Key Points

In patients with relapsed DLBCL who undergo ASCT, EFS declines with each year at least until the fourth year of follow-up.

The SMR in DLBCL post-ASCT is significantly higher at least until 5 years of EFS.

Abstract

The conditional survival of patients after frontline therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) approaches that of the general population once patients have survived disease free for 2 years. We sought to determine the conditional survival of patients among patients with relapsed de novo DLBCL successfully undergoing an autologous stem-cell transplant (ASCT) after first relapse. A total of 478 patients with de novo DLBCL, relapsed after 1 treatment from the Collaborative Trial in Relapsed Aggressive Lymphoma (CORAL) and LY.12, were included. Patients were followed prospectively after ASCT for a median of 5.3 and 8.2 years, respectively. Individual patient data were analyzed for event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival. Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) were estimated using French and Canadian life tables. The EFS estimates declined with each year of follow-up after ASCT and were 50.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 43.7% to 56.3%) and 43.4% (95% CI: 36.7% to 49.9%) at 5 years in CORAL and LY.12, respectively. The rate of death stabilized once patients achieved at least 4 years of EFS. Compared with the age- and sex-matched population, the SMR was significantly higher until 5 years after ASCT, when values were no longer statistically significant. Patients undergoing ASCT for relapsed DLBCL continue to have a higher rate of death at least until they have survived event free for 5 years. These observations can help to determine endpoints for future clinical trials in this population and for patient counseling. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00078949.

Introduction

The current standard-of-care therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) plus an anthracycline-based chemotherapy, is associated with complete remission in the majority of patients.1,2 Moreover, patients who achieve an event-free survival of 24 months (EFS24) from the time of diagnosis may have an overall survival (OS) that is equivalent or close to equivalent to the general population.3,4

However, 30% to 40% of patients are refractory to initial treatment or relapse after initial response to chemoimmunotherapy.1,2 For patients who experience disease progression, the main potential curative option remains the combination of high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT).5,6 Several retrospective studies have examined the question of conditional survival (the probability of surviving further given that the patient has already survived a specific number of years) following ASCT for relapsed DLBCL. In general, these studies indicate that at 2 years, patients undergoing an ASCT for relapsed or refractory DLBCL have an excess death rate when compared with the general population, and this is largely driven by lymphoma relapse early on in follow-up.7 Some studies have shown that conditional survival may approach that of the general population if the patient has survived 5 to 10 years post-ASCT,8-10 whereas others indicate that even 30 years from the time of ASCT there remains an excess mortality risk.11,12 These studies are limited by their retrospective nature, inclusion of multiple disease entities, treatment with ASCT after a varying number of relapses, and inclusion of patients not treated with rituximab.

The LY.12 and Collaborative Trial in Relapsed Aggressive Lymphoma (CORAL) phase 3 randomized studies examined the choice of salvage regimens for the treatment of DLBCL after frontline treatment failure and the value of rituximab maintenance posttransplant. Using the prospectively collected, individual patient data from LY.12 and CORAL, we sought to determine the value of EFS as a surrogate endpoint for OS among patients with relapsed and refractory DLBCL undergoing ASCT.

Methods

Data sources and patient inclusion

Individual patient data from the Canadian Cancer Trials group LY.12 and the CORAL studies were used for this analysis. The Canadian Cancer Trials group LY.12 study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov, #NCT00078949, and was conducted mainly in Canada but also with participating centers in the United States, Australia, and Italy. This trial was designed to compare the efficacy of gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin to dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin as salvage chemotherapy prior to ASCT. Patients were enrolled from August 2003 to November 2011. Follow-up data were updated to June 30, 2017, thus providing a median follow-up of 8.2 years. Rituximab was added to this salvage regimen as of November 2005. Patients 18 years or older with aggressive-histology lymphoma who had at least 1 anthracycline-based regimen were included. They were stratified by treating center, international prognostic index (IPI), risk factors at trial entry, response to primary therapy, and previous rituximab treatment. For patients who received ASCT, chest, abdomen, and pelvic computed tomography scans were obligatory at 3, 7, 12, and 24 months for CORAL and 3, 7, 13, and 25 months for LY.12. Thereafter, computed tomography scans were recommended annually for CORAL, and patients were followed clinically at least for 5 years. Data linkage with administrative sources was performed to obtain information of disease status and vital status in LY.12.

The CORAL study was a multicenter randomized trial based in France but which included 12 other countries (European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials number 2004-002203-32 and clinicaltrials.gov #NCT00137995). The trial enrolled patients from July 2003 to September 2007 and compared the efficacy of rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide to rituximab–dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin. Patients between the ages of 18 and 65 who had aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) treated with prior anthracycline-based therapy were included. They were stratified by participating country, prior rituximab, and timing of relapse from prior treatment. After ASCT, patients were followed at 3, 5, 9, 11, 12 months, then every 6 months for 2 years, and then annually. Both CORAL and LY.12 randomly assigned patients after ASCT to either rituximab maintenance 375 mg/m2 every 8 weeks for 1 year or to observation.

We included patients enrolled in both the LY.12 and CORAL studies who had histology of de novo DLBCL at diagnosis, who had received 1 prior line of therapy only, and who had completed salvage chemotherapy and ASCT; those patients with transformed follicular lymphoma were excluded. Informed consent for participation in CORAL and LY.12 was obtained from all patients according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical methodology

EFS was defined as time from ASCT until disease relapse or progression, initiation of new lymphoma therapy, or death from any cause. EFS indicators at specific time points were defined as EFS status at that time point from date of ASCT. OS was defined as the time from ASCT until death from any cause. The survival curves of patients at different EFS time points (12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months) were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The competing risk model was used to calculate the 5-year cumulative incidence of death from lymphoma.

Survival curves for the general population were derived from the Canadian (Statistics Canada, http://www.statcan.gc.ca) and French (Insee, https://www.insee.fr) life tables and were used to compare mortality rate with patients from LY.12 and CORAL, respectively. Standardized mortality rate (SMR), the ratio of observed to the expected mortality, was calculated annually from patients completing transplant (EFS0) to EFS60. A multivariate analysis was performed to correlate survival with age at ASCT, IPI score at time of salvage chemotherapy, response to prior therapy, and disease status after salvage chemotherapy at 2 and 5 years. SAS version 9.3 was used for baseline patient characteristics, survival analyses, and multivariable analysis. R version 3.5.1 was used for the SMR calculation.

Results

Of the 619 patients enrolled in LY.12, 221 with de novo DLBCL proceeded to ASCT and were eligible for this analysis. Similarly, 257 of 481 patients enrolled in CORAL underwent ASCT and were included here. Data were updated until 2017 for LY.12 and until 2015 for CORAL, for a median follow-up time of 8.2 and 5.3 years (by reverse Kaplan-Meier estimate), respectively. Table 1 provides the baseline patient characteristics. The mean age for these cohorts was 51 years and 54 years. Most patients were male (65% and 62%); 9% and 17% had primary refractory disease, and 53% and 56% had received rituximab during initial and salvage therapy, in CORAL and LY.12, respectively. Overall, the populations were comparable with regard to disease severity as measured by IPI and stage at time of salvage chemotherapy. Patients in CORAL had a higher overall response rate.

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics

| Demographic or characteristic . | CORAL (n = 257) . | LY.12 (n = 221) . | Total (N = 478) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range), y | 51 (19-66) | 54 (25-71) | 53 (19-71) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 91 (35) | 84 (38) | 175 (37) |

| Male | 166 (65) | 137 (62) | 303 (63) |

| IPI score* | |||

| 0 to 1 | 125 (50) | 98 (44) | 223 (47) |

| 2 | 73 (29) | 72 (33) | 145 (31) |

| ≥3 | 52 (21) | 51 (23) | 103 (22) |

| Disease stage | |||

| I | 43 (17) | 21 (10) | 64 (13) |

| II | 64 (25) | 64 (29) | 128 (27) |

| III | 43 (17) | 55 (25) | 98 (21) |

| IV | 105 (41) | 81 (36) | 186 (39) |

| LDH > upper limit of normal | 111 (44) | 99 (45) | 210 (44) |

| Rituximab included in initial and salvage therapy | 135 (53) | 123 (56) | 258 (54) |

| Stage ≥3 | 150 (58) | 136 (62) | 285 (60) |

| Prior radiotherapy | 74 (29) | 54 (24) | 128 (27) |

| B symptoms | 48 (19) | 58 (27) | 106 (23) |

| Response to first line therapy | |||

| CR, CRu, PR | 233 (91) | 184 (83) | 417 (87) |

| PD, SD | 24 (9) | 37 (17) | 61 (13) |

| Demographic or characteristic . | CORAL (n = 257) . | LY.12 (n = 221) . | Total (N = 478) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range), y | 51 (19-66) | 54 (25-71) | 53 (19-71) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 91 (35) | 84 (38) | 175 (37) |

| Male | 166 (65) | 137 (62) | 303 (63) |

| IPI score* | |||

| 0 to 1 | 125 (50) | 98 (44) | 223 (47) |

| 2 | 73 (29) | 72 (33) | 145 (31) |

| ≥3 | 52 (21) | 51 (23) | 103 (22) |

| Disease stage | |||

| I | 43 (17) | 21 (10) | 64 (13) |

| II | 64 (25) | 64 (29) | 128 (27) |

| III | 43 (17) | 55 (25) | 98 (21) |

| IV | 105 (41) | 81 (36) | 186 (39) |

| LDH > upper limit of normal | 111 (44) | 99 (45) | 210 (44) |

| Rituximab included in initial and salvage therapy | 135 (53) | 123 (56) | 258 (54) |

| Stage ≥3 | 150 (58) | 136 (62) | 285 (60) |

| Prior radiotherapy | 74 (29) | 54 (24) | 128 (27) |

| B symptoms | 48 (19) | 58 (27) | 106 (23) |

| Response to first line therapy | |||

| CR, CRu, PR | 233 (91) | 184 (83) | 417 (87) |

| PD, SD | 24 (9) | 37 (17) | 61 (13) |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

CR, complete remission; Cru, complete remission unconfirmed; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease.

IPI was determined at time of salvage chemotherapy.

As shown in Table 2, EFS declines with each year of follow-up until 5 years, with the largest declines in EFS occurring during the first 2 years of follow-up. At 12 months, 65.5% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 59.2, 71.0%) and 61.5% (95% CI: 54.8, 67.6%) of patients are alive and event free in CORAL and LY.12, respectively. By 5 years, the EFS is 50.1% (95% CI: 43.7, 56.3%) and 43.4% (95% CI: 36.7, 49.9%) for CORAL and LY.12, respectively. There were 3 deaths within 30 days of ASCT for each of the studies.

EFS

| EFS, mo . | CORAL (n = 257) . | LY.12 (n = 221) . |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 166 (65.5) [59.2, 71.0] | 136 (61.5) [54.8, 67.6] |

| 24 | 143 (57.8) [51.4, 63.6] | 121 (54.8) [47.9, 61.0] |

| 36 | 127 (53.3) [46.9, 59.3] | 113 (51.1) [44.3, 57.5] |

| 48 | 114 (52.8) [46.5, 58.8] | 102 (47.9) [41.1, 54.3] |

| 60 | 86 (50.1) [43.7, 56.3] | 87 (43.4) [36.7, 49.9] |

| EFS, mo . | CORAL (n = 257) . | LY.12 (n = 221) . |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | 166 (65.5) [59.2, 71.0] | 136 (61.5) [54.8, 67.6] |

| 24 | 143 (57.8) [51.4, 63.6] | 121 (54.8) [47.9, 61.0] |

| 36 | 127 (53.3) [46.9, 59.3] | 113 (51.1) [44.3, 57.5] |

| 48 | 114 (52.8) [46.5, 58.8] | 102 (47.9) [41.1, 54.3] |

| 60 | 86 (50.1) [43.7, 56.3] | 87 (43.4) [36.7, 49.9] |

Values are n (%) [95% confidence interval].

The causes of death in both CORAL and LY.12 are dominated by lymphoma relapse particularly until EFS24 (Table 3). At this point, 60 of 71 deaths in CORAL and 73 of 81 deaths in LY.12 are due to lymphoma relapse. At EFS24, the cause of death from lymphoma approaches death from other causes, particularly among patients included in LY.12. As well, in LY.12, at EFS60 the death from other causes exceeds death from lymphoma relapse. The limited follow-up in CORAL precludes an analysis of competing risk of death at EFS60. Other causes of death include other malignancy (n = 7 in CORAL, n = 6 in LY.12), toxicity of treatment (n = 7 in CORAL, n = 3 in LY.12), concurrent illness (n = 2 in CORAL, n = 9 in LY.12), toxicity from a new treatment (n = 6 in CORAL, n = 1 in LY.12), and other reasons (n = 5 in CORAL).

Cause of death after ASCT

| . | CORAL (n = 98) . | LY.12 (n = 102) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competing risk analysis . | Death from lymphoma relapse . | Death from other cause . | Death from lymphoma relapse . | Death from other cause . |

| EFS0 | 27.3 | 10 | 34.6 | 6.5 |

| EFS24 | 11.4 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 7.7 |

| EFS60 | No data | No data | 2.6 | 4.0 |

| . | CORAL (n = 98) . | LY.12 (n = 102) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competing risk analysis . | Death from lymphoma relapse . | Death from other cause . | Death from lymphoma relapse . | Death from other cause . |

| EFS0 | 27.3 | 10 | 34.6 | 6.5 |

| EFS24 | 11.4 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 7.7 |

| EFS60 | No data | No data | 2.6 | 4.0 |

Values are percentages.

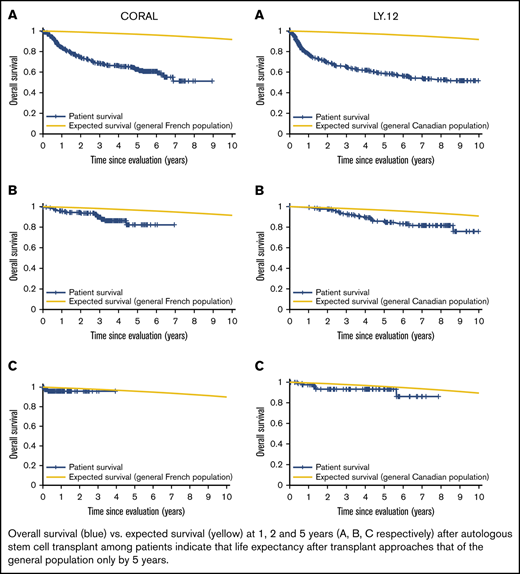

Based on the conditional survival analysis depicted in Figure 1A-B (supplemental Table 1), the rate of death diminishes with every EFS year gained following an ASCT for both CORAL and LY.12. When combining the data for these 2 studies (Figure 1C), clearly distinct 1-, 2-, and 5-year OSs are estimated for EFS years 1 and 2. However, by the fourth and fifth years of EFS, the median 1-, 2-, and 5-year OS range from 89.5% to 97%, and all CIs overlap. Before EFS24, the rate of death is greater than the period after which EFS24 is achieved. Thus, once a patient has achieved EFS48 and certainly by EFS60 in both CORAL and LY.12, the subsequent OS is >90%. This suggests stabilization in the mortality rate by these time points. The follow-up for CORAL is only 0.77 years at EFS60 but is 4.07 years in LY.12.

One-year, 2-year, and 5-year OS after specified EFS time points with shaded 95% CI area. (A) Data from the CORAL study. (B) Data from the LY.12 study. (C) Combined data from CORAL and LY.12 studies.

One-year, 2-year, and 5-year OS after specified EFS time points with shaded 95% CI area. (A) Data from the CORAL study. (B) Data from the LY.12 study. (C) Combined data from CORAL and LY.12 studies.

When compared with the age- and sex-specific rates in the general population, the SMR decreases with each additional year of EFS achieved. Despite the steady decrease, there remains significant excess death among patients with DLBCL undergoing ASCT when compared with the general population up to and including EFS48. By EFS60, there is no statistically significant difference in SMR (Table 4).

SMR for EFS achieved

| . | CORAL . | LY.12 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | SMR . | 95% CI . | SMR . | 95% CI . |

| EFS 0 | 15.2 | 12.3 to 18.6 | 12.6 | 10.3 to 15.3 |

| EFS 12 | 7.4 | 5.0 to 10.4 | 4.6 | 3.1 to 6.6 |

| EFS 24 | 5.3 | 3.1 to 8.5 | 3.6 | 2.2 to 5.6 |

| EFS 36 | 3.1 | 1.3 to 6.4 | 3.5 | 2.0 to 5.8 |

| EFS 48 | 4.9 | 2.0 to 10.1 | 3.0 | 1.5 to 5.6 |

| EFS 60 | 4.5 | 0.9 to 13.3 | 2.3 | 0.8 to 5.0 |

| . | CORAL . | LY.12 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | SMR . | 95% CI . | SMR . | 95% CI . |

| EFS 0 | 15.2 | 12.3 to 18.6 | 12.6 | 10.3 to 15.3 |

| EFS 12 | 7.4 | 5.0 to 10.4 | 4.6 | 3.1 to 6.6 |

| EFS 24 | 5.3 | 3.1 to 8.5 | 3.6 | 2.2 to 5.6 |

| EFS 36 | 3.1 | 1.3 to 6.4 | 3.5 | 2.0 to 5.8 |

| EFS 48 | 4.9 | 2.0 to 10.1 | 3.0 | 1.5 to 5.6 |

| EFS 60 | 4.5 | 0.9 to 13.3 | 2.3 | 0.8 to 5.0 |

In a subgroup analysis of patients receiving rituximab during initial and relapse therapy, a similar trend is observed for the conditional survival analysis (supplemental Table 2; supplemental Figure 1) and standardized mortality ratio (SMR) (supplemental Table 3).

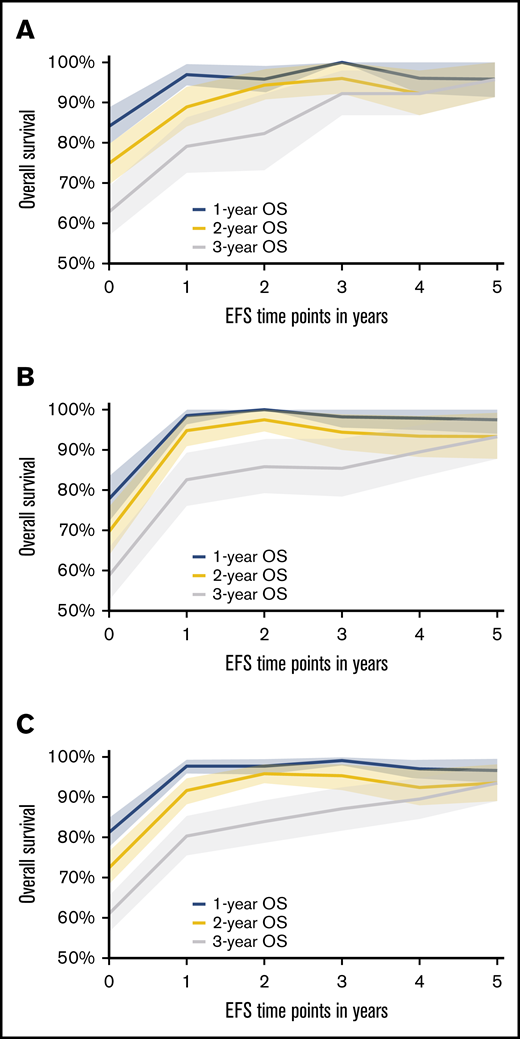

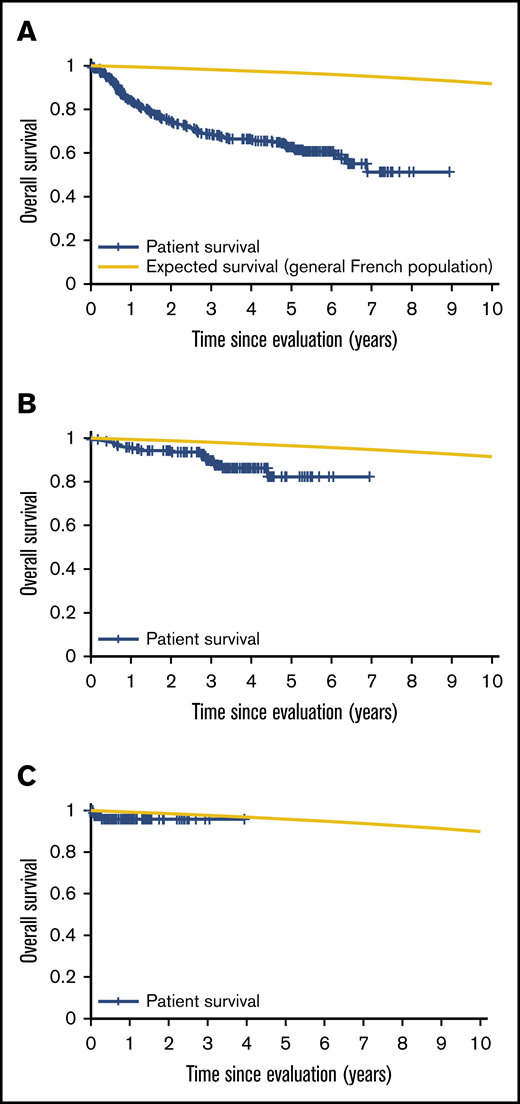

Patient mortality at EFS0, 24, 60 for both CORAL and LY.12 compared with the general population decreases over time and approaches the general population by EFS60, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, for CORAL and LY.12.

OS vs expected survival in the CORAL study post-ASCT. (A) OS immediately post-ASCT. (B) OS post-EFS24. (C) OS post-EFS60.

OS vs expected survival in the CORAL study post-ASCT. (A) OS immediately post-ASCT. (B) OS post-EFS24. (C) OS post-EFS60.

OS vs expected survival in the LY.12 study post-ASCT. (A) OS immediately post-ASCT. (B) OS post-EFS24. (C) OS post-EFS60.

OS vs expected survival in the LY.12 study post-ASCT. (A) OS immediately post-ASCT. (B) OS post-EFS24. (C) OS post-EFS60.

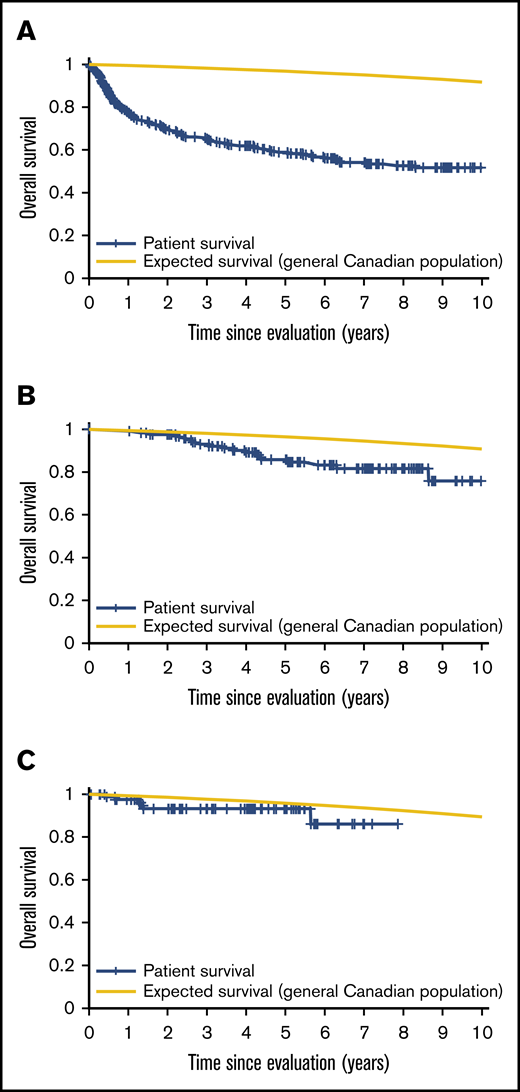

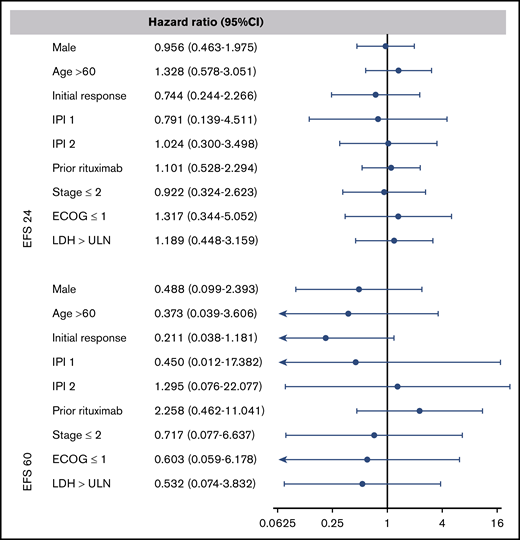

To examine the prognostic value of age at ASCT, IPI score, response to prior therapy, and disease status after salvage chemotherapy, we performed a multivariable analysis at EFS24 and EFS60. The multivariate analysis shows that these classic predictors of prognosis used at the time of diagnosis and at the time of ASCT5 no longer predict long-term outcome once EFS24 or EFS60 is achieved (Figure 4).

Forest plots of the multivariate analysis for combined CORAL and LY.12 studies. A hazard ratio of less than 1 indicates a lower risk of relapse or death after autologous transplant. ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Forest plots of the multivariate analysis for combined CORAL and LY.12 studies. A hazard ratio of less than 1 indicates a lower risk of relapse or death after autologous transplant. ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that patients with de novo DLBCL who are treated with salvage chemotherapy and undergo an ASCT after first-line therapy achieve stabilization in mortality only after surviving disease free for 5 years post-ASCT. This is in contrast to the analyses of DLBCL patients after first-line chemoimmunotherapy, where there is a high predictive value of EFS24 as a surrogate marker for OS.3,4 The striking difference in the normalization of OS between DLBCL following initial treatment and relapsed/refractory DLBCL treated with ASCT highlights the poorer prognosis of the latter group of patients and the limitations of ASCT in this disease. The cause of death in most cases was relapsed DLBCL. Interestingly, the rate of death from non–lymphoma-related causes observed here was not higher post-ASCT at EFS24 than what is reported after frontline therapy.3,4

Our findings agree with multiple prior retrospective studies that included a subgroup of patients with DLBCL treated with ASCT. These studies report that the SMR at 5 years after ASCT varies between 2.9 and 5.1.9,12 In a recent population-based study conducted in Norway assessing the survival of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma after high-dose therapy and ASCT, patients with DLBCL surviving 5 years after therapy had an SMR that was also not statistically significant at this time point (SMR 1.7; 95% CI: 0.9 to 3.1).10 However, these studies reported SMR on patients who conditionally survived 5 years following ASCT, without specifying their ongoing disease-free status and thus may have included patients who relapsed at a prior time point. Our analysis did not carry forward patients to the next time point if they had relapsed in the interim.

ASCT remains an important therapeutic option for patients with DLBCL who relapse after an R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone)-like regimen, with 33% to 39% of patients remaining alive and disease free at 5 years. The benefit of ASCT is greatest among patients with low IPI at relapse and with late relapses (occurring >1 year after first-line therapy).13 For those patients with more adverse baseline characteristics, new therapeutic options are needed. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CART) therapy has been reported to provide durable complete remission in patients with multiply relapsed DLBCL, including post-ASCT, or primary refractory disease after at least 2 lines of therapy.14-16 Long-term follow-up data are still needed to fully appreciate the benefit of CART therapy in this setting, but observations from phase 2 trials to date have reported few relapses after 1 year. Two trials, ZUMA 7 and BELINDA, that compare the CART products axicabtagene-ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel, respectively, to salvage chemotherapy and ASCT, are ongoing (clinicaltrials.gov #NCT00078949 and #NCT03570892). Both trials exclude patients with relapsed DLBCL 1 year or more after first-line therapy, for whom survival is most favorable in both LY.12 and CORAL.6,13 The data presented here may provide some context with regard to durability of response in high-risk populations of patients with relapsed and refractory DLBCL following newer treatment approaches.

Based on the multivariate analysis, we conclude that the classical variables of prognosis, such as IPI, age, and initial response to salvage chemotherapy, are no longer predictive of survival once patients have survived disease free for at least 24 months after their ASCT. One possible explanation for this could be that lymphoma as a cause of mortality decreases greatly after EFS24.

One strength and unique feature of our study compared with other analyses is the use of data gathered from 2 large randomized controlled trials with robust methodology and reporting of follow-up in order to assess the survival of patients with DLBCL who received ASCT after first relapse. Our sample size is large. However, by EFS60, due to small observed number of deaths and short follow-up in CORAL, we are unable to conclude with certainty that patients are no longer at higher risk of death compared with the general population. Another limitation of our study is that we elected to use the general population life tables of the Canadian and French populations to reflect our control mortality for the LY.12 and CORAL studies, respectively, whereas both trials enrolled patients internationally. Overall, these represented a minority of the patients in LY.12, but country of origin was more heterogeneous in CORAL.13 Overall, however, the conclusion remains the same: SMR is increased for patients with relapsed de novo DLBCL treated with ASCT at least until 5 years of follow-up in both study cohorts.

In conclusion, although SMRs for patients with DLBCL surviving event free for 2 years after ASCT decrease during subsequent years of follow-up, rates of death remain high, from lymphoma or treatment-related complications, at least up to the first 5 years after ASCT. These observations need to be considered in determining endpoints for clinical trials of new agents and approaches in this lymphoma population, and in discussing outcomes with patients referred for ASCT.

Requests for data sharing should be made to Michael Crump (michael.crump@uhn.on.ca) or Bingshu E. Chen (bechen@ctg.queensu.ca).

Authorship

Contribution: S.A. designed and conducted the study and interpreted all the results; S.L. designed and conducted the study and interpreted the results; B.E.C. designed and conducted the study; C.G., M.C., and R.M. contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of results; R.M. contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of results; P.F. contributed to the design and conduct of the study; A.H. contributed to the design of the study; and E.v.d.N., L.E.S., N.S., T.B., A.K., S.R., M.S., C.S., and M.S.D. contributed data to the study and to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.A. reports contributions to advisory boards for Roche Canada, Janssen, Pfizer, and AbbVie. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sarit Assouline, Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, 3755 Cote Ste Catherine, Suite E725, Montreal, QC H3T 1E2, Canada; e-mail: sarit.assouline@mcgill.ca.

References

Author notes

S.A. and S.L. contributed equally to this study.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.