Key Points

AICC has been used since 1977 to control bleeding in patients with hemophilia with inhibitors.

AICC is associated with a low incidence of TEEs, especially when administered prophylactically.

Abstract

Anti-inhibitor coagulant complex (AICC), an activated prothrombin complex concentrate, has been available for the treatment of patients with inhibitors since 1977, and thromboembolic events (TEEs) have been reported after infusion of AICC in patients with congenital or acquired hemophilia. With the aim of estimating the TEE incidence rate (IR) related to AICC exposure in these patients, a systematic review of the literature was carried out in Medline, according to PRISMA guidelines, from inception date to March 2017. The IR of TEEs was estimated through a meta-analytic approach by using a generalized linear mixed model based on a Poisson distribution. Thirty-nine studies were included (1980-2016). Overall, 46 TEEs were reported; of these, 13 were reported as disseminated intravascular coagulations, 11 as myocardial infarctions, and 3 as thrombotic cerebrovascular accidents. The pooled TEE IR was 2.87 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.32-25.40) per 100 000 AICC infusions (5.42 in retrospective studies [95% CI, 0.92-31.82]; 1.09 in prospective studies [95% CI, 0.01-238.77]). The TEE rate was 5.09 (95% CI, 0.01-1795.60) per 100 000 AICC infusions administered on demand, whereas no TEEs were reported with prophylaxis. Interestingly, the estimated IR in patients with congenital hemophilia was <0.01 per 100 000 infusions. These findings provide robust evidence of safety of AICC over almost 40 years of published studies.

Introduction

The development of factor VIII (FVIII) inhibitory antibodies is a major challenge in the treatment of hemophilia, because it hinders FVIII replacement for the treatment and prevention of bleeding events.1 Two products are currently available to control bleeding in patients with inhibitors: anti-inhibitor coagulant complex (AICC), an activated prothrombin complex concentrate (FEIBA [FVIII inhibitor bypassing activity] NF; Shire, Lexington, KY) and recombinant activated factor VII (NovoSeven; Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark). Both agents have shown similar efficacy, with some patients responding better to 1 product than to the other.2 Both agents have been associated with the development of thromboembolic events (TEEs).3

AICC has been used for >40 years to control bleeding in patients with hemophilia with high-titer inhibitors. It is a plasma-derived concentrate that contains various prothrombin complex coagulation factors, in their zymogenic and enzymatic forms, and natural anticoagulant factors in a hemostatic balance.4

The aim of this study was to estimate the TEE incidence rate (IR) in patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors or acquired hemophilia exposed to AICC, using a meta-analytic approach based on published scientific literature.

Methods

We performed a literature search in MedLine using PubMed from its inception date to 23 March 2017 using the following terms: “hemophilia A,” “hemophilia B,” “blood coagulation factors,” “FEIBA,” and “CS849DUN3M” (ie, FEIBA US Food and Drug Administration registration number). The full research string was: (((“hemophilia A” [MeSH Terms] OR “hemophilia B” [MeSH terms] OR (“haemophilia A” [tiab] OR “hemophilia A” [tiab] OR “haemophilia B” [tiab] OR “hemophilia B” [tiab])) AND “blood coagulation factors” [MeSH terms] AND (“FEIBA” [tiab] OR “FEIBA” [supplementary concept] OR “CS849DUN3M” [RN])) NOT (“case reports” [publication type] OR “letter” [publication type])) NOT (animal [MeSH terms] NOT human [MeSH terms]). For the sake of completeness, we further reviewed the references of all relevant retrieved articles to identify additional published studies. Prospective and retrospective, interventional and noninterventional studies on patients with hemophilia A or B with inhibitors or with acquired hemophilia treated with AICC reporting safety data were included in the meta-analysis.

Two of the authors (M.R. and P.A.C.) independently evaluated eligibility of all the studies retrieved from the electronic literature search. Two other reviewers (A.G. and R.C.) were also involved to reach consensus in case of disagreement.

For each included study, we extracted the following data: first author last name, publication year, geographic area of the study, study design (prospective or retrospective, interventional or noninterventional), hemophilia type (A or B, congenital or acquired), treatment modality (on demand, prophylaxis, or surgery), number of patients treated with AICC and their mean age if reported, number of patients reporting TEEs together with the total number and type of TEEs, and estimated number of AICC infusions.

Exposure to AICC was mandatory to compute the IR of TEEs. If the number of AICC infusions was not detailed in the publication, the number of infusions was estimated according to the treatment modality (on demand, prophylaxis, or surgery) and calculated based on the mean duration of treatment and/or the mean overall dose per kilogram of body weight reported. When not otherwise specified, 2 AICC infusions were assumed for each on-demand bleeding treatment.2,5

Given that TEEs are rare, standard statistical meta-analytic methods cannot be applied. In fact, standard errors from studies reporting 0 TEEs cannot be estimated unless a continuity correction factor is used. To overcome this limitation, we estimated study-specific TEE IRs and their associated 95% exact Poisson confidence intervals (CIs), as well as the pooled TEE IR, through a random-intercept generalized linear mixed model based on a Poisson distribution.6

Stratified analyses according to study design (prospective vs retrospective), publication year (1980-2004, 2005-2010, or 2011-2016), hemophilia type (congenital vs acquired), and treatment modality (on demand, prophylaxis, or surgery) were conducted. A metaregression model was fitted to test for the effect of publication year on the pooled TEE IR.

We performed all analyses with R software (version 3.4.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) through the metarate function of the meta package.7

Results

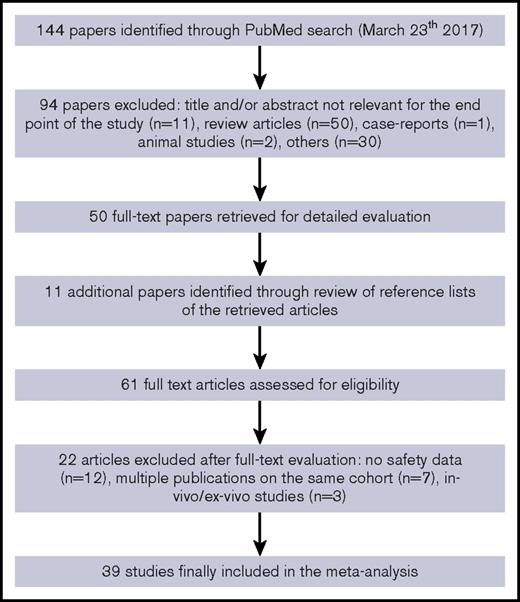

We identified a total of 144 articles through the electronic literature search. After the exclusion of 94 nonrelevant references, 50 articles were fully evaluated for inclusion in the meta-analysis, with other 11 additional articles identified through review of reference lists of retrieved articles. Of the 61 fully evaluated publications, 39 studies with safety data related to the use of AICC in patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors or acquired hemophilia were included in the meta-analysis2,3,5,8-43 (Figure 1).

The studies included2,3,5,8-43 were published from 1980 to 2016 and provided information on safety related to 678 447 AICC infusions (7291 as on-demand treatment,2,5,8-11,15-18,23,28,29,32,33,36,37,39,42,43 77 203 as prophylaxis,13,18,21,26,31,33,39,41,43 3296 in surgery,14,17-20,22,24,27,30,34,38 and 590 657 with unmentioned treatment modalities3,12,25,35,40 ) in >750 patients with inhibitors. Of 39 included studies,2,3,5,8-43 5 were controlled randomized clinical trials,2,5,9,33,39 10 were uncontrolled prospective studies,8,10,11,25,28,31,38,40,42,43 and the remaining 24 were retrospective studies.3,12-24,26,27,29,30,32,34-37,41 A majority of the studies (69%) included only patients with congenital hemophilia,2,5,8-11,13,16,18,20-33,36,37,39,41 and 10% only patients with acquired hemophilia.15,17,40,42 In the remaining 21% of studies involving both patients with acquired and those with congenital hemophilia,3,12,14,19,34,35,38,43 it was not possible to differentiate the number of infusions administered for 1 or the other condition, except in 1 study.

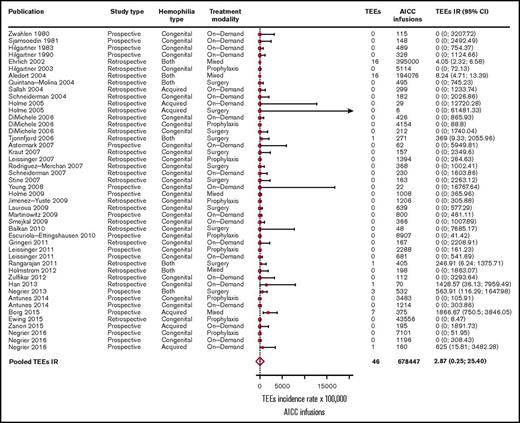

In the overall included 39 studies,2,3,5,8-43 46 TEEs were reported: 13 disseminated intravascular coagulations, 11 myocardial infarctions, 4 pulmonary embolisms, 3 thrombotic cerebrovascular accidents, 3 deep vein thromboses, 3 superficial vein thromboses, 6 unspecified thromboses (unreported locations), and 3 fibrinogen reductions. No thrombotic microangiopathic events were reported. Of the 39 included studies, 31 (79%) reported no TEEs. The pooled TEE estimated IR was 2.87 (95% CI, 0.32-25.40) per 100 000 AICC infusions (Figure 2), with significant heterogeneity among studies (P < .01). When stratifying for retrospective3,12-24,26,27,29,30,32,34-37,41 and prospective studies,2,5,8-11,25,28,31,33,38-40,42,43 35 TEEs per 649 343 AICC infusions (pooled IR, 5.42 per 100 000 infusions; 95% CI, 0.92-31.82) and 11 TEEs per 29 104 AICC infusions (pooled IR, 1.09 per 100 000 infusions; 95% CI, 0.01-238.77) were reported, respectively. We further stratified the studies according to year of publication to evaluate a potential time effect by defining 3 groups of studies: from 1980 to 2004 (10 studies3,8-16 ), 2005 to 2010 (17 studies2,5,17-31 ), and 2011 to March 2017 (12 studies32-43 ). The pooled IRs were 5.46 (95% CI, 3.39-8.87), 0.51 (95% CI, 0-2806.06), and 8.30 (95% CI, 0.49-139.33) per 100 000 AICC infusions, respectively, with no statistically significant effect of publication year on TEE IR as evaluated by the metaregression model (P = .18).

Forest plot for the meta-analysis of TEE IR in patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors or acquired hemophilia exposed to AICC. Results are expressed per 100 000 AICC infusions.

Forest plot for the meta-analysis of TEE IR in patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors or acquired hemophilia exposed to AICC. Results are expressed per 100 000 AICC infusions.

The pooled TEE IR in patients with acquired hemophilia15,17,40,42,43 was 287.79 (95% CI, 31.04-2668.08) per 100 000 AICC infusions, whereas in patients with congenital hemophilia,2,5,8-11,13,16,18,20-33,36,37,39,41,43 it was <0.01 per 100 000 infusions. Moreover, the pooled IR in patients treated on demand with AICC2,5,8-11,15-18,23,28,29,32,33,36,37,39,42,43 was 5.09 (95% CI, 0.01-1795.60) per 100 000 infusions, whereas in patients treated with prophylaxis,13,18,21,26,31,33,39,41,43 no TEEs were reported.

When considering 11 studies in patients with hemophilia with inhibitors undergoing surgery,14,17-20,22,24,27,30,34,38 5 TEEs were reported (Table 1), with a pooled IR of 112.03 (95% CI, 24.66-509.08) per 100 000 AICC infusions.

Description of 5 thromboembolic events reported in 4 patients who had undergone surgery

| Reference . | Study type . | Type of hemophilia . | Procedure type . | AICC dose . | TEE . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | Observational retrospective | Congenital hemophilia A | Major sigmoidectomy | 104 U/kg per day × 13 d | Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction | |

| 34 | Observational retrospective | Congenital hemophilia A | Hernia repair | 158 U/Kg per day × 7 d | Numerous cerebral infarcts | Patient seemed confused after 6 d from surgery, and at day 7, he was agitated with expressive dysphasia. The symptoms resolved within 2 mo. |

| 38 | Observational prospective | Not reported (congenital or acquired hemophilia A) | Total hip replacement | Not reported | DVT in the brachial vein | Treatment with FEIBA was stopped, and the patient did not receive any specific anticoagulant therapy. Three days later, ultrasonographic analysis revealed that the DVT had resolved, but the SVT persisted. When ultrasonography was repeated 5 d later, no further progression was observed in the SVT, and the swelling had resolved. The patient resumed treatment with FEIBA and did not experience any additional thrombotic complications. |

| SVTs in the basilic and cephalic veins of the left arm | ||||||

| 38 | Observational prospective | Not reported (congenital or acquired hemophilia A) | Moderate-risk surgery | Not reported | Clot in an arteriovenous fistula | In this instance, FEIBA administration was permanently discontinued, and heparin (IV) was administered throughout the night, after which the patient recovered completely. A tranexamic acid-soaked gauze, applied locally to the patient’s hand, was unlikely to have contributed to thrombosis in this instance. |

| Reference . | Study type . | Type of hemophilia . | Procedure type . | AICC dose . | TEE . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | Observational retrospective | Congenital hemophilia A | Major sigmoidectomy | 104 U/kg per day × 13 d | Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction | |

| 34 | Observational retrospective | Congenital hemophilia A | Hernia repair | 158 U/Kg per day × 7 d | Numerous cerebral infarcts | Patient seemed confused after 6 d from surgery, and at day 7, he was agitated with expressive dysphasia. The symptoms resolved within 2 mo. |

| 38 | Observational prospective | Not reported (congenital or acquired hemophilia A) | Total hip replacement | Not reported | DVT in the brachial vein | Treatment with FEIBA was stopped, and the patient did not receive any specific anticoagulant therapy. Three days later, ultrasonographic analysis revealed that the DVT had resolved, but the SVT persisted. When ultrasonography was repeated 5 d later, no further progression was observed in the SVT, and the swelling had resolved. The patient resumed treatment with FEIBA and did not experience any additional thrombotic complications. |

| SVTs in the basilic and cephalic veins of the left arm | ||||||

| 38 | Observational prospective | Not reported (congenital or acquired hemophilia A) | Moderate-risk surgery | Not reported | Clot in an arteriovenous fistula | In this instance, FEIBA administration was permanently discontinued, and heparin (IV) was administered throughout the night, after which the patient recovered completely. A tranexamic acid-soaked gauze, applied locally to the patient’s hand, was unlikely to have contributed to thrombosis in this instance. |

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; SVT, superficial vein thrombosis.

Discussion

In summary, the overall pooled IR was lower than 3 TEEs per 100 000 AICC infusions, confirming previous figures reported in smaller and retrospective cohorts.3,12 Stratified analysis showed low TEE incidence in patients with congenital hemophilia compared with those with acquired hemophilia. This finding can probably be explained by the potential presence of other thrombotic risk factors in patients with acquired hemophilia A.44-46 Interestingly, no TEEs were reported during prophylaxis with AICC (ie, repeated AICC exposure for long periods of time with the consequent supernormal levels of factor X and prothrombin and increased thrombin generation and endogenous thrombin potential).4

To estimate how many AICC infusions to which a single patient with hemophilia with inhibitors would be exposed during his or her lifetime, we applied the prophylactic and on-demand regimens reported in the Pro-FEIBA clinical trial33 to a time horizon of 70 years. We estimated that a patient treated with AICC prophylaxis would receive in his or her lifetime 203 infusions per year (183 for prophylaxis and 20 to manage 10 breakthrough bleeds), corresponding to 14 210 infusions in 70 years of treatment. A patient treated on demand would experience 53 AICC infusions per year to manage 26.2 bleeds (ie, 3710 infusions in 70 years). This information is useful to understand the possible impact of the TEE IR estimated in our analysis.

We chose to include only data from published clinical trials, noninterventional prospective studies, and retrospective studies to obtain reliable information on exposure to AICC, which would allow us to estimate the IR of TEEs according to number of infusions. Case reports and spontaneous reports were not considered unless previously included in published studies, as was the case for the studies by Ehrlich et al12 and Aledort.3 Case reports were not included in the meta-analysis, because they cannot provide a reliable estimate of exposure to AICC, and consequently of the IR of TEEs, being specifically focused on describing a single event without considering all treated patients who did not experience any TEEs.47,48 Because of the nature of these 2 studies by Ehrlich et al12 and Aledort,3 which were based on published and unpublished spontaneously reported TEEs documented through the Baxter BioScience Pharmacovigilance Program and the US Food and Drug Administration MedWatch databases, respectively, we carried out a sensitivity analysis by removing them; the pooled IR then decreased to 1.13 (95% CI, 0.04-35.05).

In conducting a meta-analysis based on published aggregated data without access to individual patient data, we could not address potential confounders or evaluate associated risk factors (eg, ICC dose). A large cohort study or individual patient-level meta-analysis should be performed to adjust the TEE IR for confounders or associated risk factors. However, because congenital and acquired hemophilia are rare diseases, and TEEs occurring in those receiving AICC even rarer, such study designs would require longer times and multicenter collaborations, which can often be difficult and resource demanding. Nevertheless, our analysis showed a higher incidence of TEEs in patients with acquired hemophilia, in whom the potential association between TEEs, age, and comorbidities might play a role, and in those with congenital hemophilia who had undergone surgery.49

Because TEEs are rare, the classic meta-analytic model based on the inverse variance approach could not be fitted. Data were analyzed with a generalized linear mixed model based on a Poisson distribution6 to account for the presence of sparse data, thus avoiding the use of a correction factor for studies reporting 0 events; however, CIs were somewhat wide because of the small number of TEEs reported in the 39 studies included in the meta-analysis.

No thrombotic microangiopathic events were reported. However, a recently published article50 reporting results from the HAVEN 1 clinical trial in patients with hemophilia A and inhibitors treated prophylactically with emicizumab described 5 severe adverse events (2 thromboembolic events and 3 thrombotic microangiopathies), which occurred in 5 of 28 patients to whom AICC was administered as rescue therapy for the treatment of breakthrough bleeds. The reported thrombotic microangiopathies were diagnosed as hemolytic uremic syndromes. Hemolytic uremic syndromes such as those observed in the HAVEN 1 study had never been observed with AICC or published before. Moreover, the overall frequency of TEEs observed in that study (1 event per 13-52 estimated infusions) seems higher than that in any other published study.

In conclusion, our systematic review and meta-analysis of published study data provide a comprehensive and exhaustive estimate of the overall, 40-year thromboembolic safety profile of AICC in patients with hemophilia with inhibitors, showing that AICC is associated with a low incidence of TEEs.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported in part by research funding from Shire, Chicago, IL.

Authorship

Contribution: M.R. and P.A.C. carried out the systematic literature review and meta-analysis; all authors had full access to the data, take responsibility for data integrity and analysis, discussed the results, and contributed to the article preparation; and P.A.C., M.R., and L.G.M. had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.A.C. received a research grant from Baxalta, now part of Shire, and speaking honoraria from Pfizer. L.G.M. reports personal fees from Pfizer and Bayer Healthcare. A.G. and R.C. are employed by Shire. M.R. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Paolo A. Cortesi, Research Centre on Public Health, University of Milan-Bicocca, Via G. Pergolesi 33, 20900 Monza, Italy; e-mail: paolo.cortesi@unimib.it.