Key Points

MYD88L265P mutation is insufficient to drive malignant transformation by itself.

MYD88L265P promotes a non-clonal B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder with some features of LPL/WM and the potential to transform to DLBCL in older mice.

Abstract

MYD88L265P is the most common mutation in lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia (LPL/WM) and one of the most frequent in poor-prognosis subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Although inhibition of the mutated MYD88 pathway has an adverse impact on LPL/WM and DLBCL cell survival, its role in lymphoma initiation remains to be clarified. We show that in mice, human MYD88L265P promotes development of a non-clonal, low-grade B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder with several clinicopathologic features that resemble human LPL/WM, including expansion of lymphoplasmacytoid cells, increased serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) concentration, rouleaux formation, increased number of mast cells in the bone marrow, and proinflammatory signaling that progresses sporadically to clonal, high-grade DLBCL. Murine findings regarding differences in the pattern of MYD88 staining and immune infiltrates in the bone marrows of MYD88 wild-type (MYD88WT) and MYD88L265P mice are recapitulated in the human setting, which provides insight into LPL/WM pathogenesis. Furthermore, histologic transformation to DLBCL is associated with acquisition of secondary genetic lesions frequently seen in de novo human DLBCL as well as LPL/WM-transformed cases. These findings indicate that, although the MYD88L265P mutation might be indispensable for the LPL/WM phenotype, it is insufficient by itself to drive malignant transformation in B cells and relies on other, potentially targetable cooperating genetic events for full development of lymphoma.

Introduction

Recent studies using whole-genome sequencing have uncovered the genetic landscape of hematologic malignancies. Among the most common alterations is a gain-of-function mutation (L265P) in the MYD88 gene, which is exceptionally high in lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia (LPL/WM; 90%-100%).1-4 The MYD88L265P mutation is highly prevalent in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), particularly in a poor-prognosis molecular subtype of activated B-cell (ABC) DLBCL (50%) termed C5/MCD5,6 and in extranodal variants of DLBCL.7,8 Despite recent advances in treatment, LPL/WM and ABC DLBCL remain challenging clinical problems.9,10 Therefore, there is an urgent need to better understand the molecular and cellular roles of the specific genetic lesions identified by high-throughput genetic analysis that drive lymphomagenesis.

The MYD88L265P mutation leads to spontaneous assembly of a protein complex called the myddosome, which activates NF-κB signaling.11-13 It was recently shown that in LPL/WM and DLBCL cells, MYD88 and other components of the myddosome aggregate into a larger multiprotein complex with TLR9 and BCR called My-T-BCR.14 Genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of MYD88L265P signaling is toxic to LPL/WM and ABC DLBCL cells.11,12 Although these findings rationalize the development of MYD88L265P-targeted therapeutic strategies, the exact role of this mutated protein in lymphoma initiation, and its ability to promote neoplastic transformation, are still not fully understood.

Although a knockin model of the murine L252P mutation (corresponding to human L265P) developed a polyclonal lymphoproliferative disorder (LPD) that progressed to a BCL6– DLBCL,15 the long latency of DLBCL occurrence suggests acquisition of spontaneous cooperating mutations. Moreover, the LPD in the L252P model was described as “a largely monomorphic lymphoid cell population with indolent appearance,” lacking the morphologic features of LPL/WM.15 We generated transgenic mice expressing the human MYD88 wild-type (MYD88WT) or MYD88L265P protein in germinal center (GC) and post-GC B cells, primarily because of the above results, along with these 4 observations: (1) the high incidence of the L265P mutation in human LPL/WM,1-4 (2) the structural differences between the human and mouse proteins,16 (3) the lack of reports about spontaneous development of LPL/WM-like tumors in mice,17 and (4) the potential utility of an animal model of human MYD88L265P for targeted drug screens. Here, we show that the MYD88L265P mutation (despite inducing downstream NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation) is insufficient to drive malignant transformation by itself, although it does promote a non-clonal, low-grade B-cell LPD with several clinicopathologic features resembling LPL/WM, which occasionally undergoes transformation to DLBCL harboring secondary mutations and expressing BCL6, as documented for human DLBCL cases transformed from LPL/WM.18,19

Materials and methods

Transgenic mice

Conditional hMYD88(WT)LSL and hMYD88(L265P)LSL transgenic mice were generated using a modified site-specific integration method,20 in which the tetracycline-responsive promoter was replaced with a CAG promoter and lox-stop-lox (LSL) cassette.21 Targeting vectors harboring the human MYD88WT or MYD88L265P complementary DNA downstream of the LSL cassette were electroporated together with an Flp recombinase-expressing plasmid into the C2 mouse embryonic stem cell line. Targeted integration of the MYD88 gene at flippase recognition target sites downstream of the mouse Col1A1 gene activated hygromycin resistance enabling selection. Positive clones were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts, which gave rise to chimeras and eventually to transgenic mice. To remove the LSL cassette, hMYD88 mice were crossed with those bearing AIDCre.22 All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC 05-065) of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Human samples

Archival paraffin-embedded bone marrow (BM) biopsies from patients with LPL/WM were obtained from the Pathology Department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Use of human material was approved by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board (IRB 01-206) in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Histopathology, immunohistochemistry (IHC), immunofluorescence, and immunoblotting

Histopathology, IHC, immunofluorescence, and immunoblotting analyses were performed according to standard protocols and manufacturers’ recommendations. For details, see supplemental Materials and methods.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

To induce T-cell–dependent B-cell responses and GC formation, which facilitated cell sorting and flow cytometry analysis in young animals, mice were immunized by intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 108 sheep red blood cells (Innovative Research, Novi, MI) in 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline and analyzed 10 days later, as described.23 Single-cell suspensions of mouse splenocytes or lymph node (LN) cells were isolated by pushing minced tissue through a strainer. Red blood cells were lysed, and leukocytes were stained with Zombie Aqua (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) and primary antibodies (supplemental Table 1) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Cells were analyzed using an LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) or fluorescence-activated cell sorted (FACS) using FACSAria II (BD Biosciences; gating indicated in Figure 2H). Flow cytometric data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Polymerase chain reaction analysis, clonality assessment, and whole-exome sequencing

For polymerase chain reaction analysis of the LSL cassette deletion, DNA was isolated from cells sorted by using FACS with the AllPrep DNA/RNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), amplified using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), separated on agarose gel, and visualized with a ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). DNA from LNs, spleens, tumors, liver, and tails was isolated using a Gentra Puregene kit (Qiagen). MYD88 transgenes were sequenced using Sanger sequencing. IgH gene rearrangements for lymphoma clonality assessment were analyzed using Southern blotting as described.24 Whole-exome sequencing was performed on 3 DLBCL and tail sample pairs as well as 1 tail sample from a healthy animal as an additional control. For details, see supplemental Materials and methods.

Serum protein electrophoresis and multiplex immunoassays

Serum was analyzed on SPIFE Serum Protein Gels with SPIFE 3000 gel electrophoresis (Helena Laboratories, Beaumont, TX). Mouse Magnetic Luminex Assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and Mouse Immunoglobulin Isotyping Magnetic Bead Panel (Millipore, Burlington, MA) kits were used to assess serum cytokines and immunoglobulin (Ig) concentrations, respectively, according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

Results

Aicda-driven overexpression of MYD88L265P induces abnormal inflammatory changes

To investigate the oncogenic potential of the somatic MYD88L265P mutation, we cloned WT or L265P-mutated human MYD88 complementary DNA sequences into the targeting vector (Figure 1A). Because both human LPL/WM and ABC DLBCL originate from post-GC B cells,25,26 we deleted the LSL stop cassette to overexpress human MYD88WT or MYD88L265P-mutated proteins in antigen-experienced B cells using Aicda-driven Cre recombinase. We achieved this by breeding AIDCre/+;MYD88(WT)LSL/– and AIDCre/+;MYD88(L265P)LSL/– mice, referred to as MYD88WT and MYD88L265P, respectively, and we used AIDCre/+ mice (referred to as AIDCre) as controls. We confirmed the presence of WT or L265P-mutated human MYD88 transgene sequences in the spleens of both transgenic mice (Figure 1B).

Generation and validation of conditional hMYD88(L265P)LSLtransgenic mouse model. (A) Schematic representation of the targeting vector integration site downstream of the mouse Col1A1 gene that supports high transgene expression in a variety of cell types including B cells. WT or L265P-mutated human MYD88 complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences were cloned into the targeting vector downstream of the loxP-flanked stop cassette (LSL) and electroporated together with an Flp recombinase-expressing plasmid into the C2 mouse embryonic stem cell line. C2 cells are engineered to acquire hygromycin resistance after targeted integration of the gene of interest at flippase recognition target (frt) sites. (B) Sanger sequencing of the human MYD88 sequence amplified from splenic genomic DNA isolated from transgenic mice. The presence of T>C transition results in the L265P mutation in MYD88L265P mice. (C) AIDCre-induced deletion of the LSL cassette assessed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers indicated as arrows in panel A in FACS splenic T cells and GC B cells from MYD88WT (n = 3) and MYD88L265P (n = 3) mice immunized with sheep red blood cells (SRBCs). loxP-flanked sequence: 640 bp; deleted: 330 bp. (D) Immunoblot analysis of MYD88 protein expression and p65 (S534) phosphorylation in FACS splenic GC B cells from AIDCre (n = 2), MYD88WT (n = 2), and MYD88L265P (n = 2) mice immunized with SRBCs relative to actin. (E) Immunohistochemical analysis of MYD88 expression within GCs of AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice. GCs were identified based on morphology and the presence of apoptotic bodies as well as Ki-67 staining in serial consecutive sections. Note punctate, cytoplasmic MYD88 staining in the MYD88L265P (white arrowheads) but not MYD88WT or AIDCre mice. Scale bars, 20 µm (see also supplemental Figure 1A). (F) Immunofluorescence analysis of p65 (white) subcellular localization within GC B cells (peanut agglutinin [PNA]; green) in spleens from AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice immunized with SRBCs (top and middle). Lower-magnification images (×40) were quantified using ImageJ (bottom). Gates were set up to quantify voxels with high intensity of p65 and low intensity of PNA staining or high intensity of PNA and low intensity of p65 staining. The numbers represent mean intensity of voxels within the gated region, which is proportional to the number of events gated. Note increased nuclear p65 staining (quantified as voxels positive for p65 and negative for PNA, which stain cell membrane) in the MYD88WT and MYD88L265P but not AIDCre mice. Scale bars, 20 µm (see also supplemental Figure 1B-C). (G) Spleen weights in 8- to 16-week-old AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice (n = 3 per group). Graphs depict the mean ± standard deviation (SD). P values were calculated by using Welch’s t test (left). Representative gross pictures of spleens (Sp) and LNs are shown on the right. Scale bars, 1 cm. Histologic (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E]) and IHC stains of indicated cell markers on consecutive serial sections from spleens (H) and BMs (I) from representative 8- to 16-week-old AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice. B220, B cells; CD3, T cells; CD138, plasma cells. Scale bars: white, 100 µm; black, 25 µm. pA, polyadenylation sequences; CAG, cytomegalovirus enhancer/chicken β-actin promoter; PGK ATGfrt, phosphoglycerate kinase 1 promoter followed by ATG initiation codon restoring hygromycin resistance gene expression.

Generation and validation of conditional hMYD88(L265P)LSLtransgenic mouse model. (A) Schematic representation of the targeting vector integration site downstream of the mouse Col1A1 gene that supports high transgene expression in a variety of cell types including B cells. WT or L265P-mutated human MYD88 complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences were cloned into the targeting vector downstream of the loxP-flanked stop cassette (LSL) and electroporated together with an Flp recombinase-expressing plasmid into the C2 mouse embryonic stem cell line. C2 cells are engineered to acquire hygromycin resistance after targeted integration of the gene of interest at flippase recognition target (frt) sites. (B) Sanger sequencing of the human MYD88 sequence amplified from splenic genomic DNA isolated from transgenic mice. The presence of T>C transition results in the L265P mutation in MYD88L265P mice. (C) AIDCre-induced deletion of the LSL cassette assessed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers indicated as arrows in panel A in FACS splenic T cells and GC B cells from MYD88WT (n = 3) and MYD88L265P (n = 3) mice immunized with sheep red blood cells (SRBCs). loxP-flanked sequence: 640 bp; deleted: 330 bp. (D) Immunoblot analysis of MYD88 protein expression and p65 (S534) phosphorylation in FACS splenic GC B cells from AIDCre (n = 2), MYD88WT (n = 2), and MYD88L265P (n = 2) mice immunized with SRBCs relative to actin. (E) Immunohistochemical analysis of MYD88 expression within GCs of AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice. GCs were identified based on morphology and the presence of apoptotic bodies as well as Ki-67 staining in serial consecutive sections. Note punctate, cytoplasmic MYD88 staining in the MYD88L265P (white arrowheads) but not MYD88WT or AIDCre mice. Scale bars, 20 µm (see also supplemental Figure 1A). (F) Immunofluorescence analysis of p65 (white) subcellular localization within GC B cells (peanut agglutinin [PNA]; green) in spleens from AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice immunized with SRBCs (top and middle). Lower-magnification images (×40) were quantified using ImageJ (bottom). Gates were set up to quantify voxels with high intensity of p65 and low intensity of PNA staining or high intensity of PNA and low intensity of p65 staining. The numbers represent mean intensity of voxels within the gated region, which is proportional to the number of events gated. Note increased nuclear p65 staining (quantified as voxels positive for p65 and negative for PNA, which stain cell membrane) in the MYD88WT and MYD88L265P but not AIDCre mice. Scale bars, 20 µm (see also supplemental Figure 1B-C). (G) Spleen weights in 8- to 16-week-old AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice (n = 3 per group). Graphs depict the mean ± standard deviation (SD). P values were calculated by using Welch’s t test (left). Representative gross pictures of spleens (Sp) and LNs are shown on the right. Scale bars, 1 cm. Histologic (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E]) and IHC stains of indicated cell markers on consecutive serial sections from spleens (H) and BMs (I) from representative 8- to 16-week-old AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice. B220, B cells; CD3, T cells; CD138, plasma cells. Scale bars: white, 100 µm; black, 25 µm. pA, polyadenylation sequences; CAG, cytomegalovirus enhancer/chicken β-actin promoter; PGK ATGfrt, phosphoglycerate kinase 1 promoter followed by ATG initiation codon restoring hygromycin resistance gene expression.

Next, we evaluated the efficacy of AIDCre-mediated induction of MYD88 transgene expression and activity in vivo. We detected deletion of the LSL cassette in FACS GC B cells, but not T cells, from both MYD88WT and MYD88L265P mice (Figure 1C). MYD88 protein abundance consistently increased in GC B cells from both MYD88WT and MYD88L265P mice compared with AIDCre mice (Figure 1D-E). However, expression of MYD88L265P was lower than that of MYD88WT, suggesting different maturation and/or reduced stability of the mutant protein. Moreover, we observed different patterns of subcellular distribution between the 2 forms. Although MYD88WT was evenly distributed among the cells, MYD88L265P was confined to small foci within mouse GC cells and transfected HEK293T cells, suggesting that the L265P mutation enhances oligomerization and resembles formation of myddosome/My-T-BCR13,14 in vivo (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 1A). We subsequently found that overexpression of both human MYD88L265P and MYD88WT enhanced nuclear localization of p65 in mouse GC B cells and transfected HEK293T cells (Figure 1F; supplemental Figure 1B-C). However, only the MYD88L265P cells demonstrated decreased p65 (S534) phosphorylation (Figure 1D). Blockage of p65 (S534) phosphorylation was previously shown to increase p65 stability and enhance NF-κB–dependent gene expression,27 suggesting different activities of mutated vs WT protein. These findings confirm that AIDCre induces expression of human MYD88L265P, resulting in activation of its downstream targets in murine GC B cells.

To initially assess the effect of MYD88 transgene expression on development of lymphoid organs and B cells, we examined 8- to 16-week-old AIDCre, MYD88WT, or MYD88L265P mice. Gross pathologic examination revealed moderately enlarged spleens in the MYD88L265P compared with AIDCre and MYD88WT mice (Figure 1G). Conversely, no obvious histologic changes were observed in the spleens and BMs of MYD88L265P mice compared with AIDCre and MYD88WT animals (Figure 1H-I). Immunostaining for B220 and CD3 showed normal B-cell:T-cell ratios in the spleens (Figure 1H). Likewise, there was no substantial increase in the number of B cells and CD138+ plasma cells in the BMs of MYD88L265P compared with control mice (Figure 1I). These results show that expression of MYD88WT and MYD88L265P transgenes induce no major histopathologic changes during early development of lymphoid organs.

Starting at 8 weeks of age, however, 90% of MYD88L265P mice, but none of the AIDCre and MYD88WT controls, began to develop skin rash and hair loss restricted to the submandibular areas, even as the mice aged (Figure 2A). We detected a mixed cellular infiltrate composed predominantly of T cells and histiocytes as well as scattered mast cells and B cells in the dermis of MYD88L265P mice (Figure 2B-F). Furthermore, regional cervical LNs were found to be particularly enlarged when compared with other LNs in MYD88L265P mice. This size change was caused by cystic formation vs an inflammatory response or lymphoproliferation only in the cervical LNs (Figure 2G).

Skin, immune cell, and serum Ig changes in MYD88L265Pmice. (A) Representative gross pathology photographs of submandibular skin showing dermatitis and alopecia in MYD88L265P but not MYD88WT mice. (B) H&E, Giemsa, and IHC stains of indicated cell markers on serial submandibular skin sections from representative MYD88WT and MYD88L265P mice. Giemsa stain was used to identify mast cells; F4/80, macrophages. Scale bars: white, 10 µm; black, 100 µm. Percentage of T cells (C), macrophages (D), and mast cells (E) or number of mast cells relative to the tissue area (F) per field in the submandibular skin of MYD88WT and MYD88L265P mice. Measurements were made with inForm Cell Analysis Software analyzing 8 fields per genotype. Graphs depict the mean ± SD. P values were calculated by using Welch’s t test. (G) Histologic (H&E) analysis of representative cervical LNs demonstrating cyst development in MYD88L265P but not in AIDCre or MYD88WT mice. Scale bars: white, 50 µm; black, 500 µm. Representative density plots (H) and graphs (I) depicting the mean ± SD of flow cytometric analysis of splenic lymphoid cell subpopulations from AIDCre (n = 6), MYD88WT (n = 7), and MYD88L265P (n = 6) mice immunized with SRBCs. (J) Serum Ig concentrations assessed using multiplex immunoassay in MYD88L265P mice grouped according to severity of submandibular skin lesions. Graphs depict the median ± 25th to 75th percentile. P values were calculated by using Mann-Whitney U test. (K) Percentage of MYD88L265P mice classified by the severity of submandibular skin lesions with serum IL-6 concentrations >49 pg/mL assessed using multiplex immunoassay. P value was calculated by using Fisher’s exact test. (L) IHC stains of indicated cytokines on serial submandibular skin sections from representative MYD88WT and MYD88L265P mice. Scale bars: white, 10 µm; black, 100 µm.

Skin, immune cell, and serum Ig changes in MYD88L265Pmice. (A) Representative gross pathology photographs of submandibular skin showing dermatitis and alopecia in MYD88L265P but not MYD88WT mice. (B) H&E, Giemsa, and IHC stains of indicated cell markers on serial submandibular skin sections from representative MYD88WT and MYD88L265P mice. Giemsa stain was used to identify mast cells; F4/80, macrophages. Scale bars: white, 10 µm; black, 100 µm. Percentage of T cells (C), macrophages (D), and mast cells (E) or number of mast cells relative to the tissue area (F) per field in the submandibular skin of MYD88WT and MYD88L265P mice. Measurements were made with inForm Cell Analysis Software analyzing 8 fields per genotype. Graphs depict the mean ± SD. P values were calculated by using Welch’s t test. (G) Histologic (H&E) analysis of representative cervical LNs demonstrating cyst development in MYD88L265P but not in AIDCre or MYD88WT mice. Scale bars: white, 50 µm; black, 500 µm. Representative density plots (H) and graphs (I) depicting the mean ± SD of flow cytometric analysis of splenic lymphoid cell subpopulations from AIDCre (n = 6), MYD88WT (n = 7), and MYD88L265P (n = 6) mice immunized with SRBCs. (J) Serum Ig concentrations assessed using multiplex immunoassay in MYD88L265P mice grouped according to severity of submandibular skin lesions. Graphs depict the median ± 25th to 75th percentile. P values were calculated by using Mann-Whitney U test. (K) Percentage of MYD88L265P mice classified by the severity of submandibular skin lesions with serum IL-6 concentrations >49 pg/mL assessed using multiplex immunoassay. P value was calculated by using Fisher’s exact test. (L) IHC stains of indicated cytokines on serial submandibular skin sections from representative MYD88WT and MYD88L265P mice. Scale bars: white, 10 µm; black, 100 µm.

To examine whether this focal dermal phenotype was associated with systemic alterations of immune cells, we immunized mice with sheep red blood cells to induce GC formation and measured lymphocyte subpopulations in the spleens using flow cytometry (Toll-like receptor agonists were not tested because they may blunt the differences between mice with and without the MYD88L265P mutation). Significant differences in total numbers of T cells, B cells, and plasma cells were not observed, although the percentage of plasma cells was elevated in MYD88L265P vs AIDCre and MYD88WT mice (Figure 2H-I). Increased numbers of plasma cells were also detected using IHC (supplemental Figure 1D).

Next, we performed a multiplex immunoassay on serum samples from MYD88L265P mice divided into groups based on the severity of their skin lesions: group I contained mice with mild rash and alopecia, which did not progress or form major fibrosis over time, and group II contained mice whose skin lesions progressed to lip retraction and fibrosis. We found that MYD88L265P mice in group II had significantly increased concentrations of IgM, IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG3, but not IgA, when compared with littermates in group I (Figure 2J). Accordingly, we evaluated systemic inflammation by measuring the abundance of interleukin-6 (IL-6), a major proinflammatory cytokine.28 Higher IL-6 levels were present in the serum of group II compared with group I (Figure 2K). Moreover, we observed higher IL-6 abundance in mast and stromal cells in the dermis of MYD88L265P compared with MYD88WT mice (Figure 2L). Although CXCL13 serum levels did not correlate with the severity of skin lesions, its expression was locally increased in mast and stromal cell similar to that of IL-6 (Figure 2L). These findings show that neither skin lesions nor expression of MYD88 transgenes in young animals induces conspicuous changes in the lymphoid organ B-cell:T-cell ratio or in GC response to acute activation. However, the focal skin changes are associated with systemic proinflammatory signaling in MYD88L265P mice.

MYD88L265P mice develop a low-grade, non-clonal LPD

To elucidate the role of MYD88L265P protein in the pathogenesis of mature B-cell neoplasms, we evaluated AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice over a 2-year aging period. Starting at 20 weeks, MYD88L265P mice developed progressive lethargy, and by 67 weeks, 50% of the mice (11 of 22) had to be euthanized (Figure 3A). At autopsy, we observed a moderate splenic enlargement (not correlated with the severity of the submandibular skin lesions), along with generalized massive LN enlargement in 15 of 22 animals (Figure 3B-C); 33% of the mice exhibited macroscopic alterations consisting of lymphoid infiltrates in the liver and/or lungs (supplemental Figure 2A). Ill-defined white pulp and follicles, poorly demarcated from the reduced red pulp and interfollicular areas, were exclusively observed by histologic analysis in spleen and LNs from MYD88L265P mice (Figure 3D-E). In line with the gross pathologic examination, LN architecture was more distorted than the splenic architecture. T-cell areas were mainly unaffected. In contrast, we noted an expansion of B220+CD138DIMCD5– intermediate-size to large plasmacytoid cells, with greater expression of IgM relative to IgG and a low proliferation rate (5%-10% Ki-67+ cells) in MYD88L265P compared with control mice (Figure 3D-E). No major infiltration of atypical cells was detected in the BMs of examined mice; however, a significant increase in the number of T cells, with an excess of CD8+ over CD4+ cells, and mast cells was observed in MYD88L265P compared with age-matched control mice (Figure 3F; supplemental Figure 2B). Of note, plasmacytoid lymphocytes from MYD88L265P mice showed the same focal pattern of MYD88 staining as the premalignant GC B cells (Figures 1E and 3E). No rearranged clonal bands for the IgH locus were detected by Southern blot analysis (Figure 3G), demonstrating that MYD88L265P overexpression drives development of a premalignant, non-clonal, low-grade B-cell LPD with plasmacytic differentiation.

Development of a non-clonal, low-grade B-cell LPD in MYD88L265Pmice. (A) Kaplan-Meier plots illustrating event-free survival of aging cohorts of AIDCre (n = 13), MYD88WT (n = 12), and MYD88L265P (n = 28) mice. P value was calculated by using a log-rank test. (B) Spleen weights in aged AIDCre (n = 5) and MYD88WT (n = 5) control mice and MYD88L265P (n = 11) mice with LPD. Graphs depict the mean ± SD. P values were calculated by using Welch’s t test. (C) Gross images of spleens and LNs from representative MYD88L265P mice with low-grade B-cell LPD. Scale bar, 1 cm. Histologic and IHC stains of indicated markers on serial spleen (D), LN (E), and BM (F) sections from representative, age-matched AIDCre and MYD88WT control mice, and 1 MYD88L265P mouse with LPD. Note expansion of plasmacytoid lymphocytes (white arrowheads) in the MYD88L265P mice compared with controls; and punctate, cytoplasmic MYD88 staining in the MYD88L265P LPD cells (black arrowheads). Scale bars: white, 50 µm; black, 500 µm; yellow, 5 µm (see also supplemental Figure 2B). (G) Clonality evaluated by Southern blot analysis of the IgH gene in DNA isolated from LNs of MYD88L265P (n = 7) mice with LPD. GL, non-rearranged germline band.

Development of a non-clonal, low-grade B-cell LPD in MYD88L265Pmice. (A) Kaplan-Meier plots illustrating event-free survival of aging cohorts of AIDCre (n = 13), MYD88WT (n = 12), and MYD88L265P (n = 28) mice. P value was calculated by using a log-rank test. (B) Spleen weights in aged AIDCre (n = 5) and MYD88WT (n = 5) control mice and MYD88L265P (n = 11) mice with LPD. Graphs depict the mean ± SD. P values were calculated by using Welch’s t test. (C) Gross images of spleens and LNs from representative MYD88L265P mice with low-grade B-cell LPD. Scale bar, 1 cm. Histologic and IHC stains of indicated markers on serial spleen (D), LN (E), and BM (F) sections from representative, age-matched AIDCre and MYD88WT control mice, and 1 MYD88L265P mouse with LPD. Note expansion of plasmacytoid lymphocytes (white arrowheads) in the MYD88L265P mice compared with controls; and punctate, cytoplasmic MYD88 staining in the MYD88L265P LPD cells (black arrowheads). Scale bars: white, 50 µm; black, 500 µm; yellow, 5 µm (see also supplemental Figure 2B). (G) Clonality evaluated by Southern blot analysis of the IgH gene in DNA isolated from LNs of MYD88L265P (n = 7) mice with LPD. GL, non-rearranged germline band.

Analysis of LNs using flow cytometry did not reveal any significant differences in the number of total B cells between MYD88L265P LPD mice and AIDCre or MYD88WT controls (Figure 4A). However, we detected significant expansion of GC B cells in MYD88L265P LPDs compared with AIDCre and MYD88WT mice (Figure 4A). Moreover, the percentage of plasma cells was increased in MYD88L265P LPDs compared with those in AIDCre mice (Figure 4A). These findings suggest that although MYD88L265P overexpression might not stimulate transient B-cell activation, its chronic, long-term signaling promotes progressive expansion of GC B cells over time.

LPL/WM features of LPD in MYD88L265Pmice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of lymphocyte subpopulations in LNs from aged AIDCre (n = 7) and MYD88WT (n = 7) control mice and MYD88L265P (n = 11) mice with LPD. Graphs depict the mean ± SD. P values were calculated by using Welch’s t test. (B) Serum protein electrophoresis of aged AIDCre (n = 2) and MYD88WT (n = 2) control mice and of MYD88L265P (n = 9) mice with LPD. Note increased abundance of diffuse gamma globulins (black arrowheads) in MYD88L265P mice compared with controls. A positive (Pos.) control containing a sharp band of gamma globulins (M spike) is shown for comparison. (C) Serum IgM concentrations assessed using multiplex immunoassay in aged AIDCre (n = 7), MYD88WT (n = 7), and MYD88L265P (n = 23) mice. Orange points represent DLBCL animals in the MYD88L265P cohort. Graphs depict the median ± 25th to 75th percentile. P values were calculated by using the Mann-Whitney U test (see also supplemental Figure 2C). (D) Peripheral blood smears demonstrating rouleaux formation of red blood cells in representative MYD88L265P (n = 3) mice with LPD. (E) Serum IL-6 concentrations assessed by multiplex immunoassay in aged AIDCre (n = 8), MYD88WT (n = 8), and MYD88L265P (n = 24) mice. Orange points represent DLBCL animals in the MYD88L265P cohort; the dotted line indicates the assay sensitivity threshold. Graphs depict the median ± 25th to 75th percentile. P value was calculated by using Fisher’s exact test. P value for the analysis with DLBCL samples omitted is .0491. (F) Serum CXCL13 concentrations assessed by multiplex immunoassay in aged AIDCre (n = 7), MYD88WT (n = 6), and MYD88L265P mice with (n = 7) or without (n = 15) macroscopic liver and/or lung changes. Orange points represent DLBCL animals in the MYD88L265P cohort. Graphs depict the median ± 25th to 75th percentile. P values were calculated by using the Mann-Whitney U test. P values for the analysis with DLBCL samples omitted are .0424, .0381, and .0139 for comparison of MYD88L265P mice with macroscopic liver and/or lung changes with AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice without macroscopic liver and/or lung changes, respectively (see also supplemental Figure 2A). Alter., alterations.

LPL/WM features of LPD in MYD88L265Pmice. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of lymphocyte subpopulations in LNs from aged AIDCre (n = 7) and MYD88WT (n = 7) control mice and MYD88L265P (n = 11) mice with LPD. Graphs depict the mean ± SD. P values were calculated by using Welch’s t test. (B) Serum protein electrophoresis of aged AIDCre (n = 2) and MYD88WT (n = 2) control mice and of MYD88L265P (n = 9) mice with LPD. Note increased abundance of diffuse gamma globulins (black arrowheads) in MYD88L265P mice compared with controls. A positive (Pos.) control containing a sharp band of gamma globulins (M spike) is shown for comparison. (C) Serum IgM concentrations assessed using multiplex immunoassay in aged AIDCre (n = 7), MYD88WT (n = 7), and MYD88L265P (n = 23) mice. Orange points represent DLBCL animals in the MYD88L265P cohort. Graphs depict the median ± 25th to 75th percentile. P values were calculated by using the Mann-Whitney U test (see also supplemental Figure 2C). (D) Peripheral blood smears demonstrating rouleaux formation of red blood cells in representative MYD88L265P (n = 3) mice with LPD. (E) Serum IL-6 concentrations assessed by multiplex immunoassay in aged AIDCre (n = 8), MYD88WT (n = 8), and MYD88L265P (n = 24) mice. Orange points represent DLBCL animals in the MYD88L265P cohort; the dotted line indicates the assay sensitivity threshold. Graphs depict the median ± 25th to 75th percentile. P value was calculated by using Fisher’s exact test. P value for the analysis with DLBCL samples omitted is .0491. (F) Serum CXCL13 concentrations assessed by multiplex immunoassay in aged AIDCre (n = 7), MYD88WT (n = 6), and MYD88L265P mice with (n = 7) or without (n = 15) macroscopic liver and/or lung changes. Orange points represent DLBCL animals in the MYD88L265P cohort. Graphs depict the median ± 25th to 75th percentile. P values were calculated by using the Mann-Whitney U test. P values for the analysis with DLBCL samples omitted are .0424, .0381, and .0139 for comparison of MYD88L265P mice with macroscopic liver and/or lung changes with AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice without macroscopic liver and/or lung changes, respectively (see also supplemental Figure 2A). Alter., alterations.

Because LPL/WM is characterized by IgM gammopathy and the MYD88L265P LPD cells had a large excess of IgM, we examined the serum proteins of the mice by electrophoresis. In line with the previous findings, we detected diffuse bands, indicating a polyclonal increase in gamma globulins in MYD88L265P compared with AIDCre and MYD88WT mice (Figure 4B). Moreover, multiplex immunoassay revealed that serum concentrations of IgM, but not IgG1, IgG3, or IgA, were significantly higher in MYD88L265P compared with controls (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 2C). IgG2b concentration was significantly increased in MYD88L265P compared with MYD88WT mice and showed a positive correlation with IgM concentrations (r = 0.7373; supplemental Figure 2C-D). Rouleaux formation was subsequently detected in stains of peripheral blood smears (Figure 4D).

Given the focal skin lesions in MYD88L265P mice, as well as the increase in proinflammatory cytokine secretion in LPL/WM patients,29 we examined serum IL-6 abundance and found higher concentrations in MYD88L265P vs AIDCre and MYD88WT mice (Figure 4E). Furthermore, we detected a higher concentration of CXCL13 (a B-cell chemoattractant that is elevated in LPL/WM patients)30 in the serum of MYD88L265P mice with macroscopic lung or liver lymphoid infiltrates at autopsy in comparison with other groups (Figure 4F). Taken together, these findings show that MYD88L265P mice develop a non-clonal, B-cell lymphoproliferation with certain characteristic features of LPL/WM, such as plasmacytic differentiation, increased IgM levels, rouleaux formation, and proinflammatory signaling.

With longer latency, MYD88L265P mice acquire secondary genetic lesions and develop clonal high-grade B-cell lymphoma

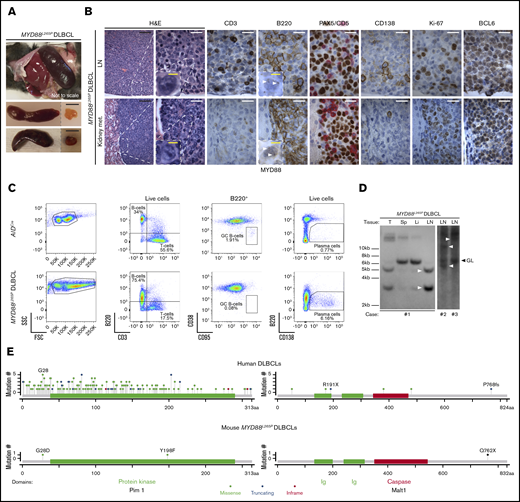

During the aging period, specifically at older ages (median of 85.8 weeks vs 56.3 weeks for LPD), 4 of 22 MYD88L265P mice developed a more aggressive disease characterized by massive enlargement of spleen and LNs (Figure 5A). Focal skin lesions were limited to a mild rash in these animals. Therefore, we examined the lymphoid organs by histology, IHC, and flow cytometry. Tissue architecture was distorted by a diffuse infiltrate of medium-size to large B220+BCL6+CD138–CD5– cells with a high proliferation rate (40%-80% Ki-67+ cells). The cells were admixed with residual CD138+ plasmacytoid cells (Figure 5B-C). In addition, the neoplastic cells infiltrated other organs, including kidney, liver, lung, and BM (data not shown; Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 2A). Small focal infiltrates were also detected in the brains and at the outer meninges (data not shown). Southern blot analysis of the IgH gene locus revealed that the neoplasms were clonal (Figure 5D). Large B cells showed a focal pattern of MYD88 immunostaining, indicating its continuous activation in these transformed cells. We also detected higher concentrations of serum CXCL13 in the high-grade cases compared with the other MYD88L265P (P = .0091), MYD88WT (P = .0238), and AIDCre (P = .0167) mice (Figure 4F). These observations were consistent with the clinicopathologic diagnosis of DLBCL in human patients.

Development of DLBCL in MYD88L265Pmice. (A) Gross pathology images of spleens (top, in situ; bottom, dissected) and LNs from MYD88L265P mice with DLBCL. Scale bars, 1 cm. (B) Histologic and IHC stains of indicated markers on serial LN (top) and kidney metastasis (met.) (bottom) sections from MYD88L265P mice (n = 2) with DLBCL. Note punctate cytoplasmic MYD88 staining in the lymphoma cells (white arrowheads). Scale bars: white, 20 µm; black, 100 µm; yellow, 5 µm. (C) Density plots of flow cytometric analysis of indicated lymphocyte subpopulations in LNs from representative, age-matched AIDCre control and MYD88L265P DLBCL mice. (D) Clonality evaluated by Southern blot analysis of the IgH gene in DNA isolated from LNs, spleen (Sp), liver (Li), and tumor (T) of MYD88L265P (n = 3) mice with DLBCL. Clonal rearranged bands are indicated with white arrowheads. (E) Location of murine MYD88L265P and corresponding human DLBCL6 somatic mutations in affected proteins.

Development of DLBCL in MYD88L265Pmice. (A) Gross pathology images of spleens (top, in situ; bottom, dissected) and LNs from MYD88L265P mice with DLBCL. Scale bars, 1 cm. (B) Histologic and IHC stains of indicated markers on serial LN (top) and kidney metastasis (met.) (bottom) sections from MYD88L265P mice (n = 2) with DLBCL. Note punctate cytoplasmic MYD88 staining in the lymphoma cells (white arrowheads). Scale bars: white, 20 µm; black, 100 µm; yellow, 5 µm. (C) Density plots of flow cytometric analysis of indicated lymphocyte subpopulations in LNs from representative, age-matched AIDCre control and MYD88L265P DLBCL mice. (D) Clonality evaluated by Southern blot analysis of the IgH gene in DNA isolated from LNs, spleen (Sp), liver (Li), and tumor (T) of MYD88L265P (n = 3) mice with DLBCL. Clonal rearranged bands are indicated with white arrowheads. (E) Location of murine MYD88L265P and corresponding human DLBCL6 somatic mutations in affected proteins.

The prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, longer latency, and BCL6 expression18,19 suggested that these neoplasms might have arisen from the LPD by acquiring cooperative genetic alterations. We therefore performed whole-exome sequencing of 3 MYD88L265P DLBCLs and detected an average of 216 single nucleotide variants and 49 indels per sample (supplemental Table 2). Remarkably, somatic variants involved genes that are frequently mutated and/or constitute pathways perturbed in human DLBCLs, including some related to MYD88/NF-κB and BCR signaling.5,6 For several of these genes, which included Malt1, Klf2, Gna13, Dusp2, Pik3c2g, Pdgfrb, and Pim1, the location and impact of the mutations closely mirrored mutations documented in human DLBCL (Table 1). Two of 3 samples had Pim1 mutations (Figure 5E) and mutations in other genes targeted by aberrant somatic hypermutation.6 Taken together, these results point out potential secondary genetic lesions cooperating with MYD88L265P-promoted clonal lymphomagenesis and suggest that our MYD88L265P model recapitulates pathogenetic events observed in human DLBCL.

Human DLBCL-related somatic variants detected in mouse MYD88L265P DLBCLs

| Gene . | Mouse . | Human . | Notes . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue* . | Domain . | Downstream residue† . | Upstream residue† . | Domain . | aSHM‡ . | Mouse . | |

| Bclaf1 | Q18E | — | — | — | — | — | #2 |

| Dusp2 | L89V (L85) | Rhodanese | V66I | A96V/T | Rhodanese | Known | #2 |

| L67F | A99V/T/fs | ||||||

| L76P | E100D | ||||||

| E84D | L101P/F | ||||||

| P103L | |||||||

| Gna13 | R166Q | G-α | L152F | E167D | G-α | — | #1 |

| R166X | Q169H/X | ||||||

| V174E | |||||||

| F177S | |||||||

| L181X | |||||||

| Klf2 | G35D (G36) | — | E31D | N42D | — | Predicted | #3 |

| P32L/S | S43N | ||||||

| G36D | |||||||

| Malt1 | Q762X (Q754) | — | P768fs | R191X | — | — | #1 |

| Pdgfrb | V567A (V568) | Cytoplasmic | — | — | — | — | #2 |

| Pik3c2a | K391T (K390) | — | — | — | — | — | #2 |

| Pim1 | G28D | — | T23I | K29N | — | Known | #2 |

| K24N | E30K/D/Q/fs | ||||||

| L25V/M | K31R | ||||||

| A26P/T | E32K/Q/fs | ||||||

| P27S | P33S/T | ||||||

| G28D/A/D | |||||||

| Y198F | Kinase | L192V | D200N/H | Kinase | #3 | ||

| L193F/V | G203E/R | ||||||

| K194N | V206M/fs | ||||||

| T196I/S | Y207F | ||||||

| V197I | S208G/R/T | ||||||

| Gene . | Mouse . | Human . | Notes . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue* . | Domain . | Downstream residue† . | Upstream residue† . | Domain . | aSHM‡ . | Mouse . | |

| Bclaf1 | Q18E | — | — | — | — | — | #2 |

| Dusp2 | L89V (L85) | Rhodanese | V66I | A96V/T | Rhodanese | Known | #2 |

| L67F | A99V/T/fs | ||||||

| L76P | E100D | ||||||

| E84D | L101P/F | ||||||

| P103L | |||||||

| Gna13 | R166Q | G-α | L152F | E167D | G-α | — | #1 |

| R166X | Q169H/X | ||||||

| V174E | |||||||

| F177S | |||||||

| L181X | |||||||

| Klf2 | G35D (G36) | — | E31D | N42D | — | Predicted | #3 |

| P32L/S | S43N | ||||||

| G36D | |||||||

| Malt1 | Q762X (Q754) | — | P768fs | R191X | — | — | #1 |

| Pdgfrb | V567A (V568) | Cytoplasmic | — | — | — | — | #2 |

| Pik3c2a | K391T (K390) | — | — | — | — | — | #2 |

| Pim1 | G28D | — | T23I | K29N | — | Known | #2 |

| K24N | E30K/D/Q/fs | ||||||

| L25V/M | K31R | ||||||

| A26P/T | E32K/Q/fs | ||||||

| P27S | P33S/T | ||||||

| G28D/A/D | |||||||

| Y198F | Kinase | L192V | D200N/H | Kinase | #3 | ||

| L193F/V | G203E/R | ||||||

| K194N | V206M/fs | ||||||

| T196I/S | Y207F | ||||||

| V197I | S208G/R/T | ||||||

Human homolog residues are shown in parenthesis in case of heterogeneity.

Up to 5 missense or truncating mutations 20 amino acids downstream and upstream of the residue altered in mouse MYD88L265P DLBCLs. For MALT1, functionally related mutations are shown. Bold font indicates corresponding residues altered in mouse MYD88L265P and human DLBCLs or having the same effect in the case of Malt1. Based on Chapuy et al,5 Schmitz et al,6 and Reddy et al.54

Aberrant somatic hypermutation (aSHM), according to Schmitz et al.6

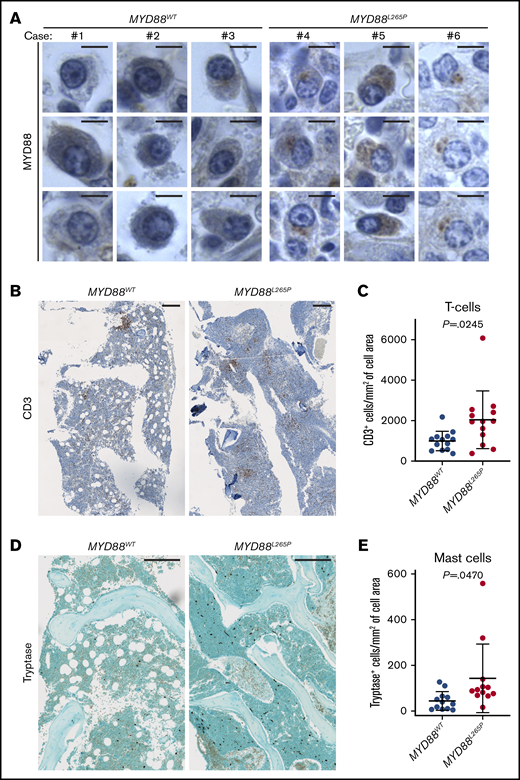

MYD88L265P leads to formation of protein aggregates and increases BM immune infiltration in LPL/WM patients

The focal pattern of MYD88 staining selectively observed in MYD88L265P cells prompted us to investigate whether it would enable differentiation of LPL/WM patients according to MYD88 mutations; especially since the presence of similar structures was recently shown to be a predictive marker in DLBCL.14 We found that plasmacytoid lymphocytes in BM biopsies from LPL/WM patients with MYD88L265P (n = 13) expressed a higher amount of MYD88 protein aggregated in focal structures when compared with MYD88WT patients (n = 11) (Figure 6A). This suggests that MYD88 immunostaining may be a useful diagnostic marker for detection of MYD88L265P mutation. However, this result needs to be validated in a much larger number of samples.

Implications of MYD88L265Pmurine model for human LPL/WM. (A) MYD88 expression in plasmacytoid lymphocytes in BM biopsies from LPL/WM patients without (n = 11) and with (n = 13) MYD88L265P mutation as evaluated by IHC staining. Three representative examples per each group are shown. Note punctate cytoplasmic staining of the MYD88L265P, but not WT, protein. Scale bars, 5 µm. T-cell infiltration of BM biopsies from LPL/WM patients without (n = 13) and with (n = 13) the MYD88L265P mutation. Representative IHC stains (B) and graphs (C) depicting the mean ± SD number of CD3+ T cells per cell annotated area (mm2) measured with HALO Image Analysis Software. Scale bars, 250 µm. P value was calculated by using Welch’s t test. Mast cell infiltration of BM biopsies from LPL/WM patients without (n = 12) and with (n = 12) the MYD88L265P mutation. Representative IHC stains (D) and graphs (E) depicting the mean ± SD number of tryptase+ mast cells per cell annotated area (mm2) measured with HALO Image Analysis Software. Scale bars, 250 µm. P value was calculated by using Welch’s t test.

Implications of MYD88L265Pmurine model for human LPL/WM. (A) MYD88 expression in plasmacytoid lymphocytes in BM biopsies from LPL/WM patients without (n = 11) and with (n = 13) MYD88L265P mutation as evaluated by IHC staining. Three representative examples per each group are shown. Note punctate cytoplasmic staining of the MYD88L265P, but not WT, protein. Scale bars, 5 µm. T-cell infiltration of BM biopsies from LPL/WM patients without (n = 13) and with (n = 13) the MYD88L265P mutation. Representative IHC stains (B) and graphs (C) depicting the mean ± SD number of CD3+ T cells per cell annotated area (mm2) measured with HALO Image Analysis Software. Scale bars, 250 µm. P value was calculated by using Welch’s t test. Mast cell infiltration of BM biopsies from LPL/WM patients without (n = 12) and with (n = 12) the MYD88L265P mutation. Representative IHC stains (D) and graphs (E) depicting the mean ± SD number of tryptase+ mast cells per cell annotated area (mm2) measured with HALO Image Analysis Software. Scale bars, 250 µm. P value was calculated by using Welch’s t test.

Finally, we evaluated the extent of T-cell and mast cell infiltration of BM biopsies from LPL/WM patients, given the increased immune infiltrates observed in BMs from MYD88L265P mice (Figure 3F; supplemental Figure 2B). Consistent with the murine findings, we detected significantly higher T-cell and mast cell density in BMs from MYD88L265P WM patients as compared with those in MYD88WT patients (Figure 6B-E), suggesting that aberrant MYD88 signaling may promote their migration into the BM niche. Notably, we observed lower lymphoplasmacytic involvement in BMs of MYD88WT compared with MYD88L265P cases. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the murine MYD88L265P model recapitulates many of the clinicopathologic features observed in human LPL/WM and DLBCL patients and provides a valuable resource for uncovering the pathogenesis of mutated MYD88.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that AIDCre-driven somatic activation of the MYD88L265P, but not the MYD88WT, transgene promotes a focal skin rash associated with increased systemic IL-6 signaling. With time, the majority of MYD88L265P mice develop a premalignant, non-clonal, low-grade LPD with clinicopathologic features resembling LPL/WM and progressing, albeit at low frequency, to clonal, high-grade DLBCL in aged mice. Recapitulation of the murine findings in the human setting corroborates their similarity and provides clinical correlations and insight into the pathogenesis of LPL/WM.

The exceptionally high prevalence of the MYD88L265P mutation in human LPL/WM indicates its important role in these neoplastic cells. However, the exact mechanism of action and whether it is sufficient to drive LPL/WM pathogenesis need clarification. Our findings showed that although human MYD88L265P alone is insufficient to induce full-blown LPL/WM neoplasia, it does foster emergence of LPL/WM-specific clinicopathologic features, including expansion of lymphoplasmacytic cells, elevated serum IgM concentration, rouleaux formation (which can be caused by increased Ig levels or inflammation),31 increased number of T- and mast cells in the BM, and proinflammatory cytokine signaling, the latter representing an integral part of LPL/WM pathogenesis. Personal and family history of chronic autoimmune and inflammatory conditions significantly correlate with the risk of developing LPL/WM.32,33 Development of skin lesions and LN cysts specifically in the submandibular area of MYD88L265P mice colocalize with squamous papillomas reported in AIDCre/+;Ptenlox/lox mice, suggesting that the changes are triggered by Aicda-driven activation of the transgene in non-lymphoid cells.34 Likewise, a germline-activating mutation of the MYD88 gene was recently described in a patient with skin rash, severe arthritis, and elevated serum IL-6 concentration.35 Moreover, despite the lack of lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the BM of MYD88L265P mice with LPD, MYD88L265P-driven systemic proinflammatory signaling may mediate remodeling of the BM niche, leading to increased numbers of T cells and mast cells. Notably, clonal expansion of cytotoxic T cells was reported in blood samples from LPL/WM patients36 and could contribute to better clinical responses of MYD88L265P patients.37 IL-6 signaling was also shown to mediate IgM secretion in WM cells.38 Altogether, these focal and systemic inflammatory changes may predispose MYD88L265P mice to develop the LPL/WM-like LPD phenotype.

Although LPL/WM and DLBCL cells harboring the MYD88L265P mutation depend on its activity,11,12 little is known about the role of MYD88L265P in tumor initiation in the context of intact tumor suppressors and no additional genetic alterations. In keeping with our results, overexpression of MYD88WT was shown to suffice for NF-κB activation.39 However, when introduced into primary mouse B cells, only MYD88L265P, but not MYD88WT, downregulates p65 (S534) phosphorylation and induces NF-κB–dependent negative feedback mechanisms.40 In contrast to prevailing assumptions, p65 (S534) phosphorylation is not required for p65 nuclear translocation.27 Moreover, its blockage was shown to increase NF-κB–dependent transcription, at least toward certain target genes.27 The biochemical properties of the MYD88L265P protein also differ from the MYD88WT protein in terms of stability41 and the tendency to promote aggregation into complexes resembling myddosome/My-T-BCR.13,14 The molecular differences between MYD88L265P and MYD88WT are consistent with the remarkably diverse phenotypic properties of MYD88 variants and suggest that MYD88L265P-driven activity may well extend beyond the canonical MYD88 pathway.

In line with our findings, it was recently reported that a knockin mouse model carrying the endogenous mouse Myd88L252P mutation developed LPD and DLBCL at a low frequency with considerably long latency.15 However, the in vivo oncogenic activity of human and mouse MYD88 mutations seem to differ, which expands the knowledge about this highly recurrent mutation. The LPL/WM-like features of human MYD88L265P LPD are not evident for the mouse Myd88L252P LPD phenotype. Moreover, the mouse Myd88L252P LPD had a high proliferation rate similar to that of DLBCL, contrary to human MYD88L265P LPD, which was consistent with the low-grade LPL/WM-like phenotype. In contrast to our and others’ results,40 the published knockin Myd88L252P model documented increased p65 (S534) phosphorylation, although it should be noted that these results were obtained in mouse embryonic fibroblasts rather than in B cells and thus may not be physiologically relevant or comparable to our results. No inflammatory changes were reported when expression of the mutant Myd88L252P gene was induced by AIDCre. Moreover, DLBCL cells in the mouse Myd88L252P model were BCL6–, especially when the animals were crossed with BCL2-overexpressing mice. This suggests that these lymphomas developed independently of LPD, because transformed human DLBCLs derived from LPL/WM, in contrast to de novo ABC DLBCLs, are generally BCL6+.18,19 In a different study, it was reported that BCL2+/−IL6+/−AID−/− mice develop an LPD-mimicking LPL/WM; however, the disease was also polyclonal and transcriptionally resembled chronic lymphocytic leukemia more than WM.42 Moreover, IgM expression was artificially induced in this model by knocking out both alleles of AID, an enzyme that plays crucial roles in class-switching but is unaltered in tumor cells from LPL/WM patients.42 Even though these models provide new insight into the pathogenesis of LPL/WM and DLBCL, a bona fide and clinically relevant murine model of human LPL/WM does not yet seem to exist.

The non-clonal nature of the human MYD88L265P-induced LPD, together with the acquisition of spontaneous secondary DLBCL-characteristic genetic lesions during clonal transformation to DLBCL, suggest that cooperating genetic alterations are required for MYD88L265P-driven malignant transformation. Identification of such lesions, which may not be essential for normal cell survival, could facilitate therapeutic targeting of synthetic lethal interactions in MYD88L265P-driven neoplasms, necessitated by inferior prognosis of DLBCL-transformed LPL/WM patients compared with de novo DLBCLs.43 Thus, our model seems suitable for studying molecular pathogenesis of LPL/WM by crossing with animals bearing other mutations identified by our and by others’ genomic analyses.5,6,44 Accordingly, almost all MYD88L265P LPL/WM patients show chromosome 6q14.1-6q27 deletions or CXCR4 mutations.45 Notably, both events are rare in MYD88WT patients and result in downregulation of MYD88L265P-induced tumor suppressor signaling.45,46 In C5/MCD DLBCL, clonal MYD88L265P mutations are associated with activating mutations of CD79B, which encodes a component of the BCR.5,6 Expansion of mouse GC B cells in a germ-free environment indicates that human MYD88L265P may promote selection for self-antigens and thus activation of BCR signaling, which is dysregulated in both LPL/WM and DLBCL.5,47 Importantly, engagement of the BCR upregulates Pim1 levels,48 whose locus is frequently altered in C5/MCD cases6 and during transformation from LPL/WM to DLBCL.49 Pim1 kinase activates NF-κB signaling, enhances B-cell lymphomagenesis in vivo, and was shown to be a promising therapeutic target in ABC DLBCLs.50-53 Of note, the C5/MCD subtype has the highest rate of aberrant somatic hypermutation compared with other DLBCLs.5 Therefore, expression of a single human MYD88L265P mutation (an early clonal event in human C5/MCD DLBCL) in activated mouse B cells induces selective pressure on secondary signaling and genomic alterations resembling human DLBCL pathogenesis.

Although its relatively long latency still precludes the use of our model for preclinical drug testing, the availability of this human transgene should facilitate the screening of MYD88-targeted therapeutics once a more rapidly tumorigenic model is created by genetic engineering. Moreover, MYD88WT mice can serve to differentially screen for drugs that bind with greater specificity to the mutant protein, thereby enabling identification of less toxic compounds. In summary, human MYD88L265P in transgenic mice promotes the development of a premalignant, non-lonal LPL/WM-like LPD with potential to transform to DLBCL in aged mice by acquiring secondary cooperating genetic alterations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Clyde Bongo and Madison L. O’Donnell of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) Molecular Pathology Core Laboratory for help with imaging analyses, and members of the DFCI Flow Cytometry Core for assistance with cell sorting.

This work was supported by research grants from the Leukemia Lymphoma Society, the International Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia Foundation, the Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia Foundation of Canada, and a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (R01CA196783).

Authorship

Contribution: T.S., G.Y., S.P.T., and R.D.C. designed the research; T.S., M.L.G., K.A., P.S.D., K.W., Y.H., H.T., M.J., A.K., A.D., N.A.P., A.N., and M.G.D. performed the research; V.S., G.S.P., P.J., N.C.M., and S.P.T. contributed vital new agents or analytical tools; T.S., M.L.G., G.Y., Z.R.H., and R.D.C. analyzed data; and T.S. and R.D.C. wrote the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Steven P. Treon, Bing Center for Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: steven_treon@dfci.harvard.edu; and Ruben D. Carrasco, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: ruben_carrasco@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

T.S. and M.L.G. contributed equally to this study.

SRA accession number is PRJNA560216, and the records can be found under https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA560216.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Generation and validation of conditional hMYD88(L265P)LSLtransgenic mouse model. (A) Schematic representation of the targeting vector integration site downstream of the mouse Col1A1 gene that supports high transgene expression in a variety of cell types including B cells. WT or L265P-mutated human MYD88 complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences were cloned into the targeting vector downstream of the loxP-flanked stop cassette (LSL) and electroporated together with an Flp recombinase-expressing plasmid into the C2 mouse embryonic stem cell line. C2 cells are engineered to acquire hygromycin resistance after targeted integration of the gene of interest at flippase recognition target (frt) sites. (B) Sanger sequencing of the human MYD88 sequence amplified from splenic genomic DNA isolated from transgenic mice. The presence of T>C transition results in the L265P mutation in MYD88L265P mice. (C) AIDCre-induced deletion of the LSL cassette assessed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers indicated as arrows in panel A in FACS splenic T cells and GC B cells from MYD88WT (n = 3) and MYD88L265P (n = 3) mice immunized with sheep red blood cells (SRBCs). loxP-flanked sequence: 640 bp; deleted: 330 bp. (D) Immunoblot analysis of MYD88 protein expression and p65 (S534) phosphorylation in FACS splenic GC B cells from AIDCre (n = 2), MYD88WT (n = 2), and MYD88L265P (n = 2) mice immunized with SRBCs relative to actin. (E) Immunohistochemical analysis of MYD88 expression within GCs of AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice. GCs were identified based on morphology and the presence of apoptotic bodies as well as Ki-67 staining in serial consecutive sections. Note punctate, cytoplasmic MYD88 staining in the MYD88L265P (white arrowheads) but not MYD88WT or AIDCre mice. Scale bars, 20 µm (see also supplemental Figure 1A). (F) Immunofluorescence analysis of p65 (white) subcellular localization within GC B cells (peanut agglutinin [PNA]; green) in spleens from AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice immunized with SRBCs (top and middle). Lower-magnification images (×40) were quantified using ImageJ (bottom). Gates were set up to quantify voxels with high intensity of p65 and low intensity of PNA staining or high intensity of PNA and low intensity of p65 staining. The numbers represent mean intensity of voxels within the gated region, which is proportional to the number of events gated. Note increased nuclear p65 staining (quantified as voxels positive for p65 and negative for PNA, which stain cell membrane) in the MYD88WT and MYD88L265P but not AIDCre mice. Scale bars, 20 µm (see also supplemental Figure 1B-C). (G) Spleen weights in 8- to 16-week-old AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice (n = 3 per group). Graphs depict the mean ± standard deviation (SD). P values were calculated by using Welch’s t test (left). Representative gross pictures of spleens (Sp) and LNs are shown on the right. Scale bars, 1 cm. Histologic (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E]) and IHC stains of indicated cell markers on consecutive serial sections from spleens (H) and BMs (I) from representative 8- to 16-week-old AIDCre, MYD88WT, and MYD88L265P mice. B220, B cells; CD3, T cells; CD138, plasma cells. Scale bars: white, 100 µm; black, 25 µm. pA, polyadenylation sequences; CAG, cytomegalovirus enhancer/chicken β-actin promoter; PGK ATGfrt, phosphoglycerate kinase 1 promoter followed by ATG initiation codon restoring hygromycin resistance gene expression.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/3/21/10.1182_bloodadvances.2019000588/5/m_advancesadv2019000588f1.png?Expires=1767808830&Signature=3GhGtm-gFKzgBboOIkUPaH3Awf~pK1NTm56HUsuUHqUVTWmfydIh7ftqKvgr-Fseh1~OjrM1NP7dWnaTvFq04H9pZekWk~QFF3G-~ob9QqyVQaQmnI17KrlUVsoyd6KlrAjKSTsQ8Ku0i4eqn2DEBwICG8-Oz91UAFSRCCgcvKkQXnEaTDcqFCtAZPpyiRkehEDrcrGUPQr5x6pN6O~44VMYiTQxVZRu1wc81esFJc1tgPqST1cdgw2T9VEzeZxbgWHRfsconc4k4q1L322xLIwIPFW32vcogoicCpJ8N-8kVeau7SzUHnyqXK6hIbXwz-Fc5ITQL4CNWh1GLN0SKg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)