Key Points

AI reduces manual analysis time for the detection of MRD to 1 minute per case, on average.

Our simplified AI-assisted analysis has the potential to increase accessibility to MRD testing by FC.

Visual Abstract

Measurable residual disease (MRD) assessment by flow cytometry (FC) plays an essential role in prognosis and therapy escalation of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). However, the high degree of expertise and manual analysis time required limits the availability of this assay. To overcome this limitation, we developed a data-enhancing artificial intelligence (AI) pipeline that accelerates and simplifies MRD analysis. Unaltered FC files from 171 B-ALL MRD-positive and 89 MRD-negative cases were processed through an AI pipeline trained with 31 expert-gated negative controls. Cluster-informed downsampling reduced FC files from 1.2 million to 155 884 cells per case, on average, (87% cellularity reduction), whereas preserving small MRD populations (median, 100% retention for MRD of <1%) and allowing for true percentage MRD estimates using a correction factor. A deep neural network cell classifier automatically identified normal hematopoietic subsets (macro-averaged F1 score of 0.86); and an AI measure of anomaly discriminated B-ALL from benign mononuclear (area under the curve [AUC] of 0.98) or B-lymphoid cells (AUC of 0.94). Manual analysis of AI-enhanced files was completed in only 1.01 minutes per case, on average (standard deviation of ±0.57); with 100% positive agreement with conventional analysis (for MRD of ≥0.01%), 100% negative agreement, and excellent quantitative correlation (R2 = 0.92). Our cloud-based AI-enhancement solution accelerates B-ALL MRD identification without compromising test performance and has the potential of facilitating B-ALL MRD analysis by more clinical laboratories.

Introduction

Measurable residual disease (MRD) assessment is one of the most important independent prognostic factors of relapse-free survival and overall survival in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).1-4 B-ALL MRD testing is routinely used to guide treatment intensity, and has been considered as a surrogate end point to accelerate the evaluation of novel therapies in clinical trials.5 B-ALL MRD can be assessed by a variety of methodologies, including flow cytometry (FC), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of tumor-specific fusion genes, allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR of tumor-specific immunoglobulin gene (IG) rearrangements, and next-generation sequencing of rearranged IGs.6 Compared with molecular methods, FC is generally faster, less expensive, more accessible, and applicable to a higher percentage of patients. In addition, FC does not require previous knowledge of disease-specific IG sequences, fusion genes, or immunophenotypic abnormalities at diagnosis. Modern FC platforms are capable of achieving the recommended assay sensitivity of at least 0.01% (10−4), which is the risk stratification threshold reported by most studies.7 Although FC continues to be the most commonly used method for B-ALL MRD assessment, molecular methods have the advantage of detecting lower MRD levels (up to 10−6), which may have prognostic significance in some settings.8

For clinical laboratories, the main challenge of B-ALL MRD assessment by FC is the expertise and experience required to detect very small percentages of leukemic cells with highly variable immunophenotype and distinguish them from immunophenotypically complex subsets of benign B-cell precursors (hematogones). This manual and time-consuming process requires visual evaluation of numerous 2-dimensional dot plots in multiple combinations, color coding of benign subsets through sequential selection of cells on multiple plots (gating), and identification of an immature B-lymphoid population that deviates from the complex normal hematogone maturation. In addition, the large amount of data analyzed (typically 0.5-5 million cells, 8-14 parameters per cell) not only contributes to the complexity of visual evaluation but also demands a higher level of computer power and analysis software capabilities than conventional leukemia/lymphoma immunophenotyping.

To overcome these limitations, we developed a cloud-computing artificial intelligence (AI) pipeline that simplifies and accelerates the identification of B-ALL MRD without compromising test performance. This CCADDAS (clustering and classification of all events, dimensionality reduction, downsampling, and aberrancy scaling) pipeline transforms raw data files produced by the FC analyzer into markedly smaller, AI-annotated, and software-agnostic files, including a measure of aberrancy in comparison with negative controls. We tested this pipeline on a large cohort of FC data files produced from our 10-color B-ALL MRD clinical assay, and benchmarked the pipeline’s performance against conventional analysis of original FC files.

Methods

Patient and sample selection

Fresh bone marrow aspirate (258) or peripheral blood (2) specimens were received for flow cytometric analysis of B-ALL MRD at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) between January 2020 and December 2024, including 171 cases from 107 patients reported as positive for MRD (≤5%), and 89 cases from 63 patients reported as negative for MRD using conventional analysis. Cases showing MRD of >5% by conventional analysis were excluded from this study. The mean age at first analysis was 48 years (range, 8 months-88 years), and the male-to-female ratio was 1.4:1. A total of 68 patients (110 samples) had a history of B-ALL with BCR::ABL1 fusion, and 13 patients (28 samples) had a history of B-ALL with BCR::ABL1–like features. Of all MRD populations reported in 171 positive samples, 27 (16%) were negative for CD10, 21 (12%) were negative for CD34, and 3 (2%) were negative for CD19. Electronic medical records were reviewed to confirm a previous diagnosis of B-ALL. In addition, 24 bone marrow aspirate and 7 peripheral blood specimens from unique patients with no history of hematologic malignancy were studied using the B-ALL MRD panel as negative control specimens. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board.

FC

A single-tube, 10-color B-ALL MRD panel was developed and validated to a lower limit of quantification of 0.002% (2 × 10−5) using dilution studies. The panel consisted of a cocktail of fluorescently labeled antibodies recognizing CD10, CD19, CD20, CD22, CD24, CD34, CD38, CD45, CD58, and CD66 (supplemental Table 1). Fresh blood or bone marrow specimens were subjected to bulk lysis using ammonium chloride potassium lysing solution to eliminate erythrocytes. After 2 washes with phosphate-buffered saline, 2 million cells were incubated with our panel’s antibody cocktail for 15 minutes at room temperature, followed by 1 wash with phosphate-buffered saline, and acquisition of up to 1.5 million total events per sample on a FACSLyric flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Panel-specific mean fluorescence intensity target values were established using cytometer setup and tracking beads (BD Biosciences) on the BD FACSuite Clinical Application analyzer software (BD Biosciences) and standardized across 5 flow cytometers. Optimal panel-specific spillover values were defined for each cytometer. Daily quality control included automatic adjustment of photomultiplier tube voltages to match mean fluorescence intensity tube target values using cytometer setup and tracking beads. Spillover was visually evaluated during daily routine analysis to identify spillover drifts and corrected for each cytometer as needed.

CCADDAS AI pipeline

An ad hoc combined python and R script was developed and deployed on Google Vertex AI, to process ungated FC (.fcs) files using previously described machine learning algorithms for removal of acquisition errors (FlowCut),9 dimensionality reduction (uniform manifold approximation and projection [UMAP]),10 clustering (phenotyping by accelerated refined community-partitioning [PARC]),11 and single-event classification (Tensorflow and Keras12; Figure 1A). This pipeline was designed to process unaltered FC files produced by the analyzer, without requiring manual pregating to exclude debris, doublets, acquisition errors, or nonspecific staining artifacts (supplemental Figure 1A).

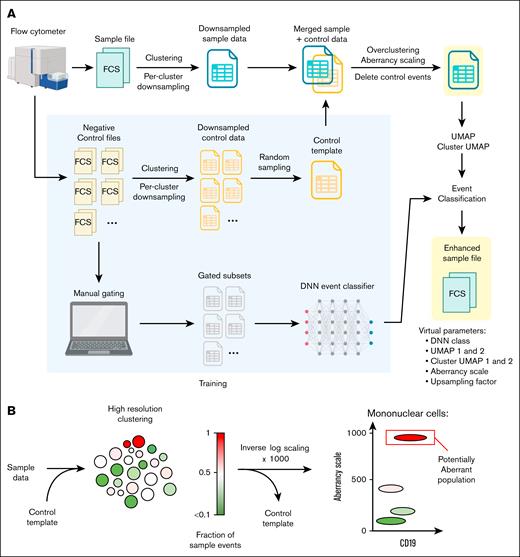

AI pipeline for FC data. (A) Pipeline scheme showing intake of unaltered FC (fcs) files produced by the analyzer, main processing steps, and AI-enhanced downsampled exports with added AI parameters. The pipeline was trained with 31 negative controls samples, which were used as a control template to measure deviation from normal, and also gated by expert analysts to train a DNN event classifier. (B) A cluster-based aberrancy scale was used to quantify deviation from normal, based on merging sample and control events, high-resolution clustering, and inverse log-scaling the fraction of sample events per cluster. FCS, fcs files.

AI pipeline for FC data. (A) Pipeline scheme showing intake of unaltered FC (fcs) files produced by the analyzer, main processing steps, and AI-enhanced downsampled exports with added AI parameters. The pipeline was trained with 31 negative controls samples, which were used as a control template to measure deviation from normal, and also gated by expert analysts to train a DNN event classifier. (B) A cluster-based aberrancy scale was used to quantify deviation from normal, based on merging sample and control events, high-resolution clustering, and inverse log-scaling the fraction of sample events per cluster. FCS, fcs files.

FlowCut was used as the first pipeline step to automatically eliminate common acquisition errors (supplemental Figure 1B). Next, the spillover matrix from the fcs file (analyzer settings) was applied. Logarithmic parameters were first ArcSin transformed, and then all parameters were scaled 0 to 1. Total events were clustered using default PARC settings (low resolution clusters), followed by per-cluster random donwsampling to a maximum of 5000 events per cluster (clusters smaller than 5000 events were not downsampled). An upsampling factor was calculated as the ratio of the number of original to downsampled events per cluster and added as a parameter to the corresponding events from each cluster. Two low-density (high minimum distance) UMAP dimensions were calculated. A 2-dimensional map of clusters (cluster UMAP) was then created by calculating the UMAP coordinates of each low-resolution cluster centroid, repulsing the coordinates to prevent overlap, and annotating each event with these repulsed coordinates.

Each downsampled file was then merged with a predefined random sample of events from similarly processed files corresponding to 31 negative control specimens. The merged file was overclustered using high-resolution PARC settings (high resolution clusters). Each event was annotated with an aberrancy scale parameter that reflected the inverse-log transformed and scaled (0-1000) fraction of sample events within that event’s corresponding high-resolution cluster (Figure 1B). Using this transformation, values >500 corresponded to >90% sample events in the high-resolution cluster. All control events were then removed.

A deep neural network (DNN) event classifier12 was trained on 14 expert-defined cell types from 31 negative control files. The model architecture consisted of an input layer accepting all light scatter and fluorescence features of our B-ALL MRD panel, 4 dense layers (including ReLU activation functions, L1L2 regularization, and batch normalization), and a softmax output layer with 14 classes (cell types). The model was trained using the Adam optimizer and categorical cross-entropy loss on a data set of 40 295 731 events, split into training (64%), validation (16%), and test (20%) sets without class weighting. This cell classifier was added to the pipeline and deployed as discrete integer values on a single added parameter (DNN class).

Pipeline exports were constructed as downsampled raw fluorescence data with intact metadata and original spillover matrix, in addition to 7 AI parameters (DNN class, UMAP 1 and 2, cluster UMAP 1 and 2, aberrancy scale, and upsampling factor) and 2 research parameters (low-resolution and high-resolution cluster assignments). Aberrancy scale, cluster UMAP, and DNN class values were dispersed using a random normal distribution to add noise and provide visibility on conventional FC dot plots.

Manual analysis of FC files

Analysis of original FC files was performed on Infinicyt version 2.0 (BD Biosciences), using traditional manual gating on multiple 2-dimensional dot plots, based on previously described strategies adapted to our panel.13

All AI-enhanced files were analyzed by 1 author (P.H.), with a second blinded review by another author (M.J.W.). For timing studies, 40 randomly selected cases were analyzed using both AI-enhanced files (P.H. and M.J.W.), and conventional analysis of original files (M.J.W. and M.M.T.), with a 2-week washout period between analysis methods.

Statistical analysis

Mean ranks of aberrancy scale values between MRD-positive and MRD-negative cases, and manual analysis times between AI-enhanced files and conventional analysis of original files were compared using the Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test. Events per file and file size comparisons were performed using the paired t test. Percentages of retained events after downsampling were studies using the unpaired t test. MRD percentages between 2 methods were compared using simple linear regression. The performance of fluorescent and AI parameters to identify MRD was studied using receiver operating characteristics curves based on 2000 randomly selected events per group (MRD events from positive cases, and mononuclear or B-lymphoid events from negative cases). The performance of the AI cell classifier was studied using F1 scores. All statistical analyses and non-FC data plots were performed using Graph-Pad Prism, version 10.3.1 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For illustration purposes only (not part of the analysis workflow), total or gated events from analyzed pipeline exports were merged, downsampled to a maximum of 25 000 events per DNN class, and studied on conventional UMAP embeddings using FCS Express, version 7.22.0031 (De Novo Software, Pasadena, CA).

Results

Cluster-informed downsampling preserves MRD events

We developed a data processing pipeline to simplify the flow cytometric analysis of B-ALL MRD and tested this solution on raw FC data from 260 samples (153 patients) received in our practice for B-ALL MRD analysis by FC. Our pipeline included a downsampling step aimed to remove redundant events while preserving immunophenotypically distinct minute subsets including MRD populations. This cluster-informed downsampling strategy reduced the number of events per case from 1.2 million to 155 884 cells, on average (87% cellularity reduction, P < .0001), which is similar to the number of events studied in routine leukemia/lymphoma immunophenotyping (100 000-200 000 events).14 The overall file size was also markedly reduced from 64.5 megabytes to 13.7 megabytes, on average (79% data reduction, P < .0001; Figure 2A), eliminating the need for specialized software or enhanced computing power for manual analysis of MRD data.

Cluster-informed downsampling preserves MRD. (A) Extent of downsampling of B-ALL MRD files after processing through our pipeline, based on number of events per file (top) and file size (bottom). Bars and whiskers show means and SDs, respectively. (B) Effect of cluster-informed downsampling on total (blue), MRD (red), and benign (gray) absolute number of events detected on pipeline exports, relative to true number of events (estimated per upsampling factor correction). Data are plotted by level of MRD involvement or by specific DNN class. Bars and whiskers show means and SDs, respectively. (C) Actual percentage of MRD events detected on downsampled pipeline exports (no upsampling factor correction), compared with MRD percentages on the corresponding original files. PCs, plasma cells; PDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cells.

Cluster-informed downsampling preserves MRD. (A) Extent of downsampling of B-ALL MRD files after processing through our pipeline, based on number of events per file (top) and file size (bottom). Bars and whiskers show means and SDs, respectively. (B) Effect of cluster-informed downsampling on total (blue), MRD (red), and benign (gray) absolute number of events detected on pipeline exports, relative to true number of events (estimated per upsampling factor correction). Data are plotted by level of MRD involvement or by specific DNN class. Bars and whiskers show means and SDs, respectively. (C) Actual percentage of MRD events detected on downsampled pipeline exports (no upsampling factor correction), compared with MRD percentages on the corresponding original files. PCs, plasma cells; PDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cells.

All (139) cases reported as positive above the recommended assay sensitivity (≥0.01%) showed detectable MRD subsets on analysis of downsampled pipeline exports (100% positive agreement with conventional analysis for MRD of ≥0.01%). In these cases, the pipeline’s downsampling algorithm adequately preserved small MRD subsets (98.01%-100% MRD event preservation for MRD subsets of <1000 cells on the original file). Larger MRD populations were downsampled proportionally to their size but always yielding easily detectable subsets (minimum: 931 events; Figure 2B). Because downsampling almost exclusively affected background benign subsets, the relative frequency of MRD events on pipeline exports was markedly increased (9.82-times higher, on average, for cases with <1% MRD events), resulting in easier visual MRD identification during analysis (Figure 2C). No MRD subsets were identified on downsampled analysis of exports from 89 negative cases (100% negative agreement with conventional analysis).

AI automatically identifies normal hematopoietic subsets

To eliminate the time-consuming expert gating of benign subsets and B-cell maturation stages needed for B-ALL MRD analysis, we trained a DNN cell classifier using 31 negative controls gated by expert analysts. This classifier demonstrated robust performance across most cell populations (macro-averaged F1 score, 0.86), except for the rare and poorly defined CD24− hematogone subset (F1 score, 0.25; Figure 3A). Of note, 86% of misclassified CD24− hematogone events (false positives plus false negatives) remained within a hematogone category (supplemental Figure 2), and this minor classification variability did not affect visual interpretation of B-cell maturation patterns on sample specimens (Figure 3B).

Automated identification of benign hematopoietic subsets highlights B-cell maturation stages, which are distinct from leukemic cells. (A) Performance of a DNN cell classifier included in our pipeline, shown as F1 scores for each cell class. (B) Automated classification of events from MRD-negative cases (merged pipeline exports), showing accurately depicted B-cell maturation stages (arrows), and DNN-classes matching clustered events on an unsupervised UMAP projection of all cases. (C) Merged leukemic events from MRD-positive exports (red), compared with MRD-negative exports (black); showing extensive overlap on 2-dimensional plots, high immunophenotypic variability of MRD, and clear MRD segregation from normal events on a UMAP projection. FSC-A, forward scatter amplitude; PDCs, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; SSC-A, side scatter amplitude.

Automated identification of benign hematopoietic subsets highlights B-cell maturation stages, which are distinct from leukemic cells. (A) Performance of a DNN cell classifier included in our pipeline, shown as F1 scores for each cell class. (B) Automated classification of events from MRD-negative cases (merged pipeline exports), showing accurately depicted B-cell maturation stages (arrows), and DNN-classes matching clustered events on an unsupervised UMAP projection of all cases. (C) Merged leukemic events from MRD-positive exports (red), compared with MRD-negative exports (black); showing extensive overlap on 2-dimensional plots, high immunophenotypic variability of MRD, and clear MRD segregation from normal events on a UMAP projection. FSC-A, forward scatter amplitude; PDCs, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; SSC-A, side scatter amplitude.

A quantitative measure of aberrancy simplifies MRD detection

The immunophenotype of B-ALL MRD is highly variable and extensively overlaps with normal B-cell maturation on all conventional 2-dimensional plots, and on simple linear dimensionality reduction (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 3). However, a clear divergence of leukemic cells from normal B-cell maturation can be demonstrated on a nonlinear dimensionality reduction (UMAP) plot when considering all antigens simultaneously (Figure 3C). To simplify the identification of subsets that diverge from normal based on all antigens, our pipeline included a quantitative cluster-based anomaly estimate relative to negative controls (aberrancy scale). Almost all (97%) MRD subsets from positive cases were rapidly identified on a single plot by exploring a limited number of mononuclear subsets with aberrancy scale values of >500 (>90% sample representation compared with controls; Figure 4; supplemental Figure 4). After this initial step, some cases (30%) benefited from a better delineation of the neoplastic population using a single cluster-UMAP gate instead (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 4B). Only 6 positive cases (3%) showed MRD subsets with aberrancy scale values of <500, 5 of which were positive below the recommended assay sensitivity of 0.01%.8 These rare, minute MRD subsets were easily identified on maturation dot plots generated by automated identification of benign subsets (supplemental Figure 4A).

Examples of AI-assisted MRD analyses. Pipeline exports were analyzed using a conventional FC software. Events were automatically classified and color-coded based on DNN class parameter values, corresponding to CD19− hematogones (gold), early hematogones (green), late hematogones (orange), mature B-cells (violet), and others. True MRD percentages (red boxes) were estimated on downsampled exports using the upsampling factor parameter and simple mathematical operations. (A) Typical MRD population with abnormal bright CD10 expression and loss of CD38, rapidly identified using a single gate on an aberrancy scale vs CD19 dot plot. (B) Less frequent MRD immunophenotype showing bright CD66c expression as the only detectable abnormality, also easily identified using the aberrancy scale parameter. (C) B-ALL MRD with unusual immunophenotypic features (abnormal dim to negative CD45 expression and negativity for CD34), easily identified based on high aberrancy scale values but more accurately delineated using a cluster UMAP gate. (D) Challenging B-ALL MRD population in a patient with a history of anti-CD19 (blinatumomab) and anti-CD20 (rituximab) therapies, showing partial dim expression of CD22 as the only detectable B-lineage antigen (negative for CD10, CD19, CD20, and CD24). This subset was easily identified using a single gate on high aberrancy scale values. SSC-A, side scatter amplitude.

Examples of AI-assisted MRD analyses. Pipeline exports were analyzed using a conventional FC software. Events were automatically classified and color-coded based on DNN class parameter values, corresponding to CD19− hematogones (gold), early hematogones (green), late hematogones (orange), mature B-cells (violet), and others. True MRD percentages (red boxes) were estimated on downsampled exports using the upsampling factor parameter and simple mathematical operations. (A) Typical MRD population with abnormal bright CD10 expression and loss of CD38, rapidly identified using a single gate on an aberrancy scale vs CD19 dot plot. (B) Less frequent MRD immunophenotype showing bright CD66c expression as the only detectable abnormality, also easily identified using the aberrancy scale parameter. (C) B-ALL MRD with unusual immunophenotypic features (abnormal dim to negative CD45 expression and negativity for CD34), easily identified based on high aberrancy scale values but more accurately delineated using a cluster UMAP gate. (D) Challenging B-ALL MRD population in a patient with a history of anti-CD19 (blinatumomab) and anti-CD20 (rituximab) therapies, showing partial dim expression of CD22 as the only detectable B-lineage antigen (negative for CD10, CD19, CD20, and CD24). This subset was easily identified using a single gate on high aberrancy scale values. SSC-A, side scatter amplitude.

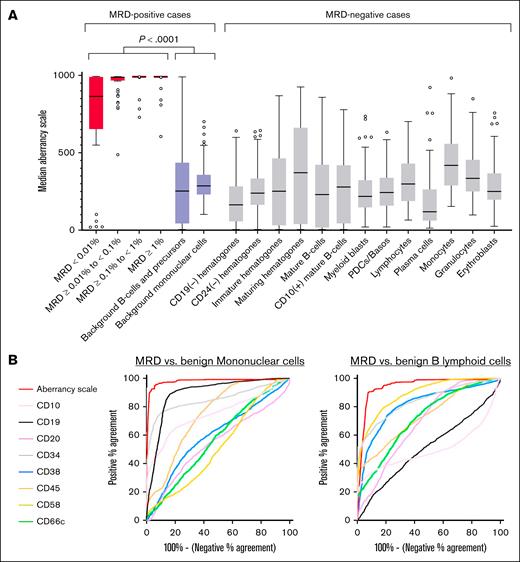

Overall, aberrancy scale values of MRD subsets were significantly higher (median, 911) than values of background benign B-lymphoid cells (median, 379; P < .0001) and total background mononuclear cells (median, 486; P < .0001; Figure 5A). The contribution of each antigen for the identification of MRD depended on the comparison group studied (benign B-lymphoid cells vs mononuclear cells), as quantified based on individual discriminatory values for CD20 (area under the curves: 0.54 and 0.69), CD38 (0.60 and 0.81), CD45 (0.75 and 0.74), CD58 (0.52 and 0.89), and CD66c (0.56 and 0.72, respectively). As expected, the calculated aberrancy scale showed superior performance (area under the curves: 0.98 and 0.94, respectively) by integrating the discriminatory features of all antigens into a single parameter for an expedited manual analysis (Figure 5B).

A single anomaly metric accelerates the identification of MRD. (A) Median aberrancy scale values of B-ALL MRD subsets identified on pipeline exports (red boxes), plotted by level of MRD involvement. Also shown are median aberrancy scale values for background B-lineage cells and mononuclear cells from MRD-positive cases (purple boxes), in addition to DNN-defined subsets from MRD-negative cases (light gray boxes). Lines depict median of medians, boxes represent the interquartile range, and whiskers extend to the most extreme data point within 1.5 times the interquartile range (Tukey test). Outliers are shown as circles. (B) Receiver operating characteristic curves for classification of mononuclear events (left) or B-lymphoid events (right) as B-ALL MRD, showing the performance of the computed aberrancy scale parameter, compared to native immunophenotypic properties.

A single anomaly metric accelerates the identification of MRD. (A) Median aberrancy scale values of B-ALL MRD subsets identified on pipeline exports (red boxes), plotted by level of MRD involvement. Also shown are median aberrancy scale values for background B-lineage cells and mononuclear cells from MRD-positive cases (purple boxes), in addition to DNN-defined subsets from MRD-negative cases (light gray boxes). Lines depict median of medians, boxes represent the interquartile range, and whiskers extend to the most extreme data point within 1.5 times the interquartile range (Tukey test). Outliers are shown as circles. (B) Receiver operating characteristic curves for classification of mononuclear events (left) or B-lymphoid events (right) as B-ALL MRD, showing the performance of the computed aberrancy scale parameter, compared to native immunophenotypic properties.

Optimal performance of AI-assisted MRD analysis

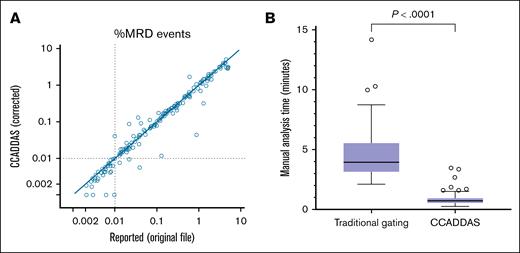

True percentage of MRD events were accurately estimated using the upsampling factor parameter, showing excellent quantitative correlation with values reported by conventional analysis of the original files (linear regression slope, 1.18; intercept, 0.04%; R2 = 0.92; P < .0001; Figure 6A). Of 32 cases reported as positive below the 0.01% recommended sensitivity threshold, 28 cases were also interpreted as positive by analysis of downsampled pipeline exports (88% positive agreement with conventional analysis for MRD of <0.01%). In these cases, MRD events detectable on export files were adequately preserved after downsampling (98% MRD event preservation, on average; Figure 2B).

Optimal performance of AI-assisted MRD testing. (A) MRD percentages resulted by analyzing CCADDAS pipeline exports (after upsampling factor correction), compared with those reported by conventional analysis of original files (positive cases only). (B) Expert manual analysis time using traditional gating of original files, compared with accelerated analysis using CCADDAS pipeline exports.

Optimal performance of AI-assisted MRD testing. (A) MRD percentages resulted by analyzing CCADDAS pipeline exports (after upsampling factor correction), compared with those reported by conventional analysis of original files (positive cases only). (B) Expert manual analysis time using traditional gating of original files, compared with accelerated analysis using CCADDAS pipeline exports.

Manual analysis time of pipeline exports on a random sample of 60 cases was 1.01 minutes, on average (standard deviation [SD] of 0.62), as performed by 2 investigators. In contrast, the expected manual analysis time of original files in our clinical laboratory is 14.16 minutes, on average (SD of 3.71), based on a previous study of 36 random cases gated initially by a frontline technologist and then regated by an expert analyst (current clinical workflow, data not shown). On a separate random cohort with equal representation of negative (n = 10), low-positive (n = 10: 0.01%-0.1%), mid-positive (n = 10: 0.1%-1%), and high positive (n = 10: 1%-5% MRD) cases, average manual analysis time by 2 highly trained experts was 0.86 minutes on average for pipeline exports (SD of 0.57), and 4.85 minutes on average (SD of 2.58) for conventional analysis of original files (82% reduction in analysis time, P < .0001; Figure 6B).

Discussion

B-ALL MRD detection by FC is based on the identification of immature B-lymphoid subsets that are not present in normal or reactive settings (different than normal). We hereby demonstrate that a single AI feature depicting deviation from normal can accelerate the identification of MRD subsets independent of immunophenotypic variability. This calculated parameter (aberrancy scale) required only 31 negative controls (no positive samples needed for training) and facilitated the rapid identification of MRD events using a single gate and dot plot in 97% of cases. Indeed, this discriminatory capacity would make a strong case for broad clinical application if exhibited by a commercially available reagent. In our model, inclusion of posttherapy samples did not improve the performance of the aberrancy scale (data not shown), as therapy-induced changes do not result in the appearance of immunophenotypically distinct subsets not represented in control samples (supplemental Figure 5).

Our proposed pipeline efficiently eliminates redundant events while preserving MRD populations, resulting in a markedly reduced file that is similar in size to that of routine leukemia/lymphoma immunophenotyping (155 884 cells on average, 87% cellularity reduction) and amenable to any analysis strategy, software, or computing power used in conventional FC. Given our selective downsampling strategy, the relative frequency of low-level MRD (<1%) was almost 10-times higher on our pipeline exports than original files, facilitating visual identification of small neoplastic subsets. For any gated subset, the number of events on the original file can be easily estimated by multiplying the number for events on the downsampled file times the average of the downsampling factor parameter for that gate; a mathematical operation easily performed on any conventional FC software. Using this strategy, we showed that accurate MRD quantitation can be achieved on our downsampled files.

Our DNN classifier eliminated the need for time-consuming identification of benign populations and B-cell maturation stages required for MRD analysis. This classifier was deployed as a single added parameter to our pipeline exports, suitable for automatic gating and coloring of benign subsets using templated fixed gates on any FC analysis software. Overall, our AI-assisted B-ALL MRD analysis strategy required only about 1 minute of manual analysis time per case, on average, compared with 14 minutes of conventional analysis time in our current practice (including gating by frontline technologists and review by expert analysts) and 5 minutes of analysis time on average when conventional analysis was performed entirely by an expert. This translates into at least 83% technologist full-time equivalent savings. Additional potential benefits include easier training of frontline technologists on this simplified analysis, and faster second review with only few editable gates.

Few studies have previously evaluated the utility of machine learning in the flow cytometric assessment of B-ALL MRD. Dimensionality reduction strategies on gated B lymphoid subsets have been attempted to separate benign B lymphoid cells from MRD events using principal component analysys,13 t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding,15 or radar plots.16 Unfortunately, trained dimensionality reduction embeddings are not designed to perform outside immunophenotypic MRD variants present on training cohorts, whereas the location of MRD events on dimensionality reduction plots cannot be predicted when using untrained sample-specific embeddings. On a small cohort, a support vector machine classifier trained on individual diagnostic samples was able to detect MRD on corresponding follow-up samples from the same patient, but this strategy does not take into account immunophenotypic drifting and is not practical to implement.17 Cell classifiers using Gaussian mixture models18 or a neural network based on the transformer architecture19 both showed good performance to detect B-ALL MRD of >0.05% when trained with positive samples (22 or 65 samples, respectively), but these approaches provided no clear path to achieve greater sensitivity or implement clinically. More recently, the Euroflow Consortium tested a trained classifier of benign subsets for their standardized B-ALL MRD panel, which included an unclassifiable event category to highlight possible MRD events.20 Despite some similarities to our approach, this algorithm was restricted to a specific analysis software and had minimal impact on overall manual analysis time (10-15 minutes using the classifier, compared with 15-20 minutes without).

At least 4 different consensus panels have been described for the detection of B-ALL MRD by FC (Euroflow Consortium, Children’s Oncology Group, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and French Multicenter Prospective Study),21,22 all designed considering 6- to 8-color FC platforms and using at least 2 analysis tubes. With the availability of newer platforms and fluorochromes, many laboratories have opted for single-tube 8-color2,23,24 or 10-color panels,25,26 achieving optimal performance with decreased labor and reagent costs; faster processing, acquisition, and analysis; and lower specimen requirements. Of note, single-tube 10-color panels have limited capacity to accommodate additional antigens known to be useful in the identification of B-ALL MRD, such as CD73, CD81, CD123, and CD304 (variably used by most but not all consensus panels). In our experience, ∼6% of B-ALLs show only subtle immunophenotypic abnormalities with our panel (supplemental Figure 6), underscoring the potential value of evaluating additional antigens to facilitate MRD assessment. Two recently published single-tube 14-color27 and 15-color28 B-ALL MRD assays show the feasibility of including more useful antigens in a 1-tube setup using newer clinical FC platforms not yet widely available.

On limited dilution studies, our FC panel produced similar results to MRD testing for tumor-specific IG rearrangements down to 0.001% MRD (supplemental Figure 7A). Comparison of our FC MRD results with reverse transcription PCR for BCR:ABL1 in patients with BCR::ABL1 B-ALL showed 90% concordance for any level of positivity (supplemental Figure 7B-C), which is similar to the concordance between consensus FC panels and molecular MRD testing for tumor-specific IG rearrangements (93% concordance using the Euroflow Consortium panel,13 and 96% concordance using the French Multicenter Prospective Study panel29). However, persistence of BCR::ABL1 transcripts on myeloid and nonleukemic lymphoid cells in de novo BCR::ABL1 B-ALL is a well-described phenomenon,30 precluding assessment of test performance based solely on this comparison. In practice, our B-ALL MRD FC results were strongly associated with event-free survival (log-rank hazard ratio, 3.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.277-7.933; P = .0486), and overall survival (log-rank hazard ratio, 2.017; 95% confidence interval, 1.122-3.625; P = .0302; supplemental Figure 8), underscoring the prognostic value of our approach.

The pipeline’s runtime on our current experimental build (Google Vertex AI) was ∼15 to 20 minutes per case. Although analyzer data can be uploaded to our cloud pipeline without any manual preprocessing step, our proposed workflow does preclude immediate analysis after acquisition. Of note, most B-ALL MRD assays by FC are processed and acquired the same day the specimen is received (due to live cell stability concerns), resulting in pipeline exports being available in a timely fashion. Turnaround time (TAT) expectations for B-ALL MRD vary from 1 day to 4 days by FC, and 3 to 9 days by molecular studies, depending on the reference laboratory. Thus, an added processing time of 15 to 20 minutes to B-ALL MRD FC workflows is unlikely to negatively affect overall TAT. Moreover, the computational resources assigned to our pipeline can be easily scaled to increase processing speed and parallel processing of multiple cases at once.

Several limitations of our study need to be considered. Although we have reported similar encouraging results on other FC panels in our practice,31-33 scalability of our pipeline to other laboratories and platforms remains to be demonstrated to assess the clinical impact of our AI-assisted approach on laboratory practice and test accessibility. Our new methodology is designed to decrease manual labor and simplify analysis of FC data but does not by itself improve the diagnostic performance of the test compared with traditional expert analysis. Few unexplained discrepancies between AI-assisted and traditional analysis were encountered at MRD levels of <0.01%, which is not surprising given the gradual loss of concordance at these low MRD levels when comparing 2 different methodologies.13,24,34 Our study cohort included only 3 cases of CD19− B-ALL MRD (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 4B), which was insufficient to study the performance of our AI-enhanced analysis in the setting of B-lineage antigen loss (eg, secondary to anti–B-cell antigen–targeted therapy). However, because our design for AI assistance (anomaly detection and DNN B-lineage classification) is multiparametric and not anchored to a single B-cell antigen, we anticipate our approach to perform well in these settings. Finally, although AI enhancement accelerates the identification of MRD, it does not eliminate the need for expert interpretation of suspected populations on traditional 2-dimensional dot plots.

We hereby introduce CCADDAS, a pipeline designed to process raw files directly from the FC analyzer and produce markedly reduced and software-agnostic data files annotated with powerful AI features. In the setting of B-ALL MRD, CCADDAS has the potential of reducing manual analysis time by at least 83%, without compromising test performance. Our approach is compatible with any clinical FC software, and can be easily adapted to other testing panels or cytometry platforms by retraining with a limited number of negative controls only.31-33 We are actively pursuing the availability of CCADDAS as a cloud computing pipeline available for other laboratories to train, validate, and deploy clinically.

Authorship

Contribution: P.H. and J.N.S. conceptualized the study; P.H., H.O., and M.J.W. were responsible for formal analysis; P.H., H.O., M.J.W., C.C., G.E.O., and M.M.T. performed the investigation; P.H. and J.N.S. developed the methodology; M.S. and H.O. provided resources; J.N.S. developed the software; P.H. and J.N.S. prepared the original draft manuscript; and P.H., A.C., D.J., H.O., and M.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.C. is a consultant for AstraZeneca. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Pedro Horna, Division of Hematopathology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905; email: horna.pedro@mayo.edu.

References

Author notes

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.