Key Points

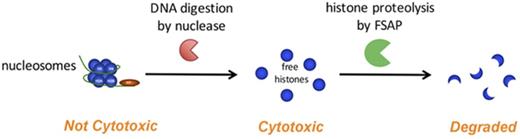

Free histones, not nucleosomes, are cytotoxic and are degraded by FSAP in serum to protect against cytotoxicity.

Free histone H3 was not detectable in sera of septic baboons and patients with meningococcal sepsis.

Abstract

Circulating histones have been implicated as major mediators of inflammatory disease because of their strong cytotoxic effects. Histones form the protein core of nucleosomes; however, it is unclear whether histones and nucleosomes are equally cytotoxic. Several plasma proteins that neutralize histones are present in plasma. Importantly, factor VII–activating protease (FSAP) is activated upon contact with histones and subsequently proteolyzes histones. We aimed to determine the effect of FSAP on the cytotoxicity of both histones and nucleosomes. Indeed, FSAP protected against histone-induced cytotoxicity of cultured cells in vitro. Upon incubation of serum with histones, endogenous FSAP was activated and degraded histones, which also prevented cytotoxicity. Notably, histones as part of nucleosome complexes were not cytotoxic, whereas DNA digestion restored cytotoxicity. Histones in nucleosomes were inefficiently cleaved by FSAP, which resulted in limited cleavage of histone H3 and removal of the N-terminal tail. The specific isolation of either circulating nucleosomes or free histones from sera of Escherichia coli challenged baboons or patients with meningococcal sepsis revealed that histone H3 was present in the form of nucleosomes, whereas free histone H3 was not detected. All samples showed signs of FSAP activation. Markedly, we observed that all histone H3 in nucleosomes from the patients with sepsis, and most histone H3 from the baboons, was N-terminally truncated, giving rise to a similarly sized protein fragment as through cleavage by FSAP. Taken together, our results suggest that DNA and FSAP jointly limit histone cytotoxicity and that free histone H3 does not circulate in appreciable concentrations in sepsis.

Introduction

In inflammatory disease, extensive cell death results in the release of intracellular constituents that may be harmful to the host. Indeed, increased levels of circulating histones and nucleosomes have been found in patients with a range of inflammatory conditions, including sepsis,1-3 traumatic injury and surgery,3-6 cerebral stroke,7 systemic lupus erythematosus,8 and cancer.9,10 In 2009, Xu et al11 demonstrated that histones released by macrophages upon inflammatory challenge were cytotoxic to endothelial cells in vitro. Furthermore, injection of histones induced lethality in mice, whereas anti-histone antibodies lowered mortality in mice with lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemia or after injection with tumor necrosis factor α. Other groups have shown that extracellular histones exacerbate inflammation in a toll-like receptor (TLR)–dependent manner upon kidney or liver injury and during sterile inflammation.12-15 In addition to immune signaling, histones induce direct cytotoxic effects through physical disturbance of the plasma membrane.5 Other extracellular effects of histones include antimicrobial effects,16 particularly when in the form of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs),17,18 coagulation activation,2,19-22 and endothelial activation.23

Histones are highly basic proteins that are strongly conserved throughout evolution and facilitate chromatin compaction by wrapping DNA into a nucleosome complex.24,25 Extracellular histones and nucleosomes may derive from activated macrophages,11 NETs,18 or apoptotic or (secondary) necrotic cells.12,26-30 For apoptotic and necrotic cells, both passive and active mechanisms of chromatin release have been demonstrated. We previously established that the serine protease factor VII–activating protease (FSAP) is activated in serum upon incubation with late apoptotic or necrotic cells and that its activity is required to efficiently release chromatin from these cells into the extracellular environment.28,31 Upon chromatin release from necrotic cells, histone H1 was proteolyzed by FSAP. FSAP circulates as a 78-kDa zymogen at a concentration of 12 µg/mL and is (auto)proteolytically cleaved into a 2-chain form (tcFSAP) upon activation. In addition to activation upon incubation with late apoptotic and necrotic cells, highly charged molecules including heparin,32 RNA,33 and purified histones34 have been shown to induce FSAP autoactivation. Furthermore, Yamamichi et al34 showed that purified histone H3 is cleaved by activated FSAP. In vivo, FSAP activation correlated with circulating nucleosomes and disease severity and mortality in patients with inflammatory conditions including severe sepsis, septic shock, and, specifically, meningococcal sepsis.35-37

Because FSAP is activated upon incubation with cytotoxic histones and is able to degrade histone H1 and H3, we aimed to investigate its effects on histone-induced cytotoxicity. Furthermore, given that histones are part of nucleosomes in the nucleus, we aimed to compare the cytotoxicity of free histones and nucleosomes and determine their respective levels in the circulation in inflammatory disease. We demonstrate that histones, but not nucleosomes, were cytotoxic to human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells in vitro and were efficiently proteolyzed by FSAP in serum. Furthermore, we show that nucleosomes, but not free histones, were detectable in the circulation in sepsis.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Calf thymus histones (type II-A), single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) from salmon testes, and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) from herring testes were from Sigma-Aldrich. NuPAGE materials for sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and western blotting, deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) mix, and Poros HS were from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Human recombinant activated protein C (APC; drotrecogin alfa) was from Eli Lilly. All other chemicals were of laboratory grade and from Sigma-Aldrich or Merck Millipore.

Rat monoclonal antibody anti-mouse κ light chain conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and mouse monoclonal antibodies anti–histone H3, biotinylated antinucleosome F(ab)2 fragments, (biotinylated) anti-FSAP antibodies, anti–α2-antiplasmin (anti-AP), anti-dsDNA, and anti–interleukin-6 were prepared at our department.35,38 tcFSAP was purified from serum as described.28 The production and purification of recombinant FSAP-R313Q (rFSAP) have been described in detail.39

Nucleosomes were purified from Jurkat cells as previously described.40 All histones including H1 were present in our preparation. The protein concentration was 350 µg/mL, as determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay, and the DNA concentration was 320 µg/mL, as determined by absorbance at 260 nm. The final product contained ∼350 000 AU/mL nucleosomes in our enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Sera and plasma

Sera and plasma were obtained from healthy donors at Sanquin Blood Supply (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and handled according to Dutch regulations for the use of patient material, with institutional medical ethical committee approval and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Baboon sera were obtained from the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation with animal care and use committee approval, as detailed previously.41 Sera from patients with menigococcal sepsis were obtained at the Erasmus Medical Centre Rotterdam with institutional approval by the local medical ethical committee, as detailed previously.35 The characterization of FSAP-deficient serum was previously described.27

Sera were obtained from baboons 480 minutes after challenge with Escherichia coli and from patients with meningococcal disease as previously described.35,41

To deplete FSAP from healthy donor serum, anti-κ light chain antibody (RM19; Sanquin) coupled to cyanogen bromide–activated sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) was incubated with 50 µg of anti-FSAP or anti–interleukin-6.8. After washing, overnight incubation with 1 mL of healthy donor serum followed.

Cytotoxicity assays

HEK293 cells and ECRF24 cells were cultured in Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium (BioWhittaker), supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS; Bodinco), 100 U/mL of penicillin (Invitrogen), 100 µg/mL of streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 50 µM of β-mercaptoethanol. The culture medium of ECRF24 cells additionally contained 20 µg/mL of transferrin, 10 U/mL of heparin, and 2.5 ng/mL of basic fibroblast growth factor. Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Lonza) were cultured in endothelial cell growth medium 2 (Lonza), with 2% FCS and vascular endothelial growth factor. All cells were maintained in a 5% carbon dioxide humidified culture incubator at 37°C.

Cells (25 000 per well) were seeded in 200 µL of culture medium in 96-well plates overnight. Histones were preincubated with appropriate reagents (FSAP, serum, ssDNA, dsDNA, or dNTP) in FCS-free Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium for 1 hour at 37°C. Purified nucleosomes were preincubated with or without 5000 U/mL of benzonase for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by incubation with or without activated rFSAP for 1 hour at 37°C. Thereafter, 180 µL of medium was replaced with 80 µL of stimulus to a final concentration of 12.5 to 100 µg/mL of histone/ssDNA/dsDNA/dNTP, 100 µg/mL of nucleosome (protein content), 20 nM of FSAP, or 0.6% to 5% serum. After 24 hours, control wells were treated with 0.1% saponin (Calbiochem) to permeabilize cells. To determine lactate dehydrogenase release using a cytotoxicity detection kit (Roche), 50 µL of supernatant was removed. To determine cell viability, we added 1.4 mg/mL of thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide to the wells. After overnight incubation, 10% SDS was added and the absorbance read at 570 and 690 nm.

Analysis of histone and nucleosome degradation

To investigate histone degradation, 100 µg/mL of histones (∼7 µM) were incubated with 12.5 to 100 nM of tcFSAP, rFSAP, inactive rFSAP, or rAPC, for 1 hour at 37°C. To determine histone degradation in serum or plasma, 125 µg/mL of (biotinylated) histones were incubated with 1.5% to 50% serum or plasma for 1 hour at 37°C. To investigate nucleosome degradation, purified nucleosomes (100 µg/mL of protein content) were preincubated with or without 5000 U/mL of benzonase for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by incubation with serum or 20 nM of tcFSAP for 1 hour at 37°C. Samples were separated on a 12% gel and histone and nucleosome degradation products visualized with Silverquest (Invitrogen) or on western blot with primary antibodies against histone H3 (0.4 µg/mL) or against FSAP (1 µg/mL) and subsequent incubation with 0.5 µg/mL of RM19-HRP or streptavidin HRP. To analyze DNA digestion, nucleosomes were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL of proteinase K in 0.5% SDS at 50°C for 1 hour, and DNA fragments were assessed on 1.5% agarose gel using GelRed (Biotium).

Immunoprecipitation of nucleosomes and free histones

Sera were adjusted to pH 9.5 with sodium hydrogen carbonate buffer with EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche) and incubated with Poros HS resin for 4 hours at room temperature to precipitate all histones. Alongside, sera (or DNA-histone complexes) were incubated for 1 hour with anti-dsDNA antibody coupled to cyanogen bromide–activated sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare). After centrifugation, the sepharose was collected and the supernatant incubated with Poros HS resin for 4 hours at room temperature to precipitate remaining free histones. Proteins precipitated by Poros HS resin and anti-dsDNA sepharose were separated by SDS-PAGE with immunoblot for H3. As a reference curve for densitometric quantification, calf thymus histones were separated on the same gel.

ELISA

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean values ± standard error of the mean, except for means of <3 values, where ± standard deviation is indicated. Statistical analyses were performed using an unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test or a Bonferroni-corrected analysis of variance in GraphPad Prism 6 software. P < .05 was considered significantly different from the null hypothesis.

Results

FSAP cleaves histones and protects against histone cytotoxicity to HEK293 and cultured endothelial cells

To examine the proteolytic activity of FSAP toward the different histone subtypes, we incubated unfractionated histones from calf thymus with plasma-purified active FSAP and analyzed the appearance of cleavage products by SDS-PAGE. We observed that FSAP efficiently proteolyzed histone subtypes H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 at multiple cleavage sites (Figure 1A). To confirm that the observed proteolytic activity was not the result of an impurity in our plasma-purified FSAP preparation, we used rFSAP, which is inactive and resistant to autoactivation; however, the mutation allows for in vitro activation of FSAP with thermolysin.39 Active rFSAP, but not inactive rFSAP, efficiently proteolyzed histones. For comparison, we incubated histones with rAPC, because it was previously found to cleave histones.11 In our assay, histone proteolysis by FSAP was more efficient than APC-mediated proteolysis (Figure 1B).

Active FSAP proteolyzes all histone subtypes and provides protection against histone-induced cytotoxicity in HEK293 cells. (A-B) Calf thymus histones (100 µg/mL or ∼7 µM) were incubated with different concentrations of plasma-purified active FSAP (12.5, 25, 50, or 100 nM) and the same concentrations of active rFSAP (A) or APC (B) at 37°C for 30 minutes to determine proteolysis of the different histone subtypes. Cleavage products were visualized by SDS-PAGE and subsequent silver staining. Normal plasma concentration of FSAP: ∼185 nM. Arrows indicate the different histone subtypes. (C-D) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 20 nM of plasma-purified active FSAP, active rFSAP, or inactive rFSAP for 30 minutes before their addition to HEK293 cells and overnight incubation. To determine cytotoxicity, lactate dehydrogenase levels were quantified in the supernatant (C), whereas the viability of the cells was assessed by conversion of thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (D). Cytotoxicity is expressed as a percentage of cytotoxicity induced by 0.1% saponin, and cell viability is expressed as a percentage of untreated cells. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean obtained from 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 (calculated using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test). inact, inactive.

Active FSAP proteolyzes all histone subtypes and provides protection against histone-induced cytotoxicity in HEK293 cells. (A-B) Calf thymus histones (100 µg/mL or ∼7 µM) were incubated with different concentrations of plasma-purified active FSAP (12.5, 25, 50, or 100 nM) and the same concentrations of active rFSAP (A) or APC (B) at 37°C for 30 minutes to determine proteolysis of the different histone subtypes. Cleavage products were visualized by SDS-PAGE and subsequent silver staining. Normal plasma concentration of FSAP: ∼185 nM. Arrows indicate the different histone subtypes. (C-D) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 20 nM of plasma-purified active FSAP, active rFSAP, or inactive rFSAP for 30 minutes before their addition to HEK293 cells and overnight incubation. To determine cytotoxicity, lactate dehydrogenase levels were quantified in the supernatant (C), whereas the viability of the cells was assessed by conversion of thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (D). Cytotoxicity is expressed as a percentage of cytotoxicity induced by 0.1% saponin, and cell viability is expressed as a percentage of untreated cells. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean obtained from 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 (calculated using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test). inact, inactive.

Next, we investigated the effect of FSAP on histone-induced cytotoxicity in vitro. Whereas histones showed strong cytotoxic effects on HEK293 cells in both a lactate dehydrogenase (Figure 1C) and thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide assay (Figure 1D), preincubation of histones with FSAP completely neutralized these cytotoxic effects. Similar to plasma-purified FSAP, active, but not inactive, rFSAP was able to protect against cell death. These results were confirmed using ECRF-24 cells (an HUVEC line) and primary HUVECs (supplemental Figure 1).

It has been reported that histones catalyze autoactivation of FSAP.34 To establish that endogenous FSAP in serum is activated upon adding exogenous histones, we incubated sera from 3 healthy donors with unfractionated histones and detected complexes of activated FSAP with AP, a known serpin of FSAP present in plasma, by ELISA.35 Upon incubation of serum with histones, we found significantly increased levels of FSAP-AP complexes, indicating that FSAP activation had occurred (Figure 2A). Subsequently, we incubated HEK293 cells with histones that had been preincubated with sera from 3 healthy donors or with FSAP-deficient serum.27 Upon increasing the serum concentration, the cytotoxicity of the added histones was greatly reduced (Figure 2B-C). The addition of FSAP-deficient serum also reduced cytotoxicity, but higher concentrations of serum were needed compared with sera from healthy donors. Depleting FSAP from healthy donor serum (Figure 2D) caused a similarly increased sensitivity to histone cytotoxicity as found in FSAP-deficient serum, whereas mock depletion had no effect (Figure 2E). To verify whether histones in this assay had been proteolyzed by FSAP, we visualized histone H3 cleavage on immunoblot. We observed that histone H3 was degraded in healthy donor serum in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas histone H3 proteolysis was absent in FSAP-deficient and FSAP-depleted serum (Figure 2F). Moreover, degradation of histones other than histone H3 was observed on blot when biotinylated histones were spiked into serum (Figure 2G). To investigate histone cleavage and the inactivation of FSAP by serpins in time, we incubated histones with serum and detected FSAP-AP complexes at 0 to 30 minutes, while histone H3 degradation was assessed in parallel by immunoblot (Figure 2H). Both histone degradation of a nearly 80-fold molar excess of histones over FSAP and the inactivation of FSAP occurred within 2 minutes; these were absent in FSAP-depleted serum. Finally, we observed that histone proteolysis was equally efficient in serum and plasma (Figure 2I) and therefore did not result from proteases activated during serum preparation.

FSAP in serum is activated upon incubation with histones and protects against histone-induced cytotoxicity in HEK293 cells through histone proteolysis. (A) Serum samples (50%) of 3 healthy donors (HDs) were incubated with 100 µg/mL of calf thymus histones for 1 hour at 37°C. As a readout for subsequent activation (and inactivation) of FSAP in serum, complexes of FSAP with AP, a known serpin of FSAP, were determined by ELISA. (B-C) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated in the presence of different concentrations (0.6% to 5%) of HD serum or FSAP-deficient serum at 37°C for 30 minutes before their addition to HEK293 cells and overnight incubation. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in the supernatant were quantified to determine cytotoxicity (B), whereas the viability of the cells was assessed by conversion of thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (C). (D) FSAP was depleted from HD serum using an anti-FSAP antibody, and mock depletion is shown as a control. (E) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 0.6% to 5% FSAP-depleted (D) or mock-depleted serum, and the cytotoxicity for HEK293 cells was determined by LDH release. (F) Histone proteolysis after incubation in the presence of 1.3%, 2.5%, and 5% serum was determined in the samples from panel E by immunoblotting for histone H3. (G) Biotinylated histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 5% to 20% serum, mock-depleted serum, or FSAP-depleted serum, and histone proteolysis was assessed using streptavidin HRP. (H) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 50% HD serum or FSAP-depleted serum, and FSAP-AP complexes were determined at t = 0 to 30 minutes, whereas histone H3 degradation (inset) was assessed by immunoblotting for histone H3. FSAP-AP complexes were normalized to t = 30 minutes. (I) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 50% serum or plasma for 0 to 30 minutes, and histone H3 degradation was assessed by immunoblotting for histone H3. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 (calculated using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test). def., deficient; depl., depleted.

FSAP in serum is activated upon incubation with histones and protects against histone-induced cytotoxicity in HEK293 cells through histone proteolysis. (A) Serum samples (50%) of 3 healthy donors (HDs) were incubated with 100 µg/mL of calf thymus histones for 1 hour at 37°C. As a readout for subsequent activation (and inactivation) of FSAP in serum, complexes of FSAP with AP, a known serpin of FSAP, were determined by ELISA. (B-C) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated in the presence of different concentrations (0.6% to 5%) of HD serum or FSAP-deficient serum at 37°C for 30 minutes before their addition to HEK293 cells and overnight incubation. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in the supernatant were quantified to determine cytotoxicity (B), whereas the viability of the cells was assessed by conversion of thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (C). (D) FSAP was depleted from HD serum using an anti-FSAP antibody, and mock depletion is shown as a control. (E) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 0.6% to 5% FSAP-depleted (D) or mock-depleted serum, and the cytotoxicity for HEK293 cells was determined by LDH release. (F) Histone proteolysis after incubation in the presence of 1.3%, 2.5%, and 5% serum was determined in the samples from panel E by immunoblotting for histone H3. (G) Biotinylated histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 5% to 20% serum, mock-depleted serum, or FSAP-depleted serum, and histone proteolysis was assessed using streptavidin HRP. (H) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 50% HD serum or FSAP-depleted serum, and FSAP-AP complexes were determined at t = 0 to 30 minutes, whereas histone H3 degradation (inset) was assessed by immunoblotting for histone H3. FSAP-AP complexes were normalized to t = 30 minutes. (I) Histones (100 µg/mL) were incubated with 50% serum or plasma for 0 to 30 minutes, and histone H3 degradation was assessed by immunoblotting for histone H3. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 (calculated using an unpaired 2-tailed Student t test). def., deficient; depl., depleted.

Nucleosomes and histone-DNA complexes are not cytotoxic to HEK293 cells

Both free histones and nucleosomes have been found to circulate in inflammatory disease.5 It is not clear, however, how the cytotoxicity of free histones compares to that induced by histones in the form of nucleosomes. To investigate the cytotoxicity of nucleosomes, we purified nucleosomes from Jurkat cells (supplemental Figure 2 shows protein and DNA analyses of the purified product).42 In contrast to free histones, purified nucleosomes were not cytotoxic to HEK293 cells (Figure 3A). To corroborate that the histones in these nucleosomes were cytotoxic, we digested the DNA in nucleosomes with benzonase nuclease before the addition to HEK293 cells. Indeed, histones released from the purified nucleosomes by DNA digestion were cytotoxic. As expected, subsequent incubation of benzonase-treated nucleosomes with FSAP reduced cytotoxicity. We visualized DNA on agarose gel (Figure 3B) and assessed histones using SDS-PAGE, respectively (Figure 3C). DNA in nucleosomes was fully digested by benzonase. Of note, limited histone cleavage was observed upon incubation of nucleosomes with FSAP. However, upon DNA digestion with benzonase, FSAP proteolyzed the released histones with high efficiency.

Histones in the form of a nucleosome complex are not cytotoxic unless released by DNA digestion. (A) HEK293 cells were incubated overnight with histones (100 µg/mL) or nucleosomes (100 µg/mL), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was determined as a readout for cytotoxicity. Cytotoxicity was expressed as a percentage of cytotoxicity induced by 0.1% saponin. Nucleosomes or histones were preincubated with buffer and 20 nM of rFSAP, or 5000 U/mL of benzonase nuclease or a combination of both for 30 minutes at 37°C. (B-C) Nucleosomes that had been preincubated with benzonase nuclease, rFSAP, or a combination of both for the experiment in panel A were separated on agarose gel and DNA visualized with dsRED (B) or on SDS-PAGE with instant blue staining for protein (C). The gels shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Arrows indicate the different histone subtypes and benzonase. *Indicates a 13-kDa cleavage product. (D) HEK293 cells were incubated overnight with histones (100 µg/mL) that had been preincubated with 0 to 100 µg/mL of dNTPs, ssDNA, or dsDNA for 30 minutes at 37°C. LDH release was determined as a readout for cytotoxicity. The cytotoxicity induced with 100 µg/mL of histones was defined as 100%. (E) Histones (10 µg/mL) were incubated with ssDNA, dsDNA (10 µg/mL), or buffer before incubation with sepharose-coupled anti-DNA. Histone H3 was visualized in the immunoprecipitated samples by immunoblotting. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean from 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001 (calculated using a Bonferroni corrected 1-way analysis of variance). IP, immunoprecipitation.

Histones in the form of a nucleosome complex are not cytotoxic unless released by DNA digestion. (A) HEK293 cells were incubated overnight with histones (100 µg/mL) or nucleosomes (100 µg/mL), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release was determined as a readout for cytotoxicity. Cytotoxicity was expressed as a percentage of cytotoxicity induced by 0.1% saponin. Nucleosomes or histones were preincubated with buffer and 20 nM of rFSAP, or 5000 U/mL of benzonase nuclease or a combination of both for 30 minutes at 37°C. (B-C) Nucleosomes that had been preincubated with benzonase nuclease, rFSAP, or a combination of both for the experiment in panel A were separated on agarose gel and DNA visualized with dsRED (B) or on SDS-PAGE with instant blue staining for protein (C). The gels shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Arrows indicate the different histone subtypes and benzonase. *Indicates a 13-kDa cleavage product. (D) HEK293 cells were incubated overnight with histones (100 µg/mL) that had been preincubated with 0 to 100 µg/mL of dNTPs, ssDNA, or dsDNA for 30 minutes at 37°C. LDH release was determined as a readout for cytotoxicity. The cytotoxicity induced with 100 µg/mL of histones was defined as 100%. (E) Histones (10 µg/mL) were incubated with ssDNA, dsDNA (10 µg/mL), or buffer before incubation with sepharose-coupled anti-DNA. Histone H3 was visualized in the immunoprecipitated samples by immunoblotting. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean from 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001 (calculated using a Bonferroni corrected 1-way analysis of variance). IP, immunoprecipitation.

These results suggest that the DNA that wraps the nucleosome core may neutralize the cytotoxic effects of histones. To investigate the effect of DNA on histone cytotoxicity, we coincubated histones with synthetic dNTP, ssDNA, or dsDNA before their incubation with HEK293 cells. Both ssDNA and dsDNA neutralized histone-induced cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner, whereas free dinucleotides were unable to neutralize histone cytotoxicity (Figure 3D). To investigate whether neutralization of histone cytotoxicity is a result of histone binding to DNA, we performed an immunoprecipitation using anti-DNA antibody. Immunoblot revealed the binding of histone H3 and H3 dimers to DNA (Figure 3E). These results provide further in vitro evidence that the interaction of histones with DNA abolishes their cytotoxic effects.

Free histones induce FSAP activation more efficiently than nucleosomes

Because histones mediate FSAP activation in serum and are subsequently proteolyzed by FSAP, we aimed to compare the activation of FSAP in serum using either intact nucleosomes or histones released from nucleosomes through DNA digestion. Purified nucleosomes were preincubated in the presence or absence of benzonase before their addition to healthy donor serum. After incubation, FSAP-AP complexes were determined as readout for FSAP activation. The addition of intact nucleosomes to serum resulted in limited FSAP activation only (Figure 4A). However, histones that had been released from nucleosomes using benzonase efficiently activated FSAP. To investigate whether the activation of FSAP by the released histones also results in histone proteolysis, we incubated both intact nucleosomes and benzonase-incubated nucleosomes with healthy donor serum, FSAP-deficient serum, mock-depleted serum, and FSAP-depleted serum and used immunoblot to determine histone H3 cleavage. Some histone H3 proteolysis was observed upon incubation of nucleosomes with healthy donor serum or mock-depleted serum, giving rise to a 13-kDa cleavage product of histone H3 (Figure 4B). However, no proteolysis of histone H3 was observed upon incubation of nucleosomes with FSAP-deficient or FSAP-depleted serum, although a faint 13-kDa band was detectable in our nucleosome preparation in the absence of serum. In contrast, histones were readily degraded in serum when nucleosome DNA had been digested. This degradation was FSAP dependent, because no histone proteolysis was observed upon incubation with FSAP-deficient or FSAP-depleted serum. We also observed the appearance of the 13-kDa cleavage product upon FSAP-mediated proteolysis of recombinant histone H3.1, which we found was inefficiently cleaved and required high concentrations of FSAP. N-terminal sequencing of the 13-kDa cleavage fragment of histone H3.1 revealed that it was N-terminally truncated, with FSAP cleaving between K27 and S28 (supplemental Figure 3).

Histones efficiently activate FSAP in serum and are subsequently degraded. (A) Nucleosomes (100 µg/mL) were preincubated with or without benzonase nuclease (5000 U/mL) at 37°C for 1 hour to digest nucleosome DNA before incubation with serum (50%) from 5 healthy donors at 37°C for 1 hour. As a readout for activation of FSAP in serum, complexes of FSAP with AP were determined by ELISA. (B) Nucleosomes that had been preincubated with or without benzonase were incubated with increasing concentrations (0% to 40%) of healthy donor serum, FSAP-deficient serum, FSAP-depleted serum, or mock-depleted serum at 37°C for 1 hour. Total histones and nucleosomes present in the samples were precipitated using Poros HS resin and separated by SDS-PAGE, and histone H3 proteolysis was assessed using anti–histone H3 antibody on immunoblot. Data are expressed as mean ± standard of the mean of 3 independent experiments. Representative blots of 3 independent experiments are shown. Arrows indicate intact histone H3 and a cleavage product of histone H3. **P < .01 (calculated using a paired 2-tailed Student t test).

Histones efficiently activate FSAP in serum and are subsequently degraded. (A) Nucleosomes (100 µg/mL) were preincubated with or without benzonase nuclease (5000 U/mL) at 37°C for 1 hour to digest nucleosome DNA before incubation with serum (50%) from 5 healthy donors at 37°C for 1 hour. As a readout for activation of FSAP in serum, complexes of FSAP with AP were determined by ELISA. (B) Nucleosomes that had been preincubated with or without benzonase were incubated with increasing concentrations (0% to 40%) of healthy donor serum, FSAP-deficient serum, FSAP-depleted serum, or mock-depleted serum at 37°C for 1 hour. Total histones and nucleosomes present in the samples were precipitated using Poros HS resin and separated by SDS-PAGE, and histone H3 proteolysis was assessed using anti–histone H3 antibody on immunoblot. Data are expressed as mean ± standard of the mean of 3 independent experiments. Representative blots of 3 independent experiments are shown. Arrows indicate intact histone H3 and a cleavage product of histone H3. **P < .01 (calculated using a paired 2-tailed Student t test).

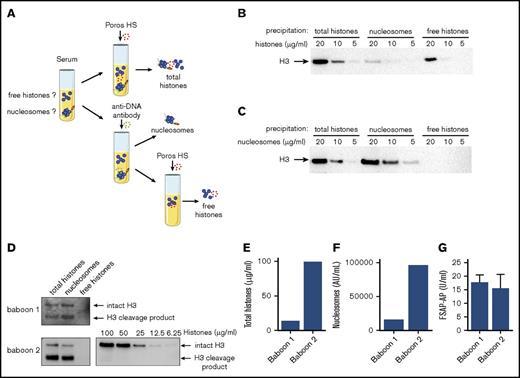

Histone H3 is not detectable in sera of baboons challenged with E coli

Previous studies have revealed that FSAP is activated in various inflammatory diseases.35-37 We therefore wondered whether free histones circulate in sepsis. We set up an assay to specifically precipitate nucleosomes or free histones from serum. We used Poros HS, a cation exchange resin that strongly binds both free histones and DNA-bound histones at high pH, to precipitate all histones present in serum. In parallel, we used an anti-DNA antibody43 coupled to sepharose to specifically precipitate cell-free DNA and nucleosomes, but not free histones. Subsequently, in a second step, the nucleosome-depleted sample was incubated with Poros HS to precipitate any remaining free histones (Figure 5A). The 3 fractions were then analyzed on immunoblot for the presence of histone H3. To validate our assay, we titrated equal concentrations of either histones (Figure 5B) or nucleosomes (Figure 5C) into FSAP-deficient serum. Using Poros HS, the total amounts of histones and nucleosomes were precipitated; all histones that were added in the form of nucleosomes were specifically precipitated using the anti-DNA antibody, and added free histones were precipitated thereafter using Poros HS in the second step. We determined the sensitivity of our assay to detect nucleosomes or histone H3 at ∼5 and ∼10 µg/mL, respectively. We then analyzed serum samples obtained from baboons that had been challenged with E coli in our assay.41 All histones present in the baboon sera were equally well immunoprecipitated by Poros HS and the anti-DNA antibody beads, whereas free histones were not detected after depletion of nucleosomes (Figure 5D). We quantified total histone H3 levels by densitometry using a histone titration on the same immunoblot (Figure 5E). These levels corresponded to the serum nucleosome levels as determined by ELISA (Figure 5F), because 100 000 U/mL corresponds to ∼100 µg/mL of nucleosomes. Moreover, we detected FSAP-AP complexes in these sera, indicating that FSAP activation had occurred (Figure 5G). To our surprise, histone H3 in these samples migrated at ∼13 kDa, suggesting N-terminal truncation, whereas intact H3 migrates at ∼16 kDa.

Free histones are not detectable in sera of baboons challenged with E coli. (A) Schematic overview of total histone precipitation by Poros HS; nucleosome precipitation by an anti-DNA antibody coupled to sepharose, followed by precipitation of remaining free histones by Poros HS. (B-C) FSAP-deficient serum was spiked with 5 to 20 µg/mL of histones (B) or nucleosomes (C) and incubated with Poros HS, a strong cation exchange resin, to precipitate both histones and nucleosomes. In parallel, similarly spiked samples were incubated with an anti-DNA antibody coupled to sepharose to immunoprecipitate all nucleosomes, but not free histones, before incubation with Poros HS to precipitate the remaining free histones. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the presence of histone H3 in the precipitated samples was determined using anti–histone H3 antibody on immunoblot. (D) The presence of nucleosomes and free histones was analyzed in serum of 2 baboons that had been lethally challenged with E coli. As before, total histones, nucleosomes, or free histones were separated on gel, and histone H3 was visualized (D) and quantified (E) using a histone titration on the same blot as exemplified for baboon 2. (E) Histone levels as determined with densitometric analysis. (F) Nucleosome levels as determined in the sera by ELISA. (G) FSAP-AP levels were determined by ELISA to verify FSAP activation. Blots are representative of 3 independent experiments, except for the baboon samples, which are representative of 2 independent experiments because of limited sample availability. Arrows indicate intact histone H3 or a cleavage product of histone H3.

Free histones are not detectable in sera of baboons challenged with E coli. (A) Schematic overview of total histone precipitation by Poros HS; nucleosome precipitation by an anti-DNA antibody coupled to sepharose, followed by precipitation of remaining free histones by Poros HS. (B-C) FSAP-deficient serum was spiked with 5 to 20 µg/mL of histones (B) or nucleosomes (C) and incubated with Poros HS, a strong cation exchange resin, to precipitate both histones and nucleosomes. In parallel, similarly spiked samples were incubated with an anti-DNA antibody coupled to sepharose to immunoprecipitate all nucleosomes, but not free histones, before incubation with Poros HS to precipitate the remaining free histones. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the presence of histone H3 in the precipitated samples was determined using anti–histone H3 antibody on immunoblot. (D) The presence of nucleosomes and free histones was analyzed in serum of 2 baboons that had been lethally challenged with E coli. As before, total histones, nucleosomes, or free histones were separated on gel, and histone H3 was visualized (D) and quantified (E) using a histone titration on the same blot as exemplified for baboon 2. (E) Histone levels as determined with densitometric analysis. (F) Nucleosome levels as determined in the sera by ELISA. (G) FSAP-AP levels were determined by ELISA to verify FSAP activation. Blots are representative of 3 independent experiments, except for the baboon samples, which are representative of 2 independent experiments because of limited sample availability. Arrows indicate intact histone H3 or a cleavage product of histone H3.

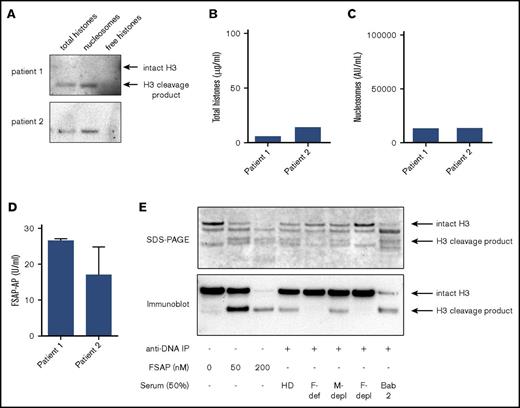

Histone H3 is not detectable in sera of patients with meningococcal sepsis

Next, to confirm these results in human sepsis, we studied sera obtained from patients with meningococcal disease.35 Analogous to results obtained in experimental sepsis in baboons, nucleosomes were present in these sera, but we did not detect free histone H3 (Figure 6A). Again, calculated histone levels in these sera (Figure 6B) corresponded to nucleosome levels (Figure 6C), and FSAP-AP complexes were present (Figure 6D). Once more, we found that histone H3 migrated at ∼13 kDa, suggesting that histone H3 was N-terminally truncated in these precipitated samples. Strikingly, the 13-kDa N-terminally truncated histone H3 was also observed when nucleosomes were incubated with FSAP (Figure 3C) or in healthy donor serum, but not in FSAP-deficient or FSAP-depleted serum (Figure 4B). To confirm that FSAP cleaves H3 in nucleosomes, we incubated purified nucleosomes with FSAP, healthy donor serum, FSAP-deficient serum, mock-depleted serum, and FSAP-depleted serum and compared the cleavage products with nucleosomes precipitated from an E coli–challenged baboon (Figure 5D) by SDS-PAGE and H3 immunoblot. Indeed, we observed that cleavage of H3 in nucleosomes in serum was FSAP dependent (Figure 6E) and that the N-terminal cleavage product was the same size as the H3 cleavage products found in septic baboons.

Free histones are not detectable in the sera of patients with meningococcal sepsis. (A) The presence of nucleosomes and free histones was analyzed in serum of 2 patients with meningococcal sepsis. As before, total histones, nucleosomes, or free histones were immunoprecipitated and separated on gel, and histone H3 was visualized (A) and quantified (B) using a histone titration on the same blot. (B) Histone levels as determined via densitometric analysis. (C) Nucleosome levels as determined in the sera by ELISA (D). FSAP-AP levels were determined by ELISA to verify FSAP activation. Blots of the patient samples are representative of 2 independent experiments because of limited sample availability. (E) Purified nucleosomes were incubated with plasma-purified FSAP (0, 50, or 200 nM), healthy donor serum (HD), FSAP-deficient serum (F-def), mock-depleted serum (M-depl), or FSAP-depleted serum (F-depl; 50%) and were immunoprecipitated from serum using an anti-DNA antibody coupled to sepharose. The cleavage products and the nucleosomes previously immunoprecipitated from a septic baboon serum (Figure 5D baboon 2, lane 2) were separated by SDS-PAGE, and histones were visualized by instant blue staining (upper panel), or histone H3 and its cleavage product were visualized by an anti–histone H3 antibody on immunoblot (lower panel). Arrows indicate intact histone H3 or a cleavage product of histone H3.

Free histones are not detectable in the sera of patients with meningococcal sepsis. (A) The presence of nucleosomes and free histones was analyzed in serum of 2 patients with meningococcal sepsis. As before, total histones, nucleosomes, or free histones were immunoprecipitated and separated on gel, and histone H3 was visualized (A) and quantified (B) using a histone titration on the same blot. (B) Histone levels as determined via densitometric analysis. (C) Nucleosome levels as determined in the sera by ELISA (D). FSAP-AP levels were determined by ELISA to verify FSAP activation. Blots of the patient samples are representative of 2 independent experiments because of limited sample availability. (E) Purified nucleosomes were incubated with plasma-purified FSAP (0, 50, or 200 nM), healthy donor serum (HD), FSAP-deficient serum (F-def), mock-depleted serum (M-depl), or FSAP-depleted serum (F-depl; 50%) and were immunoprecipitated from serum using an anti-DNA antibody coupled to sepharose. The cleavage products and the nucleosomes previously immunoprecipitated from a septic baboon serum (Figure 5D baboon 2, lane 2) were separated by SDS-PAGE, and histones were visualized by instant blue staining (upper panel), or histone H3 and its cleavage product were visualized by an anti–histone H3 antibody on immunoblot (lower panel). Arrows indicate intact histone H3 or a cleavage product of histone H3.

Discussion

Upon cell death, it is unclear in what form histones are released into the extracellular environment. Most methods used to detect histones in serum are unable to discriminate between free histones, DNA-bound histones, or histones as part of a nucleosome complex; thus, their individual contributions to inflammation have remained unexplored. We show that free histone H3 is not detectable in appreciable concentrations in sepsis but is instead part of nucleosomes.

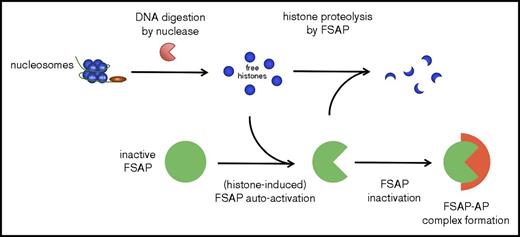

Nucleosomes, in contrast to free histones, were not cytotoxic in our experiments using cultured HEK293 cells. Histones induce cytotoxicity via several mechanisms, among which are disruption of plasma membrane integrity through their highly positive charge and the reported ability to trigger TLR-2, −4, and −9.14-16 The HEK293 cells in our experiments did not express TLRs, indicating that histone cytotoxicity in our system was TLR independent and likely mediated through plasma membrane disturbance. Not surprisingly, many plasma proteins that neutralize histones are highly negatively charged, such as heparin,44 pentraxin-3,45 C-reactive protein,46 and inter-α inhibitor protein.21 DNA may also efficiently neutralize the histone charge, and indeed, analogous to nucleosomes, we showed that both ssDNA and dsDNA neutralized the cytotoxicity induced by histones. In support of our results, it was found that upon infusion of large amounts of nucleosomes in mice, these nucleosomes were efficiently cleared by the liver, and no cytotoxic effects were reported.47 We speculate that the DNA that wraps the nucleosome core protects against histone cytotoxicity through neutralization of the positive charge of histones. However, when histones are released from nucleosomes because of the activity of (circulating) nucleases, we propose that FSAP may serve as an important line of defense against their cytotoxic effects (model provided in Figure 7).

Schematic model of the proposed mechanism by which histones liberated from nucleosomes upon DNA digestion are degraded by FSAP. Nucleosomes are not cytotoxic, but through digestion of nucleosome DNA by circulating nucleases, cytotoxic histones may be liberated. These histones induce the autoactivation of FSAP, and the histones are in turn rapidly degraded by FSAP, which neutralizes their cytotoxicity. FSAP is subsequently inactivated through irreversible complex formation with serin protease inhibitors, including AP.

Schematic model of the proposed mechanism by which histones liberated from nucleosomes upon DNA digestion are degraded by FSAP. Nucleosomes are not cytotoxic, but through digestion of nucleosome DNA by circulating nucleases, cytotoxic histones may be liberated. These histones induce the autoactivation of FSAP, and the histones are in turn rapidly degraded by FSAP, which neutralizes their cytotoxicity. FSAP is subsequently inactivated through irreversible complex formation with serin protease inhibitors, including AP.

Nucleosomes may be released during cell death but may also derive from NETs that are released from neutrophils.17 It was previously demonstrated that NETs are cytotoxic when added to human alveolar epithelial cells and that histones, and not DNA, mediate the observed cytotoxic effects.18 Strikingly, anti-histone antibodies only partly neutralized the cytotoxicity of NETs, presumably because other proteins in NETs also conferred cytotoxicity. Instead, in a study by Kumar et al,48 the cytotoxicity of NETs was completely inhibited by an anti-histone antibody. The size of the chromatin fragments, presence of antimicrobial proteins, and different histone modifications that modulate chromatin condensation, and thus histone exposure, may have influenced NET cytotoxicity. Because injection of anti-histone antibodies had beneficial effects in mouse and baboon sepsis,11,49 and our results suggest that histones circulate as nucleosomes that are not cytotoxic in vitro, other mechanisms must be involved in nucleosome-induced inflammation.

Nucleosomes have been described to activate neutrophils and dendritic cells, driving inflammation.42,50,51 Alternatively, nucleosomes may be modified after entering the circulation, possibly affecting their extracellular effects. Indeed, upon precipitation of nucleosomes from sera of septic baboons and patients with meningococcal sepsis, we noticed that histone H3 was clipped, giving rise to an N-terminally truncated fragment of ∼13-kDa. Furthermore, in a mouse sepsis model, a similarly sized histone H3 fragment was found in the circulation, although its origin remained unclear.49 This truncated form of histone H3 is reminiscent of the band observed upon incubation of purified nucleosomes with active FSAP and was not observed upon incubation with FSAP-deficient serum. However, we cannot exclude that other proteases may also be involved in histone H3 proteolysis,52 because intracellular proteases, including cathepsin L, are known to cleave H3 to a similarly sized band.53-55 In addition, histone H3 is cleaved by glutamate dehydrogenase at the same position, also cleaving after K27.56,57 Nonetheless, we did not observe an effect of H3 truncation on the cytotoxicity of nucleosomes.

Importantly, free histones were not detectable in sera obtained from septic baboons and patients with meningococcal sepsis. We speculate that histones freed from nucleosomes by the DNases in blood induce the activation of FSAP. Indeed, FSAP-AP complexes were present in these samples, indicating that FSAP activation had occurred. The proteolysis of free histones may serve as a mechanism to protect against the harmful effects of free histones. Future studies of experimental sepsis in an FSAP-deficient animal model are required to rule out the possible contribution of proteases other than FSAP to histone proteolysis in vivo. Although histone H3 was not degraded in FSAP-deficient serum, some histone neutralization occurred in the absence of FSAP, possibly as a result of histone neutralization by inter-α inhibitor protein or albumin.20,21 In addition to FSAP, APC has been described to proteolyze histones.11 In contrast to APC, FSAP becomes activated upon contact with dead cells and histones, supporting a role for FSAP in histone proteolysis in the absence of thrombin formation.

Nevertheless, proteolysis of histones by FSAP seems efficient. FSAP binds to histones with high affinity (apparent Kd, 42 nM),34 and we showed that 100 µg/mL of histones (∼7 µM) was degraded by FSAP in 50% serum (∼90 nM) within 2 minutes. Hence, the molar ratio of histone to FSAP was 78:1; thus, each FSAP molecule may cleave multiple histone molecules before it is inactivated by serpins or other inhibitors, although further kinetic analysis is required. We previously observed a transient rise of FSAP-AP and FSAP–C1 inhibitor complexes in surgical patients in the days after transhiatal esophagectomy, which paralleled the level of nucleosomes. In addition, the levels of FSAP-AP and FSAP–C1 inhibitor complexes in patients admitted with meningococcal sepsis continued to increased at 12 and 24 hours after admission.35 Given that serpin-protease complexes have a short half-life of 20 to 47 minutes, these data suggest that an exhaustion of FSAP activity through complex formation with serpins is not likely to occur, at least not during the time window that samples were obtained for the present study described herein.57-59

In conclusion, our results signify that the form in which histones circulate during disease crucially determines their extracellular effects and highlight the need for specific assays to detect free histones and nucleosomes. Both histone binding to DNA and the proteolysis of histones by FSAP confer specific protection against the cytotoxic effects of free histones. Furthermore, the newly revealed role of FSAP in the protection against histone-induced cytotoxicity may be of therapeutic potential.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank T. van der Poll for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Landsteiner Foundation for Blood Transfusion Research (LSBR 1616 and 0817). Research in the F.L. laboratory was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM097747 and R01GM116184) and NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (5U19AI062629 and R21AI113020).

Authorship

Contribution: G.M., H.v.R., and I.B. performed biochemical studies; G.M. and H.v.R. performed cytotoxicity experiments; J.H. and F.L. were responsible for obtaining meningococcal patient samples and baboon sepsis samples, respectively; G.M., B.M.L., and S.Z. developed the concept; B.M.L. and S.Z. supervised the study; G.M., B.M.L., and S.Z. wrote the manuscript; and all authors had the opportunity to discuss results and comment on the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.Z. received an unrestricted grant from Viropharma. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sacha Zeerleder, Department of Immunopathology, Sanquin Research, Plesmanlaan 125 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: s.s.zeerleder@amc.uva.nl.

References

Author notes

B.M.L. and S.Z. contributed equally to this study.