Key Points

Cold agglutinin syndrome is one of the rare immune-related adverse events of nivolumab.

Rituximab should be considered for treatment of nivolumab-induced cold agglutinin syndrome.

Introduction

Nivolumab is a monoclonal immunoglobulin G antibody that blocks programmed death-1 and improves antitumor T cell responses. Nivolumab has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for several cancers, including metastatic melanoma, squamous non-small cell lung carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, and urothelial carcinoma.1-3 However, many immune-related adverse events (irAEs), such as rash, hypothyroidism, diarrhea, colitis, pneumonitis, and nephritis, are reported with the use of programmed death-1 inhibitors.4,5 We present a patient with an unusual irAE developed after nivolumab therapy, cold agglutinin syndrome (CAS), that was successfully treated with rituximab.

Case description

An 89-year-old white woman with a history of hypothyroidism, breast cancer, and marginal zone B cell lymphoma in complete remission was diagnosed with metastatic upper tract urothelial carcinoma. After receiving 2 cycles of chemotherapy with gemcitabine and carboplatin, computed tomography of her abdomen had shown progression of the disease, and she was started on immunotherapy with nivolumab. She received nivolumab at 6 mg/kg every 4 weeks. By the time the patient completed her seventh cycle of nivolumab, she presented to the oncology clinic for follow-up with 3 weeks of progressive fatigue, shortness of breath on exertion, decreased oral intake, and 2 pounds of weight loss. She was found to have pancytopenia that developed within the previous 4 weeks; nivolumab was held, and she was referred to the benign hematology clinic for determination of the etiology and management of the new-onset pancytopenia.

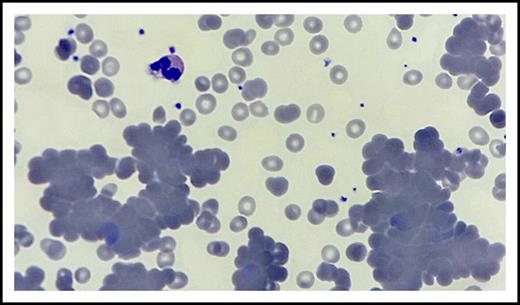

The patient presented to the benign hematology clinic after receiving 2 units of red blood cell transfusion with the improvement of her dyspnea and fatigue. Physical examination was notable for conjunctival pallor but no lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, lower extremity edema, or skin changes. Her complete blood count was significant for pancytopenia with predominant neutropenia, hemoglobin 10.5 g/dL (after transfusion and from a previous 7.8 g/dL), absolute neutrophil count 0.36 × 109/L, white blood cell count 2.1 × 109/L, platelets 124 × 109/L, mean cell volume 90 fL, red blood cell count 3.36 × 1012/L, and absolute reticulocyte count 70 560 cells per microliter. Anisocytosis, few hypochromic red blood cells, abundant microspherocytes, few nucleated red blood cells, rouleaux and agglutination formation, scattered platelet clumping, and moderate to severe neutropenia were observed on peripheral smear (Figure 1). There was no evidence of fragmented red blood cells, left shift, or circulating blasts.

Peripheral blood smear. Hematoxylin and eosin stain of peripheral blood smear (original magnification ×100) shows anisocytosis, rouleaux and agglutination formation, few hypochromic red blood cells, microspherocytes and nucleated red blood cells, scattered platelet clumping, and moderate to severe neutropenia.

Peripheral blood smear. Hematoxylin and eosin stain of peripheral blood smear (original magnification ×100) shows anisocytosis, rouleaux and agglutination formation, few hypochromic red blood cells, microspherocytes and nucleated red blood cells, scattered platelet clumping, and moderate to severe neutropenia.

Iron studies were compatible with posttransfusion effect and anemia in neoplastic disease. Further testing revealed normal thyroid-stimulating hormone, serum-free thyroxine, cobalamin, copper, and slightly elevated folate levels, which ruled out nutrient deficiencies and thyroid endocrinopathy as causes of the pancytopenia. Serum chemistry studies showed haptoglobin 41 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 739 U/L, and indirect bilirubin 1.3 mg/dL. The direct antiglobulin test was negative for immunoglobulin G but positive for anti-complement 3d. Cold agglutinin titer was positive (>64). No neutrophil-reactive antibodies were detected in the patient’s blood sample.

Methods

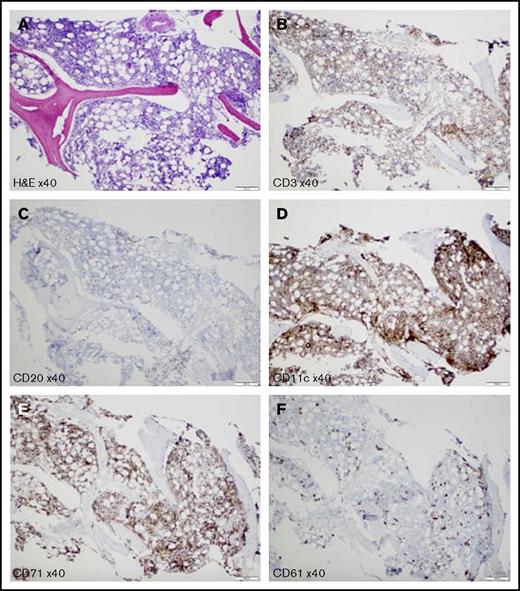

The patient was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg per day before all of the test results were finalized. However, she did not respond well to steroid therapy and was admitted after the clinic visit for further management of pancytopenia. She was diagnosed with checkpoint inhibitor therapy–induced CAS, based on direct antiglobulin test, peripheral blood smear features, bone marrow biopsy, and flow cytometry results. Bone marrow biopsy results supported the peripheral destruction of blood cells, with 80%-90% cellularity and increased elements of all 3 lineages but no evidence of myelodysplastic syndrome, lymphoma, or myelophthisic process (Figure 2). During the hospital course, she received a total of 5 units of red blood cell transfusions over a 2-week period before starting rituximab. She was started on rituximab at a fixed dose of 1000 mg every 2 weeks before discharge and completed a total of 4 doses. Eight weeks postrituximab therapy, the patient did not require additional blood product transfusions, she was asymptomatic, and her hemoglobin had recovered to 11.2 g/dL, absolute neutrophil count 1.42 × 109/L, and platelet count 161 × 109/L. Cold agglutinin was undetectable. Nivolumab was not reintroduced because she was in complete remission after 7 cycles of therapy.

Bone marrow biopsy. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain shows hypercellular for the age (80%-90%) bone marrow with increased elements of all 3 lineages. Reticulin stain shows no bone marrow fibrosis (data not shown). Anti-CD3 (B) and anti-CD20 (C) antibodies show scattered small T cells and B cells, respectively; no clusters of B cells and no large B cells are detected. (D) Anti-CD11c antibody represents increased myeloid elements. (E) Anti-CD71 antibody highlights increased erythroid elements. (F) Anti-CD61 antibody demonstrates markedly increased left-shifted megakaryocytes; no atypical megakaryocytes or megakaryocyte clustering is detected. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Bone marrow biopsy. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain shows hypercellular for the age (80%-90%) bone marrow with increased elements of all 3 lineages. Reticulin stain shows no bone marrow fibrosis (data not shown). Anti-CD3 (B) and anti-CD20 (C) antibodies show scattered small T cells and B cells, respectively; no clusters of B cells and no large B cells are detected. (D) Anti-CD11c antibody represents increased myeloid elements. (E) Anti-CD71 antibody highlights increased erythroid elements. (F) Anti-CD61 antibody demonstrates markedly increased left-shifted megakaryocytes; no atypical megakaryocytes or megakaryocyte clustering is detected. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Results and discussion

We presented a case with metastatic urothelial carcinoma refractory to doublet chemotherapy who developed CAS after 7 cycles of nivolumab therapy. There have been a few case reports in the last few years of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) that developed after nivolumab therapy in the context of various cancers, and all of them have been reported as warm or mixed AIHA.6-11 To our knowledge, this is the first case report of CAS secondary to nivolumab therapy and in the context of a urothelial carcinoma.

There were 2 other possible etiologies with this case that we need to consider before concluding that nivolumab was the cause of the CAS. There were no medications known to cause CAS on the patient’s medication list at the time of the diagnosis, and there were no changes other than nivolumab in the last year. She had been in complete remission for marginal zone B lymphoma for 9 years, and clinical and laboratory examination of the patient did not show any evidence of active disease. Additionally, there was no history of positive red blood cell alloantibodies or AIHA in the patient prior to this diagnosis. We concluded that the most likely cause of the CAS in our patient is nivolumab therapy.

Current cumulative experience from the cases that reported AIHA secondary to nivolumab shows that its development is not related to duration or the dose of the nivolumab administration and the type of primary cancer. AIHA can occur anytime from 2 to 8 cycles after the start of therapy, which should alert oncologists to monitor blood counts closely during the nivolumab treatment. It can also develop at a dose as low as 3 mg/kg every 30 days up to 6 mg/kg every 4 weeks.11 Our patient developed CAS after the seventh cycle of the treatment at the dose of 6 mg/kg every 4 weeks.

Working group guidelines are available for the management of irAEs. The consensus recommendations rely on corticosteroids and other immunomodulation strategies, and their judicious use is recommended to reduce the short- and long-term complications.12 In the reported AIHA cases secondary to nivolumab, in addition to cessation of therapy and packed red blood cell transfusion, there have been 2 approaches for the management: high-dose steroids and rituximab.9,10 Although high-dose steroids seem to be effective and adequate therapy for AIHA secondary to nivolumab, 1 patient did not respond to steroid treatment and died, and another patient partially responded to steroids and was also treated with rituximab.

In our case, we first discontinued nivolumab and started steroids. However, the patient did not respond to steroids and worsened clinically. Rituximab has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of primary cold agglutinin disease, whereas patients with cold agglutinin disease/CAS have occasionally been responsive to steroids.13-16 Indeed, our patient responded well to rituximab with the improvement of hemoglobin to baseline and undetectable cold agglutinin titers.

In conclusion, when the diagnosis of nivolumab-induced CAS is made, discontinuation of nivolumab therapy, supportive packed red blood cell transfusion, and initiation of rituximab should be the measures that need to be taken because steroids are not effective at treating CAS.

Authorship

Contribution: M.H. prepared the manuscript; S.N.K. prepared the figures; and C.M.R.H. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Merve Hasanov, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin St, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: merve.hasanov@uth.tmc.edu.