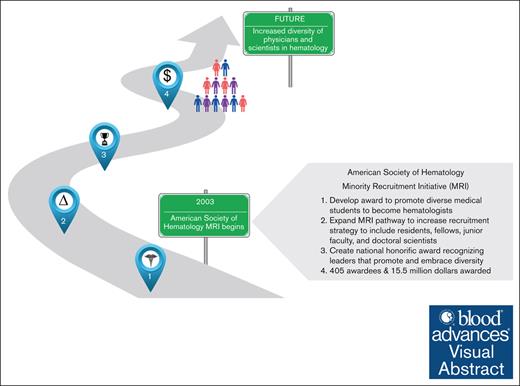

Visual Abstract

In 2003, the Institute of Medicine noted the need to improve workforce diversity. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) responded by developing the Minority Recruitment Initiative (MRI) to recruit diverse physicians/scientists into hematology. We evaluated the outcomes of the program. From 2004 to 2022, there were 405 awardees. Compared with national estimates, MRI awardees were less likely to discontinue their degree programs. MRI graduate student awardees had 0% attrition (97.5% confidence interval [CI], 10.6), whereas the national minority graduate student attrition was 36%. Medical student awardees had 2.2% (95% CI, 0.61-5.6) attrition, compared with the minority medical school attrition of 5.6%. Awardees were more likely than expected to pursue hematology-oncology (5.7% minority national estimate) because 14.4% (95% CI, 8.1-23.0) of medical student awardees and 88.5% (95% CI, 70.0-97.6) of early career awardees remain in the field. ASH has developed a successful program, but continued efforts are needed to advance equity in hematology.

Introduction

The diversity of the scientific and health care workforce in the United States is not representative of the population that it serves.1 It has been shown that diversity in the physician workforce improves patient health and treatment outcomes.2 Individuals from backgrounds underrepresented in medicine are more likely to serve communities of color, which in turn increases health care access to socially disadvantaged groups, decreases health care disparities, and improves diversity in clinical trials. Patients treated by physicians from the same race or ethnicity report improved satisfaction with treatment and improved patient-provider communication.3 In 2003, the Institute of Medicine recognized the need to diversify the medical workforce, noting that diverse clinicians would have a positive impact on patient-physician communication and engagement with racial and ethnic minority populations, and ultimately improve health care inequities.4

African Americans constitute 13.6% of the US population, yet they represent only 4.1% of hematology-oncology trainees.3 Similarly, Hispanic/Latin/o/a/x individuals represent 18.9% of the US population but constitute only 5.7% of hematology-oncology trainees.3 Furthermore, for historically underrepresented minority groups (Black/African American, Hispanic/Latin/o/a/x, Native American/Alaskan Natives, Pacific Islander, Inuit, or First Nation Peoples), there is considerable attrition at each educational level, representing the challenging path to completing medical education and training to become academic faculty.3

Underrepresented minority students with science, technology, engineering, and math majors are more likely to transfer to nonscience majors before graduation than their White counterparts.5,6 In fact, in 2022, only 9% of doctoral recipients in science/engineering fields identified as Hispanic/Latin/o/a/x, 6% identified as Black, and 0.5% identified as Native American/Alaskan Natives.7 Additionally, Black and Hispanic doctoral students in science majors are less likely to receive financial stipends compared with their White counterparts. As a result, 81% of Black or Hispanic doctoral students borrowed over $40 000 in loans to obtain their graduate education, compared with only 6% of White doctoral students.8

In recent years, there has been a renewed focus on the barriers that continue to limit diversity and equity, with a concomitant recognition of the structural, racist policies and systems that exist as barriers to success.9 Programs promoting diversity and inclusion have existed for decades. However, they have not demonstrated significant success in changing the demographics of medicine and science, with some data suggesting that they can be counterproductive.10 In fact, despite prolonged efforts to create pathway programs aiming at improving the diversity of the physician workforce, the majority of medical school graduates continue to self-identify as White.1,11

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) was a pioneer in responding to the call to action from the Institute of Medicine and developed programs meeting the needs of racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine to increase the diversity of physicians and scientists in hematology. ASH demonstrated early and sustained commitment to promoting diversity and equity at a time when it was rare for societies to engage in this work. Here, we evaluate the success of ASH’s Minority Recruitment Initiative (MRI) program and highlight areas for improvement.

Methods: history and mechanisms

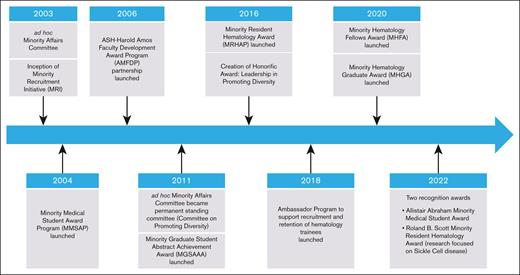

The governance structure of ASH includes an executive committee and 14 standing committees that recommend policies, programs, and actions to the executive committee. Each Committee has its own mandate. The Minority Affairs Committee was created in 2003 as an ad hoc committee with the mandate to improve diversity in the hematology workforce. To address this mandate, the committee launched the MRI. Subsequently, ASH created a summer research award for minority medical students, the Minority Medical Student Award Program. Within 2 years of launching the initiative, ASH expanded the MRI’s outreach to include the retention of early career faculty. This was accomplished by partnering with the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (AMFDP), a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation that was created in 1983 to increase the number of health care professionals from historically disadvantaged backgrounds remaining in academic medicine.12 Through this partnership, ASH began to financially support 1 to 2 early career (ASH-AMFDP) awardees per year (Figure 1).

Eight years after its formation, the ad hoc Minority Affairs Committee transitioned to a permanent standing committee, renamed the Committee on Promoting Diversity. In that same year, ASH recognized the additional need to support doctoral scientists and created the Minority Graduate Student Abstract Achievement Award. As the MRI grew, ASH was responsive to feedback from volunteers, mentors, and awardees and enhanced the initiative as needed. For example, in 2016, ASH created a national honorific award to recognize leaders who promote and embrace diversity. In 2018, the ASH Ambassador Program was created to help improve the geographical diversity of applicants. By 2022, 3 additional awards had been developed, resulting in an unbroken longitudinal pathway of support for clinical and doctoral scientists (Figure 1).

All MRI awards include mentorship and a paid research opportunity. These key components have been shown to improve diversity in science fields. Studies have reported minority students who participate in mentoring programs have lower attrition, higher grade point averages, and increased self-efficacy.5 Furthermore, career development mentors have been shown to help underrepresented students navigate challenges, such as the unwelcoming climates that are often present in higher education.6 Finally, minority students who participate in research opportunities, particularly paid internships, are more likely to be retained in science, technology, engineering, and math careers.5

Awards pathway

Currently, the MRI encompasses 6 awards and applicants apply for an award based on their degree and/or career level (Table 1). The longitudinal pathway for clinical scientists (physicians or physicians in training includes 4 awards): (1) the medical student award, Minority Medical Student Award Program; (2) the resident award, Minority Resident Hematology Award Program; (3) the fellow award, Minority Hematology Fellow Award; and (4) the early career award, ASH-AMFDP. The longitudinal pathway for doctoral scientists includes 3 awards: (1) the graduate student abstract achievement award, Minority Graduate Student Abstract Achievement Award; (2) the graduate student award, Minority Hematology Graduate Award; and (3) the fellow award, Minority Hematology Fellow Award.

The medical student award was the inaugural award developed by the MRI in 2004. This award has been expanded over time and currently includes opportunities for participation throughout medical school. A critical component of this award is a dual mentorship structure that pairs each awardee with both a research mentor and a career development mentor. The career development mentor’s role is to support the medical student by giving advice to navigate challenges or difficult environments, encourage them to apply for additional ASH awards, and provide holistic support through medical school and beyond. A financial stipend is provided to the student, and additional funds are provided to support the research project. After their first experience, medical student awardees are encouraged to apply for an additional experience to support ongoing mentorship and research.

The resident award was developed as a “next step” on the longitudinal pathway after the medical student award. Similar to the medical student award, the resident award also includes the dual mentorship structure. The goal of this award is to provide research support for a hematology-related project that is conducted part-time (320-480 hours) over the course of 1 year. A stipend is provided to the student, and additional funds are provided to support the research project. After their initial award, resident awardees are encouraged to apply for an additional experience to support ongoing mentorship and research.

The fellow award is the only award open to both medical and doctoral trainees. The goal of the fellow award is to provide protected time for clinical fellows or postdoctoral graduate students to generate sufficient expertise or preliminary data to be competitive when applying for future awards. The fellow award provides salary support as well as funds to support a hematology research project for a 2- or 3-year period. Due to the nature of the fellow award, it is not renewable.

The early career award allows a physician committed to a career in academic medicine protected time to conduct research. This award provides 4 years of salary support as well as funds to support a hematology research project. Due to the nature of the early career award, it is not renewable.

The graduate student abstract achievement award is the only award that provides recognition for research already conducted. This award recognizes doctoral students who are authors of abstracts that have been accepted for an oral or poster presentation at the ASH annual meeting. Initially this award was given as a travel stipend to encourage attendance at the ASH annual meeting; however, the graduate student abstract achievement award is currently given as a stipend in recognition of meritorious science. Previous awardees are encouraged to reapply for the award in subsequent years if the eligibility criteria are met.

The graduate student award encourages doctoral students to pursue a career in academic hematology. The graduate student award provides 2 years of funding for salary support, the hematology research project, training-related expenses, and travel to the ASH annual meeting. Due to the nature of the graduate student award, it is not renewable.

ASH MRI pathway by career level

| Degree and career level . | Medical school/graduate school . | Medical school/graduate school . | Residency . | Fellow . | Early career . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years 1-3 . | Years 4-5 . | Years 1-3 . | Years 1-2 . | ||

| MD or DO | MMSAP∗ | MMSAP∗ | MRHAP† | MHFA‡ | ASH-AMFDP§ |

| MD-PhD or DO-PhD | MGSAAA||, MMSAP∗ | MGSAAA||, MHGA¶ | MRHAP† | MHFA‡ | ASH-AMFDP§ |

| Graduate School | Graduate School | Postdoctoral | |||

| Years 1-3 | Years 4-5 | Years 1-2 | |||

| PhD | MGSAAA†, MHGA‡ | MGSAAA† | N/A | MHFA | N/A |

| Degree and career level . | Medical school/graduate school . | Medical school/graduate school . | Residency . | Fellow . | Early career . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years 1-3 . | Years 4-5 . | Years 1-3 . | Years 1-2 . | ||

| MD or DO | MMSAP∗ | MMSAP∗ | MRHAP† | MHFA‡ | ASH-AMFDP§ |

| MD-PhD or DO-PhD | MGSAAA||, MMSAP∗ | MGSAAA||, MHGA¶ | MRHAP† | MHFA‡ | ASH-AMFDP§ |

| Graduate School | Graduate School | Postdoctoral | |||

| Years 1-3 | Years 4-5 | Years 1-2 | |||

| PhD | MGSAAA†, MHGA‡ | MGSAAA† | N/A | MHFA | N/A |

DO, doctor of osteopathic medicine; MD, doctor of medicine; MGSAAA, Minority Graduate Student Abstract Achievement Award; MHFA, Minority Hematology Fellow Award; MHGA, Minority Hematology Graduate Award; MMSAP, Minority Medical Students Award Program; MRHAP, Minority Resident Hematology Award Program, N/A, not applicable.

For MMSAP, applicants must be enrolled in a MD or DO degree program. MMSAP provides a summer research experience after the first, second, or third year of medical school. Additionally, a “flexible” option allows for research to be conducted part-time over 12 months throughout the year during second, third, or fourth year of medical school. Finally, applicants can apply for a year-long option, which allows them to take 1 year off from medical school to engage in research full-time.

For MRHAP, applicants must be enrolled in an internal medicine, pathology, or pediatric residency program. Applicants must be within their first or second year of residency (pathology) or within the first 3 years of a 4-year residency program (internal medicine and pediatrics).

For MHFA, applicants must be within the first 2 years of a clinical fellowship or a postdoctoral position. Awardees are expected to spend at least 75% of their time on research activities for either a 2- or 3-year period.

For ASH-AMFDP, applicants must have completed the clinical portion of a hematology fellowship. Awardees are expected to spend at least 70% of their time on research activities with the support of a research mentor at their academic institution.

For MGSAAA, applicants must be within the first 5 years of a PhD or a combined MD-PhD or DO-PhD program and have an abstract accepted for oral or poster presentation at ASH annual meeting.

For MHGA, applicants must be within the first 3 years of a PhD program or have at least 2 years left in a combined MD-PhD or DO-PhD program. Awardees are expected to spend at least 65% to 75% of their time on research activities.

MRI awards eligibility

All trainee awards require the research mentor to be an ASH member and for the research to be conducted in the United States or Canada. For the medical student and resident awards, if the applicant is unable to identify a research mentor at their home institution, then they can request to be “matched” with an ASH research mentor at another institution. The matching process is performed by ASH member volunteers and ASH staff.

The early career award (ASH-AMFDP) eligibility criteria differ from the trainee awards. Unlike the trainee awards, the early career award does not require the research mentor to be an ASH member, and it only supports research conducted in the United States.

Additional eligibility criteria and respective award benefits can be found at https://www.hematology.org/awards.

Recruitment strategy

In the early years of the MRI, ASH advertised to dean’s and financial aid offices of accredited allopathic and osteopathic medical schools. Currently, ASH uses a variety of methods to encourage applicants to apply. Potential applicants and mentors are exposed to opportunities through ASH communication channels including social media (ASH website, X, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube), hematology news publications and emails to the ASH membership database. ASH also recruits from science, technology, and mathematics conferences focused on minority clinicians and scientists. ASH Ambassadors are encouraged to share opportunities with potential applicants at their home institutions. Additionally, prior promising applicants who did not receive funding are contacted and encouraged to reapply for the upcoming funding cycle. Nonetheless, the primary source of recruitment is from previous MRI mentors and past/current participants as they become unofficial program ambassadors. Active award recipients present their research experience during the annual meeting at a symposium. This event is the largest platform for recruiting mentors with >300 audience members, including National Institutes of Health (NIH) program officers, academic program chairs/chiefs, past awardees, and the president of ASH.

Study section

Awards are competitively selected through a rigorous review process modeled on the NIH study section and led by ASH member volunteers with relevant scientific expertise and understanding of program goals. This process includes adherence to the ASH conflict-of-interest policy. The review considers multiple aspects of each application including feasibility, innovation, and significance of the research proposal, the potential of the applicant, personal interest in hematology, likelihood of retention in the field of hematology, and the mentor/mentorship plan. The mentor’s demographic background is not part of the review discussion. Eligible applicants applying for a second year of funding are required to demonstrate productivity during their first year of funding, completion of all prerequisites from the prior cycle, and maintain the support of their research mentor to be competitive for additional funding.

Based on the American Association of Medical Colleges endorsement of holistic review as an effective strategy to recruit diverse applicants,13,14 most study sections use holistic review to allow for the consideration of experiences and personal attributes in addition to traditional metrics. Members of the study section are trained in the process. A driving criterion is the applicant’s likelihood of retention in the field of hematology as reflected in the personal statement and letters of recommendation. The “distance traveled” is also considered, recognizing that there may be distinct challenges that applicants have overcome and understanding that all persons are not given the same opportunities to thrive.

Training members of the study section in holistic review has evolved over time. Initially, the chair of the study section would describe the goal at the beginning of the study section and as needed during the study section. Currently, study section reviewers are emailed a short 5-minute video before the preliminary review process. The video not only emphasizes the goal of holistic review but also describes the impact of implicit bias.

Four awards (medical student, resident, fellow, and graduate student award) are decided over a 2-day study section. The graduate student abstract achievement award is decided separately during a half-day study section. The graduate student abstract achievement award study section uses the NIH scoring system; however, reviewers do not incorporate a holistic review of the application. Applicants are evaluated on their research potential, leadership, interest in hematology, and quality of their submitted abstract. The early career award selection is a multistep process. Applicants submit their research experience, career objectives, personal references, and a mentored training plan. Semifinalists are then selected for interviews that allow for the applicants to fully describe their research interests, institutional resources, and research environment.

Funding

In addition to funding received from ASH, ASH donors generously contribute to the ASH Foundation, and 100% of funds designated for MRI are used to extend the reach of the initiative.

Metrics of success

The short-term success of the medical and graduate student MRI awards was evaluated by comparing MRI graduation percentages with the national estimates of minority student graduation percentages. Short-term success was focused only on the medical student (2004-2018) and graduate student abstract achievement (2011-2017) awards because the other trainee awards were recently initiated, and recent awardees have not had time to graduate from their training programs. Long-term success was determined by continued engagement with ASH after their award and/or retention into hematology. Descriptively, continued engagement with ASH was evaluated for all MRI awardees. Retention in hematology was defined as being board eligible or board certified in hematology or hematology-oncology. This metric was evaluated for medical student (2004-2014 cohorts to allow time for the completion of education and fellowships) and early career, and it was compared with the national estimate of minority hematology-oncology faculty in academia.

Data collection

Data related to graduation and specialty areas was obtained online from publicly available information that was accessed from June to August 2023. Data related to engagement with ASH were obtained from ASH databases through November 2023.

Results

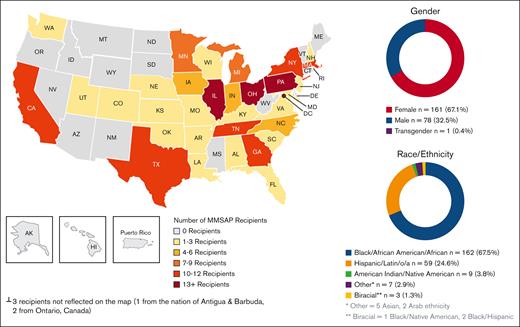

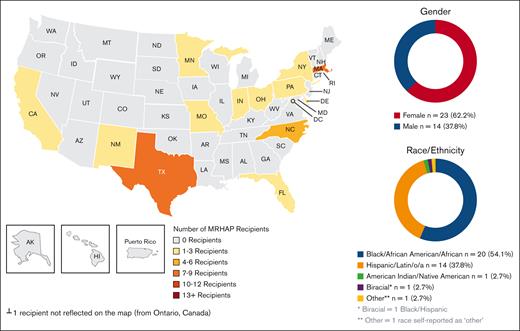

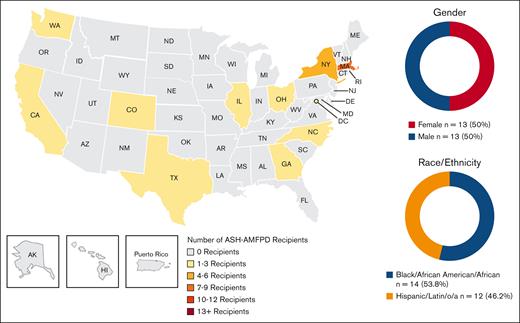

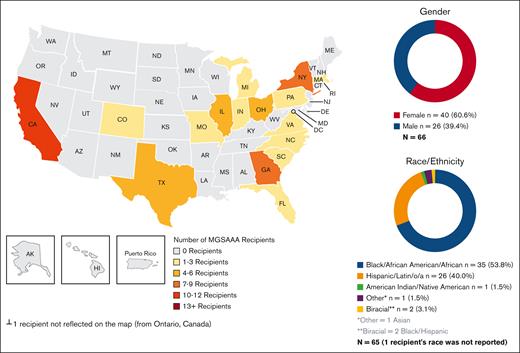

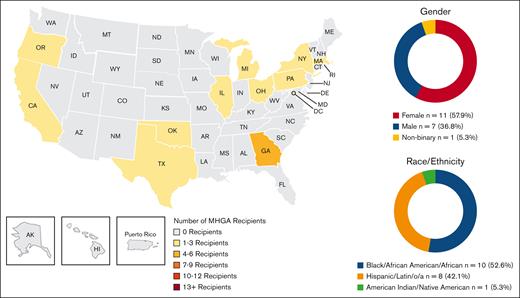

There were 405 individuals across the 6 awards programs from 2004 to 2022. The majority of these individuals received the medical student award (240 awardees from 2004 to 2022). Comparatively, the fellow and graduate student awards are the newest awards, and from 2020 to 2022, there were 17 and 19 recipients, respectively. Although the majority of awardees self-identified as Black (Figures 2-7), the early career, fellow, and graduate student awards had >40% of awardees identify as Hispanic/Latin/o/a/x (Figures 4, 5, and 7 respectively). For all awards, except the early career award, the majority of awardees self-identified as female (Figures 2-7). For the early career award, 13 of 26 (50%) identified as female, and 13 of 26 (50%) identified as male (Figure 5).

MMSAP, 2004-2022 (N = 240). MMSAP, Minority Medical Student Award Program.

MMSAP, 2004-2022 (N = 240). MMSAP, Minority Medical Student Award Program.

MRHAP, 2017-2022 (N = 37). MRHAP, Minority Resident Hematology Award Program.

MRHAP, 2017-2022 (N = 37). MRHAP, Minority Resident Hematology Award Program.

MHFA, 2020-2022 (N = 17). MHFA, Minority Hematology Fellow Award.

MHFA, 2020-2022 (N = 17). MHFA, Minority Hematology Fellow Award.

ASH-AMFDP, 2006-2022 (N = 26). ASH-AMFDP, American Society of Hematology Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program Award.

ASH-AMFDP, 2006-2022 (N = 26). ASH-AMFDP, American Society of Hematology Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program Award.

MGSAAA, 2011-2022 (N = 66). MGSAAA, Minority Graduate Student Abstract Achievement Award.

MGSAAA, 2011-2022 (N = 66). MGSAAA, Minority Graduate Student Abstract Achievement Award.

MHGA, 2020-2022 (N = 19). MHGA, Minority Hematology Graduate Award.

MHGA, 2020-2022 (N = 19). MHGA, Minority Hematology Graduate Award.

The majority of MRI recipients attended or were faculty (early career awardees) at an academic institution in the United States. Of all the awards, the medical student award has had the largest geographical reach (Figure 2). Notably, across the 6 different awards, there were 13 states that have never had a recipient (Arizona, Connecticut, Idaho, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming). Awardees also came from programs outside of the United States. At the time of the award, 2 medical student award recipients attended medical school in Canada, and 1 medical student award recipient attended medical school in the Caribbean (Figure 2). One resident award recipient was in a residency program in Canada at the time of the award (Figure 3), and 1 graduate student abstract achievement award recipient attended a doctoral program in Canada (Figure 6).

Outcomes

Medical school attrition was determined for the medical student cohorts from 2004 to 2018. During this time frame, there were 184 recipients; however, 3 were not evaluable (1 died, 1 currently in MD/PhD program, and 1 lost to follow-up). Of the 181 evaluable awardees, medical school attrition was 2.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61-5.6). Medical student awardees attrition from medical school was descriptively similar to the attrition reported for White non-Hispanic students (2.3%) although not statistically different from the reported underrepresented minority student attrition (5.6%).15 Notably, the 4 participants who did not graduate medical school all received advanced degrees (2 doctoral-level degrees and 2 master-level degrees).

Graduate school attrition was determined for graduate student abstract achievement cohorts from 2011 to 2017. Of the 32 recipients, graduate school attrition was 0% (1-sided 97.5% CI, 10.6). This was significantly lower than the 36% attrition reported for underrepresented minority doctoral students in science and engineering fields.16

The MRI provides longitudinal support and encourages recipients to stay on the pathway and apply for subsequent awards with the anticipated outcome of increased likelihood of retention in the field. Of the 77 individuals who received >2 MRI awards, 25 received progressive awards (ie, medical student awardee subsequently received a resident award).

Long-term outcomes were evaluated for medical student cohorts from 2004 to 2014. There were 97 board-eligible/board-certified awardees, and over half (55/97 [56.7%]) were currently in academic positions (ie, not currently in training). Furthermore, 14.4% (95% CI, 8.1-23.0) were board eligible or board certified in hematology (Table 2). Comparatively, only 5.7% of medical oncology faculty, which includes hematology-oncology, were considered underrepresented in medicine in 2019.11 Although not subspecialized in hematology, 1 medical student awardee (board certified in radiation oncology) presented a poster at the ASH annual meeting in 2021, demonstrating active engagement in hematology research. Inclusion of this participant would bring the medical student retention in hematology proportion to 15 of 97 or 15.5%, with 11 of 15 (73%) currently at academic institutions.

MMSAP awardees medical specialties (cohorts 2004-2014; N = 97)

| Board eligible/certified categories . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Hematology-oncology | 14 (14.4%) |

| Adult | 8 |

| Pediatrics | 5 |

| Hematopathology | 1 |

| Internal medicine/internal medicine subspecialty∗ | 14 (14.4%) |

| Emergency medicine | 12 (12.4%) |

| Anesthesiology | 11 (11.3%) |

| Surgery/surgery subspecialty∗ | 10 (10.3%) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 9 (9.3%) |

| Pediatrics/pediatric subspecialty∗ | 6 (6.2%) |

| Neurology | 5 (5.2%) |

| Family medicine | 4 (4.1%) |

| Dermatology | 4 (4.1%) |

| Psychiatry | 3 (3.1%) |

| Radiology | 2 (2.1%) |

| Radiation oncology | 1 (1.0%) |

| Pathology∗ | 1 (1.0%) |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | 1 (1.0%) |

| Board eligible/certified categories . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Hematology-oncology | 14 (14.4%) |

| Adult | 8 |

| Pediatrics | 5 |

| Hematopathology | 1 |

| Internal medicine/internal medicine subspecialty∗ | 14 (14.4%) |

| Emergency medicine | 12 (12.4%) |

| Anesthesiology | 11 (11.3%) |

| Surgery/surgery subspecialty∗ | 10 (10.3%) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 9 (9.3%) |

| Pediatrics/pediatric subspecialty∗ | 6 (6.2%) |

| Neurology | 5 (5.2%) |

| Family medicine | 4 (4.1%) |

| Dermatology | 4 (4.1%) |

| Psychiatry | 3 (3.1%) |

| Radiology | 2 (2.1%) |

| Radiation oncology | 1 (1.0%) |

| Pathology∗ | 1 (1.0%) |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | 1 (1.0%) |

MMSAP, Minority Medical Students Award Program.

Excluding hematology-oncology or hematopathology.

The majority of early career recipients (25/26 [96%]) remain in academia. Their specialties include the following: 14 (54%) in adult hematology; 6 (23%) in pediatric hematology; 3 (11.5%) in hematopathology; 1 (3.8%) in transfusion medicine; 1 (3.8%) in psychiatry; and 1 (3.8%) in pulmonary medicine. Overall, 23 of 26 or 88.5% (95% CI 70.0%, 97.6%) are practicing hematologists. This percentage is significantly greater than the 5.7% underrepresented minority faculty in medical oncology reported in national estimates in 2019.11

MRI alumni were actively engaged in hematology research beyond their MRI experience. From 2004 to 2022, 225 of 380 awardees (59%) were authors on 1105 ASH abstracts presented at the annual meeting (798 abstracts presented as poster presentations; 307 abstracts presented as oral presentations). This does not include any abstracts that may have been presented before the initial MRI award year.

MRI alumni also remain engaged in ASH through volunteer leadership roles. Forty-five alumni have served in 353 different roles, including reviewers on study sections, contributing editors for ASH publications, committee members, chairs of committees, and serving on the ASH executive committee (Table 3). Additionally, 42 of 234 individuals (18%) who no longer receive complementary ASH membership as a benefit of their award continue to renew their ASH membership.

ASH MRI alumni volunteer engagement, 2004-2022

| Types of volunteer roles∗ . | Count . |

|---|---|

| Program Service such as ASH MRI ambassador and ASH Advocacy Leadership Institute | 3 |

| Editorial volunteer (ASH journals Blood, Blood Advances, and The Hematologist) | 3 |

| Program faculty such as the ASH clinical research training institute faculty or meeting on hematologic malignancies faculty | 21 |

| Chair, cochair, director, or vice chair of an ASH committee | 29 |

| ASH study section reviewer | 131 |

| Membership on an ASH committee (including full member, ad hoc member, and liaison member) | 166 |

| Total | 353 |

| Types of volunteer roles∗ . | Count . |

|---|---|

| Program Service such as ASH MRI ambassador and ASH Advocacy Leadership Institute | 3 |

| Editorial volunteer (ASH journals Blood, Blood Advances, and The Hematologist) | 3 |

| Program faculty such as the ASH clinical research training institute faculty or meeting on hematologic malignancies faculty | 21 |

| Chair, cochair, director, or vice chair of an ASH committee | 29 |

| ASH study section reviewer | 131 |

| Membership on an ASH committee (including full member, ad hoc member, and liaison member) | 166 |

| Total | 353 |

Forty-five unique individuals have served in these various ASH volunteer roles.

Funding

ASH has invested more than $15 million to fund these experiences in hematology research since the MRI’s inception. This figure represents only award funds committed to recipients and does not include any other costs associated with programming or indirect costs associated with the initiative.

Discussion

What began in 2003 as a project of an ASH ad hoc committee has evolved into a longitudinal pathway of awards supporting individuals belonging to historically disadvantaged groups to become and remain involved in academic hematology. The ASH MRI program was built upon evidence-based best equity practices (ie, holistic file review, mentorship, and research stipends).5,6 In fact, studies have shown that academic institutions that use holistic review improve recruitment of targeted populations such as underrepresented minority students, female students, first-generation college students, and students from disadvantaged backgrounds.14

Success of the ASH MRI program is evident in the significantly lower graduate school attrition proportions for minority doctoral students than what would be expected (0% vs 36%) and minority medical school attrition percentages that were descriptively similar to those of White non-Hispanic medical students (2.2% vs 2.3%). Notably, 14.4% (95% CI, 8.1-23.0) of medical student awardees are now either board eligible or board certified in hematology, which is significantly greater than what would be expected (5.7% underrepresented medical oncology faculty). The early career award has been highly successful with 88.5% (95% CI, 70.0-97.6) of the awardees currently practicing as hematologists, and almost all (25/26 [96%]) remain in academia. Moreover, MRI alumni continued their engagement in hematology research after their award, as demonstrated by presenting research at the ASH annual meeting and volunteering with ASH.

Strengths of the MRI program include the longstanding financial commitment from ASH and ASH members. Additionally, ASH’s responsiveness to feedback from program alumni and mentors triggered the creation of additional awards to create a longitudinal pathway of support.

Outcomes related to medical specialties were obtained online from publicly available data. As a result, retention in hematology was limited to medical researchers who were either board eligible or board certified in hematology. This approach resulted in a conservative estimate of retention in hematology because there are researchers who are not board eligible or certified in hematology but are still actively engaged in hematology. Additionally, because doctoral researchers do not undergo certification, we were unable to assess the retention in hematology for these researchers. Another limitation of the evaluation was selecting the appropriate comparison group because there were not published estimates of underrepresented practicing hematologists outside of faculty at academic institutions.

Future directions include implementing a standard annual assessment tool for all MRI awardees, which will allow for the long-term tracking of the outcomes of interest. Our next steps also include a formal mixed methods assessment to elucidate the impact of the award on one’s career. A subset of awardees from each program will be interviewed using the social cognitive career theory as a conceptual framework to understand how experiences in the program influenced their academic/career choices and affected their self-efficacy. To support the states who have not yet had an MRI awardee, next steps include the identification of local active ASH members who could act as ambassadors for the MRI program. As mentioned previously, in 2018, the ASH Ambassador Program was created to help improve the geographical diversity of MRI applicants, but we do not have an ambassador in every state yet. In summary, the ASH MRI program has provided research opportunities for members of historically disadvantaged populations while having the foresight to address the barriers that have traditionally prevented these individuals from leveraging research opportunities and awards (ie, provided stipends, annual travel bursaries to attend meetings, and mentoring, etc). ASH is the only society that offers a longitudinal pathway of support for both medical and doctoral researchers who identify as underrepresented minorities. This initiative serves as just 1 facet in the ASH commitment to advancing health equity for individuals affected by blood disorders. ASH continues to stand for diversity, equity, and inclusion in a climate in which diversity, equity, and inclusion are sometimes under threat.17 As long as racial disparities in health care exist, committed efforts from ASH and other societies are necessary to improve the outcomes of patients. ASH supports underrepresented individuals in hematology and strives to evaluate and dismantle the causes of inequitable health outcomes for those affected by blood disorders. This is achieved through programs such as the MRI, as well as clinically focused work that includes reconsidering the use of race as a proxy for biologic and genetic differences in all areas of hematology-oncology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the donors to the ASH Foundation and the staff of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) for all they do to support the operations of these programs.

D.R.T. was supported by National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI]) grant 1K01HL135466. M.S. reports research support from the following funding sources: Be The Match Foundation Amy Strelzer Manasevit Research Program, Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (Clinical Investigator Award), V Foundation (V Scholar), Emerson Collective, and the National Institutes of Health/NHLBI grant K08 HL156082-01A1. C.R.F. received support from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR190079), where he is a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Scholar in Cancer Research. R.H.R. reports research support from National Institutes of Health grants 1P20CA284971-01 and P50 CA126752, National Cancer Institute Cancer Clinical Investigator Team Leadership Award, Be The Match Foundation Amy Strelzer Manasevit Research Program, Stand Up To Cancer, ASH–Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program, and Lymphoma Research Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: D.R.T. performed data cleaning and analysis; R.M.W. created the figures and visual abstract; and all authors conceived and designed the study, participated in data collection, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.H.R. reports consulting fees from Pfizer; honoraria from Novartis; and has received research funding from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. R.H.R., M.R.R., and M.S. are past MRI recipients. M.R.R., M.S., R.M.W., A.M., R.H.R., B.R.A., C.S.J., J.A.L., A.A.T., C.R.F., and D.R.T. are all past or current members of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Committee on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. L.F., P.F., K.R., and N.v.H. were employed by the ASH at the time of manuscript preparation. D.M. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Deirdra R. Terrell, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, 801 NE 13th St, Hudson College of Health Building, Room 333, Oklahoma City, OK 73104; email: dee-terrell@ouhsc.edu.

References

Author notes

M.R.R. and R.M.W. are joint first authors.