Key Points

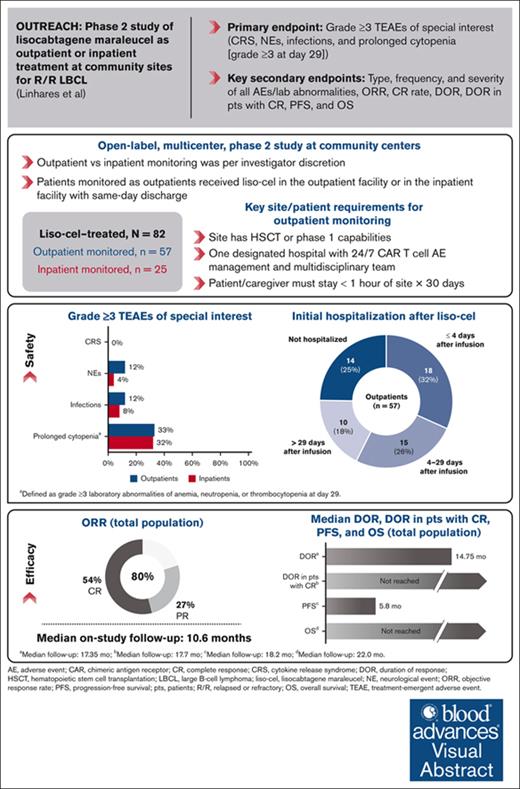

Liso-cel treatment at community sites with outpatient or inpatient monitoring demonstrated high, durable responses and manageable safety.

Liso-cel treatment in the community setting with outpatient monitoring is feasible in appropriate patients using standard procedures.

Visual Abstract

Lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) is an autologous, CD19-directed, 4-1BB chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell product approved for relapsed/refractory (R/R) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL). We present the OUTREACH primary analysis, evaluating the safety and efficacy of outpatient monitoring after liso-cel treatment at community sites in the United States. Adults with R/R LBCL after ≥2 prior lines of therapy received liso-cel. Outpatient vs inpatient monitoring was per investigator discretion. The primary end points were incidences of grade ≥3 cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurological events (NEs), prolonged cytopenia, and infections. Efficacy was a secondary end point. Eighty-two patients received liso-cel (outpatient monitored, 70%; inpatient monitored, 30%). The median follow-up was 10.6 months (range, 1.0-24.5). In outpatients and inpatients, grade ≥3 CRS occurred in 0% and 0%, NEs in 12% and 4%, infections in 12% and 8%, and prolonged cytopenia in 33% and 32%, respectively. Among outpatients, 25% were never hospitalized after infusion, and 32% were hospitalized ≤72 hours after the day of infusion; the median time to hospitalization was 5.0 days (range, 2-310). The median initial hospitalization duration after liso-cel was 6.0 days (range, 1-28) for outpatients and 15.0 days (range, 3-31) for inpatients. Objective response rate was 80%, complete response rate was 54%, and the median duration of response was 14.75 months (95% confidence interval, 5.0 to not reached). OUTREACH is, to our knowledge, the first and largest study to prospectively assess CAR T-cell therapy with outpatient monitoring in community-based medical centers. Liso-cel demonstrated meaningful efficacy with favorable safety in patients with R/R LBCL. Data support the feasibility of liso-cel administration at community sites with outpatient monitoring. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT03744676.

Introduction

In the United States, ∼70% of patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) receive treatment at community medical centers, where outpatient delivery of cancer therapy has become common.1 Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies have traditionally been administered as inpatient treatment at university medical centers owing to concerns of adverse event (AE) management, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurological events (NEs).2,3 However, there is increasing interest in administering CAR T-cell therapies at community medical centers and as outpatient therapy to increase accessibility and reduce costs.4,5 CAR T-cell therapies using 4-1BB costimulatory domains have been associated with fewer CRS (42%-58%) and severe NEs (10%-12%) than those using CD28 costimulatory domains (CRS, 93%; severe NEs, 28%),6-8 suggesting they may be better candidates for outpatient treatment in appropriate patients at the discretion of treating physicians. Lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) is an autologous, CD19-directed, 4-1BB CAR T-cell product.8 Liso-cel has demonstrated meaningful efficacy, with an objective response rate (ORR) of 73% and a complete response (CR) rate of 53% as third-line or later treatment for patients with R/R LBCL in the TRANSCEND NHL 001 (TRANSCEND; NCT02631044) study. Incidences of grade 3 or 4 CRS (2%) and NEs (10%) were low, and no grade 5 events occurred,8 supporting outpatient administration and monitoring for toxicity. Based on the observed favorable benefit/risk profile of liso-cel, outpatient administration and subsequent monitoring were successfully implemented in multiple clinical trials, including TRANSCEND, PILOT, and TRANSFORM, at academic medical centers using carefully developed standard operating procedures.8-10 OUTREACH (NCT03744676) is a safety study modeled on the TRANSCEND study and was specifically designed to evaluate liso-cel as third-line or later treatment in patients with R/R LBCL at community medical centers in the United States across outpatient and inpatient settings. Here, we present the primary analysis results from the study.

Methods

Study design and participants

OUTREACH is an open-label, multicenter, phase 2 study conducted at community centers in the United States, defined as nontertiary care centers not associated with a university, including sites with and without Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy (FACT) accreditation; with outpatient infusion centers (single entity) or oncology clinics with separate associated hospitals (dual entity); and with or without prior experience administering CAR T-cell therapy. Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of <2 and positron emission tomography (PET)–positive R/R LBCL per Lugano 2014 criteria.11 Patients had R/R disease after receiving ≥2 previous lines of systemic treatment. Full eligibility criteria and study conduct description are provided in the supplemental Appendix.

All patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. The study protocol and amendments were approved by institutional review boards at each participating site.

Procedures

Enrolled patients underwent leukapheresis to obtain peripheral blood mononuclear cells for liso-cel manufacturing. Bridging therapy after leukapheresis was allowed for disease control per treating investigator during the liso-cel manufacturing process, but ≥7 days of washout and reconfirmation of PET-positive disease were required before lymphodepleting chemotherapy (LDC). Patients received LDC (fludarabine 30 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 daily for 3 days) followed by liso-cel infusion 2 to 7 days later at a dose of 100 × 106 CAR+ T cells. Retreatment with liso-cel was not permitted per protocol.

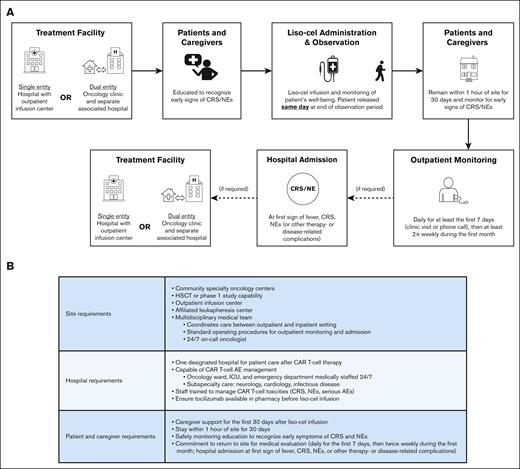

Liso-cel infusion and monitoring were to be delivered in the outpatient setting; inpatient treatment and monitoring after liso-cel infusion was allowed at the treating investigator’s discretion. Patients were considered to be monitored as outpatients if liso-cel was administered in the outpatient facility or in the inpatient facility with subsequent discharge the same day at the end of the observation period (Figure 1A). For outpatient monitoring, community centers were required to have hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or phase 1 study capabilities and a multidisciplinary medical team with standard operating procedures for outpatient monitoring and admission. Patients were required to both have a caregiver and remain within 1 hour of the site for 30 days after liso-cel infusion. One designated hospital capable of providing oncology care with tocilizumab available in pharmacy before liso-cel infusion and 24/7 CAR T-cell AE management was required. Standard operating procedures, including full outpatient monitoring requirements and study site characteristics, are provided in the supplemental Appendix and Figure 1B.

Outpatient requirements in OUTREACH. (A) Outpatient CAR T-cell treatment. Patients were considered to be monitored as outpatients if liso-cel was administered in the outpatient facility or in the inpatient facility with subsequent discharge the same day at the end of the observation period. (B) Site and patient requirements.

Outpatient requirements in OUTREACH. (A) Outpatient CAR T-cell treatment. Patients were considered to be monitored as outpatients if liso-cel was administered in the outpatient facility or in the inpatient facility with subsequent discharge the same day at the end of the observation period. (B) Site and patient requirements.

End points and assessments

The primary end point was the incidence of grade ≥3 AEs of special interest (AESIs) of CRS, NEs, infections, and prolonged cytopenias (defined as grade ≥3 laboratory abnormalities of anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia at day 29). Secondary safety end points were the type, frequency, and severity of all AEs and laboratory abnormalities in outpatients and in the total population. Grading of AEs is described in the supplemental Appendix. The treatment-emergent period was defined as the time from initiation of liso-cel administration up to and including 90 days after liso-cel infusion. Any AEs occurring after the initiation of another anticancer therapy were not considered treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs).

Secondary efficacy end points included ORR (CR plus partial response [PR]) and CR rate per investigator, duration of response (DOR), DOR in patients with CR, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). End point definitions are provided in the supplemental Appendix. Tumor response assessments were evaluated per investigator by PET/computed tomography according to the Lugano 2014 criteria.11 Radiographic disease assessments were to be performed before treatment, on day 29, and at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months after liso-cel infusion or until disease progression.

Additional secondary end points included cellular kinetic parameters of liso-cel in blood as measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction12 and health-related quality of life/patient-reported outcomes and health economics outcomes research.13 Exploratory end points included CD19+ B-cell aplasia (<3% CD19+ B cells in peripheral blood lymphocytes) using flow cytometry.

Safety and efficacy analyses were conducted in all patients who received liso-cel infusion (liso-cel–treated set). The primary end point was descriptive. No formal testing between outpatient and inpatient monitoring groups was performed. Additional statistical methods are described in the legend of Figure 3 and the supplemental Appendix.

Results

Patients

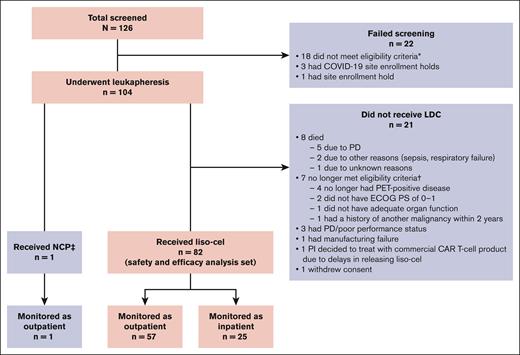

Between 29 November 2018 and 7 December 2021, a total of 104 patients underwent leukapheresis, and 82 received liso-cel (liso-cel–treated set or total population). One patient received nonconforming CAR T-cell product, defined as any CAR T-cell product wherein one of the CD8 or CD4 cell components did not meet 1 of the requirements to be considered liso-cel but could be considered appropriate for infusion; for this patient, the CD8 component was out of specifications. The most common reasons for not proceeding with liso-cel infusion after leukapheresis were death or no longer meeting eligibility criteria (Figure 2). Of the 18 sites that enrolled patients, 44% were without FACT accreditation (non-FACT), 56% were dual entity (oncology clinics with separate associated hospitals), and 72% had not previously treated patients with CAR T-cell therapy (supplemental Table 1). Of 82 total patients treated with liso-cel, 37% were treated at non-FACT sites, 48% were treated at dual-entity sites, and 32% were treated at CAR T-cell–naïve sites.

CONSORT diagram (intention-to-treat set). ∗Screen failures due to not meeting eligibility criteria included not having an eligible R/R LBCL histology (n = 6), social/familial/geographical conditions (n = 5), not having PET-positive disease (n = 3), not signing the informed consent form before study procedures (n = 1), not having adequate cardiac function (n = 1), history of cardiovascular condition (n = 1), and receipt of radiation within 6 weeks of leukapheresis (n = 1). †One patient did not meet 2 eligibility criteria (ECOG PS of 0-1 and inadequate renal function). ‡NCP was defined as any CAR T-cell product wherein one of the CD8 or CD4 cell components did not meet 1 of the requirements to be considered liso-cel but could be considered appropriate for infusion. The patient who received NCP (CD8 component was out of specifications) was not included in the safety/efficacy analysis. ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; NCP, nonconforming product; PD, progressive disease; PI, principal investigator.

CONSORT diagram (intention-to-treat set). ∗Screen failures due to not meeting eligibility criteria included not having an eligible R/R LBCL histology (n = 6), social/familial/geographical conditions (n = 5), not having PET-positive disease (n = 3), not signing the informed consent form before study procedures (n = 1), not having adequate cardiac function (n = 1), history of cardiovascular condition (n = 1), and receipt of radiation within 6 weeks of leukapheresis (n = 1). †One patient did not meet 2 eligibility criteria (ECOG PS of 0-1 and inadequate renal function). ‡NCP was defined as any CAR T-cell product wherein one of the CD8 or CD4 cell components did not meet 1 of the requirements to be considered liso-cel but could be considered appropriate for infusion. The patient who received NCP (CD8 component was out of specifications) was not included in the safety/efficacy analysis. ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; NCP, nonconforming product; PD, progressive disease; PI, principal investigator.

After liso-cel infusion, 57 patients were monitored in the outpatient setting, and 25 patients were monitored in the inpatient setting at their treating investigator’s discretion. Reasons for inpatient monitoring were disease characteristics (48%), including tumor burden and risk of AEs; psychosocial factors (32%), including lack of caregiver support or transportation; COVID-19 precautions (8%); preinfusion AEs (8%) of fever and vasovagal reaction; and principal investigator decision (4%) due to limited hospital experience with CAR T-cell therapy (supplemental Table 2).

In the total population, 54% of patients were aged ≥65 years, 91% were refractory to last prior therapy, and 49% had high disease burden characteristics (lactate dehydrogenase ≥500 units per L [28%] and/or sum of the product of perpendicular diameters ≥50 cm2 [38%]; Table 1). Approximately half of all patients (54%) received bridging therapy. The most frequently used bridging therapies are shown in supplemental Table 3. Baseline patient and disease characteristics were generally similar for outpatients vs inpatients, except for the proportions of patients with diffuse LBCL transformed from indolent histologies (26% vs 4%), high-grade B-cell lymphoma (7% vs 44%), sum of the product of perpendicular diameters ≥50 cm2 (31% vs 54%), and who received bridging therapy (44% vs 76%, respectively). At data cutoff (17 June 2022), the median follow-up from the time of liso-cel infusion was 10.6 months (range, 1.0-24.5) in the total population.

Demographics and baseline disease characteristics (liso-cel–treated set)

| . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . | Total (N = 82) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), y | 65 (28-83) | 69 (34-86) | 66 (28-86) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 29 (51) | 15 (60) | 44 (54) |

| ≥75, n (%) | 11 (19) | 5 (20) | 16 (20) |

| Male, n (%) | 39 (68) | 15 (60) | 54 (66) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 49 (86) | 20 (80) | 69 (84) |

| Other | 4 (7) | 3 (12) | 7 (9) |

| Unknown | 4 (7) | 2 (8) | 6 (7) |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| DLBCL NOS | 37 (65) | 13 (52) | 50 (61) |

| tDLBCL from indolent histologies | 15 (26)∗ | 1 (4)† | 16 (20) |

| HGBCL‡ | 4 (7) | 11 (44) | 15 (18) |

| Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Secondary CNS lymphoma, n (%) | 0 | 2 (8) | 2 (2) |

| ECOG PS at screening, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 19 (33) | 8 (32) | 27 (33) |

| 1 | 38 (67) | 17 (68) | 55 (67) |

| Ann Arbor disease, n (%) | |||

| Stage I | 6 (11) | 0 | 6 (7) |

| Stage II | 10 (18) | 5 (20) | 15 (18) |

| Stage III | 18 (32) | 5 (20) | 23 (28) |

| Stage IV | 23 (40) | 15 (60) | 38 (46) |

| Median no. of prior lines of therapy (range) | 2 (2-4) | 2 (2-6) | 2 (2-6) |

| Received prior HSCT, n (%) | 11 (19) | 2 (8) | 13 (16) |

| Refractory to last prior therapy, n (%)§ | 51 (89) | 24 (96) | 75 (91) |

| Chemotherapy refractory,|| n (%) | 47 (82) | 21 (84) | 68 (83) |

| LDH ≥500 units per L,¶ n (%) | 15 (26) | 8 (32) | 23 (28) |

| SPD ≥50 cm2,¶ n (%) | 17 (31) | 13 (54) | 30 (38) |

| CRP ≥20 mg/L,¶ n (%) | 28 (49) | 16 (64) | 44 (54) |

| Received bridging therapy,# n (%) | 25 (44) | 19 (76) | 44 (54) |

| . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . | Total (N = 82) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), y | 65 (28-83) | 69 (34-86) | 66 (28-86) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 29 (51) | 15 (60) | 44 (54) |

| ≥75, n (%) | 11 (19) | 5 (20) | 16 (20) |

| Male, n (%) | 39 (68) | 15 (60) | 54 (66) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 49 (86) | 20 (80) | 69 (84) |

| Other | 4 (7) | 3 (12) | 7 (9) |

| Unknown | 4 (7) | 2 (8) | 6 (7) |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| DLBCL NOS | 37 (65) | 13 (52) | 50 (61) |

| tDLBCL from indolent histologies | 15 (26)∗ | 1 (4)† | 16 (20) |

| HGBCL‡ | 4 (7) | 11 (44) | 15 (18) |

| Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Secondary CNS lymphoma, n (%) | 0 | 2 (8) | 2 (2) |

| ECOG PS at screening, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 19 (33) | 8 (32) | 27 (33) |

| 1 | 38 (67) | 17 (68) | 55 (67) |

| Ann Arbor disease, n (%) | |||

| Stage I | 6 (11) | 0 | 6 (7) |

| Stage II | 10 (18) | 5 (20) | 15 (18) |

| Stage III | 18 (32) | 5 (20) | 23 (28) |

| Stage IV | 23 (40) | 15 (60) | 38 (46) |

| Median no. of prior lines of therapy (range) | 2 (2-4) | 2 (2-6) | 2 (2-6) |

| Received prior HSCT, n (%) | 11 (19) | 2 (8) | 13 (16) |

| Refractory to last prior therapy, n (%)§ | 51 (89) | 24 (96) | 75 (91) |

| Chemotherapy refractory,|| n (%) | 47 (82) | 21 (84) | 68 (83) |

| LDH ≥500 units per L,¶ n (%) | 15 (26) | 8 (32) | 23 (28) |

| SPD ≥50 cm2,¶ n (%) | 17 (31) | 13 (54) | 30 (38) |

| CRP ≥20 mg/L,¶ n (%) | 28 (49) | 16 (64) | 44 (54) |

| Received bridging therapy,# n (%) | 25 (44) | 19 (76) | 44 (54) |

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CNS, central nervous system; CRP, C-reactive protein; DLBCL, diffuse LBCL; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; FL, follicular lymphoma; HGBCL, high-grade B-cell lymphoma; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NOS, not otherwise specified; PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; SPD, sum of the product of perpendicular diameters; tDLBCL, transformed diffuse LBCL.

Transformed from FL (n = 14) and Waldenström macroglobulinemia (n = 1).

Transformed from CLL/SLL (n = 1).

Includes high-grade lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements with DLBCL histology.

Best response of PR, SD, or PD to last systemic or transplant treatment with curative intent.

Defined as experiencing SD or PD to the last treatment with curative intent (ie, systemic or transplant) that patients received before coming on this study or relapsed <12 months after autologous HSCT; patients who were not chemotherapy refractory were considered to be chemotherapy sensitive.

Percentages are based on number of patients with nonmissing results.

Types of bridging therapy included systemic treatment only (n = 23), radiotherapy only (n = 1), or both systemic treatment and radiotherapy (n = 1) in the outpatient group and systemic treatment only (n = 19) in the inpatient group.

Safety

The most common any-grade TEAEs in the total population were neutropenia, leukopenia, CRS, thrombocytopenia, and anemia (Table 2). The incidence of grade ≥3 TEAEs was generally similar between outpatients and inpatients (74% vs 76%, respectively); the most common grade ≥3 TEAEs were cytopenias. No grade 5 TEAEs were reported.

TEAEs (liso-cel–treated set)

| n (%) . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . | Total (N = 82) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade ≥3 . | Any grade . | Grade ≥3 . | Any grade . | Grade ≥3 . | |

| Any TEAE | 57 (100) | 42 (74) | 25 (100) | 19 (76) | 82 (100) | 61 (74) |

| Any SAE | 33 (58) | — | 15 (60) | — | 48 (59) | — |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥10% of patients | ||||||

| Neutropenia | 37 (65) | 31 (54) | 18 (72) | 18 (72) | 55 (67) | 49 (60) |

| Leukopenia | 24 (42) | 22 (39) | 12 (48) | 11 (44) | 36 (44) | 33 (40) |

| CRS | 21 (37) | 0 | 12 (48) | 0 | 33 (40) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 20 (35) | 14 (25) | 9 (36) | 5 (20) | 29 (35) | 19 (23) |

| Anemia | 17 (30) | 13 (23) | 10 (40) | 8 (32) | 27 (33) | 21 (26) |

| Fatigue | 20 (35) | 2 (4) | 5 (20) | 0 | 25 (30) | 2 (2) |

| Headache | 15 (26) | 0 | 8 (32) | 0 | 23 (28) | 0 |

| Nausea | 12 (21) | 0 | 9 (36) | 0 | 21 (26) | 0 |

| Constipation | 15 (26) | 0 | 4 (16) | 0 | 19 (24) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 14 (25) | 4 (7) | 5 (20) | 0 | 19 (24) | 4 (5) |

| Diarrhea | 14 (25) | 2 (4) | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 19 (24) | 3 (4) |

| Lymphopenia | 11 (19) | 10 (18) | 6 (24) | 5 (20) | 17 (21) | 15 (18) |

| Arthralgia | 12 (21) | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 15 (18) | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 8 (14) | 0 | 7 (28) | 0 | 15 (18) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 8 (14) | 0 | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 13 (16) | 1 (1) |

| Back pain | 8 (14) | 0 | 4 (16) | 0 | 12 (15) | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 8 (14) | 2 (4) | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 11 (13) | 3 (4) |

| Tremor | 8 (14) | 2 (4) | 3 (12) | 0 | 11 (13) | 2 (2) |

| Hypotension | 9 (16) | 5 (9) | 1 (4) | 0 | 10 (12) | 5 (6) |

| Peripheral edema | 8 (14) | 1 (2) | 2 (8) | 0 | 10 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 7 (12) | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 10 (12) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 7 (12) | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 9 (11) | 0 |

| Cough | 5 (9) | 0 | 4 (16) | 0 | 9 (11) | 0 |

| Pruritus | 6 (11) | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 9 (11) | 0 |

| n (%) . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . | Total (N = 82) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade . | Grade ≥3 . | Any grade . | Grade ≥3 . | Any grade . | Grade ≥3 . | |

| Any TEAE | 57 (100) | 42 (74) | 25 (100) | 19 (76) | 82 (100) | 61 (74) |

| Any SAE | 33 (58) | — | 15 (60) | — | 48 (59) | — |

| TEAEs occurring in ≥10% of patients | ||||||

| Neutropenia | 37 (65) | 31 (54) | 18 (72) | 18 (72) | 55 (67) | 49 (60) |

| Leukopenia | 24 (42) | 22 (39) | 12 (48) | 11 (44) | 36 (44) | 33 (40) |

| CRS | 21 (37) | 0 | 12 (48) | 0 | 33 (40) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 20 (35) | 14 (25) | 9 (36) | 5 (20) | 29 (35) | 19 (23) |

| Anemia | 17 (30) | 13 (23) | 10 (40) | 8 (32) | 27 (33) | 21 (26) |

| Fatigue | 20 (35) | 2 (4) | 5 (20) | 0 | 25 (30) | 2 (2) |

| Headache | 15 (26) | 0 | 8 (32) | 0 | 23 (28) | 0 |

| Nausea | 12 (21) | 0 | 9 (36) | 0 | 21 (26) | 0 |

| Constipation | 15 (26) | 0 | 4 (16) | 0 | 19 (24) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 14 (25) | 4 (7) | 5 (20) | 0 | 19 (24) | 4 (5) |

| Diarrhea | 14 (25) | 2 (4) | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 19 (24) | 3 (4) |

| Lymphopenia | 11 (19) | 10 (18) | 6 (24) | 5 (20) | 17 (21) | 15 (18) |

| Arthralgia | 12 (21) | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 15 (18) | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 8 (14) | 0 | 7 (28) | 0 | 15 (18) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 8 (14) | 0 | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 13 (16) | 1 (1) |

| Back pain | 8 (14) | 0 | 4 (16) | 0 | 12 (15) | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 8 (14) | 2 (4) | 3 (12) | 1 (4) | 11 (13) | 3 (4) |

| Tremor | 8 (14) | 2 (4) | 3 (12) | 0 | 11 (13) | 2 (2) |

| Hypotension | 9 (16) | 5 (9) | 1 (4) | 0 | 10 (12) | 5 (6) |

| Peripheral edema | 8 (14) | 1 (2) | 2 (8) | 0 | 10 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 7 (12) | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 10 (12) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 7 (12) | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 9 (11) | 0 |

| Cough | 5 (9) | 0 | 4 (16) | 0 | 9 (11) | 0 |

| Pruritus | 6 (11) | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 9 (11) | 0 |

—, not available or not reported; SAE, serious AE.

Treatment-emergent AESIs are described in Table 3. In the total population, 40 patients (49%) developed any-grade CRS, NEs, or both. All events of CRS were grade 1 or 2; no grade 3 to 5 CRS was reported. Grade 3 to 4 NEs occurred in 8 patients (10%; grade 3, n = 6 [7%]; grade 4, n = 2 [2%]), and all resolved or were resolving at data cutoff; no grade 5 events occurred. Rates of any-grade CRS were slightly lower in outpatients vs inpatients (37% vs 48%, respectively), and rates of any-grade NEs were similar (28% vs 32%, respectively; grade ≥3, 12% vs 4%). Time to onset and resolution of CRS and NEs were generally similar between monitoring groups. CRS and/or NEs were managed by treatment with tocilizumab, corticosteroids, or both in 24 patients (29%; outpatients, 26%; inpatients, 36%). No prophylactic corticosteroids were used. Prolonged cytopenias (grade ≥3 laboratory values at day 29) were reported in 27 patients (33%), with recovery to grade ≤2 in most patients by day 90 (Table 3). Grade ≥3 infections occurred in 9 patients (11%; outpatients, 12%; inpatients, 8%). In the 7 outpatients, the events were COVID-19 infection, Clostridium difficile infection, urinary tract infection, bacteremia, and sepsis in 1 patient each; 2 patients had concurrent AEs (pneumonia and sepsis, n = 1; sepsis, urosepsis, and fungal skin infection, n = 1). In the 2 inpatients, sepsis and C difficile colitis occurred in 1 patient each. No grade 5 infections occurred.

Treatment-emergent AESI and hospitalization (liso-cel–treated set)

| AESI . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . | Total (N = 82) . |

| CRS or NEs, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 26 (46) | 14 (56) | 40 (49) |

| Grade ≥3 | 7 (12) | 1 (4) | 8 (10) |

| CRS, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 21 (37) | 12 (48) | 33 (40) |

| Grade 1 | 15 (26) | 8 (32) | 23 (28) |

| Grade 2 | 6 (11) | 4 (16) | 10 (12) |

| Grade ≥3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median time to onset of any-grade CRS (range), d | 4.0 (1-9) | 3.0 (1-9) | 4.0 (1-9) |

| Median time to onset of grade ≥3 CRS (range), d | NA | NA | NA |

| Median time to resolution of any-grade CRS (range), d | 5.0 (1-15) | 4.5 (1-15) | 5.0 (1-15) |

| Median time to resolution of grade ≥3 CRS (range), d | NA | NA | NA |

| NEs, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 16 (28) | 8 (32) | 24 (29) |

| Grade 1 | 5 (9) | 2 (8) | 7 (9) |

| Grade 2 | 4 (7) | 5 (20) | 9 (11) |

| Grade 3 | 5 (9) | 1 (4) | 6 (7) |

| Grade 4 | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Grade 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median time to onset of any-grade NEs (range), d | 8.0 (3-33) | 7.0 (3-16) | 7.5 (3-33) |

| Median time to onset of grade ≥3 NEs (range), d | 10.0 (8-33) | 3.0 (3-3) | 9.5 (3-33) |

| Median time to resolution of any-grade NEs (range), d | 9.0 (1-47) | 9.5 (3-35) | 9.0 (1-47) |

| Median time to resolution of grade ≥3 NEs (range), d | 21.0 (7-47) | 5.0 (5-5) | 16.5 (5-47) |

| Treatment with tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids for CRS or NEs, n (%) | 15 (26) | 9 (36) | 24 (29) |

| Tocilizumab only | 1 (2) | 3 (12) | 4 (5) |

| Corticosteroids only | 4 (7) | 6 (24) | 10 (12) |

| Both tocilizumab and corticosteroid | 10 (18) | 0 | 10 (12) |

| Infections,∗n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 19 (33) | 8 (32) | 27 (33) |

| Grade ≥3† | 7 (12) | 2 (8) | 9 (11) |

| Grade ≥3 prolonged cytopenias at day 29,‡n (%) | 19 (33) | 8 (32) | 27 (33) |

| Grade ≥3 decreased hemoglobin at day 29, n (%) | 6 (11) | 3 (12) | 9 (11) |

| Median time to recovery to grade ≤2 in 8 patients (range),§ d | 5.5 (3-22) | 22.0 (15-29) | 9.0 (3-29) |

| Grade ≥3 decreased platelets at day 29, n (%) | 15 (26) | 5 (20) | 20 (24) |

| Median time to recovery to grade ≤2 in 12 patients (range),|| d | 20.5 (5-39) | 29.0 (8-136) | 22.0 (5-136) |

| Grade ≥3 decreased neutrophils at day 29, n (%) | 9 (16) | 6 (24) | 15 (18) |

| Median time to recovery to grade ≤2 in 13 patients (range),¶ d | 12.5 (4-33) | 8.0 (8-32) | 10.0 (4-33) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 8 (14) | 3 (12) | 11 (13) |

| Grade ≥3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SPM, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Grade ≥3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AESI . | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . | Total (N = 82) . |

| CRS or NEs, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 26 (46) | 14 (56) | 40 (49) |

| Grade ≥3 | 7 (12) | 1 (4) | 8 (10) |

| CRS, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 21 (37) | 12 (48) | 33 (40) |

| Grade 1 | 15 (26) | 8 (32) | 23 (28) |

| Grade 2 | 6 (11) | 4 (16) | 10 (12) |

| Grade ≥3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median time to onset of any-grade CRS (range), d | 4.0 (1-9) | 3.0 (1-9) | 4.0 (1-9) |

| Median time to onset of grade ≥3 CRS (range), d | NA | NA | NA |

| Median time to resolution of any-grade CRS (range), d | 5.0 (1-15) | 4.5 (1-15) | 5.0 (1-15) |

| Median time to resolution of grade ≥3 CRS (range), d | NA | NA | NA |

| NEs, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 16 (28) | 8 (32) | 24 (29) |

| Grade 1 | 5 (9) | 2 (8) | 7 (9) |

| Grade 2 | 4 (7) | 5 (20) | 9 (11) |

| Grade 3 | 5 (9) | 1 (4) | 6 (7) |

| Grade 4 | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Grade 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median time to onset of any-grade NEs (range), d | 8.0 (3-33) | 7.0 (3-16) | 7.5 (3-33) |

| Median time to onset of grade ≥3 NEs (range), d | 10.0 (8-33) | 3.0 (3-3) | 9.5 (3-33) |

| Median time to resolution of any-grade NEs (range), d | 9.0 (1-47) | 9.5 (3-35) | 9.0 (1-47) |

| Median time to resolution of grade ≥3 NEs (range), d | 21.0 (7-47) | 5.0 (5-5) | 16.5 (5-47) |

| Treatment with tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids for CRS or NEs, n (%) | 15 (26) | 9 (36) | 24 (29) |

| Tocilizumab only | 1 (2) | 3 (12) | 4 (5) |

| Corticosteroids only | 4 (7) | 6 (24) | 10 (12) |

| Both tocilizumab and corticosteroid | 10 (18) | 0 | 10 (12) |

| Infections,∗n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 19 (33) | 8 (32) | 27 (33) |

| Grade ≥3† | 7 (12) | 2 (8) | 9 (11) |

| Grade ≥3 prolonged cytopenias at day 29,‡n (%) | 19 (33) | 8 (32) | 27 (33) |

| Grade ≥3 decreased hemoglobin at day 29, n (%) | 6 (11) | 3 (12) | 9 (11) |

| Median time to recovery to grade ≤2 in 8 patients (range),§ d | 5.5 (3-22) | 22.0 (15-29) | 9.0 (3-29) |

| Grade ≥3 decreased platelets at day 29, n (%) | 15 (26) | 5 (20) | 20 (24) |

| Median time to recovery to grade ≤2 in 12 patients (range),|| d | 20.5 (5-39) | 29.0 (8-136) | 22.0 (5-136) |

| Grade ≥3 decreased neutrophils at day 29, n (%) | 9 (16) | 6 (24) | 15 (18) |

| Median time to recovery to grade ≤2 in 13 patients (range),¶ d | 12.5 (4-33) | 8.0 (8-32) | 10.0 (4-33) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 8 (14) | 3 (12) | 11 (13) |

| Grade ≥3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SPM, n (%) | |||

| Any grade | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Grade ≥3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hospitalizations . | ||

|---|---|---|

| . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . |

| Patients hospitalized, n (%) | 43 (75) | 25 (100) |

| Median time to initial hospitalization in outpatients (range), d | 5.0 (2-310) | NA# |

| Time to initial hospitalization in outpatients, n (%) | ||

| Within 72 h after day of infusion | 18 (32) | NA |

| 72 h to 29 d after day of infusion | 15 (26) | NA |

| >29 d after day of infusion | 10 (18) | NA |

| Not hospitalized | 14 (25) | NA |

| Median duration of initial hospitalization (range), d | ||

| All hospitalized patients | 6.0 (1-28) | 15.0 (3-31) |

| Patients hospitalized within 72 h after day of infusion | 9.5 (4-28) | NA |

| ICU stays during initial hospitalization | ||

| Patients admitted to the ICU, n (%) | 1 (2) | 2 (8) |

| Median duration of ICU admission (range), d∗∗ | 5.0 (5-5) | 5.5 (4-7) |

| Hospitalizations . | ||

|---|---|---|

| . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . |

| Patients hospitalized, n (%) | 43 (75) | 25 (100) |

| Median time to initial hospitalization in outpatients (range), d | 5.0 (2-310) | NA# |

| Time to initial hospitalization in outpatients, n (%) | ||

| Within 72 h after day of infusion | 18 (32) | NA |

| 72 h to 29 d after day of infusion | 15 (26) | NA |

| >29 d after day of infusion | 10 (18) | NA |

| Not hospitalized | 14 (25) | NA |

| Median duration of initial hospitalization (range), d | ||

| All hospitalized patients | 6.0 (1-28) | 15.0 (3-31) |

| Patients hospitalized within 72 h after day of infusion | 9.5 (4-28) | NA |

| ICU stays during initial hospitalization | ||

| Patients admitted to the ICU, n (%) | 1 (2) | 2 (8) |

| Median duration of ICU admission (range), d∗∗ | 5.0 (5-5) | 5.5 (4-7) |

NA, not applicable; SPM, second primary malignancy.

Includes all TEAEs from the infections and infestations System Organ Class.

Grade ≥3 infections among outpatients included sepsis (n = 3) and bacteremia, COVID-19, C difficile infection, fungal skin infection, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and urosepsis (n = 1 each); among inpatients, sepsis and C difficile colitis (n = 1 each).

Any grade ≥3 laboratory results of anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia at day 29 after liso-cel infusion.

Recovery data are presented for the 6 outpatients and 2 inpatients who had hemoglobin laboratory results after day 29.

Recovery data are presented for the 10 outpatients and 2 inpatients who had platelet laboratory results after day 29.

Recovery data are presented for the 8 outpatients and 5 inpatients who had neutrophil laboratory results after day 29.

Time to initial hospitalization was NA in inpatients, because all inpatients were already hospitalized for monitoring.

For inpatients, calculated as date of discharge minus first liso-cel dose date plus 1. For outpatients, calculated as date of discharge minus date of admission after liso-cel administration plus 1.

Among other treatment-emergent AESIs, any-grade hypogammaglobulinemia was reported in 11 patients (13%) in the total population, with no grade ≥3 events reported. A total of 6 patients (7%) experienced a second primary malignancy while on study; of these, 1 occurred during the treatment-emergent period (squamous cell carcinoma of the skin that was removed by an excisional biopsy). No macrophage activation syndrome, tumor lysis syndrome, or infusion-related reactions were reported.

Of the 33 deaths after liso-cel infusion, most patients died because of disease progression (n = 25; supplemental Table 4). Five deaths were due to AEs. There was no grade 5 TEAE; however, 1 patient died within the 90-day period after liso-cel infusion. The patient experienced disease progression with extensive masses in the colon, abdomen, and pelvis leading to colonic perforation; withdrew from the study to transition to hospice care; and subsequently died on day 60 because of sepsis (starting on day 43). After the 90-day period, the 4 remaining deaths due to AEs were primary cytomegalovirus infection (related to liso-cel and unrelated to LDC per investigator), sepsis (related to liso-cel and LDC per investigator), second primary malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia (unrelated to liso-cel and related to LDC per investigator), and COVID-19 (unrelated to liso-cel or LDC per investigator).

Of 57 outpatients, 14 (25%) were never hospitalized after liso-cel infusion (Table 3). Initial hospitalization in 25 patients (44%) occurred >72 hours after the day of liso-cel infusion, including 10 (18%) who were admitted >29 days after infusion. The median time to initial hospitalization among all outpatients was 5.0 days (range, 2-310), with a duration of 6.0 days (range, 1-28); the most common reason for initial hospitalization was AEs (n = 35 [61%]), including CRS (n = 18), CRS and NE (n = 1), and febrile neutropenia (n = 5; supplemental Table 5). Of 18 outpatients (32%) admitted ≤72 hours after the day of liso-cel infusion, 16 were hospitalized because of AEs (CRS, n = 12; dehydration, n = 1; encephalopathy, n = 1; febrile neutropenia, n = 1; neutropenic fever, n = 1), 1 due to issues with caregiver support, and 1 for planned admission for observation; the median duration of stay was 9.5 days (range, 4-28).

All inpatients were hospitalized for liso-cel infusion and subsequent monitoring, including 19 (76%) admitted for prophylaxis for CAR T-cell administration (eg, to monitor closely for infusion reactions, tumor lysis syndrome, CRS/NEs, or infection) and 6 (24%) admitted before liso-cel administration for AEs (n = 2) or other reasons (n = 4) who remained hospitalized for infusion and monitoring (supplemental Table 6). The median duration of initial hospitalization was 15.0 days (range, 3-31) among all inpatients.

One outpatient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) during their initial hospitalization for an AE of encephalopathy. Two inpatients were admitted to the ICU during their initial hospitalization (1 for COVID-19 precaution and the other for closer monitoring after developing grade 1 CRS followed by grade 1 encephalopathy in the setting of high baseline tumor burden; Table 3). The duration of ICU admission was 5.0 days for the 1 outpatient and a median of 5.5 days (range, 4-7) for the 2 inpatients. The median duration of all hospitalizations during study follow-up, including patients who had multiple hospitalization stays, was 7.0 days (range, 0-67) among outpatients and 16.0 days (range, 6-64) among inpatients.

Efficacy

Among all 82 liso-cel–treated patients, the ORR was 80% (n = 66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 70.3-88.4), and it was similar between outpatients (82% [95% CI, 70.1-91.3]) and inpatients (76% [95% CI, 54.9-90.6]; Table 4). The ORR in patient subgroups by demographic and baseline disease characteristics are shown in supplemental Figure 1. The ORR was generally consistent across subgroups containing ≥10 patients, with a trend toward a decrease in ORR in patients with lactate dehydrogenase ≥500 U/L before LDC (ORR, 65.2%). The CR rate for the total population was 54% (95% CI, 42.3-64.7). The median time to first CR or PR was 0.85 months (range, 0.6-5.9); time to first CR was 0.95 months (range, 0.6-12.1). Among the 36 patients with a first response of PR, 14 (39%) later achieved a best response of CR, including 8 outpatients and 6 inpatients.

Summary of efficacy end points (liso-cel–treated set)

| . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . | Total (N = 82) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall response,∗n (%) | |||

| CR | 33 (58) | 11 (44) | 44 (54) |

| PR | 14 (25) | 8 (32) | 22 (27) |

| SD | 3 (5) | 3 (12) | 6 (7) |

| PD | 7 (12) | 3 (12) | 10 (12) |

| ORR | |||

| CR + PR, n (%) | 47 (82) | 19 (76) | 66 (80) |

| 95% CI† | 70.1-91.3 | 54.9-90.6 | 70.3-88.4 |

| CR rate | |||

| CR, n (%) | 33 (58) | 11 (44) | 44 (54) |

| 95% CI† | 44.1-70.9 | 24.4-65.1 | 42.3-64.7 |

| Median DOR (95% CI),‡mo | 11.1 (3.9 to NR) | NR (2.1 to NR) | 14.75 (5.0 to NR) |

| Median follow-up (95% CI),§ mo | 17.7 (16.95-22.8) | 17.3 (7.75-23.3) | 17.35 (16.95-22.7) |

| 6-mo probability of continued response, % (95% CI)‡ | 54 (38.9-67.3) | 58 (33.2-76.3) | 55 (42.5-66.4) |

| 12-mo probability of continued response, % (95% CI)‡ | 50 (34.6-63.1) | 51 (26.0-70.9) | 50 (37.5-61.8) |

| Median DOR in patients achieving CR (95% CI),‡mo | NR (11.1 to NR) | NR (8.7 to NR) | NR (16.6 to NR) |

| Median follow-up (95% CI),§ mo | 17.4 (16.95-22.8) | 17.3 (7.7-23.5) | 17.7 (16.95-22.8) |

| 6-mo probability of continued response, % (95% CI)‡ | 75 (56.0-86.6) | 91 (50.8-98.7) | 79 (63.5-88.5) |

| 12-mo probability of continued response, % (95% CI)‡ | 68 (49.1-81.6) | 79.5 (39.3-94.5) | 71.5 (55.2-82.7) |

| Median PFS (95% CI),‡mo | 6.05 (2.9 to NR) | 4.3 (2.8 to NR) | 5.8 (3.0-15.6) |

| Median follow-up (95% CI),§ mo | 18.6 (17.8-23.7) | 18.0 (8.5-24.0) | 18.2 (17.8-23.7) |

| 6-mo probability of PFS, % (95% CI)‡ | 51 (37.3-62.9) | 44 (24.5-61.9) | 49 (37.6-59.0) |

| 12-mo probability of PFS, % (95% CI)‡ | 42 (28.6-54.0) | 38.5 (19.5-57.3) | 41 (30.1-51.4) |

| Median OS (95% CI),‡mo | NR (9.2 to NR) | 22.2 (8.0 to NR) | NR (10.6 to NR) |

| Median follow-up (95% CI),§ mo | 22.0 (18.2-23.7) | 18.3 (11.1-24.05) | 22.0 (18.0-23.6) |

| 6-mo probability of OS, % (95% CI)‡ | 85 (72.3-92.2) | 78 (55.6-90.4) | 83 (72.5-89.7) |

| 12-mo probability of OS, % (95% CI)‡ | 62 (46.5-73.7) | 60 (36.6-76.8) | 61 (48.9-71.5) |

| . | Outpatients (n = 57) . | Inpatients (n = 25) . | Total (N = 82) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall response,∗n (%) | |||

| CR | 33 (58) | 11 (44) | 44 (54) |

| PR | 14 (25) | 8 (32) | 22 (27) |

| SD | 3 (5) | 3 (12) | 6 (7) |

| PD | 7 (12) | 3 (12) | 10 (12) |

| ORR | |||

| CR + PR, n (%) | 47 (82) | 19 (76) | 66 (80) |

| 95% CI† | 70.1-91.3 | 54.9-90.6 | 70.3-88.4 |

| CR rate | |||

| CR, n (%) | 33 (58) | 11 (44) | 44 (54) |

| 95% CI† | 44.1-70.9 | 24.4-65.1 | 42.3-64.7 |

| Median DOR (95% CI),‡mo | 11.1 (3.9 to NR) | NR (2.1 to NR) | 14.75 (5.0 to NR) |

| Median follow-up (95% CI),§ mo | 17.7 (16.95-22.8) | 17.3 (7.75-23.3) | 17.35 (16.95-22.7) |

| 6-mo probability of continued response, % (95% CI)‡ | 54 (38.9-67.3) | 58 (33.2-76.3) | 55 (42.5-66.4) |

| 12-mo probability of continued response, % (95% CI)‡ | 50 (34.6-63.1) | 51 (26.0-70.9) | 50 (37.5-61.8) |

| Median DOR in patients achieving CR (95% CI),‡mo | NR (11.1 to NR) | NR (8.7 to NR) | NR (16.6 to NR) |

| Median follow-up (95% CI),§ mo | 17.4 (16.95-22.8) | 17.3 (7.7-23.5) | 17.7 (16.95-22.8) |

| 6-mo probability of continued response, % (95% CI)‡ | 75 (56.0-86.6) | 91 (50.8-98.7) | 79 (63.5-88.5) |

| 12-mo probability of continued response, % (95% CI)‡ | 68 (49.1-81.6) | 79.5 (39.3-94.5) | 71.5 (55.2-82.7) |

| Median PFS (95% CI),‡mo | 6.05 (2.9 to NR) | 4.3 (2.8 to NR) | 5.8 (3.0-15.6) |

| Median follow-up (95% CI),§ mo | 18.6 (17.8-23.7) | 18.0 (8.5-24.0) | 18.2 (17.8-23.7) |

| 6-mo probability of PFS, % (95% CI)‡ | 51 (37.3-62.9) | 44 (24.5-61.9) | 49 (37.6-59.0) |

| 12-mo probability of PFS, % (95% CI)‡ | 42 (28.6-54.0) | 38.5 (19.5-57.3) | 41 (30.1-51.4) |

| Median OS (95% CI),‡mo | NR (9.2 to NR) | 22.2 (8.0 to NR) | NR (10.6 to NR) |

| Median follow-up (95% CI),§ mo | 22.0 (18.2-23.7) | 18.3 (11.1-24.05) | 22.0 (18.0-23.6) |

| 6-mo probability of OS, % (95% CI)‡ | 85 (72.3-92.2) | 78 (55.6-90.4) | 83 (72.5-89.7) |

| 12-mo probability of OS, % (95% CI)‡ | 62 (46.5-73.7) | 60 (36.6-76.8) | 61 (48.9-71.5) |

All percentages are rounded to whole numbers except those with .5%.

PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

Best disease response recorded from the time of liso-cel infusion until disease progression, end of study, or the start of another anticancer therapy. Best response is assigned according to the following order: CR, PR, SD, PD, not evaluable, or not available. PDs are counted even if determined by clinical assessment only.

Two-sided 95% exact Clopper-Pearson CIs.

Kaplan-Meier method was used to obtain 2-sided 95% CIs.

Reverse Kaplan-Meier method was used to obtain median follow-up and its 95% CIs.

In the total population, the median DOR was 14.75 months (95% CI, 5.0 to not reached [NR]) at a median follow-up of 17.35 months (95% CI, 16.95-22.7; Figure 3A). The median DOR in all patients achieving a best overall response of CR was NR (95% CI, 16.6 to NR). The median PFS was 5.8 months (95% CI, 3.0-15.6) after a median follow-up of 18.2 months (95% CI, 17.8-23.7; Figure 3B). The median OS was NR (95% CI, 10.6 to NR) after a median follow-up of 22.0 months (95% CI, 18.0-23.6; Figure 3C). Response rates, DOR, PFS, and OS by monitoring setting are reported in Table 4 and supplemental Figure 2.

DOR, PFS, and OS (liso-cel–treated set). (A-C) Kaplan-Meier estimates of DOR (A), PFS (B), and OS (C). ∗Kaplan-Meier method was used to obtain 2-sided 95% CIs. †Reverse Kaplan-Meier method was used to obtain median follow-up and its 95% CIs.

DOR, PFS, and OS (liso-cel–treated set). (A-C) Kaplan-Meier estimates of DOR (A), PFS (B), and OS (C). ∗Kaplan-Meier method was used to obtain 2-sided 95% CIs. †Reverse Kaplan-Meier method was used to obtain median follow-up and its 95% CIs.

Cellular kinetics and pharmacodynamics

Among the 73 patients evaluable for cellular kinetic analyses, the median time to CAR T-cell maximum expansion was 10.0 days and was similar in outpatients and inpatients. The median peak CAR T-cell expansion was 24 209 copies per μg, and the median area under the curve for transgene levels from 0 to 28 days after liso-cel infusion was 179 317 days × copies per μg. Both parameters were higher in outpatients than inpatients but with considerable variability among patients (supplemental Table 7). Persistence of the liso-cel transgene was observed long term up to day 730 (6/14 evaluable patients), with similar persistence profiles in outpatients and inpatients (supplemental Table 8). Incidence of B-cell aplasia was observed in ≥92% of all patients between baseline (last measurement before liso-cel infusion) and day 90 and was sustained in the majority of patients (60%) in the total population through day 730, although sample size was limited after day 180. For outpatients and inpatients, the incidence of B-cell aplasia was ≥86% and ≥96% through day 180, respectively (supplemental Table 9).

Discussion

In the OUTREACH study, 82 patients with third-line or later R/R LBCL were treated with liso-cel and monitored for CAR T-cell therapy–related toxicities at US community oncology centers in outpatient and inpatient settings using standard operating procedures and multidisciplinary teams. Safety outcomes were similar between outpatients and inpatients in OUTREACH and were consistent with results from the pivotal TRANSCEND study.8 Additionally, the incidence of tocilizumab and/or corticosteroid use in OUTREACH was similar to historical liso-cel data,8-10 further demonstrating the consistent and favorable safety profile of liso-cel in OUTREACH. No severe (grade ≥3) CRS events were reported, and the incidence of severe NEs was low. Overall, 29% of patients required interventions with tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids for treatment of any-grade CRS or NEs, and the rates of use were similar between outpatients and inpatients. The incidence and type of grade ≥3 TEAEs were generally similar to TRANSCEND, with no new safety signals observed. Of note, the incidence of pyrexia in patients monitored in the inpatient setting (28%) was slightly higher than in outpatients (14%) or in the TRANSCEND study (17%)8; however, the most common reason for inpatient monitoring in OUTREACH was disease characteristics, primarily the risk of tumor lysis syndrome and/or risk of CRS, which may explain this difference. Moreover, liso-cel treatment demonstrated considerable efficacy in both outpatients and inpatients, with an overall ORR of 80%, CR rate of 54%, and durable responses (median DOR, 14.75 months) that were consistent with the TRANSCEND study (ORR, 73%; CR rate, 53%; a median DOR of NR at a median follow-up for DOR of 12.0 months and a median DOR of 23.1 months with a median follow-up for DOR of 23.0 months).8,14 Safety results from OUTREACH are also comparable with results from the JULIET study assessing the efficacy and safety of the CD19-directed, 4-1BB costimulated CAR T-cell therapy tisagenlecleucel in patients with R/R LBCL after ≥2 lines of therapy (n = 111); in JULIET, 27% of patients were treated in the outpatient setting.15 In JULIET (overall population), ORR and CR rate were 52% and 40%, respectively, with grade ≥3 CRS (graded by Penn criteria) and NEs (including events occurring at any time after infusion) occurring in 22% and 14% of patients, respectively.7 In the real-world setting in patients with R/R non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n = 155), tisagenlecleucel treatment resulted in ORR and CR rate of 62% and 39.5%, respectively, with grade ≥3 CRS (graded by the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy criteria) and NEs in 5% and 5%, respectively.16 Patient-reported outcomes in OUTREACH, which showed significantly improved scores from baseline in the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 items for global health status/quality of life, fatigue, and pain after treatment, further supported the efficacy and manageable safety profile of liso-cel administration at community centers with outpatient monitoring.13

Although outcomes after outpatient monitoring after CAR T-cell therapy have been reported from single-center programs17-22 and multicenter retrospective analyses,23 OUTREACH is, to our knowledge, the largest prospective clinical study to date to report outcomes of CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy in outpatients with R/R LBCL. Furthermore, the OUTREACH study was performed at sites that represent diverse types of community medical centers, including both single-entity and dual-entity sites, those with and without FACT accreditation, and sites with and without previous experience in CAR T-cell therapy. Therefore, these results are relevant to a broad range of clinicians, regardless of practice type.

Outpatient monitoring was feasible in appropriate patients in the OUTREACH study due to the manageable safety profile of liso-cel and the stringent outpatient monitoring requirements for both study sites and patients/caregivers. Importantly, sites were required to have standard operating procedures in place for outpatient monitoring and 1 designated hospital for patient care after liso-cel therapy, with staff trained to manage CAR T-cell toxicities, which allowed sites without previous experience with CAR T-cell therapy to participate in OUTREACH. Among patients who were monitored in the inpatient setting, the most common reason for inpatient monitoring was disease characteristics, primarily the risk of tumor lysis syndrome and/or risk of CRS. Although OUTREACH was conducted during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, a low percentage of patients was monitored as inpatients because of concerns or precautions related to COVID-19, allowing for robust assessments of safety and efficacy in a larger group of outpatients.

In OUTREACH, the median duration of an initial hospital stay for outpatients vs inpatients was 6.0 vs 15.0 days, with 25% of outpatients never hospitalized after liso-cel infusion and 18% first admitted >29 days after infusion, which has potential implications on treatment costs for both hospitals and payers as well as patient access to therapy.24,25 Additionally, among outpatients requiring hospitalization, most were admitted >72 hours after the day of liso-cel infusion (median time to initial hospitalization was 5.0 days). Because Medicare inpatient reimbursement applies if admission is necessary within 72 hours of infusion, these data further suggest potential health care utilization cost savings with outpatient monitoring of liso-cel, although additional cost-effectiveness studies are needed. Hospitalization rates in OUTREACH were consistent with historical liso-cel data. In TRANSCEND, 25 of 269 total patients (9%) across 5 US study sites were successfully treated with liso-cel and monitored for CAR T-cell–related toxicity in the outpatient setting.8 Eighteen outpatients (72%) were hospitalized for AEs. The median time from liso-cel infusion to hospitalization was 5 days (range, 3-22); 1 outpatient was admitted to the ICU. Similarly, in the PILOT study (NCT03483103) evaluating liso-cel as second-line treatment in patients with R/R LBCL, including those with older age and more comorbidities, for whom HSCT was not intended, 20 of 61 patients were successfully monitored in the outpatient setting.9 Nine outpatients (45%) were hospitalized, including 7 (35%) for AEs. The median time from liso-cel infusion to hospitalization was 6 days (interquartile range, 5-10); 1 outpatient was admitted to the ICU. In the interim analysis from the TRANSFORM study (NCT03575351), which evaluated liso-cel as second-line therapy vs standard of care in patients with R/R LBCL eligible for HSCT, of 19 patients who received liso-cel in the outpatient setting, 13 patients (68%) were hospitalized, including 10 (53%) for AEs. The median time from liso-cel infusion to hospitalization was 9.0 days (interquartile range, 4-19) after infusion; no outpatients were admitted to the ICU.10

Several study limitations should be noted. Although the incidence of grade ≥3 AESIs was the primary end point and safety in patients monitored in the outpatient setting was a secondary end point, the study was not designed to support comparisons between inpatients and outpatients. OUTREACH was not a randomized study, and inpatient monitoring was solely at the investigator’s discretion. Although baseline patient and disease characteristics were generally similar for outpatients and inpatients, some notable differences suggest that tumor burden may have been higher in patients monitored in the inpatient setting. However, it should be noted that efficacy and safety results appeared similar across outpatients and inpatients, despite these potential baseline differences. Additionally, OUTREACH did not use an independent review committee; response assessments were performed by investigator only.

In summary, liso-cel demonstrated a favorable safety profile in patients with R/R LBCL monitored as outpatients or inpatients, with low incidences of severe CRS or NEs, low use of tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids to manage CRS/NEs, and high response rates that were durable, consistent with results from the pivotal TRANSCEND study. These findings support liso-cel treatment at community medical centers using standard operating procedures and multidisciplinary teams with outpatient monitoring in appropriate patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Adam Omidpanah for assistance with statistical analysis and programming and Josu Santamaria for assistance with data validation and interpretation. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Allison Green of The Lockwood Group (Stamford, CT), funded by Bristol Myers Squibb.

The OUTREACH study was funded by Juno Therapeutics, a Bristol Myers Squibb company.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.L., C.O.F., M.C., C. Bachier, M.M., D.H., J.C.V., C. Bellomo, S.C., J.E., S.F., H.T., H.Y., J.C., and B.M. contributed to data acquisition and interpretation; J.P.S. and A.K. contributed to conception/design, data acquisition, and data interpretation; M.V., K.O., and A.A. contributed to data interpretation and data analysis; R.E. and B.Y. contributed to data interpretation; and all authors contributed to and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Y.L. declares honoraria from Kyowa Kirin; speaker's bureau fees from Kyowa Kirin; advisory board fees from AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, BeiGene USA Inc, Gilead Sciences Inc, GlaxoSmithKline, Seagen Inc, and TG Therapeutics; and research funding from ADC Therapeutics, BeiGene USA Inc, Genentech, and Seagen Inc. M.C. reports advisory board fees from Bristol Myers Squibb. J.C.V. declares consultancy and advisory boards fees from and equity in NexImmune; and speaker's bureau fees from Kite/Gilead. J.E. declares speakers’ bureau fees from Bristol Myers Squibb and Gilead. H.Y. declares employment with Texas Oncology; consultancy fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, and Karyopharm; speakers’ bureau fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, Karyopharm Therapeutics, and Takeda; travel, accommodations, and expenses from Amgen, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, and Karyopharm Therapeutics; divested equity in Epizyme and Karyopharm Therapeutics; and research funding from BeiGene, Janssen, and Takeda. J.P.S. declares consultancy fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, TG Therapeutics, Merck, and Lilly. A.K. declares previous employment with and equity in Bristol Myers Squibb. M.V., K.O., A.A., R.E., and B.Y. declare employment with and equity in Bristol Myers Squibb. B.M. declares speakers’ bureau fees from Gilead and Takeda. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for A.K. is Arcellx, Inc., Redwood City, CA.

Correspondence: Yuliya Linhares, Baptist Health, Miami Cancer Institute, 8900 North Kendall Dr, Miami, FL 33176; email: YuliyaL@baptisthealth.net.

References

Author notes

Presented in part in poster form at the 64th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, New Orleans, LA, 12 December 2022.

Bristol Myers Squibb policy on data sharing may be found at https://www.bms.com/researchers-and-partners/independent-research/data-sharing-request-process.html.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.