Key Points

Recent guidelines have recommended a more limited role for primary prevention aspirin, which can increase bleeding risk.

Many patients remain on primary prevention aspirin contrary to guideline recommendations, suggesting a need for deprescribing.

Visual Abstract

Recent guidelines have recommended a reduced role for primary prevention aspirin use, which is associated with an increased bleeding risk. This study aimed to characterize guideline-discordant aspirin use among adults in a community care setting. As part of a quality improvement initiative, patients at 1 internal medicine and 1 family medicine clinic affiliated with an academic hospital were sent an electronic survey. Patients were included if they were at least 40 years old, had a primary care provider at the specified site, and were seen in the last year. Patients were excluded if they had an indication for aspirin other than primary prevention. Responses were collected from 15 February to 16 March 2022. Analyses were performed to identify predictors of primary prevention aspirin use and predictors of guideline-discordant aspirin use; aspirin users and nonusers were compared using Fisher exact test, independent samples t tests, and multivariable logistic regression. Of the 1460 patients sent a survey, 668 (45.8%) responded. Of the respondents, 132 (24.1%) reported aspirin use that was confirmed to be for primary prevention. Overall, 46.2% to 58.3% of primary prevention aspirin users were potentially taking aspirin, contrary to the guideline recommendations. Predictors of discordant aspirin use included a history of diabetes mellitus and medication initiation by a primary care provider. In conclusion, primary prevention aspirin use may be overutilized and discordant with recent guideline recommendations for approximately half of the patients, suggesting a need for aspirin deimplementation. These efforts may be best focused at the primary care level.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. Aspirin has an established role in the secondary prevention of CVD, as the antithrombotic benefit is generally considered to be greater than the added risk of bleeding. The use of aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD, however, has been a longstanding source of debate, with shifting perspectives over the years.1 Most recently in 2022, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended an individualized approach to aspirin initiation in patients aged 40 to 59, and against initiation in adults ≥60 years.2 These recommendations rely partially on modeling data that suggest a net harm when starting aspirin with advancing age.3,4 As the net benefit likely decreases in a similar way for patients who already take aspirin, data suggest that it is reasonable to consider stopping around age 75.2

The recent USPSTF guidelines (2022) largely echo the 2019 recommendations from the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA), which recommend against using primary prevention aspirin on a routine basis for adults >70 years old or those at increased risk of bleeding.5 They report that aspirin can be considered for adults aged 40 to 70 who have increased CVD risk but do not have increased bleeding risk.5 Both of these updated guidelines reflect findings from recent large, randomized control trials such as Aspirin to Reduce Risk of Initial Vascular Events,6 A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes,7 and Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly,8 which together suggest that the potential benefits of aspirin for primary prevention of CVD may be offset by increased bleeding. Both Raber et al1 and Khan et al9 effectively summarize the trial data and meta-analyses that inform the latest aspirin guidelines. With significant advances in blood pressure control, smoking cessation, and lipid management, it is possible that there is a diminished role for primary prevention aspirin use in modern health care.1,9 Indeed, other international guidelines have come to similar conclusions on primary prevention aspirin use (Table 1).10,11

A summary of recent guidelines for aspirin for primary prevention

| Organization/society . | Year . | Select discussion regarding aspirin for primary prevention . |

|---|---|---|

| USPSTF2 | 2022 | Consider in adults aged 40-59 y with increased ASCVD risk on an individual basis. Persons not at increased risk of bleeding are more likely to benefit Recommend against initiation in adults >60 y It may be reasonable to consider stopping aspirin use around age 75 years. |

| ACC/AHA5 | 2019 | Consider in select adults aged 40-70 with higher ASCVD risk and without increased bleeding risk Should not be given routinely to adults aged >70. |

| European Society of Cardiology10 | 2021 | Should not be given routinely to patients without established ASCVD Cannot exclude that in some patients at high cardiovascular risk, benefits may outweigh risks. Can consider aspirin for primary prevention for patients with diabetes mellitus and high or very high CVD risk. |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society11 | 2023 | Recommend against routine use, regardless of sex, age, or diabetes. Aspirin may be appropriate for those with high ASCVD risk and low bleeding risk through a shared decision-making process. |

| American Diabetes Association12 | 2023 | Consider in diabetics at increased cardiovascular risk after discussing the comparable increase in bleeding risk For those with diabetes and established ASCVD, use aspirin for secondary prevention. |

| Organization/society . | Year . | Select discussion regarding aspirin for primary prevention . |

|---|---|---|

| USPSTF2 | 2022 | Consider in adults aged 40-59 y with increased ASCVD risk on an individual basis. Persons not at increased risk of bleeding are more likely to benefit Recommend against initiation in adults >60 y It may be reasonable to consider stopping aspirin use around age 75 years. |

| ACC/AHA5 | 2019 | Consider in select adults aged 40-70 with higher ASCVD risk and without increased bleeding risk Should not be given routinely to adults aged >70. |

| European Society of Cardiology10 | 2021 | Should not be given routinely to patients without established ASCVD Cannot exclude that in some patients at high cardiovascular risk, benefits may outweigh risks. Can consider aspirin for primary prevention for patients with diabetes mellitus and high or very high CVD risk. |

| Canadian Cardiovascular Society11 | 2023 | Recommend against routine use, regardless of sex, age, or diabetes. Aspirin may be appropriate for those with high ASCVD risk and low bleeding risk through a shared decision-making process. |

| American Diabetes Association12 | 2023 | Consider in diabetics at increased cardiovascular risk after discussing the comparable increase in bleeding risk For those with diabetes and established ASCVD, use aspirin for secondary prevention. |

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Only abbreviated guideline recommendations are presented in this table. Please see the referenced articles for full guideline recommendations and the associated discussion.

Although guidelines regarding aspirin use for primary prevention continue to become more conservative,1 the implementation of these guidelines as part of routine patient care remains uncertain. Overutilization of aspirin has been a long-recognized problem, suggesting a need for active intervention to improve guideline-concordant care.13 This is especially important because 25% to 45% of adults aged >40 years use aspirin for primary prevention.14-16 Meta-analyses of the available data suggest that millions of patients may be at risk of net harm from unnecessary aspirin therapy.17-19

To improve the appropriate use of aspirin for primary prevention, we sought to determine the prevalence and correlates of guideline-concordant aspirin use among adults in a community care setting now several years after the publication of the updated guidelines. Specifically, we examined patient characteristics, aspirin indications, prescribing physicians, and perceived risks and benefits.

Methods

Design and participants

An electronic survey was sent to the patients via the electronic health record (EHR) patient portal as part of a broader quality improvement project. Patients were included if they were at least 40 years old and had a primary care provider (PCP) at 2 academic hospital-affiliated clinics, 1 family medicine clinic, and 1 internal medicine clinic. The selected clinics were faculty-run and did not routinely include trainees in patient care. Patients were excluded if they had a documented indication for aspirin use other than primary prevention of CVD in the active problem list, past medical history, or past surgical history sections of the EHR. Patient comorbidities and medications were also assessed using the EHR to determine the guideline concordance of aspirin use. The study was considered exempt from Institutional Review Board review, and patient consent was not required.

Survey design

The survey was developed and validated with input from patients, PCP, hematologists, cardiologists, pharmacists, and experts in quality improvement and the survey methodology. It was revised through multiple rounds of pilot testing with patient advisors from the Michigan Medicine Office of Patient Experience who provided feedback on the clarity of the questions and ease of completion. Feedback was obtained from the University of Michigan Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine.

Overall, the survey (supplemental Data) inquired about the strength and frequency of aspirin use, reasons for taking aspirin, medical history, and bleeding risk using 11 multiple-choice questions. Patients could additionally answer several optional questions, including 2 open-ended questions about the perceived risk and benefit of aspirin use and a self-rating of overall health, using a Likert scale. The methods of the survey have previously been described.20 If there was a discrepancy between a patient's self-reported aspirin use and the EHR medication list, a notification was sent to the PCP for reconciliation. Survey responses were collected >30 days. No compensation was provided for the respondents, and no reminders or follow-up notices were given.

Primary prevention aspirin use was defined as taking any dose of aspirin most days of the week in patients without a history of the following: myeloproliferative neoplasms, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, atrial fibrillation/flutter, myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, carotid artery disease, Lynch syndrome, multiple myeloma, venous thromboembolic disease, percutaneous coronary intervention or bypass grafting, vascular stenting, heart valve replacement, heart transplant, cardiac arrhythmia, pre-eclampsia, strokes, and/or transient ischemic attacks. Patients on aspirin with a reported history of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease were classified as secondary prevention aspirin users. Notably, the survey was only sent to patients who appeared to be taking aspirin for primary prevention based on the medication list, past medical history, past surgical history, and problem list sections of the EHR. For example, the survey would not have been sent to a patient with coronary artery disease documented in their problem list.

Analysis

To determine patients who might be using aspirin, contrary to guideline recommendation, we assessed multiple factors. The first was age, including patients beyond age 75 per the USPSTF2 and age 70 per the ACC/AHA.5 Secondly, we assessed patients potentially at increased risk of bleeding based on regular use of certain medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anticoagulants, or nonaspirin antiplatelets. Additionally, we included patients with a history of hospital admission involving a primary bleeding diagnosis within 2 years of the study period.21 Finally, a history of frequent falls, liver or kidney disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, gynecological bleeding, genitourinary bleeding, peptic ulcer disease, and/or heavy alcohol use qualified a patient for potential guideline-discordant aspirin use. These bleeding risk factors were selected because they were either specifically mentioned by recent aspirin guidelines or are otherwise established in patients on antithrombotic therapy.2,5,21 We did not evaluate risk factors that have significant overlap with CVD risk, such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension.22

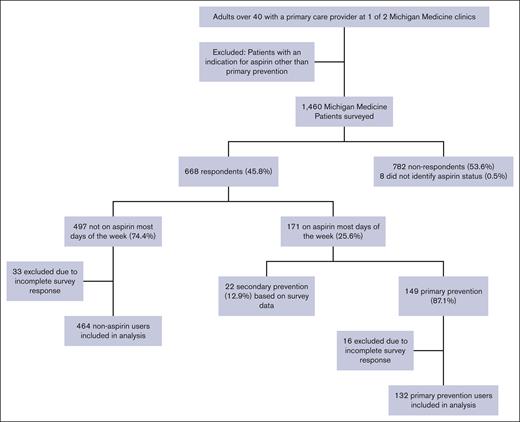

The analysis summarized categorical variables with frequencies and percentages, and compared aspirin users and aspirin nonusers using Fisher exact test. It summarized continuous variables using means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges, as appropriate, and compared aspirin users and aspirin nonusers using independent sample t tests. Two separate regression analyses were performed: (1) to identify predictors of primary prevention aspirin use and (2) to determine predictors of guideline-discordant aspirin use. The dependent variables for the multivariable logistic regression models were discordant aspirin use in primary prevention patients and aspirin use for primary prevention. The independent variables in the discordant aspirin use model were sex, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, medication use, and initiating provider. The aspirin use for primary prevention model focused on age, sex, BMI, medication use, and comorbidities. The analyses used data from both the EHR and the survey of aspirin users. Patients were excluded from the regression if they did not complete all the survey questions (Figure 1). All analyses were performed using Stata MP17 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This project was determined to be exempt from review by the University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board as part of a quality improvement project.

Results

Of the 1460 patients sent surveys, 45.8% (668/1460) responded. Sixteen primary prevention aspirin users and 33 nonaspirin users were excluded from our analysis because of incomplete survey data (Figure 1; Table 2). Of the respondents, 24.1% (132/619) reported aspirin use confirmed to be for primary prevention. This group included 82 men (62.1%) with a median (standard deviation) age of 64.8 (8.1) years, with sex defined by the EHR.

Patient characteristics

| . | Aspirin users (n = 132) . | Aspirin nonusers (n = 464) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age mean (SD) | 64.8 (8.1) | 61 (10.6) | <.001 |

| Sex, female | 50 (37.9%) | 295 (63.6%) | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| White or Caucasian | 113 (85.6%) | 411 (88.6%) | .10 |

| Black or African American | 5 (3.8%) | 26 (5.6%) | |

| Asian | 7 (5.3%) | 19 (4.1%) | |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 2 (1.5%) | 5 (1.1%) | |

| Patient refused | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (0.4%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 41 (31.1%) | 44 (9.5%) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 83 (62.9%) | 178 (38.4%) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (6.1%) | 21 (4.5%) | .49 |

| CHF | 3 (2.3%) | 10 (2.2%) | 1.00 |

| OSA | 36 (27.3%) | 110 (23.7%) | .42 |

| Anemia | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | .01 |

| Cirrhosis/liver disease | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | .22 |

| BMI mean (SD) | 31 (5.8) | 29.5 (6.3) | .04 |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Current | 5 (3.8%) | 28 (6%) | .34 |

| Former | 46 (34.8%) | 183 (39.4%) | |

| Never | 81 (61.4%) | 253 (54.5%) | |

| Heavy alcohol use | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | .01 |

| Medication characteristics | |||

| Aspirin on medication list | 108 (81.8%) | 61 (13.1%) | <.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Celecoxib | 2 (1.5%) | 14 (3.0%) | .54 |

| Rivaroxaban, apixaban, low molecular weight heparin | 2 (1.5%) | 12 (2.6%) | .75 |

| NSAID EHR | 29 (22%) | 232 (50%) | <.001 |

| NSAID self-report | 19 (14.4%) | — | — |

| Aspirin use past 2 wk | — | — | |

| 11-14 d | 116 (87.9%) | — | — |

| 7-10 d | 13 (9.8%) | — | — |

| 4-6 d | 3 (2.3%) | — | — |

| Years of aspirin use | — | — | |

| 0-2 y | 15 (11.4%) | — | — |

| 3-5 y | 21 (15.9%) | — | — |

| 6-10 y | 40 (30.3%) | — | — |

| 11-20 y | 34 (25.8%) | — | — |

| >20 y | 22 (16.7%) | — | — |

| Dose ≤81 mg | 117 (89.3%) (n = 131) | — | — |

| Initiating provider | — | — | |

| PCP | 83 (62.9%) | — | — |

| Self | 21 (15.9%) | — | — |

| Cardiology | 11 (8.3%) | — | — |

| Specialist (other than cardiology) | 10 (7.6%) | — | — |

| Recommendation of family or friend | 4 (3.0%) | — | — |

| Other | 3 (2.3%) | — | — |

| Admission related to bleeding | 19 (14.4%) | 54 (11.6%) | .45 |

| Major bleeding (self-report) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | .22 |

| Falls | 6 (4.6%) | — | — |

| Heartburn | 21 (15.9%) | — | — |

| Peptic ulcer | 2 (1.5%) | — | — |

| Rating of overall health (Median and IQR) | 8 [7-8] | — | — |

| . | Aspirin users (n = 132) . | Aspirin nonusers (n = 464) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age mean (SD) | 64.8 (8.1) | 61 (10.6) | <.001 |

| Sex, female | 50 (37.9%) | 295 (63.6%) | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| White or Caucasian | 113 (85.6%) | 411 (88.6%) | .10 |

| Black or African American | 5 (3.8%) | 26 (5.6%) | |

| Asian | 7 (5.3%) | 19 (4.1%) | |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 2 (1.5%) | 5 (1.1%) | |

| Patient refused | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (0.4%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 41 (31.1%) | 44 (9.5%) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 83 (62.9%) | 178 (38.4%) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (6.1%) | 21 (4.5%) | .49 |

| CHF | 3 (2.3%) | 10 (2.2%) | 1.00 |

| OSA | 36 (27.3%) | 110 (23.7%) | .42 |

| Anemia | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | .01 |

| Cirrhosis/liver disease | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | .22 |

| BMI mean (SD) | 31 (5.8) | 29.5 (6.3) | .04 |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Current | 5 (3.8%) | 28 (6%) | .34 |

| Former | 46 (34.8%) | 183 (39.4%) | |

| Never | 81 (61.4%) | 253 (54.5%) | |

| Heavy alcohol use | 3 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | .01 |

| Medication characteristics | |||

| Aspirin on medication list | 108 (81.8%) | 61 (13.1%) | <.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Celecoxib | 2 (1.5%) | 14 (3.0%) | .54 |

| Rivaroxaban, apixaban, low molecular weight heparin | 2 (1.5%) | 12 (2.6%) | .75 |

| NSAID EHR | 29 (22%) | 232 (50%) | <.001 |

| NSAID self-report | 19 (14.4%) | — | — |

| Aspirin use past 2 wk | — | — | |

| 11-14 d | 116 (87.9%) | — | — |

| 7-10 d | 13 (9.8%) | — | — |

| 4-6 d | 3 (2.3%) | — | — |

| Years of aspirin use | — | — | |

| 0-2 y | 15 (11.4%) | — | — |

| 3-5 y | 21 (15.9%) | — | — |

| 6-10 y | 40 (30.3%) | — | — |

| 11-20 y | 34 (25.8%) | — | — |

| >20 y | 22 (16.7%) | — | — |

| Dose ≤81 mg | 117 (89.3%) (n = 131) | — | — |

| Initiating provider | — | — | |

| PCP | 83 (62.9%) | — | — |

| Self | 21 (15.9%) | — | — |

| Cardiology | 11 (8.3%) | — | — |

| Specialist (other than cardiology) | 10 (7.6%) | — | — |

| Recommendation of family or friend | 4 (3.0%) | — | — |

| Other | 3 (2.3%) | — | — |

| Admission related to bleeding | 19 (14.4%) | 54 (11.6%) | .45 |

| Major bleeding (self-report) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | .22 |

| Falls | 6 (4.6%) | — | — |

| Heartburn | 21 (15.9%) | — | — |

| Peptic ulcer | 2 (1.5%) | — | — |

| Rating of overall health (Median and IQR) | 8 [7-8] | — | — |

All data from the patient survey apart from admission related to bleeding, comorbidities other than cirrhosis and anemia, demographics, and concomitant medications (aspirin and NSAIDs) were reviewed by the medical records and the survey. Data not provided by the patient surveys were identified from the EHR.

CHF, congestive heart failure; IQR, interquartile range; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PCP, primary care provider; SD, standard deviation.

Among primary prevention aspirin users, 87.9% (116/132) had taken it 11 to 14 days in the past 2 weeks, 89.3% (117/131) were on a dose of ≤81 mg per day, and 72.7% (96/132) had been on it for >5 years. Additionally, 62.9% (83/132) reported that their PCP suggested taking aspirin, 15.9% (21/132) started aspirin on their own, 8.3% (11/132) took aspirin at the suggestion of a cardiologist, 7.6% (10/132) took aspirin because of the recommendation of another doctor, and 5.3% (7/132) had another reason for taking aspirin (Table 2). Dosing data were not available for 1 patient who otherwise completed the survey.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that primary prevention aspirin was more commonly used when aspirin was included in the medication list (odds ratio [OR], 45; 95% confidence interval [CI], 20-110; P < .001) and among male patients (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.3-5.3; P = .007). Other factors were not associated with the use of primary prevention aspirin use.

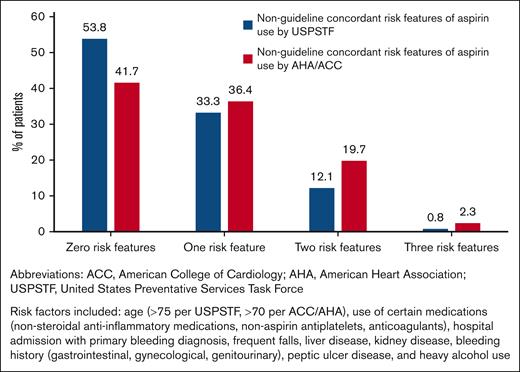

Overall, 46.2% to 58.3% (61-77/132) of primary prevention aspirin users were potentially inconsistent with the guidelines, with the range accounting for discrepant age recommendations between USPSTF2 and ACC/AHA5 (Table 3; Figure 2). Possible reasons for guideline-discordant aspirin use included comorbidities that increased the risk of bleeding (falls, alcohol use, kidney disease, peptic ulcer disease, and others; 37.1%), concomitant use of other NSAIDs (31.8%), concomitant use of anticoagulants (1.5%), advanced age (30.3% age >70 years, 7.6% age >75 years), and a history of hospitalization with a primary bleeding diagnosis (13.6%).

Incidence of bleeding risk factors among respondents (n = 132)

| Bleeding risk factors . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age >70 | 40 (30.3) |

| Age >75 | 10 (7.6) |

| Concurrent NSAID use | 42 (31.8) |

| Ibuprofen | 21 (15.9) |

| Naproxen | 4 (3) |

| Meloxicam | 3 (2.3) |

| Indomethacin | 2 (1.5) |

| Unspecified | 13 (9.8) |

| Concurrent antiplatelet or anticoagulant use | 2 (1.5) |

| Comorbidities | 49 (37.1) |

| Admission with a bleeding diagnosis | 18 (13.6) |

| Genitourinary bleeding | 10 (7.6) |

| Gynecologic bleeding | 6 (4.5) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 2 (1.5) |

| Renal failure | 8 (6.1) |

| History of falls | 6 (4.5) |

| Anemia | 3 (2.3) |

| Heavy alcohol use | 3 (2.3) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 2 (1.5) |

| History of gastrointestinal bleed | 1 (0.8) |

| Liver disease/cirrhosis | 1 (0.8) |

| Bleeding risk factors . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Age >70 | 40 (30.3) |

| Age >75 | 10 (7.6) |

| Concurrent NSAID use | 42 (31.8) |

| Ibuprofen | 21 (15.9) |

| Naproxen | 4 (3) |

| Meloxicam | 3 (2.3) |

| Indomethacin | 2 (1.5) |

| Unspecified | 13 (9.8) |

| Concurrent antiplatelet or anticoagulant use | 2 (1.5) |

| Comorbidities | 49 (37.1) |

| Admission with a bleeding diagnosis | 18 (13.6) |

| Genitourinary bleeding | 10 (7.6) |

| Gynecologic bleeding | 6 (4.5) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 2 (1.5) |

| Renal failure | 8 (6.1) |

| History of falls | 6 (4.5) |

| Anemia | 3 (2.3) |

| Heavy alcohol use | 3 (2.3) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 2 (1.5) |

| History of gastrointestinal bleed | 1 (0.8) |

| Liver disease/cirrhosis | 1 (0.8) |

Percentage of patients with potentially non-guideline concordant features among primary prevention aspirin users.

Percentage of patients with potentially non-guideline concordant features among primary prevention aspirin users.

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, the predictors of guideline-discordant aspirin use included a history of diabetes mellitus (OR, 140; 95% CI, 12-6700; P = .002). Guideline-discordant aspirin use was less likely if aspirin was initiated by the patients themselves or at the recommendation of a family member or friend compared with their PCP (OR, 0.03; 95% CI, 0.001-0.4; P = .023). Guideline-discordant aspirin use was also less likely if aspirin was started by a specialist than PCP (OR, 0.021; 95% CI, 0.001-0.28; P = .014). Other factors, including BMI, medication list accuracy, use of gastrointestinal prophylaxis, comorbidities, and NSAID use, were not associated with aspirin use.

Overall, patients had positive perceptions of the benefits of aspirin, reporting that they thought aspirin could reduce their risk of the following: heart attack (100/132, 76%), stroke or transient ischemic attack (80/132, 60%), colon cancer (14/132, 11%), and dementia (4/132, 3%). They also reported that aspirin improved their general health (22/132, 17%) and pain management (20/132, 15%) (Table 4). Of the 72 patients providing free response answers to concerns they had about aspirin use, 18 (43.2%) expressed they had none, and 16 (22.2%) wrote in questions about aspirin. Most patients did not express concerns about bleeding due to aspirin use.

Patient perceptions of primary prevention aspirin use

| Perceived benefits of aspirin . | N (% of respondents) . |

|---|---|

| Reduced risk of heart attack | 100 (75.8%) |

| Reduced risk of stroke or transient ischemic attack | 80 (60.1%) |

| Improved general health | 22 (16.7%) |

| Improved pain | 20 (15.2%) |

| Reduced risk of colon cancer | 14 (10.6%) |

| Reduced risk of dementia | 4 (3.0%) |

| Other health benefits | 4 (3.0%) |

| Perceived benefits of aspirin . | N (% of respondents) . |

|---|---|

| Reduced risk of heart attack | 100 (75.8%) |

| Reduced risk of stroke or transient ischemic attack | 80 (60.1%) |

| Improved general health | 22 (16.7%) |

| Improved pain | 20 (15.2%) |

| Reduced risk of colon cancer | 14 (10.6%) |

| Reduced risk of dementia | 4 (3.0%) |

| Other health benefits | 4 (3.0%) |

Discussion

This survey identified that primary prevention aspirin use remains pervasive, with ∼1 in 4 adults taking aspirin for this indication. Aspirin was more commonly used among patients identified as male in the EHR. Overall, 46.2% to 58.3% of survey-responding patients were using aspirin in a way that may be inconsistent with the guideline recommendations. Potential overuse of aspirin was associated with a history of diabetes mellitus as well as PCP management of the medication. Patients perceived multiple benefits of aspirin, and most did not endorse bleeding as a potential concern when answering open-ended questions (data not shown). Our survey suggests that PCPs play a central role in aspirin management, as 63% of respondents reported that their PCPs advised starting medication. The results suggest there may be opportunities to improve guideline-concordant aspirin use. Notably, patients who indicated that they took aspirin <3 days per week were included as nonusers, given that our focus was on regular primary prevention aspirin users.

The survey was itself used as a tool for helping implement aspirin guidelines. Results were used for subsequent medication reconciliation and to alert providers of potential guideline-discordant aspirin use among their patients. Although the EHR was used to target primary prevention aspirin users as the sole recipients of the survey, 12.9% of the survey respondents reported aspirin for secondary prevention. Furthermore, aspirin was accurately documented in the EHR for 81.9% of primary prevention aspirin users, suggesting that approximately one-fifth of primary prevention aspirin users were not identified using our methods in the EHR.20 Taken together, these findings suggest a need to improve the methods used to identify primary prevention aspirin users. Specifically, reconciling aspirin in EHR may be important for efforts to improve the quality of aspirin therapy.

The potential overuse of aspirin was associated with a history of diabetes mellitus, which remains a known risk factor for CVD.5 However, it is worth noting that A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes trial identified that in patients with diabetes taking aspirin for primary prevention, the absolute risk reduction in cardiovascular events was offset by a similar absolute risk increase in major bleeding.7 Therefore, guidelines continue to recommend that diabetic patients receive primary prevention aspirin on a limited basis; the presence of this disease does not necessarily strengthen the recommendation to use aspirin for this purpose.2,5,22 Our results emphasize that patients with diabetes are more likely to be using aspirin in a guideline-discordant manner, and this population warrants special consideration when determining the appropriateness of aspirin use.

It is also important to note the distinction between initiating and stopping aspirin for primary prevention. A patient who has never taken aspirin might have a higher bleeding risk with its initiation than a patient who has established a longstanding tolerance. Some secondary analyses of trial-level data have suggested that aspirin discontinuation for primary prevention may be associated with a higher risk of subsequent cardiovascular events without reducing bleeding risk.23 Further studies may be necessary to establish if aspirin deprescribing should be handled differently than aspirin prescribing.

Our survey provides modern data on aspirin dosing in a primary-prevention cohort. Approximately 10% of primary prevention aspirin users took full-dose aspirin, potentially relating to ∼15% of respondents taking aspirin for pain management. Aspirin doses of ≤100 mg per day are similarly effective for primary prevention compared with higher doses.2 Although there are limited comparative data on various aspirin regimens, lower doses of aspirin may be associated with a lower risk of bleeding.24,25 There may be an opportunity to reduce the dose of aspirin in patients on full dose as a means to lower the bleeding risk profile when aspirin is continued. Although the analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of aspirin are realized at higher doses,26,27 it is possible that patients using aspirin for analgesic purposes may benefit from other treatment strategies.

Our survey results additionally emphasize the central role that PCP has in managing primary prevention of aspirin use, having initiated it for most patients. Somewhat concerning is our finding that approximately one-fifth of patients took aspirin without the recommendation of a health care professional, a finding similar to that identified in previous studies.28 Additionally, aspirin use was also more likely to be guideline-concordant among patients initiating aspirin on their own or at the recommendation of a family member or friend compared with their PCP. This may reflect changes in guideline use recommendations over time, aspirin uses not being reassessed during follow-up (so-called “clinical inertia”), competing concerns at subsequent appointments, or patient self-adjustments based on information obtained from other sources. We also observed that guideline-discordant use was more common in patients who discussed aspirin use with their PCP than with a specialist. This may be because specialists have greater knowledge or time to address aspirin use. Another possibility is that patients followed by specialists may have a distinct health profile compared with those who do not. They may be more likely to receive guideline-concordant care as a result.

When asked about how aspirin could be helpful to them, several patients listed taking aspirin to follow through on the advice of their PCP. Notably, nearly one-fourth of the respondents did not indicate bleeding as a concern with primary prevention aspirin use, and 1 in 10 had questions regarding whether they should even be taking it. This information should encourage physicians to engage patients on their aspirin use as a part of routine care. Considering the mixed primary care guidance on how to apply aspirin guidelines29 and the stability of primary prevention aspirin use over time, we suspect that an active deprescribing intervention will be needed to improve guideline concordance.

Limitations to this survey include those inherent to cross-sectional survey design. Although the response rate was relatively high for an electronic survey sent once without follow-up communication, there is a potential for response bias, as in all survey studies. Given that the results were shared with care teams, social desirability bias is possible, as patients may want to demonstrate adherence to providers' suggestions. Respondents were similar to nonrespondents with respect to sex, BMI, and aspirin use as documented in the EHR; however, respondents were more often white and older than nonrespondents.20 Patients with the capability to complete an electronic survey through the patient portal may differ from those who do not use the patient portal. It is possible that respondents are more likely to receive guideline-concordant therapy based on their increased engagement with the health care system, particularly in a well-educated area surrounding a large university. It is also possible that respondents who are more concerned about their health and engaged in health care are more likely to take a preventative drug due to perceived benefits compared with nonrespondents, who may be less engaged in their health. Ultimately, a larger and more diverse patient sample would be desirable in future studies to confirm our findings. This study was limited to 2 primary care clinics affiliated with a single large university medical center. Although these clinics are similar to community clinics and do not routinely involve trainees, it would also be desirable to confirm these findings in other clinical settings.

To define guideline-discordant aspirin use, both age and bleeding risk factors were used, which rely on the accuracy of the EHR. Medications available over the counter, such as NSAIDs, may not be accurately recorded.19,30 Furthermore, although guidelines2,5 identify NSAID use as a potential bleeding risk factor, it is unclear what degree of exposure is clinically significant. We defined NSAID use as "most days of the week" in the survey (supplemental Data) or if listed on the medication list (largely including prescription NSAIDs); however, future studies should determine if there is a safe level for aspirin users. Although it is possible that NSAID use and other bleeding risk factors were misclassified, we suspect the risk of this is low based on our use of a combination of patient report and chart review, assessing institutional hospitalization data, and medication lists. Overall, this process is similar to how a provider may assess aspirin use for a new patient.

Through this survey of adult patients receiving primary care in the community setting, we identified several gaps in the use of primary prevention aspirin. First, it is challenging to identify patients on aspirin, given the limitations in identifying primary vs secondary prevention and variable medication documentation for this over-the-counter medication. Second, the patients overestimate the benefit relative to the risks of primary prevention aspirin use. Third, some patients do not discuss this medication with their health care professionals, and several patients questioned whether they should truly be taking it. We suggest that clinicians and their teams encourage patients to report their aspirin use. PCPs may be supported by their specialist colleagues in this effort, and hematologists may play a central role given the importance of antithrombotic stewardship, which has been increasingly recognized within system-based hematology. We recommend that providers closely monitor the aspirin status of their patients, assess if its use is appropriate, and engage in shared decision-making to consider deprescribing if warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the volunteers from the Michigan Medicine Office of Patient Experience for their contribution to the development of this survey.

J.K.S. is supported by the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award. This work was additionally supported by the University Internal Medicine Faculty Quality Improvement Award and by the 2022 Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society Mentored Research Award, which was supported by an educational grant from Takeda (all J.K.S.). J.E.K. is supported by a K23 Award from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK118179) and Department of Veterans Affairs grant QUE 20-025.

Authorship

Contribution: E.S. and J.K.S. conceived and designed the initial survey; E.S., J.K.S., L.B., and R.P. helped administer the survey; C.P., J.K.S., and N.C. analyzed the data; N.C. and J.K.S. prepared the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors contributed to the survey design, were involved in the revision of the draft manuscript, and agreed to the final content.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.K.S. reports consulting for Pfizer and Sanofi. G.D.B. reports being on the Board of Directors for Anticoagulation Forum; participating on a data safety monitoring board for Translational Sciences; and consulting for Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Bayer, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Anthos, Abbott Vascular, and Boston Scientific. J.E.K. reports honoraria from the Anticoagulation Forum and being on the American Gastroenterological Association Quality Committee. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jordan K. Schaefer, University of Michigan, C366 Med Inn Building, 1500 E. Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109; email: jschaef@med.umich.edu.

References

Author notes

Primary data are unable to be shared due to privacy restrictions. Deidentified data may be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Jordan K. Schaefer (jschaef@med.umich.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.