Key Points

aMCD belongs to HHV-8–negative MCD, which might be a potential early stage of iMCD.

Patients with aMCD do not need immediate treatment but should be closely monitored.

Visual Abstract

According to the diagnostic criteria for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)–negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD) proposed by Castleman Disease Collaborative Network in 2017, there is a group of HHV-8–negative patients with multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) who do not have symptoms and hyperinflammatory state and do not meet the iMCD criteria. This retrospective study enrolled 114 such patients, described as asymptomatic MCD (aMCD), from 26 Chinese centers from 2000 to 2021. With a median follow-up time of 46.5 months (range, 4-279 months), 6 patients (5.3%) transformed to iMCD. The median time between a diagnosis of aMCD and iMCD in these 6 patients was 28.5 months (range, 3-60). During follow-up, 7 patients died; 3 of them died from progression of MCD. Despite that, 37.7% of patients received systemic treatment targeting MCD; this strategy was neither associated with a lower probability of iMCD transformation nor a lower death rate. The 5-year estimated survival of all patients with aMCD was 94.1% (95% confidence interval, 88.8-99.6). Transformation to iMCD was an important predictor of death (log-rank P = .01; 5-year estimated survival, 83.3%). This study suggests that patients with aMCD may represent a potential early stage of iMCD, who may not require immediate treatment but should be closely monitored.

Introduction

In 2017, Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN) published the first international, evidence-based consensus diagnostic criteria for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)–negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD), a rare and sometimes life-threatening disorder involving systemic inflammatory symptoms, polyclonal lymphoproliferation, cytopenia, and multiple organ system dysfunction.1 According to this consensus, HHV-8–negative multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) was regarded as iMCD due to unknown etiology. This consensus also set the first evidence-based diagnostic criteria for iMCD: after exclusion of diseases that can mimic iMCD, patients who met 2 major criteria (histopathologic evidence and enlarged lymph nodes with short-axis diameter ≥1 cm in ≥2 lymph node stations) and at least 2 of 11 minor criteria (with at least 1 laboratory criterion) were diagnosed as iMCD.1 However, there was a group of HHV-8–negative patients who met the major criteria but did not have symptoms and hyperinflammatory state and thus did not meet the minor criteria for iMCD proposed by CDCN. These patients could be classified as HHV-8–negative MCD but could not be diagnosed as iMCD according to the current diagnostic criteria. In a recently published retrospective study, this group of patients, who were described as asymptomatic MCD (aMCD), could comprise up to 19.3% of all HHV-8–negative patients with MCD.2 It remains unclear whether this subgroup of patients represents a “prestage” of iMCD, who will eventually develop clinical and laboratory abnormalities over time, or if they belong to a distinct subset of patients with MCD. Herein, we conducted a multicenter, retrospective study that focused on the follow-up information and potential transformation of patients with aMCD, to determine whether they would eventually have inflammatory symptoms and laboratory abnormalities and “transformed” to iMCD.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted this observational, retrospective study that enrolled patients with aMCD from 2000 to 2021 in 26 medical centers in China. These medical centers, which had experience in the diagnosis and treatment of Castleman disease (CD), were the referral hospitals of their located provincial-level administrative regions. The inclusion criteria for patients with aMCD were HHV-8–negative patients with MCD who met both major criteria mentioned above (histopathologic evidence plus ≥2 lymph node stations involvement) but did not meet the minimal requirements of the minor diagnostic criteria (at least 2 of 11 minor criteria with ≥1 laboratory criterion) proposed by CDCN.1 HHV-8 status was confirmed by blood polymerase chain reaction or latency-associated nuclear antigen-1 staining by immunohistochemistry. The major criteria the patients needed to meet for inclusion were (1) histopathologic lymph node features consistent with the iMCD spectrum (an example is shown in the supplemental Material); and (2) enlarged lymph nodes (≥1 cm in short-axis diameter) in ≥2 lymph node stations. Patients with lymph node involvement on the same side of the diaphragm were also included if the abovementioned criteria were fulfilled. Patients with underlying diseases such as infection-related disorders (eg, HIV infection), autoimmune diseases, and malignant/lymphoproliferative disorders (eg, POEMS [polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal protein, skin changes] syndrome), which could mimic MCD, were excluded from this study. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data, including age, sex, medical history, histopathologic subtypes, clinical symptoms, radiological findings, and treatment at the stage of aMCD, were retrieved from medical records. Patient follow-up information was collected from medical record systems and through telephone contacts. Patients were followed until 31 March 2023. The time point when a patient developed symptoms and/or new laboratory abnormalities and met the CDCN diagnostic criteria for iMCD was recorded. Moreover, the survival status was also documented. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with prior approval of the institutional review board and the ethics committee of the local hospital.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the transformation rate of aMCD to iMCD. “Transformation” was documented when a patient fulfilled at least 2 of the 11 minor criteria (with at least 1 laboratory criterion) for iMCD proposed by CDCN1 who was then diagnosed as iMCD. Other study outcomes included description of demographic features and treatment options, the time interval between diagnosis of aMCD and iMCD, and overall survival, which was defined as the time interval between diagnosis and either death or the last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 22 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were used for demographics, pathological subtypes, and treatment options. Frequencies and percentages were presented for categorical variables; medians and ranges were presented for continuous data. χ2 tests and t tests were used to compare dichotomous variables and continuous variables, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to depict survival curves, and the log-rank test was used to compare the survival curves.

Results

A total of 114 patients were enrolled. All patients were HIV negative. Among them, 60 (52.6%) were males, and 54 (47.4%) were females. The median age at diagnosis of aMCD was 45.5 years (range, 10-79). Adult patients (age ≥18 years) accounted for 92.1%. There were 93 patients who had pathological subtype information: 55 patients (59.1%) had hyaline vascular (HV) histopathological subtype, 24 patients (25.8%) had plasmacytic subtype, and 14 patients (15.1%) had mixed histopathological subtype. Twenty-four patients (21.1%) had both supradiaphragmatic and infradiaphragmatic involvement. After the diagnosis of MCD, although the patients did not have inflammatory symptoms or laboratory abnormalities, 43 patients (37.7%) received treatment targeting MCD (Table 1). Notably, the majority of these asymptomatic patients received lymphoma-like intensive chemotherapy (eg, CHOP [cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone] and R-CHOP [rituximab-CHOP]).

Treatment options for patients with aMCD

| . | No. of patients . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| CHOP and CHOP-like | 18 | 41.9 |

| R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like/R plus glucocorticoids | 10 | 23.3 |

| TCP/TCD/TD | 5 | 11.6 |

| BCD/BD | 2 | 4.7 |

| Lenalidomide-based therapy | 2 | 4.7 |

| Tocilizumab plus glucocorticoids | 1 | 2.3 |

| Glucocorticoids monotherapy | 2 | 4.7 |

| Other combination therapy | 3 | 7.0 |

| . | No. of patients . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|

| CHOP and CHOP-like | 18 | 41.9 |

| R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like/R plus glucocorticoids | 10 | 23.3 |

| TCP/TCD/TD | 5 | 11.6 |

| BCD/BD | 2 | 4.7 |

| Lenalidomide-based therapy | 2 | 4.7 |

| Tocilizumab plus glucocorticoids | 1 | 2.3 |

| Glucocorticoids monotherapy | 2 | 4.7 |

| Other combination therapy | 3 | 7.0 |

BCD, bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone; BD, bortezomib and dexamethasone; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; R, rituximab; TCD, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone; TCP, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone; TD, thalidomide and dexamethasone.

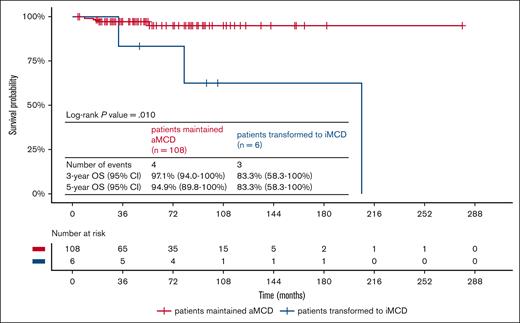

With a median follow-up time of 46.5 months (range, 4-279), 6 patients (5.3%) transformed to iMCD. Of note, there was no “prodrome period.” At the time of transformation to iMCD, all of these patients met at least 3 minor criteria (with at least 2 laboratory criteria), whereas the CDCN diagnostic criteria for iMCD only required 2 minor criteria with at least 1 laboratory criteria.1 Constitutional symptoms and elevated CRP or erythrocyte sedimentation rate were seen in all 6 transformed patients (100%). Anemia was observed in 4 patients (66.7%; Table 2). The median time between the diagnosis of aMCD and iMCD in these 6 patients was 28.5 months (range, 3-60). Sex, age at the diagnosis of aMCD, extent of lymph node involvement, pathological subtype, and systemic therapy targeting MCD were not associated with the probability of transformation to iMCD in these patients with aMCD (Table 3). During the follow-up period, 7 patients died. The 5-year estimated survival of all patients with aMCD in our cohort was 94.1% (95% confidence interval, 88.8-99.6). The median time between the diagnosis of aMCD and death of the 7 patients was 33 months (range, 7-207). Three patients (42.9%), all among those who transformed to iMCD, died from CD. The other 4 patients (57.1%) died from diseases not related to CD. A comparison of clinical features between patients who died and who survived by the end of follow-up showed that transformation to iMCD was an important predictor of death (Table 4). The survival curves showed that patients who transformed to iMCD had a significantly shorter survival (log-rank P = .01; Figure 1). The 5-year estimated survival rate of patients who maintained aMCD was 94.9%, whereas the 5-year estimated survival rate (calculated from the diagnosis of aMCD) of patients who ultimately transformed to iMCD was 83.3%. Of note, no patients were later diagnosed with diseases mimicking MCD (eg, infections, autoimmune diseases, and lymphoproliferative disorders) during follow-up.

Symptoms and laboratory abnormalities in patients who transformed to iMCD

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . | Patient 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated CRP or ESR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Anemia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis | Yes | |||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Renal dysfunction | Yes | |||||

| Constitutional symptoms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Large spleen and/or liver | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Fluid accumulation (edema, ascites, etc) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . | Patient 4 . | Patient 5 . | Patient 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated CRP or ESR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Anemia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Thrombocytopenia or thrombocytosis | Yes | |||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Renal dysfunction | Yes | |||||

| Constitutional symptoms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Large spleen and/or liver | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Fluid accumulation (edema, ascites, etc) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

CRP, c-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Comparison of baseline characteristics of patients who maintained aMCD and transformed to iMCD

| . | Patients who maintained aMCD . | Patients who transformed to iMCD . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male, n (%) | 55 (50.9%) | 5 (8.3%) | .122 |

| Age at diagnosis of aMCD, y | 43.2 ± 15.8 | 48.5 ± 21.3 | .436 |

| Involvement of both sides of the diaphragm, n (%) | 24 (22.2%) | 3 (50.0%) | .119 |

| HV subtype, n (%) | 53 (59.6%) | 2 (50.0%) | .704 |

| Receiving treatment for aMCD, n (%) | 40 (37.0%) | 3 (50.0%) | .524 |

| . | Patients who maintained aMCD . | Patients who transformed to iMCD . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male, n (%) | 55 (50.9%) | 5 (8.3%) | .122 |

| Age at diagnosis of aMCD, y | 43.2 ± 15.8 | 48.5 ± 21.3 | .436 |

| Involvement of both sides of the diaphragm, n (%) | 24 (22.2%) | 3 (50.0%) | .119 |

| HV subtype, n (%) | 53 (59.6%) | 2 (50.0%) | .704 |

| Receiving treatment for aMCD, n (%) | 40 (37.0%) | 3 (50.0%) | .524 |

Comparison of clinical features of patients with aMCD who died vs those who survived

| . | Survivor patients . | Deceased patients . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male, n (%) | 57 (53.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | .593 |

| Age at diagnosis of aMCD, y | 50.7 ± 18.9 | 43.0 ± 15.9 | .222 |

| Involvement of both sides of the diaphragm, n (%) | 24 (22.4%) | 3 (42.9%) | .218 |

| HV subtype, n (%) | 53 (60.3%) | 2 (40.0%) | .371 |

| Receiving treatment for aMCD, n (%) | 42 (39.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | .187 |

| Transformation to iMCD, n (%) | 3 (2.8%) | 3 (42.9%) | <.001 |

| . | Survivor patients . | Deceased patients . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male, n (%) | 57 (53.3%) | 3 (42.9%) | .593 |

| Age at diagnosis of aMCD, y | 50.7 ± 18.9 | 43.0 ± 15.9 | .222 |

| Involvement of both sides of the diaphragm, n (%) | 24 (22.4%) | 3 (42.9%) | .218 |

| HV subtype, n (%) | 53 (60.3%) | 2 (40.0%) | .371 |

| Receiving treatment for aMCD, n (%) | 42 (39.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | .187 |

| Transformation to iMCD, n (%) | 3 (2.8%) | 3 (42.9%) | <.001 |

Survival curves of patients who maintained aMCD and those who transformed to iMCD. CI, confidence interval.

Survival curves of patients who maintained aMCD and those who transformed to iMCD. CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Previous literatures have treated HHV-8–negative MCD equally as iMCD.1,3-5 However, a proportion of patients with HHV-8–negative MCD did not meet the minimal minor diagnostic criteria proposed by CDCN.2 These patients have multiple lymph node involvement with histopathological features consistent with CD and no evidence of HHV-8 infection; thus, they could be classified as HHV-8–negative MCD. However, these patients do not have inflammatory symptoms and laboratory manifestations and could not be diagnosed as iMCD. In 2021, the Chinese consensus of the diagnosis and treatment of CD named this subgroup of patients as aMCD6; however, there were no evidence to support whether this group of patients represented a “prestage” of iMCD or belonged to a unique subgroup of MCD. To our knowledge, this was the first study that focused on patients with aMCD. With a median follow-up of almost 4 years, 5.3% patients transformed to iMCD. The fact that some patients would transform to iMCD during the follow-up time suggested that aMCD might be a potential early stage of iMCD. Moreover, this low rate of transformation (5.3%) over a relatively long time span also suggested that aMCD may be considered a unique subset of HHV-8–negative MCD in the future. Awareness of these facts is crucial, because it can help patients avoid unnecessary treatment. As revealed from our cohort, early initiation of treatment while patients were still asymptomatic neither prevented transformation to iMCD nor provided a protective effect against death.

Similar to iMCD7 (59.1% male vs 40.9% female), a slight male predominance (52.6% vs 47.4%) was observed in this aMCD cohort. However, the proportion of patients with aMCD who had HV histopathological subtype (59.1%) seems to be higher than that of patients with iMCD.8 However, a prior study5 also showed similar distribution of HV subtype in patients with iMCD (51.62%). Moreover, according to our findings, the distribution of pathological subtypes was not associated with the probability of transformation to iMCD (Table 3). These findings also support the viewpoint that aMCD may represent a potential early stage of iMCD. Although not statistically significant, there was a trend indicating that patients with involvement confined to 1 side of diaphragm had a lower possibility of transformation to iMCD (P = .119; Table 3). Future studies with more patients with aMCD may provide a more conclusive result.

In 2021, Pierson et al noticed a group of patients who met both major criteria for iMCD proposed by CDCN but had lymph node involvement on the same side of the diaphragm.9 These patients, defined as oligocentric CD (OCD), were found to have “symptoms and laboratory abnormalities more comparable with unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) than iMCD.” Although the authors did not specify whether these patients met the minor criteria for iMCD diagnosis, their statement that “symptoms and laboratory abnormalities were comparable with UCD” suggested that at least a portion of the patients with OCD mentioned in that study might meet the definition of aMCD used in our research. Although some of the patients with aMCD in our study also met the OCD criteria according to Pierson et al,9 we believe the term “aMCD” may be more appropriate than “OCD” for the following reasons. Firstly, even those patients who seemed to meet the diagnostic criteria for OCD still had a similar risk of transformation to iMCD (developing symptoms and laboratory abnormalities). As shown in Table 3, three of the 6 patients (50.0%) who eventually transformed to iMCD had lymph node involvement on the same side of the diaphragm (OCD). This finding suggested that OCD might also be a potential early stage of iMCD. Secondly, the term “OCD” might be misleading, especially when focusing on the treatment strategy. Because the authors mentioned that OCD was similar to UCD, which is curable with surgery in most cases, this could lead doctors to pursue more aggressive surgical procedures for patients with OCD. However, as shown in our study, most patients remained asymptomatic and did not require surgery; and even the small portion of patients who transformed to iMCD were not candidates for aggressive surgical treatment. Thirdly, the definition of OCD does not include a group of patients with aMCD with lymph node involvement on both sides of the diaphragm.

Patients who transformed to iMCD had a worse prognosis, with an estimated 5-year survival of 83.3%, which is comparable with patients with iMCD (84%).10 This finding suggests that patients with iMCD who “transformed” from aMCD have a similar disease process as other patients with iMCD, further supporting the idea that aMCD might be considered a potential early stage of iMCD. Moreover, the fact that patients with aMCD who transformed to iMCD had much worse outcomes necessitates close follow-up of patients with aMCD.

In summary, aMCD may be regarded as a potential early stage of iMCD that does not require immediate treatment but should be closely monitored.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dongcheng District Outstanding Talent Nurturing Program (grant 2022-dchrcpyzz-69) (L.Z.), the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (grant 2022-PUMCH-A-021) (L.Z.), the Research and Translation Application of Beijing Clinical Diagnostic Technologies Funds from Beijing Municipal Commission of Science and Technology (grant Z211100002921016) (L.Z.), and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (grant 2021-1-I2M-019) (J.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: J.L. and L.Z. designed the study; L.Z., Q.-h.L., H.Z., H.-l.Z., Y.-j.D., X.-b.W., L.-q.W., L.-p.S., X.-j.Y., Y.L., M.-z.Z., K.-y.D., H.-h.W., H.-l.P., L.-y.Z., L.Y., L.-t.B., D.G., G.-x.G., L.H., C.-y.S., J.S., W.-b.Q., W.-r.H., Z.-l.L, Y.L., and J.L. enrolled patients and collected data; L.Z., Q.-h.L., H.Z., and J.L. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; and all authors had access to primary data and gave final approval to submit for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jian Li, Department of Hematology and State Key Laboratory of Complex Severe and Rare Diseases, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, No. 1 Shuaifuyuan, Dongcheng District, Beijing 100730, China; email: lijian@pumch.cn.

References

Author notes

L.Z., Q.-h.L., and H.Z. are joint first authors.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, Jian Li (lijian@pumch.cn).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.