Key Points

Recombinant DENV NS1 activates platelets, partially reproducing the inflammatory pathways of DENV-infected platelets.

DENV-induced platelet activation requires viral genome translation and engagement of NS1 through an autocrine loop.

Abstract

Emerging evidence identifies major contributions of platelets to inflammatory amplification in dengue, but the mechanisms of infection-driven platelet activation are not completely understood. Dengue virus nonstructural protein-1 (DENV NS1) is a viral protein secreted by infected cells with recognized roles in dengue pathogenesis, but it remains unknown whether NS1 contributes to the inflammatory phenotype of infected platelets. This study shows that recombinant DENV NS1 activated platelets toward an inflammatory phenotype that partially reproduced DENV infection. NS1 stimulation induced translocation of α-granules and release of stored factors, but not of newly synthesized interleukin-1β (IL-1β). Even though both NS1 and DENV were able to induce pro-IL-1β synthesis, only DENV infection triggered caspase-1 activation and IL-1β release by platelets. A more complete thromboinflammatory phenotype was achieved by synergistic activation of NS1 with classic platelet agonists, enhancing α-granule translocation and inducing thromboxane A2 synthesis (thrombin and platelet-activating factor), or activating caspase-1 for IL-1β processing and secretion (adenosine triphosphate). Also, platelet activation by NS1 partially depended on toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4), but not TLR-2/6. Finally, the platelets sustained viral genome translation and replication, but did not support the release of viral progeny to the extracellular milieu, characterizing an abortive viral infection. Although DENV infection was not productive, translation of the DENV genome led to NS1 expression and release by platelets, contributing to the activation of infected platelets through an autocrine loop. These data reveal distinct, new mechanisms for platelet activation in dengue, involving DENV genome translation and NS1-induced platelet activation via platelet TLR4.

Introduction

Dengue is an arthropod-borne viral disease transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes and caused by 1 of 4 dengue virus serotypes (dengue virus-1 [DENV-1] to DENV-4).1,2 Dengue has become a serious health issue worldwide because of its rapid dissemination, high incidence, and severity.1 According to the World Health Organization,3 half of the world’s population is at risk of contracting dengue. DENV-infected individuals may manifest as asymptomatic infections or progress to a mild or severe dengue syndrome.4 Although dengue is self-limiting, patients with severe dengue present life-threatening manifestations including severe vascular leakage, hemorrhage, organ failure, and shock.4 Thrombocytopenia is a hallmark of dengue, and its prevalence and severity are higher in severe cases.5

Even though the precise mechanisms leading to severe dengue are not fully elucidated, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines contribute to hemodynamic instability and disease severity.6-8 Platelets from patients with dengue present features of increased activation, which are greater in severe dengue.9,10 A previous study by our group has shown that activated platelets from dengue-infected patients or platelets infected with DENV in vitro assemble the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine rich repeat, and pyrin domain containing-3 (NLRP3)-inflammasome complex, leading to increased secretion of interleukin-1β (IL-1β).11 In that study, IL-1β synthesis and secretion by platelets correlated with increased vascular permeability, and DENV-infected platelets increased endothelial permeability in vitro through the interleukin-1 receptor.11 Furthermore, platelets from patients with dengue or platelets infected with DENV in vitro also express P-selectin and release granule-stored chemokines, amplifying inflammation in dengue.9,12-16 Nevertheless, infection-triggered inflammatory pathways in platelets are not completely understood.

Recent studies have demonstrated that DENV-infected platelets can replicate the viral genome and to translate it into proteins, including DENV nonstructural protein-1 (NS1).17,18 NS1 is a glycoprotein that comprises the DENV replication complex together with other NS proteins.19 Moreover, NS1 is the only NS protein that is secreted into the extracellular milieu.20 Serum levels of secreted NS1 in patients correlate with severe dengue.21 Recently, it has been reported that DENV NS1 acts as a viral pathogen-associated molecular pattern that activates toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on leukocytes and endothelial cells leading to inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.22-24 A recent study has demonstrated that NS1 can also activate platelets, thus initiating prothrombotic responses.25 However, it remains unknown whether NS1 triggers inflammatory responses in platelets and whether its synthesis and secretion are necessary for the inflammatory phenotype of infected platelets. Our study showed that platelet NS1 translation and secretion drive inflammatory amplification in DENV infection and revealed the mechanisms involved in cytokine synthesis and secretion by DENV- or NS1-activated platelets.

Material and methods

Human subjects

Peripheral vein blood was obtained from healthy volunteers, as approved by the Institutional Review Board of Federal University of Juiz de Fora (HU-UFJF, 2.223.542). All participants volunteered by written informed consent before any experimental procedure.

Platelet isolation

Platelets were isolated as previously described.11 Blood samples were drawn into acid-citrate-dextrose and centrifuged (200g, 20 minutes) at room temperature. Platelet-rich plasma was recovered, 100 nM of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1; Cayman 13010) was added, and the platelet-rich plasma was recentrifuged (500g, 20 minutes) to pellet the platelets. Platelets were resuspended in 2.5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4; pH 7.4) containing 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% human serum albumin, and 100 nM PGE1, and incubated with anti-CD45 tetramers (1:200, 10 minutes), followed by dextran-coated magnetic beads (1:100, 15 minutes) for removal of leukocytes in a magnetic field (human CD45+ depletion kit; 18259; StemCell). Leukocyte-depleted platelets were resuspended in 25 mL of PSG (5 mM PIPES, 145 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 50 μM Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2·6H2O, and 5.5 mM glucose; pH 6.8), containing 100 nM PGE1, and centrifuged (500g, 20 minutes) at room temperature. Platelets were resuspended in medium 199 (M199; 12-117F; Lonza; or 1155735; Gibco) supplemented with N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (15630-080; Gibco), and the concentration of platelets was adjusted to 109/mL.

In vitro platelet stimulation

Platelets were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of DENV2 NS1 produced in Escherichia coli expression system,26 in SF9 insect cells transfected by using the BaculoDirect expression system (10359-016; Invitrogen), or commercially available NS1 produced in HEK293 cells (ab191866; Abcam), for 1.5 to 3 hours, at 37°C. To eliminate the possibility of LPS contamination, platelets were stimulated with NS1 or LPS (L3129; Sigma) in the presence of polymyxin B (Invivogen).

To investigate the receptors involved in NS1-induced platelet activation, platelets were pretreated (30 minutes) with neutralizing antibodies (20 µg/mL) against TLR4 (169917-82; eBioscience), TLR2 (6C2; Thermo Fisher), TLR6 (sc-5662; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), TLR4/MD2 (169924-81; eBioscience) or isotype-matched IgG, or with TLR6 binding peptide (sc-5662P; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) before NS1 stimulation.

We investigated whether DENV2 NS1 synergizes with classic agonists by stimulating platelets, treated or not with aspirin (100 μM; A5376; Sigma), with NS1 for 2.5 hours and further with suboptimal concentrations of thrombin (0.05 U/mL), platelet activating factor (PAF; 40 nM), oxLDL (5 µg/mL), epinephrine (10 µM), or adenosine triphosphate (ATP; 2 mM) for 30 minutes at 37°C. To evaluate IL-1β secretion by NS1-stimulated platelets, the classic inflammasome trigger ATP (5 mM) was used in addition to NS1.

DENV production and purification

DENV2 strain 16881 was propagated in C6/36 Aedes albopictus cells and titrated by plaque assay, as previously reported.27 DENV2 was purified between 50% and 20% (weight to weight) sucrose gradient in phosphate-buffered saline, as previously described28,29 and detailed in the supplemental Methods (supplemental Figure 1).

Platelet infection with DENV2

Platelets were infected with DENV2 in a multiplicity of infection of 1 (MOI = 1) and incubated at 37°C. One hour and 30 minutes after infection, platelets were washed 3 times with M199 to remove unbound viruses. At 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours after infection, platelet pellets and supernatants were recovered for analysis of DENV2 RNA replication, synthesis and secretion of NS1, and platelet activation. To investigate the participation of ATP from dense granules in DENV-induced caspase-1 activation, platelets were treated with 5 μM of the P2X7 antagonist Brilliant Blue G (BBG, B0770; Sigma).

Flow cytometric analysis

The platelets were labeled with allophycocyanin-, or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CD41, and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD62P or anti-CD63 antibodies (BD Pharmingen) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Isotype-matched IgG conjugated with the same fluorochromes were used as the negative control. To determine caspase-1 activation, we labeled the platelets with a fluorescent inhibitor of caspase-1 (FAM-YVAD), centrifuged the cells (1000g for 10 minutes), washed the cells 3 times in the supplier’s washing buffer, labeled them with anti-CD41 as above, and fixed them according to the manufacturer’s instructions (ImmunoChemistry Technologies). Flow cytometer (BD FACSCanto II, BD FACSCalibur, or BD FACSVerse) was used to acquire 10 000 CD41+ events. Data were further analyzed with FlowJo software.

Fluorescent LPS competition assay

In order to evaluate NS1 binding to TLR4, platelets were labeled with FITC-conjugated LPS (5 µg/mL) in the presence of NS1 at increasing concentrations (0-50 μg/mL) for 5 minutes at room temperature. A control competition assay was performed between LPS-FITC (5-10 µg/mL) and unconjugated LPS (0-10 µg/mL). Fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Western blot analysis

Platelets were subjected to lysis in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail (ROCHE), and proteins from cell lysates or platelet supernatants were analyzed through western blot as detailed in the supplemental Material. Primary antibodies used in this study were rabbit anti-NS1 (Invitrogen PA5-32207), rabbit anti-IL-1β (Santa Cruz sc-7884), mouse anti-β-actin (Sigma), and rabbit anti-capsid, obtained as previously reported.30

Viral RNA quantification

The DENV-2 RNA was extracted from supernatants or platelet lysates by using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini-Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed with the QuantiNova Probe RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen) on a PRISM 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems), as described in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

All statistics were performed with GraphPad Prism 7 software. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to analyze whether numerical variables followed a normal distribution. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare ≥3 groups and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used to analyze the differences between the groups. The effect of polymyxin B over the effect of NS1 or LPS was assessed using 2-way ANOVA, and the locations of the differences were identified by Fisher’s exact test. Comparisons between 2 groups were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test, for nonparametric distributions, or the Student t test, for parametric distributions.

Results

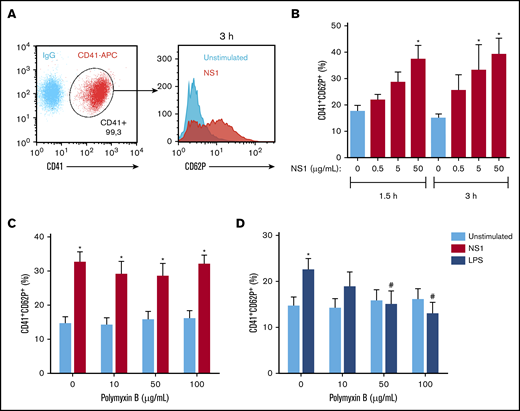

NS1 activates platelets inducing the secretion of stored mediators

To investigate whether DENV NS1 activates platelets, we analyzed P-selectin surface translocation on platelets exposed to recombinant DENV2 NS1 derived from an E coli expression system.26 Our results showed a significant increase in P-selectin surface expression after 1.5- to 3-hour stimulation (Figure 1A-B). Polymyxin B, an LPS chelator, did not prevent NS1-induced platelet activation (Figure 1C), but did inhibit platelet activation by LPS (Figure 1D). These data exclude possible activation by contaminating LPS and support NS1-induced platelet activation.

DENV NS1 activates platelets. (A) Gating strategy for analysis of P-selectin (CD62P) expression on CD41+ platelets. (B) Platelets from healthy donors were incubated with 0, 0.5, 5, and 50 μg/mL of NS1 for 1.5 or 3 hours. (C-D) Platelets were stimulated with 50 μg/mL of NS1 (C) or 10 μg/mL of LPS (D) for 3 hours in the presence of 0, 10, 50, or 100 μg/mL polymyxin B. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05, compared with unstimulated platelets in the same time frame; #P < .05 between platelets treated or not with polymyxin B.

DENV NS1 activates platelets. (A) Gating strategy for analysis of P-selectin (CD62P) expression on CD41+ platelets. (B) Platelets from healthy donors were incubated with 0, 0.5, 5, and 50 μg/mL of NS1 for 1.5 or 3 hours. (C-D) Platelets were stimulated with 50 μg/mL of NS1 (C) or 10 μg/mL of LPS (D) for 3 hours in the presence of 0, 10, 50, or 100 μg/mL polymyxin B. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05, compared with unstimulated platelets in the same time frame; #P < .05 between platelets treated or not with polymyxin B.

Depending on the stimulus, activated platelets release a wide range of stored or newly synthesized factors.31-35 Among them, platelet-derived cytokines and chemokines have been linked to vasculopathy and severity in dengue.8,9,11 Hence, we wanted to investigate the secretory pathways activated in NS1-stimulated platelets. Our results demonstrate that NS1 increased the secretion of the granule-stored chemokines PF4/CXCL4 and RANTES/CCL5 (Figure 2A-B) and the stored inflammatory cytokine MIF (Figure 2C), but not the newly synthesized cytokine IL-1β (Figure 2D). As previously reported,11 DENV infection induced IL-1β secretion by platelets (Figure 2D). Polymyxin B did not inhibit platelet secretion after NS1 stimulation, but did inhibit LPS-induced PF4/CXCL4 secretion (supplemental Figure 2). Taken together, these results show that DENV2 NS1 activates platelets and induces the secretion of stored chemokines and cytokines.

NS1 induces the secretion of granule-stored mediators but not newly synthesized IL-1β. Platelets from healthy donors were stimulated with NS1 (0, 0.5, 5, or 50 μg/mL) for 1.5 or 3 hours. Concentrations of the chemokines PF4/CXCL4 (A) and RANTES/CCL5 (B), and the cytokines MIF (C) and IL-1β (D) were quantified in platelet supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Platelets stimulated with DENV2 (MOI = 1) for 3 hours were used as the positive control for IL-1β secretion. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with unstimulated platelets at the same time frame.

NS1 induces the secretion of granule-stored mediators but not newly synthesized IL-1β. Platelets from healthy donors were stimulated with NS1 (0, 0.5, 5, or 50 μg/mL) for 1.5 or 3 hours. Concentrations of the chemokines PF4/CXCL4 (A) and RANTES/CCL5 (B), and the cytokines MIF (C) and IL-1β (D) were quantified in platelet supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Platelets stimulated with DENV2 (MOI = 1) for 3 hours were used as the positive control for IL-1β secretion. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with unstimulated platelets at the same time frame.

NS1 from insect or mammalian cells activates platelets

We showed that recombinant DENV2 NS1 produced in bacteria activates platelets. Moreover, it was recently shown that NS1 expressed by insect cells also induces platelet activation.25 Considering that the high levels of NS1 in patients’ blood derive from viral replication in host (mammalian) cells, we sought to investigate whether DENV NS1, expressed and folded by mammalian cells, also activates platelets. Therefore, we compared platelets stimulated by E coli–derived NS1with NS1 produced by insect SF9 or mammalian HEK293 cells. Likewise, NS1 secreted by insect or mammalian cells significantly increased P-selectin surface translocation (Figure 3A). Similarly, platelet stimulation with mammal- or arthropod-derived NS1 increased the secretion of RANTES/CCL5 and MIF (Figure 3B-C), but not newly synthesized IL-1β (Figure 3D). Infection with DENV activated platelet secretory pathways with release of both stored and newly synthesized cytokines (Figure 3B-D). These data demonstrate that stimulation with NS1 partially reproduces the phenotype of DENV-infected platelets, inducing the release of stored factors, but not newly synthesized IL-1β.

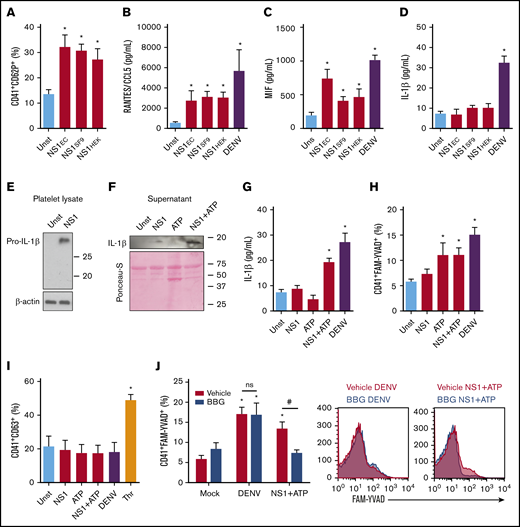

Stimulation with NS1 partially reproduces the inflammatory pathways of DENV-infected platelets. (A-D) Platelets from healthy volunteers were kept unstimulated (Unst) or stimulated with NS1 (5 µg/mL) produced by transfected E coli (NS1EC), mammalian HEK cells (NS1HEK), or insect SF9 cells (NS1SF9) or were infected with DENV (MOI = 1) for 3 hours. (A) The percentage of P-selectin (CD62P) surface expression on platelets; and the concentrations of RANTES/CCL5 (B), MIF (C), and IL-1β (D) in platelet supernatants were evaluated. (E-I) Platelets were stimulated with NS1 produced in SF9 cells (5 µg/mL) and/or ATP (5 mM) or infected with DENV (MOI = 1) for 3 hours. The expression of pro-IL-1β and β-actin in platelet lysates (E); the expression of IL-1β in platelet supernatants (F); the concentration of IL-1β in platelet supernatants (G); labeling of active caspase-1 in intact platelets (H); and the percent of platelet CD63 surface expression (I) were evaluated in each condition. Platelets stimulated with thrombin (Thr, 0.5 U/mL) were used as the positive control for CD63 expression. (J) Platelets were infected with DENV or stimulated with NS1+ATP in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle) or BBG. Caspase-1 activity was evaluated in each condition. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 to 10 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with unstimulated; #P < .05 between platelets treated with vehicle or BBG. ns, nonsignificant.

Stimulation with NS1 partially reproduces the inflammatory pathways of DENV-infected platelets. (A-D) Platelets from healthy volunteers were kept unstimulated (Unst) or stimulated with NS1 (5 µg/mL) produced by transfected E coli (NS1EC), mammalian HEK cells (NS1HEK), or insect SF9 cells (NS1SF9) or were infected with DENV (MOI = 1) for 3 hours. (A) The percentage of P-selectin (CD62P) surface expression on platelets; and the concentrations of RANTES/CCL5 (B), MIF (C), and IL-1β (D) in platelet supernatants were evaluated. (E-I) Platelets were stimulated with NS1 produced in SF9 cells (5 µg/mL) and/or ATP (5 mM) or infected with DENV (MOI = 1) for 3 hours. The expression of pro-IL-1β and β-actin in platelet lysates (E); the expression of IL-1β in platelet supernatants (F); the concentration of IL-1β in platelet supernatants (G); labeling of active caspase-1 in intact platelets (H); and the percent of platelet CD63 surface expression (I) were evaluated in each condition. Platelets stimulated with thrombin (Thr, 0.5 U/mL) were used as the positive control for CD63 expression. (J) Platelets were infected with DENV or stimulated with NS1+ATP in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle) or BBG. Caspase-1 activity was evaluated in each condition. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 to 10 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with unstimulated; #P < .05 between platelets treated with vehicle or BBG. ns, nonsignificant.

NS1 induces pro-IL-1β synthesis, but not caspase-1–dependent IL-1β release

As NS1 did not induce IL-1β secretion by platelets, we sought to investigate whether DENV NS1 induces pro-IL-1β synthesis and whether a second signal is necessary for its secretion. To that end, we analyzed IL-1β expression in platelet lysates and supernatants. NS1 induced pro-IL-1β synthesis, even though no increase was observed in IL-1β secretion (Figure 3E-G). To learn whether a second signal induces IL-1β secretion after NS1 stimulation, we stimulated platelets with NS1 and/or ATP, a classic NLRP3-inflammasome activator.36,37 Stimulation with NS1+ATP induced IL-1β release by platelets (Figure 3F-G). To confirm inflammasome activation in this condition, we analyzed caspase-1 activity. We observed increased caspase-1 activation in platelets stimulated with ATP, NS1+ATP, or DENV, but not in platelets stimulated with NS1 alone (Figure 3H). These data show that NS1 induces pro-IL-1β synthesis in platelets but does not induce capase-1 activation for IL-1β processing and secretion, whereas DENV infection provides all necessary signals for IL-1β synthesis, caspase-1 activation, and IL-1β release (Figure 3G-H).

We then investigated whether ATP released from dense granules is essential for inflammasome activation in DENV-infected platelets. Labeling of CD63 surface expression, a marker of dense granules release, showed no increase in translocation of dense granules upon DENV infection (Figure 3I). Consistently, pretreatment with the P2X7 inhibitor BBG did not decrease caspase-1 activity in DENV-infected platelets (Figure 3J), excluding ATP-dependent caspase-1 activation.

DENV NS1 amplifies thromboinflammatory responses induced by classic agonists

We then investigated whether NS1 sensitizes platelets to activation by subthreshold concentrations of classic agonists. As already described, stimulation with NS1 significantly increased platelet activation (Figure 4A). Furthermore, preexposure to NS1 potentiated P-selectin surface translocation after PAF, thrombin, or epinephrine, but not after oxLDL or ATP stimulation (Figure 4A). Similarly, the secretion of MIF was induced by NS1 or classic agonists alone, whereas a synergistic effect was observed with PAF, thrombin, and epinephrine, but not oxLDL (Figure 4B). Similar results were obtained for P-selectin, PF4/CXCL4, and MIF in platelets preexposed to bacteria-derived NS1 (supplemental Figure 3).

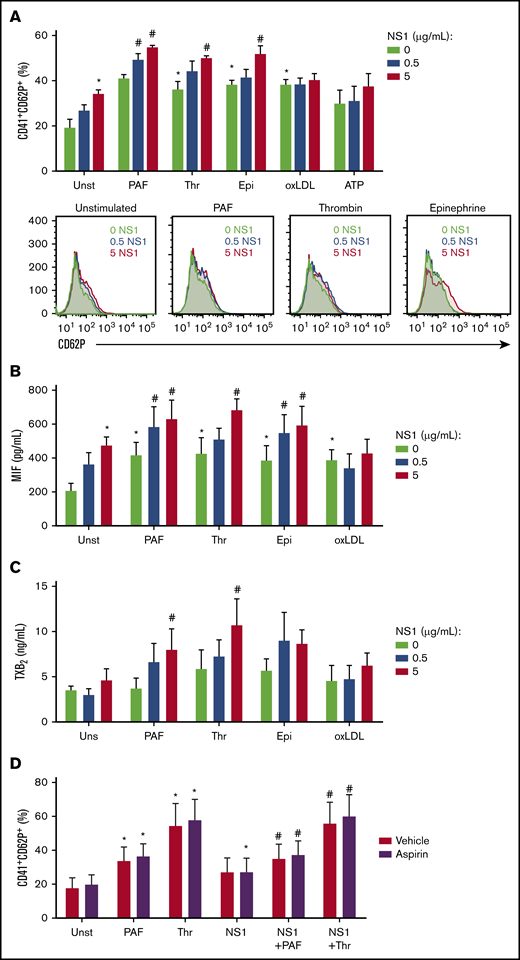

Preexposure to NS1 amplifies platelet activation by suboptimal concentrations of procoagulant agonists. Platelets were stimulated with NS1 (0, 0.5, or 5 µg/mL) produced in SF9 cells for 2.5 hours and restimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL), PAF (40 nM), oxLDL (5 µg/mL), epinephrine (10 µM), or ATP (2mM) for 30 minutes. (A) The percentage of platelets expressing surface P-selectin (CD62P); and the concentrations of MIF (B) and TXB2 (C) in platelet supernatants were evaluated. (D) Platelets were pretreated for 30 minutes with aspirin (100 μM) or vehicle, stimulated for 2.5 hours with 5 µg/mL of NS1 produced in SF9 cells, and restimulated for 30 minutes with thrombin (0.05 U/mL) or PAF (40 nM). The percentage of platelets expressing surface P-selectin was evaluated. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with unstimulated platelets; #P < .05 compared with procoagulant agonists or NS1 alone.

Preexposure to NS1 amplifies platelet activation by suboptimal concentrations of procoagulant agonists. Platelets were stimulated with NS1 (0, 0.5, or 5 µg/mL) produced in SF9 cells for 2.5 hours and restimulated with thrombin (0.05 U/mL), PAF (40 nM), oxLDL (5 µg/mL), epinephrine (10 µM), or ATP (2mM) for 30 minutes. (A) The percentage of platelets expressing surface P-selectin (CD62P); and the concentrations of MIF (B) and TXB2 (C) in platelet supernatants were evaluated. (D) Platelets were pretreated for 30 minutes with aspirin (100 μM) or vehicle, stimulated for 2.5 hours with 5 µg/mL of NS1 produced in SF9 cells, and restimulated for 30 minutes with thrombin (0.05 U/mL) or PAF (40 nM). The percentage of platelets expressing surface P-selectin was evaluated. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 5 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with unstimulated platelets; #P < .05 compared with procoagulant agonists or NS1 alone.

To inquire whether DENV NS1 also activates pathways associated with platelet procoagulant responses, we measured thromboxane B2 (TXB2), a stable metabolite from the prothrombotic eicosanoid TXA2. Treatment with NS1 alone did not induce platelet production of TXA2, but preexposure to NS1 increased TXA2 secretion by PAF- or thrombin-activated platelets (Figure 4C). We then investigated whether TXA2 secretion mediates the synergistic action of NS1 with classic agonists. However, treatment with aspirin did not affect platelet activation after NS1 plus thrombin or PAF stimulation, excluding the participation of TXA2 in this synergistic response. Altogether, these results demonstrate that DENV NS1 potentiates thromboinflammatory responses to classic agonists, increasing platelet secretion of granule-stored factors and TXA2 synthesis.

NS1 activates platelets partially depending on TLR4

It has already been demonstrated that DENV NS1 activates TLR4 on endothelial cells and leukocytes.38 Recently, insect cell–derived NS1 was shown to activate platelet TLR4.25 We therefore investigated whether NS1 from mammalian cells interacts with TLR4 on platelets. We performed a competition assay in which platelets were labeled with fluorescent LPS in the presence of increasing concentrations of mammalian cell–derived NS1. The competition assay showed a decrease in fluorescent LPS binding to platelets incubated with higher concentrations of NS1 (Figure 5A). Similar results were observed in the competition between fluorescent LPS and unlabeled LPS, used as the positive control (Figure 5B). These results demonstrate that DENV NS1 competes with LPS, indicating a strong affinity for TLR4 on platelets.

DENV2 NS1 binds and activates TLR4 on platelets. (A-B) Platelets from healthy donors were labeled with FITC-conjugated LPS (LPS-FITC, 5 or 10 µg/mL) for 5 minutes in the presence of NS1 produced by HEK cells (0, 0.5, 5 and 50 μg/mL) (A), or unlabeled LPS (0, 0.1, 1, and 10 µg/mL) (B). Each dot represents the fluorescence (mean fluorescence intensity; [MFI]) of LPS-FITC–labeled platelets. Nonlinear regression was traced according to the distribution of the dots. (C-G) Platelets were incubated with neutralizing antibodies against TLR4 (C-D), TLR2 (E), TLR6 (F), or TLR6-binding peptide (G; TLR6-BP) for 30 minutes, and stimulated with NS1 produced in HEK cells (5 µg/mL) or LPS (10 µg/mL) for 3 hours. (H) Platelets from healthy volunteers were stimulated with NS1 produced in HEK cells (5 µg/mL) or LPS (10 µg/mL) for 3 hours in the presence or absence of 10% autologous human serum. (I) Platelets resuspended in medium containing 10% human serum were incubated with neutralizing antibodies against TLR4/MD2 complex for 30 minutes and stimulated with NS1 produced in HEK cells (5 µg/mL) or LPS (10 µg/mL) for 3 hours. The percentage of platelets expressing surface P-selectin (CD62P) was evaluated in each condition. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 to 6 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with unstimulated platelets; #P < .05 compared with isotype-matched IgG.

DENV2 NS1 binds and activates TLR4 on platelets. (A-B) Platelets from healthy donors were labeled with FITC-conjugated LPS (LPS-FITC, 5 or 10 µg/mL) for 5 minutes in the presence of NS1 produced by HEK cells (0, 0.5, 5 and 50 μg/mL) (A), or unlabeled LPS (0, 0.1, 1, and 10 µg/mL) (B). Each dot represents the fluorescence (mean fluorescence intensity; [MFI]) of LPS-FITC–labeled platelets. Nonlinear regression was traced according to the distribution of the dots. (C-G) Platelets were incubated with neutralizing antibodies against TLR4 (C-D), TLR2 (E), TLR6 (F), or TLR6-binding peptide (G; TLR6-BP) for 30 minutes, and stimulated with NS1 produced in HEK cells (5 µg/mL) or LPS (10 µg/mL) for 3 hours. (H) Platelets from healthy volunteers were stimulated with NS1 produced in HEK cells (5 µg/mL) or LPS (10 µg/mL) for 3 hours in the presence or absence of 10% autologous human serum. (I) Platelets resuspended in medium containing 10% human serum were incubated with neutralizing antibodies against TLR4/MD2 complex for 30 minutes and stimulated with NS1 produced in HEK cells (5 µg/mL) or LPS (10 µg/mL) for 3 hours. The percentage of platelets expressing surface P-selectin (CD62P) was evaluated in each condition. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 to 6 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with unstimulated platelets; #P < .05 compared with isotype-matched IgG.

We then investigated whether NS1 from mammalian cells activates platelets through TLR4 engagement. Blocking TLR4 with neutralizing antibodies partially reduced NS1-induced platelet activation when compared with isotype-matched IgG (Figure 5C). As expected, LPS-induced platelet activation was totally prevented by the same concentration of anti-TLR4 (Figure 5D). The partial inhibition achieved by blocking TLR4 on NS1-activated platelets suggests that NS1 activates additional receptors. It has been demonstrated that DENV NS1 activates leukocytes through TLR2/6 heterodimers.39 We then investigated whether TLR2 and/or TLR6 participates in NS1-induced platelet activation. Neither TLR2 nor TLR6 neutralizing antibodies or TLR6 blocking peptide prevented NS1 from activating platelets (Figure 5E-G). Platelet TLR4 activation by LPS is amplified in the presence of serum factors, such as sCD14 and MD2.31,34,40,41 Similarly, platelet stimulation with NS1 in the presence of autologous serum significantly increased NS1-induced platelet activation (Figure 5H), suggesting the participation of serum factors. We then used antibodies against TLR4/MD2 complex, which inhibits LPS-induced platelet activation.40 Similar to anti-TLR4 (Figure 5C), anti-TLR4/MD2 partially inhibited NS1-induced platelet activation (Figure 5I). Altogether, these results indicate that NS1 binds and activates platelet TLR4, which is partially responsible for NS1-induced activation.

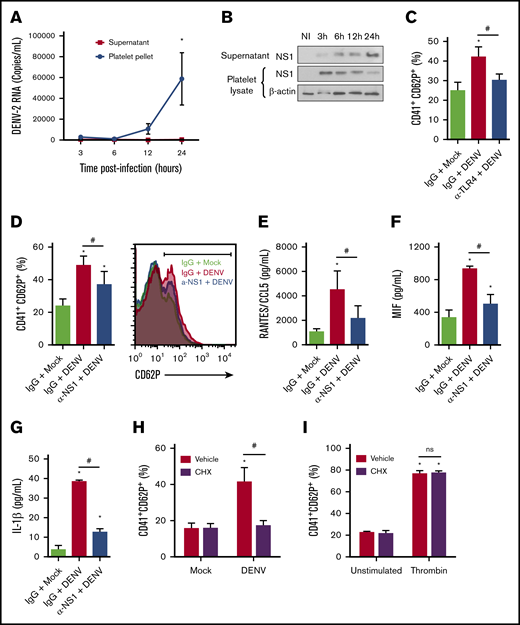

DENV-infected platelets are activated through an NS1 autocrine loop

DENV-infected platelets can replicate the DENV genome and translate it into proteins.17,18 However, even though DENV RNA and NS1 accumulate in infected platelets over time, infectious viral particles do not,17,18 suggesting that platelets sustain an abortive DENV infection. We hypothesized that viral genome translation with secretion of NS1 stimulates infected platelets autocrinally. To avoid platelet activation by exogenous NS1 in DENV-containing mosquito cell supernatants, we purified DENV particles through a sucrose gradient (supplemental Figure 1). Similar to previous reports,17,18 our data demonstrate a significant increase in DENV-2 RNA replication and NS1 protein synthesis in infected platelets over 24 hours of infection (Figure 6A-B). However, we did not detect any increase in viral RNA in supernatants from infected platelets (Figure 6A), confirming that platelets abortively replicate the virus. Although DENV-infected platelets do not release viral progeny, DENV NS1 was released in platelet supernatants over time, indicating NS1 synthesis and secretion by DENV-infected platelets (Figure 6B; supplemental Figure 4).

DENV activates platelets through an NS1 autocrine loop. (A-B) Platelets from healthy donors were infected with DENV-2 (MOI = 1). At 1.5 hours after infection, unbound viruses were washed out, and after 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours postinfectious platelet pellets and supernatants were collected for quantification of viral RNA (A) and analysis of NS1 synthesis and secretion (B). β-Actin was used as the loading control. (C-G) Platelets were infected with DENV-2 (MOI = 1) in the presence of anti-TLR4 (C) or anti-NS1 (D-G) neutralizing antibodies or isotype-matched IgG. (C-D) The percentage of platelets expressing surface P-selectin (CD62P), and the concentrations of RANTES/CCL5 (E), MIF (F), and IL-1β (G) were quantified at 6 hours after infection. (H-I) The percentage of P-selectin surface expression on platelets pretreated with cycloheximide (10 µM, 30 minutes) and infected with DENV (MOI = 1) (H) or thrombin (0.5 U/mL) (I) for 6 hours. Dots or bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 to 4 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with mock; #P < .05 between selected groups.

DENV activates platelets through an NS1 autocrine loop. (A-B) Platelets from healthy donors were infected with DENV-2 (MOI = 1). At 1.5 hours after infection, unbound viruses were washed out, and after 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours postinfectious platelet pellets and supernatants were collected for quantification of viral RNA (A) and analysis of NS1 synthesis and secretion (B). β-Actin was used as the loading control. (C-G) Platelets were infected with DENV-2 (MOI = 1) in the presence of anti-TLR4 (C) or anti-NS1 (D-G) neutralizing antibodies or isotype-matched IgG. (C-D) The percentage of platelets expressing surface P-selectin (CD62P), and the concentrations of RANTES/CCL5 (E), MIF (F), and IL-1β (G) were quantified at 6 hours after infection. (H-I) The percentage of P-selectin surface expression on platelets pretreated with cycloheximide (10 µM, 30 minutes) and infected with DENV (MOI = 1) (H) or thrombin (0.5 U/mL) (I) for 6 hours. Dots or bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 to 4 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with mock; #P < .05 between selected groups.

Attempting to evaluate whether NS1 released by infected platelets participates in DENV-induced platelet activation, we infected platelets with purified DENV2 in the presence of anti-TLR4 or anti-NS1 neutralizing antibodies. TLR4 or NS1 blocking partially reduced P-selectin surface translocation, indicating that NS1-TLR4 engagement amplifies the activation of infected platelets (Figure 6C-D). Similarly, blocking of secreted NS1 partially prevented infected platelets of secreting RANTES/CCL5, MIF, and IL-1β (Figure 6E-G). To confirm that activation of DENV-infected platelets depends on viral genome translation and release of newly synthesized NS1, we infected platelets in the presence of the translational inhibitor cycloheximide. Translational inhibition completely prevented platelet activation by DENV infection, but not thrombin stimulation (Figure 6H-I). Altogether, these results demonstrate that DENV2 abortively infects human platelets and increases platelet activation through an NS1-TLR4 autocrine loop.

Discussion

Recent evidence has implicated NS1 as a major player in dengue pathogenesis. In patients with dengue, higher levels of NS1 associate with severe dengue syndrome.21,42 Beyond being a direct correlate of viral replication, secreted NS1 contributes to dengue pathogenesis by modulating the immune response.43,44 NS1-induced activation of leukocytes and endothelial cells amplifies inflammation and vascular dysfunction.24,38,39,42,45 Observations from in vitro–stimulated endothelial cells and intradermally injected mice have evidenced NS1-induced endothelial dysfunction through mechanisms that are both dependent on and independent of cytokines.24,42,45 NS1 has been shown to induce synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines in leukocytes38,39,46 and to increase DENV replication in dendritic cells.46 We extended the evidence that DENV NS1 activates platelets25 by identifying and analyzing key thromboinflammatory responses in platelets exposed to DENV or NS1. We defined a novel NS1-dependent autocrine signaling mechanism by which DENV genome translation, NS1 secretion, and TLR4 engagement participate in platelet activation and amplify the secretion of proinflammatory mediators.

A recent study reported that insect cell–derived NS1 activates platelets in vitro, increasing aggregation and adhesion.25 In that study, NS1 depletion from DENV inoculum significantly reduced hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia in infected mice.25 Even though NS1 from insect cells inoculated into the skin alongside the virus is unlikely to contact and activate platelets in the circulation, it has been proposed that the presence of NS1 in the inoculum enhances DENV spreading and systemic infection.25,44,47 In mosquitoes, NS1 acquired in a blood meal enhances DENV infection by promoting barrier disfunction in the midgut.47 Similarly, NS1 in mosquito saliva may break dermal endothelial barrier integrity, thus increasing DENV spreading and replication in mammal hosts.44,48 Consistently, immunodepletion of NS1 from DENV inoculum reduces host-derived NS1 antigenemia.25 Anti-NS1 antibodies generated by NS1 vaccination also reduce viremia in a subsequent DENV challenge.47 Thus, insect-derived NS1 may lead to increased viremia, NS1 antigenemia, and pathophysiological host responses. In this scenario, higher levels of both DENV and NS1 may contribute to platelet activation and platelet-mediated thromboinflammatory responses, as platelets can be activated by DENV and NS1, independently, as we demonstrated in this study.

We and others have shown increased platelet activation by DENV in vitro.9-11,18,49,50 Using purified virus, we now confirm DENV-induced platelet activation in the absence of exogenous NS1. Although recent studies have identified the mechanisms of DENV binding and viral protein synthesis in platelets,17,18 it has remained unknown whether DENV genome translation is essential for DENV-induced platelet activation. We now show that activation of infected platelets involves translation and secretion of NS1. However, blocking secreted NS1 only partially inhibited platelet activation, indicating the existence of additional activating signals. These additional mechanisms may also require viral genome translation, since translational inhibition completely blocked DENV-induced platelet activation. In agreement, DENV genome copies in platelets correlate positively with platelet activation in acute dengue infection.49 A possible mechanism is the recognition of viral RNA by TLR3 or TLR7, which have already been reported in platelets.51-53 Even though infected platelets translated and replicated the viral genome, they did not release mature viral particles, as evidenced in this and other reports.17,18 However, we now demonstrate that infected platelets secrete newly synthesized NS1, contributing to platelet activation and inflammatory amplification. We further postulate that platelet-derived NS1 activates other immune and vascular cells in dengue.

When compared with DENV infection, NS1 stimulation induces a partial inflammatory phenotype in platelets. Similar to infected platelets, NS1-stimulated platelets release the stored factors PF4, RANTES, and MIF but, in contrast, they do not secrete IL-1β. As in nucleated cells, platelet secretion of IL-1β requires the activation of inflammasome complexes.11,54-57 As previously shown,11 DENV infection provides all signals for pro-IL-1β synthesis and secretion in platelets. Considering that other TLR4 agonists, such as LPS, can induce platelet synthesis of IL-1β,34,57,58 we hypothesized that NS1 induces pro-IL1β synthesis and a second signal may promote its secretion. As proof of principle, costimulation with ATP, a classic trigger of NLRP3-inflammasome, induced IL-1β secretion by NS1-activated platelets. Even though NS1 alone did not induce IL-1β secretion, we concluded that it is a major trigger of IL-1β synthesis in DENV-infected platelets, because NS1 neutralization almost completely blocked DENV-induced IL-1β release. IL-1β and MIF, proinflammatory cytokines synthesized and secreted by NS1-activated platelets, are associated with increased vascular permeability,6,8,11,59 coagulopathy,60,61 and mortality8,62 in dengue.

Considering that multiple inflammatory signals coexist during dengue infection in humans, the synergism between NS1 and classic platelet agonists may be of particular importance. We provide evidence that preexposure to NS1 enhances platelet activation by thrombin, PAF, and epinephrine. Similarly, NS1 was recently reported to enhance platelet aggregation by a subthreshold concentration of adenosine diphosphate.25 Of note, the agonists that synergized with NS1 by increasing α-granule release in our experiments were those that activate G protein–coupled receptors. TXA2 synthesis was also induced by the synergistic action of NS1 with thrombin and PAF, but the release of TXA2 was not necessary for the amplification of α-granule release in this model. Patients with dengue present evidence of increased thrombin generation.60,63-66 Analysis of infected patients, together with in vitro and in vivo experiments, have also evidenced increased production of PAF in dengue.67-70 As observed with NS1, increased PAF and thrombin generation are associated with severe dengue syndrome.21,42,64,65,67 We therefore propose that the thromboinflammatory phenotype in platelets from patients with dengue involves a complex set of signals including DENV infection, NS1-TLR4 engagement, and activation by classic prothrombotic agonists.

It is well established that TLR4 participates in recognition and response to NS1 in immune and endothelial cells.24,25,38,71 A previous publication also reported that NS1 induces leukocyte activation though TLR2/6,39 but this finding remains controversial.38,71 In our experiments, NS1-induced platelet activation was partially dependent on TLR4, but did not involve TLR2/6. Another group has also observed a partial effect of TLR4 inhibition on NS1-induced platelet activation.25 Altogether, these studies indicate that NS1 can activate cellular responses through other receptors beyond TLR4 that remain to be identified. Consistently, TLR4-knockout mice were not protected from a local increase in vascular permeability after intradermal NS1 injection,45 even though treatment with a TLR4 antagonist prevented plasma leakage in DENV-infected mice in another study.38 The latter raises the possibility that other TLR4 agonists participate in dengue pathogenesis, among which circulating cell-free histones9 and LPS from microbial translocation72 have already been reported. Additional studies are needed to further elucidate the role of TLR4 in systemic NS1 endotoxemia.

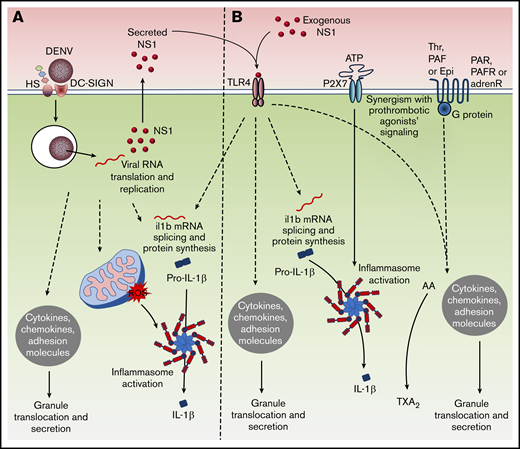

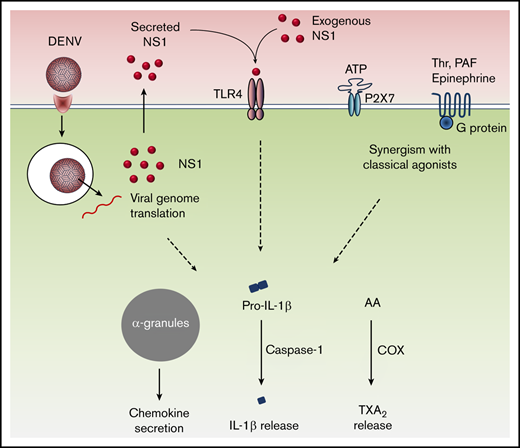

In summary, we describe new mechanisms of platelet activation by DENV involving platelet infection, translation, and secretion of the viral toxin NS1 (Figure 7). DENV-infected platelets support an abortive viral infection, in that they translate and replicate the viral genome but do not release viral replicates. Platelets respond to the infection by translocating and secreting stored factors and also synthesizing IL-1β, which is released through caspase-1–mediated processing. All those infection-driven responses are amplified by a secreted NS1 autocrine loop (Figure 7A). Platelets also respond to exogenous NS1 through TLR4 signaling, leading to granule translocation and IL-1β synthesis, but not inflammasome–mediated IL-1β secretion, which can be achieved by a second signal, such as ATP (Figure 7B). Finally, NS1 synergizes with classic platelet agonists enhancing prothrombotic and proinflammatory platelet responses (Figure 7B). These data provide an integrated view of platelet responses to pathogen- and host-derived agonists. All these cellular events are potentially involved in platelet-mediated inflammation and cytokine-induced pathogenesis in dengue.

Schematic of inflammatory signaling in platelets upon DENV infection and NS1 stimulation. (A) DENV infection activates platelets inducing the translocation of granule-stored factors, pro-IL-1β synthesis, and inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion. Platelets support viral genome replication and translation, releasing NS1 to the extracellular space. Secreted NS1 amplifies degranulation and IL-1β synthesis in infected platelets through an autocrine loop. (B) Exogenous NS1 activates platelets through TLR4, leading to translocation and release of stored factors, and to pro-IL-1β synthesis. Synergism with procoagulant agonists potentiates NS1-induced platelet activation, increasing granule secretion (thrombin, PAF, or epinephrine), inducing the synthesis of TXA2 (thrombin or PAF), or activating inflammasome to trigger IL-1β processing and release (ATP).

Schematic of inflammatory signaling in platelets upon DENV infection and NS1 stimulation. (A) DENV infection activates platelets inducing the translocation of granule-stored factors, pro-IL-1β synthesis, and inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion. Platelets support viral genome replication and translation, releasing NS1 to the extracellular space. Secreted NS1 amplifies degranulation and IL-1β synthesis in infected platelets through an autocrine loop. (B) Exogenous NS1 activates platelets through TLR4, leading to translocation and release of stored factors, and to pro-IL-1β synthesis. Synergism with procoagulant agonists potentiates NS1-induced platelet activation, increasing granule secretion (thrombin, PAF, or epinephrine), inducing the synthesis of TXA2 (thrombin or PAF), or activating inflammasome to trigger IL-1β processing and release (ATP).

For original data, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Guy A. Zimmerman and Matthew T. Rondina for critical review of the manuscript; the multiuser facility in Flow Cytometry at the Jose Henrique Bruschi experimental campus; Embrapa Gado de Leite and Wanessa Araújo Carvalho for technical assistance; and the Laboratório Integrado de Pesquisa (LIP) from the Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências Biológicas (PPGCBio/UFJF) multiuser platform.

This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa fo Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (E.D.H.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.C.Q.-T. performed most of the experiments, data analyses, and manuscript drafting; S.V.R. performed part of the experiments and data analyses; G.B.-L performed viral propagation, DENV genome quantification, and data analyses; D.R.C. and P.H.C. performed E coli and SF9 cell transformation and NS1 expression and purification; R.M.-B. designed the experiments and reviewed the manuscript; P.T.B. designed the experiments and reviewed the manuscript; and E.D.H. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and directed all aspects of the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Eugenio D. Hottz, Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Institute of Biological Sciences, Department of Biochemistry, Rua José Lourenço Kelmer, São Pedro, Juiz de Fora 36036-900, Brazil; e-mail: eugenio.hottz@icb.ufjf.br.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![DENV2 NS1 binds and activates TLR4 on platelets. (A-B) Platelets from healthy donors were labeled with FITC-conjugated LPS (LPS-FITC, 5 or 10 µg/mL) for 5 minutes in the presence of NS1 produced by HEK cells (0, 0.5, 5 and 50 μg/mL) (A), or unlabeled LPS (0, 0.1, 1, and 10 µg/mL) (B). Each dot represents the fluorescence (mean fluorescence intensity; [MFI]) of LPS-FITC–labeled platelets. Nonlinear regression was traced according to the distribution of the dots. (C-G) Platelets were incubated with neutralizing antibodies against TLR4 (C-D), TLR2 (E), TLR6 (F), or TLR6-binding peptide (G; TLR6-BP) for 30 minutes, and stimulated with NS1 produced in HEK cells (5 µg/mL) or LPS (10 µg/mL) for 3 hours. (H) Platelets from healthy volunteers were stimulated with NS1 produced in HEK cells (5 µg/mL) or LPS (10 µg/mL) for 3 hours in the presence or absence of 10% autologous human serum. (I) Platelets resuspended in medium containing 10% human serum were incubated with neutralizing antibodies against TLR4/MD2 complex for 30 minutes and stimulated with NS1 produced in HEK cells (5 µg/mL) or LPS (10 µg/mL) for 3 hours. The percentage of platelets expressing surface P-selectin (CD62P) was evaluated in each condition. Bars represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 to 6 independent experiments. *P < .05 compared with unstimulated platelets; #P < .05 compared with isotype-matched IgG.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/4/9/10.1182_bloodadvances.2019001169/1/m_advancesadv2019001169f5.png?Expires=1769085440&Signature=EYkkHgfAADMJeBwJIp5AC5gDxQi3ZR3dTXTnHs1SeqGi9-oSD84VfxQGDX3vP1wfqmlxOVtp1sk2Tc0cEQHplN6aVNLuT2jauBmAhsbDnIUqYTfnRzjtnBdHG8KWZttktBuYx5fYEfmbnMyAn4ZKmPJD2Hz6zH-o-fx83VE2AI707y2kTdpjOVszB8nDIgWCO5iGWrJ2L8M6xiMKzpNm44Qi08XDSxUBmJMH4usoBV3wzXvysAPBI2dK3pSxPRyNHPtX9z6DADUdpN7p49tae~G6Tr863CsJd8ld696pIZMAwzldIpb0~giVgphpU5YlhQx8kf-BD5xYzaKwYbglsw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)