Over the past decade, T-cell–directed therapies, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) and bispecific T-cell engager (BTE) therapies, have reshaped the treatment of an expanding number of hematologic malignancies, whereas tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, a recently approved cellular therapy, targets solid tumor malignancies. Emerging data suggest that these therapies may be associated with a high incidence of serious cardiovascular toxicities, including atrial fibrillation, heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, and other cardiovascular toxicities. The development of these events is a major limitation to long-term survival after these treatments. This review examines the current state of evidence, including reported incidence rates, risk factors, mechanisms, and management strategies of cardiovascular toxicities after treatment with these novel therapies. We specifically focus on CAR-T and BTE therapies and their relation to arrhythmia, heart failure, myocarditis, bleeding, and other major cardiovascular events. Beyond the relationship between cytokine release syndrome and cardiotoxicity, we describe other potential mechanisms and highlight key unanswered questions and future directions of research.

Introduction

Over the last decade, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy and bispecific T-cell engagers (BTEs) have revolutionized the treatment of hematologic malignancies.1-10 Commercially available CAR-Ts are ex vivo modified T cells that are engineered to target a specific tumor antigen such as CD19 in B-cell malignancies or B-cell maturation antigen in multiple myeloma.11 BTE cell therapy is a shorter acting T-cell therapy in which a dual-target antibody is designed to bind on 1 end to the T-cell receptor component CD3 and on the other to tumor antigens.12 Both CAR-T and BTE therapies are primarily used to treat hematologic malignancies, however, several ongoing CAR-T products are being investigated in early phase clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumors. Although their mechanisms of action differ, T-cell–based therapies all serve 1 goal, to facilitate T-cell attack on and eradicate tumor cells.

There are currently ∼400 registered trials actively recruiting for T-cell–based therapy protocols in the United States alone.13 Understanding their adverse event (AE) profile becomes crucial because these novel cellular therapies expand into widespread use for a growing range of indications. In particular, cardiovascular AEs (CVAEs) have emerged as potentially important drivers of morbidity and mortality after T-cell–based therapy.14,15

Although treatment-related cardiotoxicity is a recognized driver of morbidity and mortality in many cancer types,16-19 several considerations make T-cell–based therapies of special importance. First, these therapies are increasingly being administered to older patients who may have preexisting cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, or a combination thereof, increasing their susceptibility to cardiotoxicity.20-23 Second, they are often used in the relapsed/refractory setting, in which patients may have already received anthracyclines or other cardiotoxic chemotherapies that compound cardiac risk.24 Finally, lymphodepletion regimens required before CAR-T therapy often incorporate agents that have known cardiotoxic potential.25

To establish best practices regarding cardiovascular care for patients receiving novel cellular immunotherapies, we aim to comprehensively review the existing evidence on cardiotoxicity associated with CAR-T and BTE treatment(s). Our goal is to synthesize current knowledge and provide clinically relevant guidance surrounding the cardiovascular safety of these emerging therapies.

Possible mechanisms for cellular therapy–associated cardiotoxicities

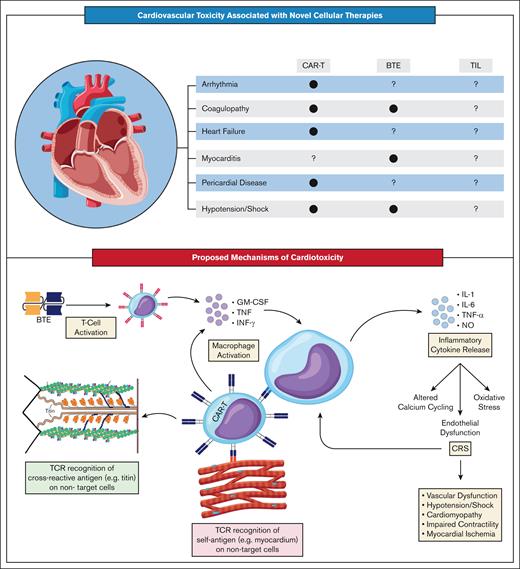

Although the exact mechanisms underlying the cardiotoxic effects of T-cell therapies remain poorly defined, theories have coalesced around 3 main pathways (Figure 1).26,27 The first proposes that cardiotoxicity arises indirectly through on-target inflammatory effects on the tumor microenvironment. These effects trigger the systemic release of proinflammatory cytokines, leading to cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and subsequent cardiac dysfunction. The second theory suggests T cells directly engage antigens shared between tumor and cardiac tissue, eliciting targeted toxicity. Finally, some evidence indicates T cells may also attack the heart via off-target interactions with myocardial antigens unrelated to tumor tissue. It is important to note that most mechanistic data described so far focus specifically on CAR-T therapy. Comparatively, less is known about the mechanisms of cardiotoxicity associated with BTE.

Cardiovascular toxicity associated with cellular therapies. (A) Current literature has identified several cardiotoxic side effects of CAR-Ts, including arrhythmia, coagulopathy, heart failure, pericardial disease, and hypotension/shock. Less is known about the cardiotoxicity of BTEs, with only coagulopathy myocarditis, and hypotension/shock having been associated with therapy. Finally, there has been no definitive association between cardiotoxicity and TILs, given their recent introduction. (B) The mechanism of cardiotoxicity associated with cellular therapies can be divided into 3 categories: CRS-mediated cardiovascular dysfunction, direct cardiotoxicity, and indirect cardiotoxicity. Activated CAR-Ts or BTEs release cytokines, including granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interferon gamma (IFN-γ), which lead to macrophage activation, resulting in a proinflammatory cascade that causes oxidative stress, altered calcium cycling, and endothelial dysfunction, ultimately resulting in cardiovascular dysfunction. Indirect cardiotoxicity has been documented with CAR-Ts, in which engineered cells attack the sarcomeric protein titin as a crossantigen. Direct cardiotoxicity has been proposed as an alternative pathway in which CAR-Ts directly attack the myocardium. NO, nitric oxide.

Cardiovascular toxicity associated with cellular therapies. (A) Current literature has identified several cardiotoxic side effects of CAR-Ts, including arrhythmia, coagulopathy, heart failure, pericardial disease, and hypotension/shock. Less is known about the cardiotoxicity of BTEs, with only coagulopathy myocarditis, and hypotension/shock having been associated with therapy. Finally, there has been no definitive association between cardiotoxicity and TILs, given their recent introduction. (B) The mechanism of cardiotoxicity associated with cellular therapies can be divided into 3 categories: CRS-mediated cardiovascular dysfunction, direct cardiotoxicity, and indirect cardiotoxicity. Activated CAR-Ts or BTEs release cytokines, including granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interferon gamma (IFN-γ), which lead to macrophage activation, resulting in a proinflammatory cascade that causes oxidative stress, altered calcium cycling, and endothelial dysfunction, ultimately resulting in cardiovascular dysfunction. Indirect cardiotoxicity has been documented with CAR-Ts, in which engineered cells attack the sarcomeric protein titin as a crossantigen. Direct cardiotoxicity has been proposed as an alternative pathway in which CAR-Ts directly attack the myocardium. NO, nitric oxide.

Role of CRS in cardiotoxicity susceptibility

CRS has traditionally been considered the key driver of cardiovascular toxicity associated with cellular therapies. Characterized by fever and hypotension, it is a common side effect of CAR-T and BTE therapies.28,29 A substantial proportion of patients treated with CAR-T in the landmark clinical trials developed CRS, and the incidence varies based on the type of CAR-T construct (CD28 vs 4-1-BB costimulatory molecules), as well as the underlying disease and tumor burden. The rate of CRS ranges from 77% to 92% in acute leukemia trials1,30 39% to 94% in B-cell lymphoma trials3,31-38 and up to 95% in multiple myeloma trials4,5,39,40 (Table 1). Notably, recent trials have reported up to a 76% incidence of CRS even with non-CD28 constructs,5,41,42 suggesting insidious associated events such as arrhythmia may still be not well defined.

CVAEs reported in landmark clinical trials evaluating cellular therapies

| Study . | Trial name|| . | Study phase . | Drug class . | Drug name . | Indication . | Intervention arm sample size . | Median follow-up duration, mo∗ . | Rate of CRS† . | Rate of treatment-emergent CVAEs . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmia‡ . | Hypertension . | Coagulopathy§ . | Others . | |||||||||

| Maude et al1,43 | ELIANA | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Tisagenlecleucel | R/R preB-ALL | 79 | 13.1 | 61 (77%) | 2 (4%) | 145 (19%) | 5 (6%) | Cardiac failure, 10 (9%) |

| Schuster et al32,43 | JULIET | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Tisagenlecleucel | R/R DLBCL | 115 | 28.6 | 85 (74%) | 12 (10%) | 5 (4%) | 5 (4%) | Cardiac failure, 1 (1%) |

| Fowler et al35,43 | ELARA | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Tisagenlecleucel | R/R FL | 97 | 16.6 | 51 (53%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (5%) | 2 (2%) | NA |

| Neelapu et al31,44 | ZUMA-1 | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Axicabtagene ciloleucel | R/R LBCL | 108 | 8.7 | 101 (94%) | 25 (23%) | 16 (15%) | 2 (2%) | Cardiac failure, 6 (6%) Cardiac arrest, 4 (4%) |

| Jacobson et al36,44 | ZUMA-5 | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Axicabtagene ciloleucel | R/R iNHL | 146 | 17.5 | 123 (84%) | 31 (21%) | 19 (13%) | 9 (6%) | Cardiac failure, 3 (2%) |

| Locke et al44,45 | ZUMA-7 | Phase 3 | CAR-T | Axicabtagene ciloleucel | R/R LBCL | 168 | 24.9 | 155 (92%) | 24 (14%) | 15 (9%) | 15 (9%) | Cardiac failure, 2 (1%) |

| Wang et al33,46 | ZUMA-2 | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Brexucabtagene autoleucel | R/R MCL | 82 | 12.3 | 75 (91%) | 8 (10%)¶ | 15 (18%) | 8 (10%) | NA |

| Shah et al30,46 | ZUMA-3 | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Brexucabtagene autoleucel | R/R preB-ALL | 78 | 16.4 | 72 (92%) | 12 (15%) | 10 (13%) | 13 (17%) | Cardiac failure, 3 (4%) |

| Kamdar et al3,47 | TRANSFORM | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Lisocabtagene maraleucel | R/R LBCL | 89 | 6.2 | 44 (49%) | 13 (15%)# | 6 (7%) | NA | NA |

| Sehgal et al38,47 | PILOT | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Lisocabtagene maraleucel | R/R LBCL | 61 | 12.3 | 24 (39%) | 6 (10%)# | 6 (10%) | NA | NA |

| Abramson et al34,47 | TRANSCEND | Phase 1 | CAR-T | Lisocabtagene maraleucel | R/R LBCL | 268 | 18.8 | 123 (46%) | 16 (6%) | 38 (14%) | NA | Cardiomyopathy 4 (1.5%) |

| Siddiqi et al48 | TRANSCEND CLL | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Lisocabtagene maraleucel | R/RCLL | 117 | 21.1 | 99 (85%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Munshi et al4,49 | KarMMa | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Idecabtagene vicleucel | R/R MM | 127 | 13.3 | 108 (85%) | 6 (4.7%) | 14 (11%) | 11 (9%) | Cardiomyopathy 2 (1.6%) |

| Rodriguez-Otero et al49,50 | KarMMa-3 | Phase 3 | CAR-T | Idecabtagene vicleucel | R/R MM | 222 | 18.8 | 202 (91%) | 16 (7%) | 31 (14%) | 31 (14%) | NA |

| Berdeja et al39,51 | CARTITUDE-1 | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel | R/R MM | 97 | 12.4 | 92 (95%) | 8 (8%) | 18 (19%) | 21 (22%) | NA |

| Cohen et al40 | CARTITUDE-2 | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel | R/R MM | 20 | 11.3 | 12 (60%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| San-Miguel et al5,51 | CARTITUDE-4 | Phase 3 | CAR-T | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel | R/R MM | 188 | 15.9 | 147 (78%) | 6 (3%) | 13 (7%) | 9 (5%) | NA |

| Kantarjian et al6,52 | TOWER | Phase 3 | BTE | Blinatumomab | R/R preB-ALL | 267 | 11.7 | 38 (14.2%) | NA | 17 (6.4%) | NA | AMI, 1 (0.4%) Cardiac arrest, 1 (0.4%) Cardiac failure, 1 (0.4%) Pericardial effusion, 1 (0.4%) |

| Locatelli et al52,53 | RIALTO | Phase 3 | BTE | Blinatumomab | R/R preB-ALL | 110 | 17.4 | 18 (16.4%)∗∗ | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Martinelli et al54 | ALCANTARA | Phase 2 | BTE | Blinatumomab | R/R preB-ALL | 45 | 16.1 | 4 (9%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gökbuget et al55 | BLAST | Phase 2 | BTE | Blinatumomab | MRD positive preB-ALL | 116 | 30 | 4 (3%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Moreau et al7,56 | MajesTEC-1 | Phase 2 | BTE | Teclistamab | R/R MM | 165 | 14.1 | 119 (72%) | 26 (16%) | 20 (12%) | NA | NA |

| Dickinson et al8,57 | NP30179 | Phase 2 | BTE | Glofitamab | R/R DLBCL | 154 | 12.6 | 102 (66%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Budde et al9,58 | GO29781 | Phase 1 | BTE | Mosunetuzumab | R/R FL | 90 | 12.6 | 40 (44%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Thieblemont et al10,59 | EPCORE NHL-1 | Phase 1/2 | BTE | Epcoritamab | R/R LBCL | 157 | 10.7 | 80 (51%) | 16 (10%) | NA | NA | AMI, 1 (0.6%) |

| Chesney et al60,61 | C-144–01 | Phase 2 | TIL | Lifileucel | Unresectable/metastatic melanoma | 156 | 27.6 | 5 (3.2%) | 74 (47.4%)# | 21 (13.5%) | NA | Hypotension, 52 (33.3%) |

| Study . | Trial name|| . | Study phase . | Drug class . | Drug name . | Indication . | Intervention arm sample size . | Median follow-up duration, mo∗ . | Rate of CRS† . | Rate of treatment-emergent CVAEs . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmia‡ . | Hypertension . | Coagulopathy§ . | Others . | |||||||||

| Maude et al1,43 | ELIANA | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Tisagenlecleucel | R/R preB-ALL | 79 | 13.1 | 61 (77%) | 2 (4%) | 145 (19%) | 5 (6%) | Cardiac failure, 10 (9%) |

| Schuster et al32,43 | JULIET | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Tisagenlecleucel | R/R DLBCL | 115 | 28.6 | 85 (74%) | 12 (10%) | 5 (4%) | 5 (4%) | Cardiac failure, 1 (1%) |

| Fowler et al35,43 | ELARA | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Tisagenlecleucel | R/R FL | 97 | 16.6 | 51 (53%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (5%) | 2 (2%) | NA |

| Neelapu et al31,44 | ZUMA-1 | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Axicabtagene ciloleucel | R/R LBCL | 108 | 8.7 | 101 (94%) | 25 (23%) | 16 (15%) | 2 (2%) | Cardiac failure, 6 (6%) Cardiac arrest, 4 (4%) |

| Jacobson et al36,44 | ZUMA-5 | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Axicabtagene ciloleucel | R/R iNHL | 146 | 17.5 | 123 (84%) | 31 (21%) | 19 (13%) | 9 (6%) | Cardiac failure, 3 (2%) |

| Locke et al44,45 | ZUMA-7 | Phase 3 | CAR-T | Axicabtagene ciloleucel | R/R LBCL | 168 | 24.9 | 155 (92%) | 24 (14%) | 15 (9%) | 15 (9%) | Cardiac failure, 2 (1%) |

| Wang et al33,46 | ZUMA-2 | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Brexucabtagene autoleucel | R/R MCL | 82 | 12.3 | 75 (91%) | 8 (10%)¶ | 15 (18%) | 8 (10%) | NA |

| Shah et al30,46 | ZUMA-3 | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Brexucabtagene autoleucel | R/R preB-ALL | 78 | 16.4 | 72 (92%) | 12 (15%) | 10 (13%) | 13 (17%) | Cardiac failure, 3 (4%) |

| Kamdar et al3,47 | TRANSFORM | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Lisocabtagene maraleucel | R/R LBCL | 89 | 6.2 | 44 (49%) | 13 (15%)# | 6 (7%) | NA | NA |

| Sehgal et al38,47 | PILOT | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Lisocabtagene maraleucel | R/R LBCL | 61 | 12.3 | 24 (39%) | 6 (10%)# | 6 (10%) | NA | NA |

| Abramson et al34,47 | TRANSCEND | Phase 1 | CAR-T | Lisocabtagene maraleucel | R/R LBCL | 268 | 18.8 | 123 (46%) | 16 (6%) | 38 (14%) | NA | Cardiomyopathy 4 (1.5%) |

| Siddiqi et al48 | TRANSCEND CLL | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Lisocabtagene maraleucel | R/RCLL | 117 | 21.1 | 99 (85%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Munshi et al4,49 | KarMMa | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Idecabtagene vicleucel | R/R MM | 127 | 13.3 | 108 (85%) | 6 (4.7%) | 14 (11%) | 11 (9%) | Cardiomyopathy 2 (1.6%) |

| Rodriguez-Otero et al49,50 | KarMMa-3 | Phase 3 | CAR-T | Idecabtagene vicleucel | R/R MM | 222 | 18.8 | 202 (91%) | 16 (7%) | 31 (14%) | 31 (14%) | NA |

| Berdeja et al39,51 | CARTITUDE-1 | Phase 1/2 | CAR-T | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel | R/R MM | 97 | 12.4 | 92 (95%) | 8 (8%) | 18 (19%) | 21 (22%) | NA |

| Cohen et al40 | CARTITUDE-2 | Phase 2 | CAR-T | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel | R/R MM | 20 | 11.3 | 12 (60%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| San-Miguel et al5,51 | CARTITUDE-4 | Phase 3 | CAR-T | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel | R/R MM | 188 | 15.9 | 147 (78%) | 6 (3%) | 13 (7%) | 9 (5%) | NA |

| Kantarjian et al6,52 | TOWER | Phase 3 | BTE | Blinatumomab | R/R preB-ALL | 267 | 11.7 | 38 (14.2%) | NA | 17 (6.4%) | NA | AMI, 1 (0.4%) Cardiac arrest, 1 (0.4%) Cardiac failure, 1 (0.4%) Pericardial effusion, 1 (0.4%) |

| Locatelli et al52,53 | RIALTO | Phase 3 | BTE | Blinatumomab | R/R preB-ALL | 110 | 17.4 | 18 (16.4%)∗∗ | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Martinelli et al54 | ALCANTARA | Phase 2 | BTE | Blinatumomab | R/R preB-ALL | 45 | 16.1 | 4 (9%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gökbuget et al55 | BLAST | Phase 2 | BTE | Blinatumomab | MRD positive preB-ALL | 116 | 30 | 4 (3%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Moreau et al7,56 | MajesTEC-1 | Phase 2 | BTE | Teclistamab | R/R MM | 165 | 14.1 | 119 (72%) | 26 (16%) | 20 (12%) | NA | NA |

| Dickinson et al8,57 | NP30179 | Phase 2 | BTE | Glofitamab | R/R DLBCL | 154 | 12.6 | 102 (66%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Budde et al9,58 | GO29781 | Phase 1 | BTE | Mosunetuzumab | R/R FL | 90 | 12.6 | 40 (44%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Thieblemont et al10,59 | EPCORE NHL-1 | Phase 1/2 | BTE | Epcoritamab | R/R LBCL | 157 | 10.7 | 80 (51%) | 16 (10%) | NA | NA | AMI, 1 (0.6%) |

| Chesney et al60,61 | C-144–01 | Phase 2 | TIL | Lifileucel | Unresectable/metastatic melanoma | 156 | 27.6 | 5 (3.2%) | 74 (47.4%)# | 21 (13.5%) | NA | Hypotension, 52 (33.3%) |

Reported AEs are treatment emergent, unless otherwise specified. Absolute numbers are derived from percentages and may not represent actual counts.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; iNHL, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma; INR, international normalized ratio; MRD, minimal residual disease; NA, not available; PT, prothrombin time; R/R CLL, relapse/refractory chronic lymphocytic lymphoma; R/R DLBCL, relapse/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; R/R FL, relapse/refractory follicular lymphoma; R/R LBCL, relapse/refractory large B-cell lymphoma; R/R MCL, relapse/refractory mantle cell lymphoma; R/R MM, relapse/refractory multiple myeloma; R/R preB-ALL, relapse/refractory precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

When applicable, median follow-up for overall survival is reported.

Any-grade CRS.

When applicable, any of the following are reported as mention: atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, atrial tachycardia, bradycardia, cardiac arrest, electrocardiogram QT prolonged, electrocardiogram T wave inversion, pulseless electrical activity, sinus bradycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, and ventricular tachycardia. Note, due to the lack of consistency of reporting among trials, the rate reported may coincide with any combination of the aforementioned arrhythmias.

Coagulopathy refers to reporting of any of the following events: disseminated intravascular coagulation, elevated PT/aPTT, elevated INR, and elevated D-dimer.

When applicable, the reported AEs are from the FDA drug insert because it provides more comprehensive data on the reported CVAEs.

Reported rate for both bradyarrhythmia and nonventricular arrhythmia.

Reported as tachycardia includes atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, supraventricular tachycardia, sinus tachycardia, and tachycardia.

Reported as treatment-related AEs.

On the contrary, a lower percentage of BTE patients experienced CRS, with reported rates of up to 16% in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL),6 ∼70% in multiple myeloma7 and ranging from 44% to ∼70% in B-cell lymphoma8-10; additionally, when CRS occurs with BTE therapy, it is less severe.62

CVAEs have been reported across all grades of CRS, with higher grades of CRS being associated with tumor burden as well as other risk factors such as early-onset CRS, infusion dose, as well as the addition of fludarabine to the lymphodepletion regimen.63,64 Occasionally, CVAEs (eg, heart failure and arrhythmias) may occur in the absence of CRS.14,23 Although the grading of CRS may differ among trials, the 2 most widely used criteria are those provided by the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy65 and the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.66 Although they may agree on the major criteria for each CRS grade, the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy system provides more detailed specifications regarding the management of hypotension and hypoxia.

The mechanism underlying CRS involves the release of proinflammatory cytokines including interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and nitric oxide.67,68 Although cytokine release was initially thought to arise from activated T cells, a murine model of CAR-T showed that the severity of CRS was mediated by cytokines produced by macrophage and monocyte activation, perpetuating a vicious cycle of inflammation.69,70 The downstream signals of these cytokines enable the trafficking of immune cells out of circulation, resulting in vascular leakage and hypotension.71 Meanwhile, tumor necrosis factor α signaling induces endothelium to express tissue factors, contributing to the prothrombotic events in severe CRS.68 Additionally, high levels of von Willebrand factor and angiopoietin-2 have been linked to severe states of CRS in patients receiving CAR-T therapy.63,72 These molecules may lead to endothelial activation and the activation of coagulation cascades, contributing to the development of coagulopathy.73

Preclinical studies have identified IL-6 and IL-1 as the major mediators of CRS,69,70 a finding further corroborated by clinical studies showing an association between CRS severity and levels of IL-6,74 leading to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab for the treatment of severe CRS in 2017.75 Early results from clinical studies with IL-1 inhibitor anakinra have demonstrated the promising activity of IL-1 inhibitors in treating CRS.76 Currently, anakinra is being investigated for its potential in both preventing and managing CRS associated with T-cell–based therapies.77-79

From a cardiovascular perspective, the downstream effects of CRS may explain many of the clinically observed CVAEs, including hypotension, arrhythmias, left ventricular dysfunction, decompensated heart failure, and shock.80 Across CAR-T trials, the median onset of CRS has preceded cardiovascular events, with cardiac toxicity commonly occurring within the CRS interval.81 This association is further supported by real-world studies,14,82-84 with 1 pharmacovigilance study reporting an almost twofold risk of CVAEs in patients with CRS.84 Additionally, more severe cardiac events such as fluid-refractory hypotension, myocardial ischemia, as evidenced by troponin elevation, stress cardiomyopathy, pericarditis, and pericardial effusion are associated with higher-grade CRS.14,22,82,83,85-88

It has been hypothesized that the mechanism of CRS-mediated cardiotoxicity mirrors that of systemic inflammatory response syndrome.28,64 Specifically, the aforementioned proinflammatory cytokine release leads to vascular and cellular disruption due to oxidative stress and altered calcium signaling, which ultimately leads to impaired endothelial integrity,64 all of which contribute to acute hemodynamic changes which may trigger the CVAEs mentioned above.89 Nonetheless, more research is still needed to fully explain the precise mechanisms connecting CRS to cardiotoxicity.

Non-CRS pathways of cardiotoxicity development

Other proposed hypotheses for CAR-T–mediated cardiotoxicity include direct myocardial damage from recognition of cardiac antigens, either due to antigen mimicry or alloreactivity. Fatal myocarditis in 2 patients has been reported, 1 with melanoma and the other with multiple myeloma, receiving CAR-T-cells targeting the MAGE-A3 tumor antigen, due to cross-reactivity with titin, a sarcomere protein in cardiomyocytes.64 Analogous to graft-versus-host disease, alloreactivity has also been linked to cardiotoxicity, in which administered T cells respond to unrecognized major histocompatability complex variants in host cardiac tissue, leading to cardiac damage.26

Cardiovascular toxicities observed in clinical practice

Evidence from randomized controlled trials reporting the cardiovascular toxicity of cellular therapies is limited. These trials frequently excluded patients with preexisting cardiovascular conditions, a cohort that is at a higher risk of cardiotoxicity.10,11 Additionally, most trials were not powered to detect less common AEs, such as CVAEs, because their primary focus was on detecting differences in cancer-related outcomes. However, observational studies have highlighted the prevalence of CVAEs in patients receiving CAR-T and BTE therapies.14,15,22,23,82,83,85-88,90-94

The most frequently reported cardiovascular side effects associated with CRS are hypotension and arrhythmia occurring with both CAR-T and BTE therapies.27,81 Trials on both report hypertension in up to 19% of patients (Table 1); however, many of these trials are single-armed studies, thus limiting the ability to determine whether it was directly related to therapy.

CAR-T therapy

In the past decade, 6 CAR-T therapies have received FDA approval for various hematologic malignancies in the relapsed or refractory setting, including precursor B-ALL, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and multiple myeloma.1,3-5,30,33-40,80,95 In the major clinical trials, refractory shock, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and heart failure were the reported cardiovascular side effects (Table 1).

Similarly, in practice, arrhythmias are the most commonly reported cardiovascular toxicities after CAR-T therapy, although the reported incidence in studies is inconsistent (Table 2). A comprehensive pharmacovigilance study of 2657 patients receiving CAR-T therapy found that CAR-T–related AEs were almost 3 times as likely to involve tachyarrhythmias.22 The most frequently reported arrhythmias included sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, ventricular arrhythmia, and corrected QT interval prolongation, possibly corresponding to the inflammatory state and hemodynamic changes of CRS.22

CVAEs reported in cohort and pharmacovigilance studies evaluating cellular therapies

| Study . | Study type . | Drug class . | Sample size . | Median follow-up duration, mo . | Rate of CRS∗ . | Reported rates of CVAEs . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmia . | Cardiac decompensation . | Left ventricular dysfunction . | Cardiac ischemia† . | Cardiomyopathy . | Cardiac death . | Hypertension . | Hypotension/shock . | Coagulopathy . | Others . | ||||||

| Burstein et al91 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 93 | 6‡ | 24 (25.8%) | NA | NA | 10 (10%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 24 (25%) | NA | NA |

| Alvi et al82 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 137 | 10 | 81 (59%) | 5 (3.6%) | 6 (4.4%) | NA | NA | NA | 6 (4.4%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lefebvre et al83 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 145 | 15 | 104 (72%) | 11 (7.5%) | 22 (15%) | NA | 2 (1.4%) | NA | 2 (1.4%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Shalabi et al85 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 52 | NA | 37 (71%) | NA | NA | 6 (12%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9 (17%) | NA | NA |

| Ganatra et al23 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 187 | 5.5 | 155 (83%) | 13 (7.0%) | NA | NA | NA | 12 (10.3%)§ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brammer et al87 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 90 | 16.5 | 80 (88.9%) | 11 (12.2%) | 1 (1.1%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 (3.3%); other myocarditis, 2 (2.2%) |

| Qi et al88 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 126 | 1.6‡ | 103 (81.7%) | 7 (6%) | 15 (12%) | 1 (1%) | 9 (7%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | New valve disease, 1 (1%) |

| Goldman et al22 | Pharmacovigilance|| | CAR-T | 2657 | NA | 1457 (54.84%) | 74 (2.79%) | NA | NA | 12 (0.45%) | 69 (2.6%) | NA | 18 (0.68%) | 286 (10.76%) | NA | Cardiogenic shock, 49 (1.84%); pericardial disease, 11 (0.41%); myocarditis, 2 (0.08%) |

| Korell et al94 | Prospective | CAR-T | 137 | 8.8‡ | 75 (54.7%) | 5 (4%) | 17 (12%) | 4 (3%) | NA | NA | NA | 2 (1%) | 25 (18%) | NA | NA |

| Wudhikarn et al86 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 60 | 9 | NA | 8 (13.3%) | NA | 3 (5%) | NA | NA | NA | 5 (8.3%) | 28 (46.6%) | 8 (13.3%) | Pericardial effusion, 1 (1.67%) |

| Lefebvre et al93 | Prospective | CAR-T | 44 | 16 | 23 (52%) | 1 (1.67%) | 1 (1.67%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Jung et al92 | Retrospective | BTE | 50 | NA | 10 (20%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 (14%)¶ |

| Sayed et al15 | Pharmacovigilance|| | BTE | 3668 | NA | NA | 45 (1.22%) | 52 (1.4%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 193 (5.26%) | NA# | Myocarditis, 8 (0.22%); pericarditis, 4 (0.1%) |

| Fradley et al90 | Retrospective | TIL | 43 | NA | NA | 6 (14%) | NA | NA | 1 (2.3%) | NA | NA | NA | 14 (32.6%) | NA | NA |

| Study . | Study type . | Drug class . | Sample size . | Median follow-up duration, mo . | Rate of CRS∗ . | Reported rates of CVAEs . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmia . | Cardiac decompensation . | Left ventricular dysfunction . | Cardiac ischemia† . | Cardiomyopathy . | Cardiac death . | Hypertension . | Hypotension/shock . | Coagulopathy . | Others . | ||||||

| Burstein et al91 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 93 | 6‡ | 24 (25.8%) | NA | NA | 10 (10%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 24 (25%) | NA | NA |

| Alvi et al82 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 137 | 10 | 81 (59%) | 5 (3.6%) | 6 (4.4%) | NA | NA | NA | 6 (4.4%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lefebvre et al83 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 145 | 15 | 104 (72%) | 11 (7.5%) | 22 (15%) | NA | 2 (1.4%) | NA | 2 (1.4%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Shalabi et al85 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 52 | NA | 37 (71%) | NA | NA | 6 (12%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9 (17%) | NA | NA |

| Ganatra et al23 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 187 | 5.5 | 155 (83%) | 13 (7.0%) | NA | NA | NA | 12 (10.3%)§ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brammer et al87 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 90 | 16.5 | 80 (88.9%) | 11 (12.2%) | 1 (1.1%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 (3.3%); other myocarditis, 2 (2.2%) |

| Qi et al88 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 126 | 1.6‡ | 103 (81.7%) | 7 (6%) | 15 (12%) | 1 (1%) | 9 (7%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | New valve disease, 1 (1%) |

| Goldman et al22 | Pharmacovigilance|| | CAR-T | 2657 | NA | 1457 (54.84%) | 74 (2.79%) | NA | NA | 12 (0.45%) | 69 (2.6%) | NA | 18 (0.68%) | 286 (10.76%) | NA | Cardiogenic shock, 49 (1.84%); pericardial disease, 11 (0.41%); myocarditis, 2 (0.08%) |

| Korell et al94 | Prospective | CAR-T | 137 | 8.8‡ | 75 (54.7%) | 5 (4%) | 17 (12%) | 4 (3%) | NA | NA | NA | 2 (1%) | 25 (18%) | NA | NA |

| Wudhikarn et al86 | Retrospective | CAR-T | 60 | 9 | NA | 8 (13.3%) | NA | 3 (5%) | NA | NA | NA | 5 (8.3%) | 28 (46.6%) | 8 (13.3%) | Pericardial effusion, 1 (1.67%) |

| Lefebvre et al93 | Prospective | CAR-T | 44 | 16 | 23 (52%) | 1 (1.67%) | 1 (1.67%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Jung et al92 | Retrospective | BTE | 50 | NA | 10 (20%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 (14%)¶ |

| Sayed et al15 | Pharmacovigilance|| | BTE | 3668 | NA | NA | 45 (1.22%) | 52 (1.4%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 193 (5.26%) | NA# | Myocarditis, 8 (0.22%); pericarditis, 4 (0.1%) |

| Fradley et al90 | Retrospective | TIL | 43 | NA | NA | 6 (14%) | NA | NA | 1 (2.3%) | NA | NA | NA | 14 (32.6%) | NA | NA |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not available.

Includes any-grade CRS.

Includes events reported as ACS or MI.

Reported as overall follow-up duration.

Percentage out of 116 patients with available imaging.

Reported rates from pharmacovigilance studies are the proportions representing the reporting of a particular AE of all drug-related AE reports.

Includes “cardiovascular disease/events” not otherwise specified.

Increased reporting odds of DIC events was found to be statistically significant; however, the proportion of reported events was not stated.

Other cardiovascular side effects reported with CAR-T therapy include cardiomyopathy, heart failure, pericardial disease, and coagulopathy. In a retrospective study, new or worsening cardiomyopathy was detected in 10.3% of 116 patients within months of treatment.23 In the aforementioned pharmacovigilance study, patients receiving CAR-T were 3.5 times as likely to report cardiomyopathy and twice as likely to report pericardial disease compared with non–CAR-T therapies.22 Moreover, coagulopathy, defined as an elevation in laboratory coagulation parameters and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), was also reported in the major clinical trials,1,31,35-37 particularly with brexucabtagene autoleucel30,33 (Table 1); however, it is unclear whether it was directly treatment-related because these trials were single-armed and lacked a control group. Moreover, this finding is further supported by retrospective studies. In a study of patients with B-cell lymphomas, a coagulopathy rate of 13.3% was reported, with only 1 patient presenting with DIC.86 Another study found an association between the occurrence of coagulation disorders and CRS, reporting a coagulopathy rate of 51%, with 7 patients developing DIC.96

Hypotension, shock, and congestive heart failure have also been noted in major clinical trials and real-world studies (Tables 1 and 2). Hypotension and shock were generally attributed to severe CRS, whereas congestive heart failure was reported in only 1 patient at most in these trials (Table 1). Postmarketing studies have provided further insight into the incidence of heart failure with CAR-T therapy, reporting incidence rates that range from 1% to 15% (Table 2); however, due to the retrospective nature of these studies and heterogeneous patient populations, the exact incidence of these CVAEs remains uncertain. Similarly, despite considerations for potentially lower toxicity (eg, outpatient) in non-CD28–focused products, CRS and cardiac events have still been reported,5,41,42 and the long-term risk of more insidious or later CVAE events, such as arrhythmias and heart failure, remains undefined.

Additionally, studies reporting on major adverse cardiac event (MACE) rates after CAR-T therapy show inconsistent results. MACE is a composite outcome generally defined as the occurrence of ≥1 of the following: cardiovascular death, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, acute coronary syndrome, ischemic stroke, or de novo (incident) symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia. Although the exact components included in MACE may vary between studies, it consistently includes at least 1 of these cardiovascular events or their variations.

A recent prospective study reported no MACE events in 137 patients treated with CAR-T cells.94 Conversely, 1 retrospective study found a 21% cumulative incidence of MACE within 1 year after infusion,83 whereas a more recent prospective study of 44 relatively healthier patients reported a MACE rate of <5%.93 Despite differing populations and study designs, the discrepancies reported emphasize the need for better characterization of the cardiotoxic profile of CAR-T therapy and the need to unify and standardize reporting outcomes.

A notable finding from the aforementioned pharmacovigilance study was the differing cardiotoxic profiles observed between axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel, with tisagenlecleucel having a slightly more favorable cardiac safety profile and lower reporting rates of CRS, arrhythmias, and other severe CVAEs22; this distinction was also reported in another pharmacovigilance study by Guha et al.84 However, given the inherent limitations of retrospective studies, this observation serves merely as a signal that warrants further investigation into the potential reasons for this difference. In particular, this discrepancy raises questions regarding whether differences in CAR-T costimulatory domains, patient characteristics, or dosing strategies could contribute to the onset of CVAEs; all of which need to be addressed in a prospective manner.

BTE therapy

To date, 7 BTE therapies have been FDA approved for the treatment of B-ALL, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and multiple myeloma in the relapsed/refractory setting.6-10,54,97 However, the clinical trials for BTE therapies are mainly small-scale phase 2 studies, often enrolling <100 patients; consequently, they were underpowered to detect cardiotoxicity.

Arrhythmias were the most frequently reported CVAEs in major BTE trials.27,81 Trials for the relatively newer BTE therapies such as talquetamab,98 elranatamab,99 mosunetuzumab,9 epcoritamab,10 and glofitamab8 did not report specific CVAEs.

Despite the limitations of clinical trials, real-world data provide some insight into the cardiotoxicity associated with BTE therapy, although it remains somewhat inconsistent. In a large-scale pharmacovigilance study, CVAEs were reported in 1 of every 5 AEs related to BTE therapies.15 Of note, teclistamab, but not other BTE products, was associated with an excess of fatal cardiovascular events and myocarditis. Additionally, DIC was almost 3 times as likely to be reported with BTEs, a finding that was likely driven by blinatumomab. Interestingly, this study found no association between CVAEs and CRS; considering the lower incidence and severity of CRS observed with BTE therapy, alternative mechanisms may be contributing to cardiotoxicity. However, 1 limitation of this study was that it reported data only on blinatumomab and teclistamab, because few data were available on the more recently approved BTE therapies at the time.

Risk factors for cellular therapy–associated cardiotoxicities

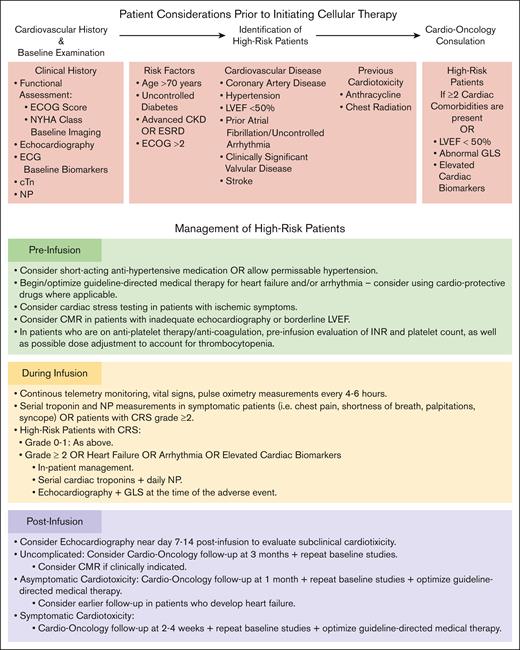

Several key factors may increase the risk of cardiotoxicity, including advanced age, presence of baseline comorbidities such as uncontrolled diabetes, renal dysfunction, coronary artery disease, and heart failure, and prior receipt of cardiotoxic chemotherapy regimens such as anthracyclines or mediastinal radiotherapy.23,24 Thus, a thorough pretreatment assessment of cardiovascular health and risk stratification is essential for identifying patients requiring more intensive monitoring (Figure 2).

Identification and management of patients at high-risk of cardiotoxicity. Clinical considerations for the screening and management of patients at an increased risk of cardiotoxicity undergoing T-cell–directed therapy. CKD, chronic kidney disease; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; ECG, electrocardiography; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ESRD, end stage renal disease; GLS, global longitudinal strain; INR, international normalized ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Identification and management of patients at high-risk of cardiotoxicity. Clinical considerations for the screening and management of patients at an increased risk of cardiotoxicity undergoing T-cell–directed therapy. CKD, chronic kidney disease; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; ECG, electrocardiography; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ESRD, end stage renal disease; GLS, global longitudinal strain; INR, international normalized ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Prognostic implications of cellular therapy–associated cardiotoxicity

The long-term risks of sustained, cardiotoxicity-related morbidity and mortality associated with T-cell treatments remain unclear due to the lack of extended follow-up data. Current long-term studies have limited follow-up durations, ranging from 9 months14 to 16.5 months.87 In studies with relatively longer follow-up (5-16.5 months),14,23,83,87 the majority of CVAEs were reported to occur within 3 months of CAR-T initiation, with a median time to cardiac event of ∼1 to 2 weeks; however, the long-term impact of these events remains unclear. In a retrospective study of 202 CAR-T patients, 16% experienced severe cardiovascular events including myocardial infarction, cardiovascular shock, or heart failure.14 Patients with these severe CVAEs had a risk of mortality that was nearly 3 times that of those without severe CVAEs. Similarly, a pharmacovigilance study on BTE therapy shows that when they do occur, CVAEs associated with BTE therapy are more fatal than other AEs reported with BTE therapy.15 Reassuringly, there is some evidence indicating that cardiotoxicity is often reversible without lasting impact23,91,100; however, this evidence is inconclusive. This lack of long-term studies represents a gap in the literature that warrants investigation as we continue to develop and expand the use of cellular therapies.

Diagnostic algorithm for cellular therapy–associated cardiotoxicities

Pretreatment evaluation

Comprehensive baseline cardiac screening is recommended for all patients before initiating T-cell therapy (Figure 2). This includes cardiac biomarkers such as cardiac troponin (cTn) and natriuretic peptides (NPs; including brain natriuretic peptide and NT-pro-brain natriuretic peptide) to serve as a baseline for the early detection of infarction or heart failure. A 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) is also recommended to allow for the evaluation of new-onset ischemia and arrhythmia. Additionally, transthoracic echocardiography with global longitudinal strain to assess baseline ventricular function and allow for risk stratification may be performed. In potentially high-risk patients, such as those with borderline reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (eg, 45%-50%), intracardiac malignant disease involvement, or even with inadequate transthoracic echocardiography image quality (Figure 2), more advanced imaging such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may be warranted to define and/or exclude underlying cardiac dysfunction; whereas cardiac stress testing may best appropriate in those with potential coronary ischemia.101,102 Together, these may provide additional key insights into the ability to tolerate hemodynamic changes during therapy.81,100

Posttreatment evaluation

Ongoing postinfusion surveillance may incorporate serial ECGs, repeat echocardiography for any new symptoms, and frequent assessment of cTn and NPs for myocardial injury/stress (Figure 2). Subject to their availability, tracking inflammatory markers, such as IL-6 and IL-1, may also provide early warning signals for cardiotoxicity.81,103 If echocardiography is inadequate or inconclusive, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may be considered. Although evidence on predictive inflammatory/biomarker cutoffs remains limited, their elevations have been associated with increased cardiovascular events. For example, studies have identified associations between cardiovascular events and elevated IL-6, as well as ferritin and troponin.14,23,63,82,83,91 In a recent prospective study on patients receiving CAR-T, an association between high-sensitivity troponin and all-cause mortality was reported, suggesting that patients with elevated high-sensitivity troponin may benefit from more intensive postinfusion monitoring and early intervention.94 However, further research is still needed to establish definitive biomarker thresholds for the prediction of cardiotoxicity.

Prevention and management of cellular therapy–associated cardiotoxicities

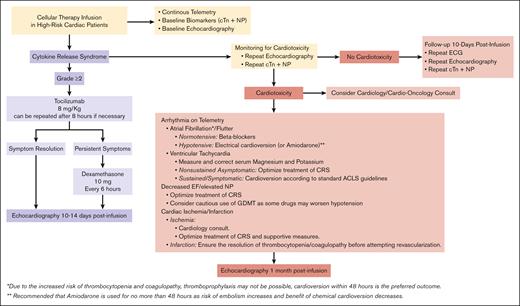

Management of CRS

Due to the close association between CRS and cardiotoxic symptoms, most recommendations aim at the prevention or early management of CRS (Figure 3). Supportive care and antipyretics suffice for low-grade CRS, whereas severe CRS warrants tocilizumab, corticosteroids, and hemodynamic support.80 Recently, a more potent IL-6 inhibitor, siltuximab, has shown promise for CRS in trials but requires further study.104

Management of patients with CRS and/or cardiotoxicity. Proposed algorithm for the management of high-risk cardiac patients who develop CRS and/or cardiotoxicity during treatment with T-cell–directed therapy. ACLS, advanced cardiac life support; ECG, electrocardiography; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy.

Management of patients with CRS and/or cardiotoxicity. Proposed algorithm for the management of high-risk cardiac patients who develop CRS and/or cardiotoxicity during treatment with T-cell–directed therapy. ACLS, advanced cardiac life support; ECG, electrocardiography; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy.

Early intervention with preventive drugs in patients developing early signs of CRS has been suggested as a potential strategy to mitigate severe CRS. In ZUMA-1, early intervention with tocilizumab and corticosteroids led to an absolute risk reduction of 11% in the rate of severe CRS (2% in the group with early intervention vs 13% in the group without early intervention).105 Consistently, early preventive intervention has reduced CRS rates across various studies.106,107 However, despite these promising results, heterogeneity in management across centers and the lack of robust evidence have limited the initiation of standard preventive recommendations on the use or timing of these drugs.

Moreover, the prophylactic use of tocilizumab on day 2 after infusion for the prevention of severe (grade ≥3) CRS was evaluated in subsequent analyses of the ZUMA-1 trial.2,31 Preliminary results showed an incidence of severe CRS of 13% in the cohort receiving no prophylaxis compared with 3% in the cohort receiving prophylactic tocilizumab. The same trial also evaluated the use of prophylactic corticosteroids (dexamethasone), demonstrating an incidence of severe CRS of 0% in the dexamethasone group compared with 13% in the group receiving no prophylaxis.108 However, it is important to note that the cohort receiving corticosteroids had a lower tumor burden, which could have contributed to the overall lower incidence of CRS observed. Consequently, given the lack of robust data available, prophylactic management of CRS is not currently the standard of care and warrants further investigation in randomized controlled studies.

Management of cardiotoxicity

Beyond the early or prophylactic use of targeted therapies such as tocilizumab, prevention and management rely on retrospective data and traditional cardio-oncologic strategies. High-risk patients warrant monitoring for cardiotoxicity with telemetry, ECG, echocardiograms, cTn, and NP testing for the early detection of arrhythmias and circulatory collapse, as supported by the European Society of Cardiology cardio-oncology opinion guidelines.103 Cardiovascular complications should be managed by standard protocols. Additionally, permissive hypertension by withholding antihypertensive medication in high-risk patients has been proposed to address circulatory fluctuations,81 but limited evidence currently exists to support this recommendation.

Future directions

There is wider applicability of cellular therapies in hematologic and solid tumor cancers, and this will only continue to grow in the future. Although initial studies and pharmacovigilance data have revealed concerning safety signals, our current understanding of the cardiovascular risks and mechanisms of T-cell–based therapy is limited. Additionally, research on the cardiovascular effects of emerging T-cell therapies such as BTEs is scarce, with many gaps of knowledge in the available evidence (Table 3). With ongoing trials of BTEs in non-cancer–related indications, awareness and surveillance for potential cardiotoxicity in these wider patient populations is critical.

Key unanswered questions and future directions

| Key unanswered questions . | Future directions . |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis and surveillance | |

|

|

| Management and prevention | |

CRS

|

|

| Risk factors | |

|

|

| Long-term prognostic implications | |

|

|

| Key unanswered questions . | Future directions . |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis and surveillance | |

|

|

| Management and prevention | |

CRS

|

|

| Risk factors | |

|

|

| Long-term prognostic implications | |

|

|

RCT, randomized controlled trial.

CAR-T therapy has the most well-documented evidence so far; yet, studies defining the underlying pathways, incidence rates, and risk factors for cardiovascular events are still insufficient. Current research on newer autologous CAR-T constructs, both in hematologic malignancies and solid tumors, as well as allogeneic and armored CAR-T approaches is promising, although it leaves us with the worry of potential cardiotoxicity. Although the promise of improved tumor specificity using armored CAR-Ts provides hope for possibly fewer CVAEs, the use of donor-derived cells in allogeneic CAR-T regimens allowing for more widespread treatment is of concern. This broader reach, compounded with the unpredictable off-target risks that may occur, means the widespread use of allogeneic CAR-T therapy could magnify the CVAE signals that we are seeing now. Hence, there is a critical need to better characterize the cardiotoxicity profile of these emerging cellular therapies before large-scale adoption.

The expansion of adoptive cellular therapies to the treatment of solid tumor malignancies, as seen recently with the approval of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), brings forth the potential for cardiovascular toxicity. However, these risks are unclear, because several trials have failed to incorporate specific measures for detecting CVAEs in their design. Furthermore, recently reported studies with TILs for the treatment of melanoma60,109 have incidentally documented a severe risk of hypotension, possibly leading to cardiac ischemia. A retrospective study90 has also identified the risk of CVAEs with TIL therapy.

Efforts to predict, identify, and prevent cardiovascular toxicity should remain a priority for studies on T-cell therapies. In line with this focus, future research should also explore the development of targeted deterrence techniques, such as molecular safety switches and genetic modifications,110 aimed at preventing the onset of these AEs. However, it is important to note that these advancements are contingent upon establishing comprehensive cardiotoxic profiles for individual cellular therapies.

Multidisciplinary collaboration between cardiologists and oncologists and the strengthening of pharmacovigilance reporting are essential to fully evaluate cardiovascular outcomes. Additionally, standardized safety end points in trials along with registry data can help outline long-term cardiotoxicity profiles; thus, collaboration efforts among researchers, regulatory agencies, and physicians are paramount for maximizing the potential of these novel cellular therapies while ensuring patients safety.

Conclusion

Cellular therapies have revolutionized the treatment of hematologic malignancies and many solid tumors. Yet, cardiotoxicity remains a potential limitation to the effective application of these therapies. Understanding the effects of these rapidly proliferating therapies will facilitate the targeted prevention and control of these AEs. Multidisciplinary strategies inclusive of cardio-oncologic assessments and shared decision-making with patients, cardiologists, and oncologists are needed to facilitate increased applications of these impactful therapies. Despite gaps in current evidence, existing data may provide a basis for future investigations focused on defining the true incidence, effects, and burden of cardiotoxicity among cellular therapy–treated patients. Together, these provide compelling impetus for additional studies focused on defining the mechanisms and optimal preventive strategies for cardiac toxicities among cancers requiring these therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P50-CA140158. D.A. is supported by NIH grants K23-HL155890, R01HL168045, and R01HL170038, and an American Heart Association-Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Harold Amos) grant.

The manuscript’s content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: N.E. and D.A. contributed to conceptualization and study design; M.M. and A.S. contributed to writing/editing the first draft of the manuscript; and N.E. and D.A. provided critical review and comments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Narendranath Epperla, Division of Hematology and Hematologic Malignancies, Department of Medicine, Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, UT 84103; email: naren.epperla@hci.utah.edu.

References

Author notes

D.A. and N.E. contributed equally to this study.

Data reported was obtained from published trials and US Food and Drug Administration drug inserts.