Background

Diagnosing hematological malignancies in rural sub-Saharan Africa is challenging due to the lack of pathology infrastructures and experienced hematopathologists. Hematological malignancies at the Butaro District Hospital Cancer Center in rural Rwanda are common (third after cervical and breast cancer) and require distinct, disease-directed therapies, which are available in Butaro for many entities. Therefore, accurate and rapid diagnosis is critical for patient care.

Since 2005, a collaboration between Partners In Health (PIH) and several major academic medical centers, including Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), has provided surgical pathology services for healthcare clinics and hospitals in multiple countries, including Rwanda. This has developed over the past decade to include telepathology services.

In an effort to improve hematopathology diagnosis quality and turnaround time, and to build medical/laboratory capacity within Rwanda itself, a telepathology-based collaboration between the single locally based pathologist at Butaro District Hospital Cancer Center (D.R.) and 2 volunteer US-based hematopathologists (E.A.M. and A.G.E.) was established in March 2016.

Butaro District Hospital is a 150-bed contemporary hospital facility located in the Burera district, in the northern part of Rwanda. Opened in 2011, it was built in a collaboration between PIH and the Rwandan Ministry of Health. In addition to basic services, the hospital includes a cancer referral center and expanded laboratory capabilities. Only 1 local pathologist supports the oncology team with diagnosis.

Design

A customized IHC algorithm for the diagnosis of hematological malignancies in Rwanda was shared with the local pathologist.

Challenging hematopathology cases, including those unable to be resolved using the IHC algorithm, were selected by the local pathologist and shared with 2 volunteer US-based hematopathologists for telepathology review (static images taken with a standard digital microscope camera and uploaded on the iPath Web site or whole, scanned digital slides via a GE scanner and application). An e-mail alert was sent to reviewers once a case was uploaded. A clinical summary was also provided.

After review, feedback was provided to the local pathologist through the same channel (if iPath was used) or through a reply to the alert e-mail. If there was disagreement between the 2 reviewers or an inability to render a diagnosis with available IHC, tissue blocks and slides were shipped to BWH via PIH.

Results

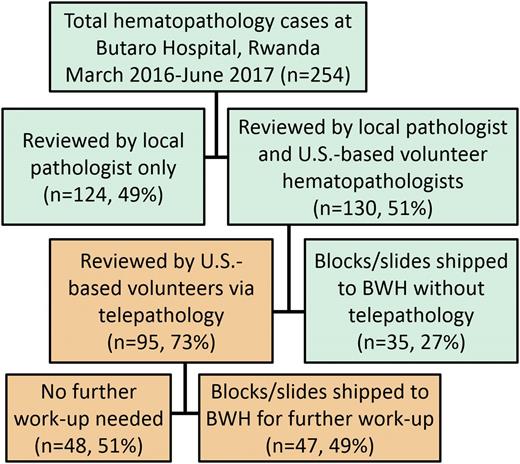

Case workflow. All cases submitted for hematopathology work-up at Butaro District Hospital were reviewed by the local pathologist (D.R.) and then triaged for additional review (51%). The majority (73%) of triaged cases were first reviewed by telepathology: ∼50% were finalized without further work-up, and the other half were shipped to BWH for additional IHC. The remaining triaged cases (27%) were sent directly to BWH when the local pathologist deemed additional molecular or IHC testing would be required for diagnosis.

Case workflow. All cases submitted for hematopathology work-up at Butaro District Hospital were reviewed by the local pathologist (D.R.) and then triaged for additional review (51%). The majority (73%) of triaged cases were first reviewed by telepathology: ∼50% were finalized without further work-up, and the other half were shipped to BWH for additional IHC. The remaining triaged cases (27%) were sent directly to BWH when the local pathologist deemed additional molecular or IHC testing would be required for diagnosis.

Final diagnoses. All patients (n = 254) included 142 males (56%) and 112 females (44%) with a mean age of 30 years (range, 1-75 years). Diagnoses included ∼25% nonneoplastic (e.g. reactive lymphadenitis or staging marrows) and ∼75% neoplastic entities. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) diagnosis was confirmed by BCR-ABL testing performed at BWH or, starting in December 2016, local testing in Rwanda. Remaining entities include plasma cell neoplasm (PCN) (4%), BL (2%), and nonheme malignancy (2%). ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CHL, classical Hodgkin lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Final diagnoses. All patients (n = 254) included 142 males (56%) and 112 females (44%) with a mean age of 30 years (range, 1-75 years). Diagnoses included ∼25% nonneoplastic (e.g. reactive lymphadenitis or staging marrows) and ∼75% neoplastic entities. Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) diagnosis was confirmed by BCR-ABL testing performed at BWH or, starting in December 2016, local testing in Rwanda. Remaining entities include plasma cell neoplasm (PCN) (4%), BL (2%), and nonheme malignancy (2%). ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CHL, classical Hodgkin lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

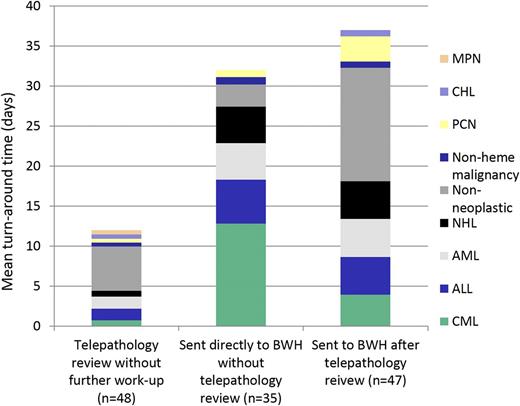

Impact of review method on turnaround time. Cases reviewed by telepathology only had a mean turnaround time (TAT) of 12 days (range, 1-28 days). Once uploaded, volunteers reviewed 92% of cases in <24 hours. Cases sent to BWH had a longer TAT, as expected, due to shipping logistics. Diagnoses of cases reviewed by telepathology or requiring additional work-up at BWH were similar, with the exception of CML (Figure 2).

Impact of review method on turnaround time. Cases reviewed by telepathology only had a mean turnaround time (TAT) of 12 days (range, 1-28 days). Once uploaded, volunteers reviewed 92% of cases in <24 hours. Cases sent to BWH had a longer TAT, as expected, due to shipping logistics. Diagnoses of cases reviewed by telepathology or requiring additional work-up at BWH were similar, with the exception of CML (Figure 2).

Conclusions

Telepathology tools and volunteer US-based hematopathologists are contributing to the improvement of turnaround time for the diagnosis of hematology malignancies in a rural cancer center in Rwanda. Discussing cases also contributes to improving the capacity of the local pathologist in diagnosing hematological malignancies.

Collaboration and professional exchanges between laboratory and medical staff are highly encouraged as a means of building permanent on-site capacity in Rwanda for diagnostic pathology.

Continuing challenges

The mean turnaround time for tissue blocks sent to BWH for IHC review is high (4-5 weeks) due to shipping logistics. Expansion of the arsenal of IHC antibodies at Butaro District Hospital is needed to reduce the number of cases sent to BWH. This will also build the local capacity for diagnosis of hematological malignancies in Rwanda.

Many hematopathology cases are shared by static images rather than whole-slide scanning. This is in part due to the suboptimal image quality/magnification of bone marrow aspirate smears by scanning. In addition, static images allow for rapid acquisition of immunostain images, which generally do not require review of the whole slide.

The instability of the local Internet network in Rwanda contributes to the delay of image upload. This is a major consideration for implementing this tool in other locations.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Danny A. Milner (American Society for Clinical Pathology), Jane E. Brock (Brigham and Women’s Hospital), and Cyprien Shyirambere, Tharcisse Mpunga, Gaspard Muvugabigwi, Irenee Nshimiyimana, Emmanuel Hakizimana, Daniel Orozco, Lauren Greenberg, and Kayleigh Bhangdia (Butaro District Hospital/Partners in Health).

Financial support for immunohistochemistry was provided by the American Society for Clinical Pathology.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: No competing financial interests declared.

Correspondence: Deogratias Ruhangaza, Ministry of Health, Butaro Hospital, Butaro, Rwanda; e-mail: deoruhangaza@gmail.com.