Key Points

Obexelimab reduced anti-RBC antibodies production by 25% in unstimulated, by 5%-10% in PHA-, and by 35% in PWM-stimulated cultures.

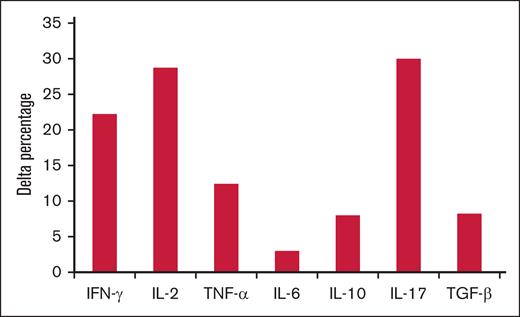

Obexelimab reduced IL-10 in PHA-stimulated cultures and increased interferon gamma, IL-2, IL-17, tumor necrosis factor α, IL-10, and transforming growth factor β in PWM ones.

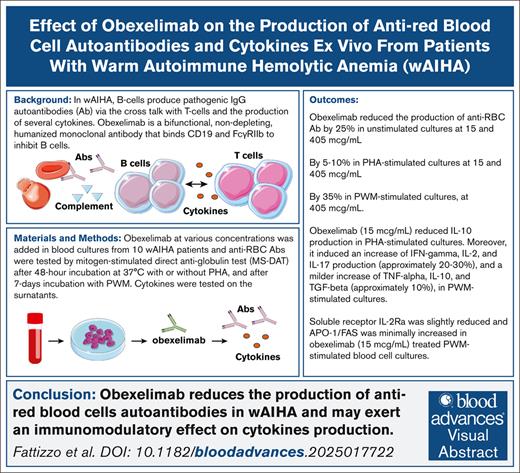

Visual Abstract

Obexelimab is a bifunctional, nondepleting, humanized monoclonal antibody that binds CD19 and FcγRIIb to inhibit the activity of B-lineage cells. It is currently being evaluated in humans with various autoimmune diseases, including warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (wAIHA). In this study, we evaluated the in vitro effect of obexelimab on the production of anti–red blood cell (anti-RBC) autoantibodies and cytokines in blood samples collected from a cohort of patients with wAIHA followed at a single tertiary hematological center. Obexelimab reduced the production of anti-RBC autoantibodies by 25% in unstimulated cultures and by 5% to 10% in phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated cultures, both at 15 and 405 μg/mL. In pokeweed (PWM)-stimulated cultures, obexelimab reached an inhibition of 35% at 405 μg/mL. Obexelimab (15 μg/mL) reduced interleukin-10 (IL-10) production in PHA-stimulated cultures from patients with wAIHA. Moreover, it induced an increase in interferon gamma, IL-2, and IL-17 production (∼20%-30%) and a milder increase in tumor necrosis factor α, IL-10, and transforming growth factor β (∼10%), in PWM-stimulated cultures. Soluble receptor IL-2Ra was slightly reduced and apoptosis antigen 1/FAS was minimally increased in PWM-stimulated blood cell cultures treated with obexelimab (15 μg/mL). Collectively, these findings support the notion that obexelimab exerts an immunomodulatory effect on RBC-specific autoantibody and cytokine production in wAIHA.

Introduction

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is a rare disease with an incidence of 0.8 to 3 per 100 000 people per year and is caused by an autoimmune attack against erythrocyte antigens.1-3 AIHAs are classified as warm (wAIHA) or cold forms (cold agglutinin disease), based on the isotype and thermal amplitude of the pathogenic autoantibody and on the positivity of the direct antiglobulin test (immunoglobulin G [IgG]+ or IgG plus C3d+ in wAIHA vs C3d+ and cold agglutinin detection in cold agglutinin disease).4,5 AIHA displays a multifactorial pathogenesis, including genetic (association with congenital conditions and certain mutations), environmental (drugs, infections (including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), pollution, etc), and miscellaneous factors (solid/hematological neoplasms, systemic autoimmune diseases, etc) contributing to tolerance breakdown. Several mechanisms, such as the level of autoantibody production, of complement activation, monocyte/macrophage phagocytosis, and bone marrow compensation are implicated in the severity of extravascular and intravascular hemolysis.1-3 Management is based on standard therapies that should be differentiated and sequenced according to AIHA type. Patients with wAIHA are initially treated with steroids, followed by rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that depletes CD20-expressing B cells, as second line. The latter is effective in ∼70% to 80% of cases with a median duration of response of 18 months, highlighting the central role that B cells play in disease pathogenesis. Patients failing rituximab represent an unmet clinical need and may be subjected to splenectomy (if young with few comorbidities) or treated with cytotoxic immunosuppressants.4,6,7 Several new drugs targeting complement, phagocytosis, and B cells/plasma cells are in clinical trials for AIHA.3,7-12 Obexelimab is a bifunctional, nondepleting, humanized monoclonal antibody that binds CD19 and FcγRIIb to inhibit the activity of B cells.13 In a small open-label study in IgG4-related disease, treatment with obexelimab led to a rapid and significant reduction in the IgG4 disease index by day 169 in 80% of the patients. Circulating total B cells and plasmablasts were reduced and B-cell activation was inhibited ex vivo.14 Furthermore, the drug was associated with clinical benefits in a subset of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, along with a partial reduction in circulating B cells and a decrease in the expression of genes associated with B-cell and plasma cell activity.15 In wAIHA, it was hypothesized that obexelimab would inhibit CD19+ B cells and plasmablasts, leading to reduced T-/B-cell interaction, release of cytokines, and ultimately autoantibody production. Finally, preliminary data from an ongoing study with obexelimab, administered subcutaneously at a dose of 250 mg daily in patients with primary wAIHA who failed at least 1 prior therapy,16 showed improvement in hemoglobin (Hb) and other biomarkers of anemia.16,17

The objective of this study was to investigate the in vitro effects of obexelimab on the production of anti–red blood cell (RBC) autoantibodies and cytokines in blood samples from a cohort of patients with wAIHA followed at a single tertiary hematological center.

Materials and methods

Patients

Ten patients with active wAIHA were included in the study. Diagnosis was made in the presence of clinical and laboratory hemolytic signs, without any other underlying disease, and a positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT). Active disease was defined by the presence of anemia (Hb <10 mg/dL) and 1 or more of the following markers: lactate dehydrogenase >225 U/L, haptoglobin <10 mg/dL, and adequate reticulocyte counts >121 as per a bone marrow responsiveness index. Patients receiving steroids up to 1 mg/kg per day at the time of sampling were eligible.

The study was conducted within the observational CYTOPAN protocol for the evaluation of diagnosis and management of autoimmune cytopenias (NCT05931718). The protocol OBEBIO was approved by the ethics committees of human experimentation, and patients provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Blood culture conditions

Heparinized blood samples were diluted 1:6 with RPMI 1640 (Gibco-Life Technologies, Foster City, CA) and cultured either unstimulated or stimulated with 2 μg/mL of phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 48 hours and with 1% pokeweed (PWM; Sigma) for 7 days in 24-well plates in the presence of increasing concentrations of obexelimab (5, 15, 45, 135, and 405 μg/mL), anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab (400 μg/mL, comparator), or IgG isotype (5, 45, and 405 μg/mL, neutral). At the end of the culture period, supernatants were harvested and stored at 37°C until assessment for cytokines and measurement of anti-RBC autoantibodies.

Measurement of anti-RBC autoantibodies

The amount of anti–RBC-bound IgG was evaluated by the competitive immune-enzymatic assay mitogen-stimulated DAT, as previously described.18 Briefly, a 96-well polyvinyl chloride assay plate (Costar, Cambridge, MA) was coated with 50 μL of human IgG (Sclavo, Siena, Italy) overnight at +4°C, washed 3 times, and blocked with 200 μL of 2% fetal calf serum–phosphate-buffered saline. The cultured cell suspension was washed 3 times and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated rabbit antihuman IgG (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) at 37°C for 30 minutes. Furthermore, 100 mL of this mixture was added to the IgG-coated plates and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The colorimetric reaction was developed by o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma), and the RBC antibody-bound IgG value was calculated referring to a log/log plot curve. The positivity for mitogen-stimulated DAT was defined as a value exceeding 150 ng/mL, which is the mean of PHA-, phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-, and PWM-stimulated cultures plus 3 standard deviations of 210 healthy blood donors.

Measurement of cytokines

The following cytokine levels were tested on the same culture supernatants of 48-hour unstimulated and PHA-stimulated or 7-day PWM-stimulated cultures tested for anti-RBC antibodies: interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), soluble receptors IL-2Ra (sIL-2Ra) and TNFRI (sTNFRI) (Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN), and apoptosis antigen 1 (APO-1)/FAS (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. Cytokine levels were compared with 10 age- and sex-matched healthy controls.

Statistical analysis

Student t test was used to analyze continuous variables, and χ2 and Wilcoxon tests were used to analyze categorical variables where appropriate.

Results

Clinical and hematological characteristics of patients with AIHA who were studied

Table 1 shows individual clinical and hematological characteristics of the 10 enrolled patients with wAIHA (5 males and 5 females; median age, 56 years; range, 32-68 years). The DAT was positive for IgG in 6 patients, IgG and C3d in 3 patients, and IgG and IgA in 1 patients. Previous therapies included steroids for all patients, rituximab for 4, cyclophosphamide for 1, and azathioprine for 1. At sampling, all patients had an active disease with Hb <10 mg/dL (median, 9.05 mg/dL; range, 6.8-10 mg/dL), increased lactate dehydrogenase, reticulocytes, and unconjugated bilirubin, and reduced haptoglobin. Three patients had started steroids (0.5-1 mg/kg per die) since a maximum of 3 days, 6 were on low-dose steroids (<0.5 mg/kg per die; median dose, 12.5 mg per day of prednisone), and 1 was off therapy. Table 2 shows the individual values of anti-RBC autoantibody levels in vitro in unstimulated, 48-hour PHA-stimulated, and 7-day PWM-stimulated cultures. All patients showed increased values compared to the normal range of healthy controls. As expected, mitogen-stimulation increased anti-RBC autoantibody production.

Clinical and hematological data of the 10 patients with wAIHA

| Patients . | Age, y . | Sex . | DAT-positive . | Prior therapies . | Therapy at sampling∗ . | Hb, g/dL . | Reticulocytes, 109/L . | LDH, UI/L . | ULN . | Unconjugated bilirubin, mg/dL . | Haptoglobin, mg/dL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt1 | 62 | M | IgG | Steroid Rituximab Cyclophosphamide | Steroid | 6.8 | 378 | 1411 | 6.3 | 2.7 | <10 |

| Pt2 | 37 | F | IgG + IgA | Steroid Rituximab | Steroid | 9.9 | 497 | 318 | 1.4 | 1.6 | <10 |

| Pt3 | 68 | M | IgG | Steroid Azathioprine | Steroid | 9.7 | 311 | 446 | 2.0 | 2.4 | <10 |

| Pt4 | 51 | M | IgG + C | Steroid | Steroid | 8.7 | 382 | 286 | 1.3 | 1.3 | <10 |

| Pt5 | 62 | F | IgG + C | Steroid | Steroid | 9.9 | 261 | 221 | 1.0 | 0.9 | <10 |

| Pt6 | 32 | M | IgG | Steroid | No therapy | 10 | 208 | 239 | 1.1 | 0.9 | <10 |

| Pt7 | 68 | M | IgG | Steroid Rituximab | Steroid | 8.2 | 182 | 308 | 1.4 | 2.1 | NA |

| Pt8 | 60 | F | IgG + C | Steroid | Steroid | 9.3 | 162 | 317 | 1.4 | 1.2 | <10 |

| Pt9 | 35 | F | IgG | Steroid Rituximab | Steroid | 8.8 | 122 | 348 | 1.6 | 2.8 | <10 |

| Pt10 | 48 | F | IgG | Steroid | Steroid | 8.5 | 365 | 291 | 1.3 | 2.7 | <10 |

| Patients . | Age, y . | Sex . | DAT-positive . | Prior therapies . | Therapy at sampling∗ . | Hb, g/dL . | Reticulocytes, 109/L . | LDH, UI/L . | ULN . | Unconjugated bilirubin, mg/dL . | Haptoglobin, mg/dL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt1 | 62 | M | IgG | Steroid Rituximab Cyclophosphamide | Steroid | 6.8 | 378 | 1411 | 6.3 | 2.7 | <10 |

| Pt2 | 37 | F | IgG + IgA | Steroid Rituximab | Steroid | 9.9 | 497 | 318 | 1.4 | 1.6 | <10 |

| Pt3 | 68 | M | IgG | Steroid Azathioprine | Steroid | 9.7 | 311 | 446 | 2.0 | 2.4 | <10 |

| Pt4 | 51 | M | IgG + C | Steroid | Steroid | 8.7 | 382 | 286 | 1.3 | 1.3 | <10 |

| Pt5 | 62 | F | IgG + C | Steroid | Steroid | 9.9 | 261 | 221 | 1.0 | 0.9 | <10 |

| Pt6 | 32 | M | IgG | Steroid | No therapy | 10 | 208 | 239 | 1.1 | 0.9 | <10 |

| Pt7 | 68 | M | IgG | Steroid Rituximab | Steroid | 8.2 | 182 | 308 | 1.4 | 2.1 | NA |

| Pt8 | 60 | F | IgG + C | Steroid | Steroid | 9.3 | 162 | 317 | 1.4 | 1.2 | <10 |

| Pt9 | 35 | F | IgG | Steroid Rituximab | Steroid | 8.8 | 122 | 348 | 1.6 | 2.8 | <10 |

| Pt10 | 48 | F | IgG | Steroid | Steroid | 8.5 | 365 | 291 | 1.3 | 2.7 | <10 |

C, DAT positive for complement; F, female; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; M, male; NA, not available; Pt, patient; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Three patients had started steroids (0.5-1 mg/kg per die) since a maximum of 3 days, 6 were on low-dose steroids (<0.5 mg/kg per die), and 1 was without therapy.

Concentrations of anti-RBC autoantibodies detected in unstimulated or mitogen-stimulated cultures in vitro

| Patients . | Unstimulated . | PHA . | PWM . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pt1 | 587 | 816 | 901 |

| Pt2 | 680 | 1010 | 990 |

| Pt3 | 689 | 806 | 851 |

| Pt4 | 850 | 1112 | 1099 |

| Pt5 | 1085 | 1126 | 1265 |

| Pt6 | 2725 | 2689 | 2889 |

| Pt7 | 402 | 446 | 503 |

| Pt8 | 736 | 982 | 911 |

| Pt9 | 702 | 987 | 1230 |

| Pt10 | 1024 | 1316 | 1453 |

| Mean | 948 | 1129 | 1209 |

| SE | 207 | 288 | 204 |

| Patients . | Unstimulated . | PHA . | PWM . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pt1 | 587 | 816 | 901 |

| Pt2 | 680 | 1010 | 990 |

| Pt3 | 689 | 806 | 851 |

| Pt4 | 850 | 1112 | 1099 |

| Pt5 | 1085 | 1126 | 1265 |

| Pt6 | 2725 | 2689 | 2889 |

| Pt7 | 402 | 446 | 503 |

| Pt8 | 736 | 982 | 911 |

| Pt9 | 702 | 987 | 1230 |

| Pt10 | 1024 | 1316 | 1453 |

| Mean | 948 | 1129 | 1209 |

| SE | 207 | 288 | 204 |

Values are expressed as nanograms per milliliter of RBC-bound IgG. Normal range: negative, <150 IgG ng/mL; weak positive, 150 to 250 IgG ng/mL; and positive, >250 IgG ng/mL.

SE, standard error.

Effect of obexelimab on the production of anti-RBC autoantibodies in vitro in patients with wAIHA

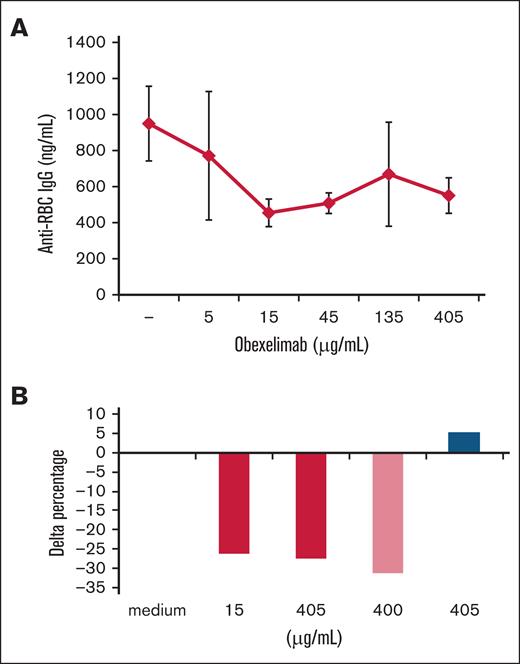

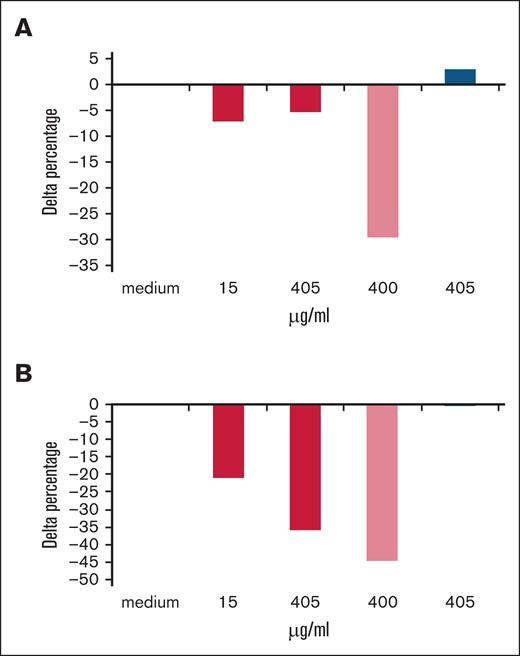

In 48-hour unstimulated cultures (Figure 1A-B), obexelimab reduced the production of anti-RBC autoantibodies in a dose-dependent fashion with maximal effect at 15 μg/mL or higher doses. Anti-RBC levels were significantly reduced by 25% with 15 and 405 μg/mL of obexelimab, similarly to the reduction observed with rituximab. In 48-hour PHA-stimulated cultures (Figure 2A), the production of anti-RBC autoantibodies was reduced by 5% to 10%. In 7-day PWM-stimulated cultures (Figure 2B), obexelimab reduced the production of anti-RBC autoantibodies to a greater extent and in a dose-dependent fashion, reaching a 35% reduction at 405 μg/mL (P < .05). Control cultures with rituximab also showed a reduction in anti-RBC autoantibody production, whereas the control isotype had no effect, as expected.

Effect of obexelimab on the in vitro production of anti-RBC autoantibodies in 48-hour unstimulated cultures. (A) Mean ± standard error (SE) of anti-RBC IgG production (nanograms per milliliter) in the presence of different concentrations of obexelimab. (B) Delta percentage of anti-RBC autoantibody production with obexelimab (red), rituximab (light red), and control IgG isotype (blue) compared with that with medium alone. Delta percentage was calculated for each cytokine in the presence of obexelimab (15 μg/mL) over cultures performed in the absence of the drug.

Effect of obexelimab on the in vitro production of anti-RBC autoantibodies in 48-hour unstimulated cultures. (A) Mean ± standard error (SE) of anti-RBC IgG production (nanograms per milliliter) in the presence of different concentrations of obexelimab. (B) Delta percentage of anti-RBC autoantibody production with obexelimab (red), rituximab (light red), and control IgG isotype (blue) compared with that with medium alone. Delta percentage was calculated for each cytokine in the presence of obexelimab (15 μg/mL) over cultures performed in the absence of the drug.

Effect of obexelimab on the in vitro production of anti-RBC autoantibodies in stimulated cultures. Delta percentage of anti-RBC autoantibodies production with obexelimab (red), rituximab (light red), and control IgG isotype (blue) in 48-hour PHA-stimulated (A) and 7-day PWM-stimulated cultures (B). Delta percentage was calculated for each cytokine in the presence of obexelimab (15 μg/mL) over cultures performed in the absence of the drug.

Effect of obexelimab on the in vitro production of anti-RBC autoantibodies in stimulated cultures. Delta percentage of anti-RBC autoantibodies production with obexelimab (red), rituximab (light red), and control IgG isotype (blue) in 48-hour PHA-stimulated (A) and 7-day PWM-stimulated cultures (B). Delta percentage was calculated for each cytokine in the presence of obexelimab (15 μg/mL) over cultures performed in the absence of the drug.

Effect of obexelimab on the production of cytokines and soluble receptors in vitro in patients with wAIHA

Table 3 shows the level of T helper 1 (Th1)-associated (IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α), Th2-associated (IL-6), and immunomodulatory cytokines (IL-10, IL-17, and TGF-β), along with sTNFRI, sIL-2Ra, and soluble APO-1/FAS, in 48-hour unstimulated, PHA-stimulated, and 7-day PWM-stimulated blood cultures from patients with AIHA and healthy controls. Overall, unstimulated cultures showed negligible cytokine production, whereas PHA stimulation resulted in up to 30-fold increases in all cytokines, with the exception of TGF-β that displayed comparable production in unstimulated and mitogen-stimulated cultures. Comparing unstimulated cultures from patients with wAIHA and controls, we observed that IL-10, sTNFRI, sIL-2Ra, and APO-1/FAS were significantly increased in the former, while the other factors were comparable. Similarly, in PHA-stimulated cultures, sTNFRI, APO-1/FAS, IL-2, and IL-10 levels were higher (significantly for sTNFR1 and APO-1/FAS only) and IL-6 was lower in patients vs controls. Finally, in PWM-stimulated cultures, IFN-γ and IL-6 production was significantly lower in patients with wAIHA vs controls. IL-17 production was higher in patients vs controls, although not significantly. These data show an overall different cytokine modulation in patients vs controls in both PHA- and PWM-stimulated cultures.

Cytokine production in unstimulated and mitogen-stimulated cultures from 10 patients with wAIHA and controls

| Cytokine . | Unstimulated . | PHA . | PWM . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients . | Controls . | Patients . | Controls . | Patients . | Controls . | |

| IFN-γ | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 197 ± 175 | 242 ± 82 | 519 ± 161∗ | 707 ± 9.5 |

| IL-2 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 136 ± 134 | 2.0 ± 1.6 | 6.9 ± 6.2 | 23.2 ± 10.6 |

| TNF-α | 9 ± 0.7 | 10 ± 0.5 | 348 ± 306 | 308 ± 68 | 36 ± 0.6 | 202 ± 75 |

| IL-6 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 34 ± 16 | 182 ± 87† | 721 ± 6.4 | 420 ± 13† | 752 ± 2.8 |

| IL-10 | 13.9 ± 4.2† | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 308 ± 246 | 16.8 ± 7.2 | 15.1 ± 11.5 | 26.9 ± 5.1 |

| IL-17 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 138 ± 101 | 47 ± 9.7 | 616 ± 593 | 360 ± 119 |

| TGF-β | 1523 ± 176 | 1574 ± 253 | 1815 ± 202 | 1919 ± 191 | 1363 ± 15 | 1765 ± 164 |

| sTNFRI | 391 ± 70† | 156 ± 9 | 519 ± 78† | 210 ± 14 | 419 ± 182 | 263 ± 15 |

| sIL-2Ra | 186 ± 30† | 62.6 ± 6.8 | 523 ± 316 | 321 ± 70 | 2190 ± 1826 | 3324 ± 579 |

| APO-1/FAS | 276 ± 36∗ | 162 ± 13 | 291 ± 11† | 176 ± 15 | 266 ± 34 | 233 ± 19 |

| Cytokine . | Unstimulated . | PHA . | PWM . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients . | Controls . | Patients . | Controls . | Patients . | Controls . | |

| IFN-γ | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 197 ± 175 | 242 ± 82 | 519 ± 161∗ | 707 ± 9.5 |

| IL-2 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 136 ± 134 | 2.0 ± 1.6 | 6.9 ± 6.2 | 23.2 ± 10.6 |

| TNF-α | 9 ± 0.7 | 10 ± 0.5 | 348 ± 306 | 308 ± 68 | 36 ± 0.6 | 202 ± 75 |

| IL-6 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 34 ± 16 | 182 ± 87† | 721 ± 6.4 | 420 ± 13† | 752 ± 2.8 |

| IL-10 | 13.9 ± 4.2† | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 308 ± 246 | 16.8 ± 7.2 | 15.1 ± 11.5 | 26.9 ± 5.1 |

| IL-17 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 138 ± 101 | 47 ± 9.7 | 616 ± 593 | 360 ± 119 |

| TGF-β | 1523 ± 176 | 1574 ± 253 | 1815 ± 202 | 1919 ± 191 | 1363 ± 15 | 1765 ± 164 |

| sTNFRI | 391 ± 70† | 156 ± 9 | 519 ± 78† | 210 ± 14 | 419 ± 182 | 263 ± 15 |

| sIL-2Ra | 186 ± 30† | 62.6 ± 6.8 | 523 ± 316 | 321 ± 70 | 2190 ± 1826 | 3324 ± 579 |

| APO-1/FAS | 276 ± 36∗ | 162 ± 13 | 291 ± 11† | 176 ± 15 | 266 ± 34 | 233 ± 19 |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard error in picograms per milliliter.

P < .05 vs controls.

P < .001 vs controls.

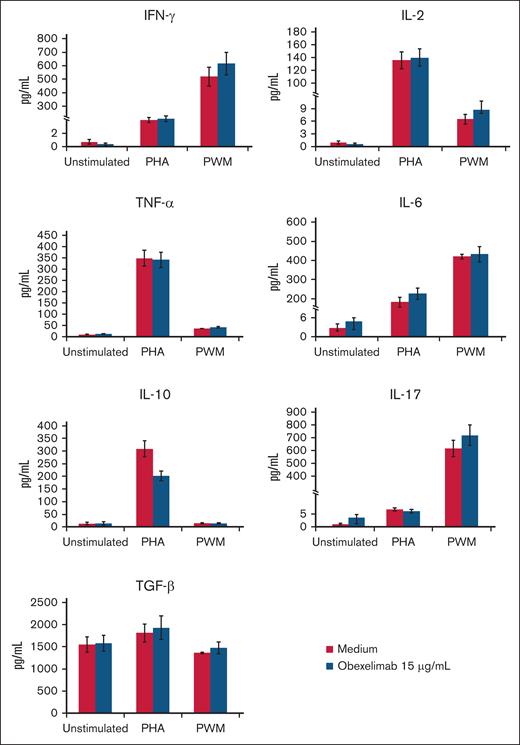

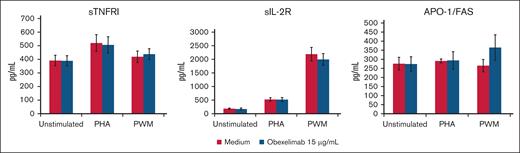

Figures 3-5 illustrate the effect of obexelimab (15 μg/mL) on cytokine production in the blood cultures. Overall, obexelimab did not significantly affect the production of cytokines, although there was a trend for reduced IL-10 production in PHA-stimulated cultures compared with that in untreated ones. Similarly, obexelimab had minimal effect on the production of the soluble receptors with the exception of a slight, but not significant, increase in APO-1/FAS in PWM-stimulated cultures (Figure 4).

Effect of obexelimab on cytokine production in vitro. Values are expressed as mean ± SE; 48-hour PHA-stimulated and 7-day PWM-stimulated cultures.

Effect of obexelimab on cytokine production in vitro. Values are expressed as mean ± SE; 48-hour PHA-stimulated and 7-day PWM-stimulated cultures.

Effect of obexelimab on in vitro cytokine production in PWM-stimulated cultures expressed as delta percentage. Delta percentage was calculated for each cytokine in the presence of obexelimab (15 μg/mL) over cultures performed in the absence of the drug.

Effect of obexelimab on in vitro cytokine production in PWM-stimulated cultures expressed as delta percentage. Delta percentage was calculated for each cytokine in the presence of obexelimab (15 μg/mL) over cultures performed in the absence of the drug.

Effect of obexelimab on the in vitro production of soluble TNF and IL-2 receptors and Apo/Fas. Values are expressed as mean ± SE; 48-hour PHA-stimulated and 7-day PWM-stimulated cultures.

Effect of obexelimab on the in vitro production of soluble TNF and IL-2 receptors and Apo/Fas. Values are expressed as mean ± SE; 48-hour PHA-stimulated and 7-day PWM-stimulated cultures.

Discussion

Here, we investigated, to our knowledge, for the first time the in vitro effect of obexelimab on the production of anti-RBC autoantibodies and cytokines in patients with active wAIHA, including some with refractory disease. We used a well-documented and highly sensitive method of mitogen-stimulation to amplify autoantibody production, as shown in several diseases including AIHA, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and myelofibrosis.18-22 Obexelimab effect varied according to the experimental condition. In particular, we found that the drug significantly reduced the production of anti-RBC autoantibody by 25% at 15 and 405 μg/mL concentrations in 48-hour unstimulated cultures (where the difference among patients and healthy controls was maximal). Obexelimab was less effective in reducing anti-RBC autoantibody production in PHA-stimulated cultures. This finding is not surprising given that PHA selectively activates T cells rather than B cells. In contrast, in 7-day cultures stimulated with PWM, which is more selective for B cells, obexelimab reduced anti-RBC autoantibodies by 35%. Importantly, the control IgG isotype showed negligible effects, whereas the control anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab confirmed its inhibitory activity. These results are consistent with previous preliminary reports showing a clinical benefit of obexelimab in wAIHA,17 IgG4-related disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus14,15 and with a preclinical study of an obexelimab surrogate monoclonal antibody in a humanized mouse model of lupus.23

In the case of cytokine levels, IL-2 and IL-17 were higher in patients with wAIHA than in healthy controls, likely due to their role in promoting T-cell responses and inflammation. IL-10 was significantly increased in unstimulated and PHA-stimulated samples but not in PWM stimulated ones, suggesting that IL-10 production increases upon T-cell stimulation. IL-10 is produced by monocytes, T regulatory cells, and Th2 cells; furthermore, IL-10 promotes Th2 vs Th1 polarization that has been linked to antibody-mediated production in wAIHA. Conversely, IL-6, previously reported as increased in AIHA,24,25 was lower in unstimulated and mitogen-stimulated cultures from patients vs controls, possibly because of the immunoregulatory activity of IL-10. Similarly, IFN-γ levels were lower in PHA and PWM stimulated cultures from patients with wAIHA vs controls, as already reported.24,25 Lower IFN-γ may further promote Th2 responses in patients with wAIHA. Notably, this analysis is not fully comparable with data reported for cytokine levels in the serum from patients with AIHA3,24-29 because of the different experimental conditions and the evaluation of a single cross-sectional time point in the study. Finally, sTNFRI, sIL-2Ra, and APO-1/FAS were increased in patients vs controls in most experimental conditions, particularly in unstimulated and PHA-stimulated cultures. In general, soluble receptors are hypothesized to exert inhibitory activity on the corresponding cytokines, namely TNF-α and IL-2, by acting as a decoy receptor and cytokine sink, which are known inflammatory and Th1 mediators, respectively. The increased APO-a/FAS levels may be attributed to an increased rate of programmed cell death in patients with wAIHA because of the ongoing inflammatory and autoimmune process in these individuals.

The addition of obexelimab had minimal effect on cytokine or soluble receptor production, regardless of the experimental conditions. Interestingly, obexelimab reduced IL-10 production in PHA-stimulated cultures (where T cells were maximally stimulated). The inhibition of this Th2-promoting cytokine might be beneficial in wAIHA. Accordingly, obexelimab has been shown to reduce the production of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-10 by purified human B cells from healthy volunteers in vitro.13 The cytokine results described here also differ from those reported by Szili et al, likely reflecting the differences in the cell stimuli and culture conditions that were used.

This study carries several limitations, including a small sample size, single center cohort, as well as concurrent steroid use that might have had an impact on cytokine studies. However, this is the first systematic evaluation of obexelimab effect on the production of anti-RBC antibodies in cultures from wAIHA samples and may provide hints for an immunomodulatory effect of the drug.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that obexelimab decreases the production of anti-RBC autoantibodies in vitro, although with a limited effect on cytokine levels, suggesting a potential immunomodulatory role in patients with wAIHA.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Zenas Pharmaceuticals as an investigator-sponsored study, as per the OBEBIO protocol.

This research was funded by Italian Ministry of Health; current research, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Policlinico Milano.

Authorship

Contribution: B.F. and W.B. designed the study, followed the patients, analyzed the data, and wrote and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; A.Z. designed the study, performed the laboratory tests, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; and G.L.P., F.P., and M.B. revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Bruno Fattizzo, SC Ematologia, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, via F Sforza 35, 20100 Milan, Italy; email: bruno.fattizzo@unimi.it.

References

Author notes

B.F. and A.Z. contributed equally to this study.

All data have been included in the manuscript. Further information is available from the corresponding author, Bruno Fattizzo (bruno.fatizzo@unimi.it), on reasonable request.