Key Points

Narsoplimab-treated patients with TA-TMA had significant reductions in mortality risk in analyses using well-matched external controls.

Based on robust comparative analyses, narsoplimab is a potential option to provide significant survival benefits to patients with TA-TMA.

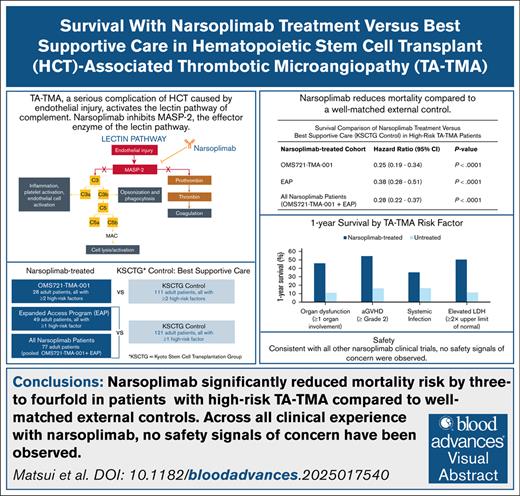

Visual Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant–associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) is a potentially fatal multisystem complication of hematopoietic cell transplantation for which there is no approved treatment. In a single-arm study (NCT02222545), narsoplimab treatment for TA-TMA demonstrated a median overall survival (OS) of 274 days from date of diagnosis. Here, we compare OS observed in 2 cohorts treated with narsoplimab to OS in a well-matched external control to test survival benefit in patients with high-risk TA-TMA. OS in patients (aged ≥16 years) with high-risk TA-TMA treated with narsoplimab in a single-arm, open-label study (NCT02222545) or in the narsoplimab expanded access program (EAP; NCT04247906) was compared with OS in a control group with high-risk TA-TMA from the Kyoto Stem Cell Transplantation Group (KSCTG) registry. Narsoplimab-treated patients in the single-arm study (N = 28) had a fourfold reduction in risk of mortality compared with patients from the KSCTG registry (N = 111; hazard ratio [HR], 0.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.19, 0.34; P < .0001). Similarly, in high-risk patients treated with narsoplimab in the EAP (N = 49), mortality risk was significantly lower than among high-risk patients from the KSCTG registry (N = 121; HR 0.38; 95% CI 0.28, 0.51; P < .0001). When narsoplimab-treated patients from the single-arm study and the EAP (N = 77) were compared with KSCTG patients, the HR for mortality was 0.28 (95% CI, 0.22, 0.37; P < .0001). In conclusion, in patients with high-risk TA-TMA, narsoplimab treatment significantly reduced mortality relative to a well-matched external control group who did not receive narsoplimab. These results support narsoplimab as a potential therapeutic option for TA-TMA.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant–associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) is a serious and life-threatening complication of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).1 Endothelial injury occurring before, during, and after HCT, together with fibrin aggregates and platelet-rich thrombi in the microvasculature, can lead to end-organ damage and patient death,2-5 with mortality in severe cases exceeding 90%.1

To date, there are no approved products for the treatment of TA-TMA. Complement C5 inhibitors, eculizumab and ravulizumab, are used off-label to treat TA-TMA, with variable outcomes.6-10 Defibrotide, which is indicated for veno-occlusive disease, another complication arising from endothelial injury, is also used off-label with limited success.11,12 Despite its high rates of morbidity and mortality, TA-TMA still lacks reliable interventions, and there remains a substantial unmet medical need for an effective therapy.

Complement activation by endothelial injury associated with HCT is implicated in the development and pathophysiology of TA-TMA.4,13-15 The lectin pathway of complement is directly initiated by the damage-associated molecular patterns exposed on the surface of injured cells, including damaged endothelial cells in TA-TMA.15,16 Mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease 2 (MASP-2) is the effector enzyme of the lectin pathway of complement. In addition to its role in activating the lectin pathway of complement, MASP-2 also activates the coagulation cascade by converting prothrombin to thrombin and cleaving factors XII and XIIa.17-19

Narsoplimab, a monoclonal antibody currently under regulatory review for the treatment of TA-TMA, binds to and blocks MASP-2, inhibiting the inflammatory and prothrombotic responses to endothelial injury.20 There is strong mechanistic evidence demonstrating that suppression of lectin pathway activity via MASP-2 inhibition modulates key pathologic processes that characterize TA-TMA, including complement activation, endothelial injury, and microvascular thrombosis.15,18,21,22

Plasma of patients with TMA contains elevated MASP-2 levels and induces microvascular endothelial cell apoptosis, which can be substantially inhibited by narsoplimab.20 Likewise, plasma of patients with TA-TMA, but not that of allogeneic HCT recipients without TMA, induces apoptosis in microvascular endothelial cell, which is similarly blocked by narsoplimab.21 Furthermore, plasma from patients with TA-TMA who responded to narsoplimab treatment induced substantially less apoptotic injury in microvascular endothelial cells compared with plasma collected from the same patients before initiation of narsoplimab treatment.21 In a different experimental system, serum from patients with TA-TMA also induced C5b-9 deposition and thrombus formation on microvascular endothelial cells; both effects were substantially inhibited by narsoplimab.22

Taken together, these data demonstrate that, by blocking MASP-2, narsoplimab inhibits TA-TMA–related complement activation, endothelial injury/apoptosis, and thrombosis, all of which are directly related to the clinical syndrome of TA-TMA and collectively lead to end-organ damage.

In a previously published single-arm pivotal trial of 28 patients with high-risk TA-TMA, IV narsoplimab administered once weekly for 4 to 8 weeks demonstrated a response rate of 61%. To be considered a responder, a patient was required to have improvement in laboratory values (platelet count and lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] levels) and in clinical outcome (organ function and/or transfusion independence). Organ function improvement was observed in 74% of patients, and median overall survival (OS) was 274 days from date of TMA diagnosis. This response was consistent across all patient subgroups, with no safety signals of concern.23 Additionally, there is a growing body of evidence from the narsoplimab expanded access program (EAP) demonstrating that narsoplimab treatment results in improved outcomes for adult and pediatric patients in a real-world setting.24-32 These findings, however, have not yet been validated by a formal statistical comparison with a control group. Here, we build on the results of the single-arm trial and on the observations from the EAP to provide statistical comparisons of narsoplimab-treated patients with a well-matched external control group to test the hypothesis that narsoplimab provides a significant survival benefit for patients with TA-TMA.

Methods

Patient population

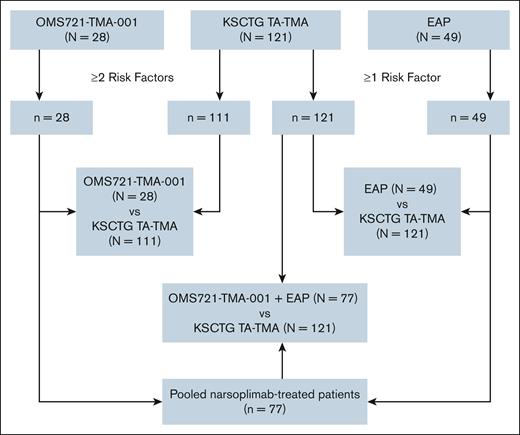

Three sets of comparative analyses of patients (aged ≥16 years) with high-risk TA-TMA were conducted, with data for the analyses obtained from 3 sources (Figure 1). There were 2 narsoplimab-treated cohorts: 1 cohort of patients enrolled in the pivotal clinical trial OMS721-TMA-001 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02222545) and the other from an EAP (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04247906). The narsoplimab EAP provided access to narsoplimab for patients with TA-TMA who, in the opinion of their physician, had no other suitable treatment option and no access to a clinical trial.

Flow diagram for comparative analyses cohorts. Flow diagram depicting the 3 different cohorts included in the comparative analyses. Of 121 patients with TA-TMA from the KSCTG registry, 111 had ≥2 risk factors for death/poor outcome and, therefore, were the comparison group vs patients from the OMS721-TMA-001 study. All 121 KSCTG patients with TA-TMA had ≥1 high-risk factor and were compared with patients in the EAP cohort.

Flow diagram for comparative analyses cohorts. Flow diagram depicting the 3 different cohorts included in the comparative analyses. Of 121 patients with TA-TMA from the KSCTG registry, 111 had ≥2 risk factors for death/poor outcome and, therefore, were the comparison group vs patients from the OMS721-TMA-001 study. All 121 KSCTG patients with TA-TMA had ≥1 high-risk factor and were compared with patients in the EAP cohort.

Patients were enrolled in the OMS721-TMA-001 trial between August 2015 and October 2019 and were administered IV narsoplimab once weekly for 4 to 8 weeks.23 An exclusion criterion of the study included receipt of eculizumab within 3 months of screening for the study. In the EAP, patients were enrolled from 2019 to 2023 and received IV narsoplimab twice weekly; the frequency could be increased to 3 times per week if the physician deemed it necessary. Only EAP patients who received narsoplimab as first-line treatment were included in the analyses reported herein.

The control group included patients from the Kyoto Stem Cell Transplantation Group (KSCTG) registry who were diagnosed with TA-TMA. The KSCTG registry includes data for HCT recipients from 17 institutions across Japan (Kyoto University and its affiliated hospitals). The registry enrolled patients (aged ≥16 years) with hematologic diseases who received an allogeneic HCT between 1 January 2000 and 30 September 2016. Patients identified by treating physicians as having TA-TMA had the diagnosis confirmed by a separate review, following standardized criteria, of medical records and extraction of data related to diagnosis, management, and outcomes of TA-TMA.33,34

The inclusion criteria for the OMS721-TMA-001 study and the KSCTG TA-TMA study have been published23,34 and are summarized here. For the OMS721-TMA-001 study, patients were required to have a platelet count of <150 000/μL, evidence of microangiopathic hemolysis, renal dysfunction, and anemia or thrombocytopenia without an alternative explanation. For the KSCTG TA-TMA study, patients needed to fulfill at least 2 of the 5 following criteria: presence of erythrocyte fragmentation and schistocytes, increased serum LDH levels above institutional baseline, de novo prolonged or progressive thrombocytopenia or anemia, concurrent renal dysfunction and/or neurological dysfunction without other causes, and negative direct and indirect Coombs test results or a decrease in serum haptoglobin concentration. Patients could enroll in the EAP if they had thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and, as stated in the Patient population section, had no access to other treatment. All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by institutional or central review boards, and written informed consent was obtained within each study.23,34

Definition of high-risk TA-TMA

To ensure that comparable patient populations were included in each of the 3 cohorts, all patients were required to meet criteria for high-risk TA-TMA as described by Schoettler et al.35 Prognostic risk factors for poor outcomes/death in these 3 groups included any 1 of the following: elevated LDH of ≥2× the upper limit of normal (ULN), acute graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) of grade 2 to 4, organ dysfunction (renal, pulmonary, and/or neurological), and infection.

Patients were excluded if they had missing data on survival or if they had received complement-inhibitor or defibrotide treatment before receipt of narsoplimab for their TA-TMA.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analysis plan was independently prespecified, designed, and approved by all authors. The prespecified statistical analyses were conducted by Omeros Corporation and all authors had access to the primary data. Outputs of all analyses were independently reviewed and objectively interpreted by the authors. Three sets of analyses were conducted to test our hypothesis: a comparison of survival for patients treated with narsoplimab in study OMS721-TMA-001 with that of the KSCTG control patients with TA-TMA; a comparison of survival for patients aged ≥16 years in the EAP who did not receive previous treatment for TA-TMA with that of the KSCTG TA-TMA cohort; and finally, a comparison of survival for all narsoplimab-treated patients combined (ie, from study OMS721-TMA-001 and from the EAP) with that of the KSCTG control patients with TA-TMA.

The end point of OS was defined as time to death or, for those patients without death recorded, time to date of last known “alive” status, and was measured in days, starting from date of TA-TMA diagnosis. OS was analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards model with the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) approach to compare the 2 treatment arms (narsoplimab-treated patients and KSCTG control patients). IPTW adjusts for confounding in observational studies in which patients are assigned different weights based on their propensity to receive treatment. This approach aims to create a pseudopopulation in which the distributions of covariates are similar between treatment groups. Propensity scores were estimated using a logistic regression model. The model included as covariates age, sex, and the following 6 risk factors: elevated LDH of ≥2× ULN, acute GVHD of grade 2 to 4, renal dysfunction, pulmonary dysfunction, neurological dysfunction, and infection. This propensity score approach allowed the primary analysis model to account for differences in characteristics among narsoplimab-treated patients and in the KSCTG patients with TA-TMA. For each analysis, the propensity model was fit for the likelihood of being in the narsoplimab-treated cohort. The propensity score was calculated for each patient in the narsoplimab-treated cohort and in the KSCTG TA-TMA group, and the primary analysis model was run with each patient’s propensity score as an inverse weight. The primary analysis used a comparative survival analysis model that included all covariates used in the propensity scores estimation (age, sex, and the 6 aforementioned risk factors).

Multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the primary analysis and included (1) OS with only treatment and no weighting, (2) OS with only treatment and the IPTW, (3) OS with propensity score stratification, and (4) OS with 1:1 and 1:2 propensity score–matched patients, with and without the specified risk factors.

Results

Patient population

For the OMS721-TMA-001 study cohort, 28 patients (aged ≥18 years) who underwent allogeneic HCT and were diagnosed with TA-TMA were included (Figure 1). All 28 patients had ≥2 risk factors for poor outcomes/death as established by the International Harmonization Criteria.35

In the EAP, 136 patients with TA-TMA received at least 1 dose of narsoplimab as of October 2023. Of 84 patients aged ≥16 years who underwent allogeneic HCT, 65 were confirmed to have ≥1 high-risk factors for poor outcomes/death. Forty-nine of these patients reported no previous treatment for TA-TMA (ie, no eculizumab, ravulizumab, pegcetacoplan, and/or defibrotide). All 49 patients were included in the comparative survival analysis. No patient was excluded from the analysis due to missing data or for any other reason.

A total of 121 patients with TA-TMA (aged ≥16 years) from the KSCTG registry were included in the analyses. Of these, 111 had ≥2 risk factors for poor outcome/death and, therefore, were the comparison group vs OMS721-TMA-001 patients (Figure 1). All 121 KSCTG patients with TA-TMA had at least 1 high-risk factor and formed the basis for comparison with the EAP cohort and the pooled narsoplimab-treated group.

Demographics for each group of patients included in the analyses are presented in Table 1. Age and sex were similar across groups, with median ages of 48, 55, and 52 years for the OMS721-TMA-001, EAP, and KSCTG TA-TMA cohorts, respectively, and men comprising most patients across all 3 cohorts (51.0%-71.4%). More patients in the KSCTG group had unrelated stem cell donors (72.7%) compared with OMS721-TMA-001 (57.1%). Bone marrow as the cell source was used in 43.8% of KSCTG patients, followed by unrelated cord blood (38.8%). In contrast, unrelated cord blood was the source for 7.1% of patients in study OMS721-TMA-001, with 71.4% of patients receiving peripheral blood stem cells. Information on donors and cell source was unknown in one-third of the patients in the EAP, making comparisons difficult. Approximately half of the OMS721-TMA-001 (53.5%) and KSCTG (48.8%) patients underwent a reduced intensity conditioning regimen, with slightly less reported for the EAP (40.8%); the conditioning regimen was unknown in 18% of EAP patients. Duration from HCT to TA-TMA diagnosis was shortest in the KSCTG TA-TMA cohort (35 days) and longest in study OMS721-TMA-001 (119 days). The median number of doses in the 2 narsoplimab-treated cohorts was similar, 8 in the clinical trial and 10 in the EAP, with median duration of treatment slightly shorter in the EAP group compared with that of the OMS721-TMA-001 study (6 vs 8 weeks, respectively).

Patient demographics by group

| . | KSCTG TA-TMA N = 121 . | OMS721-TMA-001 N = 28 . | EAP N = 49 . | OMS721-TMA-001 + EAP N = 77 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 52 (40-61) | 48 (36.5-58.0) | 55.4 (29.8-63.4) | 49 (33-62) |

| Min, max | 17, 74 | 22, 68 | 16, 71.7 | 16, 71.7 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 73 (60.3) | 20 (71.4) | 25 (51.0) | 45 (58.4) |

| Female | 48 (39.7) | 8 (28.6) | 24 (49.0) | 32 (41.6) |

| Time from HCT to TMA diagnosis, d | ||||

| n | 121 | 28 | 45 | 73 |

| Median | 35 | 119 | 94.5 | 85 |

| Min, max | 3, 410 | 33, 444 | 0, 1042 | 0, 1042 |

| Related donor, n (%) | ||||

| Related | 33 (27.3) | 12 (42.9) | 17 (34.7) | 29 (37.7) |

| Unrelated | 88 (72.7) | 16 (57.1) | 18 (36.7) | 34 (44.2) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 16 (32.7) | 16 (20.8) |

| Cell source, n (%) | ||||

| BM | 53 (43.8) | 6 (21.4) | 5 (10.2) | 11 (14.3) |

| PBSC | 21 (17.4) | 20 (71.4) | 28 (57.1) | 48 (62.3) |

| Unrelated CB | 47 (38.8) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (4.1) | 4 (5.2) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 16 (32.7) | 16 (20.8) |

| HCT conditioning regimen, n (%) | ||||

| Reduced intensity conditioning | 59 (48.8) | 15 (53.5) | 20 (40.8) | 36 (46.8) |

| Myeloablative conditioning | 62 (51.2) | 13 (46.4) | 15 (30.6) | 27 (35.1) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 9 (18.4) | 9 (11.7) |

| Narsoplimab treatment,∗median (min, max) | ||||

| No. of doses | NA | 8 (2, 8) | 10 (1, 54) | ND |

| Duration of treatment, wk | NA | 8 (2, 16.4) | 6 (0.1, 31.7) | ND |

| . | KSCTG TA-TMA N = 121 . | OMS721-TMA-001 N = 28 . | EAP N = 49 . | OMS721-TMA-001 + EAP N = 77 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 52 (40-61) | 48 (36.5-58.0) | 55.4 (29.8-63.4) | 49 (33-62) |

| Min, max | 17, 74 | 22, 68 | 16, 71.7 | 16, 71.7 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 73 (60.3) | 20 (71.4) | 25 (51.0) | 45 (58.4) |

| Female | 48 (39.7) | 8 (28.6) | 24 (49.0) | 32 (41.6) |

| Time from HCT to TMA diagnosis, d | ||||

| n | 121 | 28 | 45 | 73 |

| Median | 35 | 119 | 94.5 | 85 |

| Min, max | 3, 410 | 33, 444 | 0, 1042 | 0, 1042 |

| Related donor, n (%) | ||||

| Related | 33 (27.3) | 12 (42.9) | 17 (34.7) | 29 (37.7) |

| Unrelated | 88 (72.7) | 16 (57.1) | 18 (36.7) | 34 (44.2) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 16 (32.7) | 16 (20.8) |

| Cell source, n (%) | ||||

| BM | 53 (43.8) | 6 (21.4) | 5 (10.2) | 11 (14.3) |

| PBSC | 21 (17.4) | 20 (71.4) | 28 (57.1) | 48 (62.3) |

| Unrelated CB | 47 (38.8) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (4.1) | 4 (5.2) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 16 (32.7) | 16 (20.8) |

| HCT conditioning regimen, n (%) | ||||

| Reduced intensity conditioning | 59 (48.8) | 15 (53.5) | 20 (40.8) | 36 (46.8) |

| Myeloablative conditioning | 62 (51.2) | 13 (46.4) | 15 (30.6) | 27 (35.1) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 9 (18.4) | 9 (11.7) |

| Narsoplimab treatment,∗median (min, max) | ||||

| No. of doses | NA | 8 (2, 8) | 10 (1, 54) | ND |

| Duration of treatment, wk | NA | 8 (2, 16.4) | 6 (0.1, 31.7) | ND |

BM, bone marrow; CB, cord blood; IQR, interquartile range; max, maximum; min, minimum; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells.

Narsoplimab treatment is reported separately for OMS721-TMA-001 and the EAP. This was not calculated for the pooled population.

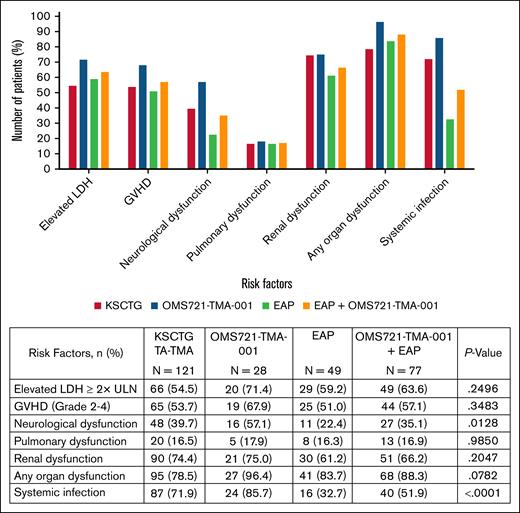

The distribution of high-risk factors in each group is depicted in Figure 2. All groups had similar proportions of patients with each specified risk factor, except for systemic infections, which were reported at a lower frequency in patients from the EAP. Specifically, organ dysfunction was present in 96.4% of OMS721-TMA-001 patients, 83.7% in the EAP, and 78.5% in the KSCTG control group. Across all groups, renal dysfunction was most commonly reported at 75.0% in study OMS721-TMA-001, 61.2% in the EAP, and 74.4% in the KSCTG TA-TMA cohort.

Survival analyses

The estimated 1-year OS was 41.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 21.6-60.4) and 58.0% (95% CI, 43.2-72.7) in OMS721-TMA-001 and EAP patients treated with narsoplimab, respectively, vs 16.9% (95% CI, 10.2-23.7) in the KSCTG TA-TMA control group patients. The corresponding median survival was estimated at 274+ days for narsoplimab-treated patients compared with 41 days for the KSCTG TA-TMA control cohort.

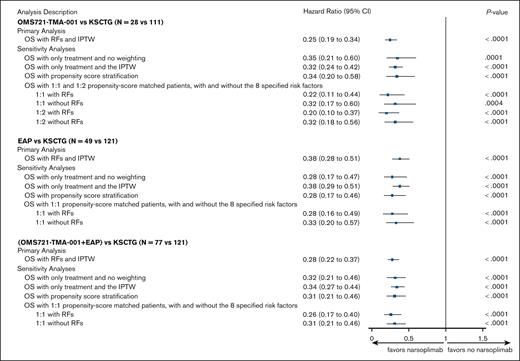

The estimated hazard ratios (HR) for the primary OS Cox proportional hazards model for the 3 analysis groups and corresponding sensitivity analyses are presented in Figure 3. Patients treated with narsoplimab had a statistically significant reduction in mortality compared with the KSCTG TA-TMA control group, with an HR of 0.25 for patients in the OMS721-TMA-001 study, 0.38 for patients in the EAP, and 0.28 for the pooled patient population from OMS721-TMA-001 and the EAP (all P < .0001). Consistent with the primary analyses, the calculated HR for the sensitivity analyses represent a threefold to fourfold reduction in mortality for narsoplimab-treated patients with a high degree of confidence (P < .0001).

Survival comparison between narsoplimab-treated patients with TA-TMA and the KSCTG TA-TMA group. Forest plot of estimated HR and 95% CIs for the 3 primary comparative survival analyses and corresponding sensitivity analyses. The vertical line represents value at which risk of mortality between the comparator groups would not be different. Values to the left of the line would indicate reduced risk of mortality with narsoplimab treatment and values to the right would indicate increased risk of mortality with narsoplimab treatment. RF, risk factor.

Survival comparison between narsoplimab-treated patients with TA-TMA and the KSCTG TA-TMA group. Forest plot of estimated HR and 95% CIs for the 3 primary comparative survival analyses and corresponding sensitivity analyses. The vertical line represents value at which risk of mortality between the comparator groups would not be different. Values to the left of the line would indicate reduced risk of mortality with narsoplimab treatment and values to the right would indicate increased risk of mortality with narsoplimab treatment. RF, risk factor.

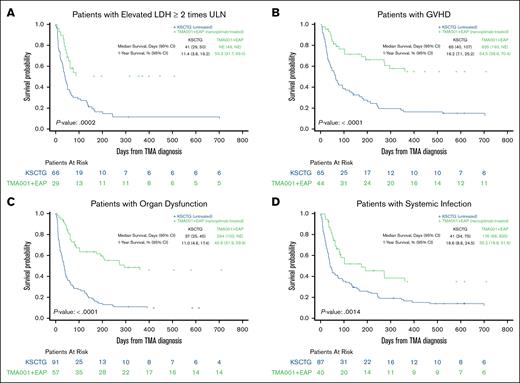

There were notable improvements in survival with treatment by risk factor as well (Figure 4). For patients with elevated LDH of ≥2× ULN, 1-year survival in the KSCTG TA-TMA cohort was 11.4% vs 50.3% for the narsoplimab-treated group (P = .0002). For additional subgroups, 1-year survival for the KSCTG TA-TMA vs the narsoplimab-treated cohort was 16.2% vs 54.5% for acute GVHD (P < .0001), 11.0% vs 45.9% for organ dysfunction (combined for renal, pulmonary, and neurological; P < .0001), and 16.6% vs 35.2% for systemic infection (P = .0014). Similarly, median OS was better in the narsoplimab-treated cohort than for the control group across all subgroups examined, including LDH of ≥2× ULN, acute GVHD, organ dysfunction, and systemic infection (Figure 4).

Survival curves by risk factor subgroup. Median and 1-year survival stratified by risk factor. (A) LDH of ≥2× ULN. (B) Acute GVHD of grade 2 to 4. (C) Organ dysfunction, combined for renal, neurological, and pulmonary. (D) Systemic infection. NE, not evaluated.

Survival curves by risk factor subgroup. Median and 1-year survival stratified by risk factor. (A) LDH of ≥2× ULN. (B) Acute GVHD of grade 2 to 4. (C) Organ dysfunction, combined for renal, neurological, and pulmonary. (D) Systemic infection. NE, not evaluated.

Discussion

Robust comparative statistical analyses of 3 cohorts of high-risk TA-TMA, 2 treated with narsoplimab and 1 well-matched untreated control group, demonstrate that narsoplimab treatment results in significantly improved survival with a threefold to fourfold decreased risk of mortality. This survival benefit was evident despite the pooled narsoplimab cohorts being more enriched with organ dysfunction than the untreated cohort. The larger sample size of pooled narsoplimab-treated patients allowed meaningful analyses of treated vs untreated patients in subgroups of patients with high-risk factors for poor prognosis, including LDH elevation of ≥2× ULN, acute GVHD of grade 2 to 4, organ dysfunction, or systemic infection, further illustrating a survival benefit with treatment. Collectively, these data further corroborate the primary results reported for OMS721-TMA-001, which also demonstrated a positive effect of narsoplimab in severe TA-TMA.23

The KSCTG TA-TMA group was selected as the optimal data set for comparison for several reasons. Given the rarity of TA-TMA and the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria and treatment approaches, consistent patient data capture and diagnosis verification have been challenging in larger classic registries such as the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research and European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. For patients identified as having developed TA-TMA by their treating physicians in the KSCTG registry, KSCTG researchers went back to those physicians, requested and collected extensive additional information on date of TMA diagnosis, diagnostic and prognostic criteria for TA-TMA, and TA-TMA–related treatment information, data not systematically collected in other transplant registries. KSCTG researchers subsequently confirmed the diagnosis of TA-TMA across these patients.34 Furthermore, given the pathophysiology of TA-TMA and the universal disease characteristics, which do not differ across regions or ethnic groups, the features and outcomes observed in Japanese patients are comparable with those typically observed in patients receiving HCT in Europe or North America. The data demonstrating a high degree of consistency in the presence of risk factors for poor prognosis, in particular organ dysfunction, provide further evidence of the suitability of the KSCTG patients with TA-TMA as a control group for the narsoplimab-treated patients. As such, the KSCTG TA-TMA cohort is the most appropriate external control group for comparison of survival in narsoplimab-treated patients with that in untreated patients with TA-TMA.

To date, there are few studies that have applied the International Harmonized Criteria for TA-TMA diagnosis and prognosis to patients other than children. One retrospective and 1 ongoing prospective study have both shown that patients who meet the criteria for high-risk TA-TMA and/or have severe disease have a higher risk of mortality than patients who meet criteria for standard risk.6,36 Particularly, patients with higher-grade acute GVHD, end-organ dysfunction, or infection have a poor prognosis for survival.6,36 In the recent retrospective study by Acosta-Medina et al, organ dysfunction was identified as the most consequential high-risk factor for poor prognosis and was associated with a 1-year survival of <25%; this strong association between organ dysfunction and reduced survival was confirmed in a multivariable analysis.6 Although organ dysfunction in the Acosta-Medina study was present in only 35% of patients, it was present in 96% of the narsoplimab-treated OMS721-TMA-001 population, 83% of EAP patients treated with narsoplimab, and 79% in the KSCTG cohort. In addition, in study OMS721-TMA-001, all patients had at least 2 of the consensus high-risk factors associated with poor prognosis, further highlighting the poor prognosis of the groups and the low likelihood of survival without intervention. The comparisons between narsoplimab-treated groups and the untreated controls demonstrate a clear difference in survival outcomes, including in patients with acute GVHD of grade 2 to 4 and organ dysfunction.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the analysis is a retrospective post hoc comparison between a single-arm trial plus an observational study and an external control group. Additionally, a difference between the KSCTG cohort and the narsoplimab-treated groups is that umbilical cord blood was the stem cell source for ∼40% of the comparator group, whereas the primary source for the narsoplimab-treated patients was peripheral blood stem cells. This difference, however, is not expected to affect survival outcomes based on research that shows that, across bone marrow transplants and umbilical cord blood transplants, there were no differences in overall mortality (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.59-1.79), relapse rates (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.43-1.27), or nonrelapse mortality (HR, 1.68; 95% CI 0.53-5.33) when each center’s experience with cord blood transplants was taken into account.37 A third potential limitation is that the EAP data represent real-world clinical practice, which can vary considerably compared with a controlled clinical trial. Consequently, the criteria used for TA-TMA diagnosis and how narsoplimab is dosed are more variable across this patient population than in a prospective clinical trial, and data reporting on variables other than survival and dates of transplant, TA-TMA diagnosis, and treatment start is not as closely monitored. However, the same stringent statistical analysis to account for differences was conducted to ensure that the comparison between the KSCTG TA-TMA group and the EAP patients was appropriate.

Despite the dosing regimens being different for the EAP (2-3 times weekly) and the OMS721-TMA-001 study (once weekly), the median numbers of doses were similar, with the duration in treatment for the EAP cohort being slightly shorter. Both dosing regimens were similarly effective, and neither was associated with a safety signal of concern, suggesting that dosing frequency should be determined by the treating physician based on patient response.

The absence of any concerning safety signal in patients with TA-TMA treated with narsoplimab,23,38 consistent with no observed safety signal across ∼650 patients in the narsoplimab development program (Omeros Corporation, unpublished data, May 2025), adds to the already observed safety of MASP-2 inhibition. In contrast, compared with a healthy cohort, complement C5 inhibition confers a 1000- to 2000-fold increase in Neisseria meningitis incidence despite receipt of meningococcal vaccine.39 Given the degree of immune suppression after HCT, infections are an increasing concern with respect to TA-TMA treatment strategies. One study of 15 adults with TA-TMA reported resolution of hematologic manifestations after complement C5 inhibition in most patients, although survival was poor due largely to infection-related deaths (70%).40 A recent pediatric study reported an 8.5-fold increased incidence in bacterial bloodstream infections and a sixfold increase in infection-related 1-year mortality in children with TA-TMA treated with eculizumab vs a cohort matched for severe acute GVHD and intensive care unit admissions.41 These studies underscore the need for careful evaluation of safety, particularly in the HCT setting.

Given the severity of TA-TMA and the expanding landscape of complement inhibition strategies, there is also a growing focus on identifying biomarkers that could predict response to certain agents and monitor intended inhibition as well as response. Soluble C5b-9, although not widely available, has been used as a biomarker for the terminal pathway of complement in studies assessing terminal pathway (eg, C5) inhibitors such as eculizumab and ravulizumab with variable predictive and monitoring reliability in TA-TMA.13,42-44 Narsoplimab inhibits the upstream lectin pathway target MASP-2. Thus, soluble C5b-9 has no known utility in monitoring response to narsoplimab.30 Biomarker data were not collected in either patients treated with narsoplimab or in the KSCTG TA-TMA control group, although additional data are needed in the future.

Further studies are under consideration to evaluate the effect of administering narsoplimab to HCT recipients before their development of high-risk TA-TMA. These studies might entail assessing narsoplimab administered to patients early in the development of TA-TMA and/or preventively to HCT recipients. Either of these “temporally upstream” approaches would require larger patient numbers than this study but could provide valuable information on the potential benefits of lectin pathway/MASP-2 inhibition with respect to TA-TMA in HCT recipients. In addition, beyond TA-TMA, other endothelial injury syndromes (eg, veno-occlusive disease, capillary leak syndrome, etc) represent potentially fertile areas for clinical research with MASP-2 inhibitors such as narsoplimab.

In conclusion, in the set of external control analyses reported herein, narsoplimab treatment for TA-TMA demonstrated clear and robust evidence of significant mortality reduction when compared with the well-matched population from the KSCTG control group that did not receive treatment with narsoplimab. These findings are well supported by the analyses conducted to compare OS in narsoplimab-treated patients from the EAP vs OS in the KSCTG TA-TMA group, and are further substantiated by the pooled analysis, as well as the corresponding sensitivity analyses across the different analysis groups. Collectively, these results provide strong evidence of a survival benefit associated with narsoplimab treatment in patients with high-risk TA-TMA.

Acknowledgments

Omeros Corporation supported the study by providing data from the OMS721-TMA-001 clinical trial and the narsoplimab expanded access program. Editorial assistance and figure support were provided by Obsidian Healthcare Group, Ltd.

This research was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 (M.-A.P.). M.L.S. is supported by an American Society of Hematology, the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (AMFDP) award.

Omeros Corporation had a role in providing statistical analysis and programming support and assisted with the preparation and review of the manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: H.M. and Y.A. designed the statistical analysis plan; and all authors reviewed the data and outputs and contributed to the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.-A.P. reports honoraria from Adicet, Allogene, Caribou Biosciences, Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Equilium, Exevir, ImmPACT Bio, Incyte, Kite/Gilead, Merck, Miltenyi Biotec, MorphoSys, Nektar Therapeutics, Novartis, Omeros, OrcaBio, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi, Syncopation, Takeda, VectivBio AG, and Vor Biopharma; serves on data and safety monitoring boards for Cidara Therapeutics and Sellas Life Sciences; reports ownership interests in Omeros and OrcaBio; and has received institutional research support for clinical trials from Allogene, Genmab, Incyte, Kite/Gilead, Miltenyi Biotec, Nektar Therapeutics, and Novartis. R.F.D. reports honoraria and/or institutional research support from Galapagos NV, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Jazz, Merch Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma, Omeros, Roche Diagnostics, Sobi, and Takeda. M.M. has served as a consultant for Adaptive, Amgen, Astellas, BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag Europe, Middle East & Africa (EMEA), Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Medac, Novartis, OncoPep, Pfizer, Sanofi, Stemline Therapeutics, Takeda, and Therakos. A.R. reports honoraria from Astellas, Pfizer, Amgen, Omeros, Novartis, Kite/Gilead, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Celgene-BMS, Janssen, Roche, Incyte, and AbbVie. M.L.S. is a consultant to Omeros and Alexion. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yasuyuki Arai, Department of Hematology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, 54 Shogoin Kawahara-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 6068507, Japan; email: ysykrai@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Yasuyuki Arai (ysykrai@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp).