. A systems-based approach has the potential for positive impact on our specialty.34,35 The AATF believes the integration of APPs into hematology practice, and the utilization of APPs at the top of their scope of license offers a way to further optimize clinical care of patients with hematologic disorders as well as a potential ways to reduce burnout in the hematology physician workforce.11,36 Future investigations could examine optimal team configurations for different types of hematology care, the role of APP-physician collaboration on burnout in APPs, and patient satisfaction with APP interactions in hematology, because our ultimate goal should be to sustain a compassionate and effective workforce for all patients and providers in hematology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the American Society of Hematology for supporting the creation and ongoing work of the APP Task Force. In particular, the authors acknowledge the contributions of Gina Moses and Robby Reynolds, whose contributions were instrumental to the Task Force and the survey. The authors also thank the leaders of the Advanced Practitioner Society for Hematology and Oncology for collaborating on the survey distribution.

Authorship

Contribution: A.L.M. chaired the AATF, developed the survey tool, wrote the introduction and discussion sections of the manuscript, and critically reviewed the Methods and Results sections; L.E.M. contributed to the AATF, developed the survey tool, conducted the focus groups, oversaw distribution and administration of the surveys, performed the data analysis, wrote the methods and results sections, and critically reviewed the Introduction and Discussion sections; P.A.K., F.E.D., A.F., S.N., and A.H. contributed to the AATF, developed the survey tool, and critically reviewed the entire manuscript; R.B. developed the survey tool and critically reviewed the entire manuscript; C.E.E. contributed to the AATF, developed the survey tool, conducted the focus groups, oversaw distribution and administration of the surveys, and critically reviewed the entire manuscript; and all authors have reviewed the manuscript in final form and consent to submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ariela L. Marshall, Division of Hematology, Oncology, and Transplantation, University of Minnesota, 420 Delaware St SE, MMC 480, Minneapolis, MN 55455; email: mars2207@umn.edu.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Ariela L. Marshall (mars2207@umn.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.