Key Points

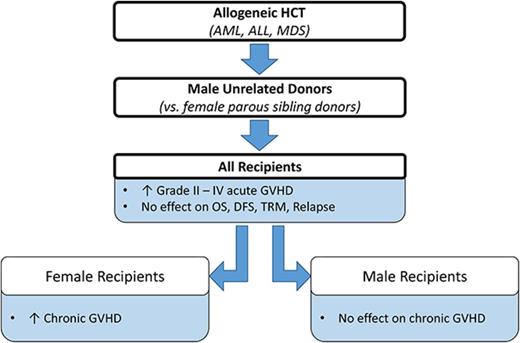

Compared with parous female sibling donors, male URDs confer more aGVHD in all patients and more cGVHD in females.

There was no difference in survival, relapse, or transplant mortality between recipients of parous female sibling or male URD grafts.

Abstract

Optimal donor selection is critical for successful allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Donor sex and parity are well-established risk factors for graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), with male donors typically associated with lower rates of GVHD. Well-matched unrelated donors (URDs) have also been associated with increased risks of GVHD as compared with matched sibling donors. These observations raise the question of whether male URDs would lead to more (or less) favorable transplant outcomes as compared with parous female sibling donors. We used the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research registry to complete a retrospective cohort study in adults with acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome, who underwent T-cell replete HCT from these 2 donor types (parous female sibling or male URD) between 2000 and 2012. Primary outcomes included grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD (aGVHD), chronic GVHD (cGVHD), and overall survival. Secondary outcomes included disease-free survival, transplant-related mortality, and relapse. In 2813 recipients, patients receiving male URD transplants (n = 1921) had 1.6 times higher risk of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD (P < .0001). For cGVHD, recipient sex was a significant factor, so donor/recipient pairs were evaluated. Female recipients of male URD grafts had a higher risk of cGVHD than those receiving parous female sibling grafts (relative risk [RR] = 1.43, P < .0001), whereas male recipients had similar rates of cGVHD regardless of donor type (RR = 1.09, P = .23). Donor type did not significantly affect any other end point. We conclude that when available, parous female siblings are preferred over male URDs.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) is a potentially curative but risky therapy for patients with hematologic malignancies. Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD and cGVHD, respectively) are significant contributors to adverse outcomes including death. To reduce complications from HCT, optimal donor selection is critical. Specific factors influencing donor selection include HLA matching, cytomegalovirus (CMV) serologic status, ABO compatibility, age, sex, and parity (ie, the number of prior pregnancies).1-3 With increasing use of unrelated donors (URDs) for allogeneic HCT, large studies have evaluated outcomes for patients with sibling donor vs URD, with most demonstrating similar long-term survival among the 2 donor groups.4-14 However, when given the option of a sibling donor or URD, sibling donors are typically preferred for convenience and possibly to reduce GVHD and to improve survival. Both donor-recipient sex mismatching and the effect of donor parity have been evaluated as possible influences on transplant morbidity and mortality. There is an increased risk of cGVHD (and in some studies, aGVHD) in recipients of grafts from female donors, regardless of recipient sex, although some studies indicate an even greater risk in male recipients, presumably because of female donors’ immune response to the H-Y antigen.2-3,15-23 Female donors who have a history of pregnancy (“parous females”), may confer more GVHD in all patients2,19,21 or, in some studies, only in male recipients.3,15-16,18,23 In 2006, a large registry analysis using the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) evaluated the impact of sex and parity on aGVHD and cGVHD after HLA-identical sibling HCT. This study established parity as a risk factor for cGVHD in both male and female recipients from parous female (vs male) sibling donors. It also demonstrated that nulliparous female sibling donors confer an increased risk of cGVHD to male recipients.21

Cost and delay are important considerations when choosing a donor, and often transplant physicians choose sibling donors regardless of sex or parity because of these concerns. However, all patients who may be transplant candidates are now urged to have HLA typing performed and siblings typed as early as possible in the treatment course. Hence, we anticipate that delays may become shorter or less frequently encountered when using URDs. Furthermore, we hypothesized that if it were shown that recipients of male URD grafts had substantially better outcomes, a clinician may decide that some additional cost and/or delay might be worthwhile. Given the well-documented increased risk of aGVHD and cGVHD associated with parous female sibling donors, we sought to understand whether choosing a male URD would be a preferred strategy for donor selection.

Methods

Data source

The data source for the study was the registry of the CIBMTR, a collaboration between the National Marrow Donor Program and the Medical College of Wisconsin: a voluntary working group of >500 transplantation centers that collaborates to share patient data and conduct scientific studies. The quality and compliance of data submission are monitored by computerized checks for errors, physician reviews, and on-site audits. Observational studies conducted by CIBMTR are performed with informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations as determined by the National Marrow Donor Program and Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional review board.

Patient selection

Adult patients who reported to the CIBMTR with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and who underwent a T-cell replete myeloablative, nonmyeloablative, or reduced intensity conditioning HCT from an HLA-identical parous female sibling or matched male URD between 2000 and 2012 were included in the study. URD HLA match was defined as a high-resolution match at HLA-A, B, C, and DRB1 as previously described.24 Donor parity was captured on CIBMTR collection forms prior to HCT. Patients were at least 25 years old at the time of transplant to allow a greater likelihood that sibling donors had the opportunity to be parous and to reduce the likelihood of missing parity status in donors of younger ages. Recipients of both peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) and bone marrow (BM) grafts were included.

Study design and end points

This was a retrospective cohort study examining outcomes among patients who received HCTs from parous female sibling donors compared with male URDs. The primary outcomes were incidence of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD, cGVHD, and overall survival (OS). aGVHD was present if graded 2 to 4 by cumulative incidence reported at 30, 60, and 100 days after transplantation.25 cGVHD was reported as cumulative incidence at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after transplantation.26-27 The competing risk for aGVHD and cGVHD was death without GVHD. Patients were censored at date of subsequent transplant or date of last follow-up. OS was defined as time to death from any cause, with censoring at last follow-up.

Secondary end points included disease-free survival (DFS), transplant-related mortality (TRM), and relapse. DFS was defined as time to treatment failure (death or relapse). TRM was defined as any death within 28 days after transplantation or death in continuous remission, analyzed with relapse as a competing risk. Relapse was reported as cumulative incidence with TRM as a competing risk.

Statistical analysis

Univariable analysis.

Donor, recipient, disease, and transplant-related factors were compared between parous female sibling and male URDs using the χ2 test for categorical variables, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables, with statistical significance set at P < .01 because of multiple comparisons. OS and DFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Incidence of aGVHD, cGVHD, TRM, and relapse were estimated using cumulative incidence models with competing risks. Variables included the main effect of donor type (parous female sibling vs male URD), as well as other donor-related variables (age, ABO match, CMV serology). Additional variables included those that were patient related (age, sex, race, Karnofsky performance status); disease-related (disease type, disease stage at time of transplant); and transplant-related (time from diagnosis to transplant, graft source, conditioning regimen, GVHD prophylaxis, year of transplant). Disease stage was defined as early (first complete remission for AML and ALL; refractory anemia [RA] or RA with ringed sideroblasts or pretransplant BM blasts <5% for MDS), intermediate (second or greater complete remission for AML and ALL), or advanced (relapsed, primary refractory disease for AML and ALL; RA with excess blasts, or BM blasts ≥5% for MDS). There were no interactions between donor type and any covariables.

Multivariable analysis.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was used to control for potentially confounding clinical variables. Each variable was tested for the proportional hazard assumption. If the assumption was violated, the variable was included as a time-dependent variable. We assessed the significance of donor type (parous female sibling and male URD) on aGVHD, cGVHD, OS, DFS, TRM, and relapse by forcing this variable into the models. To identify significant risk factors, stepwise forward selection with a threshold of P = .01 was used for entry and retention in the model. Interactions were tested between the donor type and other significant covariables, and no interactions were identified. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for the analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

We identified 2813 patients in the CIBMTR registry who met the inclusion criteria and had complete information on donor sex and parity (parous female sibling donor = 892, male URD = 1921). Race categories are reported to the CIBMTR as white, African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, other, or missing. There were small numbers of African American (2%), Asian/Pacific-Islander (4%), and other/missing (4%), so these were pooled into a single, nonwhite group. All male URDs were high-resolution matched at HLA-A, B, C, and DRB1, and the majority were also matched at HLA-DQB1 (89%), but mismatched for HLA-DPB1 (64%).

There was no difference in median age between the 2 recipient cohorts, although a smaller proportion of parous female sibling recipients were >60 years (14% vs 21%). Donor age was higher in the parous female sibling group (48 vs 32 years, P < .001). There were significantly more PBSC grafts in the parous female sibling group (87% vs 76%, P < .001). A majority of patients were transplanted with early stage disease. The median time from diagnosis to transplant differed between the 2 groups (parous female sibling: 5 months, male URD: 7 months; P < .001). Median follow-up of survivors was 66 months (range 3-170) for parous female sibling recipients and 72 months (range 3-169) for male URD recipients, P < .001 (Tables 1-3).

Recipient characteristics

| Variable . | Parous sibling . | Male URD . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 892 | 1921 | |

| Age at transplant, median (range), y | 49 (25-76) | 50 (25-75) | .15 |

| Age at transplant, n (%), y | <.001 | ||

| 25-39 | 202 (23) | 484 (25) | |

| 40-49 | 264 (30) | 464 (24) | |

| 50-59 | 297 (33) | 566 (29) | |

| ≥60 | 129 (14) | 407 (21) | |

| Sex, n (%) | .07 | ||

| Male | 481 (54) | 1107 (58) | |

| Female | 411 (46) | 814 (42) | |

| Race, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| White | 742 (83) | 1795 (93) | |

| Nonwhite | 131 (15) | 98 (5) | |

| Missing | 19 (2) | 28 (1) | |

| Karnofsky score prior to HCT (%) | .73 | ||

| <90% | 304 (34) | 631 (33) | |

| ≥90% | 563 (63) | 1138 (59) | |

| Missing | 25 (3) | 152 (8) | |

| Disease, n (%) | .94 | ||

| AML | 553 (62) | 1184 (62) | |

| ALL | 160 (18) | 341 (18) | |

| MDS | 179 (20) | 396 (21) | |

| Disease status at HCT, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Early | 540 (60) | 1000 (52) | |

| Intermediate | 116 (13) | 357 (19) | |

| Advanced | 228 (26) | 553 (29) | |

| Missing | 8 (<1) | 11 (<1) |

| Variable . | Parous sibling . | Male URD . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 892 | 1921 | |

| Age at transplant, median (range), y | 49 (25-76) | 50 (25-75) | .15 |

| Age at transplant, n (%), y | <.001 | ||

| 25-39 | 202 (23) | 484 (25) | |

| 40-49 | 264 (30) | 464 (24) | |

| 50-59 | 297 (33) | 566 (29) | |

| ≥60 | 129 (14) | 407 (21) | |

| Sex, n (%) | .07 | ||

| Male | 481 (54) | 1107 (58) | |

| Female | 411 (46) | 814 (42) | |

| Race, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| White | 742 (83) | 1795 (93) | |

| Nonwhite | 131 (15) | 98 (5) | |

| Missing | 19 (2) | 28 (1) | |

| Karnofsky score prior to HCT (%) | .73 | ||

| <90% | 304 (34) | 631 (33) | |

| ≥90% | 563 (63) | 1138 (59) | |

| Missing | 25 (3) | 152 (8) | |

| Disease, n (%) | .94 | ||

| AML | 553 (62) | 1184 (62) | |

| ALL | 160 (18) | 341 (18) | |

| MDS | 179 (20) | 396 (21) | |

| Disease status at HCT, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Early | 540 (60) | 1000 (52) | |

| Intermediate | 116 (13) | 357 (19) | |

| Advanced | 228 (26) | 553 (29) | |

| Missing | 8 (<1) | 11 (<1) |

Donor characteristics

| Variable . | Parous sibling . | Male URD . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor age, median (range), y | 48 (3-82) | 32 (18-61) | <.001 |

| Donor age, n (%), y | <.001 | ||

| 18-19 | 1 (<1) | 52 (3) | |

| 20-29 | 35 (4) | 750 (39) | |

| 30-39 | 180 (20) | 651 (34) | |

| 40-49 | 284 (32) | 380 (20) | |

| 50-59 | 252 (28) | 83 (4) | |

| ≥60 | 136 (15) | 2 (<1) | |

| Missing | 4 (<1) | 3 (<1) | |

| D/R CMV serologic status, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| −/− | 149 (17) | 605 (31) | |

| −/+ | 157 (18) | 713 (37) | |

| +/− | 122 (14) | 158 (8) | |

| +/+ | 439 (49) | 365 (19) | |

| Missing | 25 (3) | 80 (4) | |

| D/R ABO match, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Matched | 580 (65) | 859 (45) | |

| Minor mismatch | 128 (14) | 459 (24) | |

| Major mismatch | 135 (15) | 450 (23) | |

| Bidirectional mismatch | 40 (4) | 147 (8) | |

| Missing | 9 (1) | 6 (<1) | |

| Number of prior pregnancies in female donors, n (%) | N/A | ||

| 1 | 137 (15) | 0 | |

| 2 | 277 (31) | 0 | |

| 3 | 185 (21) | 0 | |

| ≥4 | 175 (20) | 0 | |

| Missing | 118 (13) | 0 | |

| Variable . | Parous sibling . | Male URD . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor age, median (range), y | 48 (3-82) | 32 (18-61) | <.001 |

| Donor age, n (%), y | <.001 | ||

| 18-19 | 1 (<1) | 52 (3) | |

| 20-29 | 35 (4) | 750 (39) | |

| 30-39 | 180 (20) | 651 (34) | |

| 40-49 | 284 (32) | 380 (20) | |

| 50-59 | 252 (28) | 83 (4) | |

| ≥60 | 136 (15) | 2 (<1) | |

| Missing | 4 (<1) | 3 (<1) | |

| D/R CMV serologic status, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| −/− | 149 (17) | 605 (31) | |

| −/+ | 157 (18) | 713 (37) | |

| +/− | 122 (14) | 158 (8) | |

| +/+ | 439 (49) | 365 (19) | |

| Missing | 25 (3) | 80 (4) | |

| D/R ABO match, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Matched | 580 (65) | 859 (45) | |

| Minor mismatch | 128 (14) | 459 (24) | |

| Major mismatch | 135 (15) | 450 (23) | |

| Bidirectional mismatch | 40 (4) | 147 (8) | |

| Missing | 9 (1) | 6 (<1) | |

| Number of prior pregnancies in female donors, n (%) | N/A | ||

| 1 | 137 (15) | 0 | |

| 2 | 277 (31) | 0 | |

| 3 | 185 (21) | 0 | |

| ≥4 | 175 (20) | 0 | |

| Missing | 118 (13) | 0 | |

D/R, donor/recipient; N/A, not applicable.

HCT characteristics

| Variable . | Parous sibling . | Male URD . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, median (range), mo | 5 (<1-153) | 7 (<1-291) | <.001 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, n (%), mo | <.001 | ||

| <6 | 492 (55) | 821 (43) | |

| 6-12 | 197 (22) | 522 (27) | |

| >12 | 203 (23) | 574 (30) | |

| Missing | 0 | 4 (<1) | |

| Graft type, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| BM | 118 (13) | 462 (24) | |

| Peripheral blood | 774 (87) | 1459 (76) | |

| Conditioning regimen intensity, n (%) | .38 | ||

| Myeloablative | 673 (75) | 1403 (73) | |

| TBI | 341 (51) | 685 (49) | |

| No TBI | 332 (49) | 718 (51) | |

| Reduced intensity | 165 (18) | 385 (20) | |

| TBI | 31 (19) | 67 (17) | |

| No TBI | 134 (81) | 318 (83) | |

| Nonmyeloablative | 54 (6) | 133 (7) | |

| TBI | 51 (95) | 122 (92) | |

| No TBI | 3 (5) | 11 (8) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Tac + MTX | 266 (30) | 834 (43) | |

| Tac + MTX + others | 29 (3) | 176 (9) | |

| Tac ± others | 121 (14) | 365 (19) | |

| CsA + MTX | 310 (35) | 278 (14) | |

| CsA ± others | 128 (14) | 191 (10) | |

| Others* | 36 (4) | 76 (4) | |

| Missing | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | |

| Year of transplant, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| 2000-2003 | 255 (29) | 317 (17) | |

| 2004-2008 | 375 (42) | 1119 (58) | |

| 2009-2012 | 262 (29) | 485 (25) | |

| Variable . | Parous sibling . | Male URD . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, median (range), mo | 5 (<1-153) | 7 (<1-291) | <.001 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, n (%), mo | <.001 | ||

| <6 | 492 (55) | 821 (43) | |

| 6-12 | 197 (22) | 522 (27) | |

| >12 | 203 (23) | 574 (30) | |

| Missing | 0 | 4 (<1) | |

| Graft type, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| BM | 118 (13) | 462 (24) | |

| Peripheral blood | 774 (87) | 1459 (76) | |

| Conditioning regimen intensity, n (%) | .38 | ||

| Myeloablative | 673 (75) | 1403 (73) | |

| TBI | 341 (51) | 685 (49) | |

| No TBI | 332 (49) | 718 (51) | |

| Reduced intensity | 165 (18) | 385 (20) | |

| TBI | 31 (19) | 67 (17) | |

| No TBI | 134 (81) | 318 (83) | |

| Nonmyeloablative | 54 (6) | 133 (7) | |

| TBI | 51 (95) | 122 (92) | |

| No TBI | 3 (5) | 11 (8) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Tac + MTX | 266 (30) | 834 (43) | |

| Tac + MTX + others | 29 (3) | 176 (9) | |

| Tac ± others | 121 (14) | 365 (19) | |

| CsA + MTX | 310 (35) | 278 (14) | |

| CsA ± others | 128 (14) | 191 (10) | |

| Others* | 36 (4) | 76 (4) | |

| Missing | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | |

| Year of transplant, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| 2000-2003 | 255 (29) | 317 (17) | |

| 2004-2008 | 375 (42) | 1119 (58) | |

| 2009-2012 | 262 (29) | 485 (25) | |

CsA, cyclosporine; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; Tac, tacrolimus; TBI, total body irradiation.

Tac + CsA + MTX (n = 32), posttransplant cyclophosphamide (n = 25), Tac + CsA + MTX + MMF (n = 13), Tac + CsA + MMF (n = 12), Tac + CsA + MTX + others (n = 6), Tac + CsA + MMF + others (n = 2), Tac + CsA + others (n = 7), MTX + others (n = 5), MTX (n = 2), MMF (n = 3), MMF + others (n = 3), Siro (n = 1), steroids (n = 1).

aGVHD

There was an increased risk of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD in recipients of male URD grafts as compared with recipients of parous female sibling donor grafts (100-day grade 2-4 aGVHD 46% in patients receiving male URD grafts vs 35% in those receiving parous female sibling grafts). This finding persisted in multivariable analysis (relative risk [RR] = 1.56, P < .0001) (Figure 1). Other significant covariables associated with grade 2 to 4 aGVHD included GVHD prophylaxis (tacrolimus/methotrexate lowest risk, P = .0019) and graft source (PBSC higher risk, RR = 1.32, P = .0003). Recipients of male URD grafts may also have experienced a higher risk of grade 3 to 4 aGVHD as compared with recipients of parous female sibling donor grafts, but this finding did not reach statistical significance given our conservative P value cutoff (RR = 1.27, P = .016) (Table 4).

GVHD outcomes

| . | aGVHD 2-4 . | aGVHD 3-4 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aGVHD variable . | n . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . | n . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . |

| Donor group (main effect) | ||||||||

| Parous sibling | 880 | 1.00 | 880 | 1.00 | ||||

| Male unrelated | 1908 | 1.56 | 1.31-1.85 | <.0001 | 1908 | 1.27 | 0.98-1.64 | .016 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | .002 | .0002 | ||||||

| Tac + MTX | 1094 | 1.00 | 1094 | 1.00 | ||||

| Tac + MTX + others | 202 | 1.12 | 0.65-1.18 | .258 | 202 | 1.12 | 0.72-1.74 | .502 |

| Tac ± others | 480 | 1.11 | 0.84-1.28 | .632 | 480 | 1.11 | 0.80-1.53 | .410 |

| CsA + MTX | 583 | 0.92 | 0.80-1.23 | .960 | 583 | 0.92 | 0.66-1.28 | .500 |

| CsA ± others | 315 | 1.75 | 1.09-1.72 | .0001 | 315 | 1.75 | 1.26-2.43 | <.0001 |

| Others | 112 | 1.20 | 0.91-1.86 | .062 | 112 | 1.20 | 0.69-2.10 | .389 |

| Graft source | ||||||||

| BM | 578 | 1.00 | – | – | – | – | ||

| PB | 2213 | 1.32 | 1.08-1.61 | .0003 | – | – | – | – |

| . | aGVHD 2-4 . | aGVHD 3-4 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aGVHD variable . | n . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . | n . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . |

| Donor group (main effect) | ||||||||

| Parous sibling | 880 | 1.00 | 880 | 1.00 | ||||

| Male unrelated | 1908 | 1.56 | 1.31-1.85 | <.0001 | 1908 | 1.27 | 0.98-1.64 | .016 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | .002 | .0002 | ||||||

| Tac + MTX | 1094 | 1.00 | 1094 | 1.00 | ||||

| Tac + MTX + others | 202 | 1.12 | 0.65-1.18 | .258 | 202 | 1.12 | 0.72-1.74 | .502 |

| Tac ± others | 480 | 1.11 | 0.84-1.28 | .632 | 480 | 1.11 | 0.80-1.53 | .410 |

| CsA + MTX | 583 | 0.92 | 0.80-1.23 | .960 | 583 | 0.92 | 0.66-1.28 | .500 |

| CsA ± others | 315 | 1.75 | 1.09-1.72 | .0001 | 315 | 1.75 | 1.26-2.43 | <.0001 |

| Others | 112 | 1.20 | 0.91-1.86 | .062 | 112 | 1.20 | 0.69-2.10 | .389 |

| Graft source | ||||||||

| BM | 578 | 1.00 | – | – | – | – | ||

| PB | 2213 | 1.32 | 1.08-1.61 | .0003 | – | – | – | – |

| All donor/recipient pairs . | Male recipients only . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cGVHD variable . | n . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . | n . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . |

| Donor/recipient pair (main effect) | <.0001 | |||||||

| Parous sibling to female | 405 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Parous sibling to male | 474 | 1.39 | 1.09-1.78 | .001 | 474 | 1.00 | ||

| Male unrelated to female | 799 | 1.43 | 1.14-1.80 | <.0001 | ||||

| Male unrelated to male | 1099 | 1.52 | 1.22-1.89 | <.0001 | 1099 | 1.09 | 0.90-1.32 | .231 |

| Year of transplant | .002 | ns | ||||||

| 2000-2003 | 564 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 2004-2008 | 1471 | 1.06 | 0.88-1.29 | .381 | ||||

| 2009-2012 | 742 | 0.86 | 0.70-1.06 | .064 | ||||

| Graft source | ||||||||

| BM | 574 | 1 | 327 | 1.00 | ||||

| PB | 2203 | 1.73 | 1.43-2.08 | <.0001 | 1246 | 1.56 | 1.23-2.08 | <.0001 |

| All donor/recipient pairs . | Male recipients only . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cGVHD variable . | n . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . | n . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . |

| Donor/recipient pair (main effect) | <.0001 | |||||||

| Parous sibling to female | 405 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Parous sibling to male | 474 | 1.39 | 1.09-1.78 | .001 | 474 | 1.00 | ||

| Male unrelated to female | 799 | 1.43 | 1.14-1.80 | <.0001 | ||||

| Male unrelated to male | 1099 | 1.52 | 1.22-1.89 | <.0001 | 1099 | 1.09 | 0.90-1.32 | .231 |

| Year of transplant | .002 | ns | ||||||

| 2000-2003 | 564 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 2004-2008 | 1471 | 1.06 | 0.88-1.29 | .381 | ||||

| 2009-2012 | 742 | 0.86 | 0.70-1.06 | .064 | ||||

| Graft source | ||||||||

| BM | 574 | 1 | 327 | 1.00 | ||||

| PB | 2203 | 1.73 | 1.43-2.08 | <.0001 | 1246 | 1.56 | 1.23-2.08 | <.0001 |

CI, confidence interval; parous sibling, parous sibling donor; PB, peripheral blood; ns, not significant.

cGVHD

At 6 months and 1 year posttransplantation, there was no difference in incidence of cGVHD among male URD recipients (33% and 50%, respectively) as compared with parous female sibling recipients (30% and 50%, respectively). We found that recipient sex was a significant covariable in the cGVHD multivariable model, so this model was adjusted to include a combination of donor type and recipient sex as the main effect. For male recipients, the risk of cGVHD was similar between donor types (34% for each donor type, P = .89 at 6 months, and 55% for parous female sibling donor vs 51% for male URDs, P = .09 at 12 months; RR = 1.09, P = .23). However, female recipients receiving male URD grafts experienced higher risks of cGVHD at 6 months posttransplant (31% as compared with 24% in female recipients receiving parous female sibling donor grafts, P = .01). By 1 year posttransplant, this difference was no longer statistically significant (50% of females receiving male URD grafts experienced cGVHD as compared with 44% of females receiving parous female sibling grafts, P = .07). In multivariable analysis, for female patients, male URDs conferred an adjusted relative risk of cGVHD of 1.43 (P < .0001) compared with those receiving parous female sibling grafts. Other significant covariables included year of transplant, with cGVHD more frequently seen in earlier transplant years (overall P = .002), and receipt of peripheral blood grafts (RR = 1.73 compared with BM, P < .0001) (Table 4). In male patients, donor type did not significantly impact cGVHD (Figure 2).

Cumulative incidence of cGVHD by donor type and recipient sex. (A) Male recipients. (B) Female recipients.

Cumulative incidence of cGVHD by donor type and recipient sex. (A) Male recipients. (B) Female recipients.

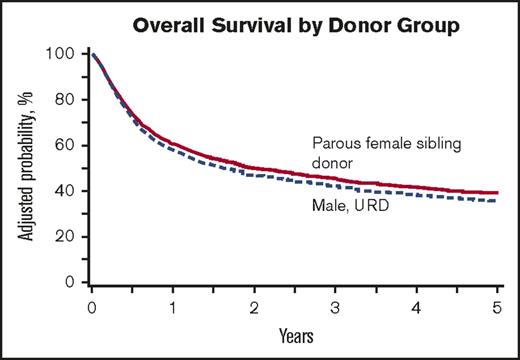

OS

A smaller percentage of male URD recipients were alive at 100 days (82% vs 88% of recipients of parous female sibling transplants, P < .001). However, by 1 year, this difference disappeared (Figure 3). In multivariable analysis, this small decrement in OS in recipients of male URD donor grafts persisted, although it no longer reached statistical significance (male URD RR = 1.10; 99% CI, 0.99-1.26; P = .07). Other variables associated with poorer OS included older age, poorer Karnofsky score, advanced disease status at transplant, and earlier year of transplant (Table 5). Cause of death was largely because of primary disease and was similar between the 2 groups (parous female sibling 41%, male URD 44%). Six percent of deaths in both the parous female sibling and male URD groups were attributable to aGVHD. A comparable incidence of death attributed to cGVHD was seen in the 2 groups.

Cox regression for OS

| Variable . | N . | HR . | 99% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor group (main effect) | ||||

| Parous sibling | 892 | 1.00 | ||

| Male unrelated | 1921 | 1.10 | 0.96-1.26 | .070 |

| Age at transplant, y | <.0001 | |||

| 25-39 (ref) | 686 | 1.00 | ||

| 40-49 | 728 | 1.20 | 1.00-1.43 | .010 |

| 50-59 | 863 | 1.43 | 1.21-1.70 | <.0001 |

| 60+ | 536 | 1.61 | 1.33-1.95 | <.0001 |

| Karnofsky score at transplant | <.0001 | |||

| ≥90 (ref) | 1701 | 1.00 | ||

| <90 | 935 | 1.36 | 1.20-1.55 | <.0001 |

| Missing | 177 | 1.03 | 0.81-1.33 | .724 |

| Disease status at transplant | <.0001 | |||

| Early (ref) | 1540 | 1.00 | ||

| Intermediate | 473 | 1.11 | 0.93-1.32 | .119 |

| Advanced | 781 | 1.82 | 1.59-2.08 | <.0001 |

| Missing | 19 | 1.90 | 0.99-3.66 | .011 |

| Year of transplant | <.0001 | |||

| 2000-2003 (ref) | 572 | 1.00 | ||

| 2004-2008 | 1494 | 0.96 | 0.82-1.13 | .523 |

| 2009-2012 | 747 | 0.76 | 0.63-0.92 | <.001 |

| Variable . | N . | HR . | 99% CI . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor group (main effect) | ||||

| Parous sibling | 892 | 1.00 | ||

| Male unrelated | 1921 | 1.10 | 0.96-1.26 | .070 |

| Age at transplant, y | <.0001 | |||

| 25-39 (ref) | 686 | 1.00 | ||

| 40-49 | 728 | 1.20 | 1.00-1.43 | .010 |

| 50-59 | 863 | 1.43 | 1.21-1.70 | <.0001 |

| 60+ | 536 | 1.61 | 1.33-1.95 | <.0001 |

| Karnofsky score at transplant | <.0001 | |||

| ≥90 (ref) | 1701 | 1.00 | ||

| <90 | 935 | 1.36 | 1.20-1.55 | <.0001 |

| Missing | 177 | 1.03 | 0.81-1.33 | .724 |

| Disease status at transplant | <.0001 | |||

| Early (ref) | 1540 | 1.00 | ||

| Intermediate | 473 | 1.11 | 0.93-1.32 | .119 |

| Advanced | 781 | 1.82 | 1.59-2.08 | <.0001 |

| Missing | 19 | 1.90 | 0.99-3.66 | .011 |

| Year of transplant | <.0001 | |||

| 2000-2003 (ref) | 572 | 1.00 | ||

| 2004-2008 | 1494 | 0.96 | 0.82-1.13 | .523 |

| 2009-2012 | 747 | 0.76 | 0.63-0.92 | <.001 |

HR, hazard ratio; ref, reference value.

Secondary end points

DFS.

DFS was inferior in the male URD cohort at 100 days (male URD 73% vs parous female sibling 78%, P = .003) and at 6 months (60% vs 65%, respectively, P = .008) posttransplantation. At 1 year and beyond, however, there was no significant difference in DFS: 1-year male URD 49% vs parous female sibling 54% (P = .03), 2-year male URD 41% vs parous female sibling 44% (P = .19), 3-year male URD 37% vs parous female sibling 39% (P = .49), and 5-year male URD 33% vs parous sibling 34% (P = .52). In multivariable analysis, donor type was not associated with DFS (P = .449). Older patient age, poorer Karnofsky score, TBI-based conditioning, advanced disease, longer time from diagnosis to transplant, and earlier year of transplant were associated with poorer DFS (Table 6).

Multivariable analyses for DFS, TRM, and relapse

| . | DFS . | TRM . | Relapse . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | N . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . |

| Donor group (main effect) | ||||||||||

| Parous sibling (ref) | 852 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Male URD | 1901 | 1.04 | 0.91-1.19 | .449 | 1.07 | 0.88-1.31 | .380 | 1.03 | 0.87-1.23 | .610 |

| Age at transplant, y | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||||||

| 25-39 (ref) | 669 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 40-49 | 710 | 1.17 | 0.98-1.40 | .022 | 1.32 | 1.01-1.74 | .009 | 1.09 | 0.86-1.37 | .360 |

| 50-59 | 848 | 1.39 | 1.170-1.64 | <.0001 | 1.67 | 1.29-2.17 | <.0001 | 1.27 | 1.02-1.58 | .006 |

| 60+ | 526 | 1.66 | 1.37-2.00 | <.0001 | 2.05 | 1.53-2.75 | <.0001 | 1.53 | 1.19-1.96 | <.0001 |

| Disease | <.0001 | |||||||||

| AML (ref) | 1701 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | ||

| ALL | 490 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.97 | 0.77-1.21 | .708 |

| MDS | 562 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.62 | 0.49-0.77 | <.0001 |

| Karnofsky score at transplant | <.0001 | |||||||||

| ≥90 (ref) | 1662 | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | – | – | ||||

| <90 | 917 | 1.31 | 1.15-1.48 | <.0001 | 1.59 | 1.31-1.92 | <.0001 | – | – | – |

| Missing | 174 | 1.10 | 0.86-1.41 | .308 | 1.11 | 0.75-1.63 | .487 | – | – | – |

| TBI used in conditioning regimen | ||||||||||

| TBI ± others (ref) | 1277 | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | – | – | ||||

| Non-TBI | 1476 | 0.86 | 0.76-0.97 | .002 | 0.83 | 0.69-0.99 | .008 | – | – | – |

| Disease status at transplant | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Early (ref) | 1509 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | ||||

| Intermediate | 466 | 1.06 | 0.890-1.26 | .407 | – | – | – | 1.12 | 0.89-1.42 | .198 |

| Advanced | 760 | 1.87 | 1.63-2.14 | <.0001 | – | – | – | 2.57 | 2.15-3.06 | <.0001 |

| Missing | 18 | 1.81 | 0.92-3.56 | .023 | – | – | – | 2.73 | 1.24-6.02 | .001 |

| Year of transplant | .005 | .002 | ||||||||

| 2000-2003 (ref) | 544 | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | – | – | ||||

| 2004-2008 | 1464 | 0.96 | 0.82-1.13 | .534 | 0.85 | 0.68-1.08 | .077 | – | – | – |

| 2009-2012 | 745 | 0.82 | 0.68-0.98 | .004 | 0.68 | 0.52-0.90 | <.001 | – | – | – |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, mo | .0054 | |||||||||

| <6 (ref) | 1286 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | ||

| 6-12 | 702 | – | – | – | 1.35 | 1.08-1.68 | .0004 | – | – | – |

| >12 | 761 | – | – | – | 1.10 | 0.88-1.37 | .2842 | – | – | – |

| Missing | 4 | – | – | – | 1.44 | 0.11-19 | .7165 | – | – | – |

| . | DFS . | TRM . | Relapse . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable . | N . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . | RR . | 99% CI . | P . |

| Donor group (main effect) | ||||||||||

| Parous sibling (ref) | 852 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Male URD | 1901 | 1.04 | 0.91-1.19 | .449 | 1.07 | 0.88-1.31 | .380 | 1.03 | 0.87-1.23 | .610 |

| Age at transplant, y | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |||||||

| 25-39 (ref) | 669 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 40-49 | 710 | 1.17 | 0.98-1.40 | .022 | 1.32 | 1.01-1.74 | .009 | 1.09 | 0.86-1.37 | .360 |

| 50-59 | 848 | 1.39 | 1.170-1.64 | <.0001 | 1.67 | 1.29-2.17 | <.0001 | 1.27 | 1.02-1.58 | .006 |

| 60+ | 526 | 1.66 | 1.37-2.00 | <.0001 | 2.05 | 1.53-2.75 | <.0001 | 1.53 | 1.19-1.96 | <.0001 |

| Disease | <.0001 | |||||||||

| AML (ref) | 1701 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | ||

| ALL | 490 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.97 | 0.77-1.21 | .708 |

| MDS | 562 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.62 | 0.49-0.77 | <.0001 |

| Karnofsky score at transplant | <.0001 | |||||||||

| ≥90 (ref) | 1662 | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | – | – | ||||

| <90 | 917 | 1.31 | 1.15-1.48 | <.0001 | 1.59 | 1.31-1.92 | <.0001 | – | – | – |

| Missing | 174 | 1.10 | 0.86-1.41 | .308 | 1.11 | 0.75-1.63 | .487 | – | – | – |

| TBI used in conditioning regimen | ||||||||||

| TBI ± others (ref) | 1277 | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | – | – | ||||

| Non-TBI | 1476 | 0.86 | 0.76-0.97 | .002 | 0.83 | 0.69-0.99 | .008 | – | – | – |

| Disease status at transplant | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Early (ref) | 1509 | 1.00 | – | – | – | 1.00 | ||||

| Intermediate | 466 | 1.06 | 0.890-1.26 | .407 | – | – | – | 1.12 | 0.89-1.42 | .198 |

| Advanced | 760 | 1.87 | 1.63-2.14 | <.0001 | – | – | – | 2.57 | 2.15-3.06 | <.0001 |

| Missing | 18 | 1.81 | 0.92-3.56 | .023 | – | – | – | 2.73 | 1.24-6.02 | .001 |

| Year of transplant | .005 | .002 | ||||||||

| 2000-2003 (ref) | 544 | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | – | – | ||||

| 2004-2008 | 1464 | 0.96 | 0.82-1.13 | .534 | 0.85 | 0.68-1.08 | .077 | – | – | – |

| 2009-2012 | 745 | 0.82 | 0.68-0.98 | .004 | 0.68 | 0.52-0.90 | <.001 | – | – | – |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, mo | .0054 | |||||||||

| <6 (ref) | 1286 | – | – | – | 1.00 | – | – | – | ||

| 6-12 | 702 | – | – | – | 1.35 | 1.08-1.68 | .0004 | – | – | – |

| >12 | 761 | – | – | – | 1.10 | 0.88-1.37 | .2842 | – | – | – |

| Missing | 4 | – | – | – | 1.44 | 0.11-19 | .7165 | – | – | – |

Relapse.

There was no significant difference in incidence of relapse between the 2 donor cohorts at any time posttransplantation (P = .59). The increased risk of GVHD was not offset by lower relapse rate: in multivariable analysis, the relative risk of relapse in male URD recipients was 1.03 (P = .61). Significant variables associated with relapse included older age of the patient, AML diagnosis (vs MDS), and advanced disease status (Table 6).

TRM.

TRM was greater in recipients of male URD grafts at 100 days (11% vs 8%, P = .003). However, at 6 months and beyond, incidence of TRM was not significantly different between the 2 cohorts. In multivariable analysis, donor type was not significantly predictive of TRM, but older age, poorer Karnofsky score, TBI-based conditioning, and earlier year of transplant were associated with higher TRM (Table 6).

Discussion

We undertook this analysis to provide guidance to transplant clinicians when the only available sibling donor is a sister with previous pregnancies, as these donors are known to confer an increased risk of aGVHD and cGVHD when compared with male siblings. We sought to answer the question, would unrelated male donors be preferable to parous female siblings? We found that after adjusting for other significant covariables, recipients of male URD grafts experienced a 56% higher risk of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD compared with recipients of parous female sibling grafts. Although parous female siblings more frequently donated PBSC, a product known to increase cGVHD, the effect was preserved even when controlling for this variable.28 When evaluating only the most severe aGVHD (grade 3 to 4) this increased risk may have persisted, but our results no longer demonstrated statistical significance, possibly because of a relatively low incidence of severe aGVHD in the study sample. The increased early TRM in the male URD group may be attributable in part to the higher incidence of aGVHD. However, over time, TRM and OS were not significantly impacted by donor source in our multivariable analyses, suggesting that the impact of aGVHD on these outcomes occurs early posttransplantation and may be counterbalanced by other factors posttransplant.

In contrast to aGVHD, the incidence of cGVHD varied not just by donor type, but also by sex of the recipient. We found that male recipients had equivalent rates of cGVHD regardless of donor type, whereas female recipients fared better with parous female sibling donors. Although prior work has focused on cGVHD in male recipients of female donor grafts, as female T cells recognize Y-chromosome encoded male-specific minor histocompatibility (H-Y) antigens,29-30 this study suggests that other minor histocompatibility antigen mismatches may be more important than H-Y mismatch. Why this effect was seen only in female recipients is unclear.

OS did not appear to be better among recipients of male URD grafts, possibly because TRM from cGVHD may have offset other benefits. Although some prior studies in URDs have found no association between parity and OS,24 others have demonstrated poorer OS (and higher TRM) in male recipients of female grafts,31 and yet other analyses have shown improved OS.32 It is difficult to reconcile the marked differences in survival outcomes in the many studies that have evaluated donor sex or parity, but our large study suggests that if parity is a risk factor for GVHD or other poor outcomes, it is not as significant as the effects of receiving a graft from a URD. Like most transplant analyses, we confirmed that older patient age, poorer patient performance status, advanced disease, and earlier year of transplant were associated with poorer OS.2

We acknowledge limitations in our study. As with all registry studies, there may be miscategorization of the incidence of GVHD. Although we have information on degree of HLA match, this did not include data on killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) gene complexes, which may affect early relapse and mortality.33 Furthermore, we did not control for permissive and nonpermissive mismatching at DQB1 and DP. We did not evaluate the use of donor leukocyte infusions for relapsed disease in our analysis, which could impact the incidence of aGVHD and cGVHD, as well as relapse and OS. Our analysis was restricted to T-cell replete transplants, and hence our findings may not be extrapolated to patients receiving in vivo or ex vivo T-cell-depleted transplants. This is particularly relevant given our primary end points of aGVHD and cGVHD.34-35 Finally, as in all studies analyzing donor parity, we recognize that documentation of parity may be unreliable and subject to misclassification bias. However, if a nulliparous female donor were miscategorized as parous, we expect that this would bias the results toward the null.

In conclusion, compared with parous female sibling donors, male URDs imparted an increased risk of grade 2 to 4 aGVHD to all recipients, an increased risk of cGVHD to female recipients, and an equivalent risk of cGVHD to male recipients. This finding suggests that other minor histocompatibility antigen mismatches outweigh the impact of H-Y mismatch. Donor type does not impact long-term OS. When faced with a choice of an unrelated male donor or a parous female sibling donor, physicians should favor HLA-identical sibling donors irrespective of donor sex and parity in order to reduce the risk of aGVHD and cGVHD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the CIBMTR for data collection and analysis.

The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health; a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 4U10HL069294 from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; a contract (HHSH250201200016C) with Health Resources and Services Administration/Department of Health and Human Services; 2 grants (N00014-17-1-2388 and N00014-16-1-2020) from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from (asterisk indicates corporate members) *Actinium Pharmaceuticals Inc., *Amgen Inc., *Amneal Biosciences, *Angiocrine Bioscience Inc., an anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin, Astellas Pharma US, Atara Biotherapeutics Inc., Be the Match Foundation, *Bluebird Bio Inc., *Bristol Myers Squibb Oncology, *Celgene Corporation, Cerus Corporation, *Chimerix Inc., Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Gamida Cell Ltd., Gilead Sciences Inc., HistoGenetics Inc., Immucor, *Incyte Corporation, Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC, *Jazz Pharmaceuticals Inc., Juno Therapeutics, Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., Kite Pharma Inc., Medac GmbH, MedImmune, The Medical College of Wisconsin, *Merck & Co Inc., *Mesoblast, MesoScale Diagnostics Inc., Millennium (the Takeda Oncology Co.), *Miltenyi Biotec Inc., National Marrow Donor Program, *Neovii Biotech NA Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. – Japan, PCORI, *Pfizer Inc., *Pharmacyclics LLC, PIRCHE AG, *Sanofi Genzyme, *Seattle Genetics, Shire, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals Inc., St. Baldrick’s Foundation, *Sunesis Pharmaceuticals Inc., Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Inc., Takeda Oncology, Telomere Diagnostics Inc., and University of Minnesota.

The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, the Health Resources and Services Administration, or any other agency of the US government.

Authorship

Contribution: A.J.K., S.K., M.T.H., M.A., S.R.S., and A.W.L. designed research; S.K. and M.T.H. collected data and performed statistical analysis; A.J.K., S.K., M.T.H., M.A., S.R.S., and A.W.L. interpreted data; A.J.K. drafted the manuscript; and S.K., M.T.H., M.A., S.R.S., J.A.P., D.R.C., A.M.A., M.D.A., J.-Y.C., M.S.C., C.S.C., S.F., R.P.G., U.G., G.A.H., B.K.H., S.K.H., Y.I., R.T.K., M.A.K.-D., M.L.M., N.S.M., D.I.M., H.N., M.N., M.Q., O.R., H.C.S., K.R.S., M.M.S., T.T., A.U.-I., L.F.V., and A.W.L. critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for S.K.H. is Department of Oncology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The current affiliation for Y.I. is National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan.

The current affiliation for M.A.K.-D. is Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, FL.

Correspondence: Anita J. Kumar, Tufts Medical Center, 800 Washington St, Box #245, Boston, MA 02111; e-mail: ajkumar@alum.mit.edu.